Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Thursday, 12 February 2026, 5:04 PM

Non-Communicable Diseases, Emergency Care and Mental Health Module: 19. Disability and Community Rehabilitation

Study Session 19 Disability and Community Rehabilitation

Introduction

In recent years, more and more health professionals have started to distinguish impairment from disability. Impairment refers to the physical, intellectual, mental and/or sensory characteristics or conditions that limit a person’s individual or social functioning, in comparison with someone without these impairments.

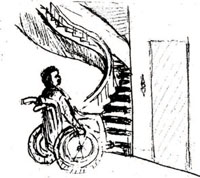

Disability, in contrast, is not something individuals ‘have’, but has a wider social meaning. It is the exclusion of people with impairments due to attitudinal and environmental barriers that limits their full and equal participation in the life of the community and society at large (Figure 19.1). It is now accepted that the disabling environmental and social barriers are major causes of the disability experienced by individuals with impairments.

It is important to ensure the inclusion of disabled people in society. Inclusion refers to the need to make sure that people with disabilities have access to all necessary services and that the barriers and limitations they experience in society are reduced. In this study session you will learn about disability and impairment, and ways to support the inclusion and rehabilitation of people with impairments in your community.

Learning Outcomes for Study Session 19

When you have studied this session, you should be able to:

19.1 Define and use correctly all of the key words printed in bold. (SAQs 19.1 and 19.4)

19.2 Differentiate between impairment and disability, and briefly summarise the different ‘models’ of disability. (SAQ 19.1)

19.3 Describe key aspects of appropriate communication with people with disabilities. (SAQ 19.2)

19.4 Describe the prevalence of disability and the major causes of disability. (SAQ19.3)

19.5 Explain how inclusion can be promoted using the twin-track approach. (SAQ 19.4)

19.6 Explain how you can support community rehabilitation in your catchment area. (SAQ 19.4)

19.1 Models of disability

A good way of understanding the distinction between impairment and disability is to consider some of the ways that disability has been thought of in the past. In this part of the session you are going to look at several models of disability. As you do this, think about what each model ‘says’ about the person with an impairment. This will help you to understand – and respond to – traditional beliefs about disability.

A ‘model’ in this context means a particular way of understanding or describing a complex social phenomenon such as disability.

19.1.1 The charity model

The charity model of disability is a traditional way of viewing persons with disabilities as being dependent and helpless. In this model, people with disabilities are seen as:

- Objects of charity

- Having nothing to give, only to receive

- Being inherently poor, needy and fully dependent on charity or welfare for their survival.

Persons with disabilities is generally considered to be the term most consistent with the language used by the United Nations (UN).

The charity model is often related to traditional cultural and religious beliefs and practices such as the giving of alms. The problem with such practices is that they reinforce the idea that people with disabilities are helpless recipients of ‘charity’ from a ‘caring’ society, rather than subjects with rights.

Can you think of people in your community who see disability in terms of the charity model? How would you try to change their views?

Some of the people in your community who offer alms to people with disabilities (in the form of money, clothes, food, etc.) may think about disability in terms of the charity model. You can discuss this with them sensitively, asking if they have considered that other forms of assistance, such as supporting people with disabilities in demanding better social provision might be more effective in the longer term.

19.1.2 The medical model

The medical model of disability focuses primarily on the medical problems of persons with disabilities and emphasises medical solutions. It assumes that:

- The problem of disability is due entirely to the individual’s condition or impairment.

- People with disabilities are — first and foremost — ‘patients’.

- The problem of disability requires a purely medical solution.

In the medical model the problem of disability is addressed by medical experts through providing treatment for people with disabilities, rather than asking them what they want. Like the charity model, this approach is largely unconcerned with the social or environmental features of disability.

19.1.3 The social model

The social model of disability views people with disabilities as being disabled less by their impairment than by society’s inadequate response to their specific needs. The social model emphasises that:

- Disability is best thought of as a social problem.

- The problem is not the person with disabilities or their impairment, but the unequal and discriminatory way they are treated by society.

- The solution lies in removing the barriers that restrict the inclusion and participation of people with disabilities in the social life of the community.

The emphasis on the removal of barriers focuses attention on a range of issues ignored in both the charity and medical models. For instance, it challenges inequalities before the law, restrictions caused by physical structures (the way buildings and villages are designed), and discrimination – the disabling aspects of negative attitudes towards people with disabilities.

19.1.4 The human rights model

The human rights model of disability can be seen as the most recent development of the social model. It states that:

- All human beings are equal and have rights that should be respected without distinction of any kind.

- People with disabilities are citizens and, as such, have the same rights as those without impairments.

- All actions to support people with disabilities should be ‘rights based’; for example, the demand for equal access to services and opportunities as a human right.

Like the social model, the human rights model places responsibility for addressing the problems of disability on society rather than on the person with disabilities. It also places a responsibility on you to ensure that appropriate legislation designed by the government is complied with at a local level.

19.2 Types of impairments

There are many types of impairments, the most common types will be briefly discussed in this section.

19.2.1 Mobility and physical impairments

There are a variety of physical impairments that impact on functioning and mobility. These include limitations in the use of the limbs, limited manual dexterity, limited coordination of limbs, cerebral palsy, spinal bifida and sclerosis. Physical impairment can be congenital (something one is born with), or it can be the result of disease, accident, violence or old age.

19.2.2 Sensory impairments

Visual impairments

Virtually everyone will experience a visual impairment at some point in their lives. Usually these are minor or treatable, e.g. temporary visual impairments caused by bright lights or headaches, or age-related visual impairment that can be ‘self-treated’ with reading spectacles. But they can also be serious, e.g. permanent visual impairment or more severe conditions requiring medical treatment. Visual impairment can be congenital (present at birth), due to genetic conditions, or the result of accidents, violence, or diseases such as trachoma, glaucoma and cataracts (you learned about this in Study Session 5).

Hearing impairments

There is a wide variety in the form and severity of hearing impairments, ranging from partial to complete deafness. People who are partially deaf can often use hearing aids to assist their hearing (Figure 19.2).

Deafness can be genetic, be evident at birth, or occur later in life as a result of disease or due to old age. Both deaf and partially deaf people use sign language as a means of communication. The lack of knowledge of sign language amongst the general population can create communication difficulties for deaf and partially deaf people and can also be thought of as a disabling barrier.

19.2.3 Intellectual impairments

Intellectual impairments are characterised by significant limitations in intellectual functioning, which also impact on many everyday social and practical skills. The medical term for these impairments is ‘intellectual disability’ (see Study Session 17, which also discusses some common causes).

19.2.4 Multiple impairments

Some people have to cope with several impairments, either permanently or for periods of time (e.g. during an illness). Examples of permanent multiple impairments include people who are both deaf and blind, and people with both a physical and intellectual impairment.

Take a little time now to think about the ways in which people with either intellectual or multiple impairments might be further disadvantaged by the social environment in which they live. In wealthy countries (such as the USA and in Europe), or in big cities, the impact of these impairments may be lessened by the use of (expensive) technology. However, access to such technology is often very limited in the villages and rural areas of developing countries. This highlights the fact that, while people may have the same experiences in terms of impairment, their experience of disability might be very different.

19.3 Appropriate and acceptable language

There is often much confusion around the language to be used when talking about disability and/or addressing persons with disabilities. Acceptable terminology changes over time and may be different in different countries.

19.3.1 Appropriate and inappropriate terms

In your daily work it is important to keep the following guidelines in mind:

- When describing a person, focus on their abilities and actions rather than their limitations, and avoids words that imply that they are passive ‘objects’ rather than active subjects. Expressions like ‘she uses a wheelchair’ or ‘he is partially sighted’ are preferred to terms such as ‘confined to a wheelchair’ or ‘partially blind’.

- Avoid ‘sensationalising’ an impairment by using expressions such as ‘afflicted with’, ‘victim of’, ‘suffering from’, and so on (see also Table 19.1).

- Emphasise the individual, rather than the impairment, by saying, for example, ‘a person with paraplegia’, instead of ‘a paraplegic’ or ‘a paraplegic person’. For the same reason, avoid grouping individuals into generic categories through expressions like the deaf, the blind, etc.

- When talking about places or buildings designed to overcome the barriers faced by people with disabilities, use the term ‘accessible’ (e.g. ‘an accessible parking space’) rather than ‘parking for the disabled’ or ‘for the handicapped’.

- Finally, people without disabilities should not be referred to as ‘normal’, ‘healthy’ or ‘able-bodied’. People with disabilities are not – as such expressions suggest – ‘abnormal’, ‘sick’ or ‘unable’.

It is appropriate for you to continue using words such as ‘see’, ‘look’, ‘walk’, ‘listen’, when talking to people with various disabilities, even if the person is, for example, partially sighted or uses a wheelchair or hearing aid.

| Inappropriate use | Appropriate use |

|---|---|

The disabled, the handicapped | People with disabilities |

Cripple, physically handicapped or wheelchair bound. | A person with a physical disability/impairment or wheelchair user |

Spastic | A person with cerebral palsy |

Deaf and dumb | A person with hearing and speech impairments |

The blind | People who are blind, or partially sighted, or visually impaired people |

The deaf | People who are deaf, or hearing-impaired people |

19.3.2 Communication with people who have impairments

When introduced to a person with a disability, it is appropriate to offer to shake hands. People with limited hand use or who wear an artificial limb can usually shake hands. (Shaking hands with the left hand is an acceptable greeting.)

When you are talking with a person who has difficulty speaking, listen attentively. Be patient and wait for the person to finish, rather than correcting or speaking for them. If necessary, ask short questions that require only short answers, or a nod or shake of the head. Never pretend to understand if you are having difficulty doing so. Instead, repeat what you have understood and allow the person to respond.

When speaking with a person who uses a wheelchair or a person who uses crutches, place yourself at eye level in front of the person to facilitate the conversation. When speaking with someone with a visual impairment, make sure to introduce yourself by name. When conversing in a group, remember to identify the person to whom you are speaking.

To get the attention of a person with a hearing impairment, tap the person on the shoulder or wave your hand. Look directly at the person and speak clearly, slowly, and expressively to determine if the person can read your lips. Not all people with a hearing impairment can read lips. For those who do, be sensitive to their needs by facing the light source and keep hands, food and drink away from your mouth when speaking.

People with an intellectual disability may have difficulty understanding language that is complex, or contains difficult words. It is therefore important when talking with someone with an intellectual disability to follow the guidelines in Box 19.1.

Box 19.1 Guidelines for talking with a person with an intellectual disability

- Speak slowly and leave pauses for the person to process your words.

- Speak directly to the person, and ensure they feel central to the consultation.

- Speak in clear short sentences. Don’t use long, complex, or technical words and jargon.

- Ask one question at a time, provide adequate time for the person to formulate and give their reply.

- If necessary obtain information from parents/caregivers, maintain the focus on the person with the disability through your eye contact, body language and/or touch.

19.4 Myths and facts about disability

In the community, many people do not know much about disability and have a misunderstanding of what it is like to live with a disability. Some common myths about disability are given below in Box 19.2, together with the actual facts so that you can help to challenge these myths.

Box 19.2 Common myths about disability

Myth 1: People with disabilities are brave and courageous.

- Fact: Adjusting to impairment requires adapting to particular circumstances and lifestyle, not bravery and courage.

Myth 2: Wheelchair use is confining; people who use wheelchairs are ‘wheelchair-bound’.

- Fact: A wheelchair, like a bicycle or an automobile, is a personal mobility assistive device that enables someone to move around.

Myth 3: All persons with hearing disabilities can read lips.

- Fact: Lip-reading skills vary among people and are never entirely reliable.

Myth 4: People who are blind acquire a ‘sixth sense’.

- Fact: Although most people who are blind develop their remaining senses more fully, they do not have a ‘sixth sense’.

Myth 5: Most people with disabilities cannot have sexual relationships.

- Fact: Anyone can have a sexual relationship by adapting the sexual activity. People with disabilities can have children naturally or through adoption. People with disabilities, like other people, are sexual beings.

As a healthworker, you can help remove barriers by encouraging participation of people with disabilities in your community through:

- using accessible sites for meetings and events

- advocating for a barrier-free environment

- speaking up when negative words or phrases are used about persons with disabilities

- accepting persons with disabilities as individuals with the same needs, feelings and rights as yourself.

19.5 Situation of disability in Ethiopia

According to available survey results from the 2006 census, of a total population in Ethiopia of more than 73 million, there are 805,535 (or 0.8 million) persons with disabilities. However, relevant government authorities, researchers, and people active in the field of disability all agree that the figures are very low compared to the prevalence of disability in neighboring countries and other developing countries. The number of persons with disabilities in Ethiopia is likely to be underestimated due to inadequate definitions or what constitutes disability and which disabilities should be included in the count. It is also likely that parents are not willing to disclose that they have a child or family member with a disability because of stigma. The actual number of people with disabilities in Ethiopia is therefore likely to be much higher.

Box 19.3 lists some of the major preventable causes of disabling impairments. Poverty is not only a cause, but also a major consequence of disability in Ethiopia. It is estimated that 95% of all persons with disabilities in the country are living in poverty. Many of these people live in rural areas, where basic services are limited and often inaccessible to persons with disabilities and their families. As a result, most persons with disabilities do not have access to services and lack the opportunities to earn a level of income to facilitate independent living. In the remainder of this study session, you will consider what you can do to tackle this problem.

Box 19.3 Major causes of impairment

- Disease

- Poverty

- Wars

- Drought

- Famine

- Harmful traditional practices

- Household, work place and traffic accidents.

19.6 The twin- track approach

To promote and facilitate equal opportunities for people with disabilities and their full participation in society, the twin track approach focuses on their inclusion in both a) mainstream and b) disability-specific development initiatives. Neither track (mainstream or disability specific) is better or more important than the other. They are both required to ensure that the needs of all people with disabilities are met.

19.6.1 Mainstream programmes and services

The first track focuses on mainstream programmes and services, which are not specifically designed for persons with disabilities, such as public health services, mainstream schools, community development programmes, transportation, etc. This track focuses on making these mainstream services more accessible for people with disabilities. The approach in mainstream schools, for instance, might involve the construction of ramps to make classrooms accessible to wheelchair users. Similarly, textbooks and other written materials might be transcribed into Braille copy for students with visual impairments.

What efforts might you make to promote and facilitate the inclusion of persons with disabilities in mainstream programmes and services? One of the things you can do, for example, is to make sure that the meetings you arrange in your community (e.g. your awareness-raising meetings, see Study Session 18) are equally accessible to everyone (Figure 19.3). This way you set a good example that can be followed by influential people in your community.

19.6.2 Disability-specific programmes and services

The second track focuses on disability-specific programmes and services designed on purpose to address the needs of people with disabilities, such as orthopaedic centres, special schools, etc. You should find out about any such projects that may be operating in your area. You could help in making these disability-specific programmes and services more accessible at community level. For example, you might direct the families of children with motor or sensory impairments to a project that provides physical aids such as crutches (Figure 19.4), hearing aids, braces or wheelchairs (Figure 19.5).

19.7 Community-based rehabilitation (CBR)

Community health centres are often the first point of contact for persons with disabilities and their families seeking healthcare. In addition, in some regions, Community-Based Rehabilitation (CBR) programmes provide home-based support to parents and children with disabilities as well as to older people with disabilities. Currently, these CBR programmes are primarily run by the non-governmental organisations (NGOs) that belong to the CBR Network in Ethiopia (CBRNE).

Non-governmental organisations (or NGOs) are non-profit-making organisations that are not part of the government. Examples of NGOs active in Ethiopia include UNICEF and AMREF.

You can support CBR activities by finding out about impairments among children in your locality, focusing on the early identification of impairments, and providing basic interventions to children, youth and adults with impairments. As noted in Section 19.6.2, you can also facilitate links between individuals with impairments and specialised services.

19.8 UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities

The UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (UNCRPD) aims to protect the rights and dignity of persons with disabilities. Parties to the Convention (including Ethiopia) are required to promote, protect, and ensure the full enjoyment of human rights by persons with disabilities. The Convention was signed in 2007 and ratified by the Ethiopian House of Peoples’ Representatives in June 2010.

The UNCRPD introduced the concept of ‘reasonable accommodation’. This acknowledges that people with disabilities face many barriers and reasonable accommodation should be made to redress this. Reasonable accommodation involves providing the necessary and appropriate modification and adjustments, while ‘not imposing a disproportionate or undue burden’. This reflects the fact that addressing all the barriers faced by people with disabilities requires a lot of resources that may not always be available. Nevertheless, there are a number of possible reasonable accommodations that providers could make. These include making existing facilities (such as health centres) accessible for people using crutches and wheelchairs, providing sign language interpretation, providing information in Braille, and so on. At a community level, you can help in making these changes.

Summary of Study Session 19

In Study Session 19, you have learned that:

- Impairments and disability are different. The first relates to the physical aspects of disablement whilst the second relates to the social aspects of disability.

- The four broad categories of impairment are: physical, sensorial, intellectual and multiple.

- Different ways of thinking about disability can be seen in the four main ‘models’ of disability: the charity model, the medical model, the social model and the human rights model.

- Myths (misconceptions) about people with disabilities and the use of inappropriate terminology when discussing disability is commonplace.

- Poverty can cause disability, but can also be a consequence of disability, as many people with a disability in Ethiopia do not have a job.

- The aims of the UN Convention on disability are being pursued in Ethiopia through the use of the twin-track approach and the notion of ‘reasonable accommodation’. You should consider using these to play your part in facilitating the inclusion of people with disabilities in mainstream society.

Self-Assessment Questions (SAQs) for Study Session 19

Now that you have completed this study session, you can assess how well you have achieved its Learning Outcomes by answering these questions. Write your answers in your Study Diary and discuss them with your Tutor at the next Study Support Meeting. You can check your answers with the Notes on the Self-Assessment Questions at the end of this module.

Read the following case study and answer the questions at the end.

Case Study 19.1 Mr Abebe

When Mr Abebe was 5 years old, he was hit by a truck when it passed through his village while he was playing on the road. He was severely injured and as a consequence of the accident his left leg had to be amputated. It took a long time for the young boy to recover, but he gradually learned to walk again with the help of crutches. He became so skilful in using his crutches that, by the time he reached adolescence, he would often take part in the village football game, by leaning on one crutch while kicking the ball. Mr Abebe is now a grown-up man with a small vegetable farm. On Wednesdays he sells some of his products at the local market. Unfortunately Mr Abebe’s vision has recently started to deteriorate due to an untreated eye infection. His vision is now so bad that he has difficulty reading. Recently the organisation that manages the local market provided some training documents on food hygiene. Unfortunately Mr Abebe was not able to read these documents, as they were printed in a very small print.

SAQ 19.1 (tests Learning Outcome 19.1 and 19.2)

- a.In the case study, identify what type(s) of impairment Mr Abebe has, and how his impairment leads to disability.

- b.Give an example of inclusion from Mr Abebe’s case story.

Answer

- a.Mr Abebe has multiple impairments: he has a physical impairment that impacts on his mobility (because of a leg amputation). Mr Abebe also has impaired vision. Because of his visual impairments, Mr Abebe could not read the training documents on food hygiene provided by the organisation that manages the market. Because the document was only available in small print, Mr Abebe did not have access to this information, leading to a disabling situation.

- b.When Mr Abebe was an adolescent, he was so skilful with his crutches that he could participate in the local football game. This is an example of inclusion.

SAQ 19.2 (tests Learning Outcome 19.3)

Read the descriptions of the following three situations of communication with a person with a disability. For each situation indicate whether the communication is appropriate or not. If it is not appropriate, explain why.

A When you speak to someone who uses a wheelchair, sit down so that both your heads are approximately at the same level.

B When someone has difficulty speaking, interrupt them and try to finish their sentence for them so that they have to speak less.

C When you speak to someone who has an intellectual disability, you should ask all your questions at once so that you are finished quickly.

Answer

A This type of communication is appropriate. When you speak to someone in a wheelchair, it is good to place yourself at eye level to facilitate the conversation.

B This communication style is inappropriate. When someone has difficulty speaking it is important to be patient and wait for the person to finish their sentences, rather than to interrupt them or speak for them.

C This communication style is inappropriate. When you speak to someone with an intellectual disability, you should try to speak slowly and in clear and short sentences. Ask one question at a time and give the person enough time to respond.

SAQ 19.3 (tests Learning Outcome 19.4)

From the list below, identify which factors are likely or unlikely causes of impairment that could result in disability. If it is an unlikely cause, explain why.

A A genetic condition a person is born with.

B Malnutrition because the crops failed a few years in a row.

C Being possessed by the devil.

Answer

A This is a likely cause of disability. Genetic conditions can give rise to a range of disabilities, including intellectual disability and physical impairments.

B This is a likely cause of disability. Malnutrition makes people more susceptible to disease, which may in turn lead to impairments. Malnutrition can also directly cause impairment. For example, if a mother receives inadequate nutrition during pregnancy, it can lead to intellectual impairment in the child.

C This is not a cause of disability. Use the social or human rights model to explain disability, rather than a local cultural view (like being possessed by the devil).

SAQ 19.4 (tests Learning Outcomes 19.1, 19.5 and 19.6)

Give one example of how you can improve inclusion for people with disabilities in mainstream programmes and services, and one example of how you can improve access to services designed specifically for people with disabilities.

Answer

Examples of how you can improve access for people with disabilities in your community to mainstream programmes and services include:

- Setting the right example by making sure that your awareness-raising meetings are accessible for everyone.

- Liaising with the local school (or other local facilities) so that ramps are provided to make sure that children who use crutches or a wheelchair can access the school.

Examples of how you can improve access to specialist services for people with disabilities include:

- Finding out about initiatives especially designed for people with disabilities (e.g. providers of hearing aids, crutches, etc.) in your local area, and making sure that the people concerned in your community know about them.

- Looking out for people with impairments in your area, so that underlying causes due to disease or injury can be treated, and so that the people concerned can be referred to specialist services where these exist.