Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Tuesday, 3 March 2026, 5:14 AM

Nutrition Module: 5. Nutritional Assessment

Study Session 5 Nutritional Assessment

Introduction

In Study Session 4 you learned about infant and young child feeding that will promote optimal growth and the most favourable development of infants and young children. In this study session you will learn about different methods of assessing the nutritional status of children and adults. Biochemical, biophysical and dietary methods of assessing nutritional status are briefly introduced. You will also learn more about the anthropometric and clinical methods of assessing nutritional status as they are more applicable to your practice.

Learning Outcomes for Study Session 5

When you have studied this session, you should be able to:

5.1 Define and use correctly all of the key terms printed in bold. (SAQs 5.1 and 5.2)

5.2 Describe anthropometric measurements used for community level screening of malnutrition. (SAQs 5.2 and 5.3)

5.3 Identify anthropometric indicators of the nutritional status for children, adults and pregnant women. (SAQs 5.3, 5.4 and 5.5)

5.4 Identify children and adults with malnutrition by comparing their measurements to cut-off values. (SAQ 5.4)

5.5 Assess micronutrient deficiencies using clinical signs and symptoms. (SAQ 5.6)

5.1 Nutritional assessment

As a Health Extension Practitioner you will frequently be dealing with your community’s nutritional problems. Using different nutritional assessment (see Box 5.1) methods discussed in this section you will learn how to assess the nutritional status of children, mothers and other adults living in your community.

Box 5.1 Definition of nutritional assessment

Nutritional assessment is the interpretation of anthropometric, biochemical (laboratory), clinical and dietary data to determine whether a person or groups of people are well nourished or malnourished (over-nourished or under-nourished).

Nutritional assessment can be done using the ABCD methods. These refer to the following:

- A.Anthropometry

- B.Biochemical/biophysical methods

- C.Clinical methods

- D.Dietary methods.

The word anthropometry comes from two words: Anthropo means ‘human’ and metry means ‘measurement’. In your community you will be able to use anthropometric measurements to assess either growth or change in the body composition of the people you are responsible for. The different measurements taken to assess growth and body composition are presented below.

5.2 Anthropometric measurements used to assess growth

To assess growth in children you can use several different measurements including length, height, weight and head circumference.

5.2.1 Length

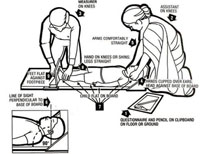

A wooden measuring board (also called sliding board) is used for measuring the length of children under two years old to the nearest millimetre (as shown in Figure 5.1). Measuring the child lying down always gives readings greater than the child’s actual height by 1-2 cm.

Procedure

To measure the length of a child under two years, you need one assistant and a sliding board.

As you can see in Figure 5.1, you need an assistant to help you measure a child using this method.

- Both assistant and measurer are on their knees (arrows 2 and 3).

- The assistant holds the child’s head with both hands and makes sure that the head touches the base of the board (arrow 4).

- The assistant’s arms should be comfortably straight (arrow 5).

- The line of sight of the child should be perpendicular to the base of the board (looking straight upwards) (arrow 6).

- The child should lie flat on the board (arrow 7).

- The measurer should place their hands on the child’s knees or shins (arrow 8).

- The child’s foot should be flat against the footpiece (arrow 9).

- Read the length from the tape attached to the board.

- Record the measurement on the questionnaire (arrow 1).

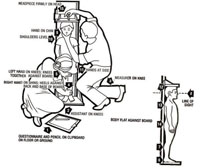

5.2.2 Height

This is measured with the child or adult in a standing position (usually children who are two years old or more). The head should be in the Frankfurt position (a position where the line passing from the external ear hole to the lower eye lid is parallel to the floor) during measurement, and the shoulders, buttocks and the heels should touch the vertical stand. Either a stadiometer or a portable anthropometer can be used for measuring. Measurements are recorded to the nearest millimetre.

Procedure

As with measuring a child’s length, to measure a child’s height, you need to have another person helping you. Figure 5.2 illustrates the procedures, and in Figure 5.3 you can see a young child having his height measured.

- Both the assistant and measurer should be on their knees (arrows 2 and 3).

- The right hand of the assistant should be on the shins of the child against the base of the board (arrow 4).

- The left hand of the assistant should be on the knees of the child to keep them close to the board (arrow 5).

- The heel, the calf, buttocks, shoulder and occipital prominence (prominent area on the back of the head) should be flat against the board (arrows 6, 7, 14, 13 and 12).

- The child should be looking straight ahead (arrow 8).

- The hands of the child should be by their side (arrow 11).

- The measurer’s left hand should be on the child’s chin (arrow 9).

- The child’s shoulders should be levelled (arrow 10).

- The head piece should be placed firmly on the child’s head (arrow 15).

- The measurement should be recorded on the questionnaire (arrow 1).

5.2.3 Weight

A weighing sling (spring balance), also called the ‘Salter Scale’ is used for measuring the weight of children under two years old, to the nearest 0.1 kg. In adults and children over two years a beam balance is used and the measurement is also to the nearest 0.1 kg. In both cases a digital electronic scale can be used if you have one available. Do not forget to re-adjust the scale to zero before each weighing. You also need to check whether your scale is measuring correctly by weighing an object of known weight.

Procedures

In Figure 5.3 you can see the procedures for weighing a child under two years old using a Salter Scale. The photo in Figure 5.4 shows a small boy being weighted using the scale.

- Adjust the pointer of the scale to zero level.

- Take off the child’s heavy clothes and shoes.

- Hold the child’s legs through the leg holes (arrow 1).

- Hold the child’s feet (arrow 2).

- Hang the child on the Salter Scale (arrow 3).

- Read the scale at eye level to the nearest 0.1 kg (arrow 5).

- Remove the child slowly and safely.

Sometimes you will have to improvise. For example in the field set up, it is difficult to measure very young children who cannot sit by themselves using the weighing pant attached to the scale. In addition, some children panic during the measurement and urinate, making the pant dirty. Therefore, mothers or caregivers may not be happy to let their children be measured in such a manner. The weighing scale with the pant can be improvised by using a plastic washing-basin which is attached to the Salter Scale and adjusting the reading to zero. You need to ensure the basin is as close to the ground as possible in case the child falls out, and to make the child feel secure during weighing. If the basin is dirty, then you need to clean it with a disinfectant. This is a much more comfortable and reassuring weighing method for the child and you can use it for ill children much more easily than the approaches described above.

How do you know whether your weight measuring scale is correct?

You can check the accuracy of the scale you’re using by measuring an object of known weight.

5.2.4 Head circumference

The head circumference (HC) is the measurement of the head along the supra orbital ridge (forehead) anteriorly and occipital prominence (the prominent area on the back part of the head) posteriorly. It is measured to the nearest millimetre using flexible, non-stretchable measuring tape around 0.6cm wide. HC is useful in assessing chronic nutritional problems in children under two years old as the brain grows faster during the first two years of life. But after two years the growth of the brain is more sluggish and HC is not useful. In Ethiopia, HC is measured at birth for all newborn babies.

Now you have looked at how to take different measurements you are going to learn how the measurements are converted into different indices.

5.3 Converting measurements to indices

An index is a combination of two measurements or one measurement plus the person’s age. The following are a few indices that you may find useful in your work:

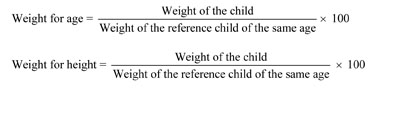

Weight-for-age is an index used in growth monitoring for assessing children who may be underweight. You assess weight-for-age of all children under two years old when you carry out your community-based nutrition (CBN) activities every month.

Height-for age is an index used for assessing stunting (chronic malnutrition in children). Stunted children have poor physical and intellectual performance and lower work output leading to lower productivity at individual level and poor socioeconomic development at the community level. Stunting of children in a given population indicates the fact that the children have suffered from chronic malnutrition so much so that it has affected their linear growth.

Stunting is defined as a low height for age of the child compared to the standard child of the same age. Stunted children have decreased mental and physical productivity capacity.

Weight-for-height is an index used for assessing wasting (acute malnutrition).

Wasting is defined as a low weight for the height of the child compared to the standard child of the same height. Wasted children are vulnerable to infection and stand a greater chance of dying.

Body mass index is the weight of a child or adult in kg divided by their height in metres squared: Weight (kg)/(Height in metres)2

Here is how to calculate each index for children in your community.

Birth weight is weight of the child at birth and is classified as follows:

| more than 2500 grams | = | normal birth weight |

| 1500–2499 grams | = | low birth weight |

| less than 1500 grams | = | very low birth weight |

How does stunting affect socioeconomic development?

You have read that there are a number of ways that stunted children are at a disadvantage, even into their adult lives. They have poor physical and intellectual performance and are more likely to have a lower work output. This means that not only are they less productive at individual level, there are also poor socioeconomic outcomes at the population level.

5.3.1 What is an indicator?

An indicator is an index (for example, a scale showing weight for age, or weight for height) combined with specific cut-off values that help you determine whether a child is underweight or malnourished; for example, a child whose weight for age, or weight for height, falls below the cut-off values shown in Table 5.1 is considered to be underweight or malnourished.

You will be able to use anthropometric indicators to assess nutritional status, to evaluate the effects of interventions, to admit children to an intervention (treatment) programme and to discharge them from a programme. These indicators are therefore very important and knowing how to use them will help you plan effective nutrition interventions. Table 5.1 summarises how indicators of underweight, wasting and malnutrition are derived from the weight and height of children relative to their age, with the cut-off values (column 2) for each indicator (column 1) based on the standard deviation (SD) of the child’s measurement from the norm for a child of that age.

The growth chart in each Health Post and on the child health card will help you assess whether a child is underweight.

What are the indicators for diagnosing severe acute malnutrition?

Indicators for SAM are a child with standard deviation less than 3 and/or bilateral pitting oedema. If one of these signs is detected, the child is suffering from SAM.

5.4 Anthropometric measurements used to assess body composition

In assessing body composition (fat content) the body is considered to be made up of two compartments: the fat mass and the fat free mass. Therefore different measurements are used to assess these two compartments.

5.4.1 Measurements of fat-mass (fatness)

As you read earlier Body Mass Index (BMI) is the weight of a person in kilograms divided by their height in metres squared. A non-pregnant adult is considered to have a normal BMI when it falls between 18.5 and 25 kg/m2. Table 5.2 shows you the different categories of nutritional status based on a person’s BMI.

| BMI(Kg/m2) cut-offs | Nutritional status |

|---|---|

| more than 40.0 | Very obese |

| 30.0-40.0 | Obese |

| 25-29.9 | Overweight |

| 18.5-24.9 | Normal |

| 17-18.49 | Mild chronic energy deficiency |

| 16-16.9 | Moderate chronic energy deficiency |

| less than 16.0 | Severe chronic energy deficiency |

If an adult person has a BMI of less than 16 kg/m2 they will not be able to do much physical work because they will have very poor energy stores. In addition they will be at increased risk of infection due to impaired immunity.

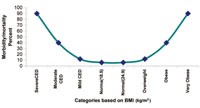

Risk of mortality and morbidity is related to the nutritional status as assessed by the BMI. If people are too fat or too thin their health suffers. The risk of mortality and morbidity increases with a decrease in the BMI. Similarly, when the BMI increases to over 25 kg/m2, the risk of mortality and morbidity increases. The relationship between BMI and risk of morbidity and mortality is shown in Figure 5.6.

What are the problem associated with having high (greater than 25kg/m2) or low (less than 18.5 kg/m2) BMI?

The risk of mortality and morbidity increases with a decrease in the body mass index. Similarly, when the body mass index increases over 25 kg/m2, the risk of mortality and morbidity as well as other diseases such as hypertension, diabetes mellitus and cancer also increases.

5.4.2 Measuring fat-free mass (muscle mass)

An accurate way to measure fat-free mass is to measure the Mid Upper Arm Circumference (MUAC). The MUAC is the circumference of the upper arm at the midway between the shoulder tip and the elbow tip on the left arm. The mid-arm point is determined by measuring the distance from the shoulder tip to the elbow and dividing it by two. A low reading indicates a loss of muscle mass.

MUAC is a good screening tool in determining the risk of mortality among children, and people living with HIV/AIDS. MUAC is the only anthropometric measure for assessing nutritional status among pregnant women. It is also very simple for use in screening a large number of people, especially during community level screening for community-based nutrition interventions or during emergency situations.

MUAC is therefore used as a screening tool for community based nutrition programmes such as an outpatient therapeutic programme (OTP), for community-based interventions, supplementary feeding programmes and enhanced outreach programmes throughout Ethiopia. MUAC is also used for screening target children and pregnant women for severe acute malnutrition (SAM) and moderate acute malnutrition (MAM).

5.4.3 Measuring the MUAC of children

A special tape is used for measuring the MUAC of a child (see Figure 5.7). The tape has three colours, with the red indicating severe acute malnutrition, the yellow indicating moderate acute malnutrition and the green indicating normal nutritional status. Figure 5.8 shows you how to use the tape to measure a child’s MUAC.

Procedures for measuring MUAC

- Ask the mother to remove any clothing that may cover the child’s left arm. If possible, the child should stand erect and sideways to the measurer.

- Estimate the midpoint of the left upper arm (arrow 6).

- Straighten the child’s arm and wrap the tape around the arm at the midpoint. Make sure the numbers are right side up. Make sure the tape is flat around the skin (arrow 7).

- Inspect the tension of the tape on the child’s arm. Make sure the tape has the proper tension (arrow 7) and is not too tight or too loose (arrows 8 and 9). Repeat any step as necessary.

- When the tape is in the correct position on the arm with correct tension, read the measurement to the nearest 0.1 cm (arrow 10).

- Immediately record the measurement.

You can see the MUAC of a young child being measured in Figure 5.9.

Table 5.3 sets out the cut-off values using the MUAC measurement and how these relate to the level of malnutrition in children and adults.

| Target Groups | MUAC (in cm) | Malnutrition |

|---|---|---|

| Children under five | 11-11.9 | Moderate acute malnutrition (MAM) |

| <11 cm | Severe acute malnutrition (SAM) | |

| Pregnant women/adults | 17-21 cm | Moderate malnutrition |

| 18-21 cm with recent weight loss | Moderate malnutrition | |

| <17 cm | Severe malnutrition | |

| <18 cm with recent weight loss | Severe malnutrition |

Why is MUAC a useful measurement tool?

There are a number of reasons. For pregnant women it is the only anthropometric measure that can give an accurate reading of their malnutrition status. Also, because MUAC can be measured quickly and easily, it is also used when screening large numbers of children and adults.

5.5 Clinical methods of assessing nutritional status

As a frontline health worker providing health services at community level, you will almost certainly encounter many people with nutritional deficiency problems. In addition to the anthropometric assessments, you can also assess clinical signs and symptoms that might indicate potential specific nutrient deficiency.

Clinical methods of assessing nutritional status involve checking signs of deficiency at specific places on the body or asking the patient whether they have any symptoms that might suggest nutrient deficiency from the patient. Clinical signs of nutrient deficiency include: pallor (on the palm of the hand or the conjunctiva of the eye), Bitot’s spots on the eyes, pitting oedema, goitre and severe visible wasting (these signs are explained below).

5.5.1 Checking for bilateral pitting oedema in a child

In order to determine the presence of oedema, you should apply normal thumb pressure on both feet for three seconds (count the numbers 101, 102, 103 in order to estimate three seconds without using a watch). If a shallow print persists on both feet, then the child has nutritional oedema (pitting oedema). You must test for oedema with finger pressure (see Figure 5.10) because you cannot tell by just looking.

Grades of oedema

Depending on the presence of oedema on the different levels of the body it is graded as follows. An increase in grades indicates an increase in the severity of oedema.

0 = no oedema

+ = Below the ankle (pitting pedal oedema)

++ = Pitting oedema below the knee

+++ = Generalised oedema.

5.5.2 Bitot’s spots

These are a sign of vitamin A deficiency. Look at Figure 5.11; as you can see, these spots are a creamy colour and appear on the white of the eye.

5.5.3 Goitre

Goitre is a swelling on the neck and is the only visible sign of iodine deficiency (Figure 5.12).

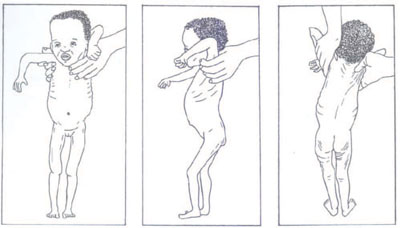

5.5.4 Visible severe wasting

In order to determine the presence of visible severe wasting for children younger than six months, you will need to ask the mother to remove all of the child’s clothing so you can look at the arms, thighs and buttocks for loss of muscle bulk. Sagging skin and buttocks indicates visible severe wasting (as you can see in Figure 5.13).

Table 5.4 summarises the main symptoms of nutritional problems and the deficiencies they signal.

| Sign/symptom | Nutritional abnormality |

|---|---|

Pale: palms, conjunctiva, tongue Gets tired easily; loss of appetite shortness of breath | Anaemia: may be due to the deficiency of iron, folic, vitamin B12, acid, copper, protein or vitamin B6 |

| Bitot’s spots (whitish patchy triangular lesions on the side of the eye) | Vitamin A deficiency |

| Goitre (swelling on the front of the neck) | Iodine deficiency disorder |

Aster is a one-year-old girl who was brought to your health post by her mother, with a complaint of body swelling and poor appetite for one month.

Upon anthropometric assessment her weight-for-height was less than 3 SD and on examination, she has bilateral pitting oedema. What is the nutritional problem Aster is suffering from and what are the indicators?

Aster’s weight-for-height index is an indicator of severe underweight and this, combined with the bilateral pitting oedema, tells you that she has severe acute malnutrition.

5.6 Dietary methods of assessing nutritional status

Dietary methods of assessment include looking at past or current intakes of nutrients from food by individuals or a group to determine their nutritional status. You can ask what the family or the mother and the child have eaten over the past 24 hours and use this data to calculate the dietary diversity score.

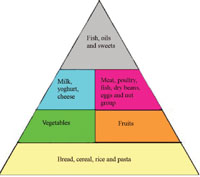

Dietary diversity is a measure of the number of food groups consumed over a reference period, usually 24 hours. Generally, there are six food groups that our body needs to have everyday. These can be represented in the food guide pyramid which you read about in Study Session 2 and which is reproduced in Figure 5.14.

You may recall from Study Session 2 the base or widest part of the pyramid indicates the need for higher quantities of consumption of carbohydrate source foods, while the tip is narrow, indicating the need for eating only small amounts of fats and sweet things. If a person consumes any examples of the food type from each of the six groups in 24 hours, we can say that their dietary diversity score is six. Dietary diversity score is an indicator of both the balance of nutrient consumption and the level of food security (or insecurity) in the household. The higher the dietary diversity score in a family, the more diversified and balanced the diet is and the more food-secure the household.

As part of the dietary assessment you should also check the salt iodine level of households using the single solution kit (SSK). This enables you to determine whether the salt iodine level is 0, more than 15 parts per million (PPM) or less than 15 PPM. You can see a photo of an SSK in Figure 5.15. Normally, an iodized salt should have iodine level of more than 15 PPM to be effective in preventing iodine deficiency and its consequences. As a Level IV Health Extension Practitioner you are expected to test the iodine level of household salts twice a year.

You can use the various methods of assessing nutritional status discussed in this study session to evaluate the nutrition status of people living in your community. Whichever measurements you are taking you should remember that it is important to follow procedures correctly and take accurate measurements that ensure the quality of data generated about the individuals you are responsible for in your community.

Summary of Study Session 5

In Study Session 5 you have learned that:

- Nutritional assessment is the interpretation of data to determine whether a person or groups of people are well nourished or malnourished (over nourished or under-nourished).

- Anthropometry is the measurement of physical dimensions such as height or weight, as well as the fat mass composition of the human body to provide information about a person’s nutritional status.

- An index is a combination of two anthropometric measurements or an anthropometric measurement plus age. An indicator is a combination of an index and a cut-off point.

- There are procedures for measuring length, height, weight and MUAC.

- Weight-for-age is an index used to assess child growth.

- MUAC is used for community-based screening of children who are less than five years old and for pregnant women. Knowing the MUAC can help when assessing severe acute malnutrition and moderate acute malnutrition.

- Body mass index is the best measure of non-pregnant adult nutritional status.

- Bilateral oedema and the different grades of oedema are checked on the top of the foot and around the ankle using both hands and pressing each foot for three seconds. Its presence indicates severe acute malnutrition.

- Clinical signs and symptoms, such as goitre or Bitot’s spots, are also important indicators of micronutrient deficiencies.

- Checking for the iodine level of salt in households is done by using a single solution kit, and should be done twice yearly.

Self-Assessment Questions (SAQs) For Study Session 5

Now that you have completed the study session, you can assess how well you have achieved its Learning Outcomes by answering these questions. Write your answers in your Study Diary and discuss them with your Tutor at the next Study Support Meeting. You can check your answers with the Notes on the Self-Assessment Questions at the end of the Module.

SAQ 5.1 (tests Learning Outcome 5.1)

What is nutritional assessment used for? Name the different ways in which it can be carried out.

Answer

Nutritional assessment is used to determine whether a person or group of people is well nourished or malnourished (over-nourished or under-nourished). It involves the interpretation of anthropometric, biochemical (laboratory), clinical and/or dietary data.

SAQ 5.2 (tests Learning Outcomes 5.1 and 5.2)

What is the difference between an anthropometric index and an indicator?

Answer

An anthropometric index is a combination of two measurements (or a measurement and an age). An indicator is an index combined with cut-off values.

SAQ 5.3 (tests Learning Outcomes 5.2 and 5.3)

What kinds of things can be measured to make a nutritional assessment?

Answer

In order to make a nutritional assessment, you can measure height, weight, body mass or mid-upper arm circumference.

SAQ 5.4 (tests Learning Outcomes 5.3 and 5.4)

Describe some of the different methods you could use to determine whether a child is suffering from severe acute malnutrition.

Answer

In order to determine whether a child is suffering from acute malnutrition you can assess the following:

- the weight of the child compared with reference child of the same height

- whether the child is suffering from bilateral pitting oedema

- the child’s MUAC

- whether there are signs of severe wasting.

SAQ 5.5 (tests Learning Outcome 5.3)

What are the anthropometric indicators of moderate acute malnutrition in:

- Children

- Pregnant women

Answer

Indicators of moderate malnutrition in:

- Children: MUAC = 11–11.9cm

- Pregnant women: MUAC = 17 to 21cm OR 18 to 21cm with recent weight loss.

SAQ 5.6 (tests Learning Outcome 5.5)

What nutrient deficiency do the following clinical signs/symptoms indicate?

- a.Pallor

- b.Goitre

- c.Bitot’s spots

- d.Bilateral pitting oedema

- e.Severe visible wasting

Answer

The following list shows the clinical signs/symptoms and the nutritional problems they indicate:

- a.Pallor = anaemia

- b.Goiter = iodine deficiency disorder

- c.Bitot’s spots = vitamin A deficiency

- d.Bilateral pitting oedema = severe acute malnutrition

- e.Severe visible wasting = acute malnutrition