Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Sunday, 8 March 2026, 10:29 AM

Nutrition: 6. Common Nutritional Problems in Ethiopia

Study Session 6 Common Nutritional Problems in Ethiopia

Introduction

In this study session you are going to learn about common nutritional problems that are of public health importance in Ethiopia. In Study Session 5 you learned how to assess the nutritional status of children and adults. You are now going to look at how to use the knowledge and skills you learnt in that study session to identify children and adults with nutritional problems.

You will also learn about acute and chronic malnutrition in the community and something about their causes. The knowledge acquired will enable you to identify children with malnutrition in your community at the earliest possible stage and to consider strategies you can use to manage the situation effectively.

Learning Outcomes for Study Session 6

When you have studied this session, you should be able to:

6.1 Define and use correctly all of the key words printed in bold. (SAQs 6.1 and 6.2)

6.2 Summarise the magnitude and types of nutritional problems in Ethiopia. (SAQ 6.1)

6.3 List the common causes of malnutrition in children using a conceptual framework. (SAQ 6.2)

6.4 Describe the consequences of malnutrition to the community. (SAQ 6.4)

6.5 List the strategies to promote proper nutrition in the community. (SAQ 6.3s and 6.4)

6.1 Types of malnutrition

Malnutrition is a general term that includes many conditions, including undernutrition, overnutrition and micronutrient deficiency diseases (like vitamin A deficiency, iron deficiency anaemia, iodine deficiency disorders and scurvy).

Wasting, or thinness, is an indicator of acute (short-term) malnutrition. Wasting is usually the result of recent food insecurity, infection or acute illness such as diarrhoea. Measurement of wasting or thinness is often used to assess the severity of an emergency situation, with severe wasting being highly linked with the death of a child. Figure 6.1 shows a child with undernutrition.

Stunting, or shortness, is an indicator of chronic (long-term) malnutrition. It’s often associated with poor development during childhood and is one of the harmful effects of poverty. Stunting is commonly used as an indicator for development, as it is highly related with poverty.

Underweight is an indicator of both acute and chronic malnutrition. Underweight is a highly useful indicator when examining nutritional trends. It is the indicator used to monitor the Millennium Development Goal (MDG) of ending hunger, and targets of halving the prevalence of underweight children and adults by 2015.

Which type of malnutrition is a result of recent food insecurity or illness?

Wasting (thinness) is the result of recent food insecurity or illness such as diarrhoea or infection.

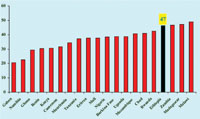

Look at Figure 6.2 carefully. You can see that Ethiopia has a high rate of stunting (chronic malnutrition). Forty seven percent of children under five years of age are considered to be stunted and this is the fourth highest percentage in Africa.

6.2 Common forms of malnutrition in Ethiopia

Malnutrition is a major public health problem in many developing countries. It is one of the main health problems facing women and children in Ethiopia. The country has the second highest rate of malnutrition in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA). Ethiopia faces the four major forms of malnutrition: acute and chronic malnutrition, iron deficiency anaemia (IDA), vitamin A deficiency (VAD), and iodine deficiency disorder (IDD). The 2005 Demographic Health Survey (DHS) has shown that about 47 % and 11% of Ethiopian children under five years of age were stunted and wasted respectively. Thirty eight percent of children under five years of age were underweight and 11% were severely underweight.

Malnutrition is also very high amongst women. One in four women (27%) in Ethiopia are thin i.e. they have body mass index of less than 18.5 (Ethiopian Demographic Health Survey of 2005).

What are the major forms of malnutrition that are common in Ethiopia?

The common forms of malnutrition in Ethiopia include acute and chronic malnutrition, iron deficiency anemia (IDA), vitamin A deficiency (VAD), and iodine deficiency disorder (IDD).

According to the DHS, the prevalence of low birth weight (LBW) in Ethiopia is one of the highest in the world, and has been estimated to be 14%. Based on mother’s subjective assessment of the size of the baby at birth, 21% of births were reported to be very small and 7% were reported as smaller than average. One major contributing factor for LBW is the poor nutritional status of women both before and during pregnancy, made worse by inadequate weight gain during pregnancy (DHS).

6.3 Classification of malnutrition

You need to know how to identify acute malnutrition, and to differentiate between severe acute malnutrition and moderate acute malnutrition.

In the past, severe acute malnutrition was classified in the way described in Box 6.1 and Figures 6.3 and 6.4 overleaf. You need to know this, because you may come across people who still use these terms.

Box 6.1 Previous classifications of severe acute malnutrition

Protein-energy-malnutrition (PEM): A clinical syndrome present in infants and children as a result of deficient intake and/or utilisation of food.

Marasmus: Severe form of acute malnutrition that is characterised by wasting of body tissues. Marasmic children are extremely thin. (Figure 6.3)

Kwashiorkor: Severe form of acute malnutrition characterised by bilateral oedema and weight-for-height of greater or equal to -2 SD (Figure 6.4)

Marasmic-Kwashiorkor: Severe form of acute malnutrition characterised by bilateral oedema and weight-for-height of less than -2 SD.

However there is now a new way of classifying malnutrition so you need to know and should use these terms. With the current classification, all the three forms of severe protein energy malnutrition are now classified as severe acute malnutrition.

6.4 Causes of malnutrition

This section looks at possible causes of malnutrition and asks you to consider in particular the level of malnutrition in your community.

The causes of malnutrition can be very complex. Malnutrition is influenced by many factors acting at multiple levels. These factors often act in a continuous cycle and include dietary intake issues, diseases, food insecurity, inadequate maternal and child health care and sanitation services. Illiteracy and poverty may also influence the food intake of people in your community and become causes of malnutrition.

Activity 6.1 Identifying causes of malnutrition in your community

Select a few neighbours or other people from your community and discuss with them what they think may be the possible causes of any malnutrition that can be found in your area (see Figure 6.4). Document your discussions and possible causes in your Study Diary and discuss your findings with your Tutor.

Now you will learn more about the causes of malnutrition using a way of looking at the problem that will help you identify its various underlying reasons.

Because the causes of malnutrition are complex, they should be addressed in a systematic way in order to find the right solutions for the problem. Usually malnutrition is not the single consequence of a single factor but a mixture of different causes. The size of the contribution of each of these may vary.

Look carefully at Figure 6.5. You will see that the causes of malnutrition have been divided into three main headings: the basic causes; the underlying causes; and the immediate causes.

You are now going to look at each of these causes in more detail.

6.4.1 Immediate causes of malnutrition

The immediate causes associated with malnutrition include poor diet and disease.

Poor diet: If a child doesn’t get an adequate diet they will become malnourished. The poor diet might be due to not enough food, or a lack of variety of foods in meals; low concentrations of energy and nutrients in meals; infrequent meals; insufficient breastmilk; and early weaning.

Disease: Diseases, especially infectious diseases, cause undernutrition because a sick child may not eat or absorb enough nutrients, or may lose nutrients from the body due to vomiting or diarrhoea, or have increased nutrient needs which are not met.

The diseases most likely to cause undernutrition are: measles; diarrhoea; AIDS; respiratory infections; malaria; and intestinal worms.

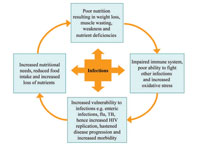

Look at Figure 6.6 (the malnutrition-infection cycle). This shows the relationship between infection and undernutrition. As you can see from the figure, infection will lead to undernutrition and the undernutrition also leads to infection.

6.4.2 Underlying causes of malnutrition

Poor diet and disease are the immediate causes of malnutrition for children but it is always important to try to find out why that child has a poor diet or why they have developed the disease. The underlying causes differ within different communities and from family to family but it is useful to group them into: family food shortages; inadequate care of children and women; unhealthy environment and poor health services; and too many children in a family to feed.

For each underlying cause you identify, there is probably another, ‘deeper’ cause. For example, a child may have a poor diet because the family has little food. But why is the family short of food? Perhaps they have too little land or a low income. But why have they too little land? Keep probing and asking ‘But why?’ Eventually you should be able to determine the basic causes.

Let us now further examine the underlying causes under three of the main groups given above.

Family food shortages: Many families do not have enough food to feed everyone properly throughout the year. But why are these families short of food?

The possible reasons for family food shortages may be that there is a large number of families in the locality, leading to over-cultivation of their lands. Another might be the effects of low income or poor budgeting. Some people may spend so much on ‘non-essential’ things such as ‘khat’, cigarettes and beer, so there is not enough money left for the family’s food needs. There may also be poor distribution of food among families.

Activity 6.2 Identifying local causes of family food shortages

Think of a family in your community who has food shortages and discuss with a work colleague what the reasons for the food shortages could be. Make a note of these in your Study Diary and discuss your findings with your Tutor.

There will be different causes for food shortages, some depending on the region in which you live. You might have identified large family size, small size of farming land, low income, or extravagance by the husbands on unnecessary items, such as cigarettes and beer.

Inadequate care of children and women: Nutrition and health care are often determined by the amount of care given to women and children, and this is strongly affected by a woman’s workload, access to resources and her education.

If the mother is busy, she might not have enough time to breastfeed and care for her child. Many women are uneducated and have little knowledge about feeding, childcare and hygiene. Thus they lack awareness of the correct things to do. These same women often cannot or do not attend clinics or women’s groups where they could learn skills to improve their lives and that of their families.

Activity 6.3 Effects of women’s activity on nutritional status of children

Discuss with some of your colleagues how the mothers in your community spend their time. Discuss how their activities affect the nutritional status of their children. Write down your discussion points in your Study Diary and discuss these with your Tutor.

Mothers may spend much of their time fetching water, farming or doing labour work; a minority of mothers may be government employees. If a mother is busy with these and other activities, she may not get time to breastfeed, prepare foods for her children and or ensure her children’s hygiene. Children of these mothers may be at higher risk of undernutrition either due to lack of appropriate and adequate feeding, or due to repeated infections as a result of poor sanitary conditions.

Unhealthy environment and poor health services: Disease is more likely to occur, especially among young children, when there are poor living conditions such as overcrowding, low immunization coverage and poor health services.

6.5 Basic causes of malnutrition

The availability and control of resources (human, economic and organisational) at the various levels of society are a result of four major factors.

These are political factors, cultural factors, environmental factors, and social factors. Any one or a combination of these can be a basic cause of malnutrition.

6.5.1 Political factors

Certain political factors, such as policy decisions and economic situations caused by inflation or war, can cause undernutrition. A good example was the high level of malnutrition amongst many Ethiopian citizens during the Ethio-Eritrean war.

6.5.2 Cultural factors

Can you think of health beliefs that might contribute to nutritional problems in your own community? There may be many and it can be hard to get people to realise that these beliefs have a negative impact on their or their children’s bodies.

For example, abrupt weaning due to pregnancy, the belief that food should not be given to a child who is suffering from measles or diarrhoea, and sharing food from the same bowl between different children, can result in the child getting less than their body requirements, are examples of some of the cultural factors that may affect nutrition.

6.5.3 Environmental or natural disasters

Drought, floods and earthquakes are other basic causes that can lead to malnutrition. The 1977 drought of Ethiopia is a good example of a natural disaster with terrible consequences.

6.5.4 Social factors

Poverty is the reason that some families cannot produce or buy more food. Men often leave home to search for work, leaving women to bring up children alone. Poverty can lead to family quarrels and child abuse. Often women have less access to money, land and other resources, and less control over family decisions than men.

You have now studied the causes of undernutrition and thought about how these might be found in your own community. The next section will give you the opportunity to look at some of the common consequences of malnutrition on a community.

6.6 Consequences of malnutrition for communities

The enormous consequences of malnutrition are often not appreciated because they may be hidden. Often there are no obvious signs, and the victims themselves are silent and not aware of the problem. Yet, data available (DHS 2005) now indicates that, in Ethiopia, malnutrition starts very early in life for large numbers of children who become progressively more malnourished during the first two years of life. By 24 months, considerable damage to the developing child has been done and satisfactory recovery becomes less likely.

Well-nourished women are likely to be fit and healthy and able to look after their family well. The outcomes of pregnancy and lactation are improved when the woman is healthy herself. As you read in an earlier study session in this Module, the nutritional needs of a pregnant and a lactating woman are greater than at other times in her life. During pregnancy, the food the mother eats also helps to meet the nutritional needs of the unborn baby. During lactation, the food the mother eats helps in production of breastmilk.

Just as malnutrition has many causes, its effects are also multidimensional in nature.

6.6.1 Increased risk of disease and death

Malnutrition, sub-optimal infant feeding practices, and vitamin A deficiency, significantly lower the resistance to infections and dramatically increase the risk of illnesses and death. Millions of children die of severe acute malnutrition each year.

6.6.2 Low productivity of the malnourished individuals

Stunting has a serious impact on the productivity of individuals. Stunted children grow up to become less productive adults. Studies show that labour productivity declines as severity of stunting increases. Iodine deficiency also significantly reduces the productivity of an individual.

6.6.3 Poor school performance and attendance

Proper nutrition is essential for mental and physical development and for school performance. Malnutrition reduces children’s learning ability, school performance and attendance.

Iodine deficiency lowers the ability of children to think and become creative and productive adults. Iodine is necessary for the normal development of the brain of the fetus during pregnancy.

6.6.4 Poverty perpetuation (a vicious circle)

Malnutrition affects children, women, and communities and will prevent them from reaching their full mental and physical capacity. As we have discussed earlier, a malnourished child will grow to a malnourished adult. The productivity of the adult will be decreased and poverty will continue.

6.6.5 Intergenerational cycle of malnutrition

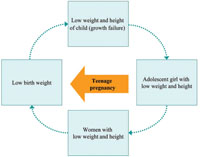

As you read earlier, malnutrition has an intergenerational cycle. A malnourished mother will give birth to a low birth weight baby; the low birth weight baby will grow as a malnourished child, then to a malnourished teenager, then to a malnourished pregnant woman, and so the cycle continues. This is illustrated in Figure 6.7.

6.7 Strategies to promote proper nutrition in a community

You have now had an opportunity to consider some of the problems of malnutrition, its common causes, and the consequences of malnutrition at family level and community level. As a Health Extension Practitioner you may be able to decrease the rate of malnutrition and minimise the effects of malnutrition on your own community.

There are six strategies that have been found to promote proper nutrition in a community. These are:

- Basic education

- Healthy environment

- Maternal and child care

- Healthy social and family life

- Proper agriculture

- Public health measures.

As a Health Extension Practitioner you have a role to play in all of these strategies.

Basic education: This is a very important for improving child nutrition and care. Therefore advocacy should be done to promote equal chances of education for both boys and girls since this is important to enable them to become better parents themselves.

Healthy environment: Availability and easy access to safe and adequate water for drinking, cooking and cleaning are important aspects of each person’s development and the maintenance of their health.

Maternal and childcare: Prevention of prematurity, proper antenatal care and promotion of good feeding practices are important interventions that may help to decrease malnutrition within your community.

Healthy social and family life: Strong family planning services may help families to limit the number of children they have; social integration and communal care may support orphans and children with special needs.

Proper agriculture: Diversification through planting the right number of different kinds of seeds should be promoted, and food distribution at household level should be equitable, giving children and pregnant mothers priority.

Public health measures: These include prevention and treatment of maternal infections during pregnancy and delivery. Immunizations against preventable diseases as well as an emphasis on growth promotion and monitoring activities are also important public health strategies to prevent malnutrition in the community.

Part of your role includes working with other professionals and community leaders to help promote these strategies and help improve the nutritional status of people living in your community.

Summary of Study Session 6

In Study Session 6 you have learned that:

- Malnutrition includes a wide range of clinical disorders resulting from an unbalanced intake of energy, protein or other nutrients. It can present as under or overnutrition. Malnutrition is one of the main health problems facing women and children in Ethiopia.

- Ethiopia faces the four major forms of malnutrition: acute and chronic malnutrition, iron deficiency anaemia (IDA), vitamin A deficiency (VAD), and iodine deficiency disorder (IDD).

- Inadequate food intake, diseases like measles, food insecurity and limited access to foodstuffs, plus poor sanitation and inadequate health services, and inadequate maternal and childcare practices are the commonest causes of malnutrition.

- The consequences of malnutrition include an increased risk of diseases and death, poor productivity of the malnourished individuals as well as poor academic performance and loss of attendance of children from school. Other consequences are poverty perpetuation (a vicious circle) and an intergenerational cycle of malnutrition.

- The strategies to prevent malnutrition include advocating for equal access to education for both boys and girls, and creating a healthy environment. The provision of proper antenatal care, safe delivery and postnatal care services are also important. Encouraging the use of family planning methods, prevention and treatment of infections of pregnant mothers, and babies and immunization of children and pregnant women are among other useful strategies for addressing malnutrition.

Self-Assessment Questions (SAQs) for Study Session 6

Now that you have completed this study session, you can assess how well you have achieved its Learning Outcomes by answering these questions. Write your answers in your Study Diary and discuss them with your Tutor at the next Study Support Meeting. You can check your answers with the Notes on the Self-Assessment Questions at the end of this Module.

First read Case Study 6.1.

Case Study 6.1 Chaltu’s story

Chaltu is two years old. She was brought to you because she has had diarrhoea for the last two weeks. You took anthropometric measurements; her weight is 7 kg, her height is 80 cm, and her MUAC is 10.5 cm. You found pitting oedema of both legs.

When you asked Chaltu’s mother about the family situation, the mother told you that Chaltu is the seventh child in the family. The family owns only one hectare of land and the land is not fertile.

SAQ 6.1 (tests Learning Outcomes 6.1 and 6.2)

What is the nutritional status of Chaltu? Is Chaltu malnourished? Explain how you have come to your answer.

Answer

You have to use the growth chart to decide the nutritional status of Chaltu.

- Her weight for age is below the third centile

- Her weight for height is < 70%

- Her height for age is below the third centile

- Her MUAC is 10.5cm and has bilateral pitting oedema.

Chaltu has severe acute malnutrition (because her weight for height is < 70%, her MUAC < 11cm, and she has bilateral pitting leg oedema). Any one of these three signs is enough to classify Chaltu as having severe acute malnutrition (SAM).

Chaltu is also stunted (because the height for age is below the third centile) and she is also underweight (because her weight for age is below the third centile).

SAQ 6.2 (tests Learning Outcomes 6.1 and 6.3)

What do you think are the immediate, underlying and basic causes of Chaltu’s malnutrition?

Answer

The immediate cause of Chaltu’s malnutrition may be the diarrhoea that she had for the last two weeks.

The underlying cause may be either family food shortage (because many family members have to live off a very small piece of land that is not very fertile), poor childcare by the mother because she has many children to care for or a combination of these factors.

The basic cause in this case may be poverty, which is the common basic cause in many of malnourished families.

SAQ 6.3 (tests Learning Outcome 6.5)

List the strategies you will use for Chaltu’s family in order to promote proper nutrition in this family.

Answer

As a Health Extension Practitioner you may be able to advise Chaltu’s family on proper feeding practices, strong family planning services, dietary diversity, proper care and treatment of her current illnesses, and on the need for education of children (both girls and boys).

SAQ 6.4 (tests Learning Outcomes 6.4 and 6.5)

What is the impact of malnutrition on communities? How can you help prevent some of the negative effects of malnutrition?

Answer

Malnutrition is a major public health problem in Ethiopia and has a significant impact on communities, in particular for women and children. Millions of children die of severe acute malnutrition each year and poor nutrition prevents many children and adults from ever reaching their full mental and physical capacity. For example, children who are malnourished are at risk of stunting, which affects their productivity when they are older; malnutrition also affects their learning ability, school performance and attendance. All of these consequences have a social and economic impact on the community and the country.

As a Health Extension Practitioner you can help to minimise the effects of malnutrition in your community. In particular, through good maternal and child health care, you can help promote good feeding practices in families and emphasise the importance of clean water for drinking, cooking and cleaning. You can also support strong family planning services to help families space or limit the number of children they have. Other examples where you will have a role include advocating for basic education for girls as well as boys, encouraging communities to grow a wide range of nutritious foods and to ensure particularly that children and pregnant mothers have the right amount of food they need to be healthy.