Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Monday, 16 February 2026, 2:32 AM

Antenatal Care Module: 10. Estimating Gestational Age from Fundal Height Measurement

Study Session 10 Estimating Gestational Age from Fundal Height Measurement

Introduction

In this study session, you will learn how to carry out an important measurement that should be done at every antenatal visit — measuring the height of the top of the mother’s uterus as a way of assessing whether her baby is growing normally. We teach you two ways of doing this — using your fingers, and using a soft measuring tape. This will enable you to estimate the stage of pregnancy she has reached, and check the accuracy of the due date calculated from the mother’s last normal menstrual period. Then we discuss possible reasons for the uterus growing too quickly or too slowly, and what actions you should take if you suspect that something may be wrong.

Learning Outcomes for Study Session 10

When you have studied this session, you should be able to:

10.1 Define and use correctly all of the key words printed in bold. (SAQ 10.1)

10.2 Know how to measure fundal height using the finger method and a soft measuring tape. (SAQ 10.1)

10.3 Interpret fundal height measurements to assess normal fetal growth in relation to gestational age. (SAQ 10.2)

10.4 Identify possible causes of abnormal fundal height measurements and take the appropriate actions. (SAQ 10.3)

10.1 What does measuring the height of the mother’s uterus tell us?

The purpose of measuring the height of the mother’s uterus is to determine if the baby is growing normally at each stage of the pregnancy. When you measure the uterus, you check to see where the top of the uterus is.

Healthy signs

- The height of the uterus matches the gestational age of the fetus, i.e. the number of weeks or months of pregnancy (gestation).

- The top of the uterus rises in the mother’s abdomen by about two finger-widths, or 4 cm every month.

Warning signs

- The height of the uterus does not match the number of weeks or months of pregnancy.

- The top of the uterus rises more than, or less than, two finger-widths or 4 cm every month.

Do you remember what the domed region at the top of the uterus is called? (You learned this in Study Session 3.)

It is called the fundus.

When you measure how high the top of the uterus has reached in the mother’s abdomen, you are measuring the fundal height. This is a much more accurate way of estimating fetal growth than weighing the mother. Measuring the fundal height will show you three things:

- How many months the woman is pregnant now.

- The probable due date. If you were able to figure out the due date from the mother’s last monthly bleeding, measuring the height of the top of the uterus can help you see if this due date is probably correct. If you were unable to figure out her due date from her last normal menstrual period (LNMP), measuring the fundal height can help you figure out a probable due date. This should be done during the first antenatal check-up.

- How fast the baby is growing. At each antenatal check-up, measure the fundal height to see if the baby is growing at a normal rate. If it is growing very fast or very slowly, there may be a problem.

As the baby grows inside the uterus, you can feel the uterus grow bigger in the mother’s abdomen. The top of the uterus moves about two finger-widths or 4 cm higher each month (Box 10.1).

Box 10.1 Changes in fundal height in a normal pregnancy

At about three months (13-14 weeks), the top of the uterus is usually just above the mother’s pubic bone (where her pubic hair begins).

At about five months (20-22 weeks), the top of the uterus is usually right at the mother’s bellybutton (umbilicus or navel).

At about eight to nine months (36-40 weeks), the top of the uterus is almost up to the bottom of the mother’s ribs.

Babies may drop lower in the weeks just before birth. You can look back at Figure 7.1 in Study Session 7 to see a diagram of fundal height at various weeks of gestation.

10.2 How to measure the fundal height

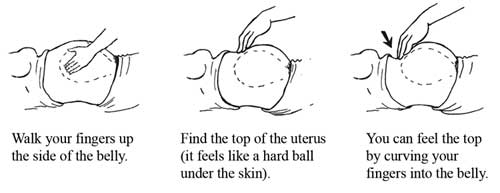

To feel the uterus, have the mother lie on her back with some support under her head and knees. Explain to her what you are going to do (and why) before you begin touching her abdomen. Your touch should be firm but gentle. Walk your fingers up the side of her abdomen (Figure 10.1) until you feel the top of her abdomen under the skin. It will feel like a hard ball. You can feel the top by curving your fingers gently into the abdomen.

10.2.1 How to measure fundal height using the finger method

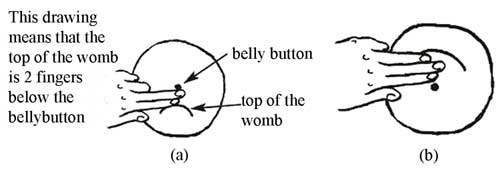

If the top of the uterus is below the bellybutton, measure how many fingers below the bellybutton it is. If the top of the uterus is above the bellybutton, measure how many fingers above the bellybutton it is.

Look carefully at Figure 10.2. If the baby is growing normally, by how many finger-widths should the uterus rise in the second trimester (3-6 months of pregnancy, or 15-27 completed weeks of gestation)?

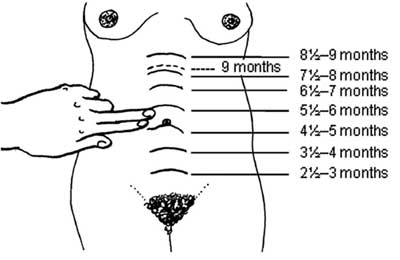

Figure 10.3 Fundal height at 7 months’ gestation.

Figure 10.3 Fundal height at 7 months’ gestation.Fundal height should increase by 6 finger-widths (two finger-widths every month) in the second trimester.

How many fingers above the bellybutton should the top of the uterus be at 7 months’ gestation?

See Figure 10.3 for the answer.

How do you explain the position of the dotted line at 9 months in Figure 10.2, which is below the line showing fundal height at 8½ to 9 months?

Babies may drop lower in the weeks just before birth (look back at Box 10.1).

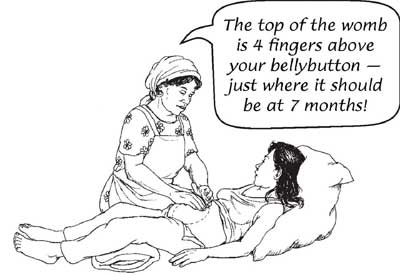

Look at the diagrams in Figure 10.4 (a) and (b). How many weeks pregnant is the woman in each case, based on the finger method of measuring fundal height shown in Figure 10.2?

In Figure 10.4(a) the woman is about 4½ months pregnant. In Figure 10.4 (b) she is about 6½ months pregnant (three fingers above the bellybutton).

When you measure fundal height at every antenatal visit, write down the number of fingers you used to measure the height of the uterus on the woman’s antenatal record card. Put a ‘+’ (plus) sign in front of the number if the top of the uterus is above the bellybutton. Put a ‘–’ (minus) sign in front of the number if the top of the uterus is below the bellybutton.

How would you record the measurements shown in Figure 10.4(a) and (b)?

The measurement in Figure 10.4(a) would be recorded as -2. The measurement in Figure 10.4(b) would be +3.

Limitations of the finger method

You need to be aware that the finger method for estimating gestational age (the number of weeks/months of pregnancy) has some limitations that affect its accuracy.

Look at your own hands. Can you suggest why the finger method might give a different estimate of gestational age if two different health workers used this method to measure the same woman’s fundal height?

Because of the big variation in the thickness of our fingers, there could be up to three weeks difference between the fundal height measurement of the same woman made by two different people. (This is known as ‘inter-observer variation’, i.e. variation between different observers.)

Even if the same health worker measures the fundal height of the same woman several times on the same day, the answer may be different each time, because the finger method is not very precise. (This is known as ‘intra-observer variation’, i.e. variation by a single observer at different times.)

Finally, you might have realised that the distance between the symphysis pubis (pubic bone) and the umbilicus (bellybutton) varies between women when they are not pregnant, and this variation affects the accuracy of the fundal height measurement using the finger method. For example, it assumes that the distance between the pubic symphysis and the umbilicus is 20 cm at 20 weeks’ gestation, but it can be as long as 30 cm and as short as 14 cm.

To overcome these limitations, it is recommended that you measure fundal height using a soft tape measure if you have one, as described next.

10.2.2 How to measure fundal height using a soft tape measure

You can use this method when the top of the uterus grows as high as the woman’s bellybutton.

During the second half of pregnancy, the size of the uterus in centimetres is close to the number of weeks that the woman has been pregnant. For example, if it has been 24 weeks since her last normal menstrual period, the uterus will usually measure 22-26 cm. The uterus should grow about 1 cm every week, or 4 cm every month.

- Lay a cloth or soft plastic measuring tape on the mother’s abdomen, holding the 0 (zero) on the tape at the top of the pubic bone (see the arrow in Figure 10.5a).

- Follow the curve of her abdomen, and hold the tape at the top of her uterus (Figure 10.5b).

- Write down the number of centimetres (cm) from the top of the pubic bone to the top of the uterus.

Doctors, nurses and many midwives are taught to count pregnancy by weeks instead of months. They start counting at the first day of the last normal menstrual period (LNMP), even though the woman probably got pregnant two weeks later. Counting this way makes most pregnancies 40 weeks long (or you can say a normal gestation is 40 weeks).

10.3 What if the size of the uterus is not what you expected?

If you are measuring correctly and you do not find the top of the uterus where you expect it to be, based on the date the woman gave you for her LNMP, it could mean three different things:

- The due date you got by counting from the LNMP could be wrong.

- The uterus (and the baby) could be growing too fast.

- The uterus (and the baby) could be growing too slowly.

10.3.1 The due date you got by counting from the LNMP is wrong

There are several reasons why a due date figured from the LNMP could be wrong. Sometimes women do not remember the date of their LNMP correctly. Sometimes a woman misses her menstruation for another reason, and then gets pregnant later. This woman could really be less pregnant than you thought, so the uterus is smaller than you expect. Or sometimes a woman has a little bleeding after she gets pregnant. If she assumed that was her LNMP, this woman will be one or two months more pregnant than you thought. The uterus will be bigger than you expect.

Remember due dates are not exact. Women often give birth up to 2 or 3 weeks before or after their due date. This is usually safe.

If the due date does not match the size of the uterus at the first visit, make a note. Wait and measure the uterus again in two to four weeks. If the uterus grows about two finger-widths or 1 cm a month, the due date that you got from feeling the top of the uterus is probably correct. The due date you got by counting from the LNMP was probably wrong.

10.3.2 The uterus is growing too quickly

If the uterus grows more than 2 finger-widths a month, or more than 1 cm a week, several different causes are possible:

- The mother may have twins.

- The mother may have diabetes.

- The mother may have too much water (amniotic fluid) in the uterus.

- The mother may have a molar pregnancy (a tumour instead of a baby).

![]() If you think there might be twins, even if you can find only one heartbeat, refer the woman to the nearest health centre.

If you think there might be twins, even if you can find only one heartbeat, refer the woman to the nearest health centre.

The mother may have twins

It can be very difficult to know for sure that a mother is pregnant with twins. Signs of twins are that:

- The uterus grows faster or larger than normal.

- You can feel two heads or two bottoms when you feel the mother’s abdomen.

- You can hear two heartbeats. This is not easy to detect, but it may be possible in the last few months.

We will show you how to listen to the fetal heartbeat through the mother’s abdomen in Study Session 11. For now, we are focusing on twins as a possible reason for the uterus being larger than expected. Here are two ways to try to hear the heartbeats of twins:

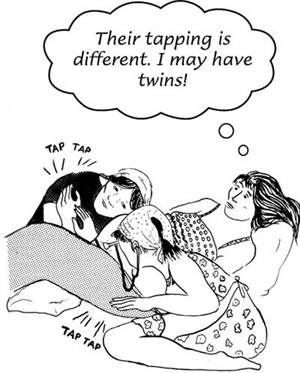

- Find the heartbeat of one baby. Ask a helper to listen for other places where the heartbeat is easy to hear. If she hears a heartbeat, ask her to listen to one place while you listen to the other. Each of you can tap the rhythm of the heartbeat with your hand. If the rhythms are the same, you may be listening to the same baby. If the rhythms are not exactly the same, you may be hearing two different babies (Figure 10.6).

- If you do not have a helper, but you have a watch with a second hand, or a homemade timer, try timing each heartbeat separately. If the heartbeats are not the same, you may be hearing two different babies.

Because twin births are often more difficult or dangerous than single births, it is safer for the woman to go to a hospital to give birth. Since twins are more likely to be born early, the mother should try to have transportation ready at all times after the 6th month. If the hospital is far away, the mother may wish to move closer in the last months of pregnancy. Be sure to have a plan for how to get help in an emergency.

The mother may have diabetes

You learned about the warning signs of diabetes in Study Session 9.

If a woman had all the warning signs of diabetes, what would you expect to find?

Refer the woman to a health centre if you suspect she may have diabetes.

Refer the woman to a health centre if you suspect she may have diabetes.She had diabetes in a past pregnancy. One of her past babies was born very big (more than 4 kilograms), or was ill or died at birth and no one knows why. She is fat. She is thirsty all the time. She has frequent itching and a bad smell coming from her vagina. Her wounds heal slowly. She has to urinate more often than other pregnant women. Her uterus is bigger than normal for how many months she has been pregnant. She has sugar in her urine when you do the dipstick test (Section 9.8.1 of Study Session 9).

Too much water in the uterus

Too much water (amniotic fluid) is not always a problem, but it can cause the uterus to stretch too much. Then the uterus cannot contract enough to push the baby out, or to stop the bleeding after the birth. In rare cases, it can mean that the baby will have birth defects. Try to refer the woman to the nearest health facility that can give her a sonogram (ultrasound examination) if the uterus is measuring too big and you do not suspect twins.

Molar pregnancy (tumour)

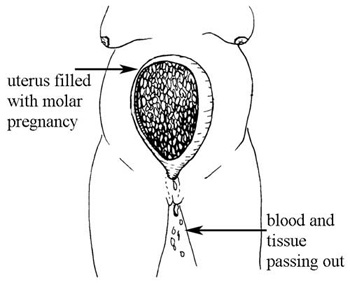

Sometimes a woman gets pregnant, but a tumour grows instead of a baby. This is called a molar pregnancy (Figure 10.7). Blood spotting and tissue (sometimes shaped like grapes) may be discharged from her vagina.

If you detect the signs and symptoms of a molar pregnancy, refer the woman to a hospital as soon as possible. The tumour can become a cancer and kill her, sometimes very quickly. A surgeon can remove the tumour to save the woman’s life.

Other signs of a molar pregnancy are that:

- No fetal heartbeat can be heard.

- No baby can be felt.

- The woman has had nausea all through the pregnancy.

- She has spotting of blood, and tissue shaped like bunches of grapes coming from her vagina.

10.3.3 The uterus is growing too slowly

Slow growth can be a sign of one of these problems:

- The mother may have too little water (amniotic fluid) in the uterus. Sometimes there is less water than usual, and everything is still OK. At other times, too little water can mean the baby is not normal, or will have problems during the labour.

- The mother may have a poor diet. Find out what kind of food the mother has been eating. If she is too poor to get enough good food, try to find some way to help her and her baby. Healthy mothers and children make the whole community stronger.

- The mother may have high blood pressure (hypertension). High blood pressure can keep the baby from getting the nutrition it needs to grow well. You learned how to check her blood pressure in the previous study session.

- The mother may be drinking alcohol, smoking, or using drugs. These can cause a baby to be small. Try to find some way to help her to stop these damaging behaviours.

- The baby may be dead. Dead babies do not grow, so the uterus stops getting bigger.

![]() If you do not have the right equipment to check her blood pressure, and the uterus is growing too slowly, refer her to the nearest health centre for evaluation.

If you do not have the right equipment to check her blood pressure, and the uterus is growing too slowly, refer her to the nearest health centre for evaluation.

How to tell if the baby is dead

If you suspect that the baby may have died, refer the mother to a health centre for the stillbirth.

If the mother is five months pregnant or more, ask if she has felt the baby move recently. If the baby has not moved for two days, something may be wrong. If the mother is more than seven months pregnant, or if you heard the baby’s heartbeat at an earlier visit, listen for the heartbeat again.

If the woman reports no fetal movements and you cannot hear the heartbeat, the baby may have died. If so, it is important for a dead baby (stillbirth) to be delivered soon, because the woman may bleed more than other mothers, and she is at more risk of infection.

When a mother loses a baby, she needs love, care and understanding (Figure 10.8). Make sure that she does not go through labour alone. If she gives birth to a dead baby in the hospital, someone she trusts should stay there with her during the birth.

10.4 Conclusion

In this study session, you have learned how to measure the fundal height, using your fingers and a measuring tape. You have also learned to interpret of your measurements and take the appropriate actions. In the next study session you will learn how to assess the position of the baby by palpating (feeling) the mother’s abdomen and listening to the position of the fetal heartbeat.

Summary of Study Session 10

In Study Session 10, you have learned that:

- Measuring the fundal height tells you the duration of the pregnancy, how fast the baby is growing, and the probable due date.

- Remember to position the woman correctly before measuring the fundal height. The fundus of the uterus grows on average two finger-widths for each month of pregnancy.

- If the fundal height is not equal to the gestational age, you need to check the duration of pregnancy from the last normal menstrual period (LNMP). Having the wrong date is one of the main reasons for discrepancy between fundal height and gestational age.

- If the fundal height is bigger than expected for gestational age, the mother may have given you the wrong LNMP, or she may have twins, diabetes, too much water in the uterus, or a molar pregnancy.

- If the fundal height is smaller than expected for gestational age, the mother may have given you the wrong LNMP, she may have too little amniotic fluid surrounding the fetus, raised blood pressure, poor nutrition, she may be drinking alcohol or taking other harmful drugs, or the baby may be dead.

Self-Assessment Questions (SAQs) for Study Session 10

Now that you have completed this study session, you can assess how well you have achieved its Learning Outcomes by answering the questions below Case Study 10.1. Write your answers in your Study Diary and discuss them with your Tutor at the next Study Support Meeting. You can check your answers with the Notes on the Self-Assessment Questions at the end of this Module.

Case Study 10.1 Abebech

Abebech is a pregnant woman, whose duration of gestation based on her last normal menstrual period (LNMP) is six months. When you examine her, you can feel that the fundus is four finger-widths above her bellybutton and you can hear a fetal heartbeat clearly.

SAQ 10.1 (tests Learning Outcomes 10.1 and 10.2)

- a.What is your assessment of the gestational age of Abebech’s baby using fundal height measurement?

- b.How many centimetres would Abebech’s abdomen measure from her pubic bone to the top of her uterus in order to confirm your fundal height measurement?

Answer

- a.The gestational age based on the fundal height measurement is seven months.

- b.If Abebech is really seven months pregnant, you would expect her abdomen to measure about 28 cm from her pubic bone to the top of the uterus, i.e. approximately one centimetre for each week of pregnancy dated from the LNMP. Remember the measurement may range from 26-30 cm.

SAQ 10.2 (tests Learning Outcome 10.3)

Is the gestational age of Abebech’s baby based on fundal height measurement consistent with the gestational age calculated from her LNMP?

Answer

The gestational age based on fundal height is one month more than expected from the date of the LNMP. Therefore, the uterus is bigger than expected from the date of the LNMP.

SAQ 10.3 (tests Learning Outcome 10.4)

What possible explanations can you give for your findings in Abebech’s case, and what actions should you take?

Answer

The uterus may be bigger than expected because the date of the LNMP may be incorrect, and Abebech is really seven months pregnant. This is not a problem, but it is important to investigate other possible explanations. For example, she may have too much amniotic fluid (water) surrounding the baby in the uterus; you should refer her to a health facility where she can have an ultrasound examination to find out if this is the problem. Or she could have a twin pregnancy. You can hear one fetal heartbeat clearly, so get someone else to help you listen to Abebech’s abdomen to see if you can hear two fetal heartbeats. If you suspect she is having twins, refer her to the nearest health facility.