Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Tuesday, 3 March 2026, 5:59 AM

Antenatal Care Module: 13. Providing Focused Antenatal Care

Study Session 13 Providing Focused Antenatal Care

Introduction

In Part 1 of the Antenatal Care Module, you have learned mainly about how the human reproductive system is structured anatomically and how it functions, the normal process and adaptation of pregnancy, the general assessment of the progress of pregnancy, and how to identify minor disorders. In Part 2 of the Antenatal Care Module, you will first learn about the basic principles of focused antenatal care (FANC).

This session will start by describing the concepts and principles of FANC and the basic differences between FANC and the traditional approach to antenatal care. It will highlight the other study sessions in Part 2 which all rest under the umbrella of FANC. You will also learn the objectives of each of the four FANC visits. The study session concludes with the preparations you and the pregnant woman should make for the birth, advice about what to do if complications arise, and instructions on how to write a referral note if she has to be transferred to a health facility.

Learning Outcomes for Study Session 13

When you have studied this session, you should be able to:

13.1 Define and use correctly all of the key words printed in bold. (SAQ 13.1)

13.2 Discuss the principles of focused antenatal care (FANC) and state how it differs from the traditional approach. (SAQ 13.1)

13.3 Describe the schedule, objectives and procedures covered in each of the four FANC visits for women in the basic component. (SAQs 13.2 and 13.3)

13.4 Advise pregnant women on birth preparedness, including the equipment they will need. (SAQ 13.4)

13.5 Summarise the main aspects of complication readiness and emergency planning, including advising blood donors and writing a referral note. (SAQ 13.3)

13.1 Focused antenatal care: concepts and principles

Historically, the traditional antenatal care service model was developed in the early 1900s. This model assumes that frequent visits and classifying pregnant women into low and high risk by predicting the complications ahead of time, is the best way to care for the mother and the fetus. The traditional approach was replaced by focused antenatal care (FANC) — a goal-oriented antenatal care approach, which was recommended by researchers in 2001 and adopted by the World Health Organization (WHO) in 2002. FANC is the accepted policy in Ethiopia.

FANC aims to promote the health of mothers and their babies through targeted assessments of pregnant women to facilitate:

- Identification and treatment of already established disease

- Early detection of complications and other potential problems that can affect the outcomes of pregnancy

- Prophylaxis and treatment for anaemia, malaria, and sexually transmitted infections (STIs) including HIV, urinary tract infections and tetanus. Prophylaxis refers to an intervention aimed at preventing a disease or disorder from occurring.

FANC also aims to give holistic individualised care to each woman to help maintain the normal progress of her pregnancy through timely guidance and advice on:

- Birth preparedness (described later in this study session),

- Nutrition, immunization, personal hygiene and family planning (Study Session 14)

- Counselling on danger symptoms that indicate the pregnant woman should get immediate help from a health professional (Study Session 15).

In FANC, health service providers give much emphasis to individualised assessment and the actions needed to make decisions about antenatal care by the provider and the pregnant woman together. As a result, rather than making the traditional frequent antenatal care visits as a routine activity for all, and categorising women based on routine risk indicators, the FANC service providers are guided by each woman’s individual situation.

This approach also makes pregnancy care a family responsibility. The health service provider discusses with the woman and her husband the possible complications that she may encounter; they plan together in preparation for the birth, and they discuss postnatal care and future childbirth issues. Pregnant women receive fundamental care at home and in the health institution; complications are detected early by the family and health service provider; and interventions are begun in good time, with better outcomes for the women and their babies.

Box 13.1 summarises the basic principles of FANC.

Box 13.1 Basic principles of focused antenatal care

- Antenatal care service providers make a thorough evaluation of the pregnant woman to identify and treat existing obstetric and medical problems.

- They administer prophylaxis as indicated, e.g. preventive measures for malaria, anaemia, nutritional deficiencies, sexually transmitted infections, including prevention of mother to child transmission of HIV (PMTCT, see Study Session 16), and tetanus.

- With the mother, they decide on where to have the follow-up antenatal visits, how frequent the visits should be, where to give birth and whom to be involved in the pregnancy and postpartum care.

- Provided that quality of care is given much emphasis during each visit, and couples are aware of the possible pregnancy risks, the majority of pregnancies progress without complication.

- However, no pregnancy is labelled as ‘risk-free’ till proved otherwise, because most pregnancy-related fatal and non-fatal complications are unpredictable and late pregnancy phenomena.

- Pregnant women and their husbands are seen as ‘risk identifiers’ after receiving counselling on danger symptoms, and they are also ‘collaborators’ with the health service by accepting and practising your recommendations.

13.1.1 Advantages of FANC

FANC is gaining much popularity because of its effectiveness in terms of reducing maternal and perinatal mortality (deaths) and morbidity (disease, disorder or disability). ‘Peri’ means ‘around the time of’, so perinatal means around the time of birth. Perinatal mortality refers to the total number of stillbirths (babies born dead after the 28th week of gestation) plus the total number of neonates (newborns) who die in the first 7 days of life. The perinatal mortality rate is the number of stillbirths and neonatal deaths that occur in every 1000 live births, and is an internationally recognised measure of the quality of antenatal care.

What is the definition of the maternal mortality ratio (MMR)? (You learned this in Study Session 1 of this Module.)

MMR is the total number of women dying from complications due to pregnancy or childbirth in every 100,000 live births.

FANC is the best approach for resource-limited countries where health professionals are few and health infrastructures are limited. In particular, the majority of pregnant women can’t afford the cost incurred by the frequent antenatal visits required by the traditional antenatal care approach. From the logistical and financial point of view, the traditional approach is not practical for the majority of pregnant women and is a burden on the healthcare system. As a result, many developing countries, including Ethiopia, are adopting the FANC approach.

13.1.2 Failings of the traditional approach to antenatal care

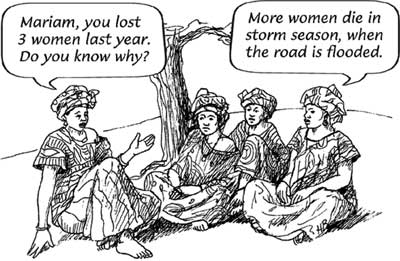

Research studies (for example, see Box 13.2) have shown that the more frequent antenatal visits traditionally practised do not improve pregnancy outcomes. In particular, pregnant women labelled as ‘low-risk’ or ‘not at risk’ in traditional antenatal care may not receive counselling on danger symptoms. As a result, it is very common that these women fail to recognise the danger symptoms and do not report soon enough to health professionals.

Box 13.2 Failure to identify ‘at risk’ pregnancies

Taking obstructed labour occurrence as one of indicators, a study in Zaire in 1984 in 3,614 pregnant women showed that 71% of the women who developed obstructed labour were previously categorised as ‘not at risk’, while 90% of women who were identified as ‘at risk’ did not develop obstructed labour. This is one source of evidence to show that most pregnancy problems are unpredictable and late phenomena.

Other examples of unpredictable pregnancy disorders that appear very late in gestation include the top three killers of mothers:

- Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy (hypertension means high blood pressure), specifically eclampsia, which commonly occurs very late in pregnancy, or during labour or after delivery (you will learn about this in Study Session 19).

- Haemorrhage (heavy bleeding), which occurs most commonly in the third trimester (Study Session 21 describes late pregnancy bleeding), or the more often fatal postpartum haemorrhage, which occurs after delivery (you will learn about this in the Labour and Delivery Care Module).

- Pregnancy related infection (postpartum infection of the uterus), which usually develops after delivery (this is described in the Labour and Delivery Care Module).

The traditional approach to antenatal care is unable to identify accurately women who are ‘at risk’ of developing any of these life-threatening conditions. It identifies some women as being ‘low risk’ who subsequently develop danger symptoms that need urgent professional intervention.

13.1.3 Comparions of traditional and focused antenatal care

Table 13.1 summarises the basic differences between the traditional and focused antenatal care approaches.

Substance use includes tobacco, alcohol, khat, illegal drugs, hashish, cocaine and others

| Characteristics | Traditional antenatal care | Focused antenatal care |

|---|---|---|

| Number of visits | 16–18 regardless of risk status | 4 for women categorised in the basic component (as described later in this study session) |

| Approach | Vertical: only pregnancy issues are addressed by health providers | Integrated with PMTCT of HIV, counselling on danger symptoms, risk of substance use, HIV testing, malaria prevention, nutrition, vaccination, etc. |

| Assumption | More frequent visits for all and categorising into high/low risk helps to detect problems. Assumes that the more the number of visits, the better the outcomes | Assumes all pregnancies are potentially ‘at risk’. Targeted and individualised visits help to detect problems |

| Use of risk indicators | Relies on routine risk indicators, such as maternal height <150 cm, weight <50 kg, leg oedema, malpresentations before 36 weeks, etc. | Does not rely on routine risk indicators. Assumes that risks to the mother and fetus will be identified in due course |

| Prepares the family | To be solely dependent on health service providers | Shared responsibility for complication readiness and birth preparedness |

| Communication | One-way communication (health education) with pregnant women only | Two-way communication (counselling) with pregnant women and their husbands |

| Cost and time | Incurs much cost and time to the pregnant women and health service providers, because this approach is not selective | Less costly and more time efficient. Since majority of pregnancies progress smoothly, very few need frequent visits and referral |

| Implication | Opens room for ignorance by the health service provider and by the family in those not labelled ‘at risk’, and makes the family unaware and reluctant when complications occur | Alerts health service providers and family in all pregnancies for potential complications which may occur at any time |

13.2 Important elements of FANC

FANC has the following three stages:

- Thorough evaluation (history taking, physical examination and basic investigations)

- Intervention (prevention/prophylaxis and treatment)

- Promotion (health education/counselling and health service dissemination).

Box 13.3 summarises the steps in this process.

Box 13.3 Basic steps in the FANC service

- Gather information (take history) by talking with the mother, check the mother’s body and check the fetus (physical examination and tests), as you learned in Study Sessions 8 to 11 of this Module.

- Interpret the gathered information (make a diagnosis) and evaluate any risk factors.

- Make an individualised care plan. If no abnormalities are identified, the care plan will focus on counselling, birth preparedness and complication readiness. If the mother needs specialised care, the plan will be to refer her to a higher health facility.

- Follow the care plan — in subsequent visits, you may be able to take care of the woman yourself by providing treatments and counselling, or you may need to refer her.

In provision of the FANC service, important elements to be considered are:

- Keeping privacy and confidentiality; effective communication builds trust and fosters confidence, so you should talk with women and their husbands in a manner that encourages communication about birth preparedness, complication readiness, HIV prevention, care and treatment.

- Continuous care is provided by the same provider for pregnant women in the community; in the context of this curriculum, you are the skilled health care provider for the pregnant women without identified complications in your community.

- Promotion of involvement of the woman’s partner or support person in the process of antenatal care and in preparations for the delivery.

- Provision of routine antenatal care services according to the national protocols, which will be described later in this study session).

- Linking of antenatal and postnatal care with prevention of mother to child transmission of HIV (PMTCT) and provision of family planning services.

13.3 The basic and specialised components of FANC

The FANC model divides pregnant women into two groups: those eligible to receive routine antenatal care (called the basic component), and those who need special care based on their specific health conditions or risk factors (the specialised component). Pre-set criteria (described below) are used to determine the eligibility of women to join the basic component. Women selected for the basic component are considered not to require any further assessment or special care at the time of the first visit, regardless of the gestational age at which they start the antenatal care programme.

Women are questioned and examined at the first antenatal visit to see if they have any of the following risk factors:

Previous pregnancy:

- Ended in stillbirth or neonatal loss

- History of three or more consecutive spontaneous abortions

- A low birth weight baby (<2500 g) or a large baby (>400 g)

- Hospital admission for hypertension, pre-eclampsia or eclampsia. (You will learn about these conditions in Study Session 19.)

Current pregnancy:

- Diagnosed or suspected twins, or a higher number of multiple pregnancies

- Maternal age less than 16 years or more than 40 years

- Mother has blood type Rhesus-negative: this can result in serious harm to the fetus if it is Rhesus-positive, because the mother makes antibodies which can cross the placenta and attack the baby’s tissues

- Mother has vaginal bleeding, or a growth in her pelvis

- Mother’s diastolic blood pressure (the bottom number) is 90 mmHg or more

- Mother currently has diabetes, heart disease, kidney disease, cancer, hypertension or any severe communicable disease such as TB, malaria, HIV/AIDS or another sexually transmitted infection (STI).

![]() A ‘YES’ to any ONE of the above questions means that the woman is not eligible for the basic component of antenatal care. She is categorised in the specialised component and requires more close follow-up and referral to specialty care.

A ‘YES’ to any ONE of the above questions means that the woman is not eligible for the basic component of antenatal care. She is categorised in the specialised component and requires more close follow-up and referral to specialty care.

You will refer women in the specialised component to a higher level health facility for additional monitoring and specialised care determined by specialists in these areas, while you continue to follow the activities of the basic component with these women.

13.4 The Antenatal Care Card

Figure 13.1 is a guide to the information that you should gather at each of the four antenatal visits. At the beginning of each visit, ask the mother if she has developed any danger symptoms since her last check up. Remind her to come to see you quickly if she develops vaginal bleeding, blurred vision, abdominal pain, fever or any other danger symptoms. You will learn how to counsel her about danger symptoms in Study Session 15.

13.5 Objectives and procedures at each FANC visit

Sometimes a pregnant woman comes for the first antenatal check-up when the pregnancy is already advanced, but you should cover all the steps in the basic care plan and all of the first visit activities even if she is already in the second or third trimester.

13.5.1 The first FANC visit

The first FANC visit should ideally occur before 16 weeks of pregnancy. You are expected to achieve the following objectives:

- Determine the woman’s medical and obstetric history (using the techniques you learned in Study Session 8) in order to collect evidence of her eligibility to follow the basic component of FANC, or determine if she needs special care and/or referral to a higher health facility.

- Perform basic examinations (pulse rate, blood pressure, respiration rate, temperature, pallor, etc.).

- If you think the pregnancy is beyond the first trimester, try to determine the gestational age of the fetus by measuring fundal height using the methods you learned in Study Session 10.

- Provide nutritional advice and routine iron and folate supplementation (the dosage is in Study Session 14). Advising against misconceptions about diet is also important. For example, in some parts of Ethiopia it is thought that eating eggs and meat during pregnancy will cause vernix (the sticky white substance on the baby’s skin at birth), and that vernix is dirty. In fact, eggs and meat are important sources of protein for the mother and the developing fetus, and vernix is good for the baby because it protects the baby’s skin.

- Provide HIV counselling and PMTCT services (you will learn how to do this in Study Session 16).

- Give advice on malaria prevention and if necessary provide insecticide-treated bed nets (ITNs). You will learn more about malaria prevention and treatment in Study Session 18.

- Check her urine for sugar using the dipstick test you learned about in Study Session 9, or refer her to the health facility if you suspect she may be developing diabetes.

- Advise her and her partner to save money in case you need to refer her, especially if there is an emergency requiring transport to a health facility. She may also need money for additional drugs and treatments. Financial help may be available from local community organisations like women’s groups.

- Provide specific answers to the woman’s questions or concerns, or those of her partner.

What could it mean if there is a difference of several weeks between the gestational age estimated from fundal height measurement and the estimate based on last normal menstrual period (LNMP)?

As you learned in Study Session 10, this may mean that the woman has not remembered the date of her LMNP correctly, but it could also mean that the fetus is not growing normally (fundal height lower than LNMP estimate), or there could be too much amniotic fluid around the fetus, or a twin pregnancy or very big baby (fundal height larger than LNMP estimate.)

13.5.2 The second FANC visit

Schedule the second FANC visit at 24-28 weeks of pregnancy. Follow the procedures already described for the first visit. In addition:

- Address any complaints and concerns of the pregnant woman and her partner.

- For first-time mothers and anyone with a history of hypertension or pre-eclampsia/eclampsia), perform the dipstick test for protein in the urine. (You will learn how to do this in Study Session 19 of this Module.)

- Review and if necessary modify her individualised care plan.

- Give advice on any sources of social or financial support that may be available in her community.

13.5.3 The third FANC visit

The third FANC visit should take place around 30–32 weeks of gestation. The objectives of the third visit are the same as those of the second visit. In addition you should:

- Direct special attention toward signs of multiple pregnancies and refer her if you suspect there is more than one fetus.

- Review the birth preparedness and the complication readiness plan (discussed later in this study session).

- Perform the dipstick test for protein in the urine for all pregnant women (since hypertensive disorders of pregnancy are unpredictable and late pregnancy phenomena).

- Decide on the need for referral based on your updated risk assessment.

- Give advice on family planning (Study Session 14).

- Encourage the woman to consider exclusive breastfeeding for her baby (Study Session 14).

Remember that some women will go into labour before the next scheduled visit. Advise all women to call you at once, or come to you, as soon as they go into labour. Don’t wait!

You should also emphasise the importance of the first postnatal visit to ensure that the woman is seen by you either at her home or at the Health Post as soon as possible after the birth. The most critical postnatal period for the mother is the first 4 hours; this is when most cases of postpartum haemorrhage (PPH) occur. (You will learn about PPH in the Labour and Delivery Care Module.)

13.5.4 The fourth FANC visit

The fourth FANC visit should be the final one for women in the basic component and should occur between weeks 36-40 of gestation. You should cover all the activities already described for the third visit. In addition:

- The abdominal examination should confirm fetal lie and presentation, as you learned in Study Session 10 and 11 and in your practical training classes. At this visit, it is extremely important that you discover women with a baby in breech presentation or a transverse lie and refer her to the nearest health facility for obstetric evaluation.

- The individualised birth plan (Box 13.4) should be reviewed to check that it covers all aspects of birth preparedness, complication readiness and emergency planning, as described in the next section.

- Provide the woman with advice on signs of normal labour and pregnancy-related emergencies (described in Study Session 15) and how to deal with them, including where she should go for assistance.

What is meant by breech presentation, and what is a transverse lie? (You learned this in Study Session 11.)

Breech presentation is when the baby is ‘head up’ in the uterus near the end of gestation, with its buttocks, feet or legs pushing down into the mother’s cervix. A transverse lie is when the baby is lying sideways across the abdomen.

![]() A baby in the breech presentation may be delivered through the vagina in a health facility. A baby in the transverse lie can only be corrected into the normal ‘head first’ or vertex presentation by an obstetric specialist, or it must be delivered by caesarean surgery.

A baby in the breech presentation may be delivered through the vagina in a health facility. A baby in the transverse lie can only be corrected into the normal ‘head first’ or vertex presentation by an obstetric specialist, or it must be delivered by caesarean surgery.

Box 13.4 Individualised birth plan

An individualised birth plan is a guide for healthcare providers developed in discussion with the individual woman and her partner or main support people which reflects their preferences about the planned birth. Some couples choose to have their baby at home under your care because they see birth as a normal part of life. Others choose to have a hospital or health centre birth. The birth plan for HIV positive women should be to deliver in a health facility, according to the National Guideline for PMTCT of HIV (as described in Study Session 16 of this Module).

13.6 Birth preparedness, complication readiness and emergency planning

Birth preparedness is the process of planning for a normal birth. Complication readiness is anticipating the actions needed in case of an emergency. Emergency planning is the process of identify and agreeing all the actions that need to take place quickly in the event of an emergency, and that the details are understood by everyone involved, and the necessary arrangements are made. First we consider normal birth preparedness.

13.6.1 Normal birth preparedness

Educate the mother and her family to recognise the normal signs of labour. Delivery may occur days or even weeks before or after the expected due date based on the date of the last normal menstrual period. Knowing what labour means will help the mother know what will happen, and this in turn helps her feel comfortable and assured during the last days or weeks of her pregnancy.

Provide clear instructions on what to do when labour starts (e.g. in the event of cramping abdominal pain or leaking of amniotic fluid). Make sure that someone will call you or another skilled attendant for the birth as soon as possible. Support your verbal advice with written instructions in the local language.

Birth preparedness should also cover:

- Honoring her choices. You should give all the necessary information about safe and clean delivery, but ultimately you should respect a woman’s choice of where she wants to give birth and who she wants to be with her.

- Helping her to identify sources of support for her and her family during the birth and the immediate postnatal period.

- Planning for any additional costs associated with the birth.

- Preparing supplies for her care and the care of her newborn baby.

13.6.2 Birthing supplies the mother should prepare

The birthing supplies that a pregnant woman and her family should be advised to prepare before the delivery are listed below (and see Figure 13.2):

- Very clean cloths to put under the mother and for drying and covering the newborn

- New razor blade to cut the cord

- Very clean and new string to tie the cord

- Soap, a scrubbing brush and (if possible) medical alcohol for disinfection

- Clean water for drinking and for washing the mother and your hands

- Three large buckets or bowls

- Supplies for making rehydration drinks, ‘atmit’ or tea

- Flashlight if there is no electricity in the area.

13.6.3 Complication readiness and emergency planning

As noted earlier, complication readiness is the process of anticipating the actions needed in case of an emergency and making an emergency plan (Box 13.5). Pregnancy-related disorders such as high blood pressure and bleeding can begin any time between visits for antenatal check-ups, and any other illness may occur during the pregnancy. If such conditions are suspected at any stage, you should refer the woman immediately, and repeatedly counsel her to report to you or seek medical care quickly if danger symptoms are seen.

Box 13.5 In an emergency

Make sure the woman and her husband and other family members know where to seek help.

- Alert them to plan for transportation with vehicle owners.

- Advise them to save money for transportation, drugs and other treatments.

- Decide who will accompany her to the health facility.

- Decide who will care for her family while she is away.

- A pregnant woman may bleed massively (haemorrhage) during or after delivery and may need blood to be given to her. You should make sure that she or her husband identifies two healthy adult volunteers who agree to act as blood donors if she needs it. Reassure the potential blood donors that they will not be harmed by giving blood, and their general health will be assessed before donating.

An important aspect of emergency planning is to foresee possible sources of delay that could be overcome by good planning.

13.6.4 Causes of delay in getting emergency help

There are three types of delay, all of which can be serious for the mother and her baby:

- Delay in healthcare-seeking behaviour (delay in deciding to seek medical care),

- Delay in reaching a health facility

- Delay in getting the proper treatment.

These delays have many causes, including logistical and financial constraints, and lack of knowledge about maternal and newborn health issues. For example, the woman, her family or neighbours may feel that only the husband or another respected family member can give permission for the woman to send for you, or get urgent medical care at a health facility. But delay could threaten her life and that of her baby.

Delays in deciding to seek care may be caused by failure to recognise symptoms of complications, cost considerations, previous negative experiences with the healthcare system and transportation difficulties. Delays in reaching care may be created by the distance from a woman’s home to a facility or healthcare provider, the condition of roads, or a lack of emergency transportation.

Delays in receiving appropriate care may result from shortages of supplies and basic equipment, a lack of healthcare personnel, and poor skills of healthcare providers. The causes of these delays are common and predictable. However, in order to address them, women and families and the communities, providers and facilities that surround them must be prepared in advance and ready for rapid emergency action.

13.6.5 Making a referral

Finally, you need to know what to do if you are making a referral – sending a client for additional health services and specialised care at a higher level health facility. You should complete a referral form in full and sign and date it, then make sure it goes to the health facility with the patient; it also has a space for feedback to you by the health facility about what treatment they have given.

If you do not have the standard referral form, you should write a note to the health facility that contains the key information (Box 13.6).

Box 13.6 Referral note

- Date of the referral and time

- Name of the health facility you are sending the patient to

- Name, date of birth, ID number (if known) and address of the patient

- Relevant medical history of the patient

- Your findings from physical examinations and tests

- Your suspected diagnosis

- Any treatment you have given to the patient

- Your reason for referring the patient

- Your name, date and signature.

That concludes our discussion of focused antenatal care. In the study sessions that follow in this Module you will learn more about specialised aspects of antenatal care in specific contexts, including health promotion issues in pregnancy, counselling the pregnant woman about danger symptoms, PMTCT of HIV, the diagnosis and management of malaria, anaemia and urinary tract infections, hypertension, abortion and bleeding in early and late pregnancy. The Antenatal Care Module ends by describing how to set up an intravenous (IV) cannula and infusion tubing to give fluids directly into the blood stream, and how to insert a urinary catheter to drain the bladder of a pregnant woman. Your practical training sessions will ensure that you have achieved these competencies.

Summary of Study Session 13

In Study Session 13, you learned that:

- Focused antenatal care (FANC) segregates pregnant women into those eligible to receive routine ANC (the basic component) and those who need specialised care for specific health conditions or risk factors.

- FANC emphasises targeted and individualised care planning and birth planning.

- FANC makes the pregnant woman, with her husband and the family, participatory in identifying pregnancy related or unrelated complications, planning and decision-making on the future course of pregnancy.

- Until proved otherwise, no pregnancy is to be labelled as risk-free.

- A pregnant woman has four antenatal visits, each with specific objectives to promote FANC the health of the mother and the fetus, assess risks, and give early detection of complications.

- The first FANC visit should be before week 16 of pregnancy; it assesses the woman’s medical and obstetric history, physical examination and test results, to determine her eligibility to follow the basic component.

- The second FANC visit is at 24-28 weeks. The additional focus is on measuring blood pressure and fundal height to determine gestational age.

- The third FANC visit is at 30–32 weeks. The additional focus is on detecting multiple pregnancies.

- The fourth is the final FANC visit between weeks 36 and 40. The additional focus is on detecting breech presentation and transverse fetal lie, and signs of hypertensive disorders. Pay extra attention to informing women about birth preparedness, complication readiness and emergency planning.

- Complication readiness and emergency planning anticipates and prepares for the actions needed in case of an emergency, including organising transport, money, support persons and blood donors, and reducing sources of delay in getting to the higher level health facility.

- Women who need to be referred at any stage during the pregnancy, or when labour begins, should be accompanied by a referral note with all relevant details of their history, diagnosis and treatment.

Self-Assessment Questions (SAQs) for Study Session 13

Now that you have completed this study session, you can assess how well you have achieved its Learning Outcomes by answering these questions. Write your answers in your Study Diary and discuss them with your Tutor at the next Study Support Meeting. You can check your answers with the Notes on the Self-Assessment Questions at the end of this Module.

SAQ 13.1 (tests Learning Outcomes 13.1, 13.2 and 13.4)

Which of the following statements is false? In each case, explain what is incorrect.

A Focused antenatal care focuses on the pregnant woman alone.

B Women in the basic component receive only 4 FANC visits, unless warning signs or symptoms are detected at any stage.

C Pregnant women do not need to prepare any equipment for labour and delivery.

D The birth plan in FANC is essentially the same for every woman and she is told about it at the fourth visit.

E Prophylaxis in FANC focuses on prevention of sexually transmitted infections, including mother to child transmission of HIV, malaria, nutritional deficiencies, anaemia and tetanus.

Answer

A is false. Focused antenatal care does not focus on the pregnant woman alone (this used to happen in the traditional approach). FANC includes the woman’s partner and if possible the whole family in caring for her during pregnancy, watching for danger symptoms, and preparing for the birth, complication readiness and emergency planning.

B is true. Women in the basic component receive only 4 FANC visits, unless warning signs or symptoms are detected at any stage.

C is false. A pregnant woman should prepare for labour and delivery by assembling very clean cloths, a new razor blade, very clean new string, soap and a scrubbing brush, clean water for washing and drinking, buckets and bowls, supplies for making drinks, and a flashlight.

D is false. The birth plan in FANC is individualised for every woman and her partner and respects her wishes and preferences. It is discussed at the third visit and revised if necessary at the fourth visit.

E is true. Prophylaxis in FANC focuses on prevention of sexually transmitted infections, including mother to child transmission of HIV, malaria, nutritional deficiencies, anaemia, urinary tract infections and tetanus.

SAQ 13.2 (tests Learning Outcomes 13.3 and 13.5)

Suppose a 27-year-old pregnant woman called Aster comes to see you. She tells you that this is her first pregnancy and the last time she saw her menstrual period was 25 weeks ago. What actions do you take during this first visit? When would you normally see her for the next visit?

Answer

As Aster is already 25 weeks pregnant, you should cover all the services of the first and the second FANC visits. Give close attention to investigating her medical and obstetric history and do a complete physical examination, including blood pressure, pulse, temperature, respiration rate, abdominal examination to measure fundal height, listen to the fetal heart beat, check for presentation and lie of the fetus, and check the results of urine tests. The purpose is to determine Aster’s eligibility to follow the basic component of FANC. Also advise her on nutrition, hygiene and rest.

If she is healthy and the pregnancy appears to be progressing normally, tell her that the next visit should be at 30-32 weeks of pregnancy - but she must seek help at once if she experiences any of the danger symptoms such as bleeding or foul smelling discharge from her vagina, fever, blurred vision, or feeling dizzy and confused.

SAQ 13.3 (tests Learning Outcomes 13.3 and 13.5)

Suppose Aster comes to you at 32 weeks of her pregnancy. You discover that her blood pressure is 120/60 mmHg, she has mildly pale conjunctiva and the fundal height is measured as the 38 week size. What do these signs suggest and what actions would you take?

Answer

Pale conjunctiva suggests that Aster may be anaemic, so ask her about her nutrition - what does she eat and how much food does she get each day? Perform a multiple dipstick test on a sample of her urine to see if it contains excess sugar or protein. If her urine test is normal, counsel her on improving her nutrition and provide her with iron and folate tablets.

As the fundal height is much more than you would normally expect at 32 weeks, it may indicate twins or a pathological condition and Aster should be referred for evaluation at a higher level of care. Therefore you should write a referral note and advise her to go to the nearest health centre or hospital. She may need help in arranging transportation or money for the trip. Advise her about birth preparedness, complication readiness and emergency planning.