Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Thursday, 5 February 2026, 5:53 AM

Antenatal Care Module: 16. Antenatal Interventions to Reduce Mother to Child Transmission of HIV

Study Session 16 Antenatal Interventions to Reduce Mother to Child Transmission of HIV

Introduction

HIV (the Human Immunodeficiency Virus) destroys the body’s defences against other infections, which lead to death if the person is not treated appropriately with anti-HIV drugs. HIV is carried in the blood of an infected person and also appears in the genital tract of infected men and women. It can be transmitted from one person to another by unprotected sexual intercourse (sex without a condom) or by transfer of infected blood. The virus can also be transmitted from mother to child during pregnancy, during labour and delivery, and during breastfeeding.

It is important for you to counsel pregnant women about prevention of mother to child transmission (PMTCT) of HIV, and to test them for HIV, as a routine part of antenatal care. This study session explains what you need to know about PMTCT so you can discuss it effectively with pregnant women during antenatal visits. We also tell you about a blood test for HIV, which will become available for you to use in women’s homes or at your Health Post. When you study the next two Modules in this curriculum, Labour and Delivery Care and Postnatal Care, you will learn about the policy and practice of PMTCT during those periods. The Module on Communicable Diseases covers HIV testing, prevention and treatment in the whole community. Here we focus on pregnant women before they give birth.

Learning Outcomes for Study Session 16

When you have studied this session, you should be able to:

16.1 Define and use correctly all of the key terms printed in bold. (SAQ 16.1)

16.2 Describe the factors that increase HIV transmission from mother to child during the antenatal period. (SAQ 16.2)

16.3 Provide a sensitive and effective HIV testing and counselling service to pregnant women. (SAQ 16.3)

16.4 Know how to use the opt-out approach to HIV testing and state the difference between the opt-in and opt-out approaches. (SAQ 16.4).

16.1 PMTCT of HIV in antenatal care

By prevention of mother to child transmission (PMTCT) of HIV we mean the set of interventions designed to reduce the transmission of HIV from HIV-infected pregnant women to their babies. Although HIV testing and counselling before pregnancy is important, you should always bear in mind that antenatal care may provide the first opportunity for testing and counselling women in your community regarding HIV. You should consider PMTCT as an essential component of focused antenatal care, as you learned in Study Session 13. It is an entry point for care and support not only for HIV-infected pregnant women, but also for their partners and newborn babies. Moreover, it will contribute to the attainment of the nationally shared Ethiopian vision of an ‘HIV-free generation by the year 2020’.

It is Ethiopian national policy to aim to test all pregnant women who give their informed consent. Informed consent means consent given by a person who is being offered medical testing or treatment, and who understands the risks and benefits of the procedures being offered. Even if the facilities and training to achieve the target of 100% of pregnant women HIV tested at Health Post level are not yet available, you need to know about HIV testing, and what treatment will be provided for HIV-infected women. This is so you can explain to them what will happen if they agree to be tested. We should emphasise that it is essential for pregnant women to give informed consent.

16.2 When does HIV transmission occur from mother to baby?

Although mother to child transmission (MTCT) of HIV can take place during pregnancy, the highest risk of transmission is during labour and delivery. Depending on breastfeeding practices and the duration of breastfeeding, there is also a substantial risk of MTCT of HIV during breastfeeding.

Without intervention, it is estimated that 40 out of every 100 babies (40%) born to HIV-infected mothers will be HIV-infected. Table 16.1 shows the risk of transmission during pregnancy, during labour and delivery, and during breastfeeding. Sixty percent of babies of HIV-infected mothers will not acquire the virus at all. However, it is not possible to predict which HIV-infected mother will transmit the virus to her child, so you must provide PMTCT services to all HIV-positive pregnant women.

| Transmission period | Maximum risk of HIV MTCT without any intervention |

|---|---|

| During pregnancy (in the uterus) | 5–10% |

| During labour and delivery | 10–15% |

| During breastfeeding after birth | 5–10% |

| Overall risk without breastfeeding | 15–25% |

| Overall risk with breastfeeding to 6 months | 20–35% |

| Overall risk with breastfeeding to 18-24 months | 30–45% |

| Total risk of MTCT | 20–40% |

Looking at the data in Table 16.1, how does the period of breastfeeding affect the risk of MTCT of HIV?

The longer the breastfeeding period, the greater the risk of MTCT of HIV. If a baby is breastfed to 6 months the risk of MTCT is 20-35%. The risk rises to 30-45% if breastfeeding goes on till the baby is 18-24 months old. This is a 10% rise in the risk of MTCT.

If HIV infection can be detected and treated effectively in the antenatal period, then it will reduce the chances of MTCT during labour and delivery or breastfeeding. Next, we look at the factors that increase the risk of MTCT during pregnancy.

16.3 Risk factors that increase the risk of HIV transmission during pregnancy

In HIV-positive pregnant women, the virus is found abundantly in the birth canal (cervix and vagina) and in the mother’s blood. Therefore, if the baby is exposed to vaginal fluid or to the mother’s blood during labour and delivery, there is an increased chance of MTCT occurring.

Normally, there is no direct mixing between the maternal and fetal blood in the uterus, as you learnt in Study Session 5. However, anything that breaks the barrier between the placenta and the wall of the uterus will increase the risk of MTCT of HIV. Box 16.1 lists some of the factors during pregnancy that can damage the barrier between maternal and fetal blood supply in the placenta, increasing the risk of MTCT. You will learn more about risk factors that increase the chance of MTCT of HIV during labour and delivery, and during lactation, in the next two Modules on Labour and Delivery Care and Postnatal Care.

Box 16.1 Damage to the barrier between fetal and maternal blood supply in the placenta

Common factors that damage the natural barrier between the fetal and maternal blood supply in the placenta and expose the fetus to maternal blood include:

- Infection of the placenta due to malaria, or by bacteria or viruses.

- Bleeding from the placenta before labour begins (the medical name for this is antepartum haemorrhage). This can occur due to placental abruption (placenta detaching too early from the uterus) or placenta previa (placenta covering the opening of the cervix). You will learn about these placental conditions in Study Session 21.

- Injury to the abdomen due to a blow, or by a sharp object which penetrates the abdomen.

- Vigorous abdominal massage by traditional healers in late third trimester. In some areas of Ethiopia, traditional healers repeatedly massage the abdomen, which they believe will make delivery of the baby easier.

- Maternal malnutrition, especially deficiency of vitamin C, vitamin A, or the mineral zinc.

- Cigarette smoking, which weakens the fetal membranes surrounding the unborn baby and increases the chance of developing placental abruption.

One question you may have is whether pregnancy affects HIV disease progression, or whether HIV disease progression affects pregnancy. So far, the evidence suggests that pregnancy does not make HIV worse. Similarly, there is no evidence that HIV infection leads to bad pregnancy outcomes.

16.4 PMTCT: core interventions

You should encourage all pregnant women to consent to be tested for HIV. You may be able to do the test yourself (see Section 16.5.1 below), but if you cannot carry out the test, it is available at all health centres and hospitals. Explain to every pregnant woman that if her HIV test result is positive, she can receive effective services to prevent her baby from getting HIV before or after birth. Tell her also that there is treatment for herself and her partner (if her partner is tested and found to be positive for HIV). The core PMTCT interventions are listed in Box 16.2.

Prophylaxis (pronounced ‘proff-ill-axis’) means ‘treatment aimed at prevention’. ARP drugs are given to prevent HIV from being transmitted from an HIV-infected mother to her baby.

Box 16.2 Core PMTCT interventions

- HIV testing and counselling. You will learn more about this later in this study session. (You learned about general counselling principles in Study Session 15.)

- Giving antiretroviral drugs (ARVs) to HIV-positive pregnant women. These drugs act against viruses such as HIV which belong to a virus ‘family’ called retroviruses. They are given either as part of antiretroviral therapy (ART) for women who are eligible to start treatment for their own HIV infection, or as antiretroviral prophylaxis (ARP) to pregnant women who are not eligible to start antiretroviral treatment at this time. Giving pregnant women ARV drugs either before or during pregnancy benefits them directly, but it also helps to prevent HIV transmission to the baby. According to the 2007 National PMTCT of HIV Guidelines for Ethiopia, ARP should be started at 28 weeks of gestation, but ART can be started at any time provided that the woman is eligible. (You will learn in detail about eligibility criteria for ART in the Communicable Diseases Module).

- Safe delivery practices. These are taught in the Module on Labour and Delivery Care.

- Safe baby feeding practices. You will learn about these in the Module on Integrated Management of Newborn and Childhood Illness.

16.4.1 Antiretroviral prophylaxis (ARP) and antiretroviral therapy (ART)

Antiretroviral prophylaxis (ARP) for prevention of mother to child transmission of HIV involves giving an antiretroviral drug to the mother starting at 28 weeks of gestation, again to the mother during labour and delivery, and to her baby immediately after its birth. The drug reduces the risk of transmission of HIV to the baby. It is different from the antiretroviral therapy (ART) given to the mother to treat her own HIV infection, depending on her eligibility criteria.

If an HIV-positive mother prefers and insists to deliver her baby at home, the current ARP drug that can be made available to her is called Nevirapine. When you know that an HIV-infected woman is near to giving birth at home, if you are authorised and trained to do so, you should give her a single dose of Nevirapine (200 mg) to take when true labour starts. It is better if you make the diagnosis of true labour and administer the drug yourself. Also, the baby should receive a single dose of Nevirapine within 3 days of being born. You should give this drug directly based on the baby’s weight. You will learn how to do this in the Communicable Diseases Module in this curriculum.

For those who decide to give birth in a health centre or hospital, three types of ARP drugs need to be taken by the labouring mother as prophylaxis (AZT + Neverapine + Lamuvudine). The woman and her husband have to know that the three ARP drugs administered during labour provide better protection for the baby. Additionally, the baby will be given two drugs (AZT + Lamuvudine) for 1-4 weeks. Therefore, you have to encourage HIV-positive women to give birth in health centres or hospitals.

The ARP drugs reduce the risk of MTCT of HIV to the baby, but they don’t treat the mother’s HIV infection and don’t improve her health. In some cases, the pregnant woman can start ART drug treatment for her HIV infection before she gives birth (if she is eligible). Therefore, you should try to encourage all HIV-infected pregnant women to go to the nearest health centre to check if they can start ART that will also protect their babies.

16.5 Routine HIV testing during pregnancy

It is advisable to carry out HIV testing on all pregnant women. The test is voluntary and, after receiving pre-test information, the woman has the right to refuse testing (as described later, in Section 16.5.2). A signed consent form is not needed in Ethiopia to conduct the HIV test — but obtaining clear verbal consent is essential.

The World Health Organization (WHO) and the health services in many countries, including Ethiopia, promote a policy of provider-initiated HIV testing and counselling. This means that when trained to do so, you should offer and provide HIV testing and counselling routinely as part of your maternal and child health services. You should not wait for the woman to ask for it (client-initiated HIV testing and counselling). If you have not been trained in these competencies, you should offer pre-test education and refer the woman to the nearest health centre, or inform her of a date for outreach testing.

16.5.1 Detecting HIV infection using blood tests

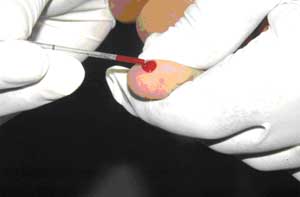

HIV infection can be detected in the blood by three tests. These include the HIV Rapid Test (or HIVRT), which is the only test which can be done in a person’s home or at a Health Post. The other two tests (the Western blot test and enzyme immunoassay test), can only be done at a higher level health facility. As it is so easy to use, the HIVRT is the most commonly used HIV test in Ethiopia. It involves taking a very small sample of blood from the person’s finger by pricking it with a sterile instrument, and taking a drop of blood to place onto a test kit (Figure 16.1). You will learn how to conduct the test and read the result in the Module on Communicable Diseases.

The principle behind all the various HIV testing kits that have been developed to screen blood is the same. The tests are highly sensitive for detecting HIV infection. They work by detecting antibodies (proteins produced by the body to fight infection) which appear in the blood after the window period of HIV infection. The window period is the period of time (up to 12 weeks or 3 months) between the virus entering a person’s body and the appearance of detectable antibodies in the person’ blood. In some cases, a person with a negative HIV test result may be infected, but the result fails to show up because they are in the window period of infection. Testing this person again after 3 months from the date of infection will usually reveal an HIV — positive result.

A small sample of the person’s blood is run through two HIVRT tests using kits from two different manufacturers. Can you suggest why the blood is tested twice using two different testing kits?

It increases confidence in the accuracy of the result if both tests are negative, or if both are positive. If the two results are different, it suggests that a test may not have been carried out correctly and a third test should be conducted as a ‘tie breaker’.

16.6 Steps in HIV testing and counselling

16.6.1 Opt-in and opt-out approaches

There are two contrasting approaches to counselling pregnant women about the need for HIV testing: they are known as ‘opt-in’ and ‘opt-out’. The opt-in approach involves counselling a woman for about 40 minutes in a private room, to inform her about everything she wants to know, so she can agree to be tested with informed consent (i.e. opt-in, or accepted by the woman). Of course, at the end of the counselling session, she may refuse to have the test. Opt-in was practised until 2006 in Ethiopia and is still the approach in many other countries.

The opt-out approach, on the other hand, involves informing the woman that she is about to have an HIV test. The main aim of the opt-out approach is to get as many women (and men) as possible tested for HIV infection. The differences between the opt-in and opt-out approaches are summarised in Table 16.2. As you can see, the opt-out approach is much more successful in achieving high test coverage than was the case with opt-in.

| Features | Opt-in | Opt-out |

|---|---|---|

| National PMTCT of HIV guideline | 2001 | 2007 |

| Counselling | Pre-test and post-test (before and after test; pre-test can take a long time till the client accepts the test) | Post-test (after the test result unless the client refused or opted-out) |

| Test take-up rate (number of persons tested) | Very low | Very high |

| Helps people to see the HIV test as normal | No | Yes |

Another big advantage of the opt-out approach is that HIV testing becomes a normal procedure for everyone. The normalisation of HIV testing helps to overcome fear of taking the test, so in the future it becomes just like any other routine test for any disease. Information about HIV testing can be presented in group sessions, which also helps to normalise it; for example, you may arrange a group meeting for pregnant women in your community to discuss aspects of focused antenatal care, and refer to the HIV test as a normal part of the routine visits. Finally, it is less time consuming for health workers, as it does not involve a long pre-test counselling session with each woman.

16.6.2 Counselling women who refuse HIV testing

There are some crucial points about the opt-out approach that you need to understand. First, the woman can refuse the test — she can opt-out. Second, if the HIV test result is positive, the woman will be given post-test counselling. Third, women who opted-out (refused) will be provided with a longer session of counselling, which starts by letting them express their concerns and reasons for objection to the test, so you can address their specific questions and worries.

In order to counsel opted-out women effectively you need to build trust. Emphasise that getting an early diagnosis and starting treatment or prophylaxis greatly improves the chances of survival for women who are HIV-positive and their babies. Knowing her HIV status does not necessarily mean a woman’s husband or partner has the right to know as well — it is her full right either to disclose her HIV status or to hide it. However, for better outcomes of follow-up and treatment, disclosing the truth to her family has a big advantage because they can support her. Assure the woman that HIV is no longer a disease that needs to be hidden, or one that people should be ashamed of. Also, it is not a disease that always leads to death, provided that people are diagnosed early and treatment is started early.

If a woman continues to refuse the HIV test, further counselling should be provided in subsequent antenatal care visits. She should be reassured that opting-out of HIV testing will not affect her access to antenatal care, labour and delivery care, postnatal care, or related services. Encourage her to reconsider testing. Do not pressure her to be tested, but let her know that if she changes her mind, an HIV test and further counselling can always be provided during a later visit. Document the reasons for her refusal in your notes as a reminder to offer her HIV counselling and testing the next time you see her. Box 16.3 summarises some common reasons why women refuse HIV testing.

Box 16.3 Common reasons why women refuse HIV testing

- Fear of being found HIV-positive and losing hope.

- Fear of a positive HIV result causing marriage disharmony and divorce.

- Fear of being found HIV-positive and not trusting the health professionals to keep the result private.

- Fear of a positive HIV test leading to stigma and discrimination by the community.

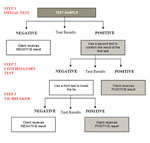

16.6.3 The HIV Rapid Test algorithm

An algorithm is a set of guidelines that enables you to follow the steps in a prescribed course of action, with pathways at each step depending on the results. Figure 16.2 shows you the algorithm approved for HIV Rapid Testing in Ethiopia.

As you can see from Figure 16.2, if the first test is positive, in order to be certain whether the client really is HIV infected, there is the need to conduct a second test to confirm the result of the first test.

What does the algorithm in Figure 16.2 say should happen if the second test is negative (it contradicts the result of the first test)?

The algorithm requires a third test to be conducted as a ‘tie-breaker’ — the third test will either confirm the positive result obtained by the first test, or it will confirm the negative result obtained by the second test.

Following the steps in the algorithm ensures that a positive test result has been clearly confirmed by two different tests before the result is given to the client.

16.6.4 Discussing HIV test results: post-test counselling

If a woman has agreed to, and has had the HIV test, you need to know how to discuss the results with her (and ideally also with her partner) during post-test counselling. In an adult, a positive HIV test result means that the person is definitely infected with HIV. As you will learn in a later Module, a positive test result in a newborn or very young baby may not mean that the baby is infected. The mother’s antibodies against HIV can get into the baby’s blood during labour and delivery, and it is impossible to tell from the HIV Rapid Test if it is detecting her antibodies or the baby’s antibodies. A negative HIV test result usually means that the mother or the baby is not infected with HIV.

A woman may be at high risk for HIV if she has recently had unprotected sexual intercourse with a man of unknown HIV status, or with a man known to be HIV-positive; or if her husband has another wife or has had other sexual partners, or if her husband injects illegal drugs. If such a woman tests negative the first time, she should be tested again after 3 months to confirm the original test result.

16.6.5 Post-test counselling for HIV-positive pregnant women

In talking to a woman after a positive HIV test result, you should be very sensitive to her feelings, which may include shock, anger or denial. When she is able to take in your health education messages, make sure that she understands:

- The importance of delivering her baby in a higher health facility where ARP drugs are available and safe delivery methods are practised, to prevent MTCT of HIV.

- She can reduce the risk of becoming ill by:

- Taking ART as prescribed and medicines to prevent opportunistic infections from developing

- Practising safe sex by using a condom with her partner to protect him from HIV infection, and to ensure she doesn’t get any other sexually transmitted infections (STIs) from him if he has unsafe sex with anyone else

- Eating enough nutritious food, as recommended for all pregnant women regardless of HIV status (see Study Session 14)

- Having good personal hygiene, as recommended for everyone to prevent infections with bacteria, viruses, protozoa and fungi, infestations with parasites and insects, and skin disorders.

- How to prevent MTCT of HIV to her baby (as you learned in this study session) including safe ways of feeding the baby (as you will learn in the Module on Integrated Management of Newborn and Childhood Illness).

- That the woman’s partner or husband and children should be tested for HIV.

- The importance of preventing HIV transmission to others and ways to do this.

- The importance of referrals for follow-up and ongoing HIV healthcare for herself, her partner, her HIV-exposed baby and other family members.

Opportunistic infections are infections caused by bacteria or viruses in people whose immune systems are weakened, for instance by HIV. A healthy person would normally be able to fight off infections by these bacteria or viruses.

16.6.6 Post-test counselling for HIV-negative pregnant women

Even though the woman will be very relieved that she has tested negative, you should ensure that she understands:

- How to remain HIV-negative through using safe sex practices.

- The need for later HIV testing if additional risk exposures occur, or if the test was done during the window period of early HIV infection.

- Exclusive breastfeeding for her baby (that is, just breastfeeding, no bottle-feeding or feeding of solid foods before 6 months of age).

- If she becomes HIV-infected during pregnancy or while breastfeeding, the baby has an increased risk of MTCT (see Table 16.1 above).

- The importance of effective family planning and birth spacing. (The Module on Family Planning will teach you all the details of different methods.)

16.6.7 Checklist for HIV testing and counselling during the antenatal period

Table 16.3 below summarises the steps involved in testing and counselling for HIV during the antenatal period, at the first antenatal visit and at every subsequent visit. We hope that you will find it helpful. Remember that you will also receive practical skills training in PMTCT of HIV, which will also cover policy and procedures during labour and delivery and the postnatal period.

| Ask, check | Result | Treat and counsel |

|---|---|---|

● Have you ever been tested for HIV? ● If yes, do you know the result? (Explain to the woman that she has the right not to disclose the result.) ● Has the partner been tested? | ● Known HIV-positive. | ● Ensure that she visited adequate staff and received necessary information about MTCT of HIV prevention ● Enquire about the ART or ARV prophylaxis and ensure that the woman knows when to start ● Enquire how she will be supplied with the drugs. ● Enquire about the infant feeding option chosen ● Advise on additional care during pregnancy, delivery and postpartum ● Advise on correct and consistent use of condoms ● Counsel on benefits of involving and testing the partner |

| ● No HIV test results or not willing to disclose result. | ● Provide key information on HIV ● Inform her about voluntary counselling and testing to determine HIV status ● Advise on correct and consistent use of condoms ● Counsel on benefits of involving and testing the partner | |

| ● Known HIV-negative | ● Provide key information on HIV ● Counsel on benefits of involving and testing her partner ● Counsel on the importance of staying negative by correct and consistent use of condoms |

16.8 Additional care for the HIV-positive woman during pregnancy

Finally, we should mention that a recent study in Ethiopia showed that most of the study participants believed that if HIV-infected women got pregnant, their general health would deteriorate because pregnancy accelerates HIV disease progression. As mentioned above, being pregnant does not mean that the healthy condition of the woman will deteriorate. However, maternal health may deteriorate during pregnancy because of the stage of HIV. If a woman gets pregnant when she has advanced HIV, she will certainly experience many health problems, including opportunistic infections. Therefore it is not being HIV-positive itself that should guide health service providers to give her additional care — it is the stage of the disease.

Summary of Study Session 16

In Study Session 16, you have learnt that:

- The common risk factors for increased chance of mother to child transmission of HIV during the antenatal period are: anything that breaks the normal barrier separating the maternal and fetal blood supply in the placenta, such as placental infection or bleeding, injury, vigorous abdominal massage, maternal malnutrition and cigarette smoking; exposure of the baby to infected vaginal fluid or maternal blood during labour and delivery; and prolonged exposure to HIV in breastmilk.

- PMTCT of HIV is offered as a routine component of standard maternal and child healthcare. It is the first stage in the ongoing prevention, treatment, care and support of HIV-positive pregnant women, their babies and partners.

- HIV testing and counselling is one of the core interventions of PMTCT of HIV. The others are: giving antiretroviral drugs to HIV-positive women and their newborn babies, safe delivery practices, and safe baby feeding practices.

- The opt-out provider-initiated counselling approach for HIV testing is more effective than the opt-in approach and is recommended by the Ethiopian national guidelines.

- The HIV Rapid Test (HIVRT) is the most commonly used HIV antibody test in Ethiopia and is suitable for blood testing in homes and at the Health Post.

- A positive HIV test result must be confirmed by a second test using a test kit from a different manufacturer. If the second test disagrees with the result of the first test, a third test is conducted as a ‘tie breaker’ using the HIV Rapid Test Algorithm (Figure 16.2).

- HIV-positive women should be strongly encouraged to give birth in a higher health facility where more advanced methods of PMTCT and additional ARP drugs (antiretroviral prophylaxis) can be given than are available at community level.

- Post-test counselling for HIV-positive and HIV-negative women should include advice about safe sex practices, encouraging the woman’s husband or partner to be tested for HIV, and the importance of family planning and birth spacing.

- HIV-positive pregnant women will need additional ongoing care and support, referrals and follow-up for themselves, their exposed babies, their partners and other family members.

Self-Assessment Questions (SAQs) for Study Session 16

Now that you have completed this study session, you can assess how well you have achieved its Learning Outcomes by answering these questions. Write your answers in your Study Diary and discuss them with your Tutor at the next Study Support Meeting. You can check your answers with the Notes on the Self-Assessment Questions at the end of this Module.

SAQ 16.1 (tests Learning Outcome 16.1)

A woman has sexual intercourse with a man who is HIV-positive. She is tested for HIV infection two weeks after this sexual intercourse. Her HIV test is negative.

- a.Should you trust this result? Give reasons for your answer.

- b.What should you do next?

Answer

- a.No, you should not trust the result. The woman could be in the window period of HIV infection, so the HIV test may give a negative result even if she was infected with HIV from this sexual intercourse.

- b.Counsel the woman to come for testing again after the end of the window period, which lasts around 12 weeks, and to use safer sex practices to ensure that she does not pass on HIV if she has become infected.

SAQ 16.2 (tests Learning Outcome 16.2)

Many factors increase the risk of MTCT during the antenatal period. What do these factors have in common? Give two examples.

Answer

Two factors are smoking, and injury to the abdomen, for example from a sharp instrument. (Note: You may have chosen other factors from those listed in Box 16.1.) What these factors have in common is that they may damage the barrier between the maternal and fetal blood supply in the placenta, allowing the blood from mother and fetus to mix. This increases the risk of mother to child transmission of HIV.

SAQ 16.3 (tests Learning Outcome 16.3)

A pregnant woman refuses an HIV test. Is there any more you can do?

Answer

If a pregnant woman refuses an HIV test, you can:

- Find out why she has refused — does she have any specific reasons for refusal? Address any specific questions and concerns she may have. Document this discussion. Build trust and deal with her concerns sensitively, for example about the impact on her family, fear of stigma and discrimination.

- Reassure her that the refusal to be tested will not affect her access to antenatal care, labour and delivery care, postnatal care, or related services.

- Provide pre-test counselling again in future antenatal visits.

SAQ 16.4 (tests Learning Outcome 16.4)

What are the main advantages of using the opt-out approach rather than the opt-in approach to HIV testing?

Answer

First, many more pregnant women are likely to accept HIV testing if the opt-out approach is adopted. Second, as more women are tested, the HIV test will come to be seen as more normal and acceptable as a routine part of antenatal care. Third, it is less time-consuming for health workers, as it does not involve a long pre-test counselling session with each woman.