Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Tuesday, 23 April 2024, 10:39 AM

Antenatal Care Module: 17. Premature Rupture of Membranes (PROM)

Study Session 17 Premature Rupture of Membranes (PROM)

Introduction

In this study session you will learn the definition, classification and risk factors of premature rupture of membranes (PROM). We will describe the potential complications that may end up with serious maternal morbidity and, at the worst, maternal mortality.

This session also tells you about the potential complications that endanger the life of the fetus and the newborn baby. You will learn how to make a clinical diagnosis of PROM and what actions you can take when you have women with PROM, building on your existing knowledge about leakage of fluid from the vagina as one of the danger symptoms in Study Session 15.

Learning Outcomes for Study Session 17

When you have studied this session, you should be able to:

17.1 Define and use correctly all of the key words printed in bold. (SAQ 17.1, 17.2 and 17.3)

17.2 Describe the classification of PROM. (SAQ 17.1 and 17.3)

17.3 Describe the different risk factors associated with PROM. (SAQ 17.2)

17.4 Define the diagnostic features of PROM. (SAQ 17.2)

17.5 Discuss the possible complications of PROM affecting the mother and the fetus. (SAQ 17.2 and 17.3)

17.6 Explain what action you need to undertake whenever you come across a woman with PROM. (SAQ 17.2 and 17.3)

17.1 Premature rupture of membranes

Premature rupture of membranes (PROM) is defined as a spontaneous leakage of amniotic fluid from the amniotic sac where the baby swims; the fluid escapes through ruptured fetal membranes, occurring after 28 weeks of gestation and at least one hour before the onset of true labour. PROM can occur before or after 40 weeks’ gestation, so the word ‘premature’ does not mean that the gestational age of the fetus is preterm.

Premature here refers to the premature rupture of fetal membranes before the onset of labour. PROM is of concern because rupture of fetal membranes before the onset of labour is not normal and is associated with many complications (described later in this session). In a normal labour, the fetal membranes usually rupture after the labour has progressed for some time, when the fetal head is deeply engaged and the cervix is near to full dilatation, with no complications in most labouring women. (You will learn in detail about labour progress in the next Module, Labour and Delivery Care.)

You need to know that the majority of people in Ethiopia don’t think of PROM as a problem. Rather, they consider the leakage of fluid as a good symptom about the coming labour. As you will see later in this study session, many serious complications can occur as a result of PROM. Therefore, you need to counsel the woman, her husband/partner and her family very clearly about the actions they should take if her membranes rupture and fluid leaks from her vagina before labour begins. Tell them about the dangers of waiting at home after the rupture of fetal membranes. We begin by describing how you classify cases of PROM, which determines how you handle each case.

17.2 Classifications of PROM

PROM is classified according to the gestational age at which it occurs and the interval between rupture of the fetal membranes and the onset of true labour.

Preterm PROM occurs after 28 weeks of gestational age and before 37 weeks.

Term PROM occurs after 37 completed weeks of gestational age, including post-term cases occurring after 40 weeks.

Preterm and term PROM are further divided into:

- Early PROM (less than 12 hours has passed since the rupture of fetal membranes)

- Prolonged PROM (12 or more hours has passed since the rupture of fetal membranes).

The major reason for classifying PROM into term, preterm, early and prolonged PROM is for effective management decisions. The earlier the occurrence (preterm PROM) and the longer the interval between the rupture of fetal membranes and onset of labour, the more complications there are likely to be. We will describe the actions you should take to manage cases of PROM in Section 17.6 of this study session. First, we discuss the risk factors for PROM and then the complications that can result for the mother and the fetus.

17.3 Risk factors for PROM

Rupture of fetal membranes can occur when the cervix is either closed or dilated. Sometimes, it can occur in a very early pregnancy (before 28 weeks – this leads to inevitable abortion, which you will learn about in Study Session 20), or in early third trimester (between 28 and 34 weeks). It is not exactly known why fetal membranes rupture before the onset of labour. However, there are some known risk factors highly associated with PROM.

Consider the amniotic cavity as a sac (or bag) whose wall is formed by the fetal membranes, enclosing the fetus and amniotic fluid. The sac will rupture at the weakest point, which is the part of the membranes in direct contact with the ‘mouth’ of the cervix. Rupture happens when the sac is either damaged by an infection or external trauma, or it becomes over-stretched (distended) and unable to withstand the internal pressure. These risk factors are described in more detail below.

17.3.1 Infection can cause PROM

Bacteria that cause infection in the lower genital tract (infection of the cervix or vaginal wall) can travel upwards through the cervix and infect the fetal membranes. This can weaken the membranes enough to allow them to rupture.

Box 17.1 summarises the diagnostic signs of infection in a woman with PROM.

Box 17.1 Evidence of infection in a woman with PROM

- Fever: the woman may complain of feeling feverish, or you may record her temperature of 38°C or more.

- The vaginal discharge may have an offensive smell and the colour may be changed from watery to cloudy.

- She may have an increased pulse rate (more than 100 beats/minute).

- The fetal heart beat may increase to 160 beats/minute or more.

- She may feel pain in the lower abdomen, particularly when it is touched.

17.3.2 Malpresentation of the fetus

Rupture of fetal membranes is highly associated with fetal malpresentations in the third trimester. Particularly high risk of PROM is associated with footling breech (feet first) and transverse lie (across the abdomen) with the baby’s back arched upwards and hands and legs pointing down, in direct contact with the weakest point of the membranes.

17.3.3 Multiple pregnancy and excess amniotic fluid

If the uterus holds two or more babies, or there is excess accumulation of amniotic fluid (polyhydramnios), the fetal membranes become over-stretched and rupture. The membranes can rupture even if the amount of amniotic fluid is small, if there is another cause such as those described below.

‘Poly’ means excess, ‘hydra’ means water, and ‘amnios’ refers to the amniotic fluid. So ‘polyhydramnios’ means ‘too much amniotic fluid’.

17.3.4 Cervical incompetence

Without uterine contraction, the cervix may dilate spontaneously early in gestation and this can be the cause for an abortion (miscarriage). The cervix may dilate even in late pregnancy before the onset of labour. As the cervix continues dilating, it will allow part of the fetal membranes to pass through it. As a result, the membranes can rupture easily and leak amniotic fluid.

17.3.5 Trauma to the abdomen

Any blunt or penetrating trauma to the abdominal wall can result in a break in the fetal membranes. Blunt traumas include: uterine manipulation by a doctor or midwife to change the fetal presentation from breech or transverse lie to the normal ‘head down’ or vertex presentation; uterine massage by traditional healers; and blunt abdominal injury (e.g. from a blow or fall). An example of a penetrating abdominal injury is insertion of a hollow needle into the amniotic cavity through the abdominal wall, or through the cervix, to withdraw amniotic fluid or placental tissue for analysis.

17.4 Diagnosis of PROM

When there is a rupture in the fetal membranes, the woman notices a painless sudden leakage of fluid from her vagina, which is usually excess and watery. However, when the amount of amniotic fluid in the sac is minimal, the leaking fluid may only wet her underwear, and you may be unsure whether to make the diagnosis of PROM from the woman’s complaint.

The mother may be worried, but not be sure whether the leakage is normal or abnormal. A little bit of excess vaginal discharge is normal near to full term, and this may be confused with the leakage of amniotic fluid. So you need to refer any woman complaining of excess vaginal discharge for further evaluation at a higher level health facility, in case the woman is showing signs of PROM.

Box 17.1 summarises the clinical features that can help you to make the diagnosis of PROM.

Box 17.1 Clinical features of PROM

- The woman complains of leakage of fluid from her vagina (minimal or excess).

- She says she noticed a decrease in the size of her abdomen after leakage of fluid.

- You observe watery fluid coming out through the vagina, or the woman’s under clothing is soaked with watery fluid.

- When you measure the distance between the pubic symphysis and the fundal height (as described in Study Session 9), you find the baby is small for gestational age. (Note that being ‘small for gestational age’ can also be due to scanty amount of amniotic fluid with intact membranes, intrauterine growth restriction and wrong date for the stated gestational age.)

- In PROM, the amniotic fluid remaining in the sac will be minimal, so you may be able to feel (palpate) the fetal parts easily through the mother’s abdomen.

- Although not specific, the woman may have an offensive smell due to vaginal discharge, and she may have a fever (see Box 17.1 above); these signs indicate an already established infection, which may be the cause of PROM.

- You can give her a dry vaginal pad or Goth and check after some hours whether it is wet or still dry. Note that being dry doesn’t necessarily rule out PROM.

17.5 Complications of PROM

PROM is associated with several potentially life-threatening complications, as we will now describe.

17.5.1 Infection after PROM

As stated earlier, the premature rupture of fetal membranes allows bacteria to get into the uterine cavity. They multiply rapidly in the warm, wet environment and, as a result, both the mother and the fetus may develop a life-threatening infection. It can continue even after the birth as uterine or widespread infection in the mother, and cause pneumonia, sepsis (blood infection) or meningitis (infection of the brain) in the newborn.

Infection is one of the most feared complications of PROM because, unless it is quickly treated, it may end up with both maternal and fetal or newborn death. But the good news is that swift treatment with antibiotics is generally successful.

It should be noted that prolonged PROM cases are highly likely to develop a uterine infection unless treated quickly with preventive antibiotics.

Why do you think prolonged PROM is particularly likely to lead to infection?

Over 12 hours have passed since the fetal membranes ruptured, so any bacteria that got into the uterus have enough time to multiply and take hold.

17.5.2 Cord prolapse

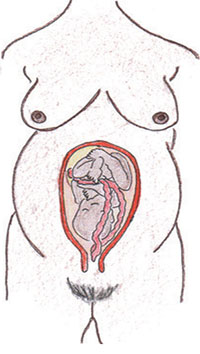

One of the potentially fatal complications of PROM for the baby is umbilical cord prolapse. (The term ‘prolapse’ means ‘pushing out of the proper place’.) When the membranes rupture, the umbilical cord may be washed downwards by the rushing out of amniotic fluid and fall towards the vagina. It may be pushed ahead of the baby and push out into the cervix (see Figure 17.1) through the break in the membranes. In this position, the prolapsed cord is easily compressed, cutting off the blood supply to the fetus and this can be the cause of sudden fetal death.

17.5.3 Fetal hypoxia and asphyxia

When the ruptured fetal membranes have leaked most of the fluid that keeps the fetus ‘floating’ in the uterus, the membranes collapse around the baby, and the baby can press against the uterine wall. It can lie on and compress the umbilical cord, so the fetus becomes short of oxygen and the waste product carbon dioxide builds up in its body.

Deficiency of oxygen and accumulation of carbon dioxide in the body is called hypoxia (literally ‘low oxygen’), which rapidly leads to asphyxia (brain and tissue damage due to hypoxia) resulting in death if oxygen is not quickly restored.

The fetus can also develop asphyxia and die because of partial or complete placental abruption, as described next.

17.5.4 Placental abruption

When the cause of the rupture of fetal membranes is an over-stretched uterus, there is a possibility of premature separation of the placenta from the uterine wall (a condition called placental abruption which you will learn more about in Study Session 21). This can happen when a gush of fluid suddenly flows out of the uterus, ripping part of the placenta away from the uterine wall.

17.5.5 Preterm labour

Once the fetal membranes rupture, labour usually starts spontaneously in less than one week. If the PROM occurs several weeks before the pregnancy reaches full term, the resulting labour will also be preterm, and this can pose a risk to the newborn. Its development may not be sufficiently mature to sustain life — for example, the preterm baby cannot maintain its body temperature as well as a full term baby, its respiration will be shallow, it may have trouble feeding and its immune system may not be able to protect it from infection.

17.5.6 Deformity of fetal limbs

Sometimes labour does not start spontaneously after PROM. This is the most risky situation for development of infection and fetal deformity, if it occurs too early in gestation and the pregnancy continues for a long period of time after the membranes have ruptured.

Without the amniotic fluid to keep the fetus ‘floating’, the muscular walls of the uterus closely surround the fetus and compress it. The immature fetal bones are not yet strong enough to resist the pressure, and the chance of developing deformity of the legs, feet, arms or hands is very high if the pregnancy continues in this state for more than 3 weeks.

17.6 Actions in a case of PROM

Whenever you see a woman with clearly defined or suspected PROM, the questions you need to answer are:

- Does the woman have established labour or not?

- If the woman has established labour:

- Is it preterm or term PROM?

- How long has she stayed at home after the membranes ruptured?

- How much has the labour progressed?

- Is the fetus alive or dead?

- Irrespective of labour condition, does the woman have established infection or not?

You need to answer the above questions because they show what actions you need to take, as we will now describe.

17.6.1 When should you conduct the delivery before referral?

Under certain conditions, it is safer for you to conduct the delivery of a woman with PROM where she is (at her home or your Health Post) before referral.

Can you explain why not?

It greatly increases the risk of infection getting into the uterus.

You should support her through the labour before referral if she is:

Don’t do an internal vaginal examination, even wearing surgical gloves, in a woman with PROM!

Don’t do an internal vaginal examination, even wearing surgical gloves, in a woman with PROM!

- already in established labour (yes to Question 1 above)

- and she came to you with a history of term PROM, after 37 completed weeks of gestation and the leakage of fluid happened before the onset of labour (Question 2)

- and you see no evidence of infection (no to Question 4).

If the labour and delivery was normal and the woman and baby are doing well, check them for the next 24 hours. Tell the family to call you and take her to a health facility immediately if there is any sign of infection in the mother or the newborn.

If the woman comes to you with PROM and she is already in established labour which has progressed a long way (late active first stage, or second stage when the woman is wanting to push), even with evidence of infection, or a preterm labour, or you think the fetus may be dead, it is still preferable to conduct the delivery where the woman is and refer her to a health facility as soon as the baby is born.

17.6.2 When should you refer before conducting the delivery?

Refer the woman with PROM as soon as possible to a hospital with a surgical facility if she is not in labour, or she is still in the early stage of labour and there is time to get her to the health facility before labour progresses much. Remember that if the case is preterm PROM, the newborn will need special care in a hospital.

Summary of Study Session 17

In Study Session 17, you learned that:

- Premature rupture of membranes (PROM) is a spontaneous rupture of fetal membranes and leakage of fluid from the vagina after 28 weeks of gestation and at least one hour before the onset of true labour.

- PROM is classified as preterm PROM when the leakage of fluid occurs before 37 completed weeks of gestation, and term PROM when it occurs after 37 weeks.

- Women with prolonged PROM (12 or more hours passed since the rupture of fetal membranes) are highly likely to develop infection in the uterus unless they get swift antibiotic treatment.

- The commonest risk factors for PROM include infection in the reproductive tract, fetal malpresentations (breech or transverse lie), multiple pregnancy, excess amniotic fluid, cervical incompetence, and abdominal trauma.

- The diagnosis of PROM is based on a history of sudden and painless leakage of moderate or excess watery fluid from the vagina. You may witness the woman’s soaked underwear, feel easily palpable fetal parts through her abdominal wall, and measure the uterine size as ‘small for gestational age’ because her abdomen has shrunk.

- The common complications of PROM are infection in the mother and/or the fetus/newborn, cord prolapse, intrauterine fetal asphyxia/death, placental abruption, preterm labour, and deformity of the fetal limbs.

- Fever, foul smelling vaginal discharge, increased maternal pulse rate, increased fetal heartbeat and lower abdominal pain are signs of infection in the uterine cavity, which needs to be treated quickly with antibiotics.

- To minimize the risk of infection, gloved digital pelvic examination should be avoided in women with PROM.

- Deliver the baby and then refer in cases of term or preterm PROM where the woman is already in advanced labour, even if there is evidence of infection or in cases of term PROM if labour has begun normally and there is no evidence of infection.

- Refer as soon as possible all women with PROM coming to you before the onset of labour, or in early labour, with established maternal or neonatal infection; refer all preterm babies immediately after delivery.

- Make sure that the woman with PROM and her family are well aware of the risks of waiting at home; counsel them to call you at once and take transport to the health facility.

Self-Assessment Questions (SAQs) for Study Session 17

Now that you have completed this study session, you can assess how well you have achieved its Learning Outcomes by answering the following questions. Write your answers in your Study Diary and discuss them with your Tutor at the next Study Support Meeting. You can check your answers with the Notes on the Self-Assessment Questions at the end of this Module.

SAQ 17.1 (tests Learning Outcomes 17.1 and 17.2)

Complete the missing information in Table 17.1.

| PROM classification | Gestational age |

|---|---|

| Preterm PROM | |

| Term PROM | |

| Interval since membranes ruptured | |

| Early PROM | |

| Prolonged PROM |

Answer

The completed Table 17.1 should look like this:

| PROM classification | Gestational age |

|---|---|

| Preterm PROM | After 28 weeks and before 37 weeks |

| Term PROM | After 37 weeks, including post-term (after 40 weeks) |

| Interval since membranes ruptured | |

| Early PROM | Less than 12 hours |

| Prolonged PROM | More than 12 hours |

SAQ 17.2 (tests Learning Outcomes 17.1, 17.3, 17.4 and 17.5)

Which of the following statements is false? In each case, explain what is incorrect.

A Infection in the uterus may cause PROM and may also be a complication following PROM.

B PROM may occur if the uterus is over-stretched by malpresentation of the fetus, multiple pregnancy or excess amniotic fluid.

C Cervical incompetence in combination with PROM can be a cause of umbilical cord prolapse.

D The fetal membranes are so strong that blunt trauma to the abdomen is unlikely to cause PROM.

E Hypoxia and asphyxia of the woman in labour is a common complication of prolonged PROM.

F A sudden gush of clear watery fluid from the vagina is always seen in cases of PROM.

Answer

A is true. Infection in the uterus may cause PROM and may also be a complication following PROM.

B is true. Prom may occur if the uterus is over-stretched by malpresentation of the fetus, multiple pregnancy or excess amniotic fluid.

C is true. Cervical incompetence in combination with PROM can be a cause of umbilical cord prolapse.

D is false. Blunt trauma to the abdomen is a common cause of PROM.

E is false. Hypoxia and asphyxia of the fetus (not the woman in labour) is a common complication of prolonged PROM.

F is false. Some cases of PROM occur without a sudden gush of clear watery fluid from the vagina, so you should always take account of other diagnostic signs such as reduction in size of the abdomen and clearly palpable fetal parts.

Read Case Study 17.1 and then answer the questions that follow it.

Case Study 17.1 Zufan’s story

Zufan’s family contact you to say that her waters broke 24 hours earlier, but they are concerned because her labour has not started yet. They think the baby was due to be born last week. She feels hot to the touch and is becoming restless and complaining of pain in her lower abdomen.

SAQ 17.3 (tests Learning Outcomes 17.1, 17.2, 17.5 and 17.6)

- a.How do you classify Zufan’s case of PROM?

- b.Does she have the signs of any complications?

- c.Is there anything you could have done to prevent her condition from worsening?

- d.What immediate action should you take?

Answer

- a.Zufan’s condition should be classified as post-term prolonged PROM, because the gestational age is already beyond 40 weeks and her membranes ruptured more than 12 hours ago.

- b.She has two clear signs of abdominal infection: fever and lower abdominal pain.

- c.You could have prevented her condition from worsening if you had counselled Zufan and her family more clearly about the risks of waiting at home after the membranes have ruptured.

- d.You should immediately refer her to the nearest hospital or health centre with surgical facilities; she will also need antibiotics quickly to treat the infection.