Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Sunday, 8 February 2026, 9:56 PM

Antenatal Care Module: 18. Common Medical Disorders in Pregnancy

Study Session 18 Common Medical Disorders in Pregnancy

Introduction

In this study session you will learn about three common medical disorders during pregnancy and their effects on the health of the pregnant woman: malaria, anaemia and urinary tract infections (or UTIs), and how to distinguish mild treatable UTIs from persistent infections of the bladder and serious disease affecting the kidneys. We will teach you about the causes of these conditions, their signs, symptoms, diagnosis and management, and when you should refer the woman to a health facility for further tests and treatment. And you will learn the best ways to prevent these conditions from occurring and why it is especially important to do this during pregnancy.

Learning Outcomes for Study Session 18

When you have studied this session, you should be able to:

18.1 Define and use correctly all of the key words typed in bold. (SAQs 18.1 and 18.2)

18.2 Describe the risks to the woman, the fetus and the newborn of malaria, anaemia and urinary tract infections (UTIs) in pregnancy. (SAQ 18.1)

18.3 Advise pregnant women and their male partners how to prevent malaria, anaemia and UTIs from occurring. (SAQ 18.2)

18.4 Identify the signs and symptoms of malaria in the pregnant woman, and know how to manage malaria in pregnancy and when to refer the woman to a health facility. (SAQ 18.2)

18.5 Identify the signs and symptoms of anaemia in the pregnant woman, and know how to manage anaemia in pregnancy and when to refer the woman to a health facility. (SAQ 18.2)

18.6 Identify and distinguish between the signs and symptoms of infections of the bladder and infections of the kidneys during pregnancy, manage mild UTIs in pregnancy with oral medicine and know when to refer a woman with persistent infection to a health facility. (SAQ 18.2)

18.1 Malaria in pregnancy

Malaria is an infection of the red blood cells caused by a parasite called plasmodium that is carried by certain kinds of mosquitoes. A mosquito sucks up the malaria parasites in the blood of an infected person when it takes a blood ‘meal’, and then passes the parasites on when it bites someone else (Figure 18.1). The parasites develop to maturity in the person’s red blood cells and millions of parasites collect in the placenta of a pregnant woman.

Malaria can be more severe in women who are sick with other illnesses. Malaria is more dangerous to pregnant women than to most other people. A pregnant woman with malaria is more likely to develop anaemia (as you will see later in this study session), have a miscarriage (spontaneous abortion of the fetus before 24 weeks of pregnancy), an early birth, a small baby, a stillbirth (baby born dead after the 24th week of pregnancy) or to die herself (maternal mortality).

18.1.1 Symptoms of malaria

The symptoms of a disease are the indications that an affected person is aware of and is able to tell you about; they may tell you spontaneously, but you may have to ask the right questions. The symptoms of malaria are:

- Chills (feeling unusually cold, shivering) and rigors (intense periods of shivering lasting several minutes and up to 1 hour); this is often the first symptom of an attack

- Headache and weakness often accompany the chills

- Fever (raised temperature); the fever often follows the chills, and the temperature may go so high that the person suffers delirium (not being in her right mind, seeing or hearing things that are not real)

- Sweating as the temperature falls

- Diarrhoea/vomiting may also be experienced in some cases

- Muscle/joint pain is another common symptom.

The periods of fever typically alternate with periods of chills and rigors in attacks that can occur every day, or every 2-3 days. All of these symptoms could be due to something else, but you should suspect malaria if they happen in a person who has been exposed to mosquitoes in an area where malaria is known to occur.

The signs of a disease are the indications that only a trained health professional would notice, or be able to detect by conducting a test. For example, if you suspect malaria, you should take the person’s temperature with a thermometer if you have one (you learned how to do this in Study Session 9), or by comparing your own temperature with the woman’s (Figure 18.2). In cases of malaria, the fever can go as high as 39-40°C or even higher.

What is the normal body temperature and what would be a sign of fever?

Normal body temperature is 37oC; a sign of fever would be a temperature of 38oC or above.

18.1.2 Diagnosis of malaria

There are two main ways to diagnose malaria using blood tests. The simplest way is to run a malaria rapid diagnostic test (RDT), which detects proteins produced by the parasite in the patient’s blood. The test kits can be in the form of a dipstick, a plastic cassette or a card, which changes colour when exposed to a drop of blood from an infected person – usually taken by pricking a finger with a sterile lance. However, the test kits must be stored carefully and protected from humidity and high temperatures. Training for health workers is required before the signs of malaria in the test results can be interpreted accurately.

The other way to diagnose malaria, which requires specialist training and equipment, is from microscopic examination of a smear of blood on a glass slide, which has been stained to reveal the parasites. Facilities for microscopic blood testing are usually not available at Health Post level. If you have been trained to use the malaria RDT and have access to properly stored test kits, you should diagnose malaria on the basis of the test results. If you are unable to use the malaria RDT, base your diagnosis on the symptoms (e.g. headache, fever, chills, muscle/joint pain), and high temperature measured with a thermometer.

18.1.3 Treatment of malaria in pregnancy

It is important for pregnant women to avoid malaria — or to be treated quickly if they get sick. Malaria medicines can have side-effects, but these medicines are much safer than actually getting sick with malaria. If a woman has symptoms of malaria, she should be treated right away. The medicine used in Ethiopia in the Health Extension Programme is called Artemether Lumifantrine (marketed as Coartem tablets). It works by interfering with the development of the parasites in the person’s red blood cells.

Coartem can be used to treat malaria during the second and third trimesters of pregnancy. The second trimester is 13-27 weeks since the woman’s last normal menstrual period (LNMP), and the third trimester is from 28 weeks until the birth at around 40 weeks. If the diagnostic test is positive for malaria, or you strongly suspect malaria based on the clinical signs and symptoms, and the woman is in either the second or third trimester, treat her as indicated in Box 18.1.

Box 18.1 Coartem treatment in the second or third trimester of pregnancy

- Four Coartem tablets twice a day (12 hours apart) for 3 days (a total of 24 tablets). Tell her to take the tablets with food, milk, oatmeal or soup. She can crush them and mix them with a spoonful of food if this makes it easier for her to swallow the medicine. Figure 18.3 shows a way of explaining to women how many tablets to take.

- You can also give her paracetamol tablets (500-1000 mg) every 4-6 hours to bring down her temperature when she has a fever.

- Cold sponging her body with a cloth dipped in cool water will also help when she has a fever.

- Advise the woman to drink plenty of fluids to make sure she does not become dehydrated. She should drink at least 1 large cup of fluid every hour.

![]() Pregnant women with suspected malaria in the first trimester, who are not too sick to travel, should be referred to the nearest health centre for specialist treatment.

Pregnant women with suspected malaria in the first trimester, who are not too sick to travel, should be referred to the nearest health centre for specialist treatment.

If the woman is in the first trimester (i.e. up to 12 weeks since her LNMP), but she is too sick to travel to the health centre, give her the treatment in Box 18.2. The risk from malaria to her life and the life of her fetus is greater than the risk from taking the medicine during early pregnancy. Send her to the health centre as soon as she is well enough to travel. Note that the drug Artesunate is given by slipping a specially shaped capsule — called a suppository — into the woman’s rectum by pushing it gently through her anus.

Box 18.2 Artemether injection and rectal Artesunate

Pre-referral intramuscular (IM) injection of Artemether is given in cases of severe suspected malaria. The dosage is 3.2 mg of Artemether for every kilogram (kg) of the woman’s body weight, in a single injection into the muscles of her upper arm.

Pre-referral rectal Artesunate given in suppositories with the following doses.

| Woman’s weight | Dose | Number of suppositories |

|---|---|---|

| 30-39 kg | 50 mg | 1 |

| over 40 kg | 400 mg | 4 |

Note that pregnant women are likely to weigh more than 40 kg after the first trimester.

The total number of malaria deaths and cases has been falling in Ethiopia in recent years, due to the major effort to prevent the disease and to treat it rapidly when it occurs. The Health Extension Programme is vitally important in reducing malaria even further, including early diagnosis and treatment of pregnant women coming to you for antenatal care.

18.1.4 Prevention of malaria

To prevent malaria, you must do everything possible to avoid mosquito bites. You should advise everyone in your community to act together to:

- Get rid of standing water where mosquitoes breed; drain pits that fill with rain water; cover or get rid of tin cans and pots that collect water near the house.

- Stay away from spending the night in wet places where mosquitoes breed.

- Use bed nets treated with insecticide, a mosquito-killing chemical. In many parts of Ethiopia you are able to distribute insecticide treated nets (ITNs; see Figure 18.4) to families who need them. These nets protect people who sleep under them from being bitten by mosquitoes, and they also reduce the risk to others sleeping in the same room because the insecticide repels mosquitoes from entering the house.

Preventing malaria should be an individual and a community responsibility. Consider holding a health campaign aimed at raising awareness of how to prevent malaria, using the health promotion techniques you learned about in Study Session 2 of this Module. Make sure the pregnant women you see for antenatal care know that they, their unborn baby and their children under 5 years are all at increased risk of malaria.

18.2 Anaemia in pregnancy

Women with anaemia have less strength for childbirth and are more likely to bleed heavily afterwards (postpartum haemorrhage), become ill after childbirth, or even die. You have already learned a lot about the diagnosis and prevention of anaemia in earlier study sessions in this Module, so in this session we will focus on its treatment and reinforcing what you have learned already.

What is anaemia and what happens in the body of an anaemic person?

When someone has anaemia, it usually means the person has not been able to eat enough foods containing iron. Red blood cells need iron to make haemoglobin, the substance that helps the red blood cells carry oxygen from the air we breathe to all parts of the body. A person with anaemia can’t make enough red blood cells, so their body is short of oxygen.

Note that some kinds of anaemia are caused by illness, not lack of iron, and some are inherited (genetic). It may also be caused by infestation with certain parasites, including malaria and hookworm. In this session we are concerned with anaemia caused by iron deficiency in the diet. Many pregnant women have anaemia, especially poor women who can’t afford to eat enough iron-rich foods, as you already know from Study Session 14.

18.2.1 Diagnosis of anaemia

Screen all pregnant women for anaemia at every antenatal visit, by asking about their symptoms. Useful questions to ask are:

- ‘Do you feel weak or get tired easily?’

- ‘Are you breathless (short of breath) when you do routine household work?’

- ‘Do you often feel dizzy, and have you ever fainted (become unconscious)?

These symptoms are caused by too little oxygen in the blood to provide energy for normal activities. A person with anaemia tends to feel short of breath because they have to breathe more rapidly to get enough oxygen into their body. If the brain can’t get enough oxygen, the person will feel dizzy and may faint.

The signs of anaemia (things a trained health professional can look out for or measure) are:

- Pallor: paleness inside eyelids, palms of the hands, fingernails and gums.

- Rapid breathing (faster than 40 breaths in a minute; normal breathing rate is 18-30 breaths per minute).

- Fast pulse (over 100 beats in a minute). You learned how to measure the pulse rate in Study Session 9 (Section 9.4).

On the first antenatal care visit

If you suspect that the woman may be anaemic, encourage her to have a blood test for anaemia if it is available at the nearest Health Centre. The blood test measures the concentration of haemoglobin (the iron-containing substance in the blood) to see if there is enough to carry the oxygen that she needs for normal activity and her unborn baby needs for growth. If blood testing is not available, use your judgement of the known signs and symptoms (listed above) to diagnose anaemia and offer treatment as described below.

On subsequent antenatal care visits

![]() If you are concerned that a pregnant woman has anaemia and she is not responding to the treatment you give her, you should refer her to a Health Centre straight away.

If you are concerned that a pregnant woman has anaemia and she is not responding to the treatment you give her, you should refer her to a Health Centre straight away.

- Look for pallor inside her eyelids, hands, fingernails and gums.

- Take her pulse. Is it over 100 beats per minute?

- Count the number of breaths she takes in 1 minute. Is it faster than 40 breaths?

Anaemia poses a serious risk to her health and that of her baby, especially around the time of delivery.

18.2.2 Prevention of anaemia in pregnancy

Eating a healthy diet

All pregnant women should be advised about eating enough foods containing good amounts of iron and folate (a vitamin, which is also called folic acid). You already know why she needs iron. Folate also helps to prevent anaemia in women who are pregnant or breastfeeding, and it can prevent some kinds of birth abnormalities in the baby.

Think back to Study Session 13. Name some foods that contain a lot of iron.

You may have thought of some of these: chicken; fish; sunflower, pumpkin and squash seeds; beans, peas and lentils; dark green leafy vegetables; yams; hard squash; red meat (especially liver, kidney and other organ meats); whole grain products such as brown bread; iron-fortified (enriched) bread; nuts and egg yolk.

Now name some foods that contain a lot of folate.

Fish; sunflower, pumpkin and squash seeds; beans and peas; dark green leafy vegetables; red meat (especially liver, kidney and other organ meats); brown rice; whole wheat; mushrooms and eggs.

Iron and folate tablets

You should give each pregnant woman enough iron tablets and folate tablets so she can take one tablet of each supplement once a day, or a combined tablet, until she sees you for the next antenatal visit. Make sure you give women more of these tablets at every visit. The preventive dosage is:

- Iron: 300 to 325 mg (milligrams) of ferrous sulphate once a day taken by mouth, preferably with a meal. Usually this dosage will be supplied in a single tablet combined with folate, but sometimes it can be given as iron drops.

- Folate: 400 µg (micrograms) of folic acid once a day taken by mouth, usually combined with iron.

18.2.3 Treatment of anaemia in pregnancy

If a woman has severe anaemia (a blood test shows she has haemoglobin less than 8 gm per litre of blood) in the 9th month of pregnancy, she should plan to have her baby in a hospital.

Moderate levels of anaemia can usually be cured by eating foods high in iron and folate, and also vitamin C (like citrus fruits and tomatoes), and by taking iron tablets and folate. The treatment dosage is:

- Iron: 300 to 325 mg (milligrams) of ferrous sulphate twice a day taken by mouth (double the dosage given to prevent anaemia).

- Folate: 400 µg (micrograms) of folic acid once a day by mouth (the same dosage as for prevention).

After prescribing these tablets and dietary advice, a pregnant woman with suspected anaemia should be checked again in 4 weeks. If she is not getting better, refer her to the health centre. She may have an illness, or she may just need a stronger iron supplement.

The supplements should be continued for 6 months during pregnancy if less than 40% of women in your community have anaemia. Continue for a further 3 months after the birth if more than 40% of women are anaemic, and your client is breastfeeding.

Side effects of iron tablets

Taking iron tablets can cause side-effects like constipation, nausea and black stools. Tell the woman she may have these side-effects, but it is important for her to keep taking the iron tablets. Taking the tablet when she eats a meal may help to prevent nausea, and drinking plenty of healthy fluids and eating lots of fruits and vegetables helps to prevent constipation. Reassure her that the black colour of her stools is not harmful and will go when it is safe for her to stop taking the iron tablets.

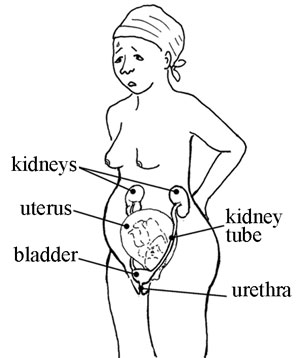

18.3 Urinary tract infections

The urinary tract (see Figure 18.5) includes the kidneys, kidney tubes, bladder and urethra (the opening where urine comes out of the body). They are all connected and work together to get rid of body wastes from the blood. First the kidneys clean the blood and turn waste into urine. Then the urine goes down the kidney tubes to the bladder. The urine stays in the bladder until the person urinates (passes water).

Urinary tract infection occurs when harmful germs (bacteria) get into the urethra. The infection can easily spread upwards to the bladder or kidneys. Doctors often refer to urinary tract infections as UTIs (when you say this it sounds like ‘you-tee-eyes’). You should assume that a UTI may involve all levels of the tract: the urethra, the bladder and the kidneys.

A woman is more likely to get UTIs during pregnancy than at other times. UTIs – particularly those that get all the way up to the kidneys – can be very dangerous for the mother and can also cause her to start labour too early if they are not treated right away. This is why it is important to check for signs of infection at every antenatal visit.

18.3.1 Prevention of UTIs

To prevent UTIs, teach women how to keep germs in their stools away from the urethra by wiping from front to back after urinating or passing stools (see Figure 18.6). If they wipe from the anus towards the urethra, they can carry germs into the genital area, where they could get into the urethra. Remind women and their partners to wash their hands and genitals before sex. Women should also urinate right after having sex. Using a condom also helps to prevent the spread of a UTI from a man to a woman.

In Section 18.3.3 (below) you will learn about giving antibiotics to women who have a history of frequent bladder infections to prevent the infection from coming back during pregnancy.

18.3.2 Diagnosing UTIs

A woman with a healthy urinary tract will not usually report pain, itching or burning when urinating. However, sometimes a woman has a UTI but she has no signs. It is important to try to tell whether the infection has reached the bladder, or if it has gone further up the urinary tract and reached the kidneys. Kidney infections are more serious and are a greater risk to the mother and her unborn baby.

Testing for UTIs

UTI can be detected by testing the woman’s urine. There are several different tests which are usually done at a Health Centre. There are dipsticks that change colour when dipped into infected urine, or the bacteria may be seen if the urine is looked at through a microscope, or the bacteria can be grown (cultured) in special containers until there are enough to identify them. All these tests require a clean ‘mid-stream’ urine sample.

You learned how to collect a mid-stream urine sample in Study Session 9. How would you explain to a woman how to do it?

You would tell her to begin urinating, but after she has produced the first trickle she should collect some urine from the middle of the stream in a clean container, and stop collecting before she empties her bladder.

![]() Itching or burning while urinating can also be a sign of vaginal infection or a sexually transmitted infection. If you see a patient with these symptoms, refer her to the nearest health facility.

Itching or burning while urinating can also be a sign of vaginal infection or a sexually transmitted infection. If you see a patient with these symptoms, refer her to the nearest health facility.

Dipstick, microscope and bacterial culture tests are the only certain way to diagnose a UTI, but they cannot tell the difference between infection of the bladder and kidney infections. You may be able to do this by careful questioning of the woman about her symptoms.

Symptoms of a bladder infection

Ask the pregnant woman if she experiences any of the following symptoms:

- Constant feeling of needing to urinate, even after having just urinated

- Pain or burning while urinating, or straight afterwards

- Pain in the lower belly, behind the front of the pelvis.

If you suspect a kidney infection, refer the mother immediately to the nearest health facility.

Symptoms of a kidney infection

Ask the pregnant woman if she experiences:

- Any signs of bladder infection

- Cloudy or bloody urine

- Fever, feeling very hot and sweating

- Feeling very sick or weak

- Flank pain (in one or both sides)

- Repeated vomiting

- Chills, rigors or shivering persistently.

Another symptom is pain in the lower back, sometimes on the sides (see Figure 18.7). But note that pain along the spine is common in pregnancy and may not be a sign of kidney infection. Normal back pain in pregnancy can be helped with massage, or exercise. If the pain is due to a kidney infection, massage or exercise won’t relieve it.

18.3.3 Treating a bladder infection

Encourage the mother to drink 1 large cup of clean and healthy liquid at least once every hour while she is awake. Liquids help wash infection out of the urinary tract. Water and fruit juices are especially good to drink. Encourage her to eat fruits that have a lot of vitamin C, like oranges, guavas (‘zeitun’) and mangoes.

If the infection does not start to improve quickly, or if the woman has any signs of kidney infection, refer her to the health centre, where tests can be performed to confirm the infection, and begin effective treatment with antibiotics (medicines that kill bacteria). The longer you wait to treat an infection, the more difficult it will be to cure.

If you have been trained to treat mild bladder infections with antibiotics, the dosage is:

- Amoxicillin: 500 mg (milligrams) by mouth three times per day for 5 days; this antibiotic may be supplied in tablets of 250 mg or 500 mg, so take care to give the correct number of tablets. Never give another antibiotic – only Amoxicillin.

Using antibiotics to prevent recurrent bladder infections

If the woman has had frequent urinary tract infections in the past, you can give her preventive treatment with antibiotics to prevent further infections during her pregnancy. The dosage is:

- Amoxicillin: 250 mg once a day at bedtime taken by mouth for the remainder of the pregnancy and for 2 weeks after the baby is born.

![]() If antibiotic treatment fails to cure the signs of infection, or if the woman gets another bladder infection later in the pregnancy, refer her to the Health Centre for urine tests. She may need treatment with a different antibiotic.

If antibiotic treatment fails to cure the signs of infection, or if the woman gets another bladder infection later in the pregnancy, refer her to the Health Centre for urine tests. She may need treatment with a different antibiotic.

18.4 In conclusion

Malaria, anaemia and UTIs are three of the most common medical disorders during pregnancy. In this study session you have learned how to diagnose, prevent and treat them. In the next three study sessions, you will learn about three more medical disorders that threaten the lives of pregnant women if they are not diagnosed and referred immediately: hypertensive disorders (Session 19), early pregnancy bleeding (Session 20) and late pregnancy bleeding (Session 21).

Summary of Study Session 18

In Study Session 18 you have learned that:

- Malaria is caused by a parasite that is spread by mosquitoes.

- A pregnant woman with malaria is more likely to have anaemia, miscarriage, early birth, small baby, stillbirth (baby born dead), or to die herself.

- It is important for pregnant women to avoid getting malaria — for example by using insecticide-treated bed nets — and to be treated quickly if they get sick.

- Malaria medicines may be costly and can have side-effects, but these medicines are much safer than actually getting sick with malaria, particularly during pregnancy. The usual anti-malaria medicine in Ethiopia is Coartem.

- Iron helps the blood carry oxygen from the air we breathe to all parts of the body. Too little iron in a pregnant woman’s diet means she will be short of breath because she is anaemic.

- Women with anaemia have less strength for childbirth and are more likely to bleed heavily, become ill after childbirth, or even die.

- Eating a diet rich in iron and folate, and taking these essential nutrients in tablets every day during pregnancy, can prevent anaemia from developing, and treat mild cases of anaemia.

- The urinary tract includes the kidneys, kidney tubes, bladder and urethra. UTIs are common during pregnancy and can be prevented by good hygiene.

- Bladder and kidney infections can be dangerous for the mother and can also cause her to start labour too early if they are not treated right away. Drinking a lot of clean liquids is often sufficient to flush the bacteria out of the body.

- Itching or burning while urinating is a common symptom of bladder infection; mild bladder infections can be treated with antibiotics. The usual antibiotic in Ethiopia at Health Post level is Amoxicillin.

- Kidney infection is paricularly dangerous and the woman should be referred immediately if she has cloudy or bloody urine, fever, and pain in the lower back.

Self-Assessment Questions (SAQs) for Study Session 18

Now that you have completed this study session, you can assess how well you have achieved its Learning Outcomes by answering these questions. Write your answers in your Study Diary and discuss them with your Tutor at the next Study Support Meeting. You can check your answers with the Notes on the Self-Assessment Questions at the end of this Module.

SAQ 18.1 (tests Learning Outcomes 18.1, 18.2 and 18.3)

Which of the following statements is false? In each case, explain what is incorrect.

A The risk of a UTI can be reduced by washing hands and genitals properly.

B A woman is more likely to get infections of the urethra, bladder or kidneys during pregnancy than at other times.

C It is important to give iron tablets to prevent anaemia only at the first antenatal visit.

D Encouraging a woman with a UTI to drink 1 glass of liquid every hour while she is awake helps to reduce her bladder infection.

E Malaria in pregnancy is associated with an increased risk of spontaneous abortion and stillbirth.

F Milk is rich in folate, so drinking plenty of milk during pregnancy can help to prevent anaemia.

Answer

A is true. The risk of urinary tract infection (UTI) can be reduced by washing hands and genitals properly.

B is true. A pregnant woman is more likely to get a UTI than when she is not pregnant.

C is false. Iron tablets to prevent anaemia should be given at every antenatal visit – not just the first one.

D is true. Encouraging a woman with a UTI to drink fluids every hour while she is awake will help to reduce her bladder infection.

E is true. Malaria in pregnancy is associated with an increased risk of spontaneous abortion and stillbirth.

F is false. Milk is good for pregnant women as part of a balanced diet, but it is not rich in folate; she should eat plenty of fish, beans, peas, dark green leafy vegetables, red meat, brown rice, whole wheat, mushrooms and eggs to increase the folate in her diet.

SAQ 18.2 (tests Learning Outcomes 18.1, 18.4, 18.5 and 18.6)

Complete the empty boxes in Table 18.1.

| Medical condition | Signs and symptoms |

|---|---|

| Malaria |

|

| Anaemia |

|

| Bladder infection |

|

| Kidney infection |

|

Answer

The completed version of Table 18.1 appears below.

| Medical condition | Signs and symptoms |

|---|---|

| Malaria | Chills, rigors, headache, weakness, fever alternating with chills, sweating as the temperature falls, sometimes diarrhoea/vomiting, muscle/joint pain. Malaria parasites detected by blood testing. |

| Anaemia | Pallor, rapid breathing (breathlessness), fast pulse (over 100 beats/minute), weakness, dizziness, occasionally fainting. Low haemoglobin detected by blood testing. |

| Bladder infection | Constant feeling of needing to urinate, pair or burning while urinating, pain in the lower belly. Bacteria detected by urine testing. |

| Kidney infection | As for bladder infection, plus cloudy or bloody urine, fever, feeling very sick or weak, flank pain in one or both sides which is not relieved by massage, repeated vomiting, chills and persistent shivering. |