Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Sunday, 23 November 2025, 1:48 AM

2. Understanding resilience

Introduction

In this section, I am going to cover the following topics:

- A brief overview of the co-operative movement and the challenges to resilience in the African context.

- A discussion of the concept of resilience: what do we really mean by it?

- A framework that can be used to analyse and understand co-operative resilience.

If you chose to look at Borda-Rodriguez and Vicari’s paper in Activity 1, you will have some preparation for what follows – but there is no problem if you did not to look at that paper.

2.1 Resilience in the African co-operative movement

Many co-operatives in Africa were initiated under colonialism at the beginning of the twentieth century. For a long time, including after independence or liberation, they were mainly controlled by the state and subject to top-down controls. This control was relaxed during economic liberalisation in the 1980s and 1990s. However, because co-operatives had been reliant on state intervention and support, many were weakened or collapsed. Co-operatives with strong market niches – such as some agricultural products or dairy – were more likely to survive.

However, this process, along with the need for livelihood opportunities in difficult economic circumstances, has encouraged a different kind of co-operative movement to grow in many countries. There are debates and different data about the extent and strength of this growth, and especially about how many co-operatives are active and viable (Develtere et al., 2008; Pollet, 2009; Chambo et al., n.d.). However Develtere et al. have characterised this growth as a ‘renaissance’ of the African co-operative movement, with a shift towards the kind of co-operatives aspired to in the International Co-operative Alliance’s values and principles, and a move away from some of the practices that had grown up in the past.

Growth of the movement seems to focus primarily on the agricultural (and livestock/dairy) sector and on savings and credit co-operatives. There are many challenges, not least:

- the legislative frameworks needed to enable co-operatives to have a clear environment in which to operate

- skills in management and the type of governance that co-operatives require

- the need for an inclusive membership that enables women and youth as well as men to become members and participate, and

- the need to capitalise the co-operatives through members buying shares.

In addition, of course, is the need for good links to markets, ability to negotiate deals and the potential for adding value to producer output.

In some countries, such as Uganda, new models of co-operative organisation have sprung up, and it’s worth looking at some of the features in Uganda to start a deeper exploration of what resilience might mean. You can do so by going to Box 1 in Activity 2 which is an extract from the working paper by Borda-Rodriguez and Vicari (2013a, pp. 9-10).

2.1.1 Innovating for resilience in the Ugandan co-operative movement

Activity 2 Innovating for resilience in the Ugandan co-operative movement

Read Box 1 and try to identify what aspects of the current developments in the Ugandan co-operative movement will reinforce co-operative resilience.

Discussion

The aspects that I thought would be conducive to resilience were:

- organisational efficiencies

- diversification of products

- linking production to credit provision with a clear repayment system

- linking in to new domestic markets

- bringing co-operatives together to supply such markets

- paying attention to member inclusion (including women and youth) and member education

- making the leadership accountable

- developing a good relationship with, but independent from, government.

However, what is meant by resilience, and why did I identify those particular features?Box 1 The development of the Ugandan co-operative movement

The Ugandan Co-operative Alliance [UCA - the national federation] has developed and implemented an innovative approach to building networks among co-operatives, called Area Co-operative Enterprises (ACEs). ACEs work as smaller co-operative unions, with lean management structures, encompassing fewer primary co-operatives, and being strongly rooted at grassroots level (Kwapong and Korugyendo, 2010). They do their business differently compared to traditional co-operative unions, bulking instead of buying from members, working for commission (which is agreed upon in advance) and not taking ownership of the commodity.

This new network approach has been developed with the purpose of ensuring that co-operative structures are efficient, not debt-ridden, deliver more services and bring maximum benefits to their members while at the same time ensuring that co-operative organisations can earn enough income to sustain their operations. However, this also means that most of the risk is borne by the farmer. That is why UCA encourages ACEs to bulk and market at least three products, which in turn encourages farmers to diversify, reducing risks from crop failure or market price volatility (Kwapong and Koruyendo, 2010; UK Co-operative College, 2011).

Another interesting innovation is about the so-called ‘tripartite system’. As explained by Kwapong and Koruyendo (2010), primary co-operatives, ACEs and SACCOs are interconnected, with the latter providing financial assistance to farmers and to the ACEs. Specifically, as reported by UK Co-operative College (2011), SACCOs provide a loan to the farmer of approximately 50% of the estimated price of the crop bulked in the ACE’s warehouse. Once the crop is sold, the farmer is required to pay off the SACCO first and thus can keep the remainder.

The UCA Report (2012) and Msemakweli (2012a, 2012b) explain that the ‘tripartite system’ is just a part of a broader strategy. Efforts are devoted to find new opportunities in trade liberalisation, particularly about the emerging domestic market for food commodities. Promotion of co-operation among co-operatives is another strategic issue, with co-operatives encouraged to come together, for instance, to share contracts which they would not be able to fulfill as individual co-operatives. UCA also promotes partnerships between co-operatives and other private sector players, creating business and credit opportunities respectively with buyers and banks.

UCA is also promoting a participatory movement, acknowledging the fact that a crucial feature for co-operatives to succeed involves members participating actively, including contributing adequate capital to carry out the business, making good policies, holding the leadership accountable and using the power of the vote to remove them if they do not perform, doing the business through their co-operative and receiving member education.

Through education UCA aims to spread and develop an environment able to bring about leaders with vision, commitment, and a good record in their respective communities and appropriate skills to run successful co-operative businesses. UCA also regards women and youth as key players in the development of the current co-operative movement in the country.

Finally, as part of its work, UCA lobbies the government in order to foster a conducive environment that enables the growth of co-operatives as autonomous, self-financing and self-reliant enterprises. Such efforts are visible in the National Co-operative Policy of 2011, whereby the government provides the policy guidelines for co-operative development in Uganda, aimed at enabling co-operatives to play a leading role in poverty alleviation, employment creation and social-economic transformation of the country. UCA has also made clear to national and international organisations that it is committed to defending co-operatives from any interference, acknowledging that their independence from the state is a major factor for their sustainability.

2.2 What is meant by resilience?

We all have a common sense conception of resilience. However, there is debate about it as a concept, as well as about what constitutes resilience when it comes to co-operatives.

Activity 3 Defining resilience

Before continuing, you might jot down what you think the general characteristics of resilience are, and what they might be in the case of co-operatives. Then review your notes in the light of the following discussion.

Discussion

Borda-Rodriguez and Vicari (2013a) carried out a review of literature on resilience, which you may be familiar with now. They identified the following characteristics:

- The capacity to absorb stresses and shocks and maintain core functions.

- The ability to adapt to new situations (sometimes called ‘adaptive capacity’), although it is pointed out that adapting in one situation or context might lead to stresses and strains in another part of an organisation or network or location.

- Anticipating what might be coming – looking and planning ahead.

- Seizing opportunities and putting oneself or one’s organisation at an advantage (which suggests that people and organisations need to have access to information about what’s possible).

- Being able to cope with risk and uncertainty.

- Linked to this point, reducing vulnerability and enhancing capabilities.

Here is it worth quoting the working paper directly. Take a few moments to absorb and reflect on the following paragraph:

The potential to adapt is better understood in the light of the capability approach developed by Sen (1999) who defines development as the expansion of people’s freedom and capabilities and their freedom to ‘lead the kind of lives they value and have reason to value’ (ibid: p. 18). Here this potential to deal with uncertainty can be conceptualised as the capability to face risks and insecurity. This capability depends in turn on the conversion of people’s endowments (monetary, capital, physical, human and social ones) through their entitlements to call on these resources (Adger and Kelly, 1999) and social opportunities (i.e. participation in the market, public policy and civil society) (Lallau, 2008) as well as on the whole spectrum of human capabilities enjoyed by people, such as education and healthcare (Burchi and De Muro, 2012).

With this discussion in mind, what then is meant by co-operative resilience?

2.3 What is meant by co-operative resilience?

Borda-Rodriguez and Vicari note in particular that the capabilities outlined in the previous section depend on the agency that people have either as individuals or collectively in groups, communities and organisations. So in this sense, an organisation needs to have the capabilities described for individuals in Section 2.2.

Without going through their discussion, which you can do for yourself if you want to go into more depth, they conclude that a resilient organisation has the ‘ability to develop a set of dynamic capabilities that enable it to’:

- adjust to shocks

- moderate the effects of and cope with the consequences of risks

- take advantage of opportunities emerging from a crisis

- develop internal and external organisational skills

- implement learning and innovation processes, which strengthen the organisational ability to deal with changing environments

- satisfy the majority of internal and external stakeholders.

Co-operatives of course have particular characteristics and requirements as organisations. They are steered by particular values and principles, they are member-owned, they are democratically controlled, and they have to survive (and hopefully prosper) in a (usually) competitive business environment.

So in order to satisfy the dynamic capabilities outlined above, what do they have to do?

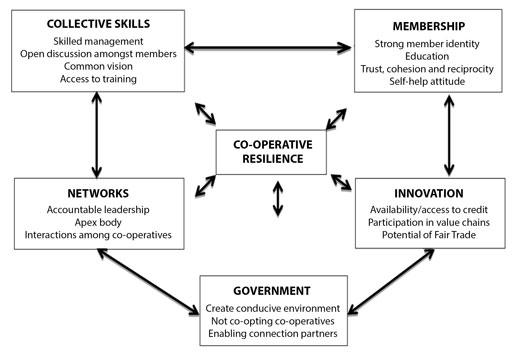

Borda-Rodriguez and Vicari (2013b, p. 4) suggest the framework in Figure 1 for analysing whether and how co-operatives are resilient or not. The framework is based on reviewing the literature about some of the fundamental challenges faced by co-operatives, particularly, but not only, in a developing country context.

I will look at each component in turn.

2.3.1 Membership

‘Co-operatives are good as their members make them’ (Münkner, 2012, p.16).

There are many challenging issues in relationship to the membership of co-operatives:

- what motivates people to become members

- what benefits they derive or perceive from their membership

- what world views and convictions they come to the co-operative with

- their understanding of what it means to be a member of a co-operative and knowledge of the values and principles of co-operation

- the extent to which members are homogeneous – i.e. from the same community or same type of work – or heterogeneous with mixed backgrounds and concerns

- gender and age equity and inclusion and a supportive legal framework for this to happen

- the extent to which members participate in the governance of the co-operative and identify with the co-operative and as co-operators

- their individual knowledge, experience and expertise

- the amount they are able to offer in terms of investing in the co-operative through buying shares

- the relationship between co-operative members – whether there is trust and unity or conflict.

The relationships between members that enable them to become a resilient unit is sometimes called ‘social capital’. There is considerable debate about this concept, for example: Is social capital really capital in the true sense? Can social capital be mobilised for negative or anti-social purposes rather than positive collective gain?

So the important dimension is to know about the quality of the relationships between members and how they are able to promote resilience in the co-operative. An unhappy or dysfunctional membership might not be resilient at all.

2.3.2 Collective skills

It’s tempting to think that collective skills concern education and training. Access to education and training for co-operatives and their members can certainly be a factor in their resilience. However an important dimension for collective skills in a co-operative setting is the working relationships – between members, and between members and officers/board.

To take this further, there is quite an interesting literature developing around co-operative learning: the way members of co-operatives learn from each other because of their association with each other. Ian MacPherson, a well-known academic in the Canadian co-operative movement, has called this process ‘associative intelligence’ (MacPherson, 2003). Other researchers (Facer et al., 2011) have called it ‘learning through co-operation’. Hartley (2012) undertook an extensive study of how youth co-operators in Uganda and Lesotho learnt new knowledge, skills and gained confidence through co-operative activities and co-operative networks. She argued that co-operatives and their networks act as ‘expanded learning spaces’, where ‘social’ learning – learning that is not simply individual but is embedded in groups and organisations – takes place.

Collective skills, whether gained through the process of co-operation outlined above, or through education and training, are important for co-operative resilience in a number of ways:

- in reinforcing the ability to carry out the particular forms of governance required by co-operatives

- being able to discuss and manage complex issues

- sustaining and supporting relationships between members

- reinforcing co-operator identities

- being able to carry out responsibilities needed by the co-operative, such as record-keeping, keeping accounts, managing products, money and so on.

In this respect, the networks that a co-operative and its union have may be very important for some of the formal training for resilience, as well as the processes of social learning that take place more informally. In a developing country context, such networks will be particularly important and might include Fair Trade buyers as well as development agencies, co-operative colleges and the government.

2.3.3 Networks

Co-operative connections and networks are all an important part of resilience. Such networks may be with their communities, to other co-operatives providing similar products or services or those that carry out complementary activities (as in the Ugandan example), to different markets and buyers, to local authorities or government.

While relationships between members are sometimes called ‘bonding’ social capital, relationships with people and organisations in a wider network are sometimes called ‘bridging’ social capital. Again these terms are disputed but you might come across them being used in this way in your work in, or with, co-operatives.

Co-operatives may have horizontal networks with other similar co-operatives, which enable them to enhance their collective bargaining power in the market or collaborative in product and service provision (potentially also reducing costs per unit through increasing economies of scale). However, as noted in the paper by Borda-Rodriguez and Vicari (2013a), some co-operatives that are internally very cohesive may not want to bridge to co-operatives that have weaker internal ties (Simmons and Birchall, 2008).

Co-operatives may also be part of vertical structures, such as unions or federations, which are able to provide them with services they need: education and training, links to other networks, perhaps seeking funding for programmes of co-operative development, lobbying government for improved legislation, and so on.

Finally, resilience can be enhanced by the extent to which co-operatives have even wider, international networks, for example to companies or organisations that wish to buy their products or make use of their services. In addition wider networks might be useful sources of knowledge, information and training and/or promote knowledge-sharing activities.

An important aspect for any individual co-operative is to have diverse networks, as dependence on one link for, say, marketing outputs, might result in vulnerability if that link falls down or reduces its prices.

2.3.4 Innovation

There are various definitions of innovation, depending on what aspect of an organisation’s life the process of innovation concerns. In another paper by Borda-Rodriguez and Vicari (2013b, p. 3), they note:

... all definitions are rooted in the assumption that innovation at its most essential level is the application of all types of knowledge that enable an organisation, institution or individual to improve their technological and economic performance.

In the context of co-operatives, innovation might involve a range of dimensions from changing technologies to changes in how the co-operative is organised (including who is included). It might also involve changes in capacities and capabilities of the co-operative through education, training and social learning. It might also involve changes in products produced by the co-operative or in the processes of production, or it might involve developing new market niches.

Many aspects of the production side of co-operatives are influenced by the value chains they are part of. Value chains may be local to the co-operative but are likely to be increasingly global or to have global elements (for example, inputs that are needed for production).

Value chain refers to the processes and linkages from inputs to final consumption. The processes might involve horizontal linkages (for example, the interactions between co-operatives that are producing a similar product, such as coffee, and are part of a union of such co-operatives). They might involve vertical linkages, for example between suppliers of inputs for coffee production and the members of a co-operative. An important dimension is who controls or ‘governs’ each aspect of the chain, and who benefits from it.

Innovations to improve technological and economic performance within value chains are seen as ‘upgrading’ (Kaplinsky and Morris, 2001). Upgrading may take the forms of:

- Process upgrading: innovating in production processes to increase efficiencies (for example, by technology changes or improved techniques of production).

- Product upgrading: improving products or producing new products in the co-operative (for example, as you will see later in this unit, producing better quality coffee or different types of timber for different uses).

- Functional upgrading: adding value by changing the activities that a co-operative engages in (for example, a sawn timber co-operative might start designing the doors that the timber is used for).

- Chain upgrading: engaging with a new value chain (for example, a agricultural product in the case of agricultural cooperatives or proving insurance as well as credit in SACCOs).

Being able to undertake such upgrading requires investment. Access to finance (credit) for co-operatives and their members is a fundamental prerequisite. This is often a challenge, most particularly in developing countries where co-operatives are not always able to access credit from commercial banks. Again, the Ugandan co-operative movement presents an example of how credit can be made available by linking production and marketing co-operatives with SACCOs. Favourable deals can also be made with buyers, particularly, for example, with FairTrade companies. However changes to standards are often involved, as you will see in one of the case studies in Section 3.

2.3.5 The role of government

The relationship between co-operative unions and federations and governments can be very important for co-operatives governance, independence of action and ability to innovate and meet new demands and market challenges. The history of state control in many developing and transitional countries has often undermined co-operative principles and the ability to create viable independent businesses.

Resilience is not about divorcing co-operatives from government but rather for government to create a ‘conducive environment’ (Münkner, 2012) for co-operative activity. A conducive environment includes (ibid, p. 44):

- An economic, political and legal system, which recognises co-operatives as autonomous private member-owned forms of business.

- A co-operative development policy, drawn up in the spirit of UN Guidelines ILO recommendations for co-operatives (2001 and 2002 respectively).

- Infrastructure that can facilitate co-operative activities, from communications to logistics, information and extension services.

However, as noted by Borda-Rodriguez and Vicari (2013a, p. 37):

The relationship between governments and co-operatives is a dynamic process, highly dependent on the economic and political context, on the strength of the co-operative representative organisations and on the ability of membership to influence how networks function.

In the light of considering this framework for resilience, I want you now to carry out Activity 4 and spend a bit of time consolidating and reflecting on your understanding.

2.4 Reflecting on the resilience framework

Activity 4 The resilience framework

Using the resilience framework of membership, collective skills, networks, innovation and role of government, think about a co-operative familiar to you (wherever in the world).

Make notes on what you know about this co-operative with respect to the different dimensions of the framework. What do you think your notes tell you about the resilience of the co-operative?

You can now go back to any of the resources you were not able to look at in Activity 1 and review them.

Alternatively you might like to look at a short paper from the ILO on co-operatives and value chains:

ILO (2012) ‘The role of co-operatives and business associations in value chain development’, Value Chain Briefing Paper 2, ILO.

This briefing paper can be found by going to Enterprises Department, or just search for the publication on the ILO website.

In the ILO Enterprises Department, you will also find many other publications and materials on co-operatives.

Box 1 The development of the Ugandan co-operative movement

The Ugandan Co-operative Alliance [UCA - the national federation] has developed and implemented an innovative approach to building networks among co-operatives, called Area Co-operative Enterprises (ACEs). ACEs work as smaller co-operative unions, with lean management structures, encompassing fewer primary co-operatives, and being strongly rooted at grassroots level (Kwapong and Korugyendo, 2010). They do their business differently compared to traditional co-operative unions, bulking instead of buying from members, working for commission (which is agreed upon in advance) and not taking ownership of the commodity.

This new network approach has been developed with the purpose of ensuring that co-operative structures are efficient, not debt-ridden, deliver more services and bring maximum benefits to their members while at the same time ensuring that co-operative organisations can earn enough income to sustain their operations. However, this also means that most of the risk is borne by the farmer. That is why UCA encourages ACEs to bulk and market at least three products, which in turn encourages farmers to diversify, reducing risks from crop failure or market price volatility (Kwapong and Koruyendo, 2010; UK Co-operative College, 2011).

Another interesting innovation is about the so-called ‘tripartite system’. As explained by Kwapong and Koruyendo (2010), primary co-operatives, ACEs and SACCOs are interconnected, with the latter providing financial assistance to farmers and to the ACEs. Specifically, as reported by UK Co-operative College (2011), SACCOs provide a loan to the farmer of approximately 50% of the estimated price of the crop bulked in the ACE’s warehouse. Once the crop is sold, the farmer is required to pay off the SACCO first and thus can keep the remainder.

The UCA Report (2012) and Msemakweli (2012a, 2012b) explain that the ‘tripartite system’ is just a part of a broader strategy. Efforts are devoted to find new opportunities in trade liberalisation, particularly about the emerging domestic market for food commodities. Promotion of co-operation among co-operatives is another strategic issue, with co-operatives encouraged to come together, for instance, to share contracts which they would not be able to fulfill as individual co-operatives. UCA also promotes partnerships between co-operatives and other private sector players, creating business and credit opportunities respectively with buyers and banks.

UCA is also promoting a participatory movement, acknowledging the fact that a crucial feature for co-operatives to succeed involves members participating actively, including contributing adequate capital to carry out the business, making good policies, holding the leadership accountable and using the power of the vote to remove them if they do not perform, doing the business through their co-operative and receiving member education.

Through education UCA aims to spread and develop an environment able to bring about leaders with vision, commitment, and a good record in their respective communities and appropriate skills to run successful co-operative businesses. UCA also regards women and youth as key players in the development of the current co-operative movement in the country.

Finally, as part of its work, UCA lobbies the government in order to foster a conducive environment that enables the growth of co-operatives as autonomous, self-financing and self-reliant enterprises. Such efforts are visible in the National Co-operative Policy of 2011, whereby the government provides the policy guidelines for co-operative development in Uganda, aimed at enabling co-operatives to play a leading role in poverty alleviation, employment creation and social-economic transformation of the country. UCA has also made clear to national and international organisations that it is committed to defending co-operatives from any interference, acknowledging that their independence from the state is a major factor for their sustainability.