Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Thursday, 22 January 2026, 2:31 AM

Immunization Module: Immunization Programme Management

Study Session 8 Immunization Programme Management

Introduction

For more details of health planning, see Study Sessions 12 to 16 of the Health Education, Advocacy and Community Mobilisation Module, Part 2.

This study session is on the effective management of the immunization programme in your catchment area. We will show you how to plan, implement, monitor and evaluate your immunization activities, with the overall goal of increasing the immunization coverage rate in your community and sustaining the increase over time. First, you will learn how to prepare an annual plan of the immunization programme for your Health Post and measure progress towards meeting your objectives. Then, we show you how to prepare for your actual immunization sessions, either in a fixed facility (such as your Health Post), or in outreach activities or mobile delivery teams. You have already learned how to calculate the resources you will need in Study Session 5, and you may need to refer back to those calculations as you read this study session.

Learning Outcomes for Study Session 8

When you have studied this session, you should be able to:

- 8.1 Define and use correctly all of the key words printed in bold. (SAQs 8.1, 8.2 and 8.3)

- 8.2 Describe the principles and concepts of planning an efficient immunization programme, and summarise the six steps in the planning process. (SAQs 8.1, 8.2 and 8.3)

- 8.3 List some common indicators of progress in monitoring and evaluating an immunization programme. (SAQ 8.3)

- 8.4 Explain how you would determine the immunization eligibility of an infant or woman who does not have an immunization record card. (SAQs 8.3 and 8.4)

- 8.5 Describe how to set up before an immunization session and what you should do after it has ended. (SAQs 8.4 and 8.5)

- 8.6 Describe how an immunization session should be managed at a fixed site, an outreach site and a mobile delivery service. (SAQ 8.5)

8.1 Planning your immunization programme

For any activity to improve the health and wellbeing of your community, you need to have a plan. It is often said that if you fail to plan, you plan to fail. As a Health Extension Practitioner you will be expected to develop an annual immunization action plan that can reach all the children and women in your catchment area. Thus, careful planning is an important activity that every Health Extension Practitioner must undertake.

8.1.1 Collecting basic information about the community

Before you can begin to make an effective plan for any health intervention, you must first collect some basic information about the community you serve. For example:

- The size of the total population of your kebele, and the size of the target population — in this case, clients for immunization.

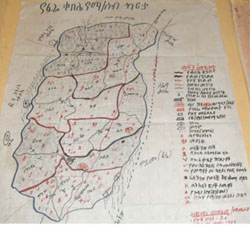

- A map of your kebele showing the location of homes, health facilities and other buildings, and geographical features such as paths, ponds, rivers or forests. (Figure 8.1)

- The distances (in kilometres, or travel time by walking) between the health centre and your Health Post, and between the Health Post and the furthest members of the community (Figure 8.2).

- Details of transport and communication networks in the area, e.g. roads, and the availability of telephone, radio or TV coverage.

- Knowledge of available energy sources in the area, e.g. electricity generators and supplies of gas, diesel or kerosene.

- The location of potential partners who could assist you, e.g. community associations, employers, private institutions, charitable organisations, etc.

Information like this will help you to anticipate possible problems that could affect your planned activities. Information such as the geography, socioeconomic situation and the health profile of the community you are working in will help you to establish the current situation and work out what problems or challenges are to be expected. If you can identify the possible problems and their causes and their effects in advance, then you may be able to work out potential solutions before the problem becomes serious.

8.1.2 Steps in the planning process

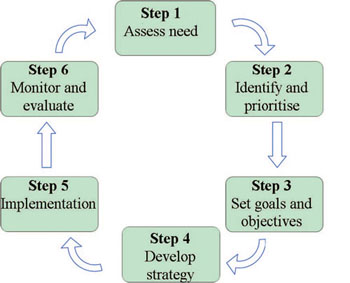

When you know a lot about your community, you can begin to make a plan of action. The planning process should follow the six steps outlined in Figure 8.3. We have briefly summarised each step in Box 8.1, and in the rest of this section we will look at each of them in more detail.

Box 8.1 Steps in the health planning process

Step 1 Assess need: identify the problems and clarify the situation you want to improve.

Step 2 Identify and prioritise: select your priorities for action — what are the most important issues to tackle?

Step 3 Set goals and objectives: what is the overall goal of your activities, what are your specific objectives (targets) and in what timescale do you aim to achieve them?

Step 4 Develop strategy: What is your action plan? What activities, resources (people, equipment) and finances will be needed to achieve your objectives? How will you explain your action plan and gain community support for it?

Step 5 Implementation: How will you deliver your plan? Do you have everything you need to make it successful?

Step 6 Monitor and evaluate: What data will you collect and how will you evaluate the impact and outcomes of your activities? How will you measure progress towards meeting your objectives? Notice that in Figure 8.3, the results of Step 6 help you improve the next cycle of planning, beginning at Step 1.

Resource Management at Health Post level is covered in detail in the Health Management, Ethics and Research Module.

8.1.3 Immunization needs assessment

A health needs assessment is the process of identifying and understanding the health needs of your community. It includes identifying any problems and their possible causes that make it harder to meet those needs. In relation to immunization, the key questions that you need to address are:

- Has the immunization coverage rate reached the targets that were planned in the previous year? If not, what were the problems?

- If there were outbreaks of vaccine-preventable diseases in your kebele, what does this imply about the effectiveness of your immunization service? For example, has it been difficult for people to get to the Health Post or attend outreach events?

- Have there been many defaulters — clients who began a series of routine immunizations but ‘dropped out’ before the EPI schedule was completed? What are the possible reasons for dropouts?

Make a list of possible problems that might need to be addressed in your community if your goal is to increase the immunization coverage rates.

You may have thought of other problems in addition to those below:

- The target population is large and very widespread; people who live a long way from the Health Post find it difficult to get to immunization sessions

- The roads to the Health Post are flooded in the rainy season

- Immunization is only available on certain days; some people cannot attend on those days

- Communicating about immunization sessions is difficult; some people come on days when immunization is not available

- Vaccine supplies are sometimes not enough to immunize all the children and mothers who come

- The refrigerator is unreliable and vaccines have to be moved to the health centre for safety

- There is a high dropout rate, possibly because a child had a severe allergic reaction after an immunization last year, and negative rumours spread; some parents refused to bring children for immunization.

If you have identified problems that contribute to low immunization coverage rates in your area, discuss them with your supervisor and local health officials, and make a list of possible solutions. For example, if the problem is low immunization coverage, then the solution might be one (or more) of those listed in Box 8.2.

Box 8.2 Some ways to address low immunization coverage rates

- Improved communication with the local community about the huge benefits and very low risks of immunization

- More in-service training, updating or supportive supervision for you and other health workers, including community volunteers

- Mobilisation of additional people, equipment, finances or other resources to improve delivery of the immunization programme

- Change of immunization strategy, e.g. increased use of outreach or local immunization days

- Focus group discussions with community members to find out why immunization coverage is low

- Regular review meetings with kebele leaders and local health officials to assess progress

- Partnerships with other organisations (e.g. community associations, charities, private sector) to assist in delivering the programme.

Remember that some solutions may not be appropriate to your setting, or may not be feasible in your kebele. For example, additional in-service training may not be affordable in the short term, or there may not be a suitable local organisation willing to assist with your immunization activities.

8.1.4 Identify and prioritise problems

Prioritisation is the process of informed decision-making about what to do first, second, third and so on, when there are competing claims on human and other resources. It is impossible to solve all problems at once because there are always many resource constraints. In order to select your priority activities — in this case, with the aim of reducing vaccine-preventable diseases through delivery of an effective immunization programme — you should consider the criteria below for each of the problems you have identified:

- magnitude of the problem — what percentage of the population is at high risk of developing the disease, or is already affected by it?

- severity of the problem — how serious is the disease in question, in terms of its impact on health and the risk of death?

- socioeconomic impact of solving the problem — how will the social and economic circumstances of individuals, families and the community benefit if immunization coverage increases?

- feasibility of tackling the problem — do solutions exist, and is it realistic to increase immunization coverage with the available technical resources, personnel and organisational capabilities?

- affordability of tackling the problem — is the financial support adequate for an improved immunization programme?

- acceptability to the beneficiaries of tackling the problem in the ways suggested — does it meet community and government concerns?

Consider two diseases: pneumonia and the common cold. Which of these has the greatest magnitude and which has the greatest severity?

The number of people who suffer from a common cold is much higher than the number with pneumonia, but pneumonia is a much more serious disease than the common cold. So the magnitude of the problem is greater for the common cold, but the severity of the problem is greater for pneumonia.

A simple scoring chart, like the one in Table 8.1, can help you to rank priorities for each of the health problems identified in your needs assessment. For each problem, you decide on a score from 1 to 5 for each column, where:

- 1 = concern about this criterion is very low

- 5 = concern about this criterion is very high.

| Problem | Magnitude | Severity | Impact | Feasibility | Affordability | Acceptability | Total score | Rank |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neonatal tetanus | ||||||||

| Measles |

In the example in Table 8.1, neonatal tetanus and measles are listed as health problems that can be reduced by immunization. How would you score each of these conditions based on your knowledge of these diseases and their impact in your community?

We can’t guess what scores you wrote in Table 8.1, because local circumstances will vary in different communities. But you should have given a lower ‘magnitude’ score and a higher ‘severity’ score to neonatal tetanus than you did to measles. More children suffer from measles than tetanus, and measles kills a higher number of children than any other vaccine-preventable disease worldwide (higher magnitude). But the majority of children infected with measles recover, whereas over 70% of babies with neonatal tetanus will die (higher severity). To take another example, you may have decided that the feasibility of vaccinating children once against measles is greater than the feasibility of vaccinating pregnant women, and all women of childbearing age at least twice (preferably three to five times) with tetanus toxoid.

When you have given a score to each problem in your priority chart, you add up the scores and enter this figure in the ‘Total score’ column. You then assign a rank to each problem according to its total score. The highest scoring problem has a rank of 1; the next highest scoring problem has a rank of 2, etc. Conducting an assessment like this will help to clarify your thinking about which problems to tackle first. This will also enable you to explain the reasons for your priorities to community members, so they understand why you have prioritised certain activities.

8.1.5 Setting goals and objectives

Once you have identified problems with feasible solutions and ranked your priorities, then you must set clear objectives (or targets) for each problem in your priority list in order to make progress towards your overall goal. In this case, the goal is to increase the immunization coverage rate in your community. The objectives for delivering your goal must be specific and measurable, and state exactly what you want to achieve, where the activities will take place, which target group will be addressed and when the target should be achieved. For example, some possible objectives of an improved immunization programme might be:

- To reach 95% coverage of all eligible children in the catchment area with the third dose of pentavalent vaccine (Penta3) by the end of the year.

- To conduct immunization sessions at the Health Post twice every week for 48 weeks of the year.

- To update the registration of newborns in your catchment area once a month for the whole year.

What objective could you set for tetanus toxoid (TT) coverage?

You may have thought of other objectives, but one might be to increase by 20% the number of women of childbearing age who receive more than two doses of TT this year (Figure 8.4).

Notice that in all the examples above, a timescale is given for achieving the objective, and the outcome (success or failure to meet the objective) can easily be measured if accurate records are kept. Record keeping is covered in Study Session 10.

8.1.6 Developing strategies and activities in your action plan

After agreeing your objectives, the next task is to decide on the strategies and activities for achieving them. This means working out the methods you will use and the activities you will undertake, and writing a clearly stated action plan. The action plan should include every activity to be performed during the year, the time when that activity is to be done, who will do it, how that person (or people) will do it, and what resources will be needed. In developing your action plan, you should ensure that your strategy and activities are relevant to resolving the identified problems, and that they are technically feasible, financially affordable and acceptable to the community.

What activities might you undertake in order to meet the objective of updating registration of newborns in your community every month?

Here are some suggestions. You may have thought of others.

- Ask about recent births in each family whenever you visit a household for any reason.

- Ask kebele leaders, traditional birth attendants and other influential people what recent births have occurred in each village.

- Ask each mother who visits the Health Post when she (or any other women in her family) last had a baby, and check that you have recorded the birth.

8.1.7 Estimating resource needs

You have already learnt how to estimate the size of your target population and your resource needs in Study Session 5.

Your action plan should also include an estimate of your resource needs. Resources include people, materials, time, finance and information, and these should be determined in advance for each of the planned activities. The first and most important estimate is the total size of the population and the number in the target population for your activities.

What is the target population for the Expanded Programme on Immunization (EPI)?

It is the number of children aged 0–11 months and women of childbearing age (15–49 years).

You can then determine the resources required (vaccines, diluents, infection equipment, etc.) for delivering an effective immunization programme for this target population. The next step in the action plan is to allocate people (e.g. community volunteers), materials, time and finance to each of the activities in your plan.

8.1.8 Implementing your action plan and maintaining community support

Community communication about immunization is described in more detail in Study Session 9.

Once the action plan for the year is complete, it should be communicated to all stakeholders at community level, your supervisor and the woreda health office. You should arrange a meeting with local government administration officials, community leaders and community volunteers to discuss your plan and gain their approval and support (Figure 8.5). Once approved, it is your responsibility to implement the plan. You have to keep all stakeholders well informed about progress during the year, so that you can agree on a solution to any problems you encounter during the implementation period.

8.1.9 Monitoring and evaluation indicators

Monitoring and evaluation are crucially important parts of any health plan. Monitoring refers to the continuous observation and collection of relevant data, and evaluation means analysing the data to see if you are meeting your objectives. Therefore, you need to select reliable indicators of progress for each of the objectives in your action plan. Collecting and analysing data from these indicators is an essential activity during the implementation of your immunization programme.

Indicators of progress in immunization programmes

Some of the main EPI indicators of progress that are commonly used to monitor and evaluate immunization programmes are given below:

- Immunization coverage rate for each vaccine, i.e. the percentage of all eligible children who have received all doses of a vaccine under one year of age, according to the EPI schedule.

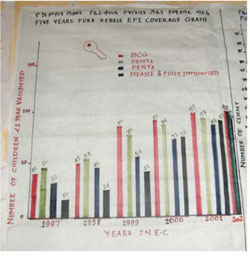

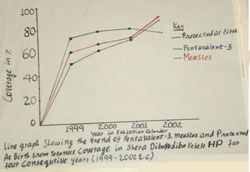

- Percentage of fully immunized children aged under one year, who have received all recommended doses of all vaccines (including measles vaccine at age 9 to 11 months), according to the EPI schedule (Figure 8.6).

Years in Figure 8.6 are given in the Ethiopian calendar (E.C.), and correspond to 2005–2010 in the European calendar.

- Percentage of pregnant women with adequate TT doses, defined as receiving any of TT3, TT4 or TT5. This indicator is often abbreviated to TT2+ (because more than two doses of TT vaccine have been given).

- Percentage of children protected at birth (PAB) from neonatal tetanus, because their mother received a valid dose of TT2+ vaccination at least two weeks before delivery (Figure 8.7).

- Dropout rates: the percentage of children and mothers not completing all the scheduled EPI immunizations.

- Reported new cases in the community of:

- neonatal tetanus

- acute flaccid paralysis (AFP)

- measles in children under five years of age

- all vaccine-preventable diseases.

- Number of reports of adverse events following immunization (AEFIs).

- Vaccine wastage factors

- Reporting completeness, accuracy and timeliness.

You learned how to calculate vaccine wastage factors in Study Session 5. Monitoring and reporting procedures are taught in Study Session 10.

The collection of data on your EPI progress indicators during the year will help you to assess how well you are meeting the objectives of your action plan. You may need to revise your activities if monitoring and evaluation suggests that more needs to be done in order to achieve your objectives.

8.2 Immunization delivery at various sites

The second part of this study session describes how to implement your action plan depending on where you will be conducting the immunization session. Immunization can be delivered at various sites, each of which has some differences in terms of preparation and delivery. To increase immunization coverage, a combination of these three approaches should be used:

- Fixed-site service is delivered at your Health Post. Ideally, immunization should be routinely available on a daily basis, but this may not be possible in your setting. In order to increase attendance, the regular days should be fixed after discussion with community members.

- Outreach service involves Health Post staff and volunteers giving immunizations in the community on well-publicised dates and at well-known locations. Establishing an outreach immunization service on a regular basis, in addition to the service at your Health Post, is a key part of the approach in Ethiopia called ‘Reaching Every Infant/Child’.

- Mobile service involves a team going to remote or hard-to-reach parts of an area and staying there for more than one day to deliver immunizations, for example to pastoral or nomadic communities.

As part of your planning procedure, you should have determined the size of the target population in your kebele, and made a map of your area. This will help you determine which parts of the community can best be served by fixed-site immunization, and which by an outreach or mobile delivery service. The main difference between these three ways of delivering the immunization service is the method of maintaining the cold chain. We start by considering an immunization session at your Health Post, and then briefly describe the additional requirements for an outreach or mobile delivery service.

8.2.1 Setting up an immunization session at a fixed site

First, you need to prepare the area where you can give the immunizations and record what you have done, and you need a waiting area for children and their caregivers. The workplace should be in the shade so that you can keep your vaccines away from direct sunlight. It is also important to keep yourself and your clients from direct sunshine, dust and rain. You have to keep the working area clean and quiet to make it conducive for your work. For efficient immunization, you need to avoid the workplace becoming crowded.

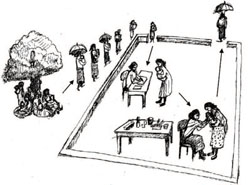

The example in Figure 8.8 shows the flow of people through a Health Post during an immunization session. Arrange the flow so that it can be in one direction only, to avoid clients who have already been vaccinated mixing with clients who are waiting for their turn.

You need a table for registration and recording and another table to put vaccines and accessories on. Ideally, there should be enough seats for carers to sit on while waiting for their turn. While they are waiting, this area can also be used to deliver information about immunization and to check the infant immunization record cards (Figure 8.9).

What resources do you need for a fixed-site immunization session?

Determine the number of vials you will need to take out of the refrigerator and place them in a vaccine carrier with the correct number of conditioned ice-packs. You should aim to open the refrigerator as few times as possible, preferably just once at the beginning and once at the end of the session. This is why it is important to estimate how many people you expect to come for vaccination at each session, so you can remove the right number of vaccine vials. Some multi-dose vials may have been opened and used in the previous session, so take them out of the ‘use first’ box and place them on the foam pad in a vaccine carrier above the conditioned ice-packs or chilled water packs.

You learned about the cold chain in Study Session 6, and about the multi-dose open vial policy in Study Session 7.

Check the quality of all vaccines and diluents as described in Study Session 6. Discard any vials or ampoules if the expiry date has passed, or if the vaccine vial monitor (VVM) has changed to the discard point, or any freeze-sensitive vaccines that have accidentally been frozen. Also discard any vaccine vial or diluent which has lost its label, because you cannot be sure what it is.

The other materials you will need for the immunization session include:

- source of water and soap for handwashing

- auto-disable (AD) syringes for immunizations and single-use disposable syringes and needles for mixing diluent with freeze-dried vaccines

- cotton swabs and antiseptic or alcohol for cleaning the skin at the injection site

- metal file to open ampoules

- stationery, including the immunization tally sheet, EPI Registration Book, pencils or pens

- new immunization cards for infants and women who have not come for immunization before

- safety boxes for syringes, needles and other sharp instruments, and another container for non-medical rubbish.

you will learn about registration and how to use the tally sheet to create your Summary Report in Study Session 10.

Deciding which vaccines to give an infant

Check which of the vaccines the infant has received before by looking at the information on the infant’s immunization card. If the carer has forgotten or lost the card, you should look for any entry for the infant in the EPI Registration Book. You can also look for a BCG scar on the upper left arm to establish if the infant has had the BCG vaccination. If the immunization card is lost, you should issue a new one. If you cannot establish whether or not the infant has been vaccinated before, it is advisable to give all the vaccines according to the national EPI schedule — unless there are contraindications. An extra dose of vaccine does not hurt most children.

Deciding whether to give a woman a TT dose

Check the immunization card of every woman of childbearing age who attends the clinic and give her the appropriate dose according to the TT schedule. If she does not have an immunization card, ask whether she has had any previous TT vaccinations, and whether she knows how many doses she has received in the past. Give her the next dose in the series. Take into account any dose given during an earlier campaign that might have taken place in your kebele. If she cannot remember or does not know, you should give her a dose of TT and advise her when to come for the next one. If she is pregnant, and has not received a TT dose in the past month, immunize her with TT vaccine.

8.2.2 Recording immunizations

Record keeping is an important part of every immunization session, whether it occurs at a fixed site or during outreach or mobile services. Study Session 10 describes the records in detail, so here we will briefly mention only the main points.

The Family Folder is not only for recording immunizations, but for all vital events (e.g. births, deaths, cause of death, etc.)

Before you immunize an infant or a woman you must enter all the required information into the EPI Registration Book, the Family Folder and the Immunization Tally Sheet. You should check that the infant is the correct age for immunization, and that the infant’s age on the immunization card is correct. (You will see examples of the EPI Registration Book, immunization card and tally sheet in Study Session 10.) Also, record the doses of vaccine given at each session in the Vaccine Stock Register shown in Study Session 5.

If this is the first time the infant has been brought for immunization, ask the age of the infant, and if the carer does not know the exact date of birth, try to find out the date by relating it to a historical event or national holiday, such as Easter or Eid Al Fetir.

The EPI Registration Book is an important record of your activity and the number of vaccine doses used. It also enables you to trace which vaccinations the infant has had if the carer fails to bring the immunization card on a future occasion. Record all vaccines and vitamin A supplements given on the tally sheet by counting the number of doses of each type of vaccine given during the session. Complete the tally sheet and the infant’s immunization card.

On the immunization card you should write:

- the date for each vaccine administered or vitamin A supplement given

- the date when the next immunization is due.

You should return the card to the carer, and before she leaves the Health Post, you should explain that:

- The immunization card is an important document about the health of the infant. She should keep it in good condition and bring it with her whenever the child is brought to the Health Post for any reason – not just when she comes for another immunization.

- The infant should complete the full course of vaccinations. Give the carer the date when the infant should be brought back for the next dose of vaccine.

- Occasionally there are adverse reactions to the immunization, but usually these are very mild and get better quickly. Make sure the carer knows what to do if they occur, and explain that the infant should be brought back if the symptoms get worse or the reaction continues for more than a day or two.

8.2.3 Immunization delivery at an outreach site

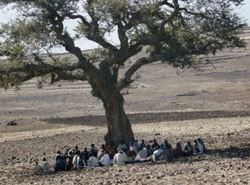

There are very few differences between delivery of an immunization service at an outreach site, and the details already described for a fixed site such as your Health Post. The key point is that the dates, times and sites for regular outreach sessions should be planned carefully, with the goal of covering the target population within the target period. It is very important to work with the community in selecting the most suitable sites and the most appropriate days for outreach immunization sessions. The site should be readily accessible, such as a school or kebele office, or in the shade of a large tree (Figure 8.10).

Training, assistance and supportive supervision should be provided regularly for you and the community volunteers in outreach sites, to ensure the delivery of safe and high-quality immunization services for the local community. Monitoring and evaluation of the outreach service, with community input, is crucially important for its success. Regular meetings should be organised to discuss ways of increasing the immunization coverage locally, for example by changing the location to a more convenient site or adding new outreach sites.

What resources do you need for an outreach immunization session?

Human and financial resources for outreach sessions require very careful management in order to reach every district in a sustainable manner. In addition to the resources already described for a fixed-site session, the community should help by providing chairs and tables, and local volunteers to assist you. When you arrive, inspect the site to check that it has been arranged correctly to ensure a good workflow (look back at Figure 8.8), and that all surfaces have been properly cleaned. Swab the table where the injections will be given with alcohol before you set out your equipment.

Make sure that your vaccine carrier or cold box is shaded from the sun!

Make sure that your vaccine carrier or cold box is shaded from the sun!What additional resources will you need to take to an outreach session, compared to a fixed-site session?

You will need to pack all your equipment safely to transport it over the required distance, while maintaining the vaccines and diluents under cold chain conditions at all times. This may mean that you need a cold box, which stays cold for longer than a vaccine carrier.

When you leave the outreach site, you should collect all the safety boxes and any other waste, and take them back to your Health Post, where you can dispose of them in a safe way (see Study Session 7). Do not leave any waste at the site. You started your work in a clean area and it is important to leave the site as clean as when you began. Make sure that you thank all the community volunteers who helped you deliver a successful immunization session that day.

8.2.4 Mobile delivery

During a mobile immunization programme, it is important to plan other health intervention activities, such as malaria control and antenatal visits, at the same time.

A mobile immunization service is likely to be most appropriate for pastoral and hard-to-reach areas. The key difference with other ways of delivering immunization is that it requires a mobile team to travel from place to place, carrying all the immunization equipment and maintaining absolute cold chain conditions for several days. The organisation of a mobile team requires careful planning.

Decisions about where to conduct the immunizations should be discussed and agreed with local government officials, community leaders and other stakeholders. Once the area is identified, you should use all possible ways to get information on the eligible target population in the area, so you can estimate what resources you will need for the number of sessions planned during this trip. Make sure that news reaches every community well in advance of the dates when your mobile service will be coming, and advertise where local people should go to meet you and your team. The setting-up and delivery of each session is exactly as already described for an outreach session.

In the next study session we turn to communication about the immunization service in more detail. Good communication is essential to ensure its success, wherever immunization sessions occur.

Summary of Study Session 8

In Study Session 8, you have learned that:

- Proper planning is a crucial step in all your immunization activities. If you do not plan properly, you are likely to fail in reaching your targets.

- Planning consists of six steps: assessing the community’s health needs, identifying and prioritising problems to be addressed, setting goals and objectives, agreeing strategies and activites in the annual action plan (including resource requirements), implementing the service, and monitoring and evaluating progress towards meeting the targets.

- Planning should be carried out in consultation with the district health team and kebele leaders, agreed with all relevant stakeholders and reviewed regularly.

- There are three types of immunization service delivery: fixed site, outreach and mobile services. Resource planning requires additional community participation at outreach or mobile delivery sites to set up the immunization workplace. The cold chain must be maintained at all times.

- At every immunization session, all required information must be entered into the EPI Registration Book, the clients’ immunization record cards, the Family Folder, the tally sheet and the Vaccine Stock Register.

- The mother or carer of each child brought for immunization should be given a clear explanation of the importance of the immunization record card, when next to bring the child and any possible adverse events following immunization, how to treat them and what to do if a reaction is serious.

Self-Assessment Questions (SAQs) for Study Session 8

Now that you have completed this study session, you can assess how well you have achieved its Learning Outcomes by answering the following questions. Write your answers in your Study Diary and discuss them with your Tutor at the next Study Support Meeting. You can check your answers with the Notes on the Self-Assessment Questions at the end of this Module.

SAQ 8.1 (tests Learning Outcomes 8.1 and 8.2)

Rearrange the following steps in the planning process into the correct sequence:

- setting goals and objectives

- assessing the community’s health needs

- agreeing strategies and activities in the annual action plan, including resource requirements

- implementing the immunization service

- monitoring and evaluating progress towards meeting the targets

- identifying and prioritising problems to be addressed.

Answer

The six planning steps in the correct sequence are:

- assessing the community’s health needs

- identifying and prioritising problems to be addressed

- setting goals and objectives

- agreeing strategies and activities in the annual action plan, including resource requirements

- implementing the service

- monitoring and evaluating progress towards meeting the targets.

SAQ 8.2 (tests Learning Outcomes 8.1 and 8.2)

Imagine you identify a number of problems in your catchment area which you think might prevent you from implementing your immunization programme effectively. You have considered the magnitude and severity of each of the problems you have identified.

- What else should you consider in attempting to prioritise these problems?

Answer

You should also consider the socioeconomic impact of reducing each problem, the feasibility of available solutions to each problem (are the required actions realistically deliverable, and do you have adequate resources?), and whether they are likely to be affordable within existing budgets. Another consideration in prioritising your activities is whether the beneficiaries in the community will find your solutions acceptable, and whether they meet local and government concerns.

SAQ 8.3 (tests Learning Outcomes 8.1, 8.2, 8.3 and 8.4)

Which of the following statements is false? In each case, explain what is incorrect.

- A Community discussion and approval is essential during the development of your annual immunization action plan.

- B If a mother has lost the immunization card for her child, you should send her home to find it before you agree to immunize the child.

- C The percent of newborns protected at birth from neonatal tetanus is a good indicator of progress towards achieving adequate TT doses for their mothers during pregnancy.

- D A fully immunized child has received all doses of all the EPI vaccines scheduled for routine immunization by the age of 14 weeks.

- E Accurate entries in your EPI Registration Book during each immunization session will help you to estimate the number of doses of vaccine needed for future sessions.

Answer

- A is true. Community discussion and approval is essential during the development of your annual immunization action plan.

- B is false. If a mother has lost the immunization card for her child, you should not send her home. You should question her carefully to see if she remembers what vaccines her child has received and the date of the last immunization. Check your EPI Registration Book to see if you can find an entry for her child’s previous immunizations and give the next dose accordingly. If there are no available records and there are no contraindications, give the child the appropriate EPI vaccines based on its age.

- C is true. The percentage of newborns protected at birth (PAB) from neonatal tetanus is a good indicator of progress towards achieving adequate TT doses for their mothers during pregnancy. The maternal antibodies developed by women who have had TT2+ within 2 weeks of delivery will protect their newborns from tetanus.

- D is false. A fully immunized child has received all doses of all the EPI vaccines scheduled for routine immunization — including measles vaccine — by its first birthday.

- E is true. Accurate entries in your EPI Registration Book during each immunization session will help you to estimate the number of doses of vaccine needed for future sessions.

SAQ 8.4 (tests Learning Outcomes 8.4 and 8.5)

After vaccinating a 6-week-old baby with BCG, OPV1, Penta1 and PCV10, you explain to the mother that she should look after her immunization card carefully, and bring it with her next time she brings her baby for immunization. You also explain the importance of completing the full course of immunizations.

- What else should you tell the mother before she leaves the Health Post?

Answer

You should also tell her to bring her baby for her next dose of these vaccines in 4 weeks’ time, at 10 weeks old, and explain that possible side-effects of the vaccines her baby received are mild swelling and soreness at the sites of vaccination and a slight fever, but these are nothing to worry about.

SAQ 8.5 (tests Learning Outcomes 8.5 and 8.6)

- a.What should community volunteers prepare for an outreach immunization session before you arrive at the site?

- b.What should be provided to support the community volunteers at this site?

- c.What should you do before leaving the site at the end of the outreach session?

Answer

- a.Before you arrive at an outreach site, the community volunteers should prepare the area for the immunization session by setting out a registration table and a table at which immunizations can be given, and some chairs or other places for clients to wait for their turn. The tables should be clean and the area should be tidy and well shaded, so that everyone is protected from sun and rain, and the vaccines are not exposed to heat or sunlight.

- b.Support for the community volunteers at the outreach site should be provided in the form of adequate training and supportive supervision, to enable you to deliver a safe and effective immunization service with their help.

- c.Before leaving the site at the end of the outreach session you should collect all waste and safety boxes for safe disposal back at your Health Post, and leave the area clean and tidy — just as you found it. Don’t forget to thank all the volunteers!