Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Thursday, 20 November 2025, 12:50 AM

Immunization Module: Communication for an Effective Immunization Programme

Study Session 9 Communication for an Effective Immunization Programme

Introduction

The Health Education, Advocacy and Social Mobilisation Module describes in depth the importance of communication in the health service and methods of achieving good communication. As you already know from earlier study sessions, a key part of a successful immunization programme is effective communication. Communication plays a major role in achieving the overall goal of increasing immunization coverage rates and reducing the number of infants and mothers who drop out of the programme (default) before completing all their vaccinations. This study session will deal with communication in the immunization programme in more detail.

Learning Outcomes for Study Session 9

When you have studied this session, you should be able to:

- 9.1 Define and use correctly all of the key words printed in bold. (SAQ 9.1)

- 9.2 Describe how you would plan and choose appropriate communication strategies to promote immunization activities and remove barriers to accessing the service. (SAQ 9.2)

- 9.3 Describe effective communication techniques to use with carers, members of the community and other stakeholders. (SAQs 9.1 and 9.3)

- 9.4 Explain how you would manage negative rumours about immunization in your community. (SAQ 9.4)

9.1 Why is communication crucial for an effective immunization programme?

Advocacy and communication form one of the five key EPI operations (Figure 9.1), which you saw first in Study Session 1. Advocacy refers to ways of delivering an argument effectively, so that you gain the support and commitment of policy-makers, community members and other stakeholders, and are able to ‘put the case’ successfully for increasing immunization coverage. Communication is the transmission of information from one person to another, or from a source to a destination.

Immunization programmes may be unsuccessful if incorrect or inadequate information is transmitted to the community. Sometimes, even though correct information may be communicated, it may be ineffective in achieving the desired outcome. It is important that you, as a Health Extension Practitioner, use terms that are readily understood when you talk to members of the community, ensuring that you appreciate local problems and show respect for local customs and culture. One way to improve communication with members of your community would be to organise a committee to look into reasons why people do not come to be vaccinated, or do not complete their vaccinations. This would help you to:

- improve relations between you as a Health Extension Practitioner and the community

- promote participatory decision-making to improve community involvement in the EPI

- support the community to develop strategies for identifying and tracing immunization defaulters

- improve the quality of the immunization service

- encourage the community to identify and report outbreaks of communicable diseases.

What do you hope this would achieve in the long term?

The hope is that this would increase immunization coverage in your kebele and help high immunization coverage rates to be maintained. If more infants and mothers are fully immunized, then disease and deaths from vaccine-preventable diseases will be reduced.

9.2 Planning a communication activity

A communication strategy should be included in your annual EPI action plans. There are likely to be many possible barriers to effective communication between Health Extension Practitioners like you, carers, the community and stakeholders. It is important that you identify these barriers and do your best to eliminate them. The aim is that your messages will be understood and will result in changes in behaviour, which will increase EPI coverage rates and decrease dropout rates.

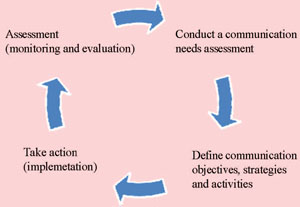

The planning process involved in communication for improving immunization coverage can be summarised in a series of four steps as outlined in Figure 9.2; this is a simplified version of the six-step diagram you have already seen in Study Session 8 (Figure 8.3).

9.2.1 Conduct a communication needs assessment

First, it is important to talk to people to find out about attitudes to immunization in the community, in particular whether there is opposition to it. If there is some resistance to immunization, you need to ask why this has occurred. Discussion with members of women’s groups and youth groups in your kebele may help you to find answers to your concerns. You may be able to identify specific behaviour or attitudes that are creating a barrier to immunization in the community. Has there been an adverse incident in the past that has worried parents? Is there an opinion leader in the community who is opposed to immunization and has persuaded others to resist it? This communication needs assessment will help you to assess what strategies and activities to plan for this community.

9.2.2 Define communication objectives, strategies and activities

If you can identify specific barriers to immunization, you will need to decide which of these might be targeted in order to look for a solution. Which of these barriers might it be possible to remove? How might this help to increase immunization coverage and decrease dropout rates? Why are so many children not brought for immunization? Table 9.1 lists some commonly reported reasons.

| Reason why child not fully immunized | Caregivers giving this as the main reason (%) |

|---|---|

| Unaware of need for immunization | 22.8 |

| Unaware of need to return for next dose | 12.8 |

| Vaccine not available | 12.5 |

| Mother too busy | 6.3 |

| Vaccinator absent | 6.1 |

| Place and time of immunization unknown | 6.0 |

| Immunization site too far away | 5.7 |

| Family problems and/or mother ill | 5.3 |

| Fear of adverse effects following immunization | 4.0 |

| Time of session not convenient | 2.6 |

Stop reading for a moment and think about which of the reasons in Table 9.1 are the most likely reasons for children not being brought for immunization in your catchment area.

These are the issues that you should concentrate your communication efforts on, and that should form the basis of your communication objectives.

Which of the reasons listed in Table 9.1 do you think could be best addressed by improved communication? How might you hope to address these barriers to an effective immunization service?

Many of the reasons given in the table could be addressed by improved communication, but in particular you might have suggested:

- Unaware of the need for immunization: You could arrange a community meeting to explain the advantages of immunization, and the seriousness of the diseases it protects against.

- Unaware of the need to return for the next dose: You could ensure that all those bringing their children for immunization are clearly told when they should return and why.

- Place and time of immunization unknown: You can make sure there are notices clearly visible at your Health Post and in the kebele office announcing when and where immunization is available. You can also make every effort to remind people of these dates and places whenever you visit families, and ask your volunteers to tell everyone they visit.

- Fear of adverse effects: Whenever you are telling people about the advantages of immunization and the seriousness of the diseases it protects against, you could also explain that there may be mild side-effects, but that these are very rarely serious.

Setting objectives

You will recall from Study Session 8 that objectives always have to be specific and the outcomes must be measurable. A well-constructed objective identifies what will be done in order to achieve it, who will do it and where, what resources will be used, and the timescale in which the target should be achieved. You will also need to work out what resources are available in the community that can be used for the communication activities that you may wish to organise.

Having set your communication objectives, you next need to decide what activities would be the most appropriate to help you to achieve them. You should address the following questions:

- What message is it that you want to communicate?

- What media will be most suitable for communicating it?

- Will you be able to get the resources required?

Strategies and activities

There are a number of possible strategies or activities you can use to get your message across to the community. These might include a community conversation (Figure 9.3 and see Section 9.3.4 later in this study session) or a community mobilisation or advocacy programme. The work plan for conducting these activities should be realistic. You will need to think about what it is that you want to do, when you hope to do it, how many people you will need to help you and who these people might be.

Assessment, monitoring and evaluation

You will also need to find ways to check whether your strategy or activity is working. For example, you might have held a meeting or conducted a community conversation to explain the advantages of immunization, and the seriousness of the diseases it protects against. You hope that this might increase immunization coverage by encouraging caregivers to bring their children to the Health Post for immunization.

How could you evaluate whether your message was understood and whether it has made a difference to people’s behaviour?

There are many possible ways you might try to evaluate the effectiveness of your activities. Here are some suggestions (you might have thought of others):

- You could record how many people attended the meeting or community conversation, and who they were. You could then monitor how many of these people have shown a change in behaviour. You could see if these people brought their children for immunization, or brought them more regularly than before.

- If someone who is not known to you brings their children for immunization for the first time, you could ask how they knew the immunization was available. This might help you to establish whether those who were present at the meeting or community conversation spread the message to others.

If you look back at Figure 9.1, you will see that it is a circle. This is because the results of your monitoring and evaluation help you to determine which strategies and activities are making progress towards achieving your objectives. This information should be fed back into your next communication analysis, so communication improves when you find out about people’s attitudes and behaviour next time.

9.3 Behaviour change communication (BCC)

You will probably be aware that firmly held views do not change fast. It takes time for people to change their attitudes. The aim is to increase immunization coverage, so the goal of communication about immunization is to bring about positive behaviour change. When you deliver messages to people they may understand what you are saying and acquire knowledge about immunization, but they may not take this knowledge and apply it. They still may not bring their children for immunization. They may not actually change their behaviour.

Behaviour change communication (BCC) is a process of developing communication strategies to promote a positive change in health-related behaviours in a community, appropriate to local circumstances. This can only be done by sustained work with individuals and communities to explain the issues and implications involved and support people as they try to understand them.

9.3.1 Common methods of BCC in immunization

When you want to communicate a message, for example about the advantages of having your child immunized, you should first identify or decide who the message is intended to influence. The message to be sent to a group of school teachers, a women’s group, a youth group, or a group of religious leaders is not the same, even though the aims of all these messages might be to increase immunization coverage. Their level of understanding of the issues involved is likely to be quite different. Therefore in preparing a BCC message, the first step should be to decide who you intend to address. This is your target audience.

Suppose the message you want to communicate is that there are many diseases that are serious and may lead to death, but they can be prevented by immunization; therefore, bringing babies and children for immunization from an early age is beneficial. Who would your target audience be? (Who would you want to communicate this message to?)

You would want to communicate this message to all mothers of babies and children (Figure 9.4), and any other caregivers in the kebele who are responsible for looking after babies and children.

Once you have identified your target audience, the next step is to think about your objective. What change in behaviour do you want your target audience to make? This could be based on the problems you have identified in your communication needs analysis. There are several strategies and activities that you can use, including advocacy, community mobilisation, community conversations and interpersonal communication — all of which are explained in detail in the Health Education, Advocacy and Community Mobilisation Module, Part 2. We will remind you of the main points below.

9.3.2 Advocacy

Advocacy is a process or activity that aims to influences politicians, policy-makers and opinion leaders. In the context of EPI activities, this could refer to an activity that aims to gain the support of stakeholders, community leaders and local politicians, and to encourage community acceptance of and commitment to the EPI. There are many activities and strategies that can be used in advocacy. Here are some of them:

- lobbying

- meetings

- negotiation

- project visits

- use of information and education resources.

Imagine that a new vaccine is being added to the routine EPI schedule, but no decision has yet been reached about when it will be available for your kebele. You may need to undertake some advocacy activities in order to speed up the decision to make it available locally. What do you think the most appropriate activities might be in this situation?

Appropriate advocacy activities might include negotiation with local political and community leaders, as well as women’s and youth groups. You will need to provide them with information on the new vaccine, its safety, the diseases it can prevent and the particular needs of your community to receive its protection.

9.3.3 Community mobilisation

Community mobilisation is a process of gaining the involvement of everyone in the community for an action towards a particular goal.

Can you remember some of the advantages of the community mobilisation process?

You may not have remembered all of the advantages, but your answer should have included some of the following.

Community mobilisation:

- helps motivate the people in the community through participation and involvement of everyone in a shared goal

- builds community capacity to identify and address community needs

- helps mobilise and release local resources

- promotes long-term commitment to sustained behaviour change and hence sustainability of health improvements

- motivates communities to campaign for policy changes to respond better to their health needs

- links members of the community to the available health services

- leads to a feeling of local ownership, which ultimately leads to a more sustainable immunization programme.

In the EPI, mobilising the community is likely to enhance the programme and hence make it much more effective. In order to mobilise the community you will need to interact with your target audience members in person. You should prepare your message in a clear and simple way. You can have the interaction in community meetings, in religious places, market places, etc. Loudspeaker messages for large community meetings may be appropriate.

You may need to use written materials — for example, you could put up posters and distribute leaflets. Drama shows and local community radio broadcasts may also help your communication messages to be heard and understood.

9.3.4 Community conversation

One of the ways in which it is possible to influence behaviour is through a community conversation (Figure 9.5). This is a collective discussion of a particular issue, such as the causes of high dropout rate in the immunization programme, and can lead to a way of finding solutions to particular problems.

Such a conversation will be successful when everyone is given the opportunity to be heard. Many will not participate fully in a meeting unless they feel at ease and believe their opinions will be heard. Therefore in organising a successful community conversation, you should consider the following points:

- Decide on the purpose of the conversation and advertise it widely.

- Decide who should attend or be invited.

- Prepare an agenda for the meeting.

- Decide on the date and time; make sure that everyone you want to attend is informed about when and where the meeting will take place.

- Choose a meeting place where there is little interference, so that everyone will be able to hear one another’s views.

- Facilitate the conversation in an open and non-judgemental way, so everyone feels included and respected.

9.3.5 Interpersonal communication

Interpersonal communication is a term for face-to-face interaction with an individual, or a small group of people, for the exchange of information. Because it is a face-to-face interaction, the people involved have eye contact, they hear each other, and they can respond to each other’s ideas. Note that interpersonal communication is a two-way process, where everyone learns from each other — including you!

Interpersonal communication is vitally important in supporting the behaviour change process. In particular it is very good for:

- Persuading and convincing individuals and target audiences about the value of the proposed behaviour change, by explaining and responding to questions and doubts about immunization.

- Addressing rumours about adverse effects of immunization.

- Addressing any personal issues the caregivers may express.

- Helping to mobilise resources from the community to enhance the immunization programme, through advocacy efforts.

- Building consensus for a concerted effort, for example to bring all eligible children for immunization.

- Explaining to caregivers about the immunization status of the child.

- Telling the caregivers about the next immunization(s) that the child will need.

Interpersonal communication skills

Here is a reminder of the important interpersonal communication skills you learned about in the Health Education, Advocacy and Community Mobilisation Module.

- Welcome the client warmly and offer a seat.

- Empathise with the client.

- Speak in simple terms, using easy language; give examples that the caregiver is likely to understand.

- Motivate by praising the caregiver for bringing the child for immunization and encouraging them to return for the next dose.

- Listen actively. Active listening is very different from just hearing. It is listening to another person during a conversation in a way that shows your understanding and interest. It encourages the other person to be more involved in the conversation. You can show that you are actively listening by using gestures, saying ‘Aha!’, or repeating what the client has said (Figure 9.6).

- Use appropriate visual aids. The pictures you use should be relevant to the message you want to transmit, and appropriate to the local customs.

- Summarise what has been discussed at the end of the conversation. You should check and confirm areas of agreement and disagreement.

Asking questions sensitively

It is important to give your client a chance to ask questions. This will help you to see how much she has understood and accepted what you have discussed. You can also ask her questions that enable you to assess her attitudes and the likelihood of positive behaviour change. But questioning must be done sensitively!

What questions might you ask a mother in one-to-one interpersonal communication if you think she may drop out of the immunization programme?

There are many questions you might ask, for example the ones suggested below. You may have thought of others.

- Ask specific questions such as ‘Which immunizations did your child have last time? How was his health afterwards? Did you have any concerns about the vaccination?

These questions help you to establish whether the mother understands which immunizations the child has had, and which ones remain to be completed.

- Ask ‘Is there anything that makes you feel unsure if you will bring your child back for the next immunization?’ If she says she is unsure, gently ask about her worries and try to reassure her.

Asking about a caregiver’s worries about immunization is an example of an open question, i.e. a question that encourages the client to answer in her own way and share her concerns with you. You should avoid asking closed questions where the caregiver can simply answer ‘Yes’ or ‘No’. A closed question does not allow you to check whether the client has really understood the question, or really knows the answer.

Here is an example of a closed question: ‘Did your child complete all her immunizations?’ Change this into an open question on the same topic.

You could ask ‘Which immunizations has your child been given, and what age was she when she got them?’

When asking questions, always give time for the client to think and answer. Let the client answer freely and do not interrupt while the client is answering.

9.4 Meeting with target audiences to promote EPI activities

In your efforts to increase immunization coverage and decrease dropout rates, you are likely to come across various interested groups of people and organisations. These may include health staff at various levels, politicians and policy-makers, community leaders, representatives from the private sector and from the NGOs (non-governmental organisations, such as UNICEF, AMREF and others), parents, and journalists. You may also particularly want to meet people from those parts of the population that have not yet been reached by the immunization programme. In this section, you will learn ways to promote immunization campaigns when you contact representatives from these target groups.

9.4.1 Meeting with community leaders

Community leaders may include kebele leaders, clan leaders, religious leaders, elders and school leaders, and the leaders of women’s and youth groups. You should try to gather information about the community you are working in before you meet such community leaders. To increase the effectiveness of your meeting, you should identify who the relevant participants will be, decide on an agenda and what issues to discuss, and make sure that all those you want to attend the meeting are aware of the agenda, and where and when to meet. To gain the maximum benefit from the meeting, try to find out beforehand what the participants already know about immunization. It is based on this background that you can introduce the topic and build up useful discussions.

What issues might you want to discuss with community leaders?

Some possible issues are listed below. You may have thought of others:

- any concerns the leaders and families may have about immunization

- any religious or traditional beliefs about disease or immunization

- barriers that may prevent people from accessing immunization services, e.g. distance, seasonal work commitments, traditional festivals or customs, lack of money for transport, and inconvenient days, times or sites for immunization sessions

- the most appropriate times and locations for immunization sessions

- possible ways of reaching more children in the community

- whether immunization could be promoted by being mentioned regularly at religious or other gatherings.

9.4.2 Meeting with parents

One of the most effective ways to get a range of opinions in a short space of time might be to arrange small focus groups, with clear guidelines from you about the topic that the discussion should ‘focus’ on. The ideal number of participants in a focus group is between six and ten, with a facilitator who keeps the discussion focused on the agreed topic (in this case, immunization) and makes sure that everyone’s views are heard. You could select particular participants, such as parents you think may be unlikely to bring their children for immunization.

You may also talk to parents one-to-one when they visit the Health Post and find out about their experiences (good and bad) with the immunization services provided. In particular, you should try to reach those parents in the community who, for one reason or another, do not visit the Health Post. Interview the mothers who do attend the Health Post first, since they are readily accessible and are often willing to talk about their experience of the services. In addition they may suggest ways of reaching those who do not use the Health Post facilities.

When meeting with parents, what might you want to find out?

There are many things you might want to find out from parents, but here are some things you may have suggested:

- what they already know about immunization

- what concerns they may have about immunization

- their traditional beliefs about disease or immunization

- any barriers to accessing existing services

- if the times and locations of immunization sessions are appropriate

- what they think about the quality of the service provided

- how they think the service could be improved.

9.4.3 Meeting with NGOs and other partners

Try to meet with any other partners or institutions who you think might be able to help improve the immunization service. Who these might be will depend on your community, but could include traditional birth attendants (TBAs), traditional healers, private health practitioners, volunteer groups and representatives of NGOs that focus on health — particularly the health of children.

9.4.4 Meetings with special groups

In your community you may be aware of some special groups who have been largely unreached by immunization services, or have chosen not to participate in them. You should try to include such people or groups in your meetings and planning process right from the start. Some examples of special groups include:

- pastoralist groups

- migrant workers

- ethnic or other minority groups

- groups in geographically remote areas, who may find it difficult to reach the site of the immunization services

- people who are injured, sick or disabled, who may find it difficult to get to where immunizations are taking place

- religious or traditional sects that refuse immunization

- refugees

- homeless families.

You should always try to ensure that your messages are concise and to-the-point, and also that they are memorable. This is particularly important in meetings with representatives from any of the special groups mentioned in this section. In the final part of this study session, we turn to some of the negative rumours about immunization that might influence people against the service in your community.

9.5 Negative rumours about immunization

Rumours about bad consequences of immunization often circulate in communities. If such negative rumours are not dealt with appropriately, they can cause serious problems for the effective delivery of immunization services.

Can you think of any rumours about immunization in your kebele? If so, what are they?

Examples of some rumours that may be circulating are that:

- vaccines are a contraceptive to control births in the population, or to limit the size of a certain ethnic group

- children are dying after receiving vaccines.

You may have come across other rumours, which could be equally damaging to the success of an immunization programme.

What can you do about negative rumours? Any negative rumours about immunization that you hear are circulating should be communicated to your supervisor as soon as possible. The following suggested actions cannot be carried out by you alone, as the local Health Extension Practitioner; you will need the full involvement of health centre officials and the district Health Office. Immediate reporting is important and advice should be sought before you take action.

With their approval, these are the steps you should take if you come across a potentially damaging rumour about immunization:

- First, try to find out what the rumour is, who was the original source of the rumour and who is spreading the rumour now. Try to establish whether there is any reason for the rumour spreading — there might be a political or religious reason, or it might simply have arisen from lack of information or incorrect information about the immunization programme.

- Once you have gathered this information, arrange a meeting with opinion leaders such as local government officials, traditional and religious leaders, community leaders and other health workers. In the meeting, begin by providing information about the immunization programme and the diseases it can prevent. Try to ensure that those present are free to ask questions and express concerns. Discuss and reach agreement on collective ways to correct the negative rumour and the wrong information about the immunization service.

- Train your community volunteers on how to give the correct information about vaccines and how to deal with the rumour.

- Distribute posters and printed materials which give correct information about immunization to the public. Such materials may be made available by your local health centre or to support regional or national campaigns.

In the final study session in this Module, we turn to a crucial aspect of your immunization programme — monitoring and evaluating the outcomes.

Summary of Study Session 9

In Study Session 9, you have learned that:

- Barriers to accessing the immunization service include issues that can be resolved by better communication. These barriers include lack of knowledge about the need for immunization or the need to return for further doses, or about the time and location of immunization sessions; fear of adverse reactions is another barrier that good communication can overcome.

- Immunization coverage rates can be increased and dropout rates reduced by effective advocacy and communication activities; inadequate communication with local people, in particular parents, can seriously affect the success of the immunization programme.

- Behaviour change communication (BCC) activities should be an integral part of your planned immunization strategy; the planning process involves a communication needs assessment, the definition of communication objectives, strategies and activities, implementation, and assessment of outcomes through monitoring and evaluation.

- You should select BCC strategies and activities appropriate to the target audience, local culture and context, such as advocacy, community mobilisation, community conversations, interpersonal communication and focus group meetings, e.g. with community leaders, parents, women’s groups, youth groups, NGOs and other partners, and special groups — particularly those who have not yet been reached by the immunization service, or are reluctant to access it.

- You should seek guidance from your supervisor and district health officials on how best to address negative rumours about immunization if they circulate in your community.

Self Assessment Questions (SAQs) for Study Session 9

Now that you have completed this study session, you can assess how well you have achieved its Learning Outcomes by answering these questions. Write your answers in your Study Diary and discuss them with your Tutor at the next Study Support Meeting. You can check your answers with the Notes on the Self-Assessment Questions at the end of this Module.

SAQ 9.1 (tests Learning Outcomes 9.1 and 9.3)

- a.What is meant by a community conversation?

- b.In what circumstances might you arrange a community conversation about your immunization programme?

- c.Who would you invite?

Answer

- a.A community conversation is a process of discussion with a community group. It looks into an issue that is causing problems locally and seeks to find collective solutions to these problems.

- b.There are many situations where you might decide to arrange a community conversation about your immunization programme; for example:

- If you have large numbers of families who do not bring their children for immunization

- If you have a high dropout rate from the immunization programme in parts of your kebele

- If children have had serious adverse reactions after immunization

- If you believe there are negative rumours circulating in the community about immunization.

- c.The appropriate people to invite will depend on the situation:

- If you have large numbers of families who do not bring their children for immunization, you could invite representatives of those families and also any of their neighbours who do bring their children for immunization.

- If you have a high dropout rate from the immunization programme in parts of your kebele, you could invite parents from families whose children started their vaccinations, but did not complete them.

- If children have had serious adverse reactions after immunization, you might invite the parents of those particular children, together with other parents whose children were not adversely affected.

- If you believe there are negative rumours circulating in the community about immunization, you might invite those who you believe are being influenced by the rumours, together with community leaders and other influential people in your local community who support immunization.

SAQ 9.2 (tests Learning Outcome 9.2)

Supposing you wanted to increase the low immunization coverage rate in one particular group of parents in your kebele. What steps would you take in the planning process to address this problem?

Answer

The steps you should undertake in planning your strategy are:

- Communication needs assessment — try to find out which parents are not accessing the immunization programme and why this might be.

- Set specific and measurable objectives — identify what barriers need to be removed in order to improve coverage rates, and what communication activities might support this goal. Establish what community resources you might have available to address the problem.

- Plan appropriate strategies or activities, e.g. a focus group with parents, a community conversation, a meeting with opinion leaders, etc.

- Prepare your action plan — decide when and where the communication activities will take place, who will lead them, who will be invited, how you will advertise the event and ensure the right people attend it.

- Implement your plan.

- Monitor and evaluate the outcomes of your communication activity — record how many people took part, and whether they changed their behaviour afterwards and brought their children for immunization.

SAQ 9.3 (tests Learning Outcome 9.3)

Suppose that you find the main reason given for high dropout from the immunization programme is a lack of awareness of when or where immunizations take place. What measures might you take to improve the situation?

Answer

Lack of accurate knowledge about the immunization service could be improved by better communication. You should make sure that you communicate the times and places for the immunization sessions effectively, so that they are known to everyone. You could do this by posting notices where they will easily be seen, telling all your clients when you see them at the Health Post, or in their homes, at the market, etc., and asking your community volunteers to tell everyone they visit. You could ask community or religious leaders to announce the dates and locations of immunization sessions during their own meetings.

SAQ 9.4 (tests Learning Outcome 9.4)

Imagine that you discover there is a rumour circulating in your kebele that measles vaccination causes deafness. What would you do?

Answer

If you discover such a rumour, you should do the following:

- Report the rumour and seek advice from your supervisor and health centre officials about how to deal with it.

- Collect information about the rumour — who has started it? Why do they think that measles vaccination causes deafness? Has the rumour started because of incorrect information, or is there some other reason?

- Meet with opinion leaders — give them an opportunity to ask questions, and provide clear information about the dangers of measles and how vaccination can prevent it.

- Train community volunteers to give correct information about the measles vaccine and how to deal with the rumour.

- Arrange meetings with concerned parents to communicate correct information about measles vaccination.

- Prepare posters and print materials and distribute them around your kebele explaining in simple local language about the benefits of measles vaccination and that it very rarely causes any bad effects.