Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Monday, 9 March 2026, 10:54 AM

Module 1: Module 1 - Childhood and children’s rights

Introduction to Module 1

This is the first module in a course of five modules designed to provide health workers with a comprehensive introduction to children’s rights. While the modules can be studied separately, they are designed to build on each other in order.

Module 1: Childhood and children’s rights

Module 2: Children’s rights and the law

Module 3: Children’s rights in health practice

Module 4: Children’s rights in the wider environment: the role of the health worker

Module 5: Children’s rights: planning, monitoring and evaluation

Module 1 of the curriculum provides an overall introduction to childhood and the idea of children’s needs and rights. An understanding of these issues will be necessary in order to make sense of the following modules on how to respect children’s rights in your role as a health worker. The module comprises three study sessions, each designed to take approximately two hours to complete. The sessions provide you with a basic introduction to the subject and are supported by a range of activities to help you develop your understanding and knowledge. The activities are usually followed by a discussion of the topic, but in some cases the answers are at the end of the study session. Please compose your own answer before comparing it with the answer provided. We have provided you with space to write your notes after an activity, however if you wish, you can use a notebook.

- Study Session 1 explores what we mean by childhood, how it is understood in different societies and some of the characteristics of being a child. It examines how children can be treated differently depending on whether, for example, they are a boy or a girl, or if they have a disability. And it provides you with an opportunity to explore your own attitudes towards childhood and how children should be treated. By the end of the session, you should have developed some insight into different approaches to understanding childhood, have a better understanding of your own views and behaviours towards children and be able to recognise some of the ways in which childhood is a unique and distinctive phase of life.

- Study Session 2 builds on the learning about childhood from the previous session and introduces you to the different stages of development in a child’s life. It provides an overview of some of the key changes that take place in children’s development from birth through to adolescence. It also examines the factors that influence how well children develop, such as social and economic conditions, the opportunities for children to learn and play, and the encouragement provided by key adults in the child’s life. By the end of the session, you should have a broad understanding of the different aspects of child development and at roughly what ages children should acquire different skills, knowledge and capacities. You should also have a clear idea of why knowledge of child development is important for you as a health worker, and how to use that knowledge.

- Study Session 3 explores the different needs children have if they are to grow up healthy and well. It examines how, although all children have the same needs, the way those needs must be met will change gradually as children grow older. The session then introduces you to the idea that there is wide international agreement that all children have the same needs and that adults have responsibilities for making sure those needs are met. This has led to a recognition that children are entitled to have needs met – in other words, they have rights. By the end of the session, you should have a clear understanding of children’s needs, the obligation of adults to meet those needs and the relationship between needs and rights.

1 Understanding childhood

Focus question

What do you understand by childhood?

Key words: child, childhood, dependency, evolving capacities, resilience, risk, vulnerability

1.1 Introduction

Both national laws in East Africa and international agreements define a child as anyone up to 18 years of age. They recognise childhood as a period of nurturing, care, play and learning in the family, school and community. However, every society and culture also has its own understanding of childhood and who it considers to be a child. This session will examine how children and childhood are understood in East Africa, the factors that influence how childhood is defined and some of the key characteristics of childhood. It will help you explore your own attitudes and values in relation to children and look at how those attitudes differ towards different groups of children. As a health practitioner it is important to understand and re-evaluate how your own views on children and childhood influence your day-to-day practice.

1.2 Learning outcomes

When you have studied this session, you should be able to:

- define and use correctly the key words

- define who is a child

- describe the key characteristics of childhood

- understand how different cultures influence childhood

- reflect on and re-evaluate your own understanding of childhood.

Activity 1.1: Remembering what it feels like to be a child

Remembering your own childhood experiences is a good way of helping you understand what it feels like to be a child. If you can recall how you felt when good and bad things happened to you, you can be more sensitive to the behaviour and responses of children you work with now.

Look back at your childhood experiences. Spend 5 minutes thinking about how it felt being a child. Then think about:

- An occasion, event or experience that made you feel happy.

- An occasion, event or experience that made you feel sad, worried or frightened.

Discussion

Looking back at your childhood experiences may have helped you remember some of the things you liked and made you happy. They could have been things like special clothes or food, ceremonies, visiting friends or games you liked to play. It could have been an achievement like winning a prize that made your parents and teachers praise you. On the other hand, thinking back could have reminded you of things that frightened you, certain people, certain animals, remembering someone dying, being in the dark, being taken to hospital, or even getting an injection. You might have remembered times when you were treated unfairly, not listened to, punished or beaten by your teachers, parents or other adults.

These memories can help you understand how significantly the behaviour of adults affects children’s emotional well-being. Children can be very vulnerable to the way adults respond to them. Praise, criticism and neglect can often have lasting implications in a child’s life – it is easy to forget this. By recalling your own experiences, you can become more sensitive to the impact of your tone of voice, words, attitudes and actions on a child.

1.3 Who is a child?

Having explored some memories from your own childhood, this section moves on to explore what we mean by childhood, and how we define ‘a child’.

Although the law clearly states that a child is anyone who is under 18 years of age, this is not the way many people would define a child. The way a child is defined depends, to a very large extent, on the social, economic and cultural factors in a society. Factors such as tradition, community ideas, behaviour, physical development, place of residence, or the conditions a child is living in, can all determine whether or not a person is considered a child.

Until what age are boys and girls defined as children in your culture?

In most societies in East Africa, children are defined by their physical development, ability, responsibilities in the household and social status, rather than by the number of years they have lived. In the biological sense, a child is any person regardless of age and station in life. In a social sense, a woman or an unmarried/uninitiated man may remain a child for ever. A man may only be considered an adult when he marries and produces children. A woman is no longer seen as a child when she has given birth yet she may be considered a ‘perpetual minor’ and not be recognised as an independent individual without reference to her father, husband or male relatives.

The passage to adulthood is frequently marked by ritual or initiation around the time of puberty; however, these practices vary widely. In some cultures, male adolescents are required to be circumcised before they are regarded as adults; however, the age of circumcision can range from under 16 to over 26 years old. Even after this, full adulthood is not attained until marriage and the establishment of a family. In cultures where male child circumcision and female genital mutilation are practiced as initiation into adulthood, once boys or girls are circumcised, they are no longer regarded as children but rather as adults ready to marry and have children, regardless of their age. Examples of such cultures in East Africa are the Bagisu and Kukusabin of Uganda and the Karengin and Babukusu of Kenya. Among the Bagisu and Babukusu, for example, it is offensive to refer to a circumcised male as a boy (Musinde), even when he is as young as 14 years, because this means uncircumcised. The circumcised male builds himself a grass thatched hut (Simba) and no longer lives in the same house as his parents.

Some initiation practices, however, do have other serious consequences. Female genital mutilation is associated with many devastating physical, emotional and psychological implications for girls throughout their lives, particularly in relation to childbirth. It is in recognition of this that there are laws in most countries limiting these practices. You will look more at the importance of the law in Module 2.

Some African families or communities tie the concept of child to the physical ability to carry out specific tasks. These decisions are influenced by any of several factors, which may include economic status, level of education or location (rural or urban). Children from poor families and low educational status are seen in their societies to reach adulthood earlier than those from affluent and educated homes. It is not surprising therefore to find one 12-year-old child being deemed old enough to be an ‘adult’ for purposes of babysitting younger siblings, while another child of the same age may be deemed too young to be left alone, let alone responsible for another child. In some circumstances someone under 18 might have become the head of the household. In summary then, there are widely differing views on the definition of a child even within East Africa.

Activity 1.2: Definition of a child

Look at the images above and spend at least 15–20 minutes answering the following questions:

- Would you define the people in the photographs as children?

- What determines whether you think they are a child or an adult?

- List the positive and negative consequences for children caused by the way they are defined.

If you are working in a group compare your views. If your answers are different why do you think that is?

Discussion

Your responses to whether the people are seen as adults or children may depend on your own cultural background and education. If you are not from the same community as the children in the images, you may view them differently from how they are seen within their own community. Factors that determine how they are viewed might include whether or not they are married, whether they have been circumcised, whether they are a boy or a girl, how physically strong they are, whether they have children. The purpose of the activity is for you to start thinking about why there are variations in the way people define a child. It is important in these study sessions that you question your own assumptions about children, how they are defined and how they are treated. This includes the difference between girls and boys.

The extent to which you see the positives and negatives of how children are defined will also be influenced by your own experiences and beliefs. As a health professional you need to understand the harm that children can experience if they are exposed to hazardous work or to marriage too early, and the benefits of allowing a more extended period of protected childhood and education. Because of this understanding, some of these practices such as early marriage, are now prohibited by law or, as in the case of education, actively promoted. Just because something is common or part of a long-established culture does not mean it is acceptable or inevitable.

1.4 How is childhood understood?

In both Western societies and some sections of African societies, childhood is commonly considered to be a period of extended economic dependence, protected innocence and rapid learning through schooling. Childhood describes a period of life when young people are vulnerable both in the physical and mental sense, and hence ‘suffer’ from immaturity, a weak intellect and the inability to make decisions in their own best interests. Children are viewed as relatively helpless and dependent on adult protection and control.

By contrast, in many rural or otherwise traditional African societies, childhood is seen as a period of ‘training’ in preparation for a child’s entry into the harsh world of adulthood. Rather than a period of total dependency in which the child receives adult protection, childhood is understood in terms of obligations of support between generations. So, a child is always a child in relation to his or her parents who expect, and are traditionally entitled to, all forms of support from the child in times of need. Childhood in Africa also tends to be a period of internalised and rigorously enforced obedience to authority. The family is not only responsible for training and socialising children into adulthood, but is also entitled to determine what a child can and cannot do, and what processes need to be undertaken before they graduate to adulthood.

So views on the nature of childhood vary widely. In one place it will be seen as preferable to protect a 10-year-old from economic or domestic responsibilities. In another, such responsibilities are not only the norm, but are deemed beneficial for both the child and the family.

It is clear from this exploration of children and childhood, that these issues are more complex than we often assume. The way we think about them may differ significantly from the way people in other communities think about them. And the way we think will influence our attitudes towards children, and how we treat them. Some of these attitudes in East Africa derive from traditional cultures, while some are beginning to change as communities are increasingly exposed to different ideas.

Childhoods – tradition and change

Below are some examples of traditional and changing childhood experiences in East Africa.

Naming and birth rituals

One of the first activities in all societies is giving a name to a baby. In some cultures, parents choose the name but in others, naming is an important ceremony conducted by elders and followed by feasting. Cultures vary considerably in the way they decide on names: children might be named after the dead, according to birth order, based on events, according to biblical or religious characters, or even celebrities. Whatever the origin, a name carries a lot of meaning and it is a lifelong form of identity. The umbilical cord is so significant in some cultures that a baby will not be taken outside the house until it breaks off. Some cultures in Africa expect the mother to jealously protect the umbilical cord after it breaks off because it is used by elders to prove the true belonging of a baby to a clan. In Buganda, a tribe in Uganda, newly born babies are washed with herbs (kyogero) rather than soap for the first month. The reason is to give a baby a smooth skin, avoid rashes and for the child to be blessed with luck for the rest of the its life.

The role of work

In many cultures in East Africa, children, especially those in rural settings, carry the responsibility of fetching water from the well and collecting firewood. They take care of their younger siblings, are in charge of washing dishes, and helping with cooking. Children may also be involved in the cultivation of both cash and food crops. They will be allowed to play only after the parents are satisfied with the work done. However, it is important to note that there are gender differences particularly in the allocation of domestic chores. Girls are normally assigned chores like cooking and taking care of children while boys are more likely to be expected to do chores like slashing the compound.

Discipline and behaviour

It is the duty of children to wait on elders, and not the elders on children.

It’s a bad child who does not take advice.

If children in Africa openly oppose or question adult opinion, they are considered ‘bad mannered’. They are not allowed to be involved in decisions that concern them, and cannot say no to instructions. Most African communities view the husband as the head of the household who is responsible for making all decisions on behalf of the women and children. Some consider that corporal punishment is the right of parents and that they should not ‘spare the rod and spoil the child’. In many African cultures, children, especially girls, are supposed to be ‘humble’, and are not expected to express their feelings, talk out openly, or oppose adult ideas. Children who do so are considered rebellious or disrespectful.

Education

Basic formal education is compulsory throughout East Africa. In Kenya, for example, all children of primary and secondary school age are entitled to education. However, although there is growing recognition of the importance of formal education within the region, it does create some challenges for children. Many children are still not in school, especially those from poor families. Girls are less likely to attend secondary school, as are children with disabilities. Most children in rural settings walk long distances to school. Many children have to walk to school without adult protection, which often puts them at risk of abduction or sexual assault. Some children go to primary boarding schools from the age of six, which results in separation from their parents as they spend nine months of the year at school and only about three months at home.

The growing importance of education is contributing to a diminished role for community elders who traditionally held a significant role in providing guidance and wisdom. This erosion is being compounded by the internet and social media, which are becoming major sources of information for children, leading to a reduced level of influence by families and local community members.

Responsibility for children

In East African societies, a child traditionally belonged to the community rather than to individual parents. Children, therefore, were a shared responsibility. This meant that many aspects of the child’s training and learning, including, for example, communication about sexual reproductive issues, were the responsibility not only of parents, but also of aunts, uncles and grandparents. However, with changes in familial settings and society today, raising children is more often the responsibility of parents alone. This can create challenges, as they are often too busy to have time for their children. There are increasing rates of parental separation and divorce, and parenting traditions are also eroding. Some children are looked after by house girls who are themselves often very young; others are put in day care centres.

All these factors are having an impact on children’s social, physical, social, emotional and moral development.

Activity 1.3: Childhood in East Africa

- List three aspects of childhood that are common in East Africa.

- List three differences in the way girls and boys are treated in your culture.

- Describe three changes in East African society that are having an impact on the way children grow up.

This activity should take approximately 10–15 minutes.

Compare your own answers with the suggestions at the end of the study session.

1.5 Characteristics of childhood

As you can see from this study session so far, our understanding of childhood varies significantly from country to country and culture to culture. Similarly, our understanding of what children need in order to experience fulfilling childhoods and to grow up healthy varies across cultures. No universal consensus can be found as to what children need for their optimum development, what environments best provide for those needs, and what form and level of protection is appropriate for children at any specific age. These definitions are influenced by personal experience, working practices, local knowledge, law, and cultural influence.

As you consider characteristics of children, you need to recognise that every child is unique and special in its own way. There are, however, some common characteristics of the period of childhood, which should guide you in the way you look at and work with children. Three of the most important are: dependency, vulnerability, and resilience.

Definitions

Dependency: having a need for the support of something or someone in order to continue existing or to thrive.

Vulnerability: being more easily physically, emotionally, or mentally hurt, influenced, or attacked.

Resilience: the process of adapting well in the face of adversity, trauma, tragedy, threats or significant sources of stress.

It is important to recognise that these three characteristics are influenced by both external and internal factors. Children do not just acquire competencies and skills according to pre-determined biological or psychological forces. Of equal significance are environmental factors and the ability of children to make an active contribution to their social environments. And, of course, childhood is not a uniform period. A 17-year-old has profoundly different needs and capacities from a 6-month-old baby.

1.6 Dependency

Children start life as dependent beings that are totally reliant on others for survival, well-being and guidance. They need to grow towards independence. For example, babies need someone to feed them; a school-going child will need financial and moral support to access education. But as they develop, they become more independent. Such nurture is ideally found in adults in children’s families, but when primary caregivers cannot meet children’s needs, it is up to society to fill the gap.

This is a gradual process that is influenced both by the biological changes taking place, and also the social, cultural, economic and political environment in which the child is living. Children may have many responsibilities put upon them at a young age. As children grow up and acquire both the capacity and the desire to take greater responsibility for themselves, they seek greater autonomy and more involvement in decisions affecting them. This process of gradual development and emergence from dependency is known as the child’s evolving capacities.

1.7 Vulnerability

The fact that children are still developing means they are especially vulnerable to harm. For example, they are more at risk than adults from poverty, inadequate health care, poor nutrition, unsafe water, inadequate housing, environmental pollution or violence. Because of this vulnerability, adults have responsibilities to provide appropriate protection to ensure their safety and well-being. This includes parents and other caregivers, professionals working with children, and local communities as well as governments.

The degree of vulnerability for each child varies according to the age of the child, their individual characteristics and the circumstances they live in. For example, a teenager who is visually impaired is at a higher risk of rape than a teenager who is not. Very young children are particularly vulnerable when they are sick because their small bodies will dehydrate very quickly. Children, especially girls, can be vulnerable to rape, child labour and other forms of abuse because of their living environment. Children living in slums may be particularly vulnerable to poor hygiene and sanitation, pollution, and exposure to violence. The culture of silence and secrecy surrounding sexuality in many African cultures exposes children to sexual abuse, and poor management of body changes.

1.8 Resilience

Although children are both more dependent and more vulnerable than adults, they can display resilience in the face of adversity, risks and challenges, such as family problems, serious health problems, or workplace and financial stresses. In other words, children are not simply passive victims of what happens to them. They can exert influence and shape their own lives. It means that children are not always overwhelmed when they experience hardship but can recover or bounce back. Children do not all react in the same way to traumatic and stressful life events. A number of factors contribute to resilience. Children are most likely to display resilience if they have caring and supportive relationships within and outside the family. These relationships can offer love and trust, provide role models, and provide encouragement and reassurance. A child’s culture might also have an impact on how he or she deals with adversity. Resilience is not only influenced by the characteristics of a child (including age, temperament, sense of humour, reasoning, sense of purpose, belief in a bright future, and spirituality) it also involves behaviours, thoughts and actions that can be learned and developed by any child.

Children’s individual responses to adversity can be understood in terms of ‘risk’ as well as ‘resilience’. Risk refers to factors in a child’s life that mean they are more likely to suffer harm. Risks might include poverty or war, harassment and abuse, neglect and parental problems, all of which inhibit a child’s healthy development.

As a health worker, it is important to be sensitive to all these characteristics of children. You need not only to understand and respond appropriately to children’s vulnerabilities and to their evolving capacities, but also to recognise the competencies, skills and strengths they bring to their own lives and to the decisions that affect them. The following study sessions will look in more detail at the particular needs of children at different ages, and how those needs are recognised as rights of children.

Activity 1.4: Dependency, vulnerability and resilience in African childhoods

- To what extent do you think that these children are recognised as dependent?

- To what extent do you feel they are vulnerable? What harm might they be at risk of in their daily lives?

- What factors might result in these children having resilience to protect themselves against the risks they might experience?

Compare your own answers with the suggestions at the end of the study session.

1.9 Summary

This session was designed to introduce you to ideas about children and childhood, and to enable you to examine some of your attitudes towards children and childhood. In the session, you have learned that:

- International agreements and national law state that a child is a person up to the age of 18. In practice, the definition of a child varies significantly across different cultures. Economic, social and cultural factors all contribute to how different communities define who is a child.

Accepted cultural practices around childhood can be important and positive but this should not be taken for granted. Some practices may be harmful to children, and practitioners such as health workers should be prepared to see what is in the best interest of children.

- The period of childhood is treated very differently in different cultures. In East Africa, traditionally it has been viewed as a period of training for adulthood, although that is beginning to change as more children are in formal education. It is now increasingly viewed as a period of extended dependency in which children are entitled to protection.

- Childhood is characterised initially by dependency and vulnerability, but as children grow up they become less dependent and strive for greater autonomy. They gradually develop the capacity to contribute to decisions that affect them, and to contribute actively to their social environments.

- Children are not passive victims of risk and harm. They can acquire resilience to deal with adversity. Factors that contribute to resilience include being healthy, growing up in loving families, and safe communities.

1.10 Self-assessment questions

Question 1.1

What is the definition of a child?

Question 1.2

List three characteristics of childhood.

Question 1.3

Why do health practitioners need to re-evaluate their understanding of childhood? Identify one thing that has made you question your views of children and childhood.

1.11 Answers to activities

Activity 1.3: Childhood in East Africa

- Some possible issues you could have listed include: ritualised circumcision ceremonies for boys; shared responsibility for children across communities; expectations that children will obey their elders; widespread use of corporal punishment to impose discipline; importance attached to naming ceremonies.

- Some possible differences include: expectations that girls will play a considerable role in contributing to domestic chores and child care; boys being responsible for herding the cattle; differences in the rites of passages towards adulthood for girls and boys; greater freedoms for boys than for girls; girls being married at an earlier age than boys.

- Changes that are taking place in childhoods across East Africa might include: more children now attending school; greater access to alternative sources of information and aspiration through the internet and social media, leading to reduced influence of family and communities; weakening of the status of elders in the community.

These changing understandings and experiences of childhood are important to be aware of. They have significant influence on how adults treat children and how children respond. As a health worker, you need to be aware of and think about how your personal experiences, culture, religion, context and beliefs shape your view and treatment of children. Some of your views may be in children’s best interests while others may not. Questioning your own assumptions and attitudes can help you work out whether your personal views and decisions are promoting or neglecting a child’s well-being. They will affect, for example, how you as a health worker respond to a child who refuses treatment, who requests contraception or an HIV test, or who wants to have a say in the choice of treatment.

Activity 1.4: Dependence, vulnerability and resilience in African childhoods

- Neither the boys nor the girls in the photographs are recognised as fully dependent. Indeed, they are contributing to their families or communities in different ways. The girls are taking responsibility for the care of younger siblings. The boy and girl are working on the land, contributing to the local agricultural economy. However, it is also possible that these children are also acknowledged as dependents within their families and provided with the care, food, shelter and emotional support they need. They may also be attending school when not contributing to their families. By sending their children to school, parents or caregivers are acknowledging their status as children, entitled to an education and to be provided with the necessary care and support to enable them to access that education.

- The children may be vulnerable to harm if they are expected to undertake demanding work that is damaging to their health and well-being or interfering with their right to education. It is not the expectation that they contribute to the family economy that is in itself harmful. It is the extent of that expectation and its impact on the child that can render them vulnerable to harm. Children’s bodies are less developed than those of adults and they need more rest, more sleep and less strenuous physical demands. They are, for example, more vulnerable to the chemicals or pesticides that may be used in farming. In addition, children need and are entitled to have the opportunity to play. This is a very important part of their childhood and their development. Apart from attending school they need to have time for homework and to get sufficient rest and sleep to enable them to study effectively. If the hours they are expected to work are too high, and the nature of that work is too onerous, children will be vulnerable to harm.

Many factors may contribute to children’s resilience. They may be living in loving and caring families, and supported by a stable and cohesive local community. For many children, working with their families and taking responsibility for younger siblings can provide them with a strong sense of self-esteem. This is particularly the case where their contribution is highly valued within their local community. Factors that might mitigate against resilience would be, for instance, if girls felt their contribution was less valued than that of boys, if their participation in the work was overshadowed by threats of violence, or if their health was being damaged by their participation.

In other words, it is not the activity of working as a child that contributes to children’s vulnerability or resilience. It is the context in which it takes place that determines whether it constitutes a risk to the child or serves to enhance its well-being. Factors such as the hours worked, its perceived value to the community, the opportunities allowed for education and play, and the overall care and protection of the child will all influence vulnerability and resilience.

2 Child development

Focus question

What are the different stages of child development and how are they influenced?

Key words: benchmarks, development, evolving capacities, milestones, well-being

2.1 Introduction

In session 1 of this module, you explored how a child is defined in different cultures and how childhood is understood. In this session we will explore in more detail the different stages of development that a child goes through as they mature from birth to 18 years. Childhood is a period of very rapid development. Although there is growing acceptance internationally that childhood lasts until a child is 18 years old, obviously the capacities of a small baby are very different from those of a 17-year-old. The session will examine the different stages of children’s growth and development. It will also explore the fact that, although all children pass through common processes of development, the ages at which children develop different capacities is informed not just by biological and physiological factors. Social, cultural, economic and individual factors also play a significant role in determining how well children are able to grow up. The session will provide guidance as to what to expect of children at different ages, and explore your role as a health professional in supporting children’s development.

2.2 Learning outcomes

At the end of this study session, you will be able to:

- define and use correctly all of the key words

- describe the major stages and characteristics of child development

- describe the factors that influence child development

- apply your understanding of child development to your role as a health worker.

2.3 Recognise why an understanding of child development is relevant and important for health workers

When do you think a child should:

- Start walking?

- Say their first words?

- Dress themselves?

- Make friends with other children?

We will come back to these questions later in the session.

2.4 Why understanding stages of child development is important

From the moment of birth, a baby is in the process of extraordinarily rapid growth and development. As they grow up, children develop many different capacities. These capacities influence how they communicate, make decisions, exercise judgement, absorb and evaluate information, take responsibility, and show empathy and awareness of others. It is recognised in all societies that there is a period of childhood during which children’s capacities are perceived as developing or evolving rather than developed or evolved. When babies are born, they are completely dependent on their caregivers for food, warmth, shelter, cleanliness, and protection from harm. Nevertheless, even small babies are capable of communicating their needs. Through crying, facial expressions, body language, eye contact, they are able to engage with those caring for them, and to convey their feelings, moods and needs. As children grow up they gradually acquire an increasing range of capacities and skills and are able to take increasing control over their own needs.

As a health worker it is important to have some understanding of this process of children’s development. This will enable you to assess whether or not a child is developing appropriately, to understand what they are and are not capable of doing, and to respond to each child’s needs and rights more effectively.

Activity 2.1: Different aspects of development

Children develop in many different ways throughout their childhood. Can you describe what you think each of the following types of development mean? These terms will be used throughout this study session, so it is important that you understand them.

- cognitive development

- social development

- emotional development

- physical development.

Discussion

Aspects of development are all inter-linked, but they can each be understood in the following way:

- Cognitive development is the development of intelligence, conscious thought, and problem-solving ability that begins in infancy. Children actively learn by gathering, sorting, and processing information from around them, and then using that information to develop perception and thinking skills. Cognitive development refers to how a child perceives, thinks, and gains understanding of his or her world. Much of children’s formal education is concerned with promoting their cognitive development.

- Social development refers to the development of social skills and empathy that are needed to help children make relationships with other people. In order to develop socially, children need to be able to relate to their peers and adults in a socially acceptable way. Developing good social skills is necessary for them to be able to eventually form healthy relationships and fit into their community. Good relationships with parents are the building blocks for healthy social development in children. By giving lots of love and attention to a baby, parents form a close bond with the child, allowing him or her to grow in a comfortable, secure and socially healthy atmosphere.

- Emotional development refers to a child’s increasing awareness and control of their feelings and how they react to these feelings in a given situation. It provides children with the capabilities and skills that they need to function and survive in the society as well as the world. Children who have strong emotional development are more likely to be able to deal with things that go wrong or are challenging. Childhood is the critical age in the development of emotions. Those who have predominantly positive or happy memories of childhood will be better adjusted as adolescents and adults than those whose memories centre round unhappy experiences.

- Physical development can be defined as the progress of a child’s control over his or her own body. This includes control over muscles, physical coordination, and the ability to sit or stand. Physical development starts in human infancy and continues into late adolescent. The peak of physical development happens in childhood and is therefore a crucial time for neurological brain development and body coordination to encourage specific activities such as grasping, writing, crawling, and walking. As a child learns what their bodies can do, they gain self-confidence, promoting social and emotional development. Physical activities geared toward aiding physical development contribute significantly to a person’s health and well-being.

2.5 The different stages of development

The first two years

From birth through to the second year of life is the fastest period of a child’s development. During this time, there are a number of major milestones that children pass through as they achieve new skills and competencies. Although it is possible to provide a general guide as to when these milestones are reached, you need to recognise that every child is different, and will not necessarily progress at exactly the same speed. Many factors will influence the child’s development. Children need emotional warmth and stability, freedom from hunger, and a safe and secure environment in which to learn and to be stimulated, with opportunities to explore and discover. If these needs are not met, the child’s development can suffer.

Physical milestones

- At birth a child cannot engage in purposeful activities.

- By 3 months, babies can usually raise their head and chest if they are lying on their stomach and they can deliberately open and close their hands.

- Between 4–7 months, they start to roll over.

- Between 8–12 months, they start crawling and begin to walk around the 1-year mark.

- By 2 years old, a child is likely to be able to walk unassisted, run and climb with some assistance. They should also be able to play with objects around them depending on the environment they are in.

Cognitive milestones

- Babies begin to develop abilities to think and reason during this period.

- By the age of 2, most children can sort objects by basic shapes and colours if they are encouraged to do so.

- By the age of 2, they have the ability to begin pretend or imaginative play. They start to understand simple cause-and-effect principles, such as the fact that a stone falls to the ground if you let go of it.

- They also begin to understand that something still exists even if they can’t see it.

Social milestones

- When babies are born, they very quickly begin to recognise and respond to their primary caregivers.

- By 12 months, they can explore objects such as toys (if they have them) with others.

- Although by the time they are 2 years old, they will play alongside other children, they will not yet engage more directly in social forms of play or interaction.

Emotional milestones

- By 12 months, most infants are able to observe and react to other people’s emotions.

- By the time they are approaching 2 years old, children begin to understand and assert a sense of self. This milestone often results in the toddler’s answer of ‘no’ to a request to do something.

- If parents encourage them, 2-year-olds can also name basic emotions, such as ‘happy’ and ‘sad’, and point them out when they see them.

Language milestones

- From shortly after birth to around one year, a baby will begin to make speech sounds.

- At around 2 months, the baby will engage in cooing, which mostly consists of vowel sounds.

- At around 4 months, cooing turns into babbling that consists of repetitive consonant–vowel combinations.

- It is important to recognise that babies understand more than they are able to say. At around 1 year old, many babies will begin to say simple words, and express wants and needs by pointing to objects.

- By the age of 2, they will be able to put two to three words into phrases.

The pre-school years

The period between 2–5 years is a period of discovery and emerging independence for children when they will begin to explore new forms of play and new environments. As with babies, children do not all develop at exactly the same rate, but there are some benchmarks that provide a general guideline of when children will acquire new capacities, behaviours and skills. It is probably less helpful to describe these processes as milestones as they happen more gradually than in the first two years of life.

Physical development

- Children during this period are gaining significant strength and coordination.

- They are more able to control their use of their of hands and fingers. For example, they can dress themselves, tie a bow and do up a button.

- They acquire skills such as jumping, hopping and skipping.

- If children have the opportunity, they can start to cut with scissors, paint and draw.

Cognitive development

- 2–5-year-olds are very curious.

- They are beginning to explore the cause and effect between actions and events.

- They have the ability to start to recognise letters and numbers, colours, shapes and textures.

- Their memory skills increase.

- They become more aware of things that are alike and different.

Emotional and social development

- Children start to demonstrate affection and intense feelings of fear, joy, anger and love.

- They are also able to develop a sense of humour.

- Many children enjoy showing off and demand attention.

- Children are beginning to be more aware of themselves and others.

- They are more independent, and more able to share and take turns, develop friendships and show respect for others’ things.

Communication

- Between 2–5 years, children’s language develops, vocabulary will expand rapidly and they will begin to engage in more complex conversations.

- Children begin to engage in a wider social circle.

- They begin to ask questions during this period – why, what, who?

- They will start to learn the correct grammar for their language.

- They develop improved listening skills.

Middle childhood 6–10 years

Progress during the ages of 6–10 years in the major areas of development is more gradual than in the first few years of life.

Physical development

- Children aged 6 to 10 are more independent and physically active than they were in the pre-school years.

- Strength and muscle coordination improve rapidly in these years.

- Many children learn to throw, hit or kick a ball.

- Some children may even develop skills in more complex activities, such as dancing.

Cognitive development

- Children develop a more mature and logical way of thinking. If encouraged, they become able to consider a problem or situation from different perspectives.

- However, they are most concerned with things that are ‘real’. For example, actually touching the fur of an animal means more to a child than being told that an object is ‘soft like an animal’.

- Because they still can mostly consider only one part of a situation or perspective at a time, children of this age have difficulty fully understanding how things are connected.

Social and emotional development

- Children begin to be more separate from parents and seek acceptance from teachers, other adults, and peers.

- Children develop the ability to judge themselves and be aware of how others see them. For the first time, they are judged according to their ability to produce socially valued outputs, such as getting good marks in school.

- Children come under pressure to conform to the style and ideals of the peer group.

Adolescence

Between 11 and 18 years of age, young people undergo rapid changes in body structure and physiological, psychological and social functioning. Growing research on the adolescent brain has provided a better understanding of typical adolescent development. Even though changes in puberty follow a predictable sequence, there is a great deal of variation between adolescents, in both the timing of changes and the quality of the experience. Hormones are the primary influence during these years and enable the transition from childhood to adulthood. However, gender as well as the life experiences of the child will affect their development – what kind of family and community they live in, the attitudes of people around them, whether they are living in poverty or a more affluent family.

Physical changes

- Children undergo puberty with increases in body hair, breast development and onset of menstruation in girls, and testicular growth and deepening voice in boys.

- These developments are also associated with an emerging interest in sexual activity.

- Adolescents also tend to gain significantly in height and weight during this period.

Cognitive development

- Adolescents acquire a capacity for abstract thought, expand their intellectual interests, and engage in more complex moral thinking and reasoning.

- They develop the ability to think through the consequences of their actions.

- They have increasing capacity to make decisions and act with a sense of the subsequent implications.

Social and emotional development

- Adolescents often struggle with a sense of identity, experience self doubt, worry about themselves and about whether they are normal.

- The peer group becomes more important to them and can place an increasingly influential role on their lives.

- They want greater independence and this often gives rise to conflict with parents or guardians.

- Adolescents are sometimes moody and disengaged and will test out boundaries. It is also a period of a desire for greater privacy.

2.6 Understanding stages of development

Activity 2.2: Understanding stages of development

- Look at the following list of activities and developments and place each one in the appropriate column in the table below.

- Still think in concrete terms

- Become increasingly separate from parents and seek acceptance from teachers

- Become more involved with friends

- More able to control the use of their hands and fingers

- Sometimes moody and disengaged

- Begin to recognise and respond to their primary caregivers

- Begin to understand and assert a sense of self

- Cannot engage in purposeful activities

- Able to consider several parts to a problem or situation

- Start to roll over from their back to their front

- Recognise letters and numbers, colours, shapes and textures

- Have an emerging interest in sexual activity

- Begin to ask questions – why, what, who?

- Able to put 2–3 words into phrases

- Struggle with a sense of identity

- Feel under pressure to conform to the style and ideals of the peer group

- Desire for greater privacy

- Not yet able to engage more directly in social forms of play or interaction

- Acquire a capacity for abstract thought

- Develop a sense of humour

- Develop the ability to think through the consequences of their actions

- Peer group can place an increasingly influential role on their lives

| 0–2 years | 2–5 years | 6–10 years | Adolescence |

|---|---|---|---|

- List three ways in which you think the relationship between a child and his or her parents will change during adolescence.

When you have finished the activity, compare your answers with those at the end of the study session.

Activity 2.3: Case study

Samuel is a 2-year-old boy who lives with his grandmother. His mother passed away when Samuel was 3 months old. Samuel started to support his head and sit unsupported at the age of 6 months. His grandmother started to feed him a supplementary diet to make sure he doesn’t go through nutritional deficiency and end up being malnourished. Samuel started to crawl at 9 months and still crawls at the age of 2 years. Samuel has not yet started to walk, and he doesn’t speak any words. His grandmother knows he’s hungry whenever he cries out loud continuously, since he doesn’t point at food when he wants to eat. She is worried about his developmental progress since she has had experience raising Samuel’s mother. So she decides to take him to a nearby health facility.

Imagine you are the health care provider at the health facility. Try to identify the normal and delayed developments of 2-year-old Samuel.

Compare your answers with the discussion at the end.

Discussion

A number of factors in Samuel’s development might give you cause for concern. His early development appeared to be normal. His ability to sit up unaided and to start crawling were well within the ‘normal’ age range for these activities. However, the fact that he is still crawling at 2 years old might indicate he does have some problem with his mobility. In addition, his failure as yet to begin to form any words might also be a worry, although children’s language development can vary significantly from child to child. It would be helpful to know if he understands words but is not yet using them. You might ask his grandmother how much she talks to Samuel and how he responds. His failure to point to food or show any means of communicating hunger other than crying may indicate that he is not yet able to make the link between hunger and food. Given these concerns, it would be important as soon as possible to get Samuel further assessed to find out more about both his movement and mobility and his communication. He might need referring to a local hospital where there are specialists who can assess, for example, his speech, his muscular development, his hearing, and his cognitive development. The sooner a diagnosis is made, the more likely it will be that he can get the necessary support and help to encourage his proper development.

2.7 Promoting children’s evolving capacities

We have learned that it is possible to identify broad patterns of development that take place across given age spans. However, children’s evolving capacities are significantly affected by their particular experiences. As you saw in Study Session 1, the process of gradual development and emergence from dependency is known as the child’s evolving capacities. There is growing recognition that children’s development is not a pre-determined process that takes place automatically. Rather it is a cultural process, which is affected by the social, economic and cultural factors in the life of the child, as well as the opportunities available to them.

What do we mean by social, cultural and economic factors?

Social factors – these are things like how the family, the local community, and daily life is organised. For example, who looks after children? Is there a large extended family support system? Who does what tasks?

Cultural factors – these are the attitudes and values in a family and community – the way they bring up children, the type of discipline used, how children are expected to behave, attitudes towards education and play.

Economic factors – these relate to how poor or well-off a family is, what kind of housing they have, the sort of work they do, the level of education the parents have.

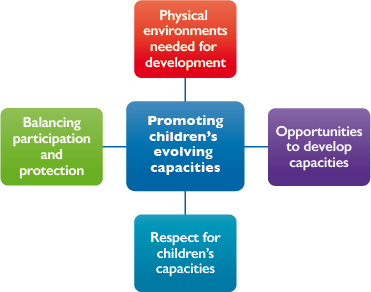

It is necessary to build an understanding of what factors are known to have a positive or negative influence on children’s lives, and which contribute to their development or evolving capacities (see Figure 2.1).

2.8 Creating the necessary physical environments for children to thrive

Children are entitled to grow up to reach their optimum development. Adults, therefore, have a responsibility to create the necessary environments to enable this to happen. This involves not only parents, but also professionals such as teachers and health workers, local communities, and governments. But what does this look like?

Without access to basic standards of physical care and provision – such as food, shelter, clothing, health care, and clean environments – children’s development will suffer. Many physical and intellectual disabilities are linked with material factors such as poor diet, environmental pollution, and exposure to risk of accidents, and are made worse by inadequate access to health care. For example, iodine deficiency in pregnant women can lead to severe intellectual disabilities in children. Pre-natal and post-natal health care as well as health care for children in general is important for their development.

2.9 Creating the opportunities for development of children’s capacities

Family life

Children are most likely to thrive if they are brought up in a family environment and an atmosphere of happiness, love and understanding. The family is the group in society most capable and responsible for meeting the needs of children. Families in different cultures can take many different forms, and they can all provide quality care for their children. In Africa, for example, it is often argued that it takes a village to bring up a child, but the importance of stability and the need to be loved and valued are universally accepted for children in all cultures. There is growing evidence of a direct relationship between children’s development outcomes and the quality of care they receive.

Education

Education should provide all children, including those with disabilities, with the opportunities to develop optimum levels of competence to be able to play a full part in their society, as well as to achieve their personal ambitions. However, the actual experience of education for many children is very different. Schools often fail to provide an effective learning environment. They are often authoritarian, poorly managed, inadequately resourced or offer a curriculum that is irrelevant to children’s lives. Many schools are too focused on testing and exams. Research evidence compiled by the Africa Child Policy Forum, a pan-African organisation, also paints a bleak picture as to the levels of violence perpetrated against children, particularly girls, both within schools and when travelling to school. Too often, children are beaten, threatened and humiliated by teachers. Girls may be sexually violated or faced with demands from teachers for sex in return for grades. Children cannot learn effectively in abusive environments (ACPF, 2001).

Play

Play is essential to the health and well-being of children. They learn through play. In addition, play:

- promotes creativity, imagination and self-confidence

- contributes to children’s physical health

- builds social skills

- provides fun and pleasure

- contributes to building children’s capacities to negotiate, achieve emotional stability, resolve conflicts, and make decisions

- enables children to explore the world around them, experiment with new ideas, roles, and experiences.

So, you can see that it is a very important part of children’s development. However, many children are denied the opportunity for play. Parents and teachers often fail to recognise the importance of play in children’s lives and view it as time being wasted. Many children with disabilities are denied any real chance for play as a result of discrimination, social exclusion and the physical barriers imposed by the environment. Girls, in particular, are denied chances to play because of the burden of domestic work that falls on them. Excessive formal demands on children’s time, whether through paid employment or long hours spent at school and doing homework, can also deny children the chance to play.

Activity 2.4: Understanding the factors that help or hinder children’s development

Think about the children in your local community and their opportunities for play. Then answer the following questions:

- Did you have a chance to play when you were a child?

- What attitudes do parents and teachers have towards play?

- Do their attitudes change as children get older?

- Do parents and teachers have different attitudes to play for girls and for boys?

- If so, why do you think that is?

Compare your answers with the discussion at the end.

Discussion

You might have decided to ask friends, neighbours and colleagues about their attitudes to play. It is likely that they would have been more sympathetic to the importance of play among very young children and less so as children get older.

In many communities there is also a much greater acceptance of boys playing – football, swimming, hanging around. There tend to be far more demands on girls’ time as they are expected to contribute to domestic chores and care for younger siblings. Boys are allowed more freedom and autonomy. In other communities, such as the pastoral communities, boys are expected to take on herding responsibilities at a young age, but they may be able to combine play with work.

The type of work girls are doing can make it harder for them to integrate play into their chores. However, play and recreation is just as important for girls. They need time to be with their peers, and to have opportunities to structure their own activities.

Play takes different forms as children grow older – they spend less time in imaginative games and using toys. However, free time when they can choose for themselves who to be with and what to do, or indeed to choose to do nothing, is a vital part of their development.

2.10 Respecting children’s capacities to participate

There is a tendency across East Africa, as in other regions of the world, to deny children the opportunity to take responsibility for decisions and actions that they are competent to take. Children are expected to listen and do as they are told. They are not expected to contribute their own ideas, influence their own communities, or contribute to decision-making. Yet they are often capable of understanding and engagement far beyond the assumptions that adults have. For example, it is a common concern of children that health professionals fail to acknowledge their ability to be involved in decisions about their own health care. However, children should be encouraged to take responsibility and participate in those decisions and activities over which they do have competence. And like adults, children build competence and confidence through direct experience – doing things rather than just being told about them. It is a ‘virtuous circle’ – in other words, the more children participate the more skills they acquire and the better they are able to participate in the future. The more children are recognised and encouraged to be involved in decisions and take responsibility, the more they will acquire the capacities to do so effectively. For example, you can actively engage children and young people in discussions about how to protect themselves from infection, managing pain relief, approaches to sexual health or how to change dressings.

2.11 Balancing participation and protection

Although it is important to respect children’s capacities to take responsibility for their own lives, it is also important to recognise that children are still developing and that they are entitled to protection to ensure they are not forced to take on adult responsibilities too early. No universal rules exist to determine what level of protection children need at any given age or stage of development. Indeed, if you look at the situations to which children are exposed in different cultures, you will see that it varies widely indeed. These differences highlight the fact that, to a large extent, children develop capacities to cope with challenging situations in accordance with the opportunities they are given and the expectations placed upon them.

Differences in protection in different cultures

The nature and extent of care seen as necessary by parents varies widely according to cultural, economic and historical factors. For example, children in fishing villages in South East Asia are actively encouraged to take part in survival strategies that build up their strength. Children in the Arctic are taught survival strategies by experimenting with uncertainty and danger in order that they acquire the skills necessary to cope with problems as they arise. Boys in pastoral communities in East Africa are expected from a very young age to tend to cattle and goats on their own. However, in most European countries, young children are not expected to go out alone. They are taken to school by their parents, and are not left alone at home without adult supervision. In other words, the expectation that children will take care of themselves or younger siblings is considered normal and functional in many societies, but dangerous and neglectful in others.

There is no simple way to decide the levels of protection needed by children or to decide the most effective means of providing protection. Respect for children’s evolving capacity to take responsibility for decision-making must be balanced against their relative lack of experience, the risks encountered, and the potential for exploitation and abuse. It is also important to recognise that protection is not just a one-way process, with adults as protectors and children as recipients. The reality is more complex: children can contribute significantly to their own and other children’s protection.

Case study: Children protecting others

In West Africa, a network of children and young people has been established to explore ways of building safer and more protective environments across the region. They are developing practical ideas on how to support each other to challenge violence and reduce the levels of physical and sexual violence against children.

For example, they observed that children with disabilities in rural communities were particularly at risk of sexual assault during the daytime. Parents were at work in the fields and their brothers and sisters were at school. They are often left alone in their hut. During this time, there was a high incidence of men approaching the children and raping them. Children with disabilities find it difficult to defend themselves, for example, if they are deaf/mute, they may not be able to scream and if they have mobility impairments, they cannot run away.

The children in the network decided to provide the children with disabilities with a mobile phone with a number to text which will alert someone who can then call the police, alert the resident magistrate or the child protection committee. In this way, children are finding solutions to violence and ensuring that the responsible adults are aware of the problem and encouraged to take the necessary action.

The extent to which children are likely to be at risk of harm from any potential activity or situation will be affected by a number of factors:

- Whether the expectations of children are widely similar within the community – for example, in a society where all girls are expected to undertake child care responsibilities from an early age, or where young boys or girls are expected work on the land, the negative impacts on the child are likely to be far less than if this was being demanded of a child in a society where this was not normally expected. However, this needs to be balanced against the harm that might be caused by denying girls or boys opportunities for education and play.

- Level of support provided by the key adults in the child’s life – for example, where parents provide appropriate and positive guidance and encouragement to support the child’s engagement in a particular activity and help a child to learn from its mistakes, rather than using threats and punishment.

- Degree of control experienced by the child in coping with the situation – for example, if children feel they are in control of a situation, and can make informed choices about what they are able to undertake and how, this will help them feel confident and better able to cope in the future.

- Child’s personality and strengths – the child’s individual personality will influence how much responsibility he or she can take. Children who are healthy, strong, self-confident and with high self-esteem can cope better with adversity and challenges.

Activity 2.5: Balancing protection and participation

Imagine you have a 13-year-old daughter. Think about the activities she increasingly wants to engage in and your concerns about her safety and protection. List all the issues you need to think about in trying to balance her growing need for independence with her continuing need for protection.

Compare your answers with the discussion below.

Discussion

The challenge for parents is trying to assess what level of independence is appropriate as children grow up. Obviously, the levels of protection will decrease as the child gets older, but the question is how much autonomy is appropriate and at what ages. There are a number of factors to take into account in making those decisions:

| The case for protection | The case for more independence |

|---|---|

| If you do not provide consistent boundaries with reasons for imposing them, children can become insecure. They do not have guidelines on what is expected of them. | If you over-protect children, they do not get the chance to start learning how to make their own decisions and choices. Gaining these skills will give them confidence and ability to make informed choices and take responsibility for their own protection. |

| Children may think they know more than they do. This may mean they take risks without understanding the consequences. | If children are subservient, and not used to making choices or challenging adult authority, they may be more vulnerable to abuse and exploitation by adults. |

Parents do have experience and knowledge that can be used to make informed assessments of potential risks. | Giving children appropriate information is a key to promoting their protection, and helping them make safe and appropriate choices. If you just say no, and don’t help them make decisions for themselves, you are denying them the chance to learn and begin to make safe choices for themselves. |

2.12 Summary

- Child development consists of a range of different types of development – all are important and interlinked.

- Every child should have the opportunity for the fullest possible cognitive, social, emotional and physical development. This requires that the needs of children are supported and fulfilled, both in terms of their well-being at the present time and in terms of their future potential.

- Children go through stages of development that take place at roughly similar ages. It is important to understand these levels of development in order both to identify if the child is experiencing problems or not developing appropriately. Understanding these stages also helps adults to respond appropriately to children at given ages.

- Development is not a given. Many factors can contribute to or impede the extent to which children are able to develop to their optimum potential, for example:

- physical, psychological, social, economic, environmental and cultural factors, as well as the family, peers, community, society, and government

- children’s own individual capacities, context and culture, and their active involvement in decisions affecting their lives.

- One of the challenges for parents and caregivers is to balance the child’s right to take growing responsibilities for decisions affecting them as they develop with their continuing right for protection from harm. Over-protection of children denies them the opportunity to begin to understand risk and how to make safe choices. On the other hand, under-protection can expose children to dangers that they are not fully aware of or sufficiently experienced to handle.

2.13 Self-assessment questions

Question 2.1

Name four different aspects of development and describe them briefly.

Question 2.2

Describe three features of children’s development:

- in the first two years of life

- between the ages of 6–10 years

- in adolescence.

Question 2.3

Outline three of the key factors that affect how children develop.

Question 2.4

Describe why knowledge of child development is important for a health worker to understand.

2.14 Answers to activities

Activity 2.2: Understanding stages of development

- The developmental stages of children can be grouped as follows:

| 0–2 years | 2–5 years | 6–10 years | Adolescence |

|---|---|---|---|

Cannot engage in purposeful activities Start to roll over from their back to their front Able to put 2–3 words into phrases Not yet able to engage more directly in social forms of play or interaction Begin to recognise and respond to their primary caregivers | Recognise letters and numbers, colours, shapes and textures Begin to ask questions – why, what, who? More able to control the use of their of hands and fingers Develop a sense of humour | Begin to understand and assert a sense of self Able to consider several parts to a problem or situation Become increasingly separate from parents and seek acceptance from teachers Become more involved with friends Still think in concrete terms | Sometimes moody and disengaged Have an emerging interest in sexual activity Desire for greater privacy Peer group can place an increasingly influential role on their lives Struggle with a sense of identity Develop the ability to think through the consequences of their actions |

- Go back to the answers you gave to the questions at the beginning of this study session. How accurate were you?

- The possible changes in parental relationships might include:

- adolescents becoming more critical of parents

- desire for greater privacy

- more arguments over behaviour and boundaries

- adolescents becoming more aware of their parents and potentially having greater understanding

- parents giving adolescents more responsibilities

- greater difference in parental attitudes towards boys and girls

- adolescents wanting to spend more time with peers than family.

It is often felt that adolescence is a period of great tension between parents and adolescents. However, it is important to recognise that as adolescents acquire greater skills and capacities, they also can provide an increasing source of support to their parents, if parents are able and willing to acknowledge their children’s right to greater independence and ability to take on more responsibilities for their own decision-making. Adults need to learn to listen to adolescents without judging them.

3 Children’s needs and rights

Focus question

What is the relationship between children’s needs and children’s rights?

Key words: interdependence, needs, realisation, rights

3.1 Introduction

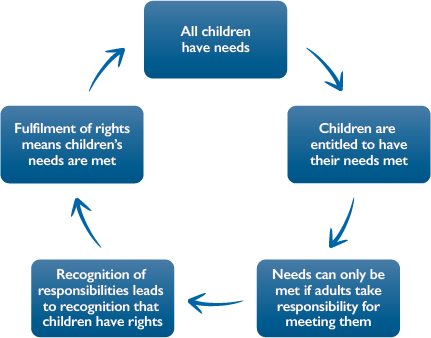

In Study Session 2 of this module, you will have learned about child development, and the stages that all children go through from the time of their birth to the time they reach adulthood. Children have needs that change over time, with age, maturity and experience. All societies recognise that children require nurturing and protection from harm in order to develop and grow as healthy people who are capable of reaching their full potential. Parents or guardians have the responsibility to ensure that children are adequately taken care of and enabled to thrive.

In this study session, we will look firstly at the needs that children have if they are to grow up healthily. It will focus both on those needs that are common to all children, and also how the fulfilment of those needs differs depending on a child’s age and other circumstances. We will also discuss how human rights, and children’s rights in particular, provide the basis for ensuring that these needs are met.

3.2 Learning outcomes

At the end of this study session, you will be able to:

- define and use correctly the key words above

- understand what needs children have

- recognise the importance of understanding how to meet children's needs in ways that are appropriate to their ages and abilities

- explain the relationship between children’s needs and children’s rights.

3.3 Understanding children’s needs

Activity 3.1: Parents’ hopes and aspirations for their children

Before starting this study session, imagine a baby has just been born in your family. Think about the hopes and aspirations the parents will have for that baby. If you are studying this session with others, discuss in a group and come up with a list of five things you think would be important. See if you can agree on the five most significant.

If you are studying alone, ask your family, friends and colleagues, and try and come up with five suggestions.

Discussion

Some of the following ideas may have come up in your discussions. Parents may want their child to:

- be born healthy

- be free of illness and disease

- be happy

- be responsible

- show self-discipline

- develop normally

- be hard-working

- succeed at school

- care for their family

- be obedient.

We will come back to this activity at the end of the session.

What is a need?

A need can be described as something that is necessary, very important, or essential for a person to live a healthy and productive life. Needs are different from wants. Wants are things that are desirable, but not necessary or essential. Children, for example, have a need for food, because without food, they will not grow or be healthy, will be unable to learn well, work or play, and ultimately will die. People need food to survive. On the other hand, a person may want a particular type of food, preferring perhaps to have fish rather than vegetables. However, although they may want fish, they do not need fish to survive. Food is a ‘need’. Fish is a ‘want’.

Another way of distinguishing between needs and wants is that people have a limited number of needs. It is usually possible to identify all of a person’s needs, whereas people can have an infinite number of wants, which differ from person to person.

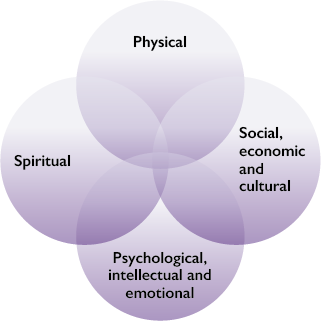

Human needs can be categorised in many different ways. Figure 3.1 shows one way of categorising them.

- Physical needs: shelter, health care, water and sanitation, protection from environmental pollution, adequate food, adequate clothing, and protection from violence, exploitation and abuse, exercise for strength-endurance-coordination, opportunities for development of physical skills.