Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Monday, 24 November 2025, 11:28 AM

Module 2: Module 2 - Children’s rights and the law

Introduction to Module 2

This is the second module in a course of five modules designed to provide health workers with a comprehensive introduction to children’s rights. While the modules can be studied separately, they are designed to build on each other in order.

Module 1: Childhood and children’s rights

Module 2: Children’s rights and the law

Module 3: Children’s rights in health practice

Module 4: Children’s rights in the wider environment: role of the health worker

Module 5: Children’s rights: planning, monitoring and evaluation

Module 2 provides you with an introduction to the legal basis for children’s rights. It is important to understand how the way of working in health care promoted in this course is supported by international agreements and national laws. The module comprises three study sessions, each designed to take approximately two hours to complete. The sessions provide you with a basic introduction to the subject and are supported by a range of activities to help you develop your understanding and knowledge. The activities are usually followed by a discussion of the topic, but in some cases the answers are at the end of the study session. Please compose your own answer before comparing it with the answer provided.

- Study Session 1 focuses on the international and regional conventions and agreements on children’s rights that all the countries of East Africa are signed up to. Specifically, you will find out about the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child and the African Charter on the Rights and Welfare of the Child. By the end of the session you will be familiar with many of the key sections of these important documents and have had the opportunity to think about how they apply to your work as a health practitioner.

- Study Session 2 builds on your knowledge of the international agreements and explores how their principles are translated into the national laws of each country. It is important to understand what rights children have and how the law protects those rights. The session focuses on four aspects of the law particularly relevant to health workers – the right to be cared for and looked after, the right to protection from violence and abuse, the right to information, and the right to be heard and involved in health care decisions. By the end of the session you will understand how to respect children’s rights in your day-to-day work, and how to recognise and take action if you see that their rights are not being respected by others.

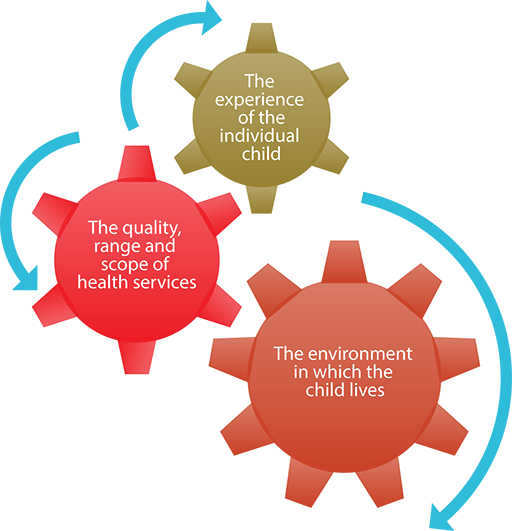

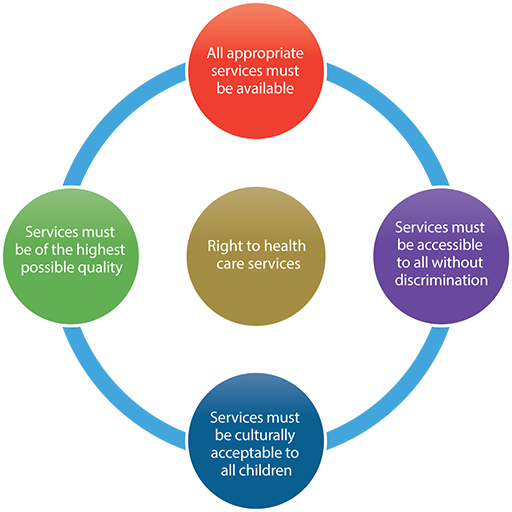

- Study Session 3 explores the meaning of the right to health. You will already have learned about the right to health alongside the whole range of children’s rights. However, understanding health in more detail is obviously important in your practice role. By the end of the session you will understand how the right to health is made up of many different elements. Some of these are about health care at your own facility, but the study session will also look at the wider issue of health care provision and the importance to children’s health of the social context; for example, the provision of clean water.

1 International and regional laws

Focus question

How do the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child and the African Charter on the Rights and Welfare of the Child ensure that children’s rights are protected?

Key words: Charter, Convention, guiding principles, primary duty bearer, ratification, responsibility

1.1 Introduction

In this study session you will learn about the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child and the African Charter on the Rights and Welfare of the Child. They are referred to as international legal instruments or treaties. They both outline a broad range of rights that children are entitled to. They promote a philosophy of dignity and respect for children, challenging traditional views that children are passive recipients of care and protection.

While the UN Convention applies to children throughout the world, the African Charter was drawn up to address the particular situation of children in Africa. Both treaties include a number of rights directly and indirectly relevant to health. Knowledge of all these rights is important for health workers. This session will explain the rights in the UN Convention and the African Charter and help you to understand their relevance for your work.

Study note

For ease in reading the text, from hereon we will be referring to the UN Convention and the African Charter.

1.2 Learning outcomes

When you have studied this session, you will be able to:

- define and use correctly all the key words used in this study session

- describe the key provisions contained in the UN Convention and the African Charter

- explain the four principles of the UN Convention and the African Charter

- describe the key differences and similarities between the UN Convention and the African Charter

- understand the relevance of the UN Convention and the African Charter to the health worker’s role.

1.3 United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child

The UN Convention is a comprehensive human rights treaty. It sets out minimum legal and ethical standards for all children, as well as goals to aspire to. In practice, the Convention is a vision for children, backed up by legal standards. It was drawn up in the UN by nearly all the countries of the world, including East African countries, because previous human rights conventions did not address the specific situation of children. The UN Convention was drafted to meet this lack of provision, and was adopted by the UN in 1989. It has now been ratified by nearly every country in the world: indeed, it is the most ratified international human rights convention in history.

The Convention:

- defines a child as a person below the age of 18 (unless majority is attained earlier)

- applies to all children without discrimination on any grounds

- identifies children as requiring measures of special protection and support

- recognises the importance of family, community and culture in the upbringing, protection and overall well-being of a child.

Understanding the terminology: a summary

What is a Convention?

A ‘Convention’ is a treaty or legal instrument – an agreement in international law between countries. The UN Convention on the Rights of the Child is a wide-ranging international treaty that contains some 40 ‘Articles’ defining the rights of children.

What is a Charter?

A ‘charter’ is another form of legal agreement between countries. The African Charter on the Rights and Welfare of the Child is an agreement between the countries on the African continent.

What are Rights?

Rights are the basic legal, social or ethical entitlements of any human being, including children; for example, the right to health or the right to protection from violence.

What are Articles?

Each right is described in more detail in the Convention in an individual section or paragraph; each of these descriptions is called an Article. For example, the right to health is found in Article 24 of the UN Convention. It contains many specific illustrations of what the right to health means and what governments must do to achieve it, such as reducing infant mortality and providing clean drinking water.

What is Ratification?

Ratification is the process by which an individual country signs up to the Convention and formally makes a commitment, under international law, to implement the Convention’s principles and standards. To date, 193 countries have ratified the Convention or officially committed to it through equivalent means. Somalia, South Sudan and the United States of America are the only countries that have not ratified the Convention. The African Charter has been ratified by 46 African countries, but 8 countries have yet to do so (ACERWC, n.d.).

Activity 1.1: What rights do children have?

Make a list of all the rights you think children have in your country.

Show your list to your colleagues at work and discuss the question of children’s rights with them. See if you can all agree on a list of rights.

Do you think these rights are met for all children in your country?

Discussion

There are many rights that you may have identified:

- Children have a right to survival, which would include, for example, the right to food, water, shelter and an adequate standard of living to enable their development.

- Children also have a right to optimum development, for which they need access to health care, play and education.

- Children have a right to protection from violence, discrimination and all forms of exploitation.

- Other rights that might seem less obvious concern the child having an identity – for example, the right to a name and a nationality, and the right to be registered at birth.

- Children have a right to family life. This means respecting families, providing them with support to enable parents to care for their children properly, and a child not being removed from their family unless this is in the child’s best interests.

- Children have the right to be treated fairly if they are accused of a crime.

- Finally, children have rights to have their own views, to be listened to and taken seriously, and to make decisions for themselves as they acquire the ability to do so – for example, decisions about their religion, their opinions and their friendships.

Have a look at the summary of the UN Convention, this should be available to you as a resource (if not, it is available in the resources section of the CREATE website), and see which rights you got correct and which other rights you could have suggested.

How far you think these rights are realised for children in your country will depend on which country you live in. Many other factors affect children’s lives: whether their parents are wealthy or poor, whether the child is a girl or a boy, whether they have a disability or not, whether they live in a town or in a rural community. For example, children with disabilities are less likely to be able to exercise their right to education. Adolescent girls are less likely to have the chance to experience the right to play. Poor children in isolated communities are less likely to have access to health care and the best possible health.

So your answers to the question may well depend on where your health facility or the community in which you work is located. However, it is important to remember that all rights apply to all children. All governments have a responsibility to make every effort to make sure that these rights become a reality.

1.4 The ‘3 Ps’

To help understand the UN Convention more easily, it is often divided into what are commonly called the ‘3 Ps’: these are the rights to Provision, Protection and Participation.

The Right to Provision

These are the rights to services, skills and resources: the ‘inputs’ that are necessary to ensure children's survival and development to their full potential; for example:

- health care (Article 24)

- education (Article 28)

- the right to play (Article 31).

The Right to Protection

These are the rights that ensure children are protected from acts of exploitation or abuse, in the main by adults or institutions, that threaten their dignity, their survival or their development; for example:

- protection from abuse and neglect (Article 19)

- the regulation of child labour (Article 32)

- protection and care in the best interests of the child (Article 3).

The Right to Participation

These are the rights that provide children with the means by which they can engage in those processes of change that will bring about the realisation of their rights, and prepare them for an active part in society. They include, for example:

- the right to express their views and to be heard in legal proceedings (Article 12)

- freedom of expression and the right to information (Article 13).

Activity 1.2: The 3 Ps

Look through the summary of the UN Convention, which you will find in the resources section of this website. Find two examples of a child’s right for each of the 3 Ps, other than the ones listed below.

| Category | Right | Article |

|---|---|---|

| Provision | For example: Health care | 24 |

|

| |

|

| |

| Protection | For example: Protection from abuse and neglect | 19 |

|

| |

|

| |

| Participation | For example: Right to information | 13 |

|

| |

|

|

Compare your answer with the one given at the end of the study session.

Activity 1.3: Health workers and a child’s rights

Look again at the list of Articles in the UN Convention. Identify three that you think are particularly important to the role of health workers, other than the right to health. Why are these Articles relevant?

Discussion

There are some very obvious rights that are relevant to the role of the health worker. Article 24, the right to the best possible health, is immediately relevant, as is Article 6, the right to life and development. However, there are other rights that are also very important:

Perhaps you noted in Article 7 that children ‘shall be registered immediately after birth’. Health workers can play an important part in informing mothers about a child’s right to birth registration, and why it is necessary. Birth registration ensures the identity of the child, which may be needed to get a place in school, to access health care or to get a passport. Registration is also important for governments: it gives them information about every child born so that they can plan services properly, taking into account accurate information on the size of the population.

Article 12 is also relevant as it says:

the child who is capable of forming his or her own views has the right to express those views freely in all matters affecting the child, the views of the child being given due weight in accordance with the age and maturity of the child.

This is clearly very important when you are discussing and considering health treatments. Children need to be involved in those matters and to be helped to make decisions about their own health care.

You may have thought Article 31 concerning engaging in play was not directly relevant to you. However, if we recognise play as important in children’s lives, we need to think about how a hospital or a clinic could provide a simple play area for children who have to stay there.

You may have identified lots of other examples, such as the rights of children with disabilities, the rights of children to protection from violence, the rights of children to have their best interests as a primary consideration. Many of these rights are relevant to all areas of a health worker’s role, not just the right to health, and they can help you to view all the different aspects of a child's life. You will learn more about the specific rights that are relevant for health workers in the next study session.

1.5 The interconnected and indivisible nature of rights

Children’s rights are interconnected and indivisible. This may sound complicated but it means that they are all linked together and all equally important. Together they create a complete framework of rights that, if fully respected, would promote the health, welfare, development and active participation of all children.

To give two examples of this:

- It is not possible to tackle violence and sexual exploitation against children without also addressing the violation or neglect of rights that expose children to:

- violence

- poverty

- lack of access to education

- discrimination

- racism

- prejudice

- failure to listen directly to and take seriously what children say about their lives.

- Children’s right to optimum health and development cannot be fulfilled without a commitment to address their rights to:

- an adequate standard of living

- decent housing

- protection from economic exploitation

- protection from exposure to harmful work

- information to help them make informed choices

- information to help them protect themselves.

The fulfilment of all rights is essential for children’s optimum health and development. There is often a tendency to view physical needs as having priority. Clearly, at one level it is true that without food children will die. However, it is also true that without education or play, children’s potential cannot be realised. And without respect and freedom from discrimination, their psychological and emotional well-being will be impaired. Children’s rights are mutually interdependent: none takes precedence over another.

1.6 Duties and responsibilities

One of the key aspects of a person having a right is that there is a corresponding responsibility on someone else to ensure that the right is fulfilled or respected. Children’s youth, vulnerability and lack of power mean that they are dependent on adults to ensure that their needs and rights are met. This places responsibility on adults to create the necessary conditions to ensure this happens.

The UN Convention describes governments as the primary duty bearers. This means governments, more than any other institution or organisation, have both the duty and the responsibility of fulfilling the rights of children. These responsibilities include the fulfilment of rights for individual children; for example, access to health care and education. They also include the development of public policies that positively influence children’s health and development; for example, adequate housing, safe transport, protection of the environment, a healthy economy and the elimination of poverty.

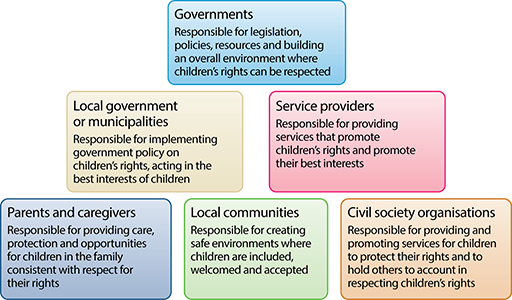

Many other groups also have responsibilities, including local authorities, health service providers, communities, parents and other caregivers. The UN Convention provides some guidance on the different responsibilities of governments and families in ensuring children’s rights are realised. For example, it emphasises that governments must respect the role of parents or caregivers as having primary responsibility for the guidance, upbringing and development of the child.

However, the UN Convention also stresses that the best interests of the child will be the basic concern. In other words, parents and caregivers must always take into account the child’s best interests in all decisions and actions that affect the child. And this means ensuring that their rights are respected. This includes, for example, ensuring that both boys and girls are provided with equal shares of food within the family, or not disciplining children using physical violence. A parent’s role is to promote the full, healthy development of their children, taking into account their age, abilities and evolving capacities. Parents should ensure that the child’s physical, psychological, social and spiritual needs and rights are met.

A brief overview of responsibilities of key duty bearers are outlined in Figure 1.1 below.

An old African proverb (Kiswahili) – It takes a village to raise a child

In relation to health, for example:

- The government has a responsibility to ensure that sufficient resources are allocated for health care services, training of doctors and nurses, and ensuring that services are available for all children, wherever they live in the country.

- A hospital or clinic has a responsibility to provide a professional, efficient and inclusive health service for all children who need information, advice and treatment regarding their health.

- Health workers have a responsibility to treat all children with respect, without discrimination, and to ensure that the children are as fully involved in their own health care as possible.

- The family or caregiver has a responsibility to provide, as far as possible, a healthy environment for the child to grow up in, with sufficient food, care and shelter, and to ensure s/he gets access to health care whenever needed.

Children also have responsibilities:

- To themselves – to do whatever they can to ensure their own safety, health and learning.

- To other children – to be caring, responsive and protective of other children and not act in ways that prevent their rights being realised; for example, bullying, or disruptive behaviour in school.

- To their families – to contribute to the life of the family, support their parents and show appropriate respect for elders.

- To their community – to contribute positively and as far as possible towards community life and their own environment.

However, it is important to remember that rights are ‘inalienable’ – this means that they cannot be taken away. Rights are not dependent on children exercising responsibility. For example, children cannot be denied the right to health care because they have acted in ways that place their health at risk.

1.7 The Committee on the Rights of the Child

The Committee is an international body of 18 independent child rights experts. They are elected by the governments that have ratified the UN Convention. Each member of the Committee serves for four years, and can be re-elected at the end of that time. Their task is to monitor governments to see if they are taking the necessary actions to ensure the rights of children.

Governments who have ratified the UN Convention are required to produce a report for the Committee every five years. The Committee reviews these reports, and encourages national non-governmental organisations (NGOs), coalitions and other expert bodies to submit reports highlighting the gaps and challenges to respecting and realising children’s rights in each country. The Committee meets with a delegation from the government and, after analysis and discussion, it produces recommendations to the government. The government is then expected to act on these recommendations.

Activity 1.4: Children’s rights in your country

Having looked in more detail at the Articles of the UN Convention:

- Which two areas of children’s rights do you think your country is doing well on?

- Which two areas of children’s rights do you think your country needs to do more work on?

Discussion

The answer to these questions will obviously depend on where you live and work, but from your experience in your community and as a health worker, you will probably be aware of ways in which children’s well-being is promoted. For example, in recent years, many governments have invested in expanding primary education to try to ensure universal access to education. However, you may be aware of problems that children are experiencing that the government does not seem to do anything about; for example, being beaten by teachers when they go to school.

If you have access to the internet, you can find the latest report to the UN Convention for your country and the Committee’s response. To do this:

- Go to the United Nations website at: http://tbinternet.ohchr.org/ _layouts/ treatybodyexternal/ TBSearch.aspx?Lang=en

- Under the heading ‘Filter by State’, tick the box next to your country.

- Under the heading ‘Filter by Committee’, tick the box next to where it says ‘CRC’.

- Under the heading ‘Filter by document type’, tick the box next to where it says ‘reports’.

- You will see that the reports from the governments are called State Party’s Reports.

You may need to scroll up and down to find the right boxes to tick.

1.8 African Charter on the Rights and Welfare of the Child

The African Charter on the Rights and Welfare of the Child (ACRWC) was adopted in July 1990 by the Organisation of African Unity (OAU), now the African Union (AU). The Charter came into force on 29 November 1999. Its main purpose was to adapt the rights contained in the UN Convention in order to address the particular challenges facing the African child, and also to encourage the Convention’s implementation. The content of the Charter is similar to that of the UN Convention: many of the rights are the same but it does differ in a number of ways.

The key differences between the African Charter and the UN Convention are that the Charter:

- prohibits child marriages

- insists on 18 as a minimum age of marriage

- requires that all marriages are registered in an official registry

- requires that pregnant girls have the right to continue their education

- includes a reference to protection from Apartheid

- insists that no child under 18 years can be recruited into the armed forces or take part in hostilities

- has no references to the right of a child to an adequate standard of living

- includes an Article setting out the responsibilities of children (this is not included in the UN Convention)

- includes an Article on the rights of children of imprisoned mothers (again absent from the UN Convention)

- makes more explicit reference to the family as the natural unit and basis of society.

Like the UN Convention, the African Charter also provides for an independent committee to monitor governments’ progress in implementation. It is called the African Committee on the Rights and Welfare of the Child. It has 11 members who are elected for five years, and governments must submit reports to them every three years.

Look at the two pictures below. According to the African Charter:

- Should a child be involved in armed conflict?

- Does a young mother have the right to continue with her education?

1.9 Guiding principles of the UN Convention and the African Charter

The Convention and the Charter contain four rights that have also been adopted as guiding principles. They are:

- The right to non-discrimination (Article 2)

- The best interests of the child must be a primary consideration (Article 3)

- The right to life and optimum development (Article 6)

- The right to be heard and taken seriously (Article 12)

In other words, these four rights must guide the way all other rights are implemented. This means that, for example, when looking at the right to health, the guiding principles must inform the way you treat a child, and the way services are run.

Note

For ease of reading, in the following text we refer only to the UN Convention when explaining the general principles: however, our discussion applies equally to the African Charter.

The right to non-discrimination

All rights in the UN Convention apply to all children without discrimination on any grounds.

Discrimination can be defined as:

any distinction, exclusion, restriction or preference which is based on any ground such as race, colour, sex, language, religion, political or other opinion, national or social origin, property, disability, birth or other status, and which has the purpose or effect of nullifying or impairing the recognition, enjoyment or exercise by all persons, on an equal footing, of all rights and freedoms

In order to fully realise the right to health for all children, governments must ensure that children’s health is not undermined as a result of discrimination, such as:

- Gender-based discrimination including female infanticide, discriminatory infant and young child feeding practices, gender stereotyping and unequal access to services. Attention should be given to differing needs of girls and boys, and the way in which cultural attitudes and practices affect their health and development.

- Harmful gender-based practices, such as female genital mutilation or scarring that undermine the right to health of girls and boys, should be given more attention by health practitioners.

- Children in disadvantaged areas, like refugee camps and rural areas, may receive a poorer service.

All these factors should be considered by governments when developing programmes and policies that work towards ensuring equity.

The best interests of the child

This Article and guiding principle requires that all public and private organisations have to make sure that the best interests of the child is a primary concern when they are taking action that might affect them. This requirement obviously applies to health workers and health services. For example, a decision to treat a child must always be made in his or her best interest and not just to contribute to research findings or to provide a doctor with more experience.

Decisions about the management of children’s hospital wards must be made in the best interests of the child, not for the convenience or efficiency of the staff. This does not mean that the best interests of children is the only consideration: other people’s interests must also be taken into account. However, health authorities and professionals must always consider the potential impact of their actions on children and seek to ensure that children’s interests are given serious attention.

In order to try to decide what is in a child’s best interests in any given situation, it is helpful to think about what rights are involved and how best to protect them. For example, before giving an injection to a child who is capable of understanding, it will be in her or his best interests to provide them with information about what is going to happen, and why the injection is needed. You can also ask them if there is anything you can do to make them feel less anxious and tense. In other words, respecting a child’s right to information and to be heard will be in their best interests.

The right to life and optimum development

This Article stresses the right of every child to life, survival and development. It means that governments must ensure that health services are designed to protect the lives of children. But it goes further than this. Governments must also try to create an environment in which children’s development can flourish. It means that the lives of all children must be equally protected, irrespective of disability, gender, ethnicity or any other factors.

This does not always happen. For example, in a recent consultation with young people in Tanzania for this course, they described examples of albino children who were thought to be affected by a curse and injected with overdoses of drugs so that they would die.

Look at the picture below. What does this child require for optimum survival?

The right to be heard and taken seriously

Children have the right to be able to express their views on all matters affecting them and to have those views taken seriously, in accordance with the child’s age and maturity. This does not mean that you must do whatever children want. However it does mean that their feelings, concerns and ideas should be taken into account when you are making decisions about them. This involves both listening and taking on board what the children say.

Activity 1.5: Providing health services to adolescent children

Read the following case study.

Case study

A local health centre, in partnership with an NGO that was providing health services to adolescents in the local schools, was doing research into sexually transmitted infections [STIs]. A group of health practitioners visited a secondary school in the local area to conduct the research on the prevalence of STIs.

The practitioners sought permission from the institution’s administration to provide children for them for test. The children were picked randomly and asked to provide specimens of urine, blood and stools for analysis. The results indicated that two of the girls’ specimens revealed an STI infection and one girl tested HIV positive. The results were left with the school administration, and prescription medicine was left with the school principal to administer to the children.

The principal then announced the results in the school assembly and lectured the students not to be involved in sexual activities because some of them had been diagnosed as HIV positive. The affected children were then given the medicine that had been left for them.

The children completely refused to take the medicine and reported the matter to their parents, who were enraged over the whole incident. The girl who was supposedly diagnosed as HIV positive ran way from school and drowned in the nearby river.

Now answer the questions below.

- What rights do you think were violated by the various people in the case study? The health workers? The headmaster?

- What should have happened if the four guiding principles were to be respected?

Discussion

The case study illustrates a number of ways in which the rights of the children were ignored.

For example you will have noticed that the practitioners only asked permission from the school to administer the tests and did not discuss the matter with the children or their parents. This obviously violates the right to be given information (Article 13) and for ‘the child who is capable of forming his or her own views the right to express those views freely in all matters affecting the child, the views of the child being given due weight in accordance with the age and maturity of the child’ (Article 12).

The results were not discussed with the children or with their parents, and there was no confidentiality for the children affected by this very sensitive medical issue. As a result of the way in which the situation was handled, the two girls affected felt discriminated against, and ultimately one of them died. Certainly, her right to life and optimum development was not protected.

The decisions here were not taken with the best interests of the children being a primary or even the most important consideration. The parents were not involved, and it is important to note that, because of the way the situation was handled, the attempt at a preventative medical intervention was also unsuccessful as the children did not take the medication.

You will probably have identified that good practice here is almost the opposite of what happened. The children should have been given the correct information and asked their views, and their parents should have been involved by the school. The girls should not have been made to feel discriminated against.

The Committee on the Rights of the Child stresses that proper treatment of HIV/AIDS can be undertaken only if the rights of children and adolescents are fully respected. The child’s best interests should therefore guide the consideration of HIV/AIDS at all levels of prevention, treatment, care and support.

1.10 Summary

- The UN Convention and the African Charter contain rights relating to the provision of services, such as education and health; protection from harm, such as violence and exploitation; and participation, including the right to be heard and to be given information.

- Four general principles of the UN Convention and the African Charter need to inform the realisation of all other rights: non-discrimination, maximum survival and development, the best interests of the child and child participation.

- The UN Convention and the African Charter both address the wide-ranging rights of children, but the African Charter has adapted some of those rights to address the particular situation of children in Africa.

- All rights are interconnected and indivisible.

- There is an international body called the Committee on the Rights of the Child, which is responsible for monitoring how far governments are progressing in implementing the UN Convention. A similar body exists for the African Charter.

- The rights contained in both the UN Convention and the African Charter have direct relevance for the role of health workers, and need to be understood and addressed in your day-to-day work.

1.11 Self-assessment questions

Question 1.1

Describe the three broad categories of rights in the UN Convention and the African Charter.

Question 1.2

Explain how each of the UN Convention and the African Charter categories are relevant to your role as a health worker.

Question 1.3

Explain the guiding principles of the UN Convention and the African Charter and why they are important.

Question 1.4

Provide an example of what changes you could make in your practice to ensure that:

- a.Children with disabilities are not discriminated against.

- b.Girls are treated equally with boys.

1.12 Answers to activities

Activity 1.2: The 3 Ps

You could have included the following as your examples of a child’s rights for each of the 3 Ps:

| Category | Right | Article |

|---|---|---|

| Provision | For example: Health care | 24 |

| Play | 31 | |

| Education | 28 | |

| Protection | For example: Protection from abuse and neglect | 19 |

| Protection from economic exploitation | 32 | |

| Protection from sexual exploitation | 34 | |

| Participation | For example: Right to information | 13 |

| Right to express views and have them taken seriously | 12 | |

| Right to freedom of religion | 14 |

2 National laws and policies

Focus question

How are children’s rights and protections supported by laws and policies in East Africa?

Key words: Act, Constitution, Law, Policy

2.1 Introduction

In the last study session you learned about the international and regional laws that govern children’s rights. In this session we will look at some of the measures that have been introduced in Ethiopia, Kenya, Tanzania and Uganda to implement children’s rights into national laws. All four countries have introduced laws that incorporate the key rights and principles outlined in the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child and the African Charter on the Rights and Welfare of the Child. They set out the rights of children, the responsibilities of governments to protect those rights and the penalties associated with failing to respect them.

The study session will focus on those areas of the legislation that are of particular relevance to health workers. It is important to understand what rights children have and how the law protects those rights. This knowledge will help you to understand how to respect children’s rights in your day-to-day work, and how to take action if you see that children’s rights are not being respected by others.

2.2 Learning outcomes

When you have studied this session, you will be able to:

- define and use correctly all the key words used in this study session

- explain why it is important to introduce national laws and policies to protect children’s rights

- understand how the laws and policies in your country provide for children’s rights to care, to protection from violence and abuse, to information and to be heard

- demonstrate your understanding of the relevance of these laws and policies for your practice as a health worker.

2.3 Understanding the laws and policies that protect children’s rights in East Africa

Activity 2.1: Role of national laws and policies

Can you think of any reasons why it is important to have national laws and policies when we already have the UN Convention and the African Charter?

Discussion

Although Ethiopia, Kenya, Tanzania and Uganda have all ratified both the UN Convention and the African Charter, this does not, on its own, provide sufficient protection to ensure children’s rights. Those rights also need to be introduced into national constitutions or laws and policies. This shows that each country is taking the issue of children’s rights seriously and is applying it specifically to their own situation.

Legislation

A law can lay out in much more detail how the provisions of the UN Convention and the African Charter are expected to be applied in practice in a particular country. National laws can also provide a means through which children and their families can hold governments, and other duty bearers, to account on the commitments they have made on children’s rights. For example, the UN Convention states that every child has a right to free primary education. However, only if a government introduces this provision into national legislation is it possible for individuals to challenge the government, and seek justice in court if necessary, if no free school place is available.

Laws are introduced through Acts of Parliament. The four countries of Ethiopia, Kenya, Tanzania and Uganda have each introduced Acts of Parliament that establish a broad range of children’s rights. The Acts also set out who is responsible for protecting children’s rights, and introduce the bodies with responsibility for overseeing that protection; for example, National Councils for Children’s Services, or juvenile courts.

Constitution

All four countries have a constitution, and in Ethiopia, Kenya and Uganda the constitution makes specific reference to children’s rights. A constitution is a set of fundamental principles, a framework of laws and established principles according to which a state is governed. In most countries any amendment to a constitution is designed to be a difficult process in order to give the constitution greater stability.

All laws and policies must comply with the constitution. For example, the Kenyan Constitution 2010 states that every child has the right:

to be protected from abuse, neglect, harmful cultural practices, all forms of violence, inhuman treatment and punishment, and hazardous or exploitative labour.

This means that it is not possible to introduce a law that undermines or reduces that right.

Policy

Once a law is enacted, it is usually necessary to introduce a policy that describes in more detail exactly how the provisions of the law must be applied. For example, while a law can establish the right of every child to health care, a policy will be needed to provide guidance on issues such as:

- the overall goals for the health of citizens

- the priority areas

- the budgetary allocation

- the organisation and structure of the health system

- how health care will be delivered

- the level of service to which individuals are entitled

- who is responsible for what aspects of health care.

Figure 2.1 shows how each of these layers is needed to provide a secure basis for children’s rights. The final step is that practitioners in health care (as well as those in education, the courts, the police force and all other services) ensure both the law and the policy are implemented for the benefit of children.

Further information

Acts that incorporate children’s rights into domestic law:

- The Children Act, 2001 (Kenya)

- Law of the Child Act, 2009 (Tanzania)

- The Children Act, Chapter 59, 1997 (Uganda)

- Constitution of the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia (FDRE) and the Revised Family Code, Proclamation No. 213/2000 (Ethiopia)

Although these national laws on children cover many different areas of rights, we will focus in this study session on four of the key provisions that are of particular relevance to health workers – a child’s right to be:

- cared for and looked after

- protected from violence and abuse

- given information

- heard and involved in health care decisions.

2.4 The law and the child’s right to be cared for and looked after

Children, because of their vulnerability and lack of power, require special care and protection to enable them to develop to their full potential. The UN Convention therefore introduced a number of responsibilities obliging parents and governments to provide that care and protection. For example:

- The obligation to give the child’s best interests primary consideration (Articles 3 and 18)

- The responsibility of parents or guardians for the upbringing and development of children (Article 18)

- The responsibility of governments to provide assistance and support to parents to help them care for their children (Article 18)

- The right of children to special protection and assistance if their parents cannot care for them (Article 20)

- The right of children to an adequate standard of living, and the responsibility of governments to provide help where necessary with nutrition, clothing and housing (Article 27).

Many of these rights and responsibilities have been incorporated into national legislation in Ethiopia, Kenya, Tanzania and Uganda. The overall aim of these rights and responsibilities is to ensure that children achieve their best possible development, and are able to live constructive lives and participate actively within their communities.

Key provisions

The following table provides an overview of some of the key provisions that protect children’s rights in national law.

| Ethiopia: Revised Family Code; Ethiopian Criminal Code; FDRE Constitution | Kenya: The Children Act, 2001 | Tanzania: Law of the Child Act, 2009 | Uganda: The Children Act, Chapter 59 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Definition of a child | All persons below the age of 18 are minors and the minimum age of marriage is 18. | A child is defined as any person under the age of 18 years. | A person below the age of 18 years shall be known as a child. | A child is a person below the age of 18 years. |

| The best interests principle | The best interests of the child shall be the primary consideration in all actions concerning children by public institutions, courts of law, administrative authorities or legislative bodies. | In all actions concerning children, whether undertaken by public or by private social welfare institutions, courts of law, administrative authorities or legislative bodies, the best interests of the child shall be a primary consideration. | The best interests of a child shall be the primary consideration in all actions concerning a child, whether undertaken by public or by private social welfare institutions, courts or administrative bodies. | Whenever the State, a court, a local authority or any person determines any question with respect to the upbringing of a child, the administration of a child’s property, or the application of any income arising from it, the child’s welfare shall be the paramount consideration. |

Parental responsibility | Both parents have the responsibility for the proper upbringing of their children. | Parental responsibilities include:

| Every parent shall have duties and responsibilities, whether imposed by law or otherwise, towards his child, which include the duty to:

| Every parent shall have parental responsibility for his or her child. Where the natural parents of a child are deceased, parental responsibility may be passed on to relatives of either parent or, by way of a care order, to the warden of an approved home, or to a foster parent. |

| Support for vulnerable children and families | The law … gives priority to the well-being, upbringing and protection of children in accordance with the Constitution and International Instruments that Ethiopia has ratified. | The National Council for Children’s Services is responsible for the formulation of policies on family employment and social security that are designed to alleviate the hardships that impair the social welfare of children. It also works towards the provision of social services essential to the welfare of families in general and children in particular. | The local government authority shall have the duty to keep a register of most vulnerable children within its area of jurisdiction and to give assistance to them whenever possible in order to enable those children to grow up with dignity among other children and to develop their potential and self-reliance. | It shall be the general duty of every local authority:

|

| Alternative care for children | Special protection is afforded to orphans, and the State encourages the establishment of institutions that ensure and promote their adoption, and advance their welfare and education. | The National Council for Children’s Services has responsibility for ensuring the welfare of children unable to be cared for by their parents. A care order can be made when a child is in need of care and protection. | A court may issue a care order or an interim care order on application by a social welfare officer for the benefit of a child. The care order or an interim care order shall remove the child from any situation where he is suffering or likely to suffer significant harm and transfer the parental rights to the social welfare officer. | A care order can be made to remove a child from a situation where he or she is suffering or likely to suffer significant harm; and to assist the child and those with whom he or she was living or wishes to live to examine the circumstances that have led to the making of the order and to take steps to resolve or ameliorate the problem so as to ensure the child’s return to the community. |

| Health and well-being | The guardian is responsible for the health of a child. The law provides for free access to health services for those who cannot afford it. | Every child shall have an inherent right to health, and it shall be the responsibility of the government and the family to ensure the survival and development of the child. | The parent or guardian is responsible for ensuring the right of the child to immunisation and medical attention. | It is the duty of the parent or guardian to ensure the right of the child to medical care, including immunisation. |

You will see from the table that in all four countries the laws describe situations not in terms of children’s needs, but in terms of the obligations to respond to the fact that children have rights. The laws also make clear that both parents and governments have responsibilities for ensuring the care and well-being of children.

Role of family and State

The family is recognised as playing a unique and vital role in the lives of children. These national laws all reflect the UN Convention views that the family is the fundamental group of society and the natural environment for the growth and well-being of its members.

However, the family can only fulfil their role if the government creates the necessary environment for the protection of children’s rights. For example, while parents have the primary responsibility for ensuring the health of their children, they can only do this if the government fulfils its responsibilities to provide access to health care, clean water, sanitation and housing. Such assistance may include, for example, free health care for children under five years of age, or cash transfers to vulnerable families including those with disabilities.

The aim is to strengthen families’ capacities to take care of their children. Parents, for their part, must then respect their child’s right to health by complying with the law.

Activity 2.2: Balancing the rights of the child with the rights of the parents

Read the following case study.

Case study

Baby John was only six months old when he developed a very high fever. However, the parents, being strict followers of a church that emphasised faith healing, would not take him to hospital. They said that their faith in God would heal the baby and, even if he died, that would be the will of God. The authorities forcibly removed the baby and took him to the hospital because the parents insisted that they would not give the baby any medicine even if they were jailed. The parents were later prosecuted in a court of law for denying the child his right to health.

Now answer the questions below.

- Look again at your UN Convention resource. What rights does baby John have that are relevant in this story?

- What does this case study tell you about the responsibilities of the parents and the State for the rights of the child?

- Do you think the balance between the rights of the parents and the rights of the baby were dealt with appropriately? Explain why you answered the way you did. If you are working in a group discuss this question.

Discussion

- Rights that are of relevance to this case study are:

- The right to life

- The right to optimum development

- The right to the best interests of the child being a primary consideration

- The right to the best possible health

- The right not to be harmed by traditional practices prejudicial to a child’s health.

- Although parents do have primary rights and responsibilities in relation to the care of their children, these rights are not absolute. They apply only for as long as the parents are acting in the best interests of their child and not placing them in situations where their health and well-being are at risk. If the parents’ actions are leading to neglect or serious harm to the child, then the government has a duty to intervene to protect the child and override the rights of the parents.

- This story involves a balance between the rights of the parents and the rights of their child. Clearly, parents have the right to determine when their child needs medical treatment and to give or to refuse consent to that treatment on behalf of a child, at least until the child is competent to exercise that right for herself or himself.

However, if the exercise of parental rights is likely to lead to the death or the serious ill-health of that child, then the right of the child to life and to the best possible health must override the parental rights. Again, the best interests principle must apply.

It seems clear that in this story the local authorities were correct in using the law to prioritise the rights of the child. Failure to have done so could have led to the child’s death. Although the parents are entitled to their own beliefs, they do not have the right to impose those beliefs on the child if doing so will result in harm.

2.5 The law and the child’s right to protection from violence and abuse

Article 19 of the UN Convention and Article 16 of the African Charter define violence as including all forms of:

- physical or mental violence

- injury or abuse

- neglect or negligent treatment

- maltreatment or exploitation, including sexual abuse.

Despite this right to protection in these articles, there is significant evidence of violence against children across East Africa. Widespread social and cultural attitudes and practices condone violence as a way of disciplining children. Violence and abuse is committed primarily by those closest to the children – parents, family members, neighbours and peers.

In addition, the UN Study on Violence against Children (2006) revealed that children in Africa run a high risk of violence in many different settings, including child-centred organisations. Children receiving social, educational, health and other services are not adequately protected from abuse and exploitation by staff and associates, as well as by the community at large.

It is important to note that the Committee on the Rights of the Child has stressed that no violence against children is acceptable, including corporal punishment.

In response to their international obligations under both the UN Charter and the African Charter, all four countries have adopted provisions that incorporate into national laws the right of children to protection from violence, although the scope of the provisions varies.

Ethiopia

The Constitution recognises the right of every person, including children, to protection against bodily harm and to protection against cruel, inhuman and degrading treatment and punishment. It also specifically recognises the rights of every child to be free of corporal punishment or cruel and inhuman treatment in schools and other institutions responsible for the care of children. Legislation also prohibits forms of harmful traditional practice, such as uvula and tonsil scraping and female genital mutilation.

Kenya

The Children Act states that:

- A child shall be entitled to protection from physical and psychological abuse, neglect and any other form of exploitation including sale, trafficking or abduction by any person.

- Any child who becomes the victim of abuse shall be accorded appropriate treatment and rehabilitation in accordance with such regulations as the Minister may make.

- No person shall subject a child to female circumcision, early marriage or other cultural rites, customs or traditional practices that are likely to negatively affect the child’s life, health, social welfare, dignity or physical or psychological development.

The Constitution further provides that everyone, including children, has the right not to be subjected to corporal punishment. This provision applies to corporal punishment in the home, in schools, in institutions and as a sentence for a crime.

Tanzania

The Law of the Child states that a person shall not subject a child to torture, or other cruel, inhuman punishment or degrading treatment, including any cultural practice that dehumanises or is injurious to the physical and mental well-being of a child. No correction of a child can be justified if it is unreasonable in kind or in degree, according to the age, physical and mental condition of the child, and no correction can be justified if the child is incapable of understanding the purpose of the correction. However, no explicit provisions yet exist to prohibit corporal punishment in the home, in school or in other institutions for the care of children.

Uganda

The Children Act states that any person having custody of a child shall protect the child from discrimination, violence, abuse and neglect. It also bans subjecting a child to social or customary practices that are harmful to their health. A ministerial circular (2006) and the Guidelines for Universal Primary Education (1998) state that corporal punishment should not be used in schools, but there are no provisions in law prohibiting corporal punishment in all settings.

You will see from this brief overview of the laws that while all the countries in East Africa have introduced some protections for children, not all of them explicitly prohibit all forms of violence against children.

Activity 2.3: Common abuses of children’s rights

Look at the list below. Which of these practices do you think are common in your country? Choose a number between 1 and 5 that represents how common you think the practice is, where 1 is common and 5 is rare. If you are working in a group discuss your experiences that led to your decision.

Bearing in mind the practices you think are common in your country, why do you think children’s rights to protection from violence and abuse continue to be violated?

| Common | Rare | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Corporal punishment in schools using a stick | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Children denied food in school as a punishment | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Punishment at home using a stick | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Girls/young women undergoing genital mutilation | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Sexual abuse of a child by a family member | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

Discussion

From the information you have been given, you can see that the laws in Ethiopia, Kenya, Tanzania and Uganda all prohibit physical abuse, corporal punishment in school and harmful traditional practices. Yet you may be aware of these practices continuing. While the extent of these practices will vary between communities there is clear evidence that all of these issues are widespread.

Why do these practices continue? There is often insufficient attention given to the implementation and enforcement of legislation. Too often, individuals and communities are unaware of the law. Even if they are aware of the law, they may not know how to seek protection or redress against violations of their rights.

In some communities there is deep resistance to change. It is important for governments to work with communities to raise awareness and to help communities understand why these rights are important. Communities and parents need to understand not only why children need greater protection but how to, for example, introduce alternative practices and rites of passage that are not harmful to the child.

This is not only the responsibility of government; health practitioners too can play a role in raising awareness of the law and challenging practices, as the next section will make clear.

A 12-year-old pupil at a Kampala school and his family are battling school authorities after he lost a tooth to a teacher who subjected him to corporal punishment.

School head teacher, XXX, declined to give details when Education contacted her, saying only: ‘that case was closed. If you want to know details you can contact Makerere Police’.

The incident is one of continuing use of corporal punishment in schools despite the fact that it was outlawed several years ago. According to the African Network for the Prevention and Protection against Child Abuse and Neglect (ANPPCAN), physical violence accounts for 81 per cent of children who have been beaten at school despite the Ministry of Education’s policy against corporal punishment.

‘I think that corporal punishment has become socially acceptable. The society thinks it is normal but this is wrong and must stop,’ said Anselm Wandega, ANPPCAN executive director.

Some other 34 per cent of children are denied food for extended periods at a time, 82 per cent are made to do difficult work as a form of punishment, while 18 per cent have been locked up in a room, ANPPCAN statistics show.

Why health workers need to know the law

Research shows that children who have not experienced violence are less likely to act violently, both in childhood and when they become adults. More than 150 studies on the impact of corporal punishment, for example, show that it is associated with a wide range of negative outcomes, while no studies have found evidence of any benefits (Global Initiative to End All Corporal Punishment of Children, 2013).

Effective prohibition contributes to the prevention of domestic violence, mental illness and antisocial behaviour, and supports the well-being, education and positive developmental outcomes for children. Therefore preventing violence in one generation reduces its likelihood in the next.

However, a major challenge facing health workers in the region is the poor enforcement of the laws and policies, and the extent of mistreatment of the child within the family.

The introduction of legislation to provide protection is only the first step. There is also a need for policies to promote the implementation of the law, as well as mechanisms through which the law can be enforced. It is important to bear in mind the issues raised earlier concerning parental and children’s rights. The law does, for example, restrict parental rights to use harsh physical punishment to discipline their children. As a health worker, you will be a witness to the harm caused to children as a result of such punishment. You need to be clear about the right of children to protection from such harm, and your legal and ethical responsibility to protect them from further harm.

You also need to be familiar with the policy – the local mechanisms for reporting, referring, investigating and eventually treating. At the same time as addressing the right to protection from harm, you must also have a regard for the child’s right to express their views and to do so in private. The right to be heard and taken seriously can contribute significantly to the prevention of all forms of abuse in the home and the family.

Activity 2.4: Policies to protect children from violence

Consider the following questions. Discuss them with colleagues to explore how the issues are thought about in your community.

- What evidence of violence against children do you see in your health setting?

- Do you know what systems or structures are in place to provide protection for children within your community, and how effective they are?

- What strategies could be developed in health settings and in the community to help reinforce these laws and policies?

Discussion

- Do you see children coming to clinics who have been seriously beaten or harmed by their parents, or by other people they know? Do you routinely report these cases?

How does the local community react to these cases? Are they taken seriously as a matter of concern?

Discussing these issues will help you begin to build up a picture of both the prevalence and nature of violence against children, and whether law and policy are being followed.

- It is essential that you know where a child can report a case of violence or abuse. Would they go to the local magistrate? Or to the police? Is there a community-based child protection committee and, if so, who are the members? Do children know where to go for help and do they use those systems?

You can share your knowledge of the law with others. Is the health worker mandated by the law to examine the victim and then present his/her findings to a court of law for purposes of prosecution of the offender? In Uganda, for instance, Article 17 of the Children Act states that it is the duty of every citizen, including health workers, to protect children against any form of abuse, harassment or ill treatment.

- There are a number of measures that you might have thought of that could be implemented locally, for example:

- Training practitioners on child rights, the law and the role of professionals in protecting children

- Drawing up clear guidelines for health professionals on how and where to report instances of abuse

- Establishing local mechanisms to protect women and children against harmful traditional practices

- Developing and supporting community-based child protection systems

- Awareness raising to ensure that children know their rights and how to exercise them

- Effective and transparent complaints, monitoring, investigation and redress mechanisms.

A serious commitment to ending violence against children requires comprehensive policies at all levels of society to ensure that any laws that have been introduced are actually implemented on the ground.

Activity 2.5: Reporting mechanisms

What is the reporting mechanism in your workplace, for you as a health practitioner, if you suspect a child is being abused by someone in their own family? Who do you tell and when?

If you do not know – find out – and record the procedure.

Comprehensive Community Based Rehabilitation Hospital in Tanzania [CCBRT] has developed a child protection policy to ensure that when children seek health services there, they are treated with dignity and respect. It is a best practice that needs to be scaled up in Tanzania and replicated in other countries. CCBRT is guided by the UN Convention as the benchmark for upholding child rights. Integral to the CCBRT is the child protection policy that all staff members, consultants, visiting doctors, journalists and other people are required to sign up to. The code of conduct lays down clearly defined standards, rights and responsibilities for all CCBRT stakeholders in respect of child protection (CCBRT, n.d.)

2.6 The law and the child’s right to information

What sort of information do you think children in your local community might need?

Article 17 of the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child provides that children have a right to information. At national level, a child’s right to information is not explicitly stated in the laws in any of countries in the region. However, all four countries have very clear legislation affirming a child’s right to basic education, which is a key means by which children acquire information.

As a health worker, there are three key aspects you should understand in relation to a child’s right to information:

- Information about rights: Children cannot exercise their rights unless they know that they have rights, what those rights constitute and where to get assistance in case of any violation of their rights.

In relation to health, for example, children need to know about what the right to health means, their right to protection from violence, their right to be involved in decisions that affect them, and if and when they are entitled to give consent to their own health care and treatment.

The Committee on the Rights of the Child emphasises the importance of human and child rights education in the school curriculum (CRC, 2001). In Kenya, for example, the government has incorporated child rights education as a primary topic to be covered within social studies in the primary level education curriculum.

- Access to health education and information: Education and access to health-promoting information can play an important role in protecting children and enhancing their capacities to make informed decisions in relation to their own health care.

As a health worker, you can play a key role in ensuring that children have the necessary health knowledge and skills to make positive choices and live healthy lives, as well as helping children understand their rights in relation to health care and protection. This might include, for example, information about:

- how they can lead healthy lives

- sexual and reproductive health

- HIV/AIDS awareness

- nutrition

- smoking

- alcohol

- illegal drugs

- physical and psychological development.

Health workers can also develop preventive and promotional materials in forms that the child understands and that are appropriate to the child’s evolving capacities. This can be done in partnership with children themselves. Children can also be provided with advice on where they can go for further information and help.

- Protection from harmful media and information: Children have the right to protection from harmful information. Some laws exist to provide guidance on the type of information that children can access or be exposed to. For example, in Kenya, exposure to obscene materials or pornography is prohibited. However, many children do have access to harmful or pornographic materials; for example, through internet cafes. This exposure may have an impact on levels of sexual violence, and vulnerability to abuse.

2.7 The law and the child’s right to be heard and to be involved in health care decisions

As you learned in the previous study session, Article 12 of the UN Convention states that every child capable of forming a view has the right to express that view and have it taken seriously in accordance with age and maturity. This provision is generally known as participation of the child. It has been incorporated into the national laws in East Africa as follows:

Ethiopia: Article 29 of the Constitution enshrines the right of every citizen to freedom of expression and access to information. The Revised Family Code also recognises the principle of child participation in some processes. For example, in adoption, the Court must consult the child and seriously consider his or her opinions (Article 194/3/a). There is also a discretionary power for the court to consult the child before deciding on the appointment or removal of guardians and tutors of the child. Finally, where there are disputes between parents on the matter of child custody, the court is expected to make a decision after hearing the opinion of the child.

Kenya: The Children Act requires that in any decision made by the Children’s Court, it must have regard to the ascertainable wishes and feelings of the child, with reference to the child’s age and understanding. The Court can also order that the child has legal representation. The wishes and feelings of the child must also be taken into account when determining custody of the child. An adoption order requires the consent of the child if she or he is 14 years or over.

Tanzania: The Law of the Child Act states that a child has the right to an opinion, and that no one can deprive a child capable of forming a view of the right to express an opinion and to participate in decisions that affect him or her. In addition, the Act requires that social welfare officers involved in care and protection cases must consult with the child when planning for the child’s future. When courts make care or supervision orders, children must be interviewed by social welfare officers if the children are of sufficient age and maturity and their views reported to the court. In parental custody disputes the views of the child must be taken into account. In adoption cases the wishes of any child capable of forming an opinion must be taken into account, and the consent of a child aged 14 and over must be given before an order can be made.

Uganda: A guiding principle of the Children Act is that in making any decision concerning a child, the courts or any other person shall have regard in particular to the ascertainable wishes and feelings of the child concerned, and they must be considered in the light of his or her age and understanding. When making reports to the court in relation to supervision or care orders, social welfare officers are required to interview the child if he or she is of sufficient age and understanding. Social welfare officers are also required to bear in mind the wishes of the child in any follow-up work once the order is made. In adoption, the wishes of any child capable of forming an opinion must be taken into account, and the consent of a child aged 14 and over must be given before an order can be made.

Overall, you can see that many measures have been taken in all four countries to try to ensure the right of the child to be heard. Although there are no provisions that introduce specific rights in respect of being heard in health care decisions, in Tanzania and Uganda there is a general recognition in law that children have a right to be heard in all matters affecting them, and this extends to the field of health.

In Ethiopia and Kenya, where the provisions are related to specific proceedings, there is recognition of the fundamental importance of listening to children when key decisions concerning them are being made. So it is clearly in line with government policy in all four countries, as well as with the UN Convention, that efforts should be made to ensure that children are listened to in matters affecting their health care. This will apply, for example, in the following ways:

- Health workers generally tend to talk with the parents about the child’s condition, what treatment is needed and why, how it will be provided and when, and what will be the impact or consequences, while excluding the child from that conversation. The right to express views requires that children are directly involved in those discussions.

- Children sometimes need access to confidential medical counselling and advice, regardless of age, and without them having to get parental consent. It is important to recognise that the right to counselling and advice is distinct from the right to give medical consent and should not be subject to any age limit.

- Children will sometimes disclose information that indicates that they are seriously at risk of harm – for example they are being sexually abused – but they do not wish this information to be passed on to anyone else, or acted on. In these circumstances, it will be necessary for a health worker to consider how to balance the right to confidentiality with the right to protection. The health worker needs to appreciate that children should be invited to contribute their views and experiences to planning and programming of services for their health and development.

- Although health workers must comply with the laws in relation to consent to treatment, the philosophy of the UN Convention requires health workers to recognise the need to gradually involve children more fully in decisions relating to their health. Health workers also need to help parents recognise the importance of actively involving their children in decisions about their health care.

Listening to the voices of children

‘Parents can do what they like until you get married or become self reliant. Some parents force you to have an injection if they think you have started having sex rather than get the shame of a pregnancy.’

‘They broadcast your secrets. They start by telling their own family. I will go to another health facility far away.’

Activity 2.6: A child’s privacy versus parental rights

Read the scenario below and answer the questions.

A 16-year-old girl comes to your clinic. She wants to be given information and advice about contraception, but she does not want her parents to know.

- What questions might you ask the girl?

- Would you report the girl’s request to her parents?

- How would you respond to the request?

Compare your answer with the one given at the end of the study session.

2.8 Summary

This session was designed to help you understand how international human rights laws are translated into the national level to ensure the effective protection of children. In summary:

- In Ethiopia, Kenya, Tanzania and Uganda, the governments have introduced laws and policies to translate the UN Convention and the African Charter into national legislation.

- National laws and polices provide more detailed measures on how the rights of children must be respected.

- The child’s right to care and protection is a shared responsibility at many levels, including, for example, governments, parents and health workers.

- Although the family has the primary responsibility for the care of the child, the law allows governments to intervene to protect the child when it is in her or his best interests to do so.

- All four countries have national laws that provide protection to children from violence.

- All four countries have national laws that recognise the right of the child to express their views and have them taken seriously.

- Health workers have a key role to play in protecting children, providing them with appropriate information to make informed choices and ensuring that their voices are heard.

2.9 Self-assessment questions

Question 2.1

What does the law of your country say about protecting children from harmful cultural practices?

Question 2.2