Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Monday, 24 November 2025, 11:31 AM

Module 3: Module 3 - Children’s rights and health practice

Introduction to Module 3

This is the third module in a course of five modules designed to provide health workers with a comprehensive introduction to children’s rights. While the modules can be studied separately, they are designed to build on each other in order.

Module 1: Childhood and children’s rights

Module 2: Children’s rights and the law

Module 3: Children’s rights and health practice

Module 4: Children's rights in the wider environment: the role of the health worker

Module 5: Children’s rights: planning, monitoring and evaluation

Module 3 provides four crucially important study sessions for health care practitioners in relation to ensuring children’s rights in health care settings. Each of these sessions is designed to take approximately two hours to complete. The sessions provide you with an introduction to these topics and are supported by a range of different activities to help you develop your understanding and knowledge. The activities are usually followed by a discussion of the topic, but in some cases there will be answers at the end of the study session for you to compare your own answer to before continuing. We have provided you with space to write your notes after an activity, however if you wish, you can use a notebook.

- Study Session 1 stresses the importance of children being actively involved in their own health care. In the session you will explore the implications of listening to children and taking their views seriously. You will also learn about the importance of recognising children’s evolving capacities. By the end of the session you will have a better understanding of why the participation of children is so important and what are the main difficulties and challenges.

- Study Session 2 will introduce you to two important principles: the right of children not to be discriminated against and the need for adults to think about the best interests of children when they are making decisions on their behalf. It will help you explore the different forms of discrimination and the importance of treating children equally in a health care setting. The session will question how can we act to ensure the best interests of children and prevent discrimination? And how are the best interests of children to be determined and balanced against any other considerations?

- Study Session 3 is devoted to the topic of violence against children. It looks at how you can support the right of children to be free from violence and abuse. In this study session you will question your own views and attitudes towards violence, recognise the signs of abuse and understand the impact it has on children. By the end of the session you will have explored the important role of health practitioners in identifying and reporting violence against children.

- Study Session 4 focuses on an issue important to any health worker, which is how to make their practice environment ‘child-friendly’. You will consider what is meant by being child-friendly and the role that standards and charters can have in promoting a positive environment. By the end of the session you will have had the opportunity to reflect on your own health facility and plan how it can be improved to support the rights of children.

1 The child as an active participant

Focus question

Why should children be involved in making decisions concerning their health?

Key words: competence; confidentiality, decision-making, participation

1.1 Introduction

In this session you will learn about one of the fundamental rights contained in the United Nations (UN) Convention on the Rights of the Child. Article 12 of the UN Convention gives children the right to express their views and have them taken seriously. This means that children are entitled to be involved in decisions that affect them. It is commonly described as the right to participation. It challenges assumptions in East Africa that children are not expected to question or challenge adults or to contribute to decisions adults make on their behalf. Article 12 does not encourage children to be disrespectful or disobedient. It seeks to promote respect for children to be more actively involved in their own lives and to be able to influence the things that happen to them. Children are not just passive recipients of adult care and protection – they can also contribute to the exercise of their rights and participate in decisions that affect them.

This session will help you to explore your own views about child participation, to appreciate the capacity of children to influence decisions about their health. You will also think about why this is important for health workers to understand.

1.2 Learning outcomes

When you have studied this session, you will be able to:

- explain correctly the meaning of the above key words

- understand the right that children have to participate in their own health care

- discuss the benefits of involving children in decisions that concern their health

- identify situations in your practice where children should be involved in decision making.

1.3 Your own childhood experience

Activity 1:1 Thinking about your own childhood experience

Think back to when you were a child and try to remember a situation when you visited a doctor, a health facility or a hospital.

What was your experience like? Did the doctors or nurses you met ask you questions? Did they listen to your response? Did they explain what was happening to you? Did you have an opportunity to ask questions? Did they involve or encourage you in any other way?

How did your experience make you feel?

Discussion

It is a very common experience of children that adults make decisions about them without explaining why that decision has been made, asking what he or she feels about it or enabling them to influence that decision.

For some children, not being listened to can have a harmful effect on their health, as this quote highlights:

At school I got a sudden headache. I went to the nearby school but they ignored me thinking I was playing truant. When I went home to inform my mother, she was out. As my condition was getting worse I had to go to my sister. When I told her she took me to the hospital run by nuns who admitted me with serious malaria. My sister then called my mum to tell her I had been admitted. What would have happened if I did not have a sister? Since mum is at work, I could have died. Just because they ignore children.

(From the consultation undertaken in Tanzania for the development of this module)

When you recalled a memory of childhood, perhaps you remembered how vulnerable you felt when you had no control over what was happening to you. Maybe you felt upset because the nurse did not take account of your understanding of the situation. This might have meant she/he gave you the wrong treatment, or was unable to make an effective diagnosis. It might also have made you feel humiliated and frustrated. If a doctor or nurse imposed a treatment, for example, an injection, without discussing it with you or addressing your fears, you might have experienced more distress or pain than was necessary.

If the doctor or nurse explained what was happening to you, then you may have felt reassured and less fearful. They may have been particularly kind and spoken to you in a gentle way, encouraging you to be brave or telling you that the treatment would not hurt and that it would not be long before you could go back home. As a result, you may have felt valued, and even have positive memories of a time visiting a clinic or hospital.

All of us want to be respected and recognised when decisions are being made that have important implications for our health and well-being. This applies as much to children as to adults. It is important to remember these feelings when you are working with children: you can then respond to them as you might have liked to be treated when you were a child.

As health workers you need to put yourselves in the shoes of the children you care for in order to understand their feelings, anxieties and expectations. You can explain why you are making decisions and involve them in that process. They are then in a better position to understand the reasons for the treatment, are more likely to be open about their condition and symptoms, and are more likely to cooperate in any treatment.

1.4 What is child participation?

Participation is a process of being involved in decisions and actions that affect you. Children traditionally are denied this opportunity. However, this right to be heard and taken seriously is one of the fundamental values of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child and the African Charter on the Rights and Welfare of the Child. Of course, children have always participated in many ways within societies – for example, at the community level, through play and art, and in their economic contribution to their families. In the context of children’s rights, however, the term participation is now very widely used as a short-hand to describe the process of children expressing their views and having them taken seriously.

Participation can be defined as an ongoing process of children’s expression and active involvement in decision-making at different levels in matters that concern them. It requires information-sharing and discussion between children and adults based on mutual respect, and requires that full consideration of their views is given, taking into account the child’s age and maturity.

(Lansdown, 2011, p. 3)

It is important to understand that this does not mean that children should always have their own way, or that adults can no longer make decisions on behalf of children. What it does mean is that children can and should be involved in those decisions and have their views taken seriously, even if they cannot always be complied with.

Children can form and express views from the earliest age, but the way they participate, and the range of decisions in which they are involved, will necessarily increase as they grow older and more able. Young children’s participation will be largely limited to issues relating to their immediate environment within the family, care facilities and their local community. However, as they grow older and their capacities evolve, they are entitled to be involved in issues that affect them in the immediate family, in their community, their country, and even at the international level.

Study note

For ease in reading the text, from hereon we will be referring to the UN Convention and the African Charter.

Activity 1.2: Role play demonstrating a lack of child participation

If you are studying in a group you could conduct this activity as a role play. There are four characters, so you will need to have at least four people for a role-play activity. Otherwise you can read it and then consider the two questions that follow.

Background

A parent decides to take his or her daughter, aged 8, to the health clinic because they are worried that the child might have malaria. A health worker is available straight away.

Parent: Greets the health worker and explains that the child has a fever and headache.

Health worker: Examines the child silently and straight away prescribes medication without any discussion with the child. She also decides the child needs an injection and prepares to give the treatment.

Child: Sees the large needle and runs out crying to the reception area.

Receptionist: Asks what is the matter.

Child: Cries and says the doctor is going to give her an injection and she does not understand why. She is frightened.

Questions:

- What do you think about this situation?

- What would you do differently to permit the child’s participation? Act it out again, this time taking account of the child’s right to be heard.

Once you have acted it out again, note the points at the end of the session for Activity 1.2.

1.5 Four rights that promote children’s participation

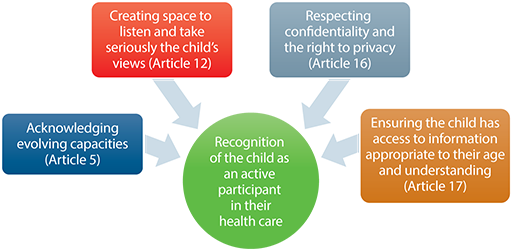

Some of the key rights that need to be understood in relation to the child as an active participant in their own health care are contained in Articles 5, 12, 16 and 17 of the UN Convention. Figure 1.1 below shows the relationship between the four articles and children’s involvement in their own health care. We will now move on to explain these four Articles in a little more detail.

Article 5: Acknowledging children’s evolving capacities

Article 5 recognises that parents have rights and responsibilities to provide guidance and direction to children. However, it also introduces boundaries on how those responsibilities are exercised. For example:

- Parents’ rights exist in order to protect children’s rights. For example, a child has a right to a name, so parents have the authority to give a child a name because a small baby cannot exercise that right for him or herself. Parents can give consent to medical treatment while the child is too young to do that for him or herself.

- Any guidance or discipline must respect children’s rights. For example, parents cannot impose punishments on a child that causes them physical, emotional or psychological harm. This means they should not punish a child by denying them food because this would abuse the child’s right to be as healthy as possible. Beating a child is also an abuse of their right to protection from violence.

- Parents should recognise that as children are able to exercise their own rights, then they should be increasingly allowed to do so. They should respect their child's evolving capacities (you studied evolving capacities in Module 1). In other words, parental rights exist until a child can exercise those rights for him or herself. After that, children should be allowed to take decisions for themselves. Children are not the property of the parents. The level of guidance and direction provided by parents should reduce as children acquire greater competence.

Children learn through experience and observation of what is going on around them. They develop their capacities to think and make decisions through guidance by the adults and other children around them. Constant mentoring and guidance as they grow through childhood enables them to develop their capacities.

Article 12: Listening to children and taking their views seriously

Article 12 of the UN Convention states that children have the right to be involved in all matters that affect them and to have their views taken seriously in accordance with their age and maturity. This applies to individual decisions such as their own health care. It also means that children as a group should be involved in matters that affect them, for example, how and what health care services are provided in their local community. The Committee on the Rights of the Child has identified Article 12 as a general principle that must be considered in the way all other rights are implemented. For example, in order to ensure that children’s right to health is fully realised, it is necessary that children are listened to and involved in their own health care. In order to ensure children’s right to protection from violence, they need to be listened to and taken seriously.

Children are entitled to make choices about whether or not they want to participate and to what extent. In relation to health care, for example, some children will want their parents to retain full responsibility for taking decisions. Some will want to share it with their parents. Others may feel that as it is their life and future at stake, it should be their responsibility to make choices for themselves.

My mum took me to the dispensary. I was afraid of the injection and wanted to run away. The nurse called some men who held me down by force. They hurt my chin but she didn’t care.

(From the consultation undertaken in Tanzania for the development of this module)

Article 16: Respecting confidentiality and the right to privacy

Article 16 of the UN Convention states that children have a right to privacy. This means that children are entitled to respect for privacy and confidentiality, for example, in getting advice and counselling on health matters, depending, of course, on their age and understanding. Governments are expected to introduce laws and regulations to ensure that older children are able to seek medical help in confidence. As a health worker, you need to know what the law says about keeping the medical information of older children confidential, and to protect that confidentiality as far as possible.

Confidentiality

Respecting confidentiality means that information is kept a secret. It means that information about the child, or things that the child has talked about should not be disclosed to anyone else unless the child agrees.

Respect for confidentiality is important as young people are likely to avoid seeking medical help if they fear either that they will not be seen without their parents or, that if seen alone, their parents will be notified. Clear and well-publicised policies that confidentiality will be respected will encourage children to approach a nurse or doctor. They should then feel free to discuss their situation more frankly and explicitly than might otherwise be the case. The outcome will certainly be better access to health care and earlier interventions to promote good health. There are many circumstances where the principle of respecting confidentiality is of crucial importance to children’s safety, well-being and dignity.

They maintain confidentiality for common diseases. But for STIs, no confidentiality. You can go to the dispensary to be treated and then you find that after a few days, people know what was your problem and even the meds you were given.

If I go to the dispensary on my own, my parents should not be told without my permission. Some sicknesses are my private affair.

(From the consultation undertaken in Tanzania for the development of this module)

Article 17: Ensuring that the child has access to age appropriate information

Children can only make meaningful decisions if they have access to relevant information. As a health worker, you can play a key role by ensuring that children have appropriate information to help them make healthy choices in their lives. For example, information on how to keep healthy, how to avoid risks, information about sexual and reproductive health and HIV/AIDS, illegal drugs and alcohol, diet and nutrition. You could be involved, in collaboration with young people, in developing preventive and promotional materials on health to disseminate within your local community. If children are ill, you need to provide them with information about the nature of the condition, the symptoms, the treatments needed, the implications of those treatments, and how to avoid further problems. Such information enables them to appreciate the importance of the decisions they make and empowers them to make safe choices in the future.

We are told what the meds are for what but never ever been told about side effects.

Doctors don’t want to be being asked questions. They say: ‘Who is the doctor, you or me?’

We are never given the chance to ask.

(From the consultation undertaken in Tanzania for the development of this module)

Activity 1.3: Participation in the African context

Read the article below (adapted from Lansdown, 2011, p. 17) and then answer the two questions that follow.

If you are working in a group discuss your opinions afterwards..

Understanding participation in the African context

Participation of children as stated in the Articles of the UN Convention is sometimes seen as foreign, superficial and alien to the African culture. In any discussions on participation of children, it brings out political, cultural, social and emotional concerns and divides. It can be viewed as a threat to parental authority, and an intrusion on the authority of the family head in particular.

In the past, many African traditions encouraged child participation without realising that they were doing so – making it possible for children to access useful information and contribute to decisions. Sitting round the fire, sharing folklore, stories and songs, elderly people gave children the opportunity to participate actively. This included questions and answers, the sharing of opinions and personal interpretation of the messages in a story. Dances within the community also prompted discussions around cultural practices and morals. While some of these forums had negative aspects such as encouraging stereotyping, early marriage and the subordination of women, they nevertheless did solicit the views of children.

While child participation has been practiced in the African context for decades, this form of participation in traditional African society is beginning to disappear because modern-day living has led to the loss of these practices.

These days, while many adults believe that children have rights to life, health and education, many are not convinced that children have the right to participate in decisions affecting them, their family or their community. Child participation is often restricted because African family relationships can be divided into categories with role expectations clearly defined. In some communities children are not allowed to speak among adults without permission as doing so may bring disgrace on the parents.

Children’s rights are enshrined in the UN Convention, which was developed outside East Africa. However the Convention has been interpreted and incorporated into the African Charter on the Rights and Welfare of the Child, which has been accepted by African governments as good principles for all African countries (Ministry of Gender, Labour and Social Development, 2008).

Questions

- What can you learn from this article?

- How could you use positive traditional practices to enhance children’s participation in your country or community?

Discussion

- This article suggests that children’s participation is often viewed as an imposition from outside African culture. It is seen as an alien concept that challenges traditional ways of relating to children. However, you will also have learned that, in fact, many traditional practices in Africa did involve listening to children. Story-telling, sharing traditions, sitting together around the fire, all provided opportunities for children to talk with elders and share experiences. What is missing is a way of linking these traditional practices with the modern language of the UN Convention. The article highlights the fact that there is no real conflict between the values of the Convention and African culture. The similarities between the UN Convention and the African Charter provide evidence of the compatibility of the values.

- You could begin to think about traditional practices within your own community that might have involved children, and then explore how they might be used to help strengthen understanding of their value and how they might be applied in the current context of children’s lives. For example, in some communities, children and young people have expressed concern that traditional rites of passage such as male circumcision place boys’ health at risk, particularly in areas where there is a high rate of HIV/AIDS. Instead of ignoring those concerns, it may be possible to bring different members of the community together in a ‘circle’ to discuss the issues. Some elders may feel it is threatening to their culture and authority to change these traditions whereas young people may feel it is more important to stay healthy than to preserve traditions. By bringing generations together to listen to each other, it may be possible to find a way of maintaining the important rite of passage but doing so in a way that is safer and does not place boys at risk.

1.6 Why is child participation important?

Participation is not only a right of every child, but it also brings with it many positive benefits for children themselves, including to their health and well-being. It can also make the work of the health worker easier:

- Involving children in their own health care makes children feel more respected. And when children feel that they are respected, listened to and that their views are valued and taken seriously, this helps reduce the vulnerability associated with being ill, in pain and dependent on others.

- If you listen to children, it will help you understand the child’s condition better, and this will help you treat them more effectively.

- Being listened to helps relieve anxiety and enables children to cope better with treatment.

- If children have information about their condition, they are better able to understand and address what is happening to their bodies and why things are happening the way they are.

- It gives them confidence. If children are involved in the process of treatment, they will not have fears that actions will be taken without their knowledge or understanding.

- It encourages co-operation. If children lack information, they are likely to be more frightened and therefore less willing or able to co-operate in treatment which, in turn, makes interventions more painful and distressing.

- It avoids unnecessary distress. When information is withheld, children may worry unnecessarily about what is going to happen to them.

- Often the imagined risks are far worse than reality. If they have information, children can prepare appropriately for what is happening and receive necessary counselling, comfort and support.

- Children develop a better understanding of their own health care needs.

- It encourages them to take more responsibility for their own health because they develop a better sense of the causes and consequences of their actions or inactions.

1.7 What are the challenges to participation and how can we address them?

There are a number of challenges to making sure children are listened to by health professionals. As we discussed earlier, in many countries and cultures, including in Africa, there is a considerable resistance to the idea that children and young adults have to be consulted and listened to. It runs counter to the assumption that adults know best and that children lack the experience and competence to take responsibility for decision-making. Many parents and professionals are also concerned that providing children with information about their medical condition might be painful for them to accept. They argue it is better to protect children from such information and choices. The following discussion looks at five particular challenges and provides some ideas on how to address these.

1.8 Capacity to participate

Are infants capable of expressing their views? If so, how?

What about a child who cannot communicate verbally? How can you acknowledge and respect the views of these children?

Even very small children can tell you what they like or dislike about being in hospital and can produce ideas for making their stay less frightening and distressing. Provided they are given support, adequate information and allowed to express themselves in ways that are meaningful to them, all children can participate in issues that are important to them. This can be through pictures, poems, drama, photographs, as well as more conventional discussions, interviews and group work.

In the case of babies, their lack of speech should not be an obstacle to considering and respecting their point of view and feelings. For example, they can express their feelings of distress, fear, distrust, or comfort through facial expressions, body language, crying and smiling. A health worker can use this information to identify needs such as the need for a nap or a feeding, responding to whether or not they are in pain. It is important for health professionals to establish a positive relationship with a baby and his or her parents and involve them during the consultation or treatment.

Some children with disabilities, such as children who are hearing or visually impaired, or those that have autism, may experience difficulties in communicating verbally. It is equally important to explore approaches that allow them to express their views. Parents and caregivers will often be able to advise on how to communicate effectively with disabled children.

All children have the capability of expressing their views. Therefore it is necessary for health professionals to explore the many ways that enable the child to articulate these views, concerns and opinions.

1.9 Assessing competency

Should the views of a six-year-old be given the same weight as the views of a 16-year-old?

At what age are children competent to take responsibility for their own health care?

What defines competence?

Obviously children at different stages of development will have differing capacities to take responsibility for their own health care, although these capacities are not necessarily defined just by age. Children’s capacities are highly dependent on the experiences they have had. For example, young children who have experienced major surgery or frequent medical interventions may have a profound understanding of life or death and how decisions will affect them. There are two distinct issues to consider here.

- All children can be involved in decisions about their health care, even though the actual decisions will be taken by adults. For example, while five-year-old children may lack the competence to decide that they need to go to hospital for an operation, they can indicate if and why they feel comfortable at the hospital, and provide suggestions to improve their stay.

- Some children will have the capacity to give formal consent to their treatment or to refuse treatment, although the legal rights to do so will be determined by the legislation in any given country. You need to know what the law says in your country. Considerations to take into account in assessing children’s capacities to give or refuse consent can include:

- Is the child able to understand and communicate relevant information? The child needs to be able to understand the alternatives available, express a preference, express concerns and ask relevant questions.

- Is the child able to think and choose with some degree of independence? The child needs to be able to exercise a choice without coercion or manipulation and to think through the issues for themselves.

- Is the child able to assess the potential for benefit, risk and harm? The child must be able to understand the consequences of different courses of action, the risks involved and the immediate and long-term implications.

In general, health professionals need to listen to children, provide appropriate information and give them time to articulate their concerns, so that children can develop the confidence and ability to contribute effectively to their own health care.

1.10 Child participation: obligation or burden?

Do children have an obligation to express their views?

Does giving children rights to be heard burden them unnecessarily?

Neither the UN Convention nor the African Charter imposes obligations on children to express their views. Rather, they provide a right for the child to do so. Children should be given the opportunity to participate and express their views if they so choose, and be helped to do so.

The assumption that children will be burdened unnecessarily is rooted in a view of childhood that imagines children and adolescents do not take decisions or responsibilities at very early ages. However, even small children can act responsibly, for example, in caring for younger siblings, coping with parents in conflict, deciding on what games to play, and negotiating rules. Listening to the views of children, and supporting their participation in a way that respects their evolving capacities teaches children to listen and respect the opinions of others, clarify their own opinions and make decisions about their lives.

1.11 The right to protection versus the right to privacy

Should a child’s right to protection from violence, abuse or neglect override their right to privacy and confidentiality? If so, when?

All rights are inter-dependent. However, at times there can be a tension between different rights. For example, it may be the case that in order to protect a child from serious risk of abuse, it is necessary to override their right to privacy. Depending on the laws and regulations in your country, health care professionals may have an obligation to report cases of abuse and neglect, even where the child is adamant that he or she does not want the information to be taken further. In such circumstances, it is important to be clear with the child about the boundaries of confidentiality, what the law says, and to involve the child as far as possible in deciding how and when the information will be reported. It is important to remember that violence and abuse of children disempowers them. The strategies adopted to protect them should not further disempower them. Any action must take account of the child’s individual circumstances and contexts. A ‘one size fits all’ approach should never be adopted.

1.12 Lack of respect for parents

Does participation lead to disrespect?

Will it undermine parental authority?

Listening to children is about respecting them and helping them learn to value the importance of respecting others. It is not about teaching them to ignore their parents. Indeed, the UN Convention states that education should teach children respect for their parents. Listening is a way of resolving conflict, finding solutions and promoting understanding – these can only be beneficial for family life. It can be difficult for some parents to respect children’s rights to participate when they feel that they, themselves, have never been respected as subjects of rights. This does not imply the need to retreat from encouraging children to participate but, rather, the need to be sensitive in doing so. Children should not be led to believe they alone have a right to have a voice; wherever possible, their families should be involved too.

Activity 1.4: Involving children in health care decisions

Think about a situation where you have had a difficult decision to make in your practice. You may have had to override the wishes of a child or his or her parents by insisting on a treatment, or you may have had to breach confidentiality or report an incident. What did you decide to do and why?

If you are unable to identify a case from your own practice, you could think about what you would do for one of the following examples:

- a.A 13-year-old wanting contraception but does not want her parents to be informed. Should her privacy be respected?

- b.An 8-year-old child has HIV, which was transmitted from the mother. Should the child be told even though the mother does not want this?

- c.In a school vaccination programme should individual children be consulted and asked to give their permission?

Now, for your own situation or one of the examples above, consider these questions:

- Would you create time to explain what was happening to the child or would you simply provide information to the parents?

- How would you determine whether the child is competent to make a decision about his or her health care?

- When would you breach a child’s privacy?

If you are working in a group - discuss and debate your experiences and responses.

Discussion

There are no right and wrong answers to these questions. However, there are some issues that it would be useful for you to consider when faced with such cases.

- Some of the negative implications of providing information to the child are that it would take time, it might cause the child distress, and the parents might object. Some of the benefits are that the child might be less anxious, feel more in control, and be better prepared for what is happening. In addition, the child might be more able to co-operate and better able to talk about problems if she or he knows what is happening. Parents would also be better equipped to help the child where there is openness and honesty.

- You could check their level of understanding about the kind of treatment being proposed and its implications. You could make time to talk with the child about their feelings and views and why they are concerned about the treatment proposed or the request for confidentiality. You could assess the child’s ability and competency as an individual and try to avoid assumptions based on their gender or age.

- On the one hand, you may feel it is necessary in order to ensure that a child gets the treatment he or she needs, or in order to ensure their protection. On the other hand, there is a danger that if children feel the health worker will not respect confidentiality, they will not seek help when they need it. This may cause even more harm to the child. As a general guide, you should always respect a child’s privacy unless it is in the child’s best interests not to do so, or where the law requires you to breach privacy.

1.13 Summary

The aim of this study session was to introduce you to the right of children to be active participants in decisions and actions that affect their lives. The key points it addresses are as follows:

- Participation is a process of being involved in decisions and actions that affect you. Despite historical traditional practices that encourage children’s participation, children are often denied this opportunity. However, this right to be heard and taken seriously is one of the fundamental principles in the UN Convention and the African Charter.

- In the field of health care, the right to participate is addressed in four key articles in the Convention: the right to respect for evolving capacities, the right to information, the right to express views and have them taken seriously, and the right to privacy and confidentiality.

- Participation is not only a right but also carries significant benefits for children. It leads to better decisions, it builds their confidence, it reduces fears and anxieties, and it helps children to take on the responsibilities they will have in later years. The health worker benefits too, as children will be more likely to communicate more effectively with the health worker and to cooperate in treatment.

- Many adults have concerns about letting children participate. For example, they worry that children lack capacity or that it will erode parental authority. On the contrary, participation serves to enhance children’s lives and can strengthen relationships between adults and children. Of course, children should never be forced to participate against their will. It is a right not an obligation.

1.14 Self-assessment questions

Question 1.1

List three benefits of children’s participation to children themselves and three benefits to the health worker.

Question 1.2

What do you understand the term ‘evolving capacities’ to mean, and how is this relevant to children’s participation in health care decisions?

Question 1.3

Name three objections you might hear about children’s participation and state how you might challenge these objections.

Question 1.4

Having completed this study session, identify two things that you will do differently in your practice to involve children in decisions that affect their health?

1.15 Answers to activities

Activity 1.2: Role play demonstrating a lack of child participation

- The problem for the child in this scenario is that she has no idea what is happening and why. No-one has bothered to explain to her what is the matter with her and what treatment is necessary to help her to get well.

- If you were the health worker, you could explain to the child that she is ill, what is the matter with her and how having the injection will help her recover. You could give her reassurance about having the injection, for example, you could ask her if it would help if she sits on her parent’s lap and holds their hand. You could explain where you will give the injection and how she will feel afterwards. This way, she may be less frightened. Having an injection may be less painful and distressing if the child has a little more control over how it is delivered and is comforted and supported. You might also involve the parents, explaining to them why it is important to reassure the child and listen to their concerns.

2 Best interests of the child and non-discrimination

Focus question

How should we act to ensure the best interests of children and prevent discrimination?

Key words: best interests, competing interests, direct discrimination, inclusive services, indirect discrimination

2.1 Introduction

In the first study session of this module, we discussed the principle of children as active participants. Children have a right to be involved in the decisions made by adults on their behalf. In this session, we explore the right of children to have their best interests given consideration when adults are making decisions about them, as well as the right not to be discriminated against.

Both the UN Convention and the African Charter emphasise the importance of best interests and non-discrimination. These are two of the guiding principles you studied in Module 2. This session will explain what these two rights mean, their implications for you as a health worker, and will provide guidance on how to apply them in your day-to-day practice

2.2 Learning outcomes

At the end of this study session, you will be able to:

- define and use correctly the key words above

- explain the principle of best interests of the child as it applies to the provision of health services to children

- explain the principle of non-discrimination as it applies to the provision of health services to children

- understand how to make decisions that are in children’s best interests in your practice.

2.3 What is meant by ‘best interests of the child’?

The concept of the ‘best interests of the child’ is a central building block and a guiding principle of both the UN Convention and the African Charter. It means that when any decision or action is being taken that will affect a child, you need to think about whether it is in the best interests of that child.

In all actions concerning children, whether undertaken by public or private social welfare institutions, courts of law, administrative authorities or legislative bodies, the best interests of the child shall be a primary consideration.

(From Article 3, United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child)

In all actions concerning the child undertaken by any person or authority the best interests of the child shall be the primary consideration.

(From Article 4, African Charter on the Rights and Welfare of the Child)

The Committee on the Rights of the Child has interpreted Article 3 as applying both to children as individuals and as a group. For example it applies to a child’s specific health condition and care, and it applies to decisions affecting groups of children, for example, policies on health or welfare. To give an example, if you are deciding to give a child a particular treatment, you must be sure it is in their best interests to do so. Equally, the way in which your clinic or hospital ward is organised should take account of the best interests of children rather than the convenience of the administrators or doctors.

It is important to understand the weight that should be given to the best interest principle. Article 3 of the UN Convention and Article 4 of the African Charter require that the best interests of the child is a primary consideration. This recognises that other interests can be considered, but that the child’s interests are the most important interests. The scope of the article is extremely wide, covering all actions concerning the child or children.

2.4 How to determine the best interests of a child

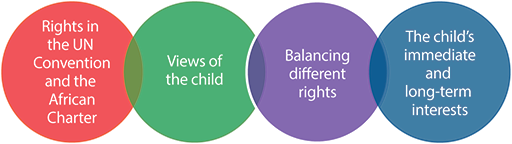

There are four aspects you can consider in determining the best interests of a child. These are shown in Figure 2.1 below.

These aspects are interlinked and can be used in any situation where you want to determine the best interest of a child or children.

Rights in the UN Convention and the African Charter

The overall goal of the UN Convention and the African Charter is to promote children’s best interests. The starting point in defining the best interests of the child, therefore, must be to make sure that all their rights are fully realised. Both treaties also make clear what is not in children’s best interests, for example, exposure to all forms of violence, sexual and economic exploitation, harmful traditional practices, and discriminatory laws, policies and practices. Together they provide an important guide to help you assess whether a decision or action may be harmful to a child’s best interests.

Views of the child

The views of the child must be taken into account in determining what is in their best interests. A child’s age, maturity and capabilities are important factors in the weight given to the child’s views, but children of all ages and abilities should have an opportunity to have their views considered. Too often, adults decide what is best for a child without any reference to the child’s experiences or concerns.

Balancing different rights

Determining the best interests of the child also requires you to think about the different rights children have and how they are taken into account with each other. For example, a child requires a stable family environment, but if the child is experiencing harm or neglect in the family home, it may not be in their best interests to stay with their own family. The disruption to the child's life may be necessary in order to protect them. Situations can arise where rights appear to conflict. For example, a competent teenager may exercise his right to refuse treatment, whereas medical opinion considers that the treatment is vital for his long-term health and well-being.

The child’s immediate and long-term interests

Consideration must always be given to both short- and long-term best interests of the child. A child that is at risk of harm or neglect may need to experience temporary disruption to their lives while they are moved to a safe location. However, in the long term this may prevent them from further harm and improve their opportunities in life.

There are no easy answers to such complex dilemmas, but a commitment to the best interests of the child provides a mechanism to help determine how to reconcile tensions, and ensure the realisation of children’s rights.

Activity 2.1: Acting in the best interests case study

Read the case study below, keeping in mind the four interlinked aspects introduced above in section 2.4.

If you are working with another person or in a group, discuss the questions below. Otherwise, try to answer the questions yourself before reading further.

Asha, aged 11 years, has had a history of continued ailment and, because of limited facilities, it took four years to diagnose her illness as leukemia. She has undergone numerous procedures that have controlled the spread of the cancer but these treatments have resulted in secondary complications including a hole in her heart. Her medical advisers say that to reach adulthood she will need a heart transplant but they cannot predict that this will be successful. Asha has said that she has had enough of medical procedures and does not want the transplant. She is supported by her parents. The doctors insist that they should proceed.

- What rights does Asha have in this situation?

- What are Asha’s views?

- What other needs does Asha have?

- What are Asha’s short- and long-term interests?

- In your view, are the doctors right to insist on this treatment?

Discussion

- You may have identified a number of rights that Asha has. She has a right to survival, a right to appropriate health services, and a right for her views to be taken into consideration. These rights are contained in both the UN Convention and the African Charter.

- Asha does not want to be operated on. She has undergone numerous procedures already and may be distressed by the thought of further medical intervention. Her experience to date may have given her a negative perception of medical facilities.

- Agreeing to Asha’s preference may be detrimental to her well-being. In this situation it may lead to further serious illness or even death. In such cases, the health worker, parents, or others, might have to help the child understand the effect of their decision and the advantage of taking the operation.

- Asha’s most immediate interests are to prevent distress and upset, but her right to survive is of greater importance. Consideration has to be given to her evolving capacities to take responsibility for decisions that will affect her future. You would need to decide if she genuinely understands the implications of the choices that need to be made.

- From the limited information available to you, it may not be possible for you to say with certainty whether the doctors made the right decision. They can consider Asha’s views and respond sensitively, ensuring that Asha understands the importance of the operation. They want to give Asha the best medical care to ensure her survival and they are willing to override her views and that of her parents if necessary to achieve this best interest. However, if the operation would be likely to cause significant distress and physical pain both during and afterwards, and was expected to prolong life for only a very short time, would the doctors still be right to insist? While the right to life is vitally important, the quality of life is an important factor to consider when making decisions in health care.

In determining the best interests of the child, there is often no easy right or wrong answer. Rather, consideration of the best interests can be a way of resolving difficult dilemmas and making judgments in complex situations. It provides a guiding principle to help you in those circumstances.

2.5 Competing rights and interests

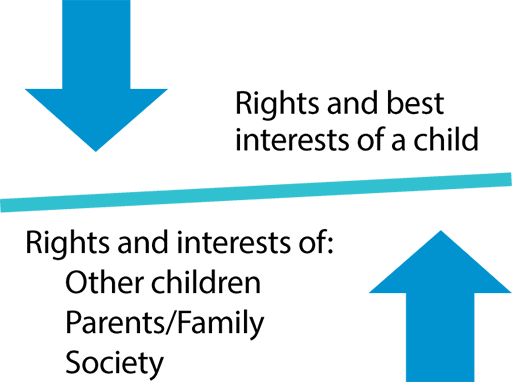

So far, we have considered how children’s rights law, children’s views, children’s holistic needs and children’s short- and long-term interests help to determine what is in a child’s best interests. Sometimes, the rights and interests of other children, of parents and families, and of wider society, also need to be balanced with the rights and best interests of a child (see Figure 2.2).

Balancing the interests of a child with other children

Situations will arise when ensuring the best interests of one child or a group of children may not be in the interests of other children, and vice versa. For example, health workers might need to respond to a particular epidemic, which might affect other children and adults. They cannot decide to use a particular child for experiments so they can get a remedy to treat the disease and save many other children. Instead they have to identify other strategies that do not compromise the best interest of the child. By contrast, even though an individual child has a right to education, if she or he is continuously disruptive and behaving badly, they may need to be excluded from school for a while so that other children can learn.

Balancing the interests of a child with parents and family

Most parents will have their children’s best interests at heart. However, it cannot be assumed that this will always be the case. There are times when the interests of children and parents can be in conflict. For example, a parent may wish to arrange for a teenage girl to be given a contraceptive injection to prevent her getting pregnant. However, the girl may strongly object to having the injection, perhaps because she is frightened of injections or because she feels it is a sign of her parents not trusting her.

Although the UN Convention and the African Charter fully recognise the importance of parents in children’s lives, and respect their rights and responsibilities towards their children, it also stresses that children have rights and that it cannot simply be assumed that parents will always act in the best interests of children. Where children’s rights are placed at risk by their parents, the best interests of the child must always come first. Where parents abuse or neglect their children, for example, or discriminate against girls. Health professionals need to ensure that this principle underpins all services, procedures or policies, which they are responsible for implementing.

Activity 2.2: Balancing best interests of a child with the interests of the parents

Think about the example described above – a parent forcing a girl to have a contraceptive injection.

If you are working with others on this curriculum, break into two groups with one group taking the side of the parent and the other taking the side of the girl. Then construct a role play arguing out the scenario. What arguments might you bring to support each position?

After the role play, discuss in plenary whether you think it is in girls’ best interests when parents force them to have contraceptive injections to prevent pregnancy while they are still at school?

Compare your answers to those at the end of the study session.

Balancing the interests of a child with wider society

It is sometimes proposed that the interests of the community or the society must take precedence over those of an individual child. For example, where the maintenance of traditional cultures is sometimes seen to be more important than the rights of an individual child who may be harmed within that culture. However, these arguments cannot be used to override the rights of a child. Nor can it be argued that children’s best interests are served by cultural practices, which deny rights that are now guaranteed in law. For example, it is not acceptable to claim that because a particular culture has always beaten children to instil discipline, their best interests are served by its continuation. Similarly, female genital mutilation cannot be defended as a traditional practice serving girls’ best interests by enhancing their marriage prospects, or maintaining the values of the wider community. It clearly represents a rights violation, and is contrary to the child’s interests in terms of health, survival, emotional well-being, dignity, and protection from violence and harm.

A commitment to the best interests of the child demands that health services adopt explicit policies to protect and promote the rights of children above those of their communities when those rights are in conflict. Of course, the way in which this is done needs to be sensitive to the concerns of that community and, wherever possible, explore approaches, which can be accepted by the majority of its members.

Can you recall a situation where you have had to deal with competing needs, interests or claims? How did you deal with the situation?

Now that you have learned more about the best interests of the child and managing competing rights and interests, would you deal with it any differently if something similar happened again?

No easy answers can be provided when there are legitimate competing claims. When assessing the best interests of the child and children generally, it is a case of sensitively assessing and comparing different views and different degrees of actual or potential benefit and harm.

2.6 Assessing best interests and competing interests in practice

Activity 2.3: Assessing best interests and competing interests in practice

Read the case study below.

Achen is a 14-year-old girl who goes to see her doctor saying she is getting headaches. During the course of the consultation, she breaks down and says that her father is sexually abusing her. However, she does not want you to do anything or tell anyone. She feels that it will cause more problems. She does not think her mother will believe her, and then she will be even more isolated and unhappy than she is now. And if action is taken against her father, it will destroy the family and her mother will blame her.

- What factors do you need to consider in weighing up Achen’s best interests? Use the table below to write in the factors you need to think about, which include factors relating to Achen’s best interests and the interests of others. Some suggestions have been filled in to get you started. You do not have to complete every box in the table, but try to fill in at least five more suggestions.

| Rights and best interests of a child | Interests of other children | Interests of parents/family | Interests of wider society | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rights in the UN Convention and African Charter | Children have a right to be protected from all forms of violence | Governments should ensure children are protected from violence and abuse | ||

| Views of the child | Achen is worried about the impact on her family | |||

| The child’s other needs | Achen may provide support in the home which includes looking after younger children | |||

| The child’s immediate and long-term interests | Taking visible action in one case may deter others from committing offences |

- Once you have added at least five more suggestions of factors you need to consider, look at all the information in the table, comparing different degrees of potential benefit or harm. In this situation, what action will be in Achen’s best interests?

Compare you answers with the table at the end of the study session.

2.7 What is meant by ‘non-discrimination’?

Human rights apply equally to every child. No child must be discriminated against on any grounds. For example, it is not acceptable to say that the right to education for children with disabilities is less important than for other children. It is also not acceptable to allow different levels of funding for services for one ethnic group over another. Children who are stateless or refugees or asylum seekers have exactly the same rights as any other child – the right to food, shelter, education, and protection, for example.

Discrimination can be defined as any distinction, exclusion, restriction or preference which is based on a particular ground such as race, colour, sex, language, religion, political or other opinion, national or social origin, property, disability, birth or other status, and which has the purpose or effect of removing or harming the recognition, enjoyment or exercise by all persons, on an equal footing, of all human rights and freedoms.

(United Nations, 2009)

The articles in the UN Convention and the African Charter place a clear obligation on governments to respect and ensure the realisation of all rights to all children without discrimination on any grounds.

State Parties shall respect and ensure the rights set forth in the present Convention to each child within their jurisdiction without discrimination of any kind, irrespective of the child’s or his or her parent’s or legal guardian’s race, colour, sex, language, religion, political or other opinion, national, ethnic or social origin, disability, birth or other status.

(From Article 2, United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child)

Every child shall be entitled to the enjoyment of the rights and freedoms recognized and guaranteed by this Charter irrespective of the child’s or his/her parents’ or legal guardians’ race, ethnic group, colour, sex, language, religion, political or other opinion, national or social origin, fortune, birth or other status.

(From Article 3, African Charter on the Rights and Welfare of the Child)

2.8 Different types of discrimination

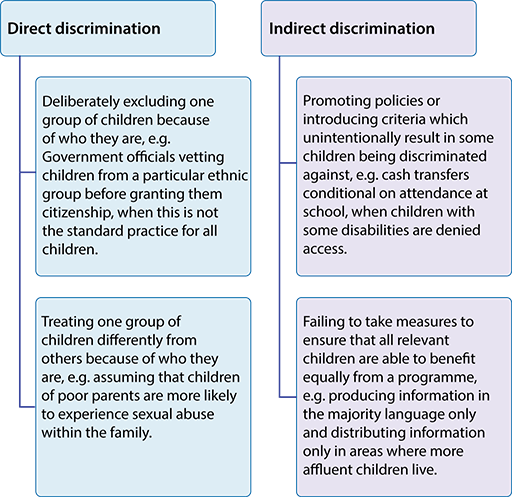

Discrimination can occur at any level in a society. It can be practiced by governments, by adults against children, by one community against another, or one group of children against another. It can arise from active, direct and deliberate actions, or it can take place unconsciously through insensitivity, ignorance or indifference. These two types of discrimination that arise from either deliberate action or indifference are called direct and indirect discrimination (Figure 2.3). It is important that you understand the difference because they need to be tackled in different ways.

Direct discrimination

This occurs when an action, activity, law or policy deliberately seeks to exclude a particular group of children. In some countries, for example, children with disabilities are classified as either ‘educable’ or ‘non-educable’, the latter being denied the right to education. In many countries, the marriage age, and that of sexual consent, is lower for girls than boys, and children born outside marriage are denied equal rights. Legislation can also discriminate against all children as a group – for example, laws that permit children to be subjected to assault through physical punishment, when the same assault against an adult would constitute a criminal offence. In a recent consultation carried out in Tanzania for this module, young people repeatedly commented that nurses would treat children nicely when they were private patients, but would be rude and disrespectful to others, a clear example of discrimination against poorer children.

Indirect discrimination

This occurs when an action, law or policy has the consequence of excluding or harming particular groups of children, even if that was not its intention. For example, holding clinics in areas where there is no public transport may result in discriminating against poorer children. A health facility would discriminate indirectly against some children with disabilities if it was based in a building that they find difficult to get into. Young people in Tanzania described examples of children with disabilities being removed from health care lists, and a total lack of any attempt to provide accessible facilities, such as ramps or adapted toilets. Without these adaptations, children with disabilities are indirectly discriminated against in their right to health care.

Multiple discrimination

Discrimination can occur on more than one ground, for example, relating to both age and gender, or to both language and cultural background. To give an example, a girl may experience discrimination because of:

- her gender, including low status within her family

- a reluctance to send her to secondary school

- an expectation that she will do domestic chores

- vulnerability to physical and sexual violence.

If she also has a disability, she may suffer further discrimination. A very common form of multiple discrimination arises when children of poor parents also belong to an ethnic or religious group that is already excluded or treated differently. Poverty and other types of discrimination can work together to reinforce exclusion.

2.9 Treating children according to their needs

The principle that children should not be treated differently does not mean that all children must be treated the same. This may seem like a contradiction, but it simply means it is acceptable and appropriate to provide different responses to different children if they have different circumstances and needs. For example, a child with a disability may require a particular service or may require extra time to assess their condition during a medical examination, particularly if they are unable to communicate their needs as well as other children. It would not be appropriate to give all children this extra time because they do not need it. This difference in treatment is very similar to the principle we discussed earlier – the best interests of the child. Different treatment is appropriate when it is in the child’s best interests.

Compared to other children, what specific services might an eight-year-old girl who is a wheelchair user need when attending a clinic?

Are there particular physical, communication or attitudinal barriers that might be encountered?

2.10 Who is protected from discrimination?

If you look back at the box that contains the Articles from the UN Convention and the African Charter, you will see that in the Articles on discrimination there is a list of categories of children who are entitled to protection from discrimination. Children are often discriminated against because of their own or their parents’ or guardians’ race, colour, sex, language, religion, political or other opinion, national, ethnic or social origin, disability, fortune or birth status. That is why these categories are specifically listed in the UN Convention and the African Charter.

However, it is important to note that both the UN Convention and the African Charter include ‘or other status’ at the end of the list of categories. Human nature is such that people will continue to find ways of including or excluding groups of people based on distinctions in how we look or sound, our history and how we behave. The Convention and Charter are clear that no category of distinction permits the denial of any child’s human rights.

Activity 2.4: Children that are particularly at risk of discrimination

Think about the work that you do in your health facility or other place of work.

Are there particular categories of children you see that might experience discrimination and are therefore be in need of protection against discrimination? Try to identify at least three categories of children that are particular to your country or locality.

For each category you have identified, how might discrimination occur? Can you say whether this discrimination is direct or indirect?

Discussion

Your list might include children with disabilities, street children, children from some ethnic backgrounds, children from families of particular religious groups, or girls and young women.

If you thought about street children, a specific issue is that they could be refused access to a health centre because they are unwashed. The policy to stop unwashed children from entering the health centre will result in indirect discrimination against street children, preventing them from accessing health services that are important to their needs and the fulfilment of their right to health.

In some East African countries, a category of children that are particularly at risk is albino children, who have a genetic condition that causes a deficiency of melanin pigment in the skin, hair and eyes, resulting in a pale complexion and little protection from the sun’s ultraviolet rays. Many albino children in East Africa continue to be feared and even murdered for their body parts which are used in medicine believed to cure a wide variety of ailments. Albino children in Tanzania are often forced into exile. This form of extreme treatment is direct discrimination, denying children their right to security, to a family life and the right to participate in the community.

2.11 Applying the principle of non-discrimination in health care

It is important to go beyond an approach that relies on an absence of direct discrimination towards any particular group of children. Ensuring that a service is not discriminatory requires a pro-active analysis of what the service does, how it does it, and who it does and does not include. Consideration can also be given to targeting services towards the most marginalised or vulnerable children. This means designing programmes that explicitly tackle under-representation or exclusion.

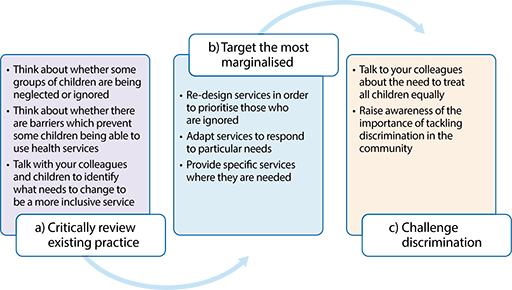

The approach shown in Figure 2.4 may help you to review your existing practice or practices in your place of work. It goes beyond preventing discrimination and encourages a pro-active approach to creating an inclusive service that meets different needs, ensuring that all children can realise their rights.

By taking action to prevent unfavourable treatment, to challenge discrimination and to meet different needs, you will be creating an inclusive health service.

Discrimination against children on the grounds of, for example, disability, gender and colour exist in all societies to varying degrees. Some types of discrimination have been identified as particularly serious issues in East Africa. Girls are discriminated against in many ways; for example, if a girl gets pregnant, is the attitude to her the same as it is to the boy who is the prospective father? Also, do girls get the same access to reproductive health care advice as boys?

As you reflected on your work place, you could no doubt identify many examples of discrimination that you have seen. In your health care practice, you may have seen children with disabilities getting a much poorer response from parents or fellow practitioners because they do not feel that their life is of equal value to other children. Perhaps a child with a disability has been refused services on the grounds that their quality of life does not justify intervention. The physical structure of the building or the toilets may prevent some children with disabilities from using the health facility in the first place.

As a health worker, now that you are becoming familiar with the UN Convention and the African Charter, part of your role needs to be in countering this discrimination in the workplace. You can work to ensure that children with disabilities get the same treatment as other children. You could also challenge attitudes and behaviour that are directed towards girls and make sure your own practice is informed by a commitment to children’s rights and non-discrimination.

2.12 Summary

- In all actions concerning a child or children, the best interests of the child is a primary consideration, meaning that it has added weight when weighing the interests of the child against other interests.

- Four different aspects can be actively considered to help you to assess what is in a child’s best interests:

- implementing all children’s rights

- taking account of the views of the child

- balancing different rights

- looking at the short- and long-term interests of the child.

- Children have a right to experience their lives free from discrimination on any grounds.

- There are two main types of discrimination. Direct discrimination arises from active, direct or deliberate action, and indirect discrimination arises from indifference to the needs of particular groups in society.

- In applying the principle of non-discrimination, it is essential to go beyond an approach that simply aims to avoid direct discrimination. Consideration can be given to ensuring the most vulnerable children in the community have access to services and that specific services are set up to meet the needs of particular groups of children.

2.13 Self-assessment questions

Question 2.1

Define what is meant by:

- The principle of the best interests of the child.

- The right to non-discrimination.

Question 2.2

Give three examples of issues to consider in determining the best interests of the child in any particular situation.

Question 2.3

Describe the difference between direct and indirect discrimination.

Question 2.4

List three groups of children who might be discriminated against in your place of work and provide some examples of action that could be taken to address the discrimination

2.14 Answers to activities

Activity 2.2: Balancing best interests of a child with the interests of the parents

- The parents might argue that many girls of her age are getting pregnant, and that it is very easy to get involved in sexual relationships even if you did not really intend to. They want to protect their daughter from getting pregnant and losing out on schooling. They also worry about the stigma of a teenage pregnancy. They might argue that even if the girl does not choose to have a sexual relationship, many girls get sexually assaulted, so can get pregnant against their will. Their view may be that overall, it is better to be safe than sorry. The risks are too high so it is better to be prepared.

- The girl may argue that her parents are showing a total lack of trust in her and undermining her right to make her own choices. She may argue that she has no intention of getting into a sexual relationship, that her education is far too important to her to take such a risk, and that her parents should have a higher opinion of her. She may also feel that the argument that she might be assaulted is a terrible reason for having the injection. If they think she is at risk of being attacked, they should act to protect her not simply act to prevent a pregnancy if it happens.

- Obviously, any decision needs to take account of the specific circumstances of the family in question. However, it is very important to recognise the negative implications of forcing a medical intervention on a girl in her teens that she does not want and that is not needed for clinical purposes. It may well damage her relationship with her parents, undermine her sense of self-esteem and self-worth if her parents fail to trust her or support her to make safe choices. In this situation, it may be in the best interests of the girl to spend time exploring her choices, the risks she might be facing, the implications of all those choices, and then encouraging her to think about what action she feels would be best for her.

Activity 2.3: Assessing best interests and competing interests in practice

- We have completed more of the table below.

| Rights and best interests of a child | Interests of other children | Interests of parents/family | Interests of wider society | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rights in the UN Convention and the African Charter | Children have a right to be protected from all forms of violence Children have a right to live with their parents, unless it is bad for them | Families have a responsibility to direct and guide their children | Governments should ensure children are protected from violence and abuse | |

| Views of the child | Achen does not want to tell her mother as she is worried about the consequences in the short term | Achen has not considered the interests of other children | Achen is worried about the impact on her family | Achen may be worried about the way others in the community will treat her and her parents |

| The child’s other needs | Achen is suffering from headaches; there may be physical and emotional harm which affect her; her education may be affected | Achen may provide support in the home which includes looking after younger children | Achen’s family may rely on her to carry out work | Achen may perform other roles in the community which are affecte d |

| The child’s immediate and long term interests | Removing Achen from her family will prevent further sexual abuse; if this happens, Achen may also be restricted in how often she can see her mother in future | If action is not taken to prevent further sexual abuse in this case, it may mean that action is not taken for other children in the future | Achen’s mother will need to experience distress in the short-term if she is told; in the long-term she can take action to protect her daughter and other children | Taking visible action in one case may deter others from committing offences |

- Achen has a right to be protected from violence and abuse. It is not clear from the information given as to how long the abuse has been continuing for, but it may be over a long period of time. Abuse is likely to continue unless some action is taken. Achen is very worried about the consequences, including the potential for embarrassment to her family and damaging the relationship between herself and her mother. Her fears may or may not be realised, but even if they are, the need to act to prevent further abuse is an overriding concern. It is in Achen’s immediate and long-term interests that action is taken to investigate and prevent further harm to her, and potentially to other children in the future. Action may include: questioning Achen to obtain further facts, reassuring her that she is not to blame and that she has done the right thing by telling you, reporting the information to a more senior member of staff, recording the information for monitoring purposes, and depending on your position and level of seniority, reporting the information to an external authority, who can investigate the claim.

3 Addressing violence against children

Focus question

How can you support children’s right to protection from violence?

Key words: emotional abuse, neglect, physical abuse, sexual abuse, violence

3.1 Introduction

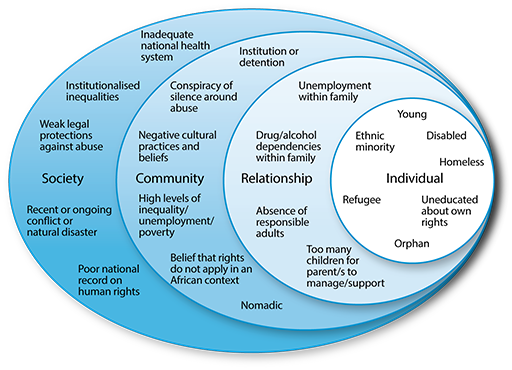

Many children face violence in their homes, at schools and in their communities. The impact of neglect, physical, sexual and emotional violence and abuse on children is significant. It can damage their health, well-being, growth and ultimately their development into adults able to create strong family and community units. It is important for health practitioners to have an understanding about the factors that are likely to place children at risk of violence, and to recognise key signs and indicators of abuse. In this session you will explore the various forms of violence that may be inflicted on children and consider the impact of such behaviour. You will also learn about the strategies that may be used to prevent and respond to violence in the communities where children live.

3.2 Learning outcomes

At the end of this study session, you will be able to:

- define and use correctly the key words and terms above

- explain the right for children to be safe from all forms of violence

- identify the risk factors for violence against children

- describe the effects of violence on children

- recognise the key symptoms of a child who is a victim of violence

- understand how to conduct an appropriate professional response.

3.3 The right to protection from violence

The legal right to protection

Violence against children happens regardless of where they live, and regardless of their race, class, religion or culture. It is never justifiable. You will know from your study of Module 2 that both national and international law and conventions recognise children’s right to protection from all forms of violence.