Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Monday, 9 March 2026, 10:51 AM

Module 4: Module 4 - Children’s rights in the wider environment: the role of the health worker

Introduction to Module 4

This is the fourth module in a course of five modules designed to provide a comprehensive introduction to children’s rights for health workers. While the modules can be studied separately, they are designed to build on each other in order.

Module 1: Childhood and children’s rights

Module 2: Children’s rights and the law

Module 3: Children’s rights in health practice

Module 4: Children’s rights in the wider environment: the role of the health worker

Module 5: Children’s rights: planning, monitoring and evaluation

Module 4 provides three study sessions for health care practitioners in relation to some of the broader issues in ensuring children’s rights in health care settings. Each of these sessions is designed to take approximately two hours to complete. The sessions provide you with an introduction to these topics and are supported by a range of different activities to help you develop your understanding and knowledge. The activities are usually followed by a discussion of the topic, but in some cases there will be answers at the end of the study session for you to compare with your own answer before continuing. We have provided you with space to write your notes after an activity, however if you wish, you can use a notebook.

- Study Session 1 builds on your knowledge of health and the right to health as a very broad issue. Health is not just about individual health and medical treatment but is influenced by a wide range of factors in society such as poverty, bad housing, and lack of access to clean water. By the end of the session you will have a better understanding of these challenging factors, their impact on health, and how they relate to the role of the health worker.

- Study Session 2 explains the important role of a person who listens to children and helps them express their views or argue for change. This role (called an advocate) and what they can do is discussed and explored. By the end of the session you will have an understanding of how health workers could and should be advocates for children’s rights.

- Study Session 3 builds on your learning about being an advocate and explains how whole communities can be mobilised to take action on children’s rights. The session will explore how to identify issues in your community that are having a harmful effect on children’s health and how to mobilise the community to address the problem. You will learn about practical techniques and strategies and the role that children themselves can play.

1 Understanding the social determinants of health in the context of children’s rights

Focus question

How do social determinants of health impact on children’s rights?

Key words: health disparities, health inequity, social determinants of health, social justice

1.1 Introduction

This session introduces you to the idea that health is not simply a medical issue based on biological factors and medical interventions. Health is also a result of how and where you live. For example, poverty, bad housing, stress, lack of access to clean water, and unemployment all contribute to how healthy you are. The social conditions in which people live have a dramatic impact on their health. These social conditions are known as the ‘social determinants of health’. Health is a product of the interaction between our biological makeup and the conditions in which we live and act.

This session will help you to understand what the social determinants of health are, and how they affect the health of children. It will also explore the way in which you, as a health worker, can support the right to the best possible health of children by taking action to address these social determinants.

1.2 Learning outcomes

When you have studied this session, you should be able to:

- define and use correctly all of the above key words

- explain the social determinants of health and their relationship to children’s rights

- identify the principles of social justice and health equity in respect to children’s rights

- understand the role of the health worker in addressing the social determinants of health in relation to children.

1.3 What are the social determinants of health?

What is your understanding of health?

When we talk about someone ‘who is in good health’, what do we mean? The answer can depend very much on the context. A 60-year-old man who is physically frail but mentally strong and alert may be described as in good health, whereas we would not describe a 20-year-old pregnant woman as being in ‘good health’ if she was physically frail yet mentally strong.

Health can be defined as: a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being, and not simply the absence of disease or illness.

If we asked people in a poor community for their definition of good health, how do you think that would differ to the response we would get asking the same question in a wealthy community?

The social determinants of health are the circumstances in which people are born, grow up, live, work and age:

- Social determinants of health are risk factors found in a person’s living and working conditions (such as the distribution of income, wealth, influence, status and power), that influence the risk for a disease, or vulnerability to disease or injury. They are not in the individual (such as behavioural risk factors or genetics).

- Social determinants of health include early childhood development, education, economic status, employment and work, housing environment, and effective prevention and treatment of health problems.

These circumstances are shaped by how money, power and resources are distributed at global, national and local levels. They can cause unfair and avoidable differences in health. These differences are known as health inequities between and within communities. For the majority of people, poor health arises from social and economic factors.

The World Health Organisation (WHO), a global body set up to promote the right to health, has published research to say that ‘this unequal distribution of health-damaging experiences is not in any sense a “natural” experience but is the result of a deadly combination of poor social policies, unfair economic arrangements [where the already well-off and healthy become even richer and the poor who are already more likely to be ill become even poorer], and bad politics.’

The WHO developed a Commission on Social Determinants of Health, which in 2008 published a report entitled ‘Closing the gap in a generation’. This report identified two broad areas of social determinants of health that needed to be addressed. The first area was daily living conditions, which included:

- healthy physical environments

- fair employment and decent work

- social protection across the lifespan, and

- access to health care.

The second major area was distribution of power, money and resources, including:

- equity in health programs

- public financing of action on the social determinants

- economic inequalities

- healthy working conditions, gender equity

- political empowerment

- a balance of power and prosperity of nations.

As a health worker, you need to understand how social determinants impact on the health and child rights issues in your community. In the activity below, you will take time to reflect and think of experiences that impact on children’s living conditions and thus their health in your community.

Activity 1.1: Your experience of the social determinants of health

Answer the following questions:

- Think about your own experience of growing up. Can you think of social determinants that have shaped your own health?

- Think about a specific situation in your community where you have observed poor living conditions for children. What are the poor living conditions that might impact on their health? Think about them under the following headings:

- physical environment

- employment and work opportunities (for parents/guardians)

- social protection (for example access to education, a legal system, etc.)

- access to health care.

- Who do you think is responsible for these conditions having developed?

Discussion

Your answers to these questions will be dependent on the circumstances that you are familiar with in your own community.

- Your answer to this will be personal.

- In a general sense, poor living conditions are likely to be found:

- In a physical environment that is challenging, probably with little or no access to clean water, good food, sanitation, hygiene and reliable transport.

- Where employment and work opportunities are restricted, and the available options are low status, poorly paid and potentially exploitative.

- Where education is unavailable or is of low quality/value, and where people are unaware of their legal rights and/or unable and unsupported to claim them.

- Where access to health care is unavailable or very limited, and/or of low quality/value, for example where a service is focused only on expensive treatment rather than low cost, widespread prevention of disease.

You may have a very clear picture of how these conditions have developed in your own community, perhaps as a result of conflict, natural disaster or long-term policy decisions made by the local or national governing bodies – maybe even some combination of all three. You may just feel that the situation has been like this for so long that it is very difficult or impossible to describe how it came about. What is unlikely is that the people who live in poor living conditions have created them for themselves. Individuals are rarely able to exert direct control over the social determinants of their own health.

Living in these circumstances is hard for any adult, and children raised in such communities are likely to have very low expectations of what life has to offer. They will have a limited understanding of human rights and no way of knowing what their own rights are or how to claim them.

Study note

For ease in reading the text, from hereon we will be referring to the UN Convention and the African Charter.

Activity 1.2: Relationship of social determinants to the right to health

In an earlier session in Module 2 you learned about the right to health. Here is a reminder of Article 24 on the UN Convention.

- States Parties recognise the right of the child to the enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of health and to facilities for the treatment of illness and rehabilitation of health. States Parties shall strive to ensure that no child is deprived of his or her right of access to such health care services.

- States Parties shall pursue full implementation of this right and, in particular, shall take appropriate measures:

- a.To diminish infant and child mortality.

- b.To ensure the provision of necessary medical assistance and health care to all children with emphasis on the development of primary health care.

- c.To combat disease and malnutrition, including within the framework of primary health care, through, inter alia, the application of readily available technology and through the provision of adequate nutritious foods and clean drinking water, taking into consideration the dangers and risks of environmental pollution.

- d.To ensure appropriate pre-natal and post-natal health care for mothers.

- e.To ensure that all segments of society, in particular parents and children, are informed, have access to education and are supported in the use of basic knowledge of child health and nutrition, the advantages of breastfeeding, hygiene and environmental sanitation and the prevention of accidents.

- f.To develop preventive health care, guidance for parents and family planning education and services.

How do you think the social determinants of health affect the rights of children in your community to the best possible health, as well as other rights?

Discussion

It will be clear to you that the social determinants in a child’s life will have a significant effect on their right to health. For example, if they are unable to access clean water or have a nutritious diet, they will not achieve the best possible health. They will be vulnerable to disease, blindness and stunting. Social determinants such as discrimination against girls, can lead to situations where they have less priority for food within the family, or may be less likely to have access to health care. This too will compromise their right to health. These social determinants may also lead to children not being able to realise their right to education or to optimum development. Poverty and lack of employment can lead to children being required to participate in work from a very young age. Girls may be forced into early marriage and other forms of sexual exploitation.

1.4 Understanding social justice and health inequities

A socially just society is one that is based on principles of equality and fairness for all. An understanding and recognition of human rights is particularly important. The four principles of social justice are: equity, access, participation and rights.

Social justice means that the rights of all people in the community – particularly the groups that are marginalised and disadvantaged – are treated in a fair and equitable manner. Public policies should ensure that all people have equal access to health care services. For example:

- Someone with a low income should receive equity in the same quality health services that a person with a higher income receives.

- Someone living in a geographically isolated community should have the same access to clean water and sanitation as a person living in an urban area.

- Information designed to educate the community must be provided in languages that the community can understand rather than the preferred language of the governing class, enabling them to participate in the learning.

- The right of a child to health is as important as the right of any adult.

Social justice is what faces you in the morning. It is waking up in a house with an adequate water supply, cooking facilities and sanitation. It is the ability to nourish your children and send them to a school where their education not only equips them for employment, but reinforces their knowledge and understanding of their cultural inheritance. It is the prospect of genuine employment and good health: a life of choices and opportunity, free from discrimination.

Source: Mick Dodson, Annual Report of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander, Social Justice Commissioner, Australian Museum, 1993.

In reality, as you will know from your own experience, many people do not experience social justice. There are huge differences in health between different groups in society. These differences affect groups who are marginalised because of poverty, race/ethnicity, gender, disability, or where they live, or some combination of these. People in these groups not only experience worse health but also tend to have less access to the things that support health. For example, healthy food, good housing, good education, safe neighbourhoods, freedom from gender and other forms of discrimination. As we discussed, these are called the social determinants.

These disparities or differences in health are described as health inequities when they are the result of the systematic and unjust distribution of these social determinants. Health equity is when everyone has the opportunity to reach the best possible health, and no one is prevented from being healthy just because of their social situation.

Activity 1.3: Role play on disclosing and identifying social determinants that deepen child health inequalities

This activity is an option for those students who are studying the module with a group and not just as an individual. If you are not studying with a group you can still think about how the exercise would play out. You may even be able to try it with some willing friends or colleagues.

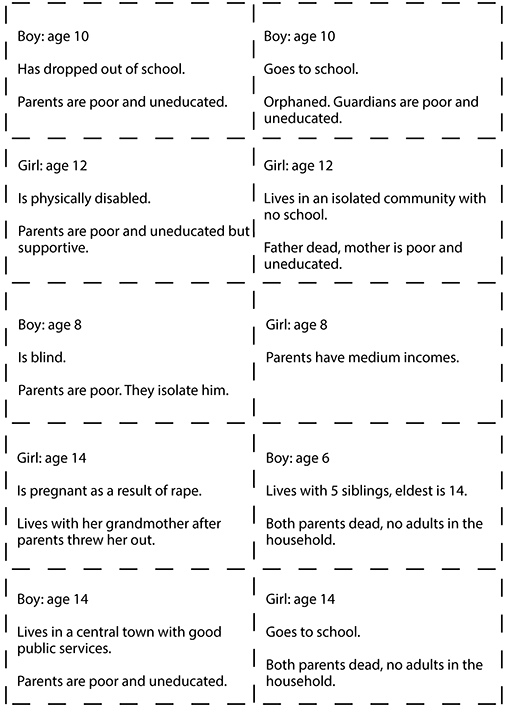

Please refer to Resource 1 on page 63, we have provided the activity template for you to print or draw and allow you to cut out each box. Each of the boxes represents a card. Hand out one card to each participant. Ten participants should be asked to study the information about the child on the card. Participants should not share which child they have been given and should line up in a row with backs against a wall or (imaginary) line on the floor.

Process for the exercise

The facilitator reads out the statements below. Considering the information on their card, each person should take a step forward each time they believe that the statement applies to the child they have chosen. If the statement does not apply then they should not move.

- My parents are mindful and support me to access health services whenever I am not feeling well.

- I get new clothes whenever I need them.

- I eat at least two meals a day and rarely feel very hungry.

- I sleep in a good house with clean and safe water and a toilet.

- I have access to and can read newspapers regularly bought by my parents/guardians.

- I have access and time to listen to the radio in our house.

- I can access/negotiate for youth-friendly health services from our community health centre.

- I go to school and my fee is paid promptly.

- I expect to finish my education and get a job.

- I feel I have positive choices about my own future.

- I am consulted on issues affecting young people in our community.

- My parents can pay for treatment in a private hospital, if necessary.

- I am prepared for and understand the changes that have happened/will happen to my body as I mature.

- I have access to plenty of information about health issues.

- My local health centre has staff who are medically trained, and it is less than 20 km away.

- I have a low risk of being sexually harassed or abused.

- My experience suggests to me that health workers are good people and are supportive when I go to a health centre.

At the end of the exercise, other participants might like to guess at the general conditions for each of those who were in the line up, based on their final position. When all the conditions are revealed, you can explore:

- What is the position of girls and boys from well-to-do backgrounds compared to those from deprived backgrounds?

- The wide distance between participants shows lots of real distance or inequalities in communities. What are they (social-economic, cultural, rural/urban, status, etc.)?

- Would the distance between people be different if more people/groups were communicating and sharing with each other? What would have happened to the ‘shape’ of the group at the end?

- What can be done to address the inequalities that are demonstrated in the exercise?

Discussion

At the end of the activity some people will be a long way from the starting line whilst others may not have moved from the start position. You can ask each participant to explain who their child was and why they are positioned where they are at the end of the game. This activity makes it apparent, very visibly, that children’s different life chances create inequalities between them and shows how some children get left behind. You can use this activity to explore the factors that lead to those inequalities and to think about which children lose out and how.

1.5 Taking action to address the social determinants of health

In every region of the world, the survival of a child past the age of five is shaped, to a large extent, by the wealth of their household, the region in which he or she lives, and the education of his or her parents. Children born in rural areas or urban slums, children born to mothers with lower levels of education, and children born to families with lower incomes do worse than others. For example, from a selection of countries where data is available in Africa, Asia and the Americas, a child born to the wealthiest 20 per cent of households is more than twice as likely to reach the age of five compared with children born to the poorest 20 per cent of households in urban areas. In Europe, it is the same: under-five mortality rates are at least 1.9 times higher among the poorest 20 per cent of households than among the richest 20 per cent.

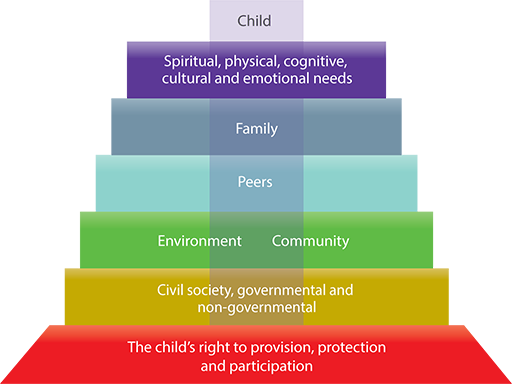

Statistics like those above illustrate the need for measures to address the inequalities that are affected by the social determinants of health. Every child counts and every stakeholder has a responsibility to do what he or she can to support their right to health. Action to address the social determinants that lead to health inequities for children needs to take place at all levels of society – from the family up to the national and even international level (Figure 1.1).

It is important as a health worker that you understand the very powerful effect of social conditions on a child’s health. It can affect how you treat and advise children and their families. In the following module, you will have the opportunity to learn about how to use advocacy and community mobilisation to try and change some of the underlying conditions that prevent children from realising their right to the best possible health. However, at the individual level you can:

- Use community health clinics and outreach to raise awareness of the socio-economic differences and how they impact on children’s health, for example, lack of knowledge about diet and nutrition, impact of poor housing, poverty, and lack of electricity on children's health.

- Ensure that there is no discrimination in the services you provide. The social or other circumstances of the child should not affect the treatment they receive. For example whatever the education status, religion, disability, or economic background of the child and their care givers.

- Take the social situation of each child into account when providing health advice and treatment.

Activity 1.4: Identifying action to address the social determinants

Think about the many children that you meet every day to provide health services at your facility:

- Which common illnesses or sicknesses do they present with?

- What do you know about their different home and living conditions?

- Can you think of examples when awareness of a child’s social situation has been crucial to successful treatment and/or intervention?

Discussion

Children will often arrive at your clinic or hospital with illnesses or conditions that are the result of the social determinants in the child’s life. Many children experience health inequities as a result of their backgrounds and their parents’ situation. It is important when treating these children that you are aware of their background and social and economic situation, as this could affect the advice or information you provide. For example, if a child is suffering from malnutrition, it is important to understand the reasons why before suggesting a solution. It may be that the mother needs help and guidance on good nutrition for her child. However, there is little point in providing such advice if the real problem is poverty rather than ignorance. In such circumstances, you might need to think about how to help the mother access the food she needs for her child. Obviously it is important that you treat children with the same respect, irrespective of their social backgrounds and status of their parents/care givers. However, sometimes the response to a situation may require interventions that go beyond the medical, where you see an opportunity to address some of the social determinants that are critical to their prevailing condition. For example, it is little use just providing a child with treatment to address illness caused by drinking polluted water if the child is going to return to a situation where she or he is forced into using the same water supply. You could use your role as a health professional to make sure the parents are aware of the risks, to encourage action to clean up the water supply or help the family find an alternative source of drinking water.

1.6 Summary

In Study Session 1, you have learned that:

- It is not just biological conditions and access to health care that affects children’s health. Social determinants of health are the economic and social conditions that influence individual and group differences in health status.

- Social conditions in which people live have a dramatic impact on their health. Circumstances such as poverty, poor schooling, food insecurity, exclusion, social discrimination, bad housing conditions, and deficient sanitation in early childhood and poor occupational skills in adulthood can all result in health inequalities between children.

- Social justice means that the rights of all people in the community are considered in a fair and equitable manner. The four principles of social justice – equity, access, participation and rights – must all be promoted at all levels of the community. Failure to address social justice leads to health inequities. And in turn, this leads to the failure to realise children’s rights to health as well as to other rights.

- Responsibility for addressing the social determinants of health that lead to health inequities lies at all levels of society – families, communities, local and national government and the international community.

- There is action you can take as a health worker to address health inequalities: for example, community health outreach to increase awareness of health inequities, ensuring non-discrimination in service provision, and taking account of social determinants when treating children.

1.7 Self-assessment questions

Question 1.1

What do you understand by the term ‘social determinants of health’? Give three examples.

Question 1.2

Give two examples of how social determinants of health impact on children’s right to health.

Question 1.3

What are the four principles of social justice and health equity in respect to children's rights?

Question 1.4

Provide an example of health inequities that you have in your community as a result of social determinants. What action could you take to address it?

2 Advocating for children’s rights

Focus question

What is the role of a health professional in advocating for children's rights?

Key words: advocacy, advocate, loud advocacy, quiet advocacy

2.1 Introduction

This session will introduce you to advocacy. It will explore how the work you do with individual children can be strengthened if you are able to advocate for changes that improve the situation of children. The session will provide you with an understanding of what advocacy is and why it is important for you as a health worker. It will also explore how you can get involved in advocating for children’s rights to bring about changes in their lives. This will include how you can support children themselves to be involved in advocacy for their own rights.

2.2 Learning outcomes

When you have studied this session, you should be able to:

- define and use correctly all the key words

- understand advocacy in the context of children rights

- identify different approaches to and strategies for effective advocacy for children’s rights

- demonstrate that children can be advocates for their own rights

- discuss the reasons why health workers should be involved in advocating for children's rights.

2.3 What is advocacy?

Advocacy is the act of pleading or arguing in favour of something, such as a cause, idea or policy. An advocate can also serve as a ‘change agent’ by influencing practice and public policies that benefit all people particularly those who are under-represented or have less power in society. In this session we are focusing on understanding advocacy and the role it can play in enabling children to achieve their rights. Advocacy on children’s rights is a means to ‘speak up for children’. Basically, it involves a set of activities designed to influence the practices, attitudes and policies of others to achieve positive and lasting changes for children’s lives. It can be done by adults on behalf of children. But children themselves can also be empowered to advocate for their own rights.

There is no one subject that advocacy is suitable for: the principles of advocacy can be applied to the health care of an individual child the quality of health services, or issues like child labour and corporal punishment. Take, for example, a community where there are many girls being forced into early marriage. As a health worker, you are very aware of the damaging health implications for girls who are very young brides and mothers. You might decide that you want to take action to address the problem. This process of active engagement in tackling a problem involves advocacy.

Activity 2.1: Advocacy in health services

- Read the statements below and tick the ones that you believe to be true.

Hospitals may be scary places for children.

Children have a right to information about their own health.

Children may be upset if they don’t understand what is happening to them.

Children have a right to information about their own treatment.

Children will always feel safe around an adult who is a health worker.

- Now go back and consider the first statement. What role do you think advocacy could play in helping children feel less scared about being in hospital?

Compare your answers to those at the end of the study session.

2.4 Why advocate for child rights?

Children’s rights in the UN Convention and the African Charter have been ratified in Kenya, Tanzania, Uganda and Ethiopia and are reinforced by the national laws of those countries. However, children continue to experience violations of many of their rights – within the family, at the community level, and through policies and laws at the level of local and national government. There is, therefore, a role for advocacy at all these levels. By doing effective advocacy, you can bring about key changes in local practice but also sometimes at the higher levels of policy and legislation that will have a lasting impact on children’s lives. It is possible to apply a child rights approach to advocacy on any local or international issues that affect children, such as education, health, protection or livelihoods.

Children often lack powerful advocates. They cannot vote, and have little influence with policy makers. It is important, therefore, that those people who work with and for children, and those who understand their lives, take responsibility to advocate for changes to improve children's lives.

You may already have performed an advocacy role in your work but if not can you think of an example from your experience where you could have taken up an issue raised by a child to act as an advocate?

2.5 Who can be an advocate?

Anyone can play a key role in supporting children, their families and communities to claim their rights. Often those people who have most contact with children in the course of their ordinary practice are best placed to advocate on their behalf. Any advocacy work that is undertaken will depend on the circumstances and the resources available, but does not necessarily need to involve significant resources. It does not necessarily need to be a special ‘added on’ activity but can be built into your day-to-day work of practical support to children.

Health workers, whatever their role, are particularly well placed to advocate for children. You are in a strong position to identify unfair or unhealthy environments and practices that are harmful for children or that violate their rights. For example, if services that children need are not available, you can play an important role in highlighting the gaps. You can then make the case for why these services are important. You can be a natural and powerful advocate on behalf of children’s health. Consider the following reasons why you are uniquely suited for advocacy:

- You put a human face to the statistics. You care for children every day who are affected by the environments in which they live and work. When you tell your story, you can make people understand the issue of children’s health in a way that fact sheets or statistics alone cannot.

- You have credibility. By the nature of your role, education and training, people in your community respect and trust you. When you speak out on an issue, you bring credibility and relevance to that issue.

- You have influence. Because you instil trust in others and add credibility to your cause, your investment in the community can inspire others to do likewise. Moreover, your voice may be listened to when other voices are not.

- Your patients are depending on you. Children cannot vote. They need your help to tell their story. You have the power to not only advocate for children, but for their families. Through advocacy, you can help ensure that decision makers are not simply recognising children’s health and well-being as an important issue, but that they are actively working to improve their health and their lives.

- You have passion. Advocacy allows you to dig deeper into your interests and touches on why you originally became a health professional. Through advocacy, you can channel your passion for health and well-being into lasting change. Advocacy allows you to help improve the lives of children while at the same time strengthening the role of your profession within the community.

- You have well-suited skills. Health practitioners already have the skills of an advocate. The same skills you use every day to establish trust, develop relationships, provide solutions to your patients and clients can be applied in your community advocacy work.

- You are not alone. Through advocacy, you can join other health practitioners, school personnel, youth organisers, agricultural groups and others.

Activity 2.2: What makes a good advocate?

- Think of a time when someone else helped you to get across your views or argued on your behalf.

How did that feel and how did they do it?

- What do you think are the skills and characteristics of a good advocate in working with children? Try to identify at least five things.

If you are working in a group discuss which skills are most important to fill in the boxes in Figure 2.1.

Discussion

- Reflecting on personal experience can help us think about good and bad experiences we have had. This might be realising the importance of advocacy, when you wished someone had been able to speak up for you but no one did. If you have had a good experience, what was it that made it successful? What attitudes or skills did the person have who helped you? This should help you answer the second question.

- Although there is no ‘correct’ list of skills, some of the following can be valuable for effective advocacy:

- to be a good listener – so you really understand what the issue is

- to be a good communicator – as you would need to be able to work with children and young people of different ages, and also explain the issues to other people

- to value the opinions of children – you must accept that children have valid opinions and that their experience is important

- to be assertive or persistent – some people might not be prepared to listen to the views of others, particularly those of children

- to be creative – as there is usually not just one approach for every situation to address the issue of children

- to be patient – as it might take a while to achieve change.

This is not a comprehensive list: you may have identified many others. For example, it is difficult to fairly represent the views of children without putting our own interpretation on what they have said or feeling that we know what they should have said. Good advocates are also often passionate about achieving change for the better. It is a skilled role but as you can see some of these skills will be ones that you should have anyway, as a result of your work as a health practitioner, also basic attitudes and values are equally important.

Children themselves have ideas on ‘what makes a good advocate’

- take the time to listen

- remain neutral

- have a friendly, informal approach and not be too rigid about things

- be good at working with young people and give information in a way that suits them

- take time to get to know them and their needs

- do not speak down to them

- only share information with others when they agree that it’s OK

- do not jump to conclusions

- consult them on all things.

You can see that there is some overlap with our adult views but children also raise some issues that adults may not have in their list: for example their concerns about confidentiality – that passing on information they give to an advocate will not just be shared with everyone without their permission. You will be aware of this issue from Module 3.

2.6 Approaches to advocacy

There are lots of different approaches for effective advocacy. One way of grouping them together is to think of them as ‘quiet’ and ‘loud’ advocacy.

Quiet advocacy

Quiet advocacy involves intimate discussions and personal persuasion in bringing an issue to people’s attention. This usually happens on a one-on-one basis between an advocate and the target audience of the advocacy. This usually employs interpersonal techniques in raising people’s awareness. Quiet advocacy could also happen between and among small groups of people such as in schools, women’s group meetings, or in other community settings. Techniques like sketches and drama may be considered relevant to this form of advocacy. Lastly, quiet advocacy could involve a network of like-minded individuals and organisations involved in cooperative work. Types of quiet advocacy therefore include:

- Individual advocacy – this involves someone who may not necessarily be connected to an advocacy organisation but who engages in advocacy work.

- Self-advocacy – this involves people who are directly affected by a particular issue speaking out for themselves.

- Peer advocacy – this involves people who were engaged in a particular issue in the past (i.e. child domestic workers), received services from an advocacy group, and are now themselves involved in the advocacy work.

Loud advocacy

Loud advocacy aims to create more of a ‘fanfare’ and involves strategies and activities that are used to try and reach a wider audience than quiet advocacy. Loud advocacy may employ media and press campaigns, lobbying and political pressure, grassroots organising, and other similar tactics. These strategies aim to raise awareness about issues and can be cost-effective considering the number of people that are reached. Types of loud advocacy are listed below:

- Legal advocacy is a form of advocacy where lawyers or qualified advocates may engage in representing people in court or lobbying for changes in laws regarding a particular issue.

- People-centred advocacy is where the public are encouraged to participate in supporting a particular initiative. Such advocacy work is carried out in various ways including, but not limited to, public demonstrations, rallies, leafleting, canvassing, and protests to help bring important issues to the political arena.

- Media-advocacy gets people interested in an issue by using TV, newspapers, radio, the internet, etc. This is an important form of advocacy because media reaches a lot of people. Media advocacy does a lot to fuel public concern in a particular issue.

- Lobbying comes from the word ‘lobby’ which refers to an entrance area or meeting place. In the case of advocacy, it refers to conversations and meetings where people get access to and seek to persuade those in power. Lobbying involves direct communication with decision-makers and others who have influence over them. Lobbying is about educating and convincing them to support and advance your agenda. The primary targets of lobbying are the people with the power to influence a policy change on your issue.

- Alliances and coalitions are a form of advocacy where individuals, groups and individuals join together to form a stronger body promoting or advocating for a certain issue.

Activity 2.3 Case study

In the following case study can you identify examples of quiet and loud examples of advocacy undertaken by the workers?

Martha, Rahel and Aman are workers in a children’s organisation in a city suburb.

They are active in promoting children’s rights and issues in their community. Recently, the rising number of cases of physical violence against children in their community came to their attention. This inspired them to act. They started out on their own by identifying who these children were by speaking with and befriending the children and their family members when they went to school, the shop or church. Some of the children were referred to them by other children who had been victims of violence.

After they have gained their friendship and trust, Martha, Rahel and Aman started listening to these children’s stories and what they would like to happen, and they also spoke to them about their rights. In time, the workers raised the issue with community members during a community meeting. They brought the issue to their children’s organisation and argued for it to take on the issue of child physical violence as part of their flagship programs. Soon, the children’s organisation engaged in bigger activities such as distributing flyers about violence against children. They also encourage politicians in their community to pass local ordinances protecting abused and neglected children. They worked with children to present a drama about child violence during a community festival and began forming networks with other children’s organisations in neighbouring communities.

Compare your answers to those at the end of the study session.

2.7 Advocacy with children

As you know from your study of this curriculum it is a guiding principle of both the UN Convention and the African Charter that children have the right to be heard and have their views taken seriously. However, generally, it is adults who have the power to decide how things are run. In practice it can be difficult for children to express their views or have their voices heard. Sometimes what is required to make sure this happens is advocacy with them and not just for them. Health workers provide support to children who come into health centres, clinics and hospitals. Advocating for child rights in health involves making this idea part of everyday health care practice. Health workers who care for children must be able to listen to children, respect their right to be heard and help them express their views to others.

Children can be involved in advocacy that is led by adults on issues concerning children, or they can be empowered to be advocates themselves. Organisations that work on issues affecting children need to move from talking on behalf of children to giving children opportunities to speak and empowering them to speak for themselves and their peers. Girls and boys in many different situations around the world have organised themselves to take collective actions and to promote and support their rights. Children will still need help to achieve this but rather than speaking for children, an advocate can be a facilitator. For example they could encourage and support their efforts with information and explanations about the way systems or bureaucracies work or with finance and technical assistance, such as helping them to produce a poster. It is children and young people who are taking the lead.

An example of a campaign run by children and young people on sexual abuse

Example from a pilot project involving World Vision Zambia in monitoring and evaluating children’s participation

A 12-year-old boy was sexually abused by a 26-year-old woman. In this community, there had been a project to run an advocacy campaign by children and young people to raise awareness of the prevalence of sexual abuse and children’s rights to protection. Local men, women and children had been provided with knowledge on protective legislation; they learned that under the laws of Zambia, defilement was a serious crime punishable by imprisonment. Upon hearing of the incident of defilement involving the 12-year-old boy, the community was concerned, and mobilised themselves to take action. They involved the police, and the boy received psychosocial counselling and, in his best interests, was removed from the abusive environment and sent to live with his aunt in another town to enable him to recover. The alleged perpetrator had run away by the time the police got involved. Nonetheless a search for her was launched. This incident illustrates both that children can be effective advocates in raising awareness of the need for action within their local communities, and also the power of communities to protect children as a consequence of that advocacy. They were empowered with knowledge on protective legislation for children that they acquired through this project. Had the incident occurred in the previous years prior to the start of the programme, it is possible that perhaps the community’s attitude towards the incident could have been one of showing very little concern.

Some of the benefits of child-led advocacy are:

- Children have a unique voice – they talk about issues clearly and simply.

- They can cut through technical jargon. They just want things to change.

- Decision-makers do not usually come into contact with children so when they do, they often find it refreshing, and they take notice of what children say.

- It will bring ideas from children’s reality and adults will be able to see the problem and the solutions through the children’s eyes.

- Children and young people will have ownership of the solutions.

- The visibility of children promotes recognition that children can express their views and can be active citizens and have rights.

- Children will learn new skills, gain self-confidence, and begin to have a voice and exert influence.

2.8 Strategies for advocacy

Step one: Identify the problem

What is the problem you feel children are experiencing – early marriage, violence in the home, discrimination against girls or children with disabilities, failure to ensure birth registration, failure to design child-friendly health services? For effective advocacy you must know what it is the children themselves are saying – listen and take their views seriously.

Step two: Decide what you want to achieve

What would need to change to address the problem – changes in laws, policies, attitudes, more resources? It is important to be clear about the cause of the problem, so that you can target your advocacy as effectively as possible. For example, if the problem is excessive physical punishment of children in the home, you need to be aware of what the law currently says about physical punishment. If the law already protects children, then the problem lies in its implementation, and that is where you need to put your energies. It is always useful to provide a very concrete proposal of what you want to happen – not just to criticise the current situation.

Step three: Get the facts

You need to be sure about your facts before you undertake your advocacy. What is the scale of the problem? What is its impact? What evidence do you have of the problem? For example, if you wanted to advocate to make your clinic child-friendly, as you learned in Module 3, you could undertake consultations with children, and possibly their parents, to find out how they experience the clinic. If you find consistent evidence that children are frightened of nurses, or that they do not feel safe in the clinic, you can use this evidence to begin to advocate for changes.

Step four: Design your message

You need to be very clear about what you are asking for. It is helpful to keep your message as simple, clear and focused as possible. You need to think about how to get your concerns across to others, and to try and engage with their concerns. Use evidence wherever possible, as facts will carry more weight than anecdotal information.

Step five: Decide who you need to influence

It is very important to be clear about who you need to influence and what opportunities exist for influencing things. You need to understand how and where policy decisions are made. If you want to improve the delivery of health services, you may need to target the health administrators or doctors. If you are trying to influence community attitudes toward children, then your focus of attention will be, for example, community leaders, parents groups, or religious leaders. If you are trying to get the law changed, you need to target policy makers, government ministers, parliamentarians. Once you are clear about who you need to focus on, you can then design your advocacy strategy.

Step six: Build alliances

You will need partners and alliances to build as much support as you can get to help you make your case. You might be able to get the support of all the other health professionals you work with. There might be local or national NGOs who would be willing to be a part of it. The media at local or national level can be important in raising awareness on all issues. You may also want to involve children directly as part of the campaign. The more support you can get the stronger your advocacy. Not only does it provide you with more people to engage in the advocacy, but it demonstrates the breadth of support for the case you are arguing.

Step seven: Decide your strategy

You may need different strategies to reach out to different agencies or organisations. For example:

- To reach the media, you will need to write press releases, letters to the paper, find a story of local interest that they can publicise and emphasise the human interest side of the story.

- To reach politicians, policy makers and officials, you will need to write letters, get petitions signed by as many people as possible, ask to meet parliamentarians.

- To reach out to local communities, you will need to organise public meetings or meet local community leaders.

Step eight: Review progress

You should regularly take stock of what you have achieved. Are there tactics that are not working? Then review and revise them. You need to communicate consistently with all your partners and alliances to ensure they are all working together. Remember that change can take time – you often need to be patient and prepared to stay committed for the long term. You can learn more about having a plan and checking how it is progressing in Module 5.

Activity 2.4: In your practice

It comes to your attention that there is a rising number of cases of physical violence against children in your community.

- How would you undertake advocacy with children?

- What kinds of advocacy techniques could you use?

If you are working in a group try to come up with at least three ideas for each question.

Discussion

- It can be particularly difficult for children to talk about violence but in a group children may be able to talk about how they experience violence in the community and what they would like to change. You could help them discuss what action they would like to take or who they could try and influence. Then discuss how they might achieve this – asking to meet someone in the community, making a poster, etc.

- What strategy you use will depend on your role but you may have thought about starting with colleagues who you can share your concerns with, or managers within your own health setting. You may use this quiet form of advocacy to ensure the development of some child protection policies or that the existing ones are used properly. It may be that an individual case has not been dealt with properly and that a young person may need someone to highlight this. You may have thought that rising violence against children in the community may need a broader strategy perhaps liaising with other professionals, bringing it to the attention of the relevant authorities in the community or finding out how to raise public awareness.

In order to take the issue forward, it helps to do some research into how many cases of violence there actually are, and the children could help to collect this information. You might also want to find out from parents what they thought about the issue and whether they were also concerned. You would need to find out what the law currently does to protect children from violence and whether the problem is inadequate legislation or poor implementation of the laws that do exist. Once you have done your research, you can then decide what needs to change and where you need to focus your advocacy.

2.9 Determining priorities to advocate for change

There are many ways health practitioners can use their expertise and knowledge of what happens to children as a consequence of public policy. The issues of primary concern vary across localities within countries and from country to country, but there are invariably more issues than there are time and resources available to commit. When determining priorities for change, you might consider the following issues:

- The scale and degree of harm. How many children are affected and with what degree of severity? Does it address all children or a selected few? What about children who are marginalised or suffer discrimination? How is it influencing child development? Which rights are not being respected?

- The degree of urgency. Is it an issue that should be addressed urgently to keep a greater number of children from being affected?

- The potential for enlisting support from others. A campaign is more likely to be successful if you can attract others to support the cause. Who is already on board, and who needs to be educated and/or convinced?

- The public sensitivity expressed for the issue. If the issue has attracted media attention or public interest, you can capitalise on this heightened sensitivity to promote the case from a children’s rights perspective.

- The current political environment. You can take advantage of windows of opportunity. Examples would include:

- a.when a relevant bill is passing a legislative body that can be amended to introduce better protections for children or

- b.a general election wherein you can lobby political parties or candidates to take your concerns or issues seriously.

- Cultural and religious context. What are the cultural and religious views? Will you be able to get support from religious communities?

- The scope of what needs to be done. What needs to be done and what resources will it require? Is it simply making a phone call, or a large-scale campaign spanning across systems?

- The level of resistance. Who is disinterested or in opposition? Why? How can their perceptions be changed?

- The likelihood of success. It may be a better investment of time to focus on policy issues that are attainable in the short-term, as well as other more challenging long-term goals.

2.10 Summary

- Advocacy for children and their rights is about listening to their views and speaking out on their behalf.

- Advocacy can raise consciousness among decision-makers and the general public about an issue or a disadvantaged group, with a view to bringing about changes in policy and improvements in their situation.

- Advocacy can take different forms and use a range of different techniques.

- Children can be supported to be very effective advocates for their own rights.

- An advocacy strategy sets out the policies and actions that need to be changed, identifies who has the power to make those changes, and analyses how you can influence those decision-makers.

2.11 Self-assessment questions

Question 2.1

Give two reasons why advocacy is needed for children’s rights?

Question 2.2

Identify three factors that make advocacy strategies successful/effective?

Question 2.3

Identify three reasons why health professionals should get involved in advocacy on behalf of or with children?

Question 2.4

Why is it important to engage in advocacy with children?

2.12 Answers to activities

Activity 2.1: Advocacy in health services

The first four statements are true, but the last one is not. A child may have had a difficult previous encounter with a health worker, or they might just be overwhelmed by the unfamiliarity of a medical environment. It is up to the health worker to recognise that the child needs reassurance in order to feel safe and that part of that reassurance is in making sure that the child is kept informed, in a way that is appropriate to their age, about what is happening to them. Taking into account the rights of children is good practice, but advocacy takes things a stage further.

In responding to the first statement, you can respond to an individual child who is scared by trying to reassure them. That would be part of your day-to-day role in working with children. But advocacy involves a different approach – rather than dealing with each individual child, you would try and identify the source of the problem and do something to change it. This might involve the following steps:

- Look at the pattern of how children feel when they have to come to hospital. Do most children feel frightened? If so, what are they frightened of?

- Is it possible to document the problems they experience? For example, they have never been away from home before; everything feels strange and unfamiliar; they do not know what is going to happen to them; they have no one to ask for help or information.

- Once you have the information about the sources of children’s fear, you could then use this information to advocate with the hospital administrators and doctors to take action. For example, the hospital could prepare a short information leaflet for every child being admitted; every child could have a named nurse who has special responsibility for caring for him or her and who the child could always approach for information; you could show the child around the ward to let them know where to find the toilets, how to get help if they need it and what the daily routines are.

- You could then check whether these changes have begun to reduce children’s anxieties and make their experience of hospital less distressing.

You might recognise that issues, such as the one discussed above, are problems but feel that in some health facilities it would be impossible to address because of lack of time, staff or resources. However, investment of time in advocacy to improve children’s experiences of their health care can lead to fewer demands on health professionals’ time in the longer term. For example, it is easier to treat children who are relaxed and confident than those who are frightened, crying and anxious.

Activity 2.3: Case study

These workers used a mix of different methods to try and advocate for these children. Discussing the issue with the children individually or in a small group and then raising their concerns with the community are examples of quiet advocacy. The workers then moved on to trying to get more attention for the issue by using ‘loud’ techniques such as leafleting and lobbying.

Being part of a specialist organisation Martha, Rahel and Aman probably had much more time and resource available to them than many health workers will. But it will not be appropriate in all cases to try and use many different forms of advocacy. You will need to choose which is likely to be most effective or which you can realistically achieve. Return to the same example and think about how you might be able to respond.

3 Community mobilisation: practical strategies

Focus question

What are the practical strategies for effective community mobilisation in the promotion of child rights?

Key words: community, community dialogue, community mobilisation, participation

3.1 Introduction

This study session will help you understand community mobilisation. Community mobilisation is an important strategy that health workers can use to help ensure that children’s rights are realised. It builds on many of the approaches explored in the advocacy study session, but looks at how to involve the wider community to come together to create changes to improve children’s lives. The session will explore how to identify issues in your community that are having a harmful effect on children’s health and work to mobilise the community to address the problem. It will provide you with guidance on the steps involved in mobilising local communities, as well as on different approaches that can be taken to achieve change through community action.

3.2 Learning outcomes

When you have studied this session, you should be able to:

- define and use correctly all the key words

- define community mobilisation in the context of children's rights

- describe the techniques and strategies that are necessary for involving communities in child rights activities

- understand the benefits of involving children and community in community mobilisation

- demonstrate the role of health professionals in mobilising communities for children's rights.

3.3 The concept of community mobilisation

A community is usually defined as a group of people who live within a geographically defined area and who share a common language, culture or values (Figure 3.1). In short, it is an area or a village with families who are dependent on one another in their day-to-day lives and activities, and who all benefit from that inter-dependency. However, sometimes a group of people who do not live together but have something in common like a special interest or job role are also referred to as a community.

To mobilise is to get something or someone ‘on the move’. It follows then that community mobilisation is about organising and motivating the community to move them towards achieving a certain goal. Community mobilisation is defined as a process through which individuals, groups and families, as well as organisations, plan, carry out and evaluate activities on a participatory basis to achieve an agreed goal. This might be on their own initiative, or for a goal suggested or initiated by others – like a health worker.

What do you observe from Figure 3.1? Can one person manage moving this big item they are struggling with? How do you get people to come together to moving this ‘BIG’ item?

This illustrates the idea of community mobilisation. Just as the community might need to come together to achieve any big task, so this can be the case with children’s rights and health issues. In an earlier session you looked at advocacy and explored how sometimes bigger (‘louder’) strategies are needed when supporting individuals. Sometimes to achieve a big change we need to find ways of motivating a whole community to take action.

Through community involvement, local communities and professional people can identify health problems, pool their knowledge and experience, and develop ways and means of solving them (Figure 3.2). Your role is to help the community organise itself so that learning will take place and action follows. The health worker cannot achieve wider health goals without involving the community. For example, a health worker might be facing regular cases of children with illnesses arising from drinking contaminated water. While you can treat each child, the only long-term answer is to address the source of the problem and try and improve the water supply. However, you cannot achieve this goal on your own. Only by mobilising the community might you be able to build the momentum necessary to take action to improve the water supply. This can only be achieved by building on the community’s knowledge and beliefs, not by anyone dictating to them what they should do (Figure 3.3).

Community mobilisation is …

Working with the whole community – women and men, young people, and children

Seeking to encourage individuals and the community to embark on a process of change

Using strategies over time to build a critical mass of individuals supportive of child rights

Supporting people to face the fact that issues such as violence against children and rights issues are not something ‘out there’: it is something we all grapple with in our communities

Inspiring and creating activism among a cross-section of community members.

Community mobilisation is not …

Only raising awareness

Working with one sector, group or sex

A series of one-off activities

Pointing fingers, blaming or assigning fault

Top-down programme implementation by an NGO to a community

Completed within short time frames.

Activity 3.1 Mobilising for birth registration

Look at UN Convention and African Charter in the resources, read what it says about birth registration and then answer the following questions:

- Which article and section explains the right to birth registration?

- Why is achieving higher levels of birth registration considered so important?

- How could community mobilisation help achieve this?

Compare your answers to those at the end of the study session.

Activity 3.2: Mobilising in your community

Now think of two other issues related to children’s rights in health care in the community where you work.

- Why are they important?

- Why would it be beneficial to involve the wider community in each case?

Discussion

- There is a whole range of issues related to health and to children’s rights where mobilising the community could play an important role. You might, for example, want to improve access to confidential reproductive health services for young people, address the prevalence of early marriage, tackle the harmful effects of child labour, improve the access to health care for children with disabilities. Discuss your answers with a colleague and see if they agree or have different suggestions about what issues could be tackled in your community.

- Communities are a primary source of solutions and sustainability for the promotion and respect of children's rights. By making efforts to involve all stakeholders, including children, in communities to promote children rights, you can achieve the following benefits:

- Community involvement helps bring together contributions of a variety of resources, including financial and material that are supportive of children's rights.

- Community involvement will lead to a positive influence on the community's perception of children rights.

- It creates ownership and sustainability for children's rights efforts through shared decision making and communication.

- It helps raise children’s concerns to the centre of the community agenda.

- Community involvement helps bring together different groups of people and organisations to collectively advocate for specific policies, attitudes and practices in support of the health and well-being of children.

- It can influence policies and attitudes more effectively than can be achieved through isolated efforts by individual organisations and people in a given community.

- It generates empowerment in the community that fosters individual and collective responses for children's rights.

- Community involvement helps in building sustainable social support systems that are beneficial to disadvantaged families and children.

3.4 Knowing your community

Community mobilisation will be more effective if you are able to encourage participation by as many community members as possible. To achieve this you really need to know your community well.

Activity 3.3: Describing your community

Think about the community that you live or work in. Imagine a co-worker from another area is coming to join you. What do you want to say right at the beginning about your community? Use the chart below to provide some of this information to the co-worker. If you have not yet started to work as a qualified health worker think about the community in which you live.

Write the following information about your community below:

| Community information | |

|---|---|

| Name of your area / village: |

|

| Languages spoken: |

|

| Festivals celebrated: |

|

| Beliefs and values held: |

|

| Religion practiced: |

|

| Resources available: |

|

| The particular health problems in this community are: |

|

| The main health inequities are: |

|

| The people who are influential are: |

|

Discussion

Your answers will be individual to you and your community. You may need much more detail than just these questions, such as, who are the most significant people in the community who could help you find out more or who will need to be involved because of their influence. The point of this question is that the more you know about the community, the more likely you will be to design children-related projects that fit the individual needs of that community.

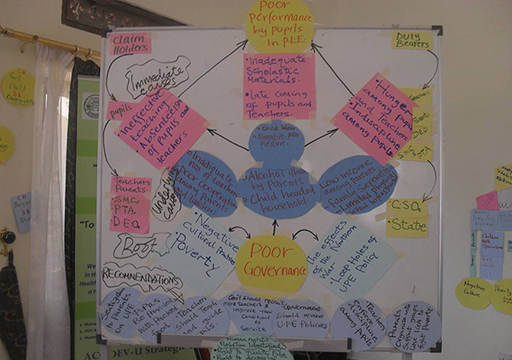

There are many tools and techniques for collecting information that will help you to know more about your community. You can find this out through direct observation, group interviews, sketching maps, listening to stories and proverbs, and holding workshops. To find out about the history of the community, you can create a ‘historic profile’. This allows you to become familiar with the history of the village. A village history will include the significance of its name, the people who founded it, and the major events that have marked it through time.

Now look back at the initial information you have written about your community. You may have identified a health problem or problems. But is the community aware of these? If you asked them, would they also identify the same problem? A community will only mobilise if they are convinced there is an important issue to mobilise around.

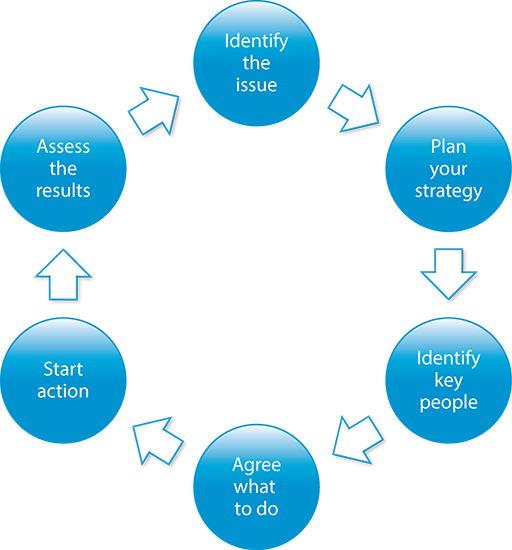

3.5 The action cycle of community mobilisation

Once you are familiar with the community, you can explore the health issues and child rights issues and why any specific problems are occurring. You should look for helpful or harmful health practices, beliefs, attitudes and knowledge within that community that are related to the health problem under consideration. Once the health issues are fully explored, you can set priorities, develop a more detailed plan of work and carry out the plan. During implementation of the programme, you should monitor and finally evaluate your activities (Module 5 has more information on monitoring and evaluation). Before starting a community mobilisation strategy, it can be helpful to think of the required activities in the form of a cycle (Figure 3.4). This is because as a health provider, you should start the mobilisation process by clearly setting the goal of the action and the steps to achieve it in your mind, then organise and plan the work with the community.

Here is an example of community mobilisation:

Step 1 Identify a significant health problem, for example, early marriage. You might already have ideas from your own experience as a health worker, or you might want to work with other members of the community, including children, to explore ideas.

Step 2 Plan and select a strategy to solve the problem. You will need to think about the causes of the problem and try to develop a plan to tackle those causes. You might do this by organising a workshop with key local people to explore what needs to change and how you might go about it.

Step 3 Identify key people and stakeholders. You need to involve as many people as possible from the community who are likely to be interested in the issue. But you also need to think about who are the influential people in the community who have the power to make change happen – for example, the local council chairperson, MP, cultural and religious leaders.

Step 4 Mobilise these key people and stakeholders for action. Engage them in discussions about possible activities and get agreement from everyone as to the commitments they are prepared to make.

Step 5 Implement activities to work towards a solution. You will need to follow up the commitments with action and have regular meetings to see what progress is being made.

Step 6 Assess the results of the activities carried out to solve the problem.

Step 7 Improve activities, based on the findings of the assessment. Following any community health activities, you should always get community members to participate in checking how well the activity went. Discuss the results with the community and in that way you can help them to learn. If they know why progress was achieved, or an action succeeded or failed, they will be able to make better efforts next time. If the programme seems successful, you should think about how you could scale up that method to a larger number of households. In this way, the action continues.

3.6 Issues to think about in undertaking community mobilisation

Overall, children’s health is going to be improved far more by the daily decisions and actions made by individuals and families in their own homes, rather than by health workers. So in order to make these daily decisions become healthy decisions, you should equip your community with appropriate skills and knowledge, and empower them through community participation. The greatest resources you have in your community are good relationships with individuals and groups; therefore, you should mobilise them to pool the resources available in the community (Figure 3.5).

Community participation is one of the key community mobilisation techniques. It is the involvement of people in activities of common interest to achieve common goals, working for a joint cause intended for the welfare or development of the people.

Local people have a great amount of experience and insight into what works for them, what does not work for them, and why. So they contribute to the success of any health intervention. Involving local people in planning can increase their commitment to the programme and it can help them to develop appropriate skills and knowledge to identify and solve their problems on their own. Involving local people helps to increase the resources available for the programme, promotes self-help and self-reliance, and improves trust and partnership between the community and health workers. It is also a way to bring about ‘social learning’ for both health workers and local people. Therefore, if you involve the local community in a programme that is developed for them, you will find they will gain from these benefits.

Benefits of community participation

- All social groups feel involved and participate in community matters.

- Solutions to problems are adapted to community capabilities acceptable to all community members.

- The community is empowered with an increased sense of ownership, self-responsibility, self-awareness and self-reliance.

- People are interested in having a well-sustained programme, building on existing local knowledge, resources and capacities.

- It generates community resources thus reducing the overall cost.

3.7 Engaging in community dialogue

Community dialogue is a process that draws community participants from as many parts of the community as possible to exchange information, views, ideas, share personal stories and experiences. This allows participants to develop solutions to community concerns. Its value as a process is that:

- It enables common values to be explored.

- It allows participants to express their own interests.

- It enables participants to grow in understanding and to decide to act together with common goals.

- It creates space for participants to question and re-evaluate their assumptions.

- It facilitates behaviour change.

- It can make unexpressed concerns visible.

- It encourages people to learn to work together to improve their situation.

Key characteristics of community dialogue

The key characteristics of a dialogue with the local community will involve the following:

- An emphasis on ensuring that the dialogue is targeted to individual behaviour as well as social change in the community.

- The community itself asks the questions and finds solutions, rather than looking to an external ‘expert’ to produce those solutions.

- A focus on resources that communities already have and building communities’ commitment to providing these resources.

- A move away from just giving messages and telling people how to behave and what to do, towards actively engaging the communities.

- A challenge to existing power relations, giving the weak and vulnerable a voice in any given community.

- Working through existing channels that are already well-organised and are using dialogue in various forms.

Tips to conducting a successful community dialogue

As a health professional the following tips can enable you to organise and conduct a successful community dialogue. Remember the nature of the community dialogue process can motivate people to work towards change. Effective dialogues do the following:

- Move towards solutions rather than continue to express or analyse the problem. An emphasis on personal responsibility moves the discussion away from finger-pointing or naming enemies and towards constructive common action.

- Reach beyond the usual boundaries. When fully developed, dialogues can involve the entire community, offering opportunities for new, unexpected partnerships. New partnerships can develop when participants listen carefully and respectfully to each other. A search for solutions focuses on the common good, as participants are encouraged to broaden their horizons and build relationships outside their comfort zones.