Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Monday, 24 November 2025, 12:31 PM

Module 5: Module 5 - Children's rights: planning, monitoring and evaluation

Introduction to Module 5

This is the fifth module in a course of five modules designed to provide health workers with a comprehensive introduction to children’s rights. While the modules can be studied separately, they are designed to build on each other in order.

Module 1: Childhood and children’s rights

Module 2: Children’s rights and the law

Module 3: Children’s rights in health practice

Module 4: Children’s rights in the wider environment: the role of the health worker

Module 5: Children’s rights: planning, monitoring and evaluation

Module 5 consists of two study sessions that introduce how to make plans to affect a change that will contribute to the achievement of children’s rights. It will also illustrate the tools you can use to check if the plan is effective. Each of these sessions is designed to take approximately two hours to complete. The sessions provide you with an introduction to these topics and are supported by a range of different activities to help you develop your understanding and knowledge. The activities are usually followed by a discussion of the topic, but in some cases there will be answers at the end of the study session for you to compare your own answer to before continuing. We have provided you with space to write your notes after an activity, however if you wish, you can use a notebook.

- Study Session 1 introduces the planning cycle and how you can go about making a properly structured action plan that can help to advance children’s rights. It explains some of the important terms that are used in relation to planning, and discusses the importance of involving children and others in developing plans. By the end of the session you will have a better understanding of how you, as a health worker, can make and contribute to action plans.

- Study Session 2 directly follows on from the first session as it explains the terms monitoring and evaluation. Both of these techniques are vital to know whether action planning has been successful. The session also explores the importance of involving children. By the end of the session you will understand the whole planning cycle and be able to plan a simple action plan to contribute to the achievement of children’s rights.

1 Action planning and implementation

Focus question

How can structured action planning help to advance children’s rights?

Key words: action planning, objective, task, resource, measure of success

1.1 Introduction

As a health worker, you have the potential to identify problems that violate children’s rights and the opportunity to work with others to develop solutions. When you decide to make an action plan, you are acting to change something that you consider to be a problem for children. You learned about your role in contributing to making changes in children’s lives in the previous module when you explored advocacy and community mobilisation.

In this study session, we will explore how to create and implement an action plan, and demonstrate how this can help to advance children’s rights. Action planning is a formal and structured approach to achieving change.

The session will also discuss the importance of involving children and others in developing plans so they are more likely to be relevant to children’s needs, more likely to be implemented, and more likely to deliver the results you want.

1.2 Learning outcomes

At the end of this study session, you will be able to:

- define and use correctly all of the key words above

- understand the importance of structured action planning

- understand the value of both children’s and other’s participation in developing an action plan

- create an action plan that links objectives, actions, measures of success and resources

- state the characteristics of a good action plan.

1.3 What is action planning?

When two or three people, or a larger group, meet together to discuss a problem or an issue they have identified, it is because they have decided that something needs to change. Similarly, an individual working alone may decide they want to see something change and can think about how this change should be made. As soon as we begin to think about what needs to change, we think about how the change can be made and we also think about who can make the change happen. When we think about these things, whether we know it or not, we are making plans. As humans, we do this informally all the time. When something is of particular importance, then we can think about the actions we want to take in a more structured way. The process of developing actions is called action planning.

An action plan is a list of key tasks that need to be undertaken to achieve a particular goal or bring about a particular change. Action plans differ from to-do lists because they focus on a single goal. An action plan states what needs to be done, by when and by whom.

Action planning is the process used to develop an action plan. It includes identifying the issue or problem clearly, developing specific and measurable actions, involving others and clarifying responsibilities.

In all action planning, the most important point to consider at the start of the process is the objective. What is the change you are trying to make? An objective can be defined as the specific result, goal or change you want to achieve. It is important to develop objectives that are:

- Specific: The objective should be well-defined and clearly understood by anyone with a basic knowledge of the work area.

- Measurable: It must be possible to know with certainty, if and when the goal has been achieved.

- Achievable: There must be agreement amongst all the stakeholders involved that the goal is within reach.

- Realistic: There needs to be sufficient knowledge, skills, resources and time to achieve the objective.

- Timely: There should be enough time to achieve the objective with the resources that are available and a clear end point.

These are known as SMART objective because in English the first letter of each bullet point spells the word 'SMART'.

Action plans can be developed for changes you want to see happen at any level from the immediate community to the international level. For example:

- a.Many children in your community suffer illness as a result of poor sanitation and water-borne diseases. Many parents lack awareness or knowledge of how to prevent these illnesses. You introduce a plan to provide children with information and practical guidance on how to make water safer. You then support them to take these messages out to the local community and participate in clean-up activities within local villages.

- b.At the East Africa Conference on Child Marriage, held in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, in June 2013, representatives from 20 organisations met to discuss the harmful effect of child marriage, which they described as ‘a neglected human rights violation’. Girls and young women affected by child marriage also attended the conference. The participants identified eight key actions that they believed would safeguard children’s rights and welfare, including enacting laws that establish a minimum age of 18 for marriage of both men and women, and enforcement of these laws. The participants recognise that their action plan is ambitious and that they cannot achieve the actions alone. Others, including governments, have the power to make some of these actions a reality.

We will return to the importance of involving others later in this study session, but for now you can note that the bigger the change you are aiming to bring about, the more people you will need to involve to make it happen.

Understanding action planning as part of a process

Action planning is part of a cycle of activity designed to create sustainable change in the realisation of children’s rights, as you can see in Figure 1.1. In this study session, we will explore two stages in the cycle: making plans and implementing them. Study Session 2 examines how to measure whether or not those plans have been effective.

The importance of action planning

When a project is relatively small and short-term, for example designing, producing, printing and distributing a leaflet, it may not be necessary or beneficial to develop an action plan. This is particularly the case where there are few people to be involved and what has to be done, and the steps to achieve it are clear. Tasks that are repeated often generally do not need an action plan. For medium-sized projects, such as organising a conference, an action plan can be very beneficial. For larger projects or programmes, such as opening a new health centre, an action plan is essential.

Action planning has a number of specific advantages over and above a list of things to do, or scheduling work using a calendar or diary:

- It provides an opportunity for reflection. Before beginning something, it is helpful to think about what has happened before, what actions have brought about success or partial success and what actions have not helped.

- It brings people together. Action planning can bring together individuals who are knowledgeable in the area of work (experts), individuals who are experiencing the problem and stand to benefit from the change (beneficiaries), and individuals who can contribute to the project (resources). In many cases, a person can have more than one of these roles.

- It clarifies the objective. It is often assumed that if a group of people come together to create an action plan, they will have the same objective, but that is usually not the case. A conference on forced child marriage, for example, may include people who are interested in influencing adults, people who are interested in empowering women and girls, people who want to work with young men, and people who want to create legal change. The emphasis of a project will change depending on the objective, and action planning provides the opportunity to clarify exactly what change is required.

- It builds consensus. Just as consensus on the objective can be achieved, consensus on priorities can also be achieved through the action planning process. Everyone involved can contribute their ideas, and gradually, through discussion, negotiation and compromise, the most important actions will emerge.

- It creates ownership and accountability. When people are involved in developing an action plan, they are more likely to contribute realistic suggestions that are often things they have some influence over. The involvement process creates a sense of individual and collective ownership for the action plan. This ownership allows for tasks to be allocated to different people, creating accountability. Individuals who are assigned tasks know they are responsible for these and that they will need to report progress at agreed intervals.

- It clarifies timescales. Setting out all the tasks that need to be done to achieve a particular objective and making decisions about how much resource is available for each task, allows for a realistic assessment of how long the overall action plan will take. Every action in an action plan should have a clear completion date.

- It identifies measures of success. Measures of success are like stepping stones towards a larger objective. They provide a way of measuring progress towards that goal. For example, if an objective is to prevent early pregnancy, there may be many steps towards that goal, including providing contraception, educating children and tackling child abuse. Each of these steps can be measured to ensure it achieves its aim and contributes to the larger objective of preventing early pregnancy.

Tasks, resources and measures of success

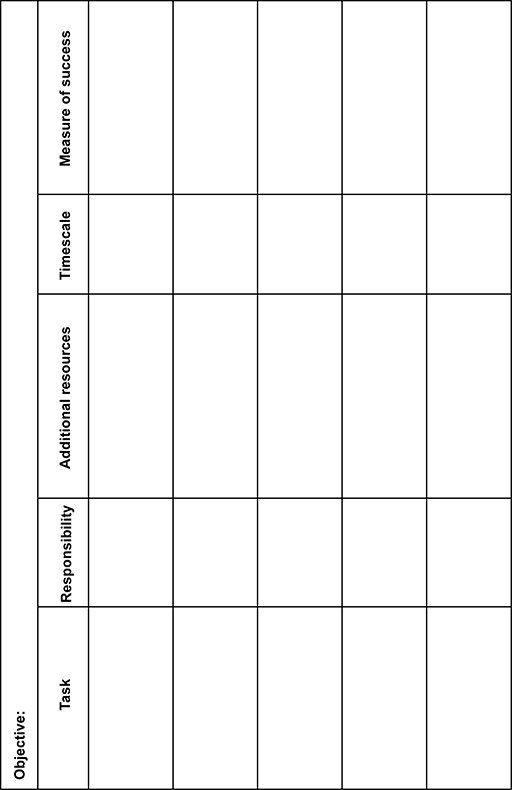

An action plan states what specific action needs to be taken (tasks), who will undertake each task and how (resources), and the immediate or short-term measurable result for each task (measures of success). Table 1.1 shows these different components in an action plan tackling the low level of birth registrations in a community.

| Objective: Build the evidence base to address low birth registration | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Task | Responsibility | Additional resources | Timescale | Measure of success |

| 1. Gather evidence on all birth registrations over the past 5 years | Head of clinic | Records from the local council | May 2014 | Data is collected and presented in an accessible format |

| 2. Analyse the data | Team of health workers | Staff at district council | August 2014 | Clear evidence of the patterns of birth registration is produced |

| 3. Undertake research into the barriers preventing mothers registering their babies | Team of health workers supervised by the head of clinic | Community development officers | October 2014 | Causes of non-registration are identified |

| 4. Produce a report with recommendations for action to remove the barriers | Head of clinic | Funds from district office | Dec 2014 | Report is available and ready to be used for the next stage of the process – to implement action to remove the barriers |

What do you notice about the structure and headings used in this action plan?

A number of things can be observed about the structure and headings used in this action plan:

- The objective is clearly stated at the start of the action plan.

- The activities that need to be completed are broken down into a number of separate tasks, four in this case.

- The tasks are listed in a logical order.

- The tasks all start with a word that conveys a sense of action, indicating that something will happen.

- Each task has been assigned to a person and the work has been divided between a number of different people. People are project resources.

- Each person has access to additional specific resources, that will support them in completing the task.

- Each task has a completion date.

- Each task has a specific measure of success, a way of assessing the immediate measurable result.

You can hopefully see that an action plan contains a very significant amount of important information. As described above, it might be helpful to a limited extent for a small project and it can be enormously valuable for medium and large projects.

We will now examine some of these components of an action plan in more detail.

Tasks

Tasks are the specific actions that, taken together, make up the action plan.

Resources

Quite simply, you cannot get anything done unless you have the resources to do it. Resources are the people, materials, money, or other assets that are available to contribute to the delivery of the action plan.

Usually the most important resources are the people who contribute to the delivery of the tasks in the action plan. Usually, it will be useful to identify one key person to take the lead responsibility for each task.

The other resources available to support the responsible person, are sometimes also listed against tasks in the action plan. These can be people, budget, buildings, materials and anything else that can be used to support the completion of the task. Where other resources are included the most significant resources should be listed in the action plan. For example, under the ‘Additional resources’ column in Table 1.1, it is assumed that the district council can provide additional support.

Measures of success

You need to be able to measure whether or not you have been successful in your action plan. You can measure progress by establishing what are called ‘indicators’. Indicators are facts that provide an objective measurement for assessing the state, level or condition of something, usually in an area where there is a desire to see change.

Just as each task in an action plan is a step that contributes to a bigger overall objective, each measure of success is a step towards the achievement of a larger success indicator.

We can illustrate this with another example:

A government official at the Ministry of Health in Kenya wants to improve the situation for vulnerable and marginalised people, including children, so that access to health services for mothers and young children is achieved universally across the country. There are differences in outcomes based on geography, social status and gender. She knows that there are a number of tasks to do, including gathering evidence, communicating this clearly, building support, lobbying other parts of government, making decisions about allocation of resources, involving vulnerable people in the process, and getting consent on the most important changes to be made. The first major task is to gather evidence and for this action, the indicator chosen is that the research will be up-to-date, informed by vulnerable and marginalised people’s experience, and written to a high quality. If this measure of success is achieved, it will make a significant contribution to the achievement of the larger success indicator for the entire project, which could be, for example, an increase of 15% access to health services for mothers and young children by a specified date.

1.4 Creating an action plan

Now the different components of an action plan have been introduced, it is your turn to create an action plan for a specific change you would like to see.

Activity 1.1: Creating an action plan for a change that you would like to see

If you studied other modules on this course, you will have learned about many different rights that children have. You will also know from your experience and local knowledge about difficulties that children might have in realising their rights, including securing their right to health.

Based on your knowledge and experience of this subject to date, can you think of a change you would like to see happen involving children’s health and/or their rights in your region or your community? What specifically would you like to see change? What would need to happen to make a difference to realising or advancing children’s rights? This should be something that you can influence, even if it means you need to involve other people. For this activity, think about a relatively small to medium-sized change you would like to see, for example a project to inform children about their rights, or a project to educate parents, or a project to make your practice more child-friendly. You could undertake this activity in your workplace and involve co-workers if you can.

The first step in creating your action plan is to define your objective clearly. When you have thought about a change you would like to see, write this in the form of an objective in the table below. Remember that objectives should be: specific, measurable, achievable, realistic and timely. You can check back on the definition of an effective objective described earlier if you are not sure.

The second step is to think about the tasks that will be needed to help you achieve your objective. Try to identify at least four tasks. Write the tasks in the task column, in a way that describes the act of doing something.

Next, think about who will lead each task. It might be you for all the tasks, or you might be able to ask others to take a lead. Do you need to consult them first? Write the name of one person under the 'Responsibility' column for each task.

Are there specific resources you and other responsible people can call on? Write these in the next column.

Now think about the timescales. It is sometimes helpful to think about the end date first. When would you like to have completed the plan by? Think about how long each task will take. Be realistic about this, bearing in mind the people and other resources available, conflicting tasks for other objectives, and whether any tasks can be carried out at the same time.

Finally, what will be your measures of success for each task? This is often the most challenging part of the action plan. Be as specific as you can here and try to describe measures in a way that contribute to your overall objective. If you are having difficulty identifying a suitable measure of success, then this is sometimes an indication that you have not defined your task clearly enough. Go back to the task and try to be more specific about the action that will be taken.

Once you have completed the action plan, spend some time reading and reviewing it. Read each action carefully, thinking about where improvements can be made to the plan.

Discussion

Did you find this activity difficult to do?

If you developed the action plan on your own, you may have found it more challenging, as you only have your own experiences and views to draw on. You might not have all the information you need and you have no way of checking with others whether the plan is achievable or realistic.

It is not unusual for one person to begin the process of drafting an action plan, but it is nearly always necessary to involve others before finalising it. Involving others as early as possible in the process is one of the best ways of building support for your plan. We will return to this discussion in the next section.

Ten characteristics of a good action plan

There are different views on what a good action plan should look like. It can depend on the scale and complexity of the change to be achieved. However, the following characteristics are important in all action plans.

- There is a single, clearly defined, objective.

- The timescales are realistic.

- The plan is informed by the past, but focused on the future.

- The plan takes into account external factors and constraints.

- The tasks in the plan all contribute to the same objective.

- The plan does not include anything unnecessary for the achievement of the objective.

- The plan is sufficiently detailed for its purpose.

- Responsibility for who does what is completely clear.

- The measures in the plan are clearly aligned to success.

- The plan is revisited and updated at appropriate intervals.

Looking back at the action plan you created, apart from the final characteristic which involves updating the plan, how many of these characteristics does your plan meet?

1.5 Involving children and others

Involving children

Involving children in action planning can provide a valuable source of information about their needs and experiences. Children of all ages can be involved, providing the methods of involving them are age-appropriate. By listening to children’s views and taking them seriously, children are empowered and can contribute meaningfully to the action planning process. By enabling children to participate, you are helping them to realise many of their rights under the UN Convention and the African Charter. This includes the right of children to access information, to express themselves freely, to have their views taken into account and to be active participants in their communities. They are also being prepared to take on responsible roles as adult citizens.

Children can be involved at a number of different levels, depending on their evolving capacities. There are numerous techniques available to enable children’s participation. You can refer back to Module 4, Section 2.7: Advocacy with children, for suggestions on how to involve children. In addition, some helpful resources are listed in the Bibliography at the end of the module.

Here we will talk a little about some of the good practice and ethical issues you will need to consider if you are to involve children in action planning, or in monitoring and evaluation.

Ethical issues

If children and adults are involved in action planning together, there are several important issues to bear in mind.

- Remember that there is a power imbalance between adults and children. Adults may be prepared to support children’s views, but they may not do so if they disagree with them. It is important to create space for children to say what they think without being intimidated by adults.

- Consent should be obtained from parents or guardians but children should also give informed consent. They should be aware of the purpose of their involvement and what is expected of them. They should not be forced to participate.

- Children should know about the boundaries of confidentiality and when it may be necessary to inform others about information they disclose.

- Children’s involvement should be valued, either through payment or other appropriate reward or recognition.

Child protection issues

Children should always be protected from harm. In any work with children, child protection is vitally important. Sometimes, if they get involved in community activity and speak out on key issues of concern to them, it may lead to a negative response from other members of the community. It is important to be alert to these issues. Children need to be informed and advised about possible risks, and protected from engaging in activities where they might be placed in danger. Wherever possible, it is helpful to identify a key person to take responsibility for ensuring children’s safety. Children need to know who that is and how to contact them.

Diversity issues

Because children have diverse backgrounds, experiences and needs, one child or a small group of children are unlikely to be able to inform you fully. It is important when involving children in action planning, to involve children with different backgrounds and experiences as much as possible. This can be challenging, because of insufficient time, insufficient resources to pay or reward more children, and the capacities of particularly vulnerable children.

The following tips may help you in thinking about ways of reaching and involving children from different backgrounds:

- Think about all of the different children who could be affected or could benefit – girls, children with disabilities, children out of school, very young children.

- Think carefully about the method of questioning and involving children. Will any groups find it difficult to understand and to participate? What different methods might work better for different groups? For example, through games, role play, drawing?

- Children that are particularly vulnerable and those with scarce resources will be able to participate more easily if the activity takes place near their home, school or at a community group. Take the work to them rather than expect them to come to you.

- Use methods that allow less confident children to express their views, for example it may be helpful to separate boys and girls for some of the time, or to ask children to work together in smaller groups.

- Agree on ground rules so that children feel safe, and challenge inappropriate language or behaviour, such as sexist remarks.

Accessibility issues

When working with children and young people with disabilities, it is important to think carefully about their communication needs. Some children will not be able to communicate their views in what you might consider to be the conventional way.

The most important thing you can do when working with children with disabilities is to avoid making any assumptions about what they are capable of. You should ask them directly, or their parents or guardians or other adults that work closely with them, about how the child normally participates and communicates.

While you should ask about individual needs, there are a number of things you should always do when working with children. Working in these ways will help to improve accessibility for children generally:

- Use simple and culturally relevant phrases with common local usage, and words that translate easily to the local setting.

- Remember that language is more than just words – facial expressions and body language can say a great deal.

- When communicating in print and using visual aids, use legible fonts and font sizes.

- Speak clearly and slowly if necessary, checking that children understand before moving on.

- Face the children so they can see your lips and face while you speak, and keep the background noise to a minimum if possible.

Involving others

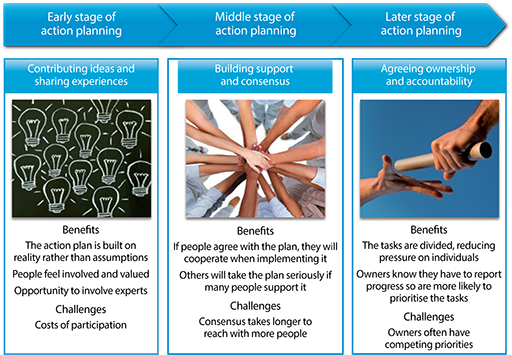

At several points in this study session, we have mentioned the importance of involving others in the action planning process. We talked about the importance of:

- bringing people together to contribute different ideas

- building support and consensus

- agreeing ownership and accountability.

These three elements are important throughout the process, but they each have greater importance at different stages of action planning. Listening to experiences and asking for ideas is more important at the beginning of the process. As the action planning process continues, building consensus and support for the plan that is emerging becomes more important. As the development of the action plan nears completion, agreeing ownership and accountability become the most important element. Figure 1.2 shows the relative importance of each element at different stages and also provides a summary of some of the benefits and challenges in managing each stage.

Activity 1.2: Good practice in involving others in action planning

Here are two scenarios about action planning.

For each scenario, can you identify:

- any good practice

- any things that could be improved

- your response as the health worker in each case.

Scenario 1

A health worker has been told by his manager that they need to write an action plan in response to a consultation that was held with children. The consultation was about children’s experiences of accessing and using health services. The health worker is given a summary of the consultation findings. The consultation took place two years ago and was mostly with children in the capital city. The health worker is based in a rural community. The health worker has been asked to produce a draft of the action plan for the manager to review in two weeks.

Scenario 2

A health worker based in a children’s ward of a hospital has attended a two-day training course on preventing the spread of communicable diseases. She has learned a lot about good practice in these two days and when she returns to her ward she notices there are many things not in place and improvements that could be made. She talks to her manager about this, but her manager is not supportive, saying they are too busy to take on any more work now. The health worker has worked at the hospital for a number of years and knows some of the senior staff quite well, so she decides to talk to the senior manager about whether action should be taken. The senior manager says there is already a communicable diseases policy and action plan in place for the entire hospital, which she will try to find. She is supportive, but is very busy and asks the health worker to wait until she can get back to her.

Compare your answers to those at the end of the study session.

Revisit you own action plan from Activity 1.1 and think about how you might ensure children and others are involved.

Remember that action planning is not a one-off exercise. Planning actions and implementing those actions are steps in a process of continuous improvement in your practice. Action planning and learning from experience will give you a structure to advance children’s rights and improve the health of the people you work with. This is over and above the immediate services and support that you provide every day.

1.6 Summary

In this study session you have learned what structured action planning is and how it can be used to advance children’s rights.

In particular, you have learned that:

- An action plan is a list of key tasks that need to be undertaken to achieve a particular goal or bring about a particular change.

- In all action planning, the most important point to consider at the start of the process is the objective. Objectives should be specific, measurable, achievable, realistic and timely.

- The action planning process is valuable because it provides an opportunity for reflection and brings people with shared purposes together. It also allows the objective to be clarified and consensus to be reached, and it creates ownership and accountability.

- Action plans have a number of components, including tasks, resources and measures of success.

- There are numerous techniques to enable children’s participation in action planning and in monitoring and evaluation. When children are involved, there are a number of good practice and ethical issues to be considered.

- It is important to involve others in action planning. This enables you to hear about different experiences, to gather ideas for the plan, to build consensus, and to divide the tasks so people know what they are responsible for.

1.7 Self-assessment questions

Question 1.1

Define what is meant by an action plan.

Question 1.2

Describe three reasons why action planning is important.

Question 1.3

List five key characteristics of a good action plan.

Question 1.4

Outline the issues to be considered when involving children in action planning.

1.8 Answers to activities

Activity 1.2: Good practice in involving others in action planning

There are no right and wrong answers here, but you may have identified some of the following things.

Scenario 1

It is good practice that children are being consulted about their experiences and that their views are being considered to inform an action plan. It is also good that the manager is involving other staff in the practice to help develop the action plan. However, there are many things that could be improved here. Firstly, the consultation took place a long time ago and services could have improved or deteriorated since that time. While many children in different locations will have similar needs, it is a big generalisation to suggest that the needs and experiences of children in a city will be the same as those in a rural area. Every location will have specific social, cultural and economic factors that affect children’s health. Finally, it looks as though the health worker has been given only a small amount of information about the consultation and has been asked to produce the plan in a short time period, making it difficult to consult and involve others.

What would you do? There are many different approaches you might take to improve the situation. You could ask to see the full consultation report. You could offer to consult with children in the community that you work with to check whether the findings are relevant in your area at this time. You could suggest forming a larger project team to discuss ideas. You might want to look at other sources of evidence available, and you might negotiate with your manager for a longer period of time to produce the action plan.

Scenario 2

This is a good example of how action planning can arise when people develop new knowledge and are able to identify problems and issues that they did not previously see. It is good practice that staff are being developed. It is also good practice that the health worker is trying to involve her line manager and other staff in the hospital. She has a clear idea of what can be improved, but recognises that leadership and support from others is necessary in this circumstance. The reactions from the manager and the senior manager are not too unusual in this case. People often see or agree with what needs to be done, but they have to balance this with other actions that are competing for their time. It is also not unusual for policies and plans to be developed with good intention but then for them to be forgotten about as new issues are given greater attention. Remember the ten characteristics of a good action plan that you learned about earlier? A good action plan needs to be revisited and updated at regular intervals.

What would you do? It is not possible in this case for you to develop an action plan, or involve others in developing an action plan, until you have permission and are allowed the time to do so. However, there are a number of things you might do to bring about changes to the practice in your ward. You can begin to make changes to what you do, leading by example. You can talk to some of your co-workers about what you have learned, encouraging them to attend training and to think about how they work. You might then be able to build support for your plan so that others raise the issue too. You could identify one or two small improvements that could be made immediately that require little time or cost and attempt to persuade your manager that these things could easily be done without interfering with other priorities. Lastly, you might be able to help your senior manager to find the policy and action plan she referred to. It may be displayed on a notice board, published on a website, or you might have received a copy as part of induction or training. You could follow up with her after a few weeks, perhaps telling her about the changes you are making to your practice and any positive results you have noticed.

2 Monitoring and evaluation in your practice

Focus question

How can monitoring and evaluation help to advance children’s rights?

Key words: evaluation, indicator, outcome, output, monitoring

2.1 Introduction

As a health worker who understands children’s rights, you are in a unique position to understand children’s experiences and to respond appropriately. You will do this every day at an individual level, however, you may not have a complete picture of many of the key issues and challenges, and your ability to influence change will be limited by this. Monitoring and evaluation are tools that can help you gain a more detailed picture. You can identify patterns, and understand which challenges are common and what kinds of actions are effective. This follows on from your work in Study Session 1 on planning as once you have implemented a plan you need to know if it is working or not, and the skills of monitoring and evaluating will help you do this.

In this study session you will learn what monitoring and evaluation are and how they can be used to advance children’s rights. You will appreciate the importance of involving children in monitoring and evaluation and you will develop skills to enhance monitoring and evaluation in your practice.

2.2 Learning outcomes

At the end of this study session, you will be able to:

- define and use correctly the key words above

- understand the importance of monitoring and evaluation to advancing child rights in your country

- understand the value of children’s participation in monitoring and evaluation

- use monitoring and evaluation tools in your practice as a health professional.

2.3 What is monitoring?

Monitoring involves the collection of information for a specific purpose. A simple example of monitoring in daily practice is keeping a record of the sex of the children that come to a medical facility and the medical problems that they bring. This type of monitoring information can help to determine accurately whether boys and girls are equally likely to seek medical assistance, and if they have different health needs. It can also help to find out whether boys or girls are being discriminated against. That information can then be used to plan services and ensure the right training and facilities are in place.

Monitoring is a process involving observation of something at regular intervals, such as weekly, monthly or quarterly. It involves gathering information. It can be used to assess the quality of a process or service. It can also be used to measure progress towards a specific goal.

Effective monitoring can help us to:

- Gather useful information from the routine tasks and activities that we carry out each day.

- Measure changes in services and experiences of individuals over a period of time.

- Assess whether resources are being used effectively or as we planned.

Monitoring is a vital part of action planning. In Study Session 1, you became familiar with making action plans and implementing them: the first two stages in the cycle shown in Figure 1.2. However, once you have put your plan into action, how do you know if it is working? If you had clear objectives and indicators for your plan it is through monitoring that you can see if they were achieved. So monitoring is a stage in a continuous process of improvement. Figure 2.1 is a reminder of the stages of this process.

Making decisions about monitoring

When introducing the monitoring of a plan to enhance child rights, it is important to consider the purpose of the monitoring and how the information will be collected and used.

The following questions are helpful to consider:

- What is the purpose of the information? Is it to support planning of services, to identify gaps in services, to help make decisions, or to help evaluate the impact of a project or take-up of a new service?

- What types of information will be needed? Examples may include, records of people seeking consultation, being tested or treated, or being referred elsewhere. It may involve recording characteristics of those individuals, such as their age, gender and whether or not they have a disability.

- How can the information be collected with the least possible effort? Monitoring is not an end in itself. The information collected will help to improve services, but too much time spent processing information will reduce the time available to provide services.

- Who will collect the information? Is it a single person, or will many people collect and record similar information? Is there a standard way of collecting information so it can be compiled more easily?

- Who will analyse the information? Information analysis may be fairly simple, such as manually adding up the number of children with a physical injury who attend a clinic. It may be more advanced, such as calculating the average age of those children with physical injuries that attend. It may be complex, such as identifying common issues from the feedback received from children.

Activity 2.1: Routine monitoring in your practice

Think about the types of information you might routinely gather in your work.

Write down in the first column below, two examples of information you already collect and record, or that you could collect and record, that links to the work you have done in the rest of the course about children’s rights. This could be information about individuals, such as their age or their medical history. It could be information about services, such as how often a person visits a health facility with the same problem or presenting complaint.

When you have at least two examples in the first column, try to answer the questions in the other three columns for each example. One row is completed as an example.

| 1. What information do you collect and record? | 2. Why do you collect this information? | 3. Who uses this information? | 4. What do they do with it? |

|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency that individual children attend a clinic | To identify children who are at risk | Other health workers Clinic manager | Take action to investigate and protect children from harm |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Discussion

- You could have included a wide range of examples in column 1, such as recording on each child’s record the date of their birth registration, their birth weight, or the dates they visit and the problem they present. Any information you collect is a form of monitoring. If you do not collect information about something, then you are not monitoring that activity. Check that your examples link to your learning on supporting children’s rights.

- Information should always be collected for a specific purpose. If you are recording the date that each child visits, then one of the purposes may be to assess how busy the service is at different times of the year. You might record the type and frequency of injuries to a child, so you can identify patterns that might indicate a child is experiencing neglect, abuse or violence.

- Apart from yourself, you may have noted other people use the information you collect. You may be asked to provide information to other people. If you record information on a computer system, you may be aware other people collect that information for a purpose. Do you know who they are? Are they based at your practice or elsewhere?

- Did you find this question harder to answer? You might know who else has access to the information you gather, but it might not be obvious why they need it or what they do with it. We will come back to this when we look at evaluation.

Tools to assist with monitoring: outputs and indicators

Outputs and indicators are important tools to assist the process of monitoring. In particular, they allow progress towards an objective to be monitored.

Outputs are generated as a result of particular efforts or activities. For example, the effort of researching, writing and editing, has resulted in the production of these educational materials on children’s rights for health workers. The material produced is the output of the effort that has been made. The output contributes to the objective of educating health workers about child rights. Whether or not it delivers that objective is dependent on many other factors, for example, the time that health workers have to study the materials. Other examples of outputs include the number of people that have been trained on a topic, the number of children that have been vaccinated against a particular disease.

Outputs are the specific type and amount of goods, services or other measurable results, which are produced by specific activities or effort. Outputs are planned, are usually clearly observable and measurable, and should contribute to a particular objective.

Indicators, or success indicators, as they are sometimes called, can help to measure progress towards a specific objective in a consistent and objective manner. Indicators are generally agreed in advance of activities that aim to bring about change, so that the effect of these changes can be measured. Returning to our example above of the production of educational materials on children’s rights for health workers, a success indicator in this case might be that 50% of health workers have access to the materials. In your work, an indicator that is more challenging would be that violence against children is shown to reduce over a period of time.

Indicators are facts that provide an objective measurement for assessing the state or level or condition of something, usually in an area where there is a desire to see change.

Activity 2.2: Monitoring specific issues in your practice

If you studied Module 3, Study Session 2, you may remember Achen, a 14-year-old girl who visited a doctor complaining of headaches. During the discussion, she broke down and said that her father was sexually abusing her. However, she did not want you to do anything or tell anyone because it would cause many problems. Her mother would not believe her and if action was taken against her father, it would destroy the family and her mother would blame her.

The case dealt with the difficult decisions you may have to make as a health worker in determining what action to take in the best interests of a child. Now we are going to think about this situation in relation to monitoring. Later we will use the same case to think about evaluation.

Take a few minutes to think about the following questions and write down a sentence or two in response to each. Share your ideas if you are working in a group.

- Why might you want to introduce monitoring for cases involving sexual abuse?

- What kind of information would be useful to collect?

- How might the information be used?

- Could monitoring of Achen’s case make a difference to other children?

- Can you identify at least one output and one indicator for this situation?

Compare your answers with the suggestions at the end of the session.

2.4 What is evaluation?

The purpose of evaluation is to determine if a desired objective has been achieved and the factors that led to that achievement. Evaluation provides an opportunity for reflection on what has worked well and what can be improved. It can also assist in identifying positive changes that can be made to services or practices to advance children’s rights. It can also avoid repeating activities that were ineffective. Look back at the planning cycle in Figure 2.1 to see where evaluation is in the process.

Evaluation is a structured assessment of the extent to which activities that have been undertaken have resulted in achieving a desired change. This may also include an assessment of the factors that led to success or failure of a particular project or activity.

The main focus for evaluation is on outcomes. You want to know whether the action you took led to a desired change. This can be illustrated by returning for the final time to our example of the production of these education materials on child rights for health workers. Evaluation is less concerned with outputs (e.g. the materials produced), or indicators (e.g. the proportion of health workers that have access to the materials), and much more concerned with outcomes. An important example of this would be whether health workers now have better knowledge of child rights and what difference this is making in their practice.

Outcomes are the measurable results of activities or projects. If planned outcomes are achieved, the activities or projects can be said to have been successful.

Planning for evaluation

In relation to projects or any activity that aims to bring about a change, it is important to plan the evaluation at the same time as planning the project itself, not during or afterwards. This will allow you to measure results as you implement changes.

Monitoring might be carried out on a continuous basis or, at regular intervals such as monthly or quarterly; evaluation generally tends to have a longer time period. Projects that run for several years might typically include a planned evaluation at annual intervals.

Responsibility for monitoring and evaluation

It is important to know who has responsibility for monitoring and evaluation, and at what level these activities are taking place, and how the evidence produced can be used to bring about positive changes to practice.

Activity 2.3: Knowing who has responsibility for monitoring and evaluation

Read the case study below and then answer the questions.

The East African Centre for the Empowerment of Women and Children (EACEWC) offers both education and health programmes in villages and communities. The Community Health Worker Programme consisted of a staff of ten health workers who went door-to-door each day to educate people about healthy practices, such as safe food handling and ways to prevent malaria. The first stage of the programme was evaluated as being successful because it reached 21,352 people in 6,745 homes in a single year. The initial success of the programme meant that it was integrated into the Kenyan government’s Community Health Plan, and the second stage involved training 50 volunteer Community Health Workers to expand the work and ensure it was less reliant on paid health workers.

- Who do you think was responsible for monitoring?

- Who was responsible for evaluation?

- Who was responsible for making decisions?

Compare your answers to those at the end of the study session.

The importance of evaluation

Look back at Figure 2.1 at the beginning of this study session. Evaluation is one part of a continuous process of improvement. As indicated earlier, improvements generally come about by learning from experience and learning can take place through effective monitoring and evaluation.

Effective evaluation can help us to:

- improve our understanding of the many factors that violate children’s rights, helping us to see patterns that we do not normally see in our work

- generate the evidence we need to make recommendations or seek additional resources to make improvements to services

- assess whether specific projects or activities are on track and are delivering the outcomes expected

Activity 2.4: Monitoring and evaluating projects

Earlier in this study session, we looked at a case involving Achen, a 14-year-old girl who was experiencing sexual abuse. You learned about the importance and benefits of setting up monitoring systems and reporting the results of monitoring. Where monitoring shows there is a problem that is more widespread, it can lead to the introduction of a project to tackle this problem.

We are now going to think about evaluation of a project that is being set up to tackle child abuse in the community where Achen lives. The project will be delivered by community health workers, and managed by a paid health worker who will report to a senior health worker. The project is funded by a non-government organisation (NGO).

The project has three aims:

- To increase reporting of all kinds of child abuse to community health workers.

- This aim will be achieved by creating and displaying posters in a health centre and by telling parents and teachers about the importance of reporting cases to the health worker.

- To increase awareness amongst children of their rights.

- The main activity will be to provide talks in the local schools and to provide leaflets for teachers and school assistants.

- To increase knowledge of child protection amongst parents and other adults.

- The main activity will be to provide a class for parents and teachers, covering different aspects of child protection.

Before the project starts, it is important to decide what information will be collected, why, how it will be used and where different responsibilities lie? All the activities above are the outputs of the project, and the aim of the evaluation is to assess the outcomes. In other words, do these activities lead to an increase in reporting of cases, which can eventually lead to action that reduces child abuse in the locality.

Many projects, like this one, will try to establish what is known as ‘baseline data’. This means there is a good knowledge of the current situation before the project starts, so that the changes brought about by the project can be measured. In this case, one type of baseline data is that we know the average number of child abuse cases that are currently reported to health workers in a 12-month period.

The table below is adapted from one used by the children’s charity, UNICEF, and is an example of how to monitor and evaluate procedures related to child protection. The framework will remind you of the different aspects of monitoring and evaluation that was introduced earlier. You can use it again when you come to think about your own practice in the final section.

Information for the first project aim has been completed and some information added for the second and third aim. Can you complete the table?

| Project aim | What do you need to know? | Indicator | Who will be responsible for monitoring? | How will the information be collected? | What will happen to the information? |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aim 1: Increase reporting of child abuse cases | If the number of cases reported has increased | Number of cases reported will increase by 10% in the first year | Community health workers and paid health worker | Community health workers keep records and are collated by paid health worker | Reported to senior health worker for evaluation of project and reporting to the NGO |

| Aim 2: Increase awareness amongst children | At least five schools participate in Year 1 and all distribute information to children |

|

|

| |

| Aim 3: Increase knowledge amongst parents | If parents are actively engaging in the project What parents think about the classes |

|

|

|

|

Compare your answers to those at the end of the study session.

2.5 Involving children in monitoring and evaluation

Child participation is increasingly being seen as good practice in community development programmes. As a result, children now participate in many programmes, not just when they start, but also in their planning and design. It is just as appropriate that children participate in the monitoring and evaluation of programmes that are intended to benefit them.

Involving children in monitoring and evaluation is important as children can provide a valuable source of information about their own needs and experiences. Parents and guardians may not be aware of all of their children’s individual circumstances, and children may not want to discuss some experiences with parents or other elders in their community. You will know from your study of Module 4, that children of all ages can be involved, providing the methods of involving them are age-appropriate.

As a health worker, you can involve children in ways that make them feel more respected. By listening to their views and taking them seriously, children are empowered and can reduce their dependence on others.

The UN Convention includes a number of articles that promotes children’s right to participation and to have their voices heard. You will have been introduced to these already if you studied earlier sessions.

Article 12 – Respect for the views of the child: When adults are making decisions that affect children, children have the right to say what they think should happen and have their opinions taken into account.

Article 13 – Freedom of expression: You have the right to find out things and share what you think with others, by talking, drawing, writing or in any other way unless it harms or offends other people.

Article 17 – Access to information: Children have the right to get information that is important to their health and well-being.

Levels of involvement

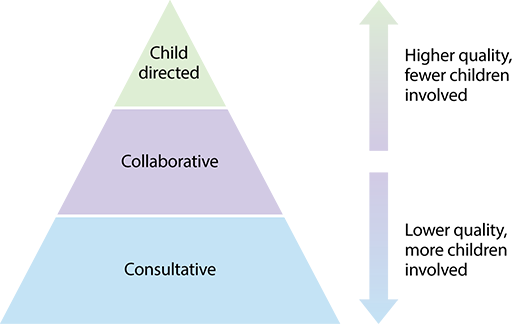

Children can be involved at a number of different levels, and their age, capacity and capabilities will have a bearing on what is feasible:

- Consultative involvement means collecting information from children as part of monitoring, for example, asking children their opinions about what they think is important and what might be monitored.

- Collaborative involvement means sharing decisions about what is monitored and what actions should be taken in response to particular issues.

- Child-directed involvement means that activities are initiated or led by children, and adults provide support to enable this to happen. An example of this would be, for example, supporting older children to obtain views from younger children through use of group drama.

Child-directed activities represent the higher quality of involvement, but because of the requirement for additional time and capability in these activities, it is usually only possible to involve fewer children. Figure 2.2 represents these different levels of involvement, with the highest point representing fewer children involved in higher quality engagement.

Top ten tips for involving children in monitoring and evaluation

- Involve children in topics and projects that will benefit them the most.

- Consider and manage the ‘costs’ to children, for example time, embarrassment, intrusion to privacy, anxiety.

- Ensure privacy and confidentiality so they have room to speak freely without fear of being reported.

- Think about selection and how you will be inclusive of the different groups, like boys and girls, disabled children, etc.

- Think about expenses, payments or other appropriate rewards. Children need to be provided compensation, food, toys, etc. during their participation processes including giving them time to play in between.

- Involve children in reviewing the plans and methods being used, not just the implementation.

- Make sure children and parents/carers are informed about the purpose.

- Make sure consent/assent is understood and freely given.

- Ensure children get information and findings in a format appropriate to their age and needs.

- Ensure there are no negative consequences or impacts on participants, they should be protected in all these processes from adverse outcomes of their participation.

Some of these tips and issues are discussed in more detail in Module 4. There are also some references at the end of this module.

Techniques to use with children in monitoring and evaluation

A wide variety of child-friendly techniques can be used to enable effective participation by children in monitoring and evaluation. These include:

- role-play, drama or use of songs, allowing improvisation to tell children’s stories

- photographs and video making

- children’s writings, essays, diaries, or recall and observations

- storyboards

- individual or collective drawing

- interviews.

There is not room in this study session to explore all of these techniques in detail. One example – body mapping – can be seen below.

Body mapping (before and after)

Body mapping can be used to explore changes in children’s views or experiences before and after their involvement in the programme. This tool is particularly useful for measuring outcomes when baseline information has been collected at the start of the programme. If baseline information was not collected, children can still be encouraged to reflect on changes arising from their participation ‘before and after’ the programme was implemented.

60–90 minutes

Resources

Sheets of A3 paper with an outline of a body drawn on them – one sheet for each child, one sheet of flipchart paper with an outline of a body drawn on it, different coloured pens and crayons, tape and Post-it notes.

What to do

Introduce the ‘before and after’ body mapping exercise that will enable girls and boys, individually and collectively, to explore changes in children’s lives or in children’s knowledge, behaviour or attitudes that are an outcome of their participation. These changes may be positive or negative, expected or unexpected.

Ask for a volunteer to lie down on the sheets so that the shape of their body may be drawn around. Draw around their body shape with chalk or (non-permanent!) pens.

Draw a vertical line down the middle of the body. Explain that this child is a girl or boy from their community. The left-hand side represents the child BEFORE their participation in the programme and the right-hand side represents the child AFTER their participation (now).

Explain that girls and boys will initially have the chance to think about and to illustrate changes arising from their participation in their individual body maps; after, they will have the chance to transfer their findings onto the big ‘body map’ to share key findings and experiences.

Give every child an A3 sheet of paper with the shape of a child’s body on it. The body is similarly divided by a vertical line down the middle. The left-hand side represents the child BEFORE their active participation in the programme and the right-hand side represents the child AFTER their participation (now).

Encourage each child to think about changes arising from their participation. Again, remind them that they can think about and record positive or negative changes. You can encourage them to think about the body parts to explore and to record before/after changes on Post-it notes. For example:

- The head: Are there any changes in their knowledge? Or what they think about/worry about/feel happy about? Are there any changes in the way adults think about children?

- The eyes: Are there any changes in the way they see themselves/their family/their community/their school? Are there any changes in the way adults see children?

- The ears: Are there any changes in how they are listened to? Are there any changes in how they listen to others? Or what they hear?

- The mouth: Are there any changes in the way they speak? The way they communicate with their peers, their parents, their teachers or others? Are there any changes in the way adults speak to them?

- The shoulders: Are there any changes in the responsibilities taken on by girls or boys?

- The heart: Are there any changes in the way they feel about themselves? Are there any changes in their attitudes to others? Are there any changes in the way adults or other children feel about them? Or others’ attitudes to them?

- The stomach: Are there any changes in their stomach? In what they eat?

- The hands and arms: Are there any changes in what activities they do? How they use their hands or arms? Are there any changes in the way adults treat them?

- The feet and legs: Are there any changes in where they go? What they do with their legs and feet?

- Think about and draw any other changes.

Give children time to draw or record these changes through words or images on Post-it notes on their body map.

After 20–25 minutes, encourage children to sit around the ‘big body map’ so they can share their individual findings and transfer them onto the ‘big body map’.

For each body part, encourage the children to share some of the changes they have recorded, if they feel safe and comfortable to share.

Encourage children to share expected and unexpected changes, positive and negative.

Ensure that all the children’s views are recorded in detail (but anonymously) by one of the evaluation team members.

2.6 Summary

In this study session you have learned what monitoring and evaluation are and how they can be used to advance children’s rights.

In particular, you have learned that:

- Monitoring and evaluation are stages within a continuous process of improvement.

- Monitoring involves the collection of information at regular intervals for a specific purpose. It can be used to assess the quality of a process or service, and it can be used to measure progress towards a specific goal.

- Outputs and indicators are important tools to assist the process of monitoring. In particular, they allow progress towards an objective to be monitored.

- Evaluation is a structured assessment of the extent to which activities that have been undertaken have resulted in achieving a desired change.

- Effective monitoring and evaluation can help us to measure changes in services and experiences of individuals over a period of time and assess whether resources are being used effectively or as we planned.

- Involving children in monitoring and evaluation is important. As a health worker, you can involve children in a variety of ways, and at different levels through a wide range of participation techniques.

2.7 Self-assessment questions

Question 2.1

In Study Session 1 you were asked to think about undertaking research into the barriers preventing mothers registering their babies and producing a plan for improving registration. How would you use monitoring to find out whether your plan had worked?

Question 2.2

What is evaluation?

Question 2.3

List three reasons why it is important to involve children in monitoring and evaluation.

2.8 Answers to activities

Activity 2.2: Monitoring specific issues in your practice

- As a health worker, you have a responsibility to identify risk factors experienced by the children you treat and to take appropriate action as early as possible. Regardless of what action you take in Achen’s best interests, you could also consider an action plan to tackle this issue. This requires that you are aware of risk factors and indicators of all forms of violence and of the local mechanisms of reporting. It is also important to know the extent of sexual abuse and whether children of particular ages, genders or living in particular locations are at risk. Monitoring will help to build up a more detailed picture of sexual abuse.

- Age, gender and locality are important factors. It will also be helpful to know the relationship with the person who has abused the child, at what age the abuse started, and the impact of the abuse on the child’s health and development. You may have identified other kinds of information that would be useful to collect so you can build up statistical information about child abuse over a period of time.

- If processes for reporting sexual abuse are in place, then the information collected may already be standard. If detailed reporting processes are not in place, then information about different child abuse cases could be brought together and analysed. As more information is gathered, it may become clearer where sexual abuse is more prevalent and which children are especially at risk.

- It is unlikely that a single child abuse case will lead to a programme of action to address child abuse in a community. However, analysis of monitoring information can create evidence, revealing the extent of child abuse and which children are especially at risk. Information about a single child may be ignored or explained away. Evidence generated from information about abuse of 50 children is much harder to ignore. It may lead to action that could help to prevent abuse of other children in the future.

- By planning to gather information, summarise it and produce a report about child abuse in a community, you will be creating an output. Your report is an output. If you know that reporting of child abuse is low in your community, you may want to encourage children and their parents or guardians to tell you. You could establish an indicator to increase the number of reports that are made to you.

Activity 2.3: Knowing who has responsibility for monitoring and evaluation

- In this example, the health workers had an important monitoring role because they needed to keep records of how many households they visited and how many people they spoke to. The volunteer Community Health Workers had a similar monitoring role in the second stage of the programme.

- Staff at the EACEWC were responsible for evaluation, collecting data together, summarising it and reporting progress to the Kenyan government.

- The government had responsibility for making decisions about the future of the programme. By including it in the Community Health Plan, they have indicated that they will support the work in the future, which may affect funding or other resources made available for the project.

It is not obvious from the case study, but in addition to measuring the number of people reached (outputs), information about the outcomes is important, for example whether the programme led to any reduction in health problems, such as food poisoning or malaria infection.

Activity 2.4: Monitoring and evaluating projects

| Project aim | What do you need to know? | Indicator | Who will be responsible for monitoring? | How will the information be collected? | What will happen to the information? |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aim 1: Increase reporting of child abuse cases | If the number of cases reported has increased | Number of cases reported will increase by 10% in the first year | Community health workers and paid health worker | Community health workers keep records and are collated by paid health worker | Reported to senior health worker for evaluation of project and reporting to the NGO |

| Aim 2: Increase awareness amongst children | If schools are actively engaging in the project | At least five schools participate in Year 1 and all distribute information to children | Paid health worker | Records of schools participating kept Records of leaflets distributed | Reported to senior health worker for evaluation of project and reporting to the NGO |

| Aim 3: Increase knowledge amongst parents | If parents are actively engaging in the project What parents think about the classes | At least 50 parents attend the class for adults Percentage of parents that give positive feedback | Senior health worker | Records of number of parents participating Records of feedback from parents | Reported to senior health worker for evaluation of project and reporting to the NGO |

Aim 1 is the primary aim of the project. The project recognises that child abuse cannot be tackled or reduced unless it is reported. If the project is successful, the number of cases reported will increase. This is not an indication that child abuse cases are increasing, but that the reporting of them is increasing. The indicator for this aim, an increase in reporting by 10%, can only be measured if ‘baseline data’ has been established. Baseline data is knowing what the rate is before any action is taken. If there was no baseline data, then the percentage increase could be replaced with the number of cases reported, which can be measured without baseline data. All the community health workers and the paid health worker are involved in recording information and reporting it.

Aim 2 is primarily a measure of output rather than outcome. It is concerned with getting schools involved in the project so that children can be educated about their rights and know how to report abuse. Getting five schools involved in the first year is an indicator of success, but it will also be important to know they are giving children the information the project wants them to receive.

Aim 3 is also a measure of output rather than outcome. It is concerned with educating parents and other adults about children’s rights so they know how to identify signs of child abuse, and can take action to inform children about their rights and protect them from harm. In addition to reaching at least 50 parents through a class, it is important that parents report positive feedback because they are more likely to take the advice seriously if they have felt the experience was worthwhile.

For all of the aims, the senior health worker has a key role in analysing the information received, evaluating the project as a whole, and reporting progress, outputs and outcomes to the NGO funder.

3 Answers to self-assessment questions

Study session 1

Question 1.1

An action plan is a list of key tasks that need to be undertaken in order to achieve a particular goal or bring about a particular change. An action plan states what needs to be done, by when, and by whom.

Question 1.2

Action planning offers a number of important benefits when seeking to bring about change in children’s lives:

- It provides an opportunity for reflection.

- It brings people together and enables you to utilize a broad range of skills and knowledge.

- It clarifies the objective.

- It builds consensus.

- It creates ownership and accountability.

- It clarifies timescales.

- It identifies measures of success.

Question 1.3

You could have identified any of the following characteristics of a good action plan:

- There is a single, clearly defined, objective.

- The timescales are realistic.

- The plan is informed by the past, but focused on the future.

- The plan takes into account external factors and constraints.

- The tasks in the plan are aligned and contributing to the same objective.

- The plan does not include anything unnecessary for the achievement of the objective.

- The plan is sufficiently detailed for its purpose.

- Responsibility is unambiguous.

- The measures in the plan are clearly aligned to success.

- The plan is revisited and updated at appropriate intervals.

Question 1.4

If you are going to involve children you need to make sure that you have considered the following:

- Ethical considerations – making sure that children give consent to being involved, respect for confidentiality and privacy, and that thought is given to making sure that children feel confident to express their views.

- Child protection considerations – you need to make sure that children are not exposed to risk by getting involved and that staff understand the importance of keeping children safe.

- Diversity considerations – think about which children are involved and which are excluded, make sure no child is discriminated against or made to feel uncomfortable because they are, for example, a girl, or are disabled or from a poor family.

- Accessibility considerations – if children with disabilities are involved you need to think about where they will meet and what are the physical barriers, such as steps or accessible toilets. You might also consider how to ensure you can communicate with children if they have learning or communication disabilities.

Study session 2

Question 2.1

Your plan should have had a clear measure of success in terms of increasing the number of birth registrations. Through monitoring you will have found out the numbers of registrations before you started and then carefully kept track of the number after your plan had been put in place. Monitoring will give you a clear measure of whether the numbers are going up. If you set a specific indicator, for example a 10% increase then monitoring will show you if this has been achieved.

Question 2.2

In the study session evaluation is defined as a structured assessment of the extent to which activities that have been undertaken have resulted in achieving a desired change. This may also include an assessment of the factors that led to success or failure of a particular project or activity.

Questions 2.3

There are lots of reasons why it is important to involve children in monitoring and evaluation. Your answer could have included:

- You will be promoting children’s rights to participation and having their voice heard.

- Children can feel more respected and empowered.

- Children can provide a valuable source of information about their own needs and experiences that no-one else knows.

Bibliography

Bonati, G. (2006) Monitoring and Evaluating with Children: A Short Guide, Plan Togo. Available at http://plan-international.org/files/Africa/WARO/publications/monitoring.pdf (Accessed 7 May 2014).