Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Thursday, 5 February 2026, 7:35 AM

TESS-India: Key resources

Planning lessons

Why planning and preparing are important

Good lessons have to be planned. Planning helps to make your lessons clear and well-timed, meaning that students can be active and interested. Effective planning also includes some in-built flexibility so that teachers can respond to what they find out about their students’ learning as they teach. Working on a plan for a series of lessons involves knowing the students and their prior learning, what it means to progress through the curriculum, and finding the best resources and activities to help students learn.

Planning is a continual process to help you prepare both individual lessons as well as series of lessons, each one building on the last. The stages of lesson planning are:

- being clear about what your students need in order to make progress

- deciding how you are going to teach in a way that students will understand and how to maintain flexibility to respond to what you find

- looking back on how well the lesson went and what your students have learnt in order to plan for the future.

Planning a series of lessons

When you are following a curriculum, the first part of planning is working out how best to break up subjects and topics in the curriculum into sections or chunks. You need to consider the time available as well as ways for students to make progress and build up skills and knowledge gradually. Your experience or discussions with colleagues may tell you that one topic will take up four lessons, but another topic will only take two. You may be aware that you will want to return to that learning in different ways and at different times in future lessons, when other topics are covered or the subject is extended.

In all lesson plans you will need to be clear about:

- what you want the students to learn

- how you will introduce that learning

- what students will have to do and why.

You will want to make learning active and interesting so that students feel comfortable and curious. Consider what the students will be asked to do across the series of lessons so that you build in variety and interest, but also flexibility. Plan how you can check your students’ understanding as they progress through the series of lessons. Be prepared to be flexible if some areas take longer or are grasped quickly.

Preparing individual lessons

After you have planned the series of lessons, each individual lesson will have to be planned based on the progress that students have made up to that point. You know what the students should have learnt or should be able to do at the end of the series of lessons, but you may have needed to re-cap something unexpected or move on more quickly. Therefore each individual lesson must be planned so that all your students make progress and feel successful and included.

Within the lesson plan you should make sure that there is enough time for each of the activities and that any resources are ready, such as those for practical work or active groupwork. As part of planning materials for large classes you may need to plan different questions and activities for different groups.

When you are teaching new topics, you may need to make time to practise and talk through the ideas with other teachers so that you are confident.

Think of preparing your lessons in three parts. These parts are discussed below.

1 The introduction

At the start of a lesson, explain to the students what they will learn and do, so that everyone knows what is expected of them. Get the students interested in what they are about to learn by allowing them to share what they know already.

2 The main part of the lesson

Outline the content based on what students already know. You may decide to use local resources, new information or active methods including groupwork or problem solving. Identify the resources to use and the way that you will make use of your classroom space. Using a variety of activities, resources, and timings is an important part of lesson planning. If you use various methods and activities, you will reach more students, because they will learn in different ways.

3 The end of the lesson to check on learning

Always allow time (either during or at the end of the lesson) to find out how much progress has been made. Checking does not always mean a test. Usually it will be quick and on the spot – such as planned questions or observing students presenting what they have learnt – but you must plan to be flexible and to make changes according to what you find out from the students’ responses.

A good way to end the lesson can be to return to the goals at the start and allowing time for the students to tell each other and you about their progress with that learning. Listening to the students will make sure you know what to plan for the next lesson.

Reviewing lessons

Look back over each lesson and keep a record of what you did, what your students learnt, what resources were used and how well it went so that you can make improvements or adjustments to your plans for subsequent lessons. For example, you may decide to:

- change or vary the activities

- prepare a range of open and closed questions

- have a follow-up session with students who need extra support.

Think about what you could have planned or done even better to help students learn.

Your lesson plans will inevitably change as you go through each lesson, because you cannot predict everything that will happen. Good planning will mean that you know what learning you want to happen and therefore you will be ready to respond flexibly to what you find out about your students’ actual learning.

Involving all

What does it mean to ‘involve all’?

The diversity in culture and in society is reflected in the classroom. Students have different languages, interests and abilities. Students come from different social and economic backgrounds. We cannot ignore these differences; indeed, we should celebrate them, as they can become a vehicle for learning more about each other and the world beyond our own experience. All students have the right to an education and the opportunity to learn regardless of their status, ability and background, and this is recognised in Indian law and the international rights of the child. In his first speech to the nation in 2014, Prime Minister Modi emphasised the importance of valuing all citizens in India regardless of their caste, gender or income. Schools and teachers have a very important role in this respect.

We all have prejudices and views about others that we may not have recognised or addressed. As a teacher, you carry the power to influence every student’s experience of education in a positive or negative way. Whether knowingly or not, your underlying prejudices and views will affect how equally your students learn. You can take steps to guard against unequal treatment of your students.

Three key principles to ensure you involve all in learning

- Noticing: Effective teachers are observant, perceptive and sensitive; they notice changes in their students. If you are observant, you will notice when a student does something well, when they need help and how they relate to others. You may also perceive changes in your students, which might reflect changes in their home circumstances or other issues. Involving all requires that you notice your students on a daily basis, paying particular attention to students who may feel marginalised or unable to participate.

- Focus on self-esteem: Good citizens are ones who are comfortable with who they are. They have self-esteem, know their own strengths and weaknesses, and have the ability to form positive relationships with other people, regardless of background. They respect themselves and they respect others. As a teacher, you can have a significant impact on a young person’s self-esteem; be aware of that power and use it to build the self-esteem of every student.

- Flexibility: If something is not working in your classroom for specific students, groups or individuals, be prepared to change your plans or stop an activity. Being flexible will enable you make adjustments so that you involve all students more effectively.

Approaches you can use all the time

- Modelling good behaviour: Be an example to your students by treating them all well, regardless of ethnic group, religion or gender. Treat all students with respect and make it clear through your teaching that you value all students equally. Talk to them all respectfully, take account of their opinions when appropriate and encourage them to take responsibility for the classroom by taking on tasks that will benefit everyone.

- High expectations: Ability is not fixed; all students can learn and progress if supported appropriately. If a student is finding it difficult to understand the work you are doing in class, then do not assume that they cannot ever understand. Your role as the teacher is to work out how best to help each student learn. If you have high expectations of everyone in your class, your students are more likely to assume that they will learn if they persevere. High expectations should also apply to behaviour. Make sure the expectations are clear and that students treat each other with respect.

- Build variety into your teaching: Students learn in different ways. Some students like to write; others prefer to draw mind maps or pictures to represent their ideas. Some students are good listeners; some learn best when they get the opportunity to talk about their ideas. You cannot suit all the students all the time, but you can build variety into your teaching and offer students a choice about some of the learning activities that they undertake.

- Relate the learning to everyday life: For some students, what you are asking them to learn appears to be irrelevant to their everyday lives. You can address this by making sure that whenever possible, you relate the learning to a context that is relevant to them and that you draw on examples from their own experience.

- Use of language: Think carefully about the language you use. Use positive language and praise, and do not ridicule students. Always comment on their behaviour and not on them. ‘You are annoying me today’ is very personal and can be better expressed as ‘I am finding your behaviour annoying today. Is there any reason you are finding it difficult to concentrate?’,which is much more helpful.

- Challenge stereotypes: Find and use resources that show girls in non-stereotypical roles or invite female role models to visit the school, such as scientists. Try to be aware of your own gender stereotyping; you may know that girls play sports and that boys are caring, but often we express this differently, mainly because that is the way we are used to talking in society.

- Create a safe, welcoming learning environment: All students need to feel safe and welcome at school. You are in a position to make your students feel welcome by encouraging mutually respectful and friendly behaviour from everyone. Think about how the school and classroom might appear and feel like to different students. Think about where they should be asked to sit and make sure that any students with visual or hearing impairments, or physical disabilities, sit where they can access the lesson. Check that those who are shy or easily distracted are where you can easily include them.

Specific teaching approaches

There are several specific approaches that will help you to involve all students. These are described in more detail in other key resources, but a brief introduction is given here:

- Questioning: If you invite students to put their hands up, the same people tend to answer. There are other ways to involve more students in thinking about the answers and responding to questions. You can direct questions to specific people. Tell the class you will decide who answers, then ask people at the back and sides of the room, rather than those sitting at the front. Give students ‘thinking time’ and invite contributions from specific people. Use pair or groupwork to build confidence so that you can involve everyone in whole-class discussions.

- Assessment: Develop a range of techniques for formative assessment that will help you to know each student well. You need to be creative to uncover hidden talents and shortfalls. Formative assessment will give you accurate information rather than assumptions that can easily be drawn from generalised views about certain students and their abilities. You will then be in a good position to respond to their individual needs.

- Groupwork and pair work: Think carefully about how to divide your class into groups or how to make up pairs, taking account of the goal to include all and encourage students to value each other. Ensure that all students have the opportunity to learn from each other and build their confidence in what they know. Some students will have the confidence to express their ideas and ask questions in a small group, but not in front of the whole class.

- Differentiation: Setting different tasks for different groups will help students start from where they are and move forward. Setting open-ended tasks will give all students the opportunity to succeed. Offering students a choice of task helps them to feel ownership of their work and to take responsibility for their own learning. Taking account of individual learning needs is difficult, especially in a large class, but by using a variety of tasks and activities it can be done.

Talk for learning

Why talk for learning is important

Talk is a part of human development that helps us to think, learn and make sense of the world. People use language as a tool for developing reasoning, knowledge and understanding. Therefore, encouraging students to talk as part of their learning experiences will mean that their educational progress is enhanced. Talking about the ideas being learnt means that:

- those ideas are explored

- reasoning is developed and organised

- as such, students learn more.

In a classroom there are different ways to use student talk, ranging from rote repetition to higher-order discussions.

Traditionally, teacher talk was dominant and was more valued than students’ talk or knowledge. However, using talk for learning involves planning lessons so that students can talk more and learn more in a way that makes connections with their prior experience. It is much more than a question and answer session between the teacher and their students, in that the students’ own language, ideas, reasoning and interests are given more time. Most of us want to talk to someone about a difficult issue or in order to find out something, and teachers can build on this instinct with well-planned activities.

Planning talk for learning activities in the classroom

Planning talking activities is not just for literacy and vocabulary lessons; it is also part of planning mathematics and science work and other topics. It can be planned into whole class, pair or groupwork, outdoor activities, role play-based activities, writing, reading, practical investigations, and creative work.

Even young students with limited literacy and numeracy skills can demonstrate higher-order thinking skills if the task is designed to build on their prior experience and is enjoyable. For example, students can make predictions about a story, an animal or a shape from photos, drawings or real objects. Students can list suggestions and possible solutions about problems to a puppet or character in a role play.

Plan the lesson around what you want the students to learn and think about, as well as what type of talk you want students to develop. Some types of talk are exploratory, for example: ‘What could happen next?’, ‘Have we seen this before?’, ‘What could this be?’ or ‘Why do you think that is?’ Other types of talk are more analytical, for example weighing up ideas, evidence or suggestions.

Try to make it interesting, enjoyable and possible for all students to participate in dialogue. Students need to be comfortable and feel safe in expressing views and exploring ideas without fear of ridicule or being made to feel they are getting it wrong.

Building on students’ talk

Talk for learning gives teachers opportunities to:

- listen to what students say

- appreciate and build on students’ ideas

- encourage the students to take it further.

Not all responses have to be written or formally assessed, because developing ideas through talk is a valuable part of learning. You should use their experiences and ideas as much as possible to make their learning feel relevant. The best student talk is exploratory, which means that the students explore and challenge one another’s ideas so that they can become confident about their responses. Groups talking together should be encouraged not to just accept an answer, whoever gives it. You can model challenging thinking in a whole class setting through your use of probing questions like ‘Why?’, ‘How did you decide that?’ or ‘Can you see any problems with that solution?’ You can walk around the classroom listening to groups of students and extending their thinking by asking such questions.

Your students will be encouraged if their talk, ideas and experiences are valued and appreciated. Praise your students for their behaviour when talking, listening carefully, questioning one another, and learning not to interrupt. Be aware of members of the class who are marginalised and think about how you can ensure that they are included. It may take some time to establish ways of working that allow all students to participate fully.

Encourage students to ask questions themselves

Develop a climate in your classroom where good challenging questions are asked and where students’ ideas are respected and praised. Students will not ask questions if they are afraid of how they will be received or if they think their ideas are not valued. Inviting students to ask the questions encourages them to show curiosity, asks them to think in a different way about their learning and helps you to understand their point of view.

You could plan some regular group or pair work, or perhaps a ‘student question time’ so that students can raise queries or ask for clarification. You could:

- entitle a section of your lesson ‘Hands up if you have a question’

- put a student in the hot-seat and encourage the other students to question that student as if they were a character, e.g. Pythagoras or Mirabai

- play a ‘Tell Me More’ game in pairs or small groups

- give students a question grid with who/what/where/when/why questions to practise basic enquiry

- give the students some data (such as the data available from the World Data Bank, e.g. the percentage of children in full-time education or exclusive breastfeeding rates for different countries), and ask them to think of questions you could ask about this data

- design a question wall listing the students’ questions of the week.

You may be pleasantly surprised at the level of interest and thinking that you see when students are freer to ask and answer questions that come from them. As students learn how to communicate more clearly and accurately, they not only increase their oral and written vocabulary, but they also develop new knowledge and skills.

Using pair work

In everyday situations people work alongside, speak and listen to others, and see what they do and how they do it. This is how people learn. As we talk to others, we discover new ideas and information. In classrooms, if everything is centred on the teacher, then most students do not get enough time to try out or demonstrate their learning or to ask questions. Some students may only give short answers and some may say nothing at all. In large classes, the situation is even worse, with only a small proportion of students saying anything at all.

Why use pair work?

Pair work is a natural way for students to talk and learn more. It gives them the chance to think and try out ideas and new language. It can provide a comfortable way for students to work through new skills and concepts, and works well in large classes.

Pair work is suitable for all ages and subjects. It is especially useful in multilingual, multi-grade classes, because pairs can be arranged to help each other. It works best when you plan specific tasks and establish routines to manage pairs to make sure that all of your students are included, learning and progressing. Once these routines are established, you will find that students quickly get used to working in pairs and enjoy learning this way.

Tasks for pair work

You can use a variety of pair work tasks depending on the intended outcome of the learning. The pair work task must be clear and appropriate so that working together helps learning more than working alone. By talking about their ideas, your students will automatically be thinking about and developing them further.

Pair work tasks could include:

- ‘Think–pair–share’: Students think about a problem or issue themselves and then work in pairs to work out possible answers before sharing their answers with other students. This could be used for spelling, working through calculations, putting things in categories or in order, giving different viewpoints, pretending to be characters from a story, and so on.

- Sharing information: Half the class are given information on one aspect of a topic; the other half are given information on a different aspect of the topic. They then work in pairs to share their information in order to solve a problem or come to a decision.

- Practising skills such as listening: One student could read a story and the other ask questions; one student could read a passage in English, while the other tries to write it down; one student could describe a picture or diagram while the other student tries to draw it based on the description.

- Following instructions: One student could read instructions for the other student to complete a task.

- Storytelling or role play: Students could work in pairs to create a story or a piece of dialogue in a language that they are learning.

Managing pairs to include all

Pair work is about involving all. Since students are different, pairs must be managed so that everyone knows what they have to do, what they are learning and what your expectations are. To establish pair work routines in your classroom, you should do the following:

- Manage the pairs that the students work in. Sometimes students will work in friendship pairs; sometimes they will not. Make sure they understand that you will decide the pairs to help them maximise their learning.

- To create more of a challenge, sometimes you could pair students of mixed ability and different languages together so that they can help each other; at other times you could pair students working at the same level.

- Keep records so that you know your students’ abilities and can pair them together accordingly.

- At the start, explain the benefits of pair work to the students, using examples from family and community contexts where people collaborate.

- Keep initial tasks brief and clear.

- Monitor the student pairs to make sure that they are working as you want.

- Give students roles or responsibilities in their pair, such as two characters from a story, or simple labels such as ‘1’ and ‘2’, or ‘As’ and ‘Bs’). Do this before they move to face each other so that they listen.

- Make sure that students can turn or move easily to sit to face each other.

During pair work, tell students how much time they have for each task and give regular time checks. Praise pairs who help each other and stay on task. Give pairs time to settle and find their own solutions – it can be tempting to get involved too quickly before students have had time to think and show what they can do. Most students enjoy the atmosphere of everyone talking and working. As you move around the class observing and listening, make notes of who is comfortable together, be alert to anyone who is not included, and note any common errors, good ideas or summary points.

At the end of the task you have a role in making connections between what the students have developed. You may select some pairs to show their work, or you may summarise this for them. Students like to feel a sense of achievement when working together. You don’t need to get every pair to report back – that would take too much time – but select students who you know from your observations will be able to make a positive contribution that will help others to learn. This might be an opportunity for students who are usually timid about contributing to build their confidence.

If you have given students a problem to solve, you could give a model answer and then ask them to discuss in pairs how to improve their answer. This will help them to think about their own learning and to learn from their mistakes.

If you are new to pair work, it is important to make notes on any changes you want to make to the task, timing or combinations of pairs. This is important because this is how you will learn and how you will improve your teaching. Organising successful pair work is linked to clear instructions and good time management, as well as succinct summarising – this all takes practice.

Using questioning to promote thinking

Teachers question their students all the time; questions mean that teachers can help their students to learn, and learn more. On average, a teacher spends one-third of their time questioning students in one study (Hastings, 2003). Of the questions posed, 60 per cent recalled facts and 20 per cent were procedural (Hattie, 2012), with most answers being either right or wrong. But does simply asking questions that are either right or wrong promote learning?

There are many different types of questions that students can be asked. The responses and outcomes that the teacher wants dictates the type of question that the teacher should utilise. Teachers generally ask students questions in order to:

- guide students toward understanding when a new topic or material is introduced

- push students to do a greater share of their thinking

- remediate an error

- stretch students

- check for understanding.

Questioning is generally used to find out what students know, so it is important in assessing their progress. Questions can also be used to inspire, extend students’ thinking skills and develop enquiring minds. They can be divided into two broad categories:

- Lower-order questions, which involve the recall of facts and knowledge previously taught, often involving closed questions (a yes or no answer).

- Higher-order questions, which require more thinking. They may ask the students to put together information previously learnt to form an answer or to support an argument in a logical manner. Higher-order questions are often more open-ended.

Open-ended questions encourage students to think beyond textbook-based, literal answers, thus eliciting a range of responses. They also help the teacher to assess the students’ understanding of content.

Encouraging students to respond

Many teachers allow less than one second before requiring a response to a question and therefore often answer the question themselves or rephrase the question (Hastings, 2003). The students only have time to react – they do not have time to think! If you wait for a few seconds before expecting answers, the students will have time to think. This has a positive effect on students’ achievement. By waiting after posing a question, there is an increase in:

- the length of students’ responses

- the number of students offering responses

- the frequency of students’ questions

- the number of responses from less capable students

- positive interactions between students.

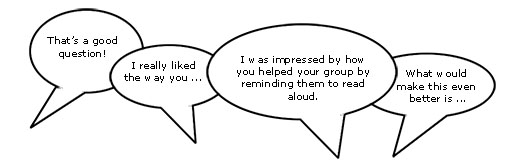

Your response matters

The more positively you receive all answers that are given, the more students will continue to think and try. There are many ways to ensure that wrong answers and misconceptions are corrected, and if one student has the wrong idea, you can be sure that many more have as well. You could try the following:

- Pick out the parts of the answers that are correct and ask the student in a supportive way to think a bit more about their answer. This encourages more active participation and helps your students to learn from their mistakes. The following comment shows how you might respond to an incorrect answer in a supportive way: ‘You were right about evaporation forming clouds, but I think we need to explore a bit more about what you said about rain. Can anyone else offer some ideas?’

- Write on the blackboard all the answers that the students give, and then ask the students to think about them all. What answers do they think are right? What might have led to another answer being given? This gives you an opportunity to understand the way that your students are thinking and also gives your students an unthreatening way to correct any misconceptions that they may have.

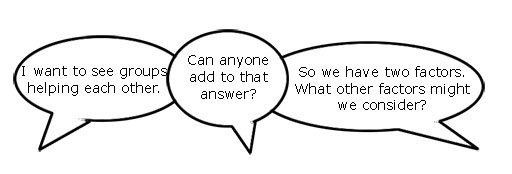

Value all responses by listening carefully and asking the student to explain further. If you ask for further explanation for all answers, right or wrong, students will often correct any mistakes for themselves, you will develop a thinking classroom and you will really know what learning your students have done and how to proceed. If wrong answers result in humiliation or punishment, then your students will stop trying for fear of further embarrassment or ridicule.

Improving the quality of responses

It is important that you try to adopt a sequence of questioning that doesn’t end with the right answer. Right answers should be rewarded with follow-up questions that extend the knowledge and provide students with an opportunity to engage with the teacher. You can do this by asking for:

- a how or a why

- another way to answer

- a better word

- evidence to substantiate an answer

- integration of a related skill

- application of the same skill or logic in a new setting.

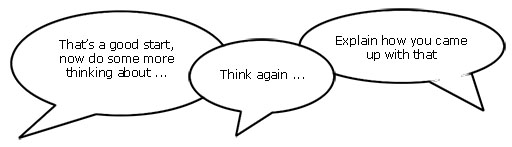

Helping students to think more deeply about (and therefore improve the quality of) their answer is a crucial part of your role. The following skills will help students achieve more:

- Prompting requires appropriate hints to be given – ones that help students develop and improve their answers. You might first choose to say what is right in the answer and then offer information, further questions and other clues. (‘So what would happen if you added a weight to the end of your paper aeroplane?’)

- Probing is about trying to find out more, helping students to clarify what they are trying to say to improve a disorganised answer or one that is partly right. (‘So what more can you tell me about how this fits together?’)

- Refocusing is about building on correct answers to link students’ knowledge to the knowledge that they have previously learnt. This broadens their understanding. (‘What you have said is correct, but how does it link with what we were looking at last week in our local environment topic?’)

- Sequencing questions means asking questions in an order designed to extend thinking. Questions should lead students to summarise, compare, explain or analyse. Prepare questions that stretch students, but do not challenge them so far that they lose the meaning of the questions. (‘Explain how you overcame your earlier problem. What difference did that make? What do you think you need to tackle next?’)

- Listening enables you to not just look for the answer you are expecting, but to alert you to unusual or innovative answers that you may not have expected. It also shows that you value the students’ thinking and therefore they are more likely to give thoughtful responses. Such answers could highlight misconceptions that need correcting, or they may show a new approach that you had not considered. (‘I hadn’t thought of that. Tell me more about why you think that way.’)

As a teacher, you need to ask questions that inspire and challenge if you are to generate interesting and inventive answers from your students. You need to give them time to think and you will be amazed how much your students know and how well you can help them progress their learning.

Remember, questioning is not about what the teacher knows, but about what the students know. It is important to remember that you should never answer your own questions! After all, if the students know you will give them the answers after a few seconds of silence, what is their incentive to answer?

References

Hastings, S. (2003) ‘Questioning’, TES Newspaper, 4 July. Available from: http://www.tes.co.uk/ article.aspx?storycode=381755 (accessed 22 September 2014).

Hattie, J. (2012) Visible Learning for Teachers: Maximising the Impact on Learning. Abingdon: Routledge.

Monitoring and giving feedback

Improving students’ performance involves constantly monitoring and responding to them, so that they know what is expected of them and they get feedback after completing tasks. They can improve their performance through your constructive feedback.

Monitoring

Effective teachers monitor their students most of the time. Generally, most teachers monitor their students’ work by listening and observing what they do in class. Monitoring students’ progress is critical because it helps them to:

- achieve higher grades

- be more aware of their performance and more responsible for their learning

- improve their learning

- predict achievement on state and local standardised tests.

It will also help you as a teacher to decide:

- when to ask a question or give a prompt

- when to praise

- whether to challenge

- how to include different groups of students in a task

- what to do about mistakes.

Students improve most when they are given clear and prompt feedback on their progress. Using monitoring will enable you to give regular feedback, letting your students know how they are doing and what else they need to do to advance their learning.

One of the challenges you will face is helping students to set their own learning targets, also known as self-monitoring. Students, especially struggling ones, are not used to having ownership of their own learning. But you can help any student to set their own targets or goals for a project, plan out their work and set deadlines, and self- monitor their progress. Practising the process and mastering the skill of self-monitoring will serve them well in school and throughout their lives.

Listening to and observing students

Most of the time, listening to and observing students is done naturally by teachers; it is a simple monitoring tool. For example, you may:

- listen to your students reading aloud

- listen to discussions in pair or groupwork

- observe students using resources outdoors or in the classroom

- observe the body language of groups as they work.

Make sure that the observations you collect are true evidence of student learning or progress. Only document what you can see, hear, justify or count.

As students work, move around the classroom in order to make brief observation notes. You can use a class list to record which students need more help, and also to note any emerging misunderstandings. You can use these observations and notes to give feedback to the whole class or prompt and encourage groups or individuals.

Giving feedback

Feedback is information that you give to a student about how they have performed in relation to a stated goal or expected outcome. Effective feedback provides the student with:

- information about what happened

- an evaluation of how well the action or task was performed

- guidance as to how their performance can be improved.

When you give feedback to each student, it should help them to know:

- what they can actually do

- what they cannot do yet

- how their work compares with that of others

- how they can improve.

It is important to remember that effective feedback helps students. You do not want to inhibit learning because your feedback is unclear or unfair. Effective feedback is:

- focused on the task being undertaken and the learning that the student needs to do

- clear and honest, telling the student what is good about their learning as well as what requires improvement

- actionable, telling the student to do something that they are able to do

- given in appropriate language that the student can understand

- given at the right time – if it’s given too soon, the student will think ‘I was just going to do that!’; too late, and the student’s focus will have moved elsewhere and they will not want to go back and do what is asked.

Whether feedback is spoken or written in the students’ workbooks, it becomes more effective if it follows the guidelines given below.

Using praise and positive language

When we are praised and encouraged, we generally feel a great deal better than when we are criticised or corrected. Reinforcement and positive language is motivating for the whole class and for individuals of all ages. Remember that praise must be specific and targeted on the work done rather than about the student themselves, otherwise it will not help the student progress. ‘Well done’ is non-specific, so it is better to say one of the following:

Using prompting as well as correction

The dialogue that you have with your students helps their learning. If you tell them that an answer is incorrect and finish the dialogue there, you miss the opportunity to help them to keep thinking and trying for themselves. If you give students a hint or ask them a further question, you prompt them to think more deeply and encourage them to find answers and take responsibility for their own learning. For example, you can encourage a better answer or prompt a different angle on a problem by saying such things as:

It may be appropriate to encourage other students to help each other. You can do this by opening your questions to the rest of the class with such comments as:

Correcting students with a ‘yes’ or ‘no’ might be appropriate to tasks such as spelling or number practice, but even here you can prompt students to look for emerging patterns in their answers, make connections with similar answers or open a discussion about why a certain answer is incorrect.

Self-correction and peer correction is effective and you can encourage this by asking students to check their own and each other’s work while doing tasks or assignments in pairs. It is best to focus on one aspect to correct at a time so that there is not too much confusing information.

Using groupwork

Groupwork is a systematic, active, pedagogical strategy that encourages small groups of students to work together for the achievement of a common goal. These small groups promote more active and more effective learning through structured activities.

The benefits of groupwork

Groupwork can be a very effective way of motivating your students to learn by encouraging them to think, communicate, exchange ideas and thoughts, and make decisions. Your students can both teach and learn from others: a powerful and active form of learning.

Groupwork is more than students sitting in groups; it involves working on and contributing to a shared learning task with a clear objective. You need to be clear about why you are using groupwork for learning and know why this is preferable to lecturing, pair work or to students working on their own. Thus groupwork has to be well-planned and purposeful.

Planning groupwork

When and how you use groupwork will depend on what learning you want to achieve by the end of the lesson. You can include groupwork at the start, the end or midway through the lesson, but you will need to allow enough time. You will need to think about the task that you want your students to complete and the best way to organise the groups.

As a teacher, you can ensure that groupwork is successful if you plan in advance:

- the goals and expected outcomes of the group activity

- the time allocated to the activity, including any feedback or summary task

- how to split the groups (how many groups, how many students in each group, criteria for groups)

- how to organise the groups (role of different group members, time required, materials, recording and reporting)

- how any assessment will be undertaken and recorded (take care to distinguish individual assessments from group assessments)

- how you will monitor the groups’ activities.

Groupwork tasks

The task that you ask your students to complete depends on what you what them to learn. By taking part in groupwork, they will learn skills such as listening to each other, explaining their ideas and working cooperatively. However, the main aim is for them to learn something about the subject that you are teaching. Some examples of tasks could include the following:

- Presentations: Students work in groups to prepare a presentation for the rest of the class. This works best if each group has a different aspect of the topic, so they are motivated to listen to each other rather than listening to the same topic several times. Be very strict about the time that each group has to present and decide on a set of criteria for a good presentation. Write these on the board before the lesson. Students can the use the criteria to plan their presentation and assess each other’s work. The criteria could include:

- Was the presentation clear?

- Was the presentation well-structured?

- Did I learn something from the presentation?

- Did the presentation make me think?

- Problem solving: Students work in groups to solve a problem or a series of problems. This could include conducting an experiment in science, solving problems in mathematics, analysing a story or poem in English, or analysing evidence in history.

- Creating an artefact or product: Students work in groups to develop a story, a piece of drama, a piece of music, a model to explain a concept, a news report on an issue or a poster to summarise information or explain a concept. Giving groups five minutes at the start of a new topic to create a brainstorm or mind map will tell you a great deal about what they already know, and will help you pitch the lesson at an appropriate level.

- Differentiated tasks: Groupwork is an opportunity to allow students of different ages or attainment levels to work together on an appropriate task. Higher attainers can benefit from the opportunity to explain the work, whereas lower attainers may find it easier to ask questions in a group than in a class, and will learn from their classmates.

- Discussion: Students consider an issue and come to a conclusion. This may require quite a bit of preparation on your part in order to make sure that the students have enough knowledge to consider different options, but organising a discussion or debate can be very rewarding for both you and them.

Organising groups

Groups of four to eight are ideal but this will depend on the size of your class, the physical environment and furniture, and the attainment and age range of your class. Ideally everyone in a group needs to see each other, talk without shouting and contribute to the group’s outcome.

- Decide how and why you will divide students into groups; for example, you may divide groups by friendship, interest or by similar or mixed attainment. Experiment with different ways and review what works best with each class.

- Plan any roles you will give to group members (for example, note taker, spokesperson, time keeper or collector of equipment), and how you will make this clear.

Managing groupwork

You can set up routines and rules to manage good groupwork. When you use groupwork regularly, students will know what you expect and find it enjoyable. Initially it is a good idea to work with your class to identify the benefits of working together in teams and groups. You should discuss what makes good groupwork behaviour and possibly generate a list of ‘rules’ that might be displayed; for example, ‘Respect for each other’, ‘Listening’, ‘Helping each other’, ‘Trying more than one idea’, etc.

It is important to give clear verbal instructions about the groupwork that can also be written on the blackboard for reference. You need to:

- direct your students to the groups they will work in according to your plan, perhaps designating areas in the classroom where they will work or giving instructions about moving any furniture or school bags

- be very clear about the task and write it on the board in short instructions or pictures. Allow your students to ask questions before you start.

During the lesson, move around to observe and check how the groups are doing. Offer advice where needed if they are deviating from the task or getting stuck.

- ‘Expert groups’: Give each group a different task, such as researching one way of generating electricity or developing a character for a drama. After a suitable time, re-organise the groups so that each new group is made up of one ‘expert’ from all the original groups. Then give them a task that involves collating knowledge from all the experts, such as deciding on what sort of power station to build or preparing a piece of drama.

- ‘Envoys’: If the task involves creating something or solving a problem, after a while, ask each group to send an envoy to another group. They could compare ideas or solutions to the problem and then report back to their own group. In this way, groups can learn from each other.

At the end of the task, summarise what has been learnt and correct any misunderstandings that you have seen. You may want to hear feedback from each group, or ask just one or two groups who you think have some good ideas. Keep students’ reporting brief and encourage them to offer feedback on work from other groups by identifying what has been done well, what was interesting and what might be developed further.

Even if you want to adopt groupwork in your classroom, you may at times find it difficult to organise because some students:

- are resistant to active learning and do not engage

- are dominant

- do not participate due to poor interpersonal skills or lack of confidence.

To become effective at managing groupwork it is important to reflect on all the above points, in addition to considering how far the learning outcomes were met and how well your students responded (did they all benefit?). Consider and carefully plan any adjustments you might make to the group task, resources, timings or composition of the groups.

Research suggests that learning in groups need not be used all the time to have positive effects on student achievement, so you should not feel obliged to use it in every lesson. You might want to consider using groupwork as a supplemental technique, for example as a break between a topic change or a jump-start for class discussion. It can also be used as an ice-breaker or to introduce experiential learning activities and problem solving exercises into the classroom, or to review topics.

Assessing progress and performance

Assessing students’ learning has two purposes:

- Summative assessment looks back and makes a judgement on what has already been learnt. It is often conducted in the form of tests that are graded, telling students their attainment on the questions in that test. This also helps in reporting outcomes.

- Formative assessment (or assessment for learning) is quite different, being more informal and diagnostic in nature. Teachers use it as part of the learning process, for example questioning to check whether students have understood something. The outcomes of this assessment are then used to change the next learning experience. Monitoring and feedback are part of formative assessment.

Formative assessment enhances learning because in order to learn, most students must:

- understand what they are expected to learn

- know where they are now with that learning

- understand how they can make progress (that is, what to study and how to study)

- know when they have reached the goals and expected outcomes.

As a teacher, you will get the best out of your students if you attend to the four points above in every lesson. Thus assessment can be undertaken before, during and after instruction:

- Before: Assessing before the teaching begins can help you identify what the students know and can do prior to instruction. It determines the baseline and gives you a starting point for planning your teaching. Enhancing your understanding of what your students know reduces the chance of re-teaching the students something they have already mastered or omitting something they possibly should (but do not yet) know or understand.

- During: Assessing during classroom teaching involves checking if students are learning and improving. This will help you make adjustments in your teaching methodology, resources and activities. It will help you understand how the student is progressing towards the desired objective and how successful your teaching is.

- After: Assessment that occurs after teaching confirms what students have learnt and shows you who has learnt and who still needs support. This will allow you to assess the effectiveness of your teaching goal.

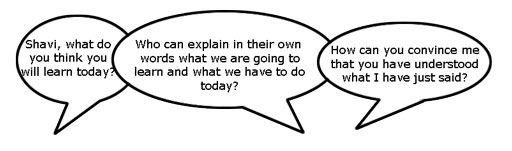

Before: being clear about what your students will learn

When you decide what the students must learn in a lesson or series of lessons, you need to share this with them. Carefully distinguish what the students are expected to learn from what you are asking them to do. Ask an open question that gives you the chance to assess whether they have really understood. For example:

Give the students a few seconds to think before they answer, or perhaps ask the students to first discuss their answers in pairs or small groups. When they tell you their answer, you will know whether they understand what it is they have to learn.

Before: knowing where students are in their learning

In order to help your students improve, both you and they need to know the current state of their knowledge and understanding. Once you have shared the intended learning outcomes or goals, you could do the following:

- Ask the students to work in pairs to make a mind map or list of what they already know about that topic, giving them enough time to complete it but not too long for those with few ideas. You should then review the mind maps or lists.

- Write the important vocabulary on the board and ask for volunteers to say what they know about each word. Then ask the rest of the class to put their thumbs up if they understand the word, thumbs down if they know very little or nothing, and thumbs horizontal if they know something.

Knowing where to start will mean that you can plan lessons that are relevant and constructive for your students. It is also important that your students are able to assess how well they are learning so that both you and they know what they need to learn next. Providing opportunities for your students to take charge of their own learning will help to make them life-long learners.

During: ensuring students’ progress in learning

When you talk to students about their current progress, make sure that they find your feedback both useful and constructive. Do this by:

- helping students know their strengths and how they might further improve

- being clear about what needs further development

- being positive about how they might develop their learning, checking that they understand and feel able to use the advice.

You will also need to provide opportunities for students to improve their learning. This means that you may have to modify your lesson plans to close the gap between where your students are now in their learning and where you wish them to be. In order to do this you might have to:

- go back over some work that you thought they knew already

- group students according to needs, giving them differentiated tasks

- encourage students to decide for themselves which of several resources they need to study so that they can ‘fill their own gap’

- use ‘low entry, high ceiling’ tasks so that all students can make progress – these are designed so that all students can start the task but the more able ones are not restricted and can progress to extend their learning.

By slowing the pace of lessons down, very often you can actually speed up learning because you give students the time and confidence to think and understand what they need to do to improve. By letting students talk about their work among themselves, and reflect on where the gaps are and how they might close them, you are providing them with ways to assess themselves.

After: collecting and interpreting evidence, and planning ahead

While teaching–learning is taking place and after setting a classwork or homework task, it is important to:

- find out how well your students are doing

- use this to inform your planning for the next lesson

- feed it back to students.

The four key states of assessment are discussed below.

Collecting information or evidence

Every student learns differently, at their own pace and style, both inside and outside the school. Therefore, you need to do two things while assessing students:

- Collect information from a variety of sources – from your own experience, the student, other students, other teachers, parents and community members.

- Assess students individually, in pairs and in groups, and promote self-assessment. Using different methods is important, as no single method can provide all the information you need. Different ways of collecting information about the students’ learning and progress include observing, listening, discussing topics and themes, and reviewing written class and homework.

Recording

In all schools across India the most common form of recording is through the use of report card, but this may not allow you to record all aspects of a student’s learning or behaviours. There are some simple ways of doing this that you may like to consider, such as:

- noting down what you observe while teaching–learning is going on in a diary/notebook/register

- keeping samples of students’ work (written, art, craft, projects, poems, etc.) in a portfolio

- preparing every student’s profile

- noting down any unusual incidents, changes, problems, strengths and learning evidences of students.

Interpreting the evidence

Once information and evidence have been collected and recorded, it is important to interpret it in order to form an understanding of how each student is learning and progressing. This requires careful reflection and analysis. You then need to act on your findings to improve learning, maybe through feedback to students or finding new resources, rearranging the groups, or repeating a learning point.

Planning for improvement

Assessment can help you to provide meaningful learning opportunities to every student by establishing specific and differentiated learning activities, giving attention to the students who need more help and challenging the students who are more advanced.

Using local resources

Many learning resources can be used in teaching – not just textbooks. If you offer ways to learn that use different senses (visual, auditory, touch, smell, taste), you will appeal to the different ways that students learn. There are resources all around you that you might use in your classroom, and that could support your students’ learning. Any school can generate its own learning resources at little or no cost. By sourcing these materials locally, connections are made between the curriculum and your students’ lives.

You will find people in your immediate environment who have expertise in a wide range of topics; you will also find a range of natural resources. This can help you to create links with the local community, demonstrate its value, stimulate students to see the richness and diversity of their environment, and perhaps most importantly work towards a holistic approach to student learning – that is, learning inside and outside the school.

Making the most of your classroom

People work hard at making their homes as attractive as possible. It is worth thinking about the environment that you expect your students to learn in. Anything you can do to make your classroom and school an attractive place to learn will have a positive impact on your students. There is plenty that you can do to make your classroom interesting and attractive for students – for example, you can:

- make posters from old magazines and brochures

- bring in objects and artefacts related to the current topic

- display your students’ work

- change the classroom displays to keep students curious and prompt new learning.

Using local experts in your classroom

If you are doing work on money or quantities in mathematics, you could invite market traders or dressmakers into the classroom to come to explain how they use maths in their work. Alternatively, if you are exploring patterns and shapes in art, you could invite maindi [wedding henna] designers to the school to explain the different shapes, designs, traditions and techniques. Inviting guests works best when the link with educational aims is clear to everyone and there are shared expectations of timing.

You may also have experts within the school community (such as the cook or the caretaker) who can be shadowed or interviewed by students related to their learning; for example, to find out about quantities used in cooking, or how weather conditions impact on the school grounds and buildings.

Using the outside environment

Outside your classroom there is a whole range of resources that you can use in your lessons. You could collect (or ask your class to collect) objects such as leaves, spiders, plants, insects, rocks or wood. Bringing these resources in can lead to interesting classroom displays that can be referred to in lessons. They can provide objects for discussion or experimentation such as an activity in classification, or living or not-living objects. There are also resources such as bus timetables or advertisements that might be readily available and relevant to your local community – these can be turned into learning resources by setting tasks to identify words, compare qualities or calculate journey times.

Objects from outside can be brought into the classroom – but the outside can also be an extension of your classroom. There is usually more room to move outside and for all students to see more easily. When you take your class outside to learn, they can do activities such as:

- estimating and measuring distances

- demonstrating that every point on a circle is the same distance from the central point

- recording the length of shadows at different times of the day

- reading signs and instructions

- conducting interviews and surveys

- locating solar panels

- monitoring crop growth and rainfall.

Outside, their learning is based on realities and their own experiences, and may be more transferable to other contexts.

If your work outside involves leaving the school premises, before you go you need to obtain the school leader’s permission, plan timings, check for safety and make rules clear to the students. You and your students should be clear about what is to be learnt before you depart.

Adapting resources

You may want to adapt existing resources to make them more appropriate to your students. These changes may be small but could make a big difference, especially if you are trying to make the learning relevant to all the students in the class. You might, for example, change place and people names if they relate to another state, or change the gender of a person in a song, or introduce a child with a disability into a story. In this way you can make the resources more inclusive and appropriate to your class and their learning.

Work with your colleagues to be resourceful: you will have a range of skills between you to generate and adapt resources. One colleague might have skills in music, another in puppet making or organising outdoor science. You can share the resources you use in your classroom with your colleagues to help you all generate a rich learning environment in all areas of your school.

Storytelling, songs, role play and drama

Students learn best when they are actively engaged in the learning experience. Your students can deepen their understanding of a topic by interacting with others and sharing their ideas. Storytelling, songs, role play and drama are some of the methods that can be used across a range of curriculum areas, including maths and science.

Storytelling

Stories help us make sense of our lives. Many traditional stories have been passed down from generation to generation. They were told to us when we were young and explain some of the rules and values of the society that we were born into.

Stories are a very powerful medium in the classroom: they can:

- be entertaining, exciting and stimulating

- take us from everyday life into fantasy worlds

- be challenging

- stimulate thinking about new ideas

- help explore feelings

- help to think through problems in a context that is detached from reality and therefore less threatening.

When you tell stories, be sure to make eye contact with students. They will enjoy it if you use different voices for different characters and vary the volume and tone of your voice by whispering or shouting at appropriate times, for example. Practise the key events of the story so that you can tell it orally, without a book, in your own words. You can bring in props such as objects or clothes to bring the story to life in the classroom. When you introduce a story, be sure to explain its purpose and alert students to what they might learn. You may need to introduce key vocabulary or alert them to the concepts that underpin the story. You may also consider bringing a traditional storyteller into school, but remember to ensure that what is to be learnt is clear to both the storyteller and the students.

Storytelling can prompt a number of student activities beyond listening. Students can be asked to note down all the colours mentioned in the story, draw pictures, recall key events, generate dialogue or change the ending. They can be divided into groups and given pictures or props to retell the story from another perspective. By analysing a story, students can be asked to identify fact from fiction, debate scientific explanations for phenomena or solve mathematical problems.

Asking the students to devise their own stories is a very powerful tool. If you give them structure, content and language to work within, the students can tell their own stories, even about quite difficult ideas in maths and science. In effect they are playing with ideas, exploring meaning and making the abstract understandable through the metaphor of their stories.

Songs

The use of songs and music in the classroom may allow different students to contribute, succeed and excel. Singing together has a bonding effect and can help to make all students feel included because individual performance is not in focus. The rhyme and rhythm in songs makes them easy to remember and helps language and speech development.

You may not be a confident singer yourself, but you are sure to have good singers in the class that you can call on to help you. You can use movement and gestures to enliven the song and help to convey meaning. You can use songs you know and change the words to fit your purpose. Songs are also a useful way to memorise and retain information – even formulas and lists can be put into a song or poem format. Your students might be quite inventive at generating songs or chants for revision purposes.

Role play

Role play is when students have a role to play and, during a small scenario, they speak and act in that role, adopting the behaviours and motives of the character they are playing. No script is provided but it is important that students are given enough information by the teacher to be able to assume the role. The students enacting the roles should also be encouraged to express their thoughts and feelings spontaneously.

Role play has a number of advantages, because it:

- explores real-life situations to develop understandings of other people’s feelings

- promotes development of decision making skills

- actively engages students in learning and enables all students to make a contribution

- promotes a higher level of thinking.

Role play can help younger students develop confidence to speak in different social situations, for example, pretending to shop in a store, provide tourists with directions to a local monument or purchase a ticket. You can set up simple scenes with a few props and signs, such as ‘Café’, ‘Doctor’s Surgery’ or ‘Garage’. Ask your students, ‘Who works here?’, ‘What do they say?’ and ‘What do we ask them?’, and encourage them to interact in role these areas, observing their language use.

Role play can develop older students’ life skills. For example, in class, you may be exploring how to resolve conflict. Rather than use an actual incident from your school or your community, you can describe a similar but detached scenario that exposes the same issues. Assign students to roles or ask them to choose one for themselves. You may give them planning time or just ask them to role play immediately. The role play can be performed to the class, or students could work in small groups so that no group is being watched. Note that the purpose of this activity is the experience of role playing and what it exposes; you are not looking for polished performances or Bollywood actor awards.

It is also possible to use role play in science and maths. Students can model the behaviours of atoms, taking on characteristics of particles in their interactions with each other or changing their behaviours to show the impact of heat or light. In maths, students can role play angles and shapes to discover their qualities and combinations.

Drama

Using drama in the classroom is a good strategy to motivate most students. Drama develops skills and confidence, and can also be used to assess what your students understand about a topic. A drama about students’ understanding of how the brain works could use pretend telephones to show how messages go from the brain to the ears, eyes, nose, hands and mouth, and back again. Or a short, fun drama on the terrible consequences of forgetting how to subtract numbers could fix the correct methods in young students’ minds.

Drama often builds towards a performance to the rest of the class, the school or to the parents and the local community. This goal will give students something to work towards and motivate them. The whole class should be involved in the creative process of producing a drama. It is important that differences in confidence levels are considered. Not everyone has to be an actor; students can contribute in other ways (organising, costumes, props, stage hands) that may relate more closely to their talents and personality.

It is important to consider why you are using drama to help your students learn. Is it to develop language (e.g. asking and answering questions), subject knowledge (e.g. environmental impact of mining), or to build specific skills (e.g. team work)? Be careful not to let the learning purpose of drama be lost in the goal of the performance.

Acknowledgements

This content is made available under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike licence (http://creativecommons.org/ licenses/ by-sa/ 3.0/), unless identified otherwise. The licence excludes the use of the TESS-India, OU and UKAID logos, which may only be used unadapted within the TESS-India project.

Every effort has been made to contact copyright owners. If any have been inadvertently overlooked the publishers will be pleased to make the necessary arrangements at the first opportunity.

Key resources include contributions from: Deborah Cooper, Beth Erling, Jo Mutlow, Clare Lee, Kris Stutchbury, Freda Wolfenden and Sandhya Paranjpe.