Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Thursday, 5 February 2026, 9:24 AM

TI-AIE: Letters and sounds of English

What this unit is about

This unit is about classroom activities to learn and practise English sounds, letters and words.

We know that an important step in learning to read in English is to know what sounds the letters of the English alphabet make. Of course, this is not all that is involved in learning to read – teaching reading must be done with a focus on meaning. The activities in this unit are designed to help you keep this focus on meaning as you and your students practise English sounds and letters.

What you can learn in this unit

- To practise English letters and sounds at your level.

- To practise English letters and sounds in the classroom with students.

- To plan English sound, letter and word activities.

1 English pronunciation

In the first activity, you will work through an English pronunciation guide, at your level.

Activity 1: English letters and sounds

The names of English letters can be very different from the sounds they make in words.

Say the name of this English letter ‘b’. It will sound something like ‘bee’. What are some English words that start with this letter? You might think of ‘bag’, ‘bus’ or ‘bell’. Say these words aloud.

When you say these words aloud, you will hear the sound of the letter is something like ‘bh’. Try to say just the sound of ‘b’, and hear the sound in words such as ‘bag’ and ‘boy’. Hear the difference between the name of the letter and the sound of the letter.

Try this again and say the name the English letter ‘r’. What are some words that start with ‘r’? Say these words aloud.

What is the sound that ‘r’ makes in these words? Hear how the letter name ‘r’ sounds something like ‘are’, but the sound is something like ‘rrr’.

With the vowels of English (‘a’, ‘e’, ‘i’, ‘o’, ‘u’), the sounds change depending on the word they are in.

Go to Resource 1 and work through the letters and sounds for yourself. How would you evaluate your confidence and pronunciation?

A good way to improve your pronunciation in English is to hear the sounds of English as much as possible. Try to listen to English on the radio. Even if you cannot understand everything that is spoken or sung, listen and try to say the sounds of English.

In the two case studies that follow, you can see how teachers introduce English letters and sounds to students.

Case Study 1: Parveen teaches the sound of ‘b’

Parveen is a Class I teacher.

I had some small objects like a bag, a balloon and a brush, and some pictures of things that start with ‘b’, like boat, bicycle and buffalo. I also had piece of cloth that was blue.

I started the lesson by saying, ‘Today we will focus on the letter “b” and the sound of “b”. Let’s all learn some words in English that start with the sound “b”.’

Sometimes students came up with words in Hindi that start with the ‘b’ sound. When they did this, I confirmed that the sound in our language is similar to the English ‘b’. I also liked to point out the students in the class who have names that start with the ‘b’ sound, like Baldev and Bala.

Once we had a list of words that start with ‘b’, I created a very simple story from the list: Bala went to the market to buy a cricket bag, a new bag for her school books, a brush for her hair and a basket to keep the brush in. But in the end, she saw a blue balloon and she bought that instead.

Then I had the students draw pictures of the words that start with the sound ’b’ and tell their own story to these pictures.

Pause for thought

|

2 Letters, sounds and words in the classroom

Case Study 2: Nanda uses the textbook and flash cards

Nanda teaches Class II

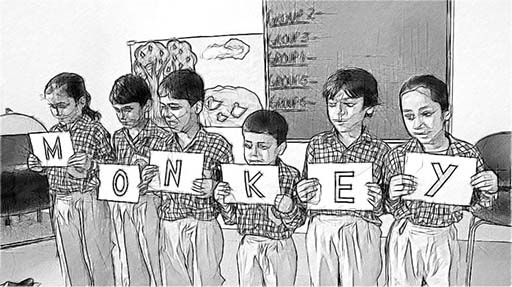

I made a set of English letter cards (Figure 1). These cards have all the letters of the English alphabet and also some letter combinations such as ‘ch’, ‘sh’, ‘ph’ and ‘th’. It didn’t take long to make these cards and they always are useful.

I take the textbook lesson and I make another set of flash cards for the key vocabulary in the unit. On one side of the cards I write the words, and on the other side I draw pictures – or find some in magazines – of the words (for example, ‘apple’, ‘mango’, ‘banana’, ‘chapati’, ‘fish’).

Before I teach the lesson, I practise saying the words in English myself so that I feel confident to say them. Sometimes I check my pronunciation with a friend who has better English than me.

In class, I hold up the picture cards and say the word for each of the pictures. I tell the students, ‘Repeat after me … mango’. I do this a few times. I then do the activity again, this time stressing the first sound of each of the words when I say it; for example, ‘m – mango’. I try to ask students short questions using the words, so they can hear them repeated in a sentence. I ask, for example, ‘Do you like mango?’ – and they can answer yes or no.

Then I show students the letter cards and have them practise pronouncing the sounds such as ‘a’, ‘m’, ‘b’, ‘ch’ and ‘f’ when I hold up the cards. Finally, I hold up one of the picture cards and ask students to tell me the sound that it starts with. So when I hold up a card with a mango on it, they can say the sound of ‘m’ or the name of the letter ‘m’ – both are correct.

During the week, I rotate small groups of children to play a game with the two sets of flash cards – matching the picture and word cards to the letter cards. I work with a group of children who have difficulty in making the letter/sound connections. [See Resource 2, ‘Using groupwork’, to learn more about how to organise and manage students in groups.]

In these activities I encourage students to read the letters and say the sound of the letters, and to think about the sounds they make. I also have them read and say the whole words. I think it is important to make them think about the meaning of the words and to use these words in short sentences.

Pause for thought

|

Students can be taught to memorise and chant letters and words, especially when lessons are predictable and repetitive. This does not necessarily mean students understand what they are ‘reading’. Nanda’s classroom activities are varied and interactive. She encourages students to participate, and to make guesses, and she does not over-correct them. Nanda does not teach letters and sounds in isolation – she helps students recognise letters and sounds in words that are meaningful to them (such as ‘mango’ and ‘chapati’).

Activity 2: Letters, sounds and words

Now go to Resource 3. Read through these games and activities. Choose one activity to try out with your class, either from Resource 3 or from Case Studies 1 and 2 above.

Discuss your choice with a colleague if possible. Will you adapt the game or activity in some way, to suit the needs of your class?

Link the activity to the vocabulary in the textbook lesson you are teaching. Try out the activity with a colleague before you do it with students.

The main aim of these activities is to teach letters and sounds, but it is also important to make sure that the students relate these sounds to English words and that they understand the meaning of these words. How will you ensure this?

Do your chosen activity with students. Afterwards, think about what went well, and what you could do differently next time.

It is a good idea to monitor students’ progress in learning English letters and sounds over time, and how they apply their letter/sound knowledge to their reading and writing. A simple tick list or table can help you keep track of individual student’s progress, so you can build their records of achievement:

- Can recite the alphabet.

- Can recognise letters.

- Can recognise letters not in alphabetical order.

- Can link letter names to sounds.

- Can link letter patterns to sounds (e.g. ‘ch’, ‘sh’, ‘th’).

- Can use letter/sound knowledge to read simple words.

- Can use letter/sound knowledge to write simple words.

- Can read words on flash cards.

- Can read words in a sentence.

3 Words and spellings

Hearing and using rhyming words helps students to recognise letter and sound patterns in English. Textbooks contain lessons that ask students to look for selected short words within a longer text. You can adapt these lessons to help students identify rhyming words.

Activity 3 uses an extract from a Class I textbook. The words at the beginning of the extract are rhyming words. One word in each pair occurs in the story, and students must look for these words.

Activity 3: Using the textbook for word work

This activity helps students to use words in a meaningful context. Try it yourself.

Read and say these words aloud. Then circle the words you find in the story.

| few | bed | see | back |

| new | red | tree | sack |

Ravi is crying. ‘I CAN’T SEE MY NEW BAG!’ he says.

‘Is your bag new?’ asks the teacher.

‘Yes, it is,’ says Ravi.

‘Is it red and yellow?’

‘Yes, it is.’

‘I can see it,’ says the teacher.

‘Where?’

‘It’s on your back!’

Now choose a short extract from your textbook and create an activity like the one above, making a set of rhyming words to go with extract.

Use the extract and rhyming words you prepared from the textbook with your students. Demonstrate to the students how to work through the activity, doing the first word yourself.

If the extract you choose is a dialogue, read the dialogue aloud, helping to ensure that the students understand it. You could act out the two different parts using different voices or ask a student to act it out with you. Use mime and gesture, and any classroom objects, to ensure that students understand the meaning.

As students work through this activity, you can evaluate their skills in recognising and reading English letter patterns. Encourage them to read out the extract and hear the rhyming words spoken aloud.

In the next activity, you look at the relationship between letters, sounds and spellings in English.

Activity 4: Using letters and sounds to spell

This is an activity for you.

Read the beginning of a story in English, written by an eight-year-old girl:

Ther ouns was two flawrs. Oun was pink and the othr was prpul. Thae did

not like ech athr becuse thae whr difrint culrs. Oun day thae had a fite.

Could you read this story and understand it? How would you assess it?

The student is using all she knows about the letters and sounds of English to write her story. She is using her best judgements about how to spell. These invented spellings are a stage in reading and writing development. It is important to see students’ invented spellings as part of the developmental process of literacy – they are not errors or mistakes.

When your young students begin to write in English, they are likely to go through these stages of spelling development:

- Using a single letter to represent a word or sound; for example, ‘u’ for ‘you’, or ‘m’ for ‘am’.

- Using a letter or group of letters to represent a word; for example, ‘kam’ for ‘come’, ‘lv’ for ‘love’ and ‘dis iz a kat’ for ‘this is a cat’.

Now look at some of your students’ English writing and see if you can find invented spellings in English.

What has been your response to these invented spellings? Do you correct them right away? How do students respond to your corrections? Do you ever ask students to explain their English spellings to you, in their home language?

It is important that you do not over-correct invented spellings, because students are experimenting with the letters and sounds of the language they are learning. Students acquire ideas about spelling as they hear language, read and write. Over time, with exposure and practice, their spelling will become increasingly correct.

4 Summary

In this unit you have looked at ways to develop your own and your students’ knowledge of English letters and sounds through activities. It is good practice to embed your teaching of letters and sounds in reading and writing, so that students do not learn letters in isolation. If you can, listen to English spoken or sung on the radio to improve your own pronunciation. Think about the possibility of using a radio for regular English listening activities in your classroom. Could you show students English letters on a computer keyboard or on a mobile phone?

Other Elementary English teacher development units on this topic are:

- Classroom routines

- Using the textbook creatively

- Songs, rhymes and word play

- Storytelling

- Shared reading.

Resources

Resource 1: Pronunciation guide

Of course, English is not your first language and you can’t expect to have perfect pronunciation. Although you might read and write English, you may not have heard much English and may be shy about speaking it. Listening to the national radio and television programmes in English is one way of brushing up your pronunciation. Another way is using the pronunciation guide in a good dictionary.

If you want your students to speak English so that they can be understood well, you must try to have the best pronunciation you can.

Use the pronunciation guide below to check how well you know the main vowel and consonant sounds or combinations of these in English. Tick the sounds that you are less confident about, and take steps to hear and speak words that contain these sounds.

Single vowels

short a (mat, ant)

short e (bed, end)

short i (fish, it)

short o (shop, hot)

short u (bus, under)

long a (race, late)

long e (these, scene)

long i (time, like)

long o (home, bone)

long u (tune, use)

Pairs of vowels making a new sound

ai (train, paint)

ea (leaf, dream)

ee (sheep, been)

oa (boat, road)

oo (look, good)

ou (ground, out)

Vowel changed by a consonant

ar (car, park)

er (her, verse)

ir (bird, shirt)

or (short, or)

ur (ture, purple)

ow (town, shower/show, low)

ay (day, play)

Pairs of consonants making new sounds

th – unvoiced (three, thanks)

th – voiced (this, mother)

sh (she, short)

ch (which, chicken)

ph (phone, elephant)

gh (laugh, enough, high, although)

wh (what, why)

Others

all (all, fall)

qu (queen, quick)

y (sunny, happy)

ing (sing, talking)

Resource 2: Using groupwork

Groupwork is a systematic, active, pedagogical strategy that encourages small groups of students to work together for the achievement of a common goal. These small groups promote more active and more effective learning through structured activities.

The benefits of groupwork

Groupwork can be a very effective way of motivating your students to learn by encouraging them to think, communicate, exchange ideas and thoughts, and make decisions. Your students can both teach and learn from others: a powerful and active form of learning.

Groupwork is more than students sitting in groups; it involves working on and contributing to a shared learning task with a clear objective. You need to be clear about why you are using groupwork for learning and know why this is preferable to lecturing, pair work or to students working on their own. Thus groupwork has to be well-planned and purposeful.

Planning groupwork

When and how you use groupwork will depend on what learning you want to achieve by the end of the lesson. You can include groupwork at the start, the end or midway through the lesson, but you will need to allow enough time. You will need to think about the task that you want your students to complete and the best way to organise the groups.

As a teacher, you can ensure that groupwork is successful if you plan in advance:

- the goals and expected outcomes of the group activity

- the time allocated to the activity, including any feedback or summary task

- how to split the groups (how many groups, how many students in each group, criteria for groups)

- how to organise the groups (role of different group members, time required, materials, recording and reporting)

- how any assessment will be undertaken and recorded (take care to distinguish individual assessments from group assessments)

- how you will monitor the groups’ activities.

Groupwork tasks

The task that you ask your students to complete depends on what you what them to learn. By taking part in groupwork, they will learn skills such as listening to each other, explaining their ideas and working cooperatively. However, the main aim is for them to learn something about the subject that you are teaching. Some examples of tasks could include the following:

- Presentations: Students work in groups to prepare a presentation for the rest of the class. This works best if each group has a different aspect of the topic, so they are motivated to listen to each other rather than listening to the same topic several times. Be very strict about the time that each group has to present and decide on a set of criteria for a good presentation. Write these on the board before the lesson. Students can the use the criteria to plan their presentation and assess each other’s work. The criteria could include:

- Was the presentation clear?

- Was the presentation well-structured?

- Did I learn something from the presentation?

- Did the presentation make me think?

- Problem solving: Students work in groups to solve a problem or a series of problems. This could include conducting an experiment in science, solving problems in mathematics, analysing a story or poem in English, or analysing evidence in history.

- Creating an artefact or product: Students work in groups to develop a story, a piece of drama, a piece of music, a model to explain a concept, a news report on an issue or a poster to summarise information or explain a concept. Giving groups five minutes at the start of a new topic to create a brainstorm or mind map will tell you a great deal about what they already know, and will help you pitch the lesson at an appropriate level.

- Differentiated tasks: Groupwork is an opportunity to allow students of different ages or attainment levels to work together on an appropriate task. Higher attainers can benefit from the opportunity to explain the work, whereas lower attainers may find it easier to ask questions in a group than in a class, and will learn from their classmates.

- Discussion: Students consider an issue and come to a conclusion. This may require quite a bit of preparation on your part in order to make sure that the students have enough knowledge to consider different options, but organising a discussion or debate can be very rewarding for both you and them.

Organising groups

Groups of four to eight are ideal but this will depend on the size of your class, the physical environment and furniture, and the attainment and age range of your class. Ideally everyone in a group needs to see each other, talk without shouting and contribute to the group’s outcome.

- Decide how and why you will divide students into groups; for example, you may divide groups by friendship, interest or by similar or mixed attainment. Experiment with different ways and review what works best with each class.

- Plan any roles you will give to group members (for example, note taker, spokesperson, time keeper or collector of equipment), and how you will make this clear.

Managing groupwork

You can set up routines and rules to manage good groupwork. When you use groupwork regularly, students will know what you expect and find it enjoyable. Initially it is a good idea to work with your class to identify the benefits of working together in teams and groups. You should discuss what makes good groupwork behaviour and possibly generate a list of ‘rules’ that might be displayed; for example, ‘Respect for each other’, ‘Listening’, ‘Helping each other’, ‘Trying more than one idea’, etc.

It is important to give clear verbal instructions about the groupwork that can also be written on the blackboard for reference. You need to:

- direct your students to the groups they will work in according to your plan, perhaps designating areas in the classroom where they will work or giving instructions about moving any furniture or school bags

- be very clear about the task and write it on the board in short instructions or pictures. Allow your students to ask questions before you start.

During the lesson, move around to observe and check how the groups are doing. Offer advice where needed if they are deviating from the task or getting stuck.

You might want to change the groups during the task. Here are two techniques to try when you are feeling confident about groupwork – they are particularly helpful when managing a large class:

- ‘Expert groups’: Give each group a different task, such as researching one way of generating electricity or developing a character for a drama. After a suitable time, re-organise the groups so that each new group is made up of one ‘expert’ from all the original groups. Then give them a task that involves collating knowledge from all the experts, such as deciding on what sort of power station to build or preparing a piece of drama.

- ‘Envoys’: If the task involves creating something or solving a problem, after a while, ask each group to send an envoy to another group. They could compare ideas or solutions to the problem and then report back to their own group. In this way, groups can learn from each other.

At the end of the task, summarise what has been learnt and correct any misunderstandings that you have seen. You may want to hear feedback from each group, or ask just one or two groups who you think have some good ideas. Keep students’ reporting brief and encourage them to offer feedback on work from other groups by identifying what has been done well, what was interesting and what might be developed further.

Even if you want to adopt groupwork in your classroom, you may at times find it difficult to organise because ome students:

- are resistant to active learning and do not engage

- are dominant

- do not participate due to poor interpersonal skills or lack of confidence.

To become effective at managing groupwork it is important to reflect on all the above points, in addition to considering how far the learning outcomes were met and how well your students responded (did they all benefit?). Consider and carefully plan any adjustments you might make to the group task, resources, timings or composition of the groups.

Research suggests that learning in groups need not be used all the time to have positive effects on student achievement, so you should not feel obliged to use it in every lesson. You might want to consider using groupwork as a supplemental technique, for example as a break between a topic change or a jump-start for class discussion. It can also be used as an ice-breaker or to introduce experiential learning activities and problem solving exercises into the classroom, or to review topics.

Resource 3: Letter, sound and word games

Choose a game and practise it with a colleague. Then try it out with your class.

‘Letters and Sounds’

Oral activity: Say the sound of a letter (for example, ‘rrrr’). Students must say words that start with that letter (for example, ‘rain’ or ‘rabbit’). Let them give responses in English or in Hindi.

Reading and listening activity: Write a letter on the board, for example, the letter ‘f’. Then say the sound of a different letter, for example the sound of ‘g’ (‘gh’) or a word that starts with the letter such as ‘goat’. The students must raise their hands if they think the letter or word you say matches the letter on the board. You can monitor which students are following the lesson. Try this with different letters, sounds and words.

‘Guess What I See?’

This game can be used with any level. Choose a word for something that you can see in the classroom (e.g. ‘pen’, ‘door’, ‘chair’). Don’t say which word it is. It should be a word at least most of the class will know. Then say, ‘Guess what I see? I see something beginning with … and then say the sound of the first letter, for example ‘p’, ‘d’ or ‘ch’. Students must guess the words. Practise the pronunciation of each word as it is guessed.

When students are familiar with the game, they can play it in groups or pairs, or students can take turns to lead the class.

‘Word Ladder’

Students can refer to their textbooks for this activity. This game starts by listing one word, such as ‘pen’. The next player or team has to say a word that starts with the final sound of the previous word; for example, ‘nest’. The game proceeds further, with the next player or team saying a word that begins with the sound ‘t’, and so on.

‘Is it the Same?’

Divide the class into two or more teams. Write a selection of around 12 words from recent lessons on the board. Point to one word (for example, ‘page’) and say a word. The word you say can be the word you are pointing at or another word with some similarities (such as ‘play’ or ‘plane’). Choose a student, who must then say ‘It is the same’ or ‘It is not the same’, depending on whether the word you’ve pointed to is the same as the word you’ve said. A correct answer wins one point for the team. Now ask a student on the other team.

Continue in this way. After a while, wipe the first group of words off the board, and write up another group of words and repeat. Repeat again as required, keeping the scores on the board.

‘Paint the Word’

For young students, this game can be used with single letters of the alphabet. For more advanced students, the activity can be used with words.

Mime painting a letter or word from recent lessons and/or the current lesson, using big, bold strokes, as if holding a paint brush as high above your head as you can. Remember to face away from the students, as if you are writing on the blackboard, or your writing will be back to front from the students’ point of view! Ask who can guess the letter or word. The first student to guess correctly wins a round of applause from the rest of the class. Continue with further letters or words, and then ask the students to take turns to mime painting the letters and words themselves.

‘Guess the Word’

Start writing a word from recent lessons or the current lesson on the board. When you have written the first two letters, invite guesses about the word. If nobody is correct, add a third letter, and so on, until somebody guesses the word correctly. If you wish, the first student to guess the word can come to the board, and take over the role of writing (you may need to help with this, however).

‘Sit Down!’

This activity can be used with any level and using any letter or pair of letters. The example below uses ‘sh’.

Write the letters ‘sh’ on the board. Everybody must stand. Say a word from the current and previous lessons. If it contains ‘sh’, the students must sit down; if not, they remain standing. If standing up or sitting down will be difficult in your classroom, students can raise and lower their hands instead. Responding physically in a lesson can be a fun and memorable way to learn.

‘Alphabet Board Game’

This is a game for groups and it is appropriate for more advanced learners, from Class II onwards, who have been introduced to the names of letters, as well as their sounds. You will need to prepare the resources.

On a large piece of cardboard, write out the letters of the alphabet in sequence, preparing one board game per group. Give the students a die per group. They roll a number and move to the appropriate letter. When they land on a letter, they must say the name of the letter, its sound, and also a word that starts with that letter.

Additional resources

- Karadi Tales: http://www.karaditales.com/

- National Book Trust India: http://www.nbtindia.gov.in/

- NCERT textbooks: http://www.ncert.nic.in/ NCERTS/ textbook/ textbook.htm

- Teachers of India classroom resources: http://www.teachersofindia.org/ en

- Phonic stories, RV VSEI Resource Centre: http://www.rvec.in/

References

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements

This content is made available under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike licence (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/), unless identified otherwise. The licence excludes the use of the TESS-India, OU and UKAID logos, which may only be used unadapted within the TESS-India project.

Every effort has been made to contact copyright owners. If any have been inadvertently overlooked the publishers will be pleased to make the necessary arrangements at the first opportunity.

Video (including video stills): thanks are extended to the teacher educators, headteachers, teachers and students across India who worked with The Open University in the productions.