Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Thursday, 5 February 2026, 4:16 AM

TI-AIE: Mark-making and early writing

What this unit is about

This unit examines young children’s early writing. When children start to make marks on paper, it means they are beginning to explore and understand writing as a form of communication. In this unit, you will focus on ways to support young students’ writing practice in English. Please note that the activities and resources in this unit are appropriate for early writing development in any language.

What you can learn in this unit

- To identify indicators of early writing development.

- To organise writing resources.

- To plan writing activities and routines to use with your class.

1 What is emergent writing?

You start by considering the early writing process.

Activity 1: What is emergent writing?

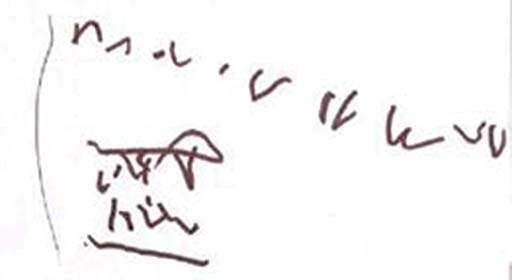

Look at Figure 1, which shows ‘writing’ by a four-year-old girl. She confidently told her pre-school teacher that she was writing numbers and letters. How would you evaluate this as a piece of writing, or do you think it is merely scribbling? Talk to other teachers in your school about this piece of writing. How do they respond to it?

In its early stages, emergent writing may appear to be little more than scribbles on a page or a cluster of unrelated symbols and shapes. But the girl who did this shows knowledge and awareness of what writing is. She knows that:

- marks on the paper can represent numbers and letters

- writing conveys information

- writing is meant to be read.

Very young children who see writing at home, in school or in the community will start to understand that writing has many different meanings and purposes. They will try to reproduce this, copying what they see and also making their own marks without copying. When they do this they are becoming writers, communicating their ideas on paper. When young students start to write in English, they must pay attention to five things at the same time:

- finger control

- letter formation

- the letters, sounds and shapes of English

- the meaning of English words

- the overall message of their writing.

Pause for thought

|

2 Students’ writing

Activity 2: Where can students write?

Look at Figure 2. Which of the activities would be possible to do with your students in your classroom and school? Discuss this with a fellow teacher if possible. Think of the spaces in your classroom, and outside your classroom, where students could practise writing.

Now look at the checklist below.

- What to write with? Pencils, pens, paint, chalk, brushes, sticks.

- What to write on? Sand, pavement, chart paper, recycled paper, board, walls, floors, dirt, notebooks, small books made from recycled paper.

Discuss this checklist with a fellow teacher, if possible. What resources are available in your school?

Think of the writing resources you have, inside and outside the classroom, to encourage students to practise. Can you see any areas inside or outside your classroom where students could make marks and write freely?

Plan some sessions in your classroom over the next two to three weeks where you use one or more of the ideas given here. Discuss your plans with a fellow teacher or with your headteacher. You could organise lessons where groups of students do free writing in rotation throughout the week.

Activity 3: Writing for different purposes

Do you have your students write any of the following in your class? Tick any that you have your students write:

- lists

- greeting cards

- birthday cards

- postcards

- letters

- invitations

- thank you notes

- menus

- advertisements

- recipes

- signs

- notes

- reminders

- labels

- tickets

- catalogues

- programmes

- emails

- text messages

- multimedia presentations, i.e. posters.

How are all of these different to writing stories or poems? Why are they written and who are they for? Where do we see them?

Do you think your students would enjoy writing any of the above? Why or why not? Can you find recent textbook lessons that refer to any of these kinds of writing?

3 Writing postcards

Outside school, there are many different types of writing that people read for different purposes. Writing often includes illustrations and design to make the message more exciting, dramatic or clear. Students enjoy writing activities that mirror the writing they experience in real life.

But much of the writing that students do in school is not read by anyone other than the teacher. In Case Study 1, a teacher has students do writing that is read by others outside the school.

Case Study 1: Mrs Sonali’s class sends postcards

Mrs Sonali teaches Class III in a government primary school.

One day a student asked me, ‘How does a letter know how to get to me?’ I asked the class how many students had ever sent or received a real letter or postcard in the post. No one put their hand up. I brought in some postcards I had at home, to show students what they look like, where the address goes and where the messages goes, and where the stamp is put.

I had students make their own postcards, using heavy card. Students drew their own pictures on one side, and their home address and a very short, simple message in English on the other side. I was able to observe that some students could write independently, and others needed much more help.

I asked the headteacher for money to purchase stamps for each postcard and the whole class walked to the post office to post their cards. My cousin works at the post office and he arranged for them to speak to the postman about his work and how post is delivered. A week later, students were very excited when they received their postcards at home, bringing them into school to show me.

I have adapted this activity. For example, I have students make birthday cards or cards for other celebrations. Sometimes we make a big card all together that everyone signs their name on.

Pause for thought

|

Activity 4: Send a postcard

Using Case Study 1 as a guide, plan an activity where your students write a postcard or a very short letter to someone outside the school. See Resource 1, ‘Planning lessons’, to learn more about the value of planning ahead.

- Organise the resources you will need, and the help of any people outside the school.

- How will you introduce this activity to students?

- How will you adapt this activity if your school is not near a post office?

- If you do this activity with very young students, show interest in their mark-making and writing. Invite them to tell you what their postcard writing says.

- Did your students enjoy this activity? Were they all motivated? Did they all participate?

4 Practising writing

When young students start to write, you may see a mixture of letters, numbers, figures and shapes in their writing. Letters and numbers may not be formed correctly, but this is a developmental step and usually corrects itself over time. Note and observe students who do not seem to be making this progress. It may indicate a developmental difficulty.

Your students need plenty of writing practice in order to develop as writers. In Case Study 2, the teacher uses a number of writing routines in her classroom to achieve this.

Case Study 2: Ms Neera’s writing routines

Ms Neera teaches Class II in a government primary school.

I teach in a rural school where there is very little writing in students’ homes. I have students do some English writing practice every day. Sometimes this is a mechanical activity to develop finger control, like copying all the words in the textbook lesson that start with the letter ‘s’. Sometimes I have them combine writing and drawing, such as making a festival card or poster.

I have the students write their names and the date every day. Each week I have them write something that they would see in the real world, such as a list, a ticket or a sign. Of course, they still write stories and poems based on the textbook lessons. I let students see me writing lists, labels and reminder notes about jobs that I need to do in the classroom. It is important for them to see that writing is for communicating and for remembering.

I try not to correct them too much. I have seen from my own experience that students can become so worried about making mistakes that they become frightened to put pen to paper, and develop negative attitudes to writing.

Pause for thought

|

Video: Assessing progress and performance |

Activity 5: Multi-sensory handwriting practice

A certain amount of handwriting practice is essential for developing writing. Read through the two ‘paperless’ activities here and choose one to try out in your classroom. (Try it out with a colleague first.)

Do you need to adapt the activity for different ages or ability levels in your class? How will you do this?

‘Air Writing’

This game needs an alphabet or word list written on the board or chart paper. Students can work in a group or in the whole class.

- One student chooses a letter or a word but keeps it a secret.

- The student turns their back to the others (this is important) and writes the letter or a word in the air using arms and big gestures so that everyone can see – just as the teacher might write on the board.

- The other students guess the letter or the word – are they correct?

- They all ‘air write’ the letter or the word together, using big gestures and saying the name of each letter as they write in the air.

‘Back Writing’

This game needs an alphabet or word list written on the board or chart paper. Students sit in pairs with a small board or paper and pencil between them.

- A student chooses a letter or a word and keeps it secret.

- With a finger, they write the letter or word on a second student’s back.

- The second student writes the letter or word on paper or on the blackboard – is the second student correct?

- This activity can also be done by one student ‘writing’ a letter or word on the palm of the partner’s hand.

In the classroom, demonstrate to the students how to do your chosen activity.

As you watch students, note how the activity involves the body as well as the mind. Multi-sensory activities can help young students remember what they learn.

What do you think are the difficulties of multi-sensory activities for you as a teacher?

5 Summary

This unit has emphasised the importance of giving young students frequent opportunities to practise writing with a range of tools, in different places and for different purposes. Writing is a developmental process, starting from early mark-making to writing longer texts. It requires physical stamina as well as language knowledge.

A student’s early writing is to be enjoyed, valued and understood. It should not be an occasion for hunting and correction of errors. What young students write about, and their enthusiasm for writing, is more important than the mechanics of writing (spelling, handwriting, punctuation and spacing).

You may teach in a school where students have little or no exposure to writing in their homes or in their community. You may be the main source of writing for your students in English and Hindi. Therefore it is important to make your classroom a ‘print-rich environment’. There is a separate teacher development unit about this topic.

Other Elementary English teacher development units on this topic are:

- The learning environment.

- Developing and monitoring writing.

Resources

Resource 1: Planning lessons

Why planning and preparing are important

Good lessons have to be planned. Planning helps to make your lessons clear and well-timed, meaning that students can be active and interested. Effective planning also includes some in-built flexibility so that teachers can respond to what they find out about their students’ learning as they teach. Working on a plan for a series of lessons involves knowing the students and their prior learning, what it means to progress through the curriculum, and finding the best resources and activities to help students learn.

Planning is a continual process to help you prepare both individual lessons as well as series of lessons, each one building on the last. The stages of lesson planning are:

- being clear about what your students need in order to make progress

- deciding how you are going to teach in a way that students will understand and how to maintain flexibility to respond to what you find

- looking back on how well the lesson went and what your students have learnt in order to plan for the future.

Planning a series of lessons

When you are following a curriculum, the first part of planning is working out how best to break up subjects and topics in the curriculum into sections or chunks. You need to consider the time available as well as ways for students to make progress and build up skills and knowledge gradually. Your experience or discussions with colleagues may tell you that one topic will take up four lessons, but another topic will only take two. You may be aware that you will want to return to that learning in different ways and at different times in future lessons, when other topics are covered or the subject is extended.

In all lesson plans you will need to be clear about:

- what you want the students to learn

- how you will introduce that learning

- what students will have to do and why.

You will want to make learning active and interesting so that students feel comfortable and curious. Consider what the students will be asked to do across the series of lessons so that you build in variety and interest, but also flexibility. Plan how you can check your students’ understanding as they progress through the series of lessons. Be prepared to be flexible if some areas take longer or are grasped quickly.

Preparing individual lessons

After you have planned the series of lessons, each individual lesson will have to be planned based on the progress that students have made up to that point. You know what the students should have learnt or should be able to do at the end of the series of lessons, but you may have needed to re-cap something unexpected or move on more quickly. Therefore each individual lesson must be planned so that all your students make progress and feel successful and included.

Within the lesson plan you should make sure that there is enough time for each of the activities and that any resources are ready, such as those for practical work or active groupwork. As part of planning materials for large classes you may need to plan different questions and activities for different groups.

When you are teaching new topics, you may need to make time to practise and talk through the ideas with other teachers so that you are confident.

Think of preparing your lessons in three parts. These parts are discussed below.

1 The introduction

At the start of a lesson, explain to the students what they will learn and do, so that everyone knows what is expected of them. Get the students interested in what they are about to learn by allowing them to share what they know already.

2 The main part of the lesson

Outline the content based on what students already know. You may decide to use local resources, new information or active methods including groupwork or problem solving. Identify the resources to use and the way that you will make use of your classroom space. Using a variety of activities, resources, and timings is an important part of lesson planning. If you use various methods and activities, you will reach more students, because they will learn in different ways.

3 The end of the lesson to check on learning

Always allow time (either during or at the end of the lesson) to find out how much progress has been made. Checking does not always mean a test. Usually it will be quick and on the spot – such as planned questions or observing students presenting what they have learnt – but you must plan to be flexible and to make changes according to what you find out from the students’ responses.

A good way to end the lesson can be to return to the goals at the start and allowing time for the students to tell each other and you about their progress with that learning. Listening to the students will make sure you know what to plan for the next lesson.

Reviewing lessons

Look back over each lesson and keep a record of what you did, what your students learnt, what resources were used and how well it went so that you can make improvements or adjustments to your plans for subsequent lessons. For example, you may decide to:

- change or vary the activities

- prepare a range of open and closed questions

- have a follow-up session with students who need extra support.

Think about what you could have planned or done even better to help students learn.

Your lesson plans will inevitably change as you go through each lesson, because you cannot predict everything that will happen. Good planning will mean that you know what learning you want to happen and therefore you will be ready to respond flexibly to what you find out about your students’ actual learning.

Additional resources

- ‘Cn u rd ths? A guide to invented spelling’, GreatSchools: http://www.greatschools.org/ students/ academic-skills/ 384-invented-spelling.gs

- Teachers of India classroom resources: http://www.teachersofindia.org/ en

References

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements

Except for third party materials and otherwise stated below, this content is made available under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike licence (http://creativecommons.org/ licenses/ by-sa/ 3.0/). The material acknowledged below is Proprietary and used under licence for this project, and not subject to the Creative Commons Licence. This means that this material may only be used unadapted within the TESS-India project and not in any subsequent OER versions. This includes the use of the TESS-India, OU and UKAID logos.

Grateful acknowledgement is made to the following sources for permission to reproduce the material in this unit:

Figure 2: top left: http://theguilletots.blogspot.co.uk; top middle:courtesy of Ellen Shifrin (in Flickr); top right:http://www.childrens-mathematics.net/ gallery_pastgraphics.htm; bottom left: courtesy of http://webfronter.com/ waltham-forest/ stoneydown/ menu6/ Early_Years_Foundation_Stage/ Early_Years_Foundation_Stage_Page.html; bottom middle:http://earlyyearsmaths.e2bn.org/ library/; bottom right:http://montessoriteachings.blogspot.co.uk/.

Every effort has been made to contact copyright owners. If any have been inadvertently overlooked the publishers will be pleased to make the necessary arrangements at the first opportunity.

Video (including video stills): thanks are extended to the teacher educators, headteachers, teachers and students across India who worked with The Open University in the productions.