Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Thursday, 5 February 2026, 12:12 PM

TI-AIE: Promoting the reading environment

What this unit is about

In this unit the focus is on reading for pleasure. If students associate reading in English only with language drills and tests, they are not likely to learn much English beyond what is required. But if they learn to associate reading in English with enjoyment, they are more likely to become voluntary lifelong readers.

Your students will be learning to read in English and Hindi. The ideas and methods discussed are relevant to reading in any language. So as you read through this unit, think about how you could try out the activities for pleasurable reading in Hindi and local languages, as well as in English. Think too about how the strategies discussed would be effective with students of different abilities in your class.

What you can learn in this unit

- To promote reading for pleasure in English.

- To develop a class library.

- To be a reading role model to students.

1 Providing a reading environment

Start by thinking about actions you already take to promote reading for pleasure.

Activity 1: Motivating your students to read

Whatever level of reading skills your students might have, it is good practice to provide them with daily opportunities to experience reading pleasurably. It is important that students are motivated by a genuine desire or need to read. Here are five key actions you can take:

- Show the students that you are a reader yourself. Talk about what you like to read and share suitable examples with them.

- Create a reading environment in your classroom with a book corner.

- Make time to read aloud in class just for pleasure, not for teaching language skills and tests.

- Talk to your students about what they do and don’t like to read.

- Make time for quiet independent reading in your classroom.

Review these five points.

- Which ones do you feel you already do?

- Which ones do you feel you could do more, in your classroom?

- How much change would you need to make in order to develop these points?

- Maybe you already do these activities for reading in Hindi. How could you do these activities for English reading?

Decide which activity you will try to develop with your class over the next month. Perhaps talk to another teacher and ask them to join you in making this change in your classroom. Discussing your experiences with another teacher will help you to keep motivated and to think about the impact of your change on the learning in your classroom. The readings, case studies and activities in this unit are designed to help you get started.

In Case Study 1, a teacher tries to make some changes to encourage reading in his classroom.

Case Study 1: Mr Shankar reflects on his role

Mr Shankar teaches Class V in a government school.

In the school where I teach, students come from families with no formal schooling. I am not that confident in English, so I was sticking closely to the textbook. I am actually a keen reader, but in my own language. I like to read newspapers and magazines, and sometimes a bit of poetry. But I was not getting it across to my students about the joys of reading. My students associated reading only with testing – in English and in Hindi.

Bhaskar is one of my students. He is a very good football player and an ardent fan of David Beckham, but he has very limited reading skills. During the reading period he would do everything but read.

I thought hard about this. What could I provide that he would want to read? I got some football magazines and the sport sections of newspapers. I put them on the shelf, open. When Bhaskar saw this, he was so excited that he immediately picked up the magazine and started reading. After a few days I observed him reading the newspaper with some other students and checking out the weather. When I pointed out that they could find some English words in the magazines and in the newspapers, they began to hunt for these words.

As a teacher, I did not fully understand the critical role I could play in influencing my students’ attitude towards voluntary reading. Now I try to show my students that I am a reader. I often tell them what I have been reading at home. Sometimes this is something in the newspaper or in a magazine, or even something I saw on an advertisement or billboard. Now I try to start little conversations with students about reading and find out what they like to read.

Pause for thought

|

2 Making a book area

In Case Study 2, a teacher takes steps to improve the classroom reading environment.

Case Study 2: Mrs Shanta makes a book area

Mrs Shanta is a primary school teacher of Class V in a co-educational government school.

Most of the students in my class don’t have any books at home. Although my students had the opportunity to borrow books from the school library once a week during the library period, they were not very interested in reading.

I examined my classroom. It had very few books for my students to read. Moreover, because these few books were kept inside a cupboard, they were often not visible. I decided to try making some changes.

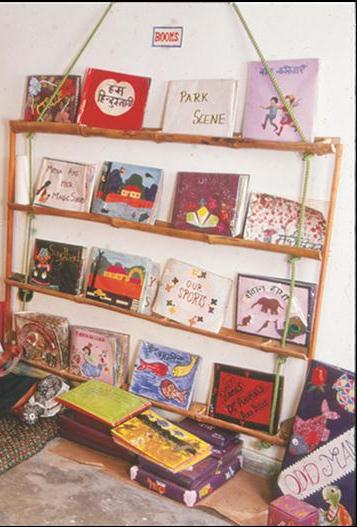

First I increased the number of books in the classroom. I asked my colleagues for any surplus books. I decided to spend all my annual allowance for purchasing teaching and learning materials on books. I bought many interesting, inexpensive books from the National Book Trust and Children’s Book Trust. With the help of my students, I also made some story books using notebooks and magazine pictures.

While selecting and making the books, I tried to make them appealing to my students. I included picture books, easy-to-read books for early readers, fables and folk tales, information books, jokes and riddle books, poetry books, comics (including Spiderman), books on sports, and books on making things. I also borrowed children’s magazines from the school library. I avoided preachy, ‘moral’ stories, since from experience I knew they put off students. However, I did take care to choose some stories that convey important messages. For example, there is a Children’s Book Trust’s publication about the problems of a tribal boy on his first few days at school due to the insensitivity of other students and the teacher, and another book about a student being bullied for stammering.

My next task was to create a ‘mini-library’ in the corner in my classroom, with shelves and a reading area. I asked my students’ advice as to where this might be. Initially they felt that the room was too small to accommodate this, but when we rearranged all the furniture we were surprised that everything could fit in.

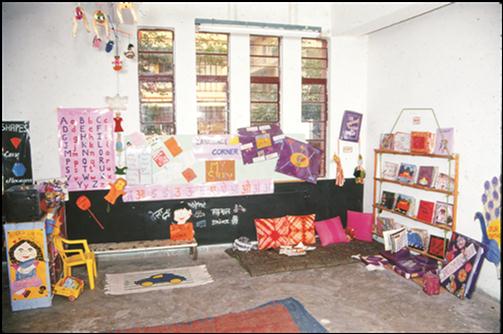

I placed a mat in the library corner because most of the students found it more comfortable to read while sitting on the floor. I obtained some attractive posters, free from book sellers, to encourage reading. A chair provided a place for me or one of the students to read aloud to the other students (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Mrs Shanta’s class library.

The students referred to the corner as a special place. The book corner gave them the message that books are so valued that space should be taken from the rest of classroom to make room for them. The students asked for more time to use the corner and permission to eat while reading the books.

Pause for thought

|

Activity 2: Look around your classroom – a planning activity

Look around your classroom and think about how you could arrange the space and furniture to make a small class library in a corner, as in Figure 2. Make a list of:

- books you can get from the local library

- books you can make

- magazines or newspapers you can get from other teachers, friends and family

- posters about books

- any other reading materials.

Figure 2 An example of a class book area.

Talk to other teachers about how you could work together to create shared resources for reading.

See Resource 1, ‘Involving all’, to learn more about developing resources for a range of interests and abilities.

3 The students’ reading

Now try the following activities.

Activity 3: Talk to your students about reading

First, do Activity 2 and make a list of books or other reading materials that you could collect in order to start a class ‘mini-library’.

In the lesson, tell your students that you want to make a book area in the classroom. Write the following questions on the board:

- What books have you read?

- Which ones did you like, and why?

- What kinds of book would you like to read?

- Are there other things you would like to read, maybe on a computer?

Divide the students into pairs and get them to ask each other the questions that you have written on the board. Give them a few minutes to do this and then bring the class back together. Ask for their answers to the questions and write their ideas on the board.

After the lesson, consolidate their ideas. Compare their ideas to your own list. Do their ideas match yours?

What did you find out?

How can this kind of information help you tailor the support you can give to individual students as readers?

Over the next few weeks, assemble your small selection of reading materials.

Will you have rules for the ‘library’? Will you tell parents about the library? Could you ask them to help? Perhaps you could ask your students to plan a small ceremony for the opening of your book area.

You can use a reading corner in a variety of ways. By choosing a range of reading materials you can cater to diverse tastes and needs of students. For example, a gifted student may find it interesting to read challenging texts that she otherwise may not have access to. Similarly, being able to read texts suited to their reading levels will build up the confidence of students who have reading problems. With the help of colleagues and older students you could also prepare worksheets to supplement their reading.

A reading corner will also help you with classroom management. If you have a large class or teach a multigrade class, one group can be assigned independent reading at the corner while you work with others, and vice versa. Of course it will take some time for students to work independently in a disciplined manner if they are not used to it. But with firm rules and initial guidance, they can be taught to do so.

Video: Involving all |

The next activity is about reading aloud.

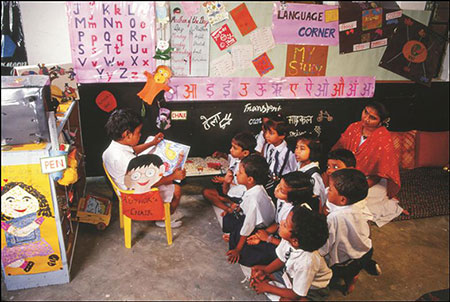

You will know how much students love to imitate their teacher. What you do and say, they will do and say. When you read aloud, you are a model for the enjoyment of reading. Reading aloud, and having students read aloud, will help you and your students improve your pronunciation of English.

Activity 4: Reading aloud with expression

Choose a short story or a poem in English that you know well and that you think your students will enjoy. It does not need to be from the textbook. Read the story or the poem aloud to the class.

Then invite a student to read the story to the rest of the class (Figure 3). Let the student hold the book and pretend to be the teacher. The student may have memorised some or all of the text, but this is fine – let the student imitate the way you read with expression and enthusiasm. Sit with the other students and show them how to be a good listener. Join in if there are choral parts to the reading.

Figure 3 A student reads a story to other students and the teacher.

You must avoid attaching any language drills to this reading aloud activity. Simply focus on the pleasure and enjoyment of reading.

When you let students read aloud to the class, with you in the audience, you can observe reading skills and behaviours. Do students handle books carefully? Are they reading or repeating from memory, or a bit of both? Are the other students listening and responding?

4 Creating books of the students’ words and pictures

Now try the following activity.

Activity 5: Creating books of students’ words and pictures

This activity is suitable for Classes I–IV, but you can adapt it for older classes.

Create books using students’ own words. If you have a large class, you can make a big book over several days or a week. Alternatively, you can make a book for each student.

- You will need magazine pictures to cut out or the students’ own drawings, as well as paste, paper and pens.

- Tell the students they are going to make a book in English.

- Ask students to think about their favourite word in Hindi or their home language. They can share their word with a friend. Ask them to draw a picture of their word, or cut out a picture from a magazine and paste it onto a piece of paper.

- Write their favourite words in Hindi and in English on the board. Practise saying the words in English together, referring to the drawings or pictures.

- Ask the students to write the word in English next to their picture of the word. For students who are not yet able to form letters, write the word for them.

- Take the students’ individual papers and create a book with the title ‘We Can Read!’ Each page of the book should have a different word, with an illustration or a pasted-in picture, for each student. On every page you write a caption in English for each student that says, for example:

- Mehak can read ‘ice cream’.

- Susheela can read ‘festival’.

- Munir can read ‘car’.

- Deepti can read ‘computer’.

Read the books and practise English together. Invite parents into the classroom so that students can read the book to their mothers and fathers. Continue to build your class library and develop the reading environment.

You can adapt this activity by:

- making a collection of ‘I Can Read’ books on different topics such as food, transport, plants, family or parts of the body

- changing the writing to practise different sentence structures in English; for example, the title of the book could be ‘What Do You Like to Eat?’ with pages that say ‘Munir likes to eat rice’, ‘Deepti likes to eat mango’, etc.

Pause for thought

|

5 Summary

This unit has focused on how you can develop a positive reading environment in your classroom.

Reading in any language has a crucial role to play in creating independent learners and increasing their educational attainment. Reading is the basis of a student‘s success at all levels of education. Developing good reading habits is vital to a child’s future – not just academically, but in everyday life as well. Students with good reading habits learn more about the world around them and develop an interest in language and in other cultures. Reading leads to asking questions and seeking answers, which expands students’ knowledge on a constant basis.

Other Elementary English teacher development units on this topic are:

- Letters and sounds of English

- Storytelling

- Shared reading

- Planning around a text

- Developing and monitoring reading.

Resources

Resource 1: Involving all

What does it mean to ‘involve all’?

The diversity in culture and in society is reflected in the classroom. Students have different languages, interests and abilities. Students come from different social and economic backgrounds. We cannot ignore these differences; indeed, we should celebrate them, as they can become a vehicle for learning more about each other and the world beyond our own experience. All students have the right to an education and the opportunity to learn regardless of their status, ability and background, and this is recognised in Indian law and the international rights of the child. In his first speech to the nation in 2014, Prime Minister Modi emphasised the importance of valuing all citizens in India regardless of their caste, gender or income. Schools and teachers have a very important role in this respect.

We all have prejudices and views about others that we may not have recognised or addressed. As a teacher, you carry the power to influence every student’s experience of education in a positive or negative way. Whether knowingly or not, your underlying prejudices and views will affect how equally your students learn. You can take steps to guard against unequal treatment of your students.

Three key principles to ensure you involve all in learning

- Noticing: Effective teachers are observant, perceptive and sensitive; they notice changes in their students. If you are observant, you will notice when a student does something well, when they need help and how they relate to others. You may also perceive changes in your students, which might reflect changes in their home circumstances or other issues. Involving all requires that you notice your students on a daily basis, paying particular attention to students who may feel marginalised or unable to participate.

- Focus on self-esteem: Good citizens are ones who are comfortable with who they are. They have self-esteem, know their own strengths and weaknesses, and have the ability to form positive relationships with other people, regardless of background. They respect themselves and they respect others. As a teacher, you can have a significant impact on a young person’s self-esteem; be aware of that power and use it to build the self-esteem of every student.

- Flexibility: If something is not working in your classroom for specific students, groups or individuals, be prepared to change your plans or stop an activity. Being flexible will enable you make adjustments so that you involve all students more effectively.

Approaches you can use all the time

- Modelling good behaviour: Be an example to your students by treating them all well, regardless of ethnic group, religion or gender. Treat all students with respect and make it clear through your teaching that you value all students equally. Talk to them all respectfully, take account of their opinions when appropriate and encourage them to take responsibility for the classroom by taking on tasks that will benefit everyone.

- High expectations: Ability is not fixed; all students can learn and progress if supported appropriately. If a student is finding it difficult to understand the work you are doing in class, then do not assume that they cannot ever understand. Your role as the teacher is to work out how best to help each student learn. If you have high expectations of everyone in your class, your students are more likely to assume that they will learn if they persevere. High expectations should also apply to behaviour. Make sure the expectations are clear and that students treat each other with respect.

- Build variety into your teaching: Students learn in different ways. Some students like to write; others prefer to draw mind maps or pictures to represent their ideas. Some students are good listeners; some learn best when they get the opportunity to talk about their ideas. You cannot suit all the students all the time, but you can build variety into your teaching and offer students a choice about some of the learning activities that they undertake.

- Relate the learning to everyday life: For some students, what you are asking them to learn appears to be irrelevant to their everyday lives. You can address this by making sure that whenever possible, you relate the learning to a context that is relevant to them and that you draw on examples from their own experience.

- Use of language: Think carefully about the language you use. Use positive language and praise, and do not ridicule students. Always comment on their behaviour and not on them. ‘You are annoying me today’ is very personal and can be better expressed as ‘I am finding your behaviour annoying today. Is there any reason you are finding it difficult to concentrate?’,which is much more helpful.

- Challenge stereotypes: Find and use resources that show girls in non-stereotypical roles or invite female role models to visit the school, such as scientists. Try to be aware of your own gender stereotyping; you may know that girls play sports and that boys are caring, but often we express this differently, mainly because that is the way we are used to talking in society.

- Create a safe, welcoming learning environment: All students need to feel safe and welcome at school. You are in a position to make your students feel welcome by encouraging mutually respectful and friendly behaviour from everyone. Think about how the school and classroom might appear and feel like to different students. Think about where they should be asked to sit and make sure that any students with visual or hearing impairments, or physical disabilities, sit where they can access the lesson. Check that those who are shy or easily distracted are where you can easily include them.

Specific teaching approaches

There are several specific approaches that will help you to involve all students. These are described in more detail in other key resources, but a brief introduction is given here:

- Questioning:If you invite students to put their hands up, the same people tend to answer. There are other ways to involve more students in thinking about the answers and responding to questions. You can direct questions to specific people. Tell the class you will decide who answers, then ask people at the back and sides of the room, rather than those sitting at the front. Give students ‘thinking time’ and invite contributions from specific people. Use pair or groupwork to build confidence so that you can involve everyone in whole-class discussions.

- Assessment:Develop a range of techniques for formative assessment that will help you to know each student well. You need to be creative to uncover hidden talents and shortfalls. Formative assessment will give you accurate information rather than assumptions that can easily be drawn from generalised views about certain students and their abilities. You will then be in a good position to respond to their individual needs.

- Groupwork and pair work:Think carefully about how to divide your class into groups or how to make up pairs, taking account of the goal to include all and encourage students to value each other. Ensure that all students have the opportunity to learn from each other and build their confidence in what they know. Some students will have the confidence to express their ideas and ask questions in a small group, but not in front of the whole class.

- Differentiation:Setting different tasks for different groups will help students start from where they are and move forward. Setting open-ended tasks will give all students the opportunity to succeed. Offering students a choice of task helps them to feel ownership of their work and to take responsibility for their own learning. Taking account of individual learning needs is difficult, especially in a large class, but by using a variety of tasks and activities it can be done.

Additional resources

- Children’s Book Trust India: http://www.childrensbooktrust.com/

- Karadi Tales: http://www.karaditales.com/

- National Book Trust India: http://www.nbtindia.gov.in/

- NCERT textbooks: http://www.ncert.nic.in/ NCERTS/ textbook/ textbook.htm

- Teachers of India classroom resources: http://www.teachersofindia.org/ en

References

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements

Except for third party materials and otherwise stated below, this content is made available under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike licence (http://creativecommons.org/ licenses/ by-sa/ 3.0/). The material acknowledged below is Proprietary and used under licence for this project, and not subject to the Creative Commons Licence. This means that this material may only be used unadapted within the TESS-India project and not in any subsequent OER versions. This includes the use of the TESS-India, OU and UKAID logos.

Grateful acknowledgement is made to the following sources for permission to reproduce the material in this unit:

Images are courtesy of Suman Bhatia.

Every effort has been made to contact copyright owners. If any have been inadvertently overlooked the publishers will be pleased to make the necessary arrangements at the first opportunity.

Video (including video stills): thanks are extended to the teacher educators, headteachers, teachers and students across India who worked with The Open University in the productions.