Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Thursday, 5 February 2026, 9:24 AM

TI-AIE: Storytelling

What this unit is about

The aim of this unit is to develop your skills in using English for storytelling.

Storytelling can be a powerful teaching method because you, the teacher, are in direct communication with your students. Stories and storytelling require only one resource – you.

Storytelling allows you to ask open questions, such as ‘What do you think will happen next?’ and ‘Why do you think he does this?’, that encourage students to think, recall, reflect, imagine and respond. All of these develop their language skills. Experienced teachers know that students will remember language very well, and try to use it, when they hear it in a story.

It is good practice to tell and read stories regularly in the classroom because these are learning opportunities as well as fun occasions. In India we are fortunate to have many stories from folklore and tradition that teachers can use to promote language learning. When you tell stories in your classroom it will be natural and expected to mix local languages and English, especially in the early years of school.

What you can learn in this unit

- To use bilingual storytelling methods.

- To select stories in English to use with your students.

- To practise storytelling in English.

1 Learning new words

Start by reading a story in two languages, in an activity for you.

Activity 1: Learning new words

Read the short story below.

There was a man and he seemed very upset. This andras, this man, he went to the kipo behind his house (‘kipo’ is a garden) looking for something. The andras got down on his hands and knees and started scratching underneath the traiandafila, the roses.

Now the wife of the andra, his yineka, was upstairs in the house. The yineka looked out through the bedroom parathiro and saw her andra searching for something under the traiandafila.

She asked him what he was doing. ‘I’m looking for my house keys,’ her andras shouted.

‘Did you lose your house klidia down there in the kipo, under the traiandafila?’

‘No,’ said her andras. ‘I didn’t lose my klidia here under the traiandafila, but the light is so much better here!’

Pause for thought In this example, the Greek words are explained in different ways – what are these different ways? How did you make sense of the words that are not explained in the story: ‘parathiro’ and ‘klidia’? As you read this story, you were learning some new words in Greek: ‘man’, ‘garden’, ‘roses’ and ‘wife’. You probably did not struggle to understand the meaning of the Greek words although you have probably never used the language before, because nearly all the words were briefly explained and then immediately used in a familiar context within a simple and entertaining story. You can teach students English in the same way, adapting a story in any language to introduce English words and phrases. |

Activity 2: Learning new English words

Take a very short story or poem that you and your students know well in Hindi. Choose a few English words you could introduce in the story or poem.

Decide how you will introduce the English words. Will you translate them, or explain them in some other way?

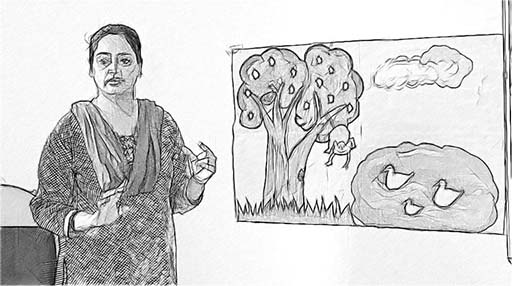

You could use pictures to help the students identify and learn the words in English (Figure 1).

Try out your bilingual story or poem with a colleague. Listen to their feedback and make any changes that will improve the use of English words in the story.

Then try it out with your class. Do they understand the English words? Do they enjoy the story?

2 Using simple stories

Introducing a small number of English words will help your students to develop confidence in using English. In the case study that comes next, the teacher tells a whole story to her class in English. As you read, think about the benefits and potential risks of this method.

Case Study 1: Amina tells a familiar story in English

Amina is a student teacher in a rural school in Maharashtra, where there were no English signboards or newspapers in the community, and no one spoke English.

I took the story of ‘The Thirsty Crow’ from the language textbook. I knew it very well, and so did my students. I wrote out a very simple version of the story in English. I practised telling this simple version of the story aloud to my husband at home. I practised until I felt very confident to tell the English version to my students. I made up some gestures to go with my storytelling.

I told students in Class I the story, using actions and gestures and my voice to convey as much of my meaning as possible. They knew this story very well already, but only in Marathi.

The students sat through my story without saying anything or showing any feeling. I was sure that they had not understood anything. At the end I asked the students in Marathi: ‘What story did I tell?’ To my surprise, the students were able to identify the story quite well, and they then began to tell the story in their own words in Marathi!

I realised that the students had not understood all the English words that had been spoken, but were able to make a number of good guesses. Because I used actions and gestures, they knew that I was telling a story and they guessed that it was a story they knew. I wrote on the board the key English words from the story: ‘crow’, ‘drink’, ‘water’, ‘stones’, ‘pot’ and ‘thirsty’. I read the words out and the students repeated them after me. I let them draw pictures for these words and label them.

Now, before I tell a story in English, I speak and write out the key words on the board. Sometimes I also prepare pictures or for a story (Figure 2).

I realise my method takes some time to organise and prepare. But I have found that it is worthwhile, not just for students. My own English confidence is slowly improving. Also, storytelling has helped my management of the classroom.

Pause for thought Amina realised that her students could understand a lot more English than she thought. Do you think this is true for your students? How would you find out? |

Activity 3: Practising a story

Read the short story in English. Read it more than once. Underline or circle any words you are not sure of, and look these up in a dictionary. Read it aloud to yourself, or to someone in your family.

‘The Moon and His Two Wives’

Did you know that the Moon has two wives?

One is an excellent cook. When the Moon visits her, she makes him many, many delicious plates of food. She cooks and he eats. She cooks and he eats. She cooks and he eats. And he gets fatter and fatter until he is entirely round and he can’t eat any more.

When he can’t eat any more, he goes off to see his other wife. She is an excellent storyteller. And when he visits her she tells him many, many exciting stories. Day and night, night and day, he sits and listens. And he is so busy listening that he forgets to eat. So he gets thinner and thinner until he is just a tiny crescent.

Then he gets hungry, and so he goes to see his cook-wife again.

After you have read the story several times, try to tell it aloud without looking at the text.

Can you put any gestures to some of the words? Try telling the story, without reading it, to someone else at school or at home.

Pause for thought What does this story teach about language and about the natural world? |

This very short story introduces some interesting vocabulary such as ‘excellent’, ‘delicious’ and ‘exciting’. It also introduces an astronomical term: crescent. It introduces the opposite words: fat and thin. The story has repeating phrases such as ‘day and night, night and day’, ‘fatter and fatter’, and ‘thinner and thinner’. You can use these ideas as starting points to explore language. For example, you can think of other opposite words such as ‘bigger’ and ‘smaller’. You can think of words that have the same meaning, such as ‘excellent’, ‘outstanding’ or ‘first-rate’.

Traditional stories often have gender stereotypes, such as the husband and wife roles in ‘The Moon and His Two Wives’. How would you talk to students about this? Think of ways to make the story less stereotypical. For example, the moon could cook for his wife and eat so much of his own food that he becomes fat. Or the moon could have two friends instead of two wives.

Of course, there is a scientific explanation for why the moon changes shape. Do you think the story ‘The Moon and His Two Wives’ could cause students to develop misconceptions? Would you introduce the astronomical concepts at the same time as you tell this story? You can talk to students about the differences between the scientific way of explaining the world and the folk story way of explaining what we see around us. You can also use this opportunity to ask the students if they have different versions of this story in their communities, or tell them to narrate stories they have heard from their community that seek to explain the natural world. Encourage them to use English words while narrating.

Think of other traditional stories that you know. Do they have interesting words and patterns of language? Do they present problems of stereotyping and scientific misconceptions?

3 Storytelling in the classroom

Now try this activity.

Activity 4: Tell a story in simple English

Choose a very short story your students already know well. It could be a story everyone knows from life, or from the textbook. It is helpful if the story has a repeating word or phrase, as this gives you and students more opportunities to practice.

Prepare a very simple English version of this story. Before you tell the story to students, practise it at home, or practise with a fellow teacher.

You can use word cards for key vocabulary in the story, or write these words on the blackboard.

Now read the lesson plan in Resource 1. Adapt it to suit your classroom, the needs of your students and your own professional development.

With students, tell the story slowly. Use pictures or gestures to mime the story as you speak. Let students guess at the meaning of your words.

After you tell the story, let the students practise telling it themselves. If there are students with hearing problems in your class, let other students mime the story to them.

Let the session be enjoyable. You do not need to attach any language drills or writing practise to the storytelling.

After a storytelling session, make brief notes about individual students, using criteria such as:

- listens carefully

- shows involvement (comments, asks questions)

- is able to use some English words and phrases in a story

- is able to tell a story partly in English

- is able to tell a story in English.

You can do this for small groups of students throughout the year.

Activity 5: Preparing for storytelling in the classroom

To gather the class together and prepare students to listen to a story, you can ring a story time bell or beat a story time drum. You can say a rhyme or sing a version of ‘If You’re Happy and You Know It’:

If you want to hear a story, clap your hands!

If you want to hear a story, clap your hands!

If you want to hear a story, if you want to hear a story,

If you want to hear a story, clap your hands!

Practise and use these English phrases for storytelling in your classroom:

- ‘It’s story time!’

- ‘Sit down, everyone.’

- ‘Are you ready?’

- ‘Is everyone ready to listen?’

- ‘Are you ready to listen?’

- ‘Listen to me.’

- ‘Who is listening?’

- ‘Repeat after me …’

- ‘Say it with me …’

- ‘Let’s say together …’/‘Say it with me …’

- ‘Now you say it.’

- ‘You are good listeners!’

- ‘You are good storytellers!’

If you set in place such routines, managing a large class and/or multigrade class for storytelling becomes easier, and students can join in and practise English with you.

See Resource 2, ‘Storytelling, songs, role play and drama’, to learn more about extending the potential of stories in your classroom.

Video: Storytelling, songs, role play and drama |

4 Summary

In this unit the focus has been on learning and using English through storytelling with the students in your class. Through stories, we can start to use a new language in a familiar context.

In the classroom, storytelling and reading stories aloud are key elements of language teaching. Creating, recalling and repeating stories are a learning process for teachers as well as for students. The ability to tell a story in an interesting and lively way is an important teaching skill. A good story is entertaining, of course, but it can also hold students’ attention while they learn important concepts, attitudes and language skills. Telling and listening to stories is a pleasurable activity that can bring teachers and students together in a shared experience.

Other Elementary English teacher development units on this topic are:

- Songs, rhymes and word play

- Shared reading

- Planning around a text

- Developing and monitoring reading

- Promoting the reading environment.

Resources

Resource 1: Lesson plan for storytelling

Adapt this plan for your own class.

Here are some issues to consider as you choose a story and plan to tell it.

Choose a story you know well and that your students know well in Hindi or their local language. It can be from a book, but you will need to tell it aloud without the book. The story might be linked to a topic in your textbook, or it might be linked to a local festival or community event. The story might be important to students’ experiences in a general way, or it might develop their knowledge in a specific subject area such as science, history or geography. Perhaps the story has a moral message that you feel is important for students to learn. Perhaps you will choose a traditional tale. Why is this story a good one for your class?

- Consider the story in terms of its length. Can it be told in a short space of time?

- Consider the story in terms of complexity. Does it use familiar or unfamiliar words and phrases?

- Where in the story will you be able to stop and invite students to join in with you or repeat after you?

- Consider whether the story is inclusive from the perspective of marginalised groups. Will any student feel left out or embarrassed by the story?

- Think about what props or pictures you have or you need to make, to help the story come alive for the students. Will you need, for instance, pictures of a hat, a broom or a lamp? Or will you use real objects?

Preparation

- Choose a story you know well.

- Prepare a simple version of the story in English.

- Practise telling it, so that you are confident.

- Select key words and phrases. Choose words and phrases that are important to the story and are repeated in the story, so that students have more than one opportunity to listen and practise them. Make these words and phrases memorable and manageable, so that students will enjoy learning them.

- Write the key words and phrases in English on word cards.

- Make pictures (draw them or cut them out of a magazine) to match the word cards. Or use objects, such as a hat, broom or pot.

- Practise telling the story using the word cards and pictures or objects.

- Find moments in the story where you can stop and ask students to repeat after you, or to join in a repeating phrase.

- Decide how you will prepare the students to listen to the story (rhyme, song, drum, bell or other method).

In the lesson

- Prepare the students for a story so that they are all listening (ring a bell, beat a drum, clap).

- Tell them they will hear a story in English and practise English together with you.

- Tell the story. Speak slowly. Use gestures and facial expressions. Show the word cards, pictures or objects. Encourage students to repeat and join in.

- Practise together the repeating words or phrases in English, matching words with pictures or objects.

After the story

- Keep the English words and phrases on the wall so that students can continue to read and practise them.

- Encourage the students to retell the story in English.

- When you tell the story again, ask the students questions such as ‘Now, what happened next?’, ‘Where did that happen?’ or ‘Who did that?’ Take this as an opportunity to assess students’ understanding.

Resource 2: Storytelling, songs, role play and drama

Students learn best when they are actively engaged in the learning experience. Your students can deepen their understanding of a topic by interacting with others and sharing their ideas. Storytelling, songs, role play and drama are some of the methods that can be used across a range of curriculum areas, including maths and science.

Storytelling

Stories help us make sense of our lives. Many traditional stories have been passed down from generation to generation. They were told to us when we were young and explain some of the rules and values of the society that we were born into.

Stories are a very powerful medium in the classroom: they can:

- be entertaining, exciting and stimulating

- take us from everyday life into fantasy worlds

- be challenging

- stimulate thinking about new ideas

- help explore feelings

- help to think through problems in a context that is detached from reality and therefore less threatening.

When you tell stories, be sure to make eye contact with students. They will enjoy it if you use different voices for different characters and vary the volume and tone of your voice by whispering or shouting at appropriate times, for example. Practise the key events of the story so that you can tell it orally, without a book, in your own words. You can bring in props such as objects or clothes to bring the story to life in the classroom. When you introduce a story, be sure to explain its purpose and alert students to what they might learn. You may need to introduce key vocabulary or alert them to the concepts that underpin the story. You may also consider bringing a traditional storyteller into school, but remember to ensure that what is to be learnt is clear to both the storyteller and the students.

Storytelling can prompt a number of student activities beyond listening. Students can be asked to note down all the colours mentioned in the story, draw pictures, recall key events, generate dialogue or change the ending. They can be divided into groups and given pictures or props to retell the story from another perspective. By analysing a story, students can be asked to identify fact from fiction, debate scientific explanations for phenomena or solve mathematical problems.

Asking the students to devise their own stories is a very powerful tool. If you give them structure, content and language to work within, the students can tell their own stories, even about quite difficult ideas in maths and science. In effect they are playing with ideas, exploring meaning and making the abstract understandable through the metaphor of their stories.

Songs

The use of songs and music in the classroom may allow different students to contribute, succeed and excel. Singing together has a bonding effect and can help to make all students feel included because individual performance is not in focus. The rhyme and rhythm in songs makes them easy to remember and helps language and speech development.

You may not be a confident singer yourself, but you are sure to have good singers in the class that you can call on to help you. You can use movement and gestures to enliven the song and help to convey meaning. You can use songs you know and change the words to fit your purpose. Songs are also a useful way to memorise and retain information – even formulas and lists can be put into a song or poem format. Your students might be quite inventive at generating songs or chants for revision purposes.

Role play

Role play is when students have a role to play and, during a small scenario, they speak and act in that role, adopting the behaviours and motives of the character they are playing. No script is provided but it is important that students are given enough information by the teacher to be able to assume the role. The students enacting the roles should also be encouraged to express their thoughts and feelings spontaneously.

Role play has a number of advantages, because it:

- explores real-life situations to develop understandings of other people’s feelings

- promotes development of decision making skills

- actively engages students in learning and enables all students to make a contribution

- promotes a higher level of thinking.

Role play can help younger students develop confidence to speak in different social situations, for example, pretending to shop in a store, provide tourists with directions to a local monument or purchase a ticket. You can set up simple scenes with a few props and signs, such as ‘Café’, ‘Doctor’s Surgery’ or ‘Garage’. Ask your students, ‘Who works here?’, ‘What do they say?’ and ‘What do we ask them?’, and encourage them to interact in role these areas, observing their language use.

Role play can develop older students’ life skills. For example, in class, you may be exploring how to resolve conflict. Rather than use an actual incident from your school or your community, you can describe a similar but detached scenario that exposes the same issues. Assign students to roles or ask them to choose one for themselves. You may give them planning time or just ask them to role play immediately. The role play can be performed to the class, or students could work in small groups so that no group is being watched. Note that the purpose of this activity is the experience of role playing and what it exposes; you are not looking for polished performances or Bollywood actor awards.

It is also possible to use role play in science and maths. Students can model the behaviours of atoms, taking on characteristics of particles in their interactions with each other or changing their behaviours to show the impact of heat or light. In maths, students can role play angles and shapes to discover their qualities and combinations.

Drama

Using drama in the classroom is a good strategy to motivate most students. Drama develops skills and confidence, and can also be used to assess what your students understand about a topic. A drama about students’ understanding of how the brain works could use pretend telephones to show how messages go from the brain to the ears, eyes, nose, hands and mouth, and back again. Or a short, fun drama on the terrible consequences of forgetting how to subtract numbers could fix the correct methods in young students’ minds.

Drama often builds towards a performance to the rest of the class, the school or to the parents and the local community. This goal will give students something to work towards and motivate them. The whole class should be involved in the creative process of producing a drama. It is important that differences in confidence levels are considered. Not everyone has to be an actor; students can contribute in other ways (organising, costumes, props, stage hands) that may relate more closely to their talents and personality.

It is important to consider why you are using drama to help your students learn. Is it to develop language (e.g. asking and answering questions), subject knowledge (e.g. environmental impact of mining), or to build specific skills (e.g. team work)? Be careful not to let the learning purpose of drama be lost in the goal of the performance.

Additional resources

- Karadi Tales: http://www.karaditales.com/

- National Book Trust India: http://www.nbtindia.gov.in/

- NCERT textbooks: http://www.ncert.nic.in/ NCERTS/ textbook/ textbook.htm

- Teachers of India classroom resources: http://www.teachersofindia.org/ en

References

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements

This content is made available under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike licence (http://creativecommons.org/ licenses/ by-sa/ 3.0/), unless identified otherwise. The licence excludes the use of the TESS-India, OU and UKAID logos, which may only be used unadapted within the TESS-India project.

Every effort has been made to contact copyright owners. If any have been inadvertently overlooked the publishers will be pleased to make the necessary arrangements at the first opportunity.

Video (including video stills): thanks are extended to the teacher educators, headteachers, teachers and students across India who worked with The Open University in the productions.