Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Thursday, 13 November 2025, 5:40 PM

TI-AIE: Developing and monitoring reading

What this unit is about

This unit is about resources and practices to help your students develop the key skills of reading aloud and reading silently in English, and the transition from reading aloud to silent reading.

When you listen to your students read aloud in English, you can monitor their reading ability. Reading aloud allows students to practise their pronunciation and develop confidence in using English.

Reading silently is quite an advanced skill for students, whether they are reading in their first or second language. It normally develops after they have been read aloud to, and then from reading aloud alongside someone else. Reading silently is therefore a goal to work towards as students become more mature and independent readers.

This unit will introduce you to the practice of organising students for guided reading in ability groups. This may be a new idea to you, or you may already be doing aspects of guided reading. You will look at reading cards as a resource to encourage and monitor reading.

What you can learn in this unit

- To develop reading aloud in English with your students.

- To develop your students’ silent reading in English.

- To organise guided reading in English.

1 Developing reading aloud in English with your students

Start by thinking about what you do now to develop your students as readers in English.

Activity 1: Audit your reading routines

It’s not only important for you to read aloud in English to your class – your students should have opportunities to do this as well.

Think about your own classes. How often do you do the following activities – never, occasionally or often?

| Activity | Never | Occasionally | Often |

|---|---|---|---|

| I read aloud from the textbook or the board. The students silently follow along with me. | |||

| I read aloud from the textbook or the board. The students repeat immediately after me. | |||

| I read aloud from the textbook or the board. The students read aloud along with me. | |||

| I listen to students read aloud in small groups, by ability, while the rest of the class is working quietly. | |||

| I call on students read aloud and the whole class listens. | |||

| I ask students to read a text silently and I observe them. | |||

| I ask students to read a text silently and I ask them questions about it. |

All these are effective methods and it is good practice to vary them in your classroom reading routines. But the more exposure that students have to spoken English, the better. So it is very good practice to read aloud and to have students read aloud – along with you, immediately after you or with you just listening to them. In each of these instances, you can observe and assess students’ reading skills.

What are the routines you use most often? What are the benefits of these routines for you as a teacher and for the students as learners of English?

Now look at the routines you don’t use, or use very little. What are the challenges for you, as a teacher, in implementing these practices? Is it a matter of confidence, resources or class size? The activities and resources in this unit aim to develop your confidence to widen your reading routines in the classroom.

2 Getting your students to read aloud

In the case study that follows, a teacher takes steps to monitor and evaluate students’ reading.

Case Study 1: Mr Govinder encourages students to read aloud

Mr Govinder is a Class V English teacher.

Our English textbooks have lots of short stories in them. I used to always read these stories aloud to my students and have them silently follow the stories in the book as I read. Sometimes, though, I noticed that they could not follow the story or had no idea what the text was about when I asked them questions about it.

I wanted to monitor whether or not they could understand what they were reading. One way to do this, I thought, was to have the students read aloud from the textbook, particularly after we had all read the story once together. I could only call on three or four students per day, but I thought that if I did this every day, most students could have at least one turn every two weeks. In this way, they would have regular opportunities to read aloud and hear each other read aloud.

I used to think that if I had taught my students well, they would not make mistakes while reading aloud. But I noticed that the students who read without mistakes were actually just pretending to read, reciting the text from memory. And I realised that if they were just memorising what I had read to them, they weren’t actually learning anything. The students who were really reading and understanding tended to read a lot slower, made mistakes and had difficulty reading some words. I realised that those ‘mistakes’ actually showed that learning was taking place.

But students don’t like to make mistakes, so I have to encourage them to keep trying and praising them regularly while they were reading.

Sometimes when a student comes across a word that is hard for them to read, they may be tempted to skip over it. But I try to encourage them to take a bit of time to look at the word and understand what it means. Once they have read and understood the word, I ask the student to go back to the beginning of the sentence and read it again. Repeated readings of difficult words and phrases seem to result in improvements in the students’ speed, accuracy and expressiveness when they read aloud. That’s why it’s important that students get to read texts that are interesting, so that they feel motivated to read them again and again.

However, I find that if a student is stumbling repeatedly when reading something, there is no point in having them continue with it. So I make a note to myself that the student needs further support with reading and I choose a simpler text for them to read the next time. I then work with them in a one-to-one session when I can. I’ve noticed that students’ reading abilities are most likely to improve if they are given texts where they are familiar with the majority of words and phrases.

Pause for thought

|

In the next activity, the focus is on developing your students’ skills in reading aloud in English.

Activity 2: Listen to students read aloud

Plan a 30-minute session where you listen to individual students read aloud to you in English.

- Select a small group of students (no more than six) who are of a similar ability.

- Choose a section of the textbook for them to read – they should not be overly familiar with it.

- Make sure that each student has a copy of the textbook or that they all can see the text.

- Set the rest of the class some quiet work.

- Organise a space in the classroom where you can sit with the group.

- Establish a rule that you and the group cannot be disturbed.

- Tell the class that everyone will have an opportunity to read to you in a small group.

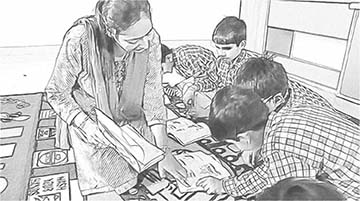

Listening to students reading aloud.

Sit with the small group. Explain that each student will read a passage aloud to you so that you can hear and encourage their reading. Give the six students the textbook and have them read a section aloud to you, one after another.

Spending time with a small group.

As your students read, listen carefully to them. If they are unsure of a word, do not jump in to help them straight away. Encourage them gently to try to work out the word or sentence. Which of the following strategies do you see them use?

- Sounding words (using letter/sound knowledge)

- Predicting words from the context of the story or any associated pictures

- Predicting what words come next because of familiar phrasing

- Reading one word at a time

- Reading connected text and phrases

- Pointing to each word

- Reading words from memory

- Reading sentences from memory

- Making guesses.

All of these are acceptable ways to practise reading in a new language. If students are using one strategy, you can encourage them to try other ways of working out words. You can ask, for example, ‘What does the picture show?’ or ‘What letter is this and what sound does it make?’

Listening to students read aloud is an assessment opportunity. How do you decide what book or text the student should read next? How important are reading levels in your decision? Do you take the student’s age into account? What other factors influence your assessments?

When you listen to students read aloud, you can monitor their fluency and pronunciation. You can ask them comprehension questions. You can also ask the students what they like about the book, or what they find interesting or funny. This gives them time to talk about reading in an enjoyable way.

If you listen to a group of students read to you every week, then you will be able to hear every student in your class read aloud over a month to six weeks. Organise a wall chart to show which group will read with you each week. Make this a special time for you and each group of students.

See Resource 1, ‘Monitoring and giving feedback’ to learn more about the methods to evaluate and record student progress.

3 Resources for reading silently

Students should be given opportunities to read silently in class. This is most likely to be the kind of reading they will do in real life. To prepare your students to read on their own, you can use ‘reading cards’: small booklets or cards with short texts or stories that are graded according to difficulty. You can prepare your own grade cards by copying out simple texts or stories from English textbooks of different types. You can either write out some of the questions given as part of the exercise in the textbook, or make your own questions.

Activity 3: Exploring reading cards for silent reading

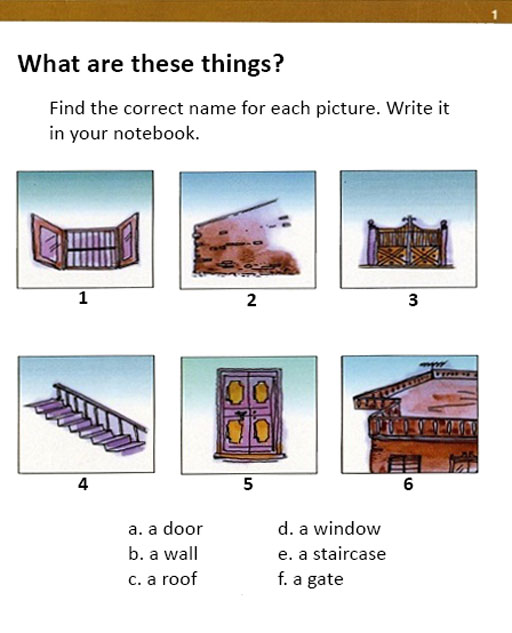

Figure 1 shows an example of a word reading card for the beginner. Each card has pictures for a group of words that have related meanings, and the same instructions. To begin with, you can explain the instructions to your students in their language.

Figure 1 An example of a reading card.

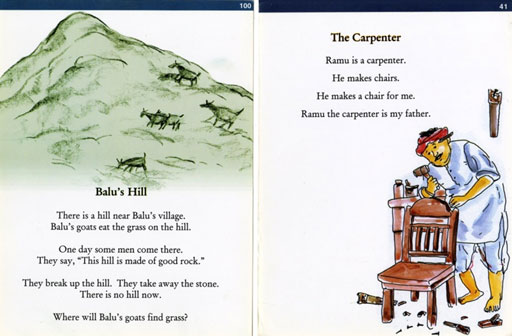

Figure 2 shows two more reading cards, this time with short stories.

On the back of each card are some questions, listed below. Do you think they are easy or difficult? Which class should a student be in to be able to read these cards and answer the questions by themselves?

‘Balu’s Hill’

Choose the right words:

- Balu’s village is near a ______ (hill, river).

- Balu has some ______ (dogs, goats).

- The goats eat ______ (stone, grass).

- The hill is made of ______ (rock, grass).

- The men take away the ______ (grass, stone).

‘The Carpenter’

Choose the right words:

- Ramu is a ______ (farmer, carpenter).

- Ramu makes ______ (cars, chairs).

- Ramu makes a ______ (chair, table) for me.

- Ramu is my ______ (mother, father).

Do you have experience of using reading cards? If so, what do you think are the benefits and problems of students using them?

Do you have reading cards available to you, but have not ever used them in the classroom? What has prevented you from using them?

Do you think you could make your own reading cards, perhaps based on a textbook lesson? How would you design these for students who need remedial work?

Reading cards allow students to monitor or evaluate their own comprehension as they proceed from less difficult to more difficult cards. Students can choose their own ‘level’ of card to read: if a card is too simple, they can jump forward; if a card is too difficult, they can go back to a simpler card.

Activity 4: Making reading cards

Make a very simple set of reading cards. You can choose English vocabulary, a very short poem or story, or a set of facts for a subject (for example, names of animals or parts of the body).

- Get scissors, stiff card and paste.

- Cut out six cards – large enough for a student to hold and read easily.

- Select vocabulary or a very short text.

- Write the text on one side of the card.

- Draw or paste pictures, if appropriate.

- Write simple questions about the text on the other side of the card.

Plan a 30-minute session where you give the cards to a small group of students (no more than six). Have them read the cards and answer the questions in their notebooks.

You could organise this group at the same time and in the same way as your small reading aloud group (Activity 2). The rest of the class must be given quiet work to do on their own. Tell the class that everyone will have a chance to work in a group with the reading cards. Explain that the texts are short and the questions are simple, so students should be able to answer them on their own. It is a chance for students to develop the skill of independent working.

You can monitor and evaluate your students’ silent reading by seeing how many cards they read in the time given, at what level, and whether or not they get the answers right. You can also ask your own questions to assess students’ understanding.

In the next section, the focus is on guided reading in ability groups. As you read, think about how reading cards could be used for guided reading.

4 Whole-class guided reading in groups

In guided reading, you organise the whole class into reading ability groups. Each group has individual books or reading cards, or a shared book geared to their reading level.

You spend time with each group, listening to individual students take turns to read aloud. As you work with each group, the other groups must be working independently.

- Have you ever done this, or seen this done?

- What do you think are the benefits of this method? What do you think the disadvantages of this method are?

- What do you need to know about your class in order to group them for reading?

Students will read at different speeds and finish at different times. When you set up students to read in groups, it is important to give them an additional task to do when they finish their reading, such as drawing pictures of characters, completing worksheets, writing a new ending to the story or designing a new cover for the book. This additional task can act as a reward and keep students motivated.

See Resource 2, ‘Using groupwork’.

Video: Using groupwork |

In the final case study, a teacher organises guided reading in a challenging situation.

Case Study 2: Mrs Jena manages guided reading groups

Mrs Jena teaches English to a multi-grade class with 46 Class IV–VI students, who are at different reading levels. She planned for a guided reading session for two periods of 80 minutes’ total duration.

Grouping and resources

First, I made students sit in six groups: five groups of eight and one group of six. I took the help of four students to organise the seating, calling out the name of each student and assigning a group to him or her. While assigning a student to each group, I was careful to ensure that students of similar reading ability were grouped together.

Students in one group could barely read any English, so I gave this group a big book of a Class I story. Students in two groups could read fairly fluently. To one of these groups I gave story books I had borrowed from the school library, and to the other group I gave a collection of simple stories I had been compiling from the children’s section of the newspaper. Students in two other groups were familiar with English letters and sounds, and could recognise a number of words, so I had them use reading cards with words and pictures and simple questions. I made these cards earlier in the year, with the help of the older students.

The six students in the last group required special help: one child was blind, one was dyslexic and four were migrant students who had joined the school only ten days earlier. I gave the blind student tactile letters that I had cut out from sandpaper, as was advised in training on inclusive education I attended in the summer. I told her to feel these letters and guess what they were, and that I would come back to help her. To the other five I gave a large picture book that my own son has now outgrown reading. I told this group to take turns to look at the picture book and talk quietly about what they could see in the pictures, and that I would come back to help them.

Monitoring and assessment

I planned to observe three groups of students: two of students struggling to read and one with fluent readers. Within the 80-minute double period, I also wanted to ensure that I spent time with all the groups of students.

Once the students settled in their groups, I spent about five minutes moving around from group to group, ensuring that they were all reading and had understood what was expected of them. Once I was satisfied they were settled, I spent 10–15 minutes with each group, listening to each student read a portion of the story, helping them where needed and asking them questions to gauge how much they had understood of what they had read. As I did this, I used a checklist I had prepared beforehand against each student and made very brief notes where necessary.

Classroom management

By the time I reached the third group, two students in another group had started quarrelling. Most students in the first group had finished reading what was assigned to them and were clamouring for my attention. For a moment, I felt flustered. I had planned to spend more time with the third group because they have been struggling to read, despite their best efforts. I had to act quickly. I separated the two students who were quarrelling and put them into different groups, telling them to help others and that I would be watching them to see if they could achieve this. I asked some of the students who had finished reading to make drawings in their notebooks, depicting the story. I asked two others to read aloud the picture book to the last group. Only then was I able to spend the next 20 minutes with the third group.

By this time, the noise level in the class had been steadily rising as students had either finished reading or become restless. I tried my counting strategy; my students know that when I start counting slowly up to five, they must settle back into their places and stop making noise. Only five minutes were left before it was lunch break. I quickly gave them a homework assignment of reading and copying the label of any three products they find in their house or neighbourhood shop. I called the last group of six students aside and asked them to draw any three products and write the first letter as their home assignment. I asked the blind student to ask her mother to name three products and for her to repeat them in the next class.

I made a note in my diary soon after the bell: to make time in the next class to work with students in the group who were given the library books, and the names of students whom I did not hear read that day.

Pause for thought Mrs Jena ran a very complex, multi-levelled set of classroom activities in a large class. There was a lot going on. Reflect on how your class is similar to or different from Mrs Jena’s. To finish this unit, answer the following questions about Mrs Jena’s techniques:

|

If you do not feel able to do everything that Mrs Jena did, we hope this unit has given you some ideas and encouragement to try out new routines and resources for reading English in your classroom.

5 Summary

In this unit you have focused on developing and monitoring reading, and moving from reading aloud to silent reading in English. You have looked at reading cards as a resource, and you have looked at management issues in reading group work. You have also considered assessment of reading aloud and silent reading.

One of the greatest benefits of knowing how to read is that, once the skill is mastered, your students can go on to read whatever they find interesting. They can go forward on their own, without waiting for the rest of the class or the teacher to tell them what to read. We hope the activities and case studies in this unit help you to develop your classroom English reading routines.

Other Elementary English teacher development units on this topic are:

- Letters and sounds of English

- Storytelling

- Shared reading

- Planning around a text

- Promoting the reading environment.

Resources

Resource 1: Monitoring and giving feedback

Improving students’ performance involves constantly monitoring and responding to them, so that they know what is expected of them and they get feedback after completing tasks. They can improve their performance through your constructive feedback.

Monitoring

Effective teachers monitor their students most of the time. Generally, most teachers monitor their students’ work by listening and observing what they do in class. Monitoring students’ progress is critical because it helps them to:

- achieve higher grades

- be more aware of their performance and more responsible for their learning

- improve their learning

- predict achievement on state and local standardised tests.

It will also help you as a teacher to decide:

- when to ask a question or give a prompt

- when to praise

- whether to challenge

- how to include different groups of students in a task

- what to do about mistakes.

Students improve most when they are given clear and prompt feedback on their progress. Using monitoring will enable you to give regular feedback, letting your students know how they are doing and what else they need to do to advance their learning.

One of the challenges you will face is helping students to set their own learning targets, also known as self-monitoring. Students, especially struggling ones, are not used to having ownership of their own learning. But you can help any student to set their own targets or goals for a project, plan out their work and set deadlines, and self- monitor their progress. Practising the process and mastering the skill of self-monitoring will serve them well in school and throughout their lives.

Listening to and observing students

Most of the time, listening to and observing students is done naturally by teachers; it is a simple monitoring tool. For example, you may:

- listen to your students reading aloud

- listen to discussions in pair or groupwork

- observe students using resources outdoors or in the classroom

- observe the body language of groups as they work.

Make sure that the observations you collect are true evidence of student learning or progress. Only document what you can see, hear, justify or count.

As students work, move around the classroom in order to make brief observation notes. You can use a class list to record which students need more help, and also to note any emerging misunderstandings. You can use these observations and notes to give feedback to the whole class or prompt and encourage groups or individuals.

Giving feedback

Feedback is information that you give to a student about how they have performed in relation to a stated goal or expected outcome. Effective feedback provides the student with:

- information about what happened

- an evaluation of how well the action or task was performed

- guidance as to how their performance can be improved.

When you give feedback to each student, it should help them to know:

- what they can actually do

- what they cannot do yet

- how their work compares with that of others

- how they can improve.

It is important to remember that effective feedback helps students. You do not want to inhibit learning because your feedback is unclear or unfair. Effective feedback is:

- focused on the task being undertaken and the learning that the student needs to do

- clear and honest, telling the student what is good about their learning as well as what requires improvement

- actionable, telling the student to do something that they are able to do

- given in appropriate language that the student can understand

- given at the right time – if it’s given too soon, the student will think ‘I was just going to do that!’; too late, and the student’s focus will have moved elsewhere and they will not want to go back and do what is asked.

Whether feedback is spoken or written in the students’ workbooks, it becomes more effective if it follows the guidelines given below.

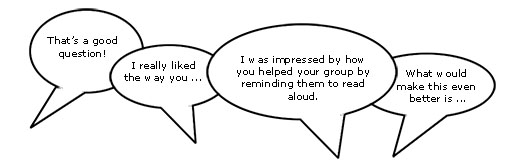

Using praise and positive language

When we are praised and encouraged, we generally feel a great deal better than when we are criticised or corrected. Reinforcement and positive language is motivating for the whole class and for individuals of all ages. Remember that praise must be specific and targeted on the work done rather than about the student themselves, otherwise it will not help the student progress. ‘Well done’ is non-specific, so it is better to say one of the following:

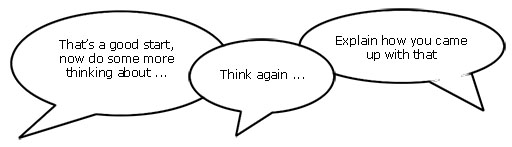

Using prompting as well as correction

The dialogue that you have with your students helps their learning. If you tell them that an answer is incorrect and finish the dialogue there, you miss the opportunity to help them to keep thinking and trying for themselves. If you give students a hint or ask them a further question, you prompt them to think more deeply and encourage them to find answers and take responsibility for their own learning. For example, you can encourage a better answer or prompt a different angle on a problem by saying such things as:

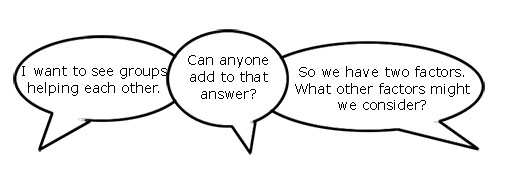

It may be appropriate to encourage other students to help each other. You can do this by opening your questions to the rest of the class with such comments as:

Correcting students with a ‘yes’ or ‘no’ might be appropriate to tasks such as spelling or number practice, but even here you can prompt students to look for emerging patterns in their answers, make connections with similar answers or open a discussion about why a certain answer is incorrect.

Self-correction and peer correction is effective and you can encourage this by asking students to check their own and each other’s work while doing tasks or assignments in pairs. It is best to focus on one aspect to correct at a time so that there is not too much confusing information.

Resource 2: Using groupwork

Groupwork is a systematic, active, pedagogical strategy that encourages small groups of students to work together for the achievement of a common goal. These small groups promote more active and more effective learning through structured activities.

The benefits of groupwork

Groupwork can be a very effective way of motivating your students to learn by encouraging them to think, communicate, exchange ideas and thoughts, and make decisions. Your students can both teach and learn from others: a powerful and active form of learning.

Groupwork is more than students sitting in groups; it involves working on and contributing to a shared learning task with a clear objective. You need to be clear about why you are using groupwork for learning and know why this is preferable to lecturing, pair work or to students working on their own. Thus groupwork has to be well-planned and purposeful.

Planning groupwork

When and how you use groupwork will depend on what learning you want to achieve by the end of the lesson. You can include groupwork at the start, the end or midway through the lesson, but you will need to allow enough time. You will need to think about the task that you want your students to complete and the best way to organise the groups.

As a teacher, you can ensure that groupwork is successful if you plan in advance:

- the goals and expected outcomes of the group activity

- the time allocated to the activity, including any feedback or summary task

- how to split the groups (how many groups, how many students in each group, criteria for groups)

- how to organise the groups (role of different group members, time required, materials, recording and reporting)

- how any assessment will be undertaken and recorded (take care to distinguish individual assessments from group assessments)

- how you will monitor the groups’ activities.

Groupwork tasks

The task that you ask your students to complete depends on what you what them to learn. By taking part in groupwork, they will learn skills such as listening to each other, explaining their ideas and working cooperatively. However, the main aim is for them to learn something about the subject that you are teaching. Some examples of tasks could include the following:

- Presentations: Students work in groups to prepare a presentation for the rest of the class. This works best if each group has a different aspect of the topic, so they are motivated to listen to each other rather than listening to the same topic several times. Be very strict about the time that each group has to present and decide on a set of criteria for a good presentation. Write these on the board before the lesson. Students can the use the criteria to plan their presentation and assess each other’s work. The criteria could include:

- Was the presentation clear?

- Was the presentation well-structured?

- Did I learn something from the presentation?

- Did the presentation make me think?

- Problem solving: Students work in groups to solve a problem or a series of problems. This could include conducting an experiment in science, solving problems in mathematics, analysing a story or poem in English, or analysing evidence in history.

- Creating an artefact or product: Students work in groups to develop a story, a piece of drama, a piece of music, a model to explain a concept, a news report on an issue or a poster to summarise information or explain a concept. Giving groups five minutes at the start of a new topic to create a brainstorm or mind map will tell you a great deal about what they already know, and will help you pitch the lesson at an appropriate level.

- Differentiated tasks: Groupwork is an opportunity to allow students of different ages or attainment levels to work together on an appropriate task. Higher attainers can benefit from the opportunity to explain the work, whereas lower attainers may find it easier to ask questions in a group than in a class, and will learn from their classmates.

- Discussion: Students consider an issue and come to a conclusion. This may require quite a bit of preparation on your part in order to make sure that the students have enough knowledge to consider different options, but organising a discussion or debate can be very rewarding for both you and them.

Organising groups

Groups of four to eight are ideal but this will depend on the size of your class, the physical environment and furniture, and the attainment and age range of your class. Ideally everyone in a group needs to see each other, talk without shouting and contribute to the group’s outcome.

- Decide how and why you will divide students into groups; for example, you may divide groups by friendship, interest or by similar or mixed attainment. Experiment with different ways and review what works best with each class.

- Plan any roles you will give to group members (for example, note taker, spokesperson, time keeper or collector of equipment), and how you will make this clear.

Managing groupwork

You can set up routines and rules to manage good groupwork. When you use groupwork regularly, students will know what you expect and find it enjoyable. Initially it is a good idea to work with your class to identify the benefits of working together in teams and groups. You should discuss what makes good groupwork behaviour and possibly generate a list of ‘rules’ that might be displayed; for example, ‘Respect for each other’, ‘Listening’, ‘Helping each other’, ‘Trying more than one idea’, etc.

It is important to give clear verbal instructions about the groupwork that can also be written on the blackboard for reference. You need to:

- direct your students to the groups they will work in according to your plan, perhaps designating areas in the classroom where they will work or giving instructions about moving any furniture or school bags

- be very clear about the task and write it on the board in short instructions or pictures. Allow your students to ask questions before you start.

During the lesson, move around to observe and check how the groups are doing. Offer advice where needed if they are deviating from the task or getting stuck.

You might want to change the groups during the task. Here are two techniques to try when you are feeling confident about groupwork – they are particularly helpful when managing a large class:

- ‘Expert groups’: Give each group a different task, such as researching one way of generating electricity or developing a character for a drama. After a suitable time, re-organise the groups so that each new group is made up of one ‘expert’ from all the original groups. Then give them a task that involves collating knowledge from all the experts, such as deciding on what sort of power station to build or preparing a piece of drama.

- ‘Envoys’: If the task involves creating something or solving a problem, after a while, ask each group to send an envoy to another group. They could compare ideas or solutions to the problem and then report back to their own group. In this way, groups can learn from each other.

At the end of the task, summarise what has been learnt and correct any misunderstandings that you have seen. You may want to hear feedback from each group, or ask just one or two groups who you think have some good ideas. Keep students’ reporting brief and encourage them to offer feedback on work from other groups by identifying what has been done well, what was interesting and what might be developed further.

Even if you want to adopt groupwork in your classroom, you may at times find it difficult to organise because some students:

- are resistant to active learning and do not engage

- are dominant

- do not participate due to poor interpersonal skills or lack of confidence.

To become effective at managing groupwork it is important to reflect on all the above points, in addition to considering how far the learning outcomes were met and how well your students responded (did they all benefit?). Consider and carefully plan any adjustments you might make to the group task, resources, timings or composition of the groups.

Research suggests that learning in groups need not be used all the time to have positive effects on student achievement, so you should not feel obliged to use it in every lesson. You might want to consider using groupwork as a supplemental technique, for example as a break between a topic change or a jump-start for class discussion. It can also be used as an ice-breaker or to introduce experiential learning activities and problem solving exercises into the classroom, or to review topics.

Additional resources

- Karadi Tales: http://www.karaditales.com/

- National Book Trust India: http://www.nbtindia.gov.in/

- NCERT textbooks: http://www.ncert.nic.in/ NCERTS/ textbook/ textbook.htm

- Teachers of India classroom resources: http://www.teachersofindia.org/ en

References

Acknowledgements

Except for third party materials and otherwise stated below, this content is made available under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike licence (http://creativecommons.org/ licenses/ by-sa/ 3.0/). The material acknowledged below is Proprietary and used under licence for this project, and not subject to the Creative Commons Licence. This means that this material may only be used unadapted within the TESS-India project and not in any subsequent OER versions. This includes the use of the TESS-India, OU and UKAID logos.

Grateful acknowledgement is made to the following sources for permission to reproduce the material in this unit:

Figure 1: Example of reading card from Reading Card 1, English 100, Central Institute of English and Foreign Languages: CIEFL Hyderabad, 2000.

Figure 2: Example of reading card from Reading Cards 100 and 41, English 100, CIEFL: CIEFL Hyderabad, 2000.

Every effort has been made to contact copyright owners. If any have been inadvertently overlooked the publishers will be pleased to make the necessary arrangements at the first opportunity.

Video (including video stills): thanks are extended to the teacher educators, headteachers, teachers and students across India who worked with The Open University in the productions.