Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Thursday, 5 February 2026, 7:17 AM

TI-AIE: Developing and monitoring writing

What this unit is about

This unit is about strategies you can use to encourage writing in English in your classroom. The main focus is on supporting your students in composition and drafting. Of course, spelling, handwriting and punctuation are also important. But when students are drafting and composing their ideas of what to write about, they will be practising the mechanical skills at the same time.

Writing is meant to be read, so a focus on writing will always integrate a focus on reading. When you and your students talk about writing, you also develop their oral language skills.

What you can learn in this unit

- To identify composition and transcription tasks to use with your students.

- To plan drafting activities for your students.

- To evaluate your students’ attempts to spell English.

1 Composition and transcription

Start by thinking about the two key processes of writing: composition and transcription, in an activity for you.

In any language, writing involves taking thoughts from inside the mind and putting them onto paper. There are two main aspects to writing:

- Composition: An authoring role that involves getting ideas, deciding on the form of the written text (a poem, a story, a report, a recipe, a set of instructions, etc.), thinking about who will read the writing and why. Drafting is an important part of composition. The first attempt at writing anything is seldom perfect.

- Transcription: A secretarial role that involves paying attention to how the writing is presented so that others can read and understand it. This includes aspects such as handwriting, spelling, punctuation and the general layout. In transcription, the writer can work from a final draft to a finished piece of writing.

When students begin to write, in English or any language, they can find it difficult to control both composition and transcription at the same time, and perform equally well in each of them. When students focus on getting ideas for a piece of writing, they may not spell the associated words correctly; when they focus on spelling words correctly, their ideas for a story or a poem may be less creative.

Pause for thought

|

In Case Study 1, a teacher focuses on composition and drafting.

Case Study 1: Mr Satyam encourages drafting

Mr Satyam teaches English to Class VI students at a school in a village outside Bangalore.

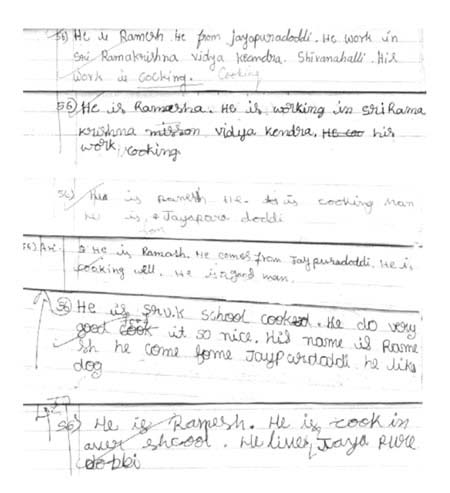

I drew an outline of a man on the board. I asked a few questions to get the students thinking, such as ‘Who is he?’ and ‘Where does he live?’ I prompted the students to ask more questions about the outline of the man. They came up with their own ideas such as ‘What work does he do?’ and ‘What does he like?’

They decided that the figure would be the school cook, Ramesh. I told the students to decide how to answer the questions. I wrote some of their suggestions around the figure, on the board.

Then I told them to write their own sentences in their notebooks [Figure 1]. From these drafts, students wrote portraits of Ramesh.

Pause for thought

|

Mr Satyam used a similar method to help students draft their ideas to write about Independence Day celebrations. He gave them a diagram and had them write sentences for each box (Figure 2).

Do you think you could use this diagram to start students writing on other topics?

Activity 1: Encouraging drafting – a planning activity

Taking the example of Mr Satyam in Case Study 1 as a guide, plan a drafting activity for your students.

The topic can come from your textbook, a topic in a subject such as science or history, or a real-life situation. You can give instructions verbally, or use a diagram similar to Figure 2 to help students draft sentences in English.

In drafting, the focus is on composition, not transcription. Tell your students that they should first concentrate on sequencing and structuring, and later they can work on spelling and presentation.

From their drafts, plan the next lesson where students will make improvements and finish their writing.

2 Giving feedback

When giving feedback on students’ writing, focus on just one or two aspects at a time. This will ensure they do not become dispirited by over-correction or overwhelmed by too much feedback. When giving feedback on a first draft, it is important to praise the student’s efforts at composition. Did the student have a good idea for a story? Did the student write interesting dialogue? Did the student remember to write the main points of a report? Did the student make a good effort to write in English?

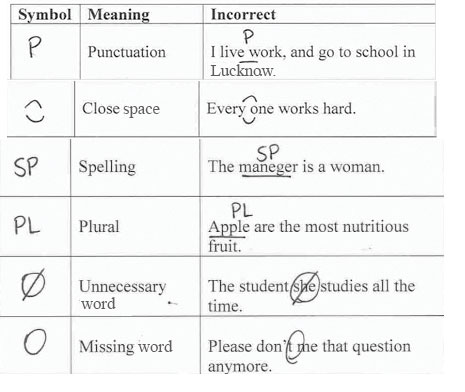

For feedback on transcription, mark their drafts with symbols and discuss with the whole class what these mean. Examples are shown in Figure 3.

Even if your class is large, it is important that you give individual feedback to all students. There is no single way of giving feedback or remarks. What needs to be kept in mind is that feedback should create a positive attitude towards writing. In the next case study, a teacher must decide how to give feedback on a student’s writing.

See Resource 1, ‘Monitoring and feedback’, to learn more about the methods to evaluate and record student progress.

Case Study 2: Ms Afreen assesses dictation

Ms Afreen teaches in a government school where all the students are first-generation school goers.

I gave students dictation from the textbook. When the students handed me their work, I reviewed it and saw that a ten-year-old girl had spelled the words ‘pencil’, ‘rubber’ and ‘boxes’ as follows:

- pensl

- rubr

- bokss.

My first reaction was to correct these mistakes. But I could see that the girl knew the initial sounds of English words. She recognised consonant sounds, and she knew that some words began with a capital letter. She was not yet distinguishing English vowel sounds in between consonants. I can see that she was using her oral knowledge of English to make a good attempt at spelling, although this was not always correct in writing, as can be seen from the use of ‘k’ for ‘x’ and ‘s’ for ‘c’. I decided she was making a good attempt at writing based on her current understanding of English letters and sounds.

I praised her attempts. But I also told her to read her writing more carefully and to check her spelling using a dictionary. I encouraged her to read more, because the more she reads in English, the better her English spelling will be.

I do not ignore errors in writing, and I give students feedback and correction. But I try to see how their mistakes give me clues about their thinking process and developmental level. Their mistakes show me what I need to plan next.

Activity 2: Errors and assessment

Errors in writing can be categorised broadly as:

- ‘silly mistakes’ or slips that students can correct on their own once they have been pointed out to them

- ‘misunderstandings’ that students cannot correct themselves and that need to be explained by teachers

- ‘attempts’ where students try out something but make mistakes because they do not yet have the required language skill or knowledge.

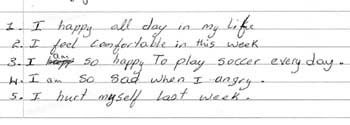

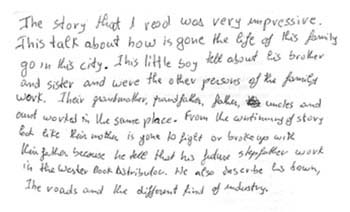

Look at two pieces of writing by students (Figures 4 and 5). Do they show evidence of ‘silly mistakes’, ‘misunderstandings’ or ‘attempts’? How you would evaluate the writing based on the concepts of ‘composition’ (the author) and ‘transcription’ (the secretary) that you read about at the beginning of this unit? What would you say to each student, to give them encouraging feedback? Talk about these examples with other teachers in your school and compare your ideas for evaluation and feedback.

When students speak and write in English they sometimes miss out English words if their home language does not use these words, like articles such as ‘a’, ‘the’ or ‘an’. Make this an opportunity to talk to students about the different structures of English compared to other languages.

People who are multilingual often mix languages in their speaking and in their writing – this is common everywhere in the world. You can make this tendency visible to students by inviting those who speak different dialects or languages at home to talk about a topic in their home language, or to write in their home language and read it out or display it to the class. You need to be careful in not to comment or to let other students pass comments. The objective must be to let students see for themselves that mixing languages is natural, and the occasional use of English is like using any other language they already know. Activities that bring students’ home languages into the English classroom will go a long way in helping to shed their inhibitions about speaking in English, and also celebrate the rich multilingualism of our country.

Video: Monitoring and giving feedback |

3 Reading to inspire writing

The more students listen to English and read in English, the better will be their writing in English. When you teach students to speak and read in English, you are also teaching them to write in English. Once students start to read, they can begin to write. Once they write, they will want to read their own and others’ writing. In the final case study, the teacher tries out new ways to inspire this process.

Case Study 3: Mr Bhatt starts with reading to inspire writing

This is an extract adapted from an article written by Hemraj Bhatt, a government school teacher.

Our new textbook was going to break new ground to introduce students directly to English words and sentences, rather than beginning with the letters of the alphabet and making them ‘mug up’ the letters by writing them out. No special importance was to be given to writing. Instead, students were to be given opportunities to hear, read and speak English. Previously, the textbook would dedicate the initial six to eight pages to the English alphabet with related pictures. This tradition of beginning with writing the English alphabet was thus to be broken in the new book. As a conventional teacher, I found it hard to imagine how students would be able to read English words directly before writing the letters.

After attending the training provided, I decided to experiment. I distributed some old English newspapers and students' magazines among my students so that everyone could look at at least three pages. I wrote an English word on the board. For example, a particular student's name was Jaipal. I wrote his name on the board. Now, Jaipal would have to find the English letters ‘J’, ‘A’, ‘I’, ‘P’ and ‘L’ in the newspaper given to him and circle them. Similarly, all students would look for and circle all the letters that appeared in their names in the newspaper given to them.

The students had a lot of fun finding the letters that appeared in their names. They were particularly amused when they saw their entire name in English in the paper and could circle the entire word. This exercise was meant to take the students from words to letters and was successful in doing so. I was surprised to see that students who couldn't identify English letters a few months ago were able to find examples of letters and words in newspapers and magazines. I realised through the newspaper exercises that reading in English can be made fun for students. Most importantly for me as a teacher, I saw that once students began to read in English, they were eager to start writing in English too.

Pause for thought

|

Activity 3: Reading to inspire writing – a planning activity

Read through the activities in Resource 2. In each of these activities there is a link between reading and writing.

- Choose one activity you feel you could try out with your class.

- How will you evaluate the writing students produce from the activity?

- How much will you focus on composition, and how much on transcription?

- Do you think it is important to link reading and writing?

4 Summary

This unit has focused on how you can help students to make progress in English writing, and how you can evaluate their attempts to write in English. Students do not need to be fluent in English grammar or know how to spell English perfectly to start writing in English. With frequent opportunities for drafting and writing, students will practise English spellings and sentence structures.

Other Elementary English teacher development units on this topic are:

- The learning environment.

- Mark making and early writing.

Resources

Resource 1: Monitoring and giving feedback

Improving students’ performance involves constantly monitoring and responding to them, so that they know what is expected of them and they get feedback after completing tasks. They can improve their performance through your constructive feedback.

Monitoring

Effective teachers monitor their students most of the time. Generally, most teachers monitor their students’ work by listening and observing what they do in class. Monitoring students’ progress is critical because it helps them to:

- achieve higher grades

- be more aware of their performance and more responsible for their learning

- improve their learning

- predict achievement on state and local standardised tests.

It will also help you as a teacher to decide:

- when to ask a question or give a prompt

- when to praise

- whether to challenge

- how to include different groups of students in a task

- what to do about mistakes.

Students improve most when they are given clear and prompt feedback on their progress. Using monitoring will enable you to give regular feedback, letting your students know how they are doing and what else they need to do to advance their learning.

One of the challenges you will face is helping students to set their own learning targets, also known as self-monitoring. Students, especially struggling ones, are not used to having ownership of their own learning. But you can help any student to set their own targets or goals for a project, plan out their work and set deadlines, and self- monitor their progress. Practising the process and mastering the skill of self-monitoring will serve them well in school and throughout their lives.

Listening to and observing students

Most of the time, listening to and observing students is done naturally by teachers; it is a simple monitoring tool. For example, you may:

- listen to your students reading aloud

- listen to discussions in pair or groupwork

- observe students using resources outdoors or in the classroom

- observe the body language of groups as they work.

Make sure that the observations you collect are true evidence of student learning or progress. Only document what you can see, hear, justify or count.

As students work, move around the classroom in order to make brief observation notes. You can use a class list to record which students need more help, and also to note any emerging misunderstandings. You can use these observations and notes to give feedback to the whole class or prompt and encourage groups or individuals.

Giving feedback

Feedback is information that you give to a student about how they have performed in relation to a stated goal or expected outcome. Effective feedback provides the student with:

- information about what happened

- an evaluation of how well the action or task was performed

- guidance as to how their performance can be improved.

When you give feedback to each student, it should help them to know:

- what they can actually do

- what they cannot do yet

- how their work compares with that of others

- how they can improve.

It is important to remember that effective feedback helps students. You do not want to inhibit learning because your feedback is unclear or unfair. Effective feedback is:

- focused on the task being undertaken and the learning that the student needs to do

- clear and honest, telling the student what is good about their learning as well as what requires improvement

- actionable, telling the student to do something that they are able to do

- given in appropriate language that the student can understand

- given at the right time – if it’s given too soon, the student will think ‘I was just going to do that!’; too late, and the student’s focus will have moved elsewhere and they will not want to go back and do what is asked.

Whether feedback is spoken or written in the students’ workbooks, it becomes more effective if it follows the guidelines given below.

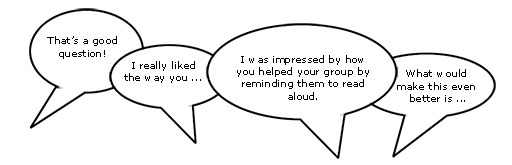

Using praise and positive language

When we are praised and encouraged, we generally feel a great deal better than when we are criticised or corrected. Reinforcement and positive language is motivating for the whole class and for individuals of all ages. Remember that praise must be specific and targeted on the work done rather than about the student themselves, otherwise it will not help the student progress. ‘Well done’ is non-specific, so it is better to say one of the following:

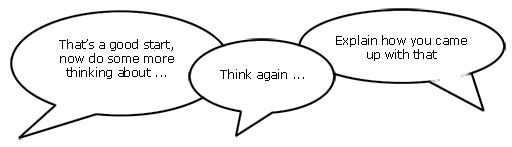

Using prompting as well as correction

The dialogue that you have with your students helps their learning. If you tell them that an answer is incorrect and finish the dialogue there, you miss the opportunity to help them to keep thinking and trying for themselves. If you give students a hint or ask them a further question, you prompt them to think more deeply and encourage them to find answers and take responsibility for their own learning. For example, you can encourage a better answer or prompt a different angle on a problem by saying such things as:

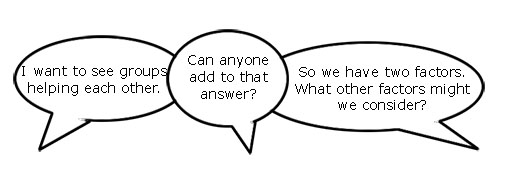

It may be appropriate to encourage other students to help each other. You can do this by opening your questions to the rest of the class with such comments as:

Correcting students with a ‘yes’ or ‘no’ might be appropriate to tasks such as spelling or number practice, but even here you can prompt students to look for emerging patterns in their answers, make connections with similar answers or open a discussion about why a certain answer is incorrect.

Self-correction and peer correction is effective and you can encourage this by asking students to check their own and each other’s work while doing tasks or assignments in pairs. It is best to focus on one aspect to correct at a time so that there is not too much confusing information.

Resource 2: Activities to develop writing

- Draw a picture of a character from a story. It could be from your textbook, or from a story everyone knows well. Write five or six sentences in English about it.

- Rewrite the jumbled sentences provided, to make a meaningful paragraph.

- Write a paragraph summarising a recent lesson in any topic and illustrate it.

- Make a bookmark based on a story or a poem. Draw a character or write a brief summary on one side of the bookmark. On the other, write the title of the story and the name of the author.

- Write a letter to the author of a book. (If the author is living, you can try to find the address from your state textbook society and post them some of the students’ letters.)

- (For older students) Make a big book based on a story for students in lower classes.

- Set an English quiz with at least ten questions based on a recent lesson on any topic. This helps to reinforce learning as well as to practise writing. After they have tried the quiz, ask the students to exchange papers and check each other’s work.

- Tell the students a story but do not tell them the ending. Ask them to guess what happened at the end and write it down. Remember that there are no right or wrong endings to a story.

- Ask the students to bring one small object to the class, such as a pencil, box, leaf, etc. Divide the class into groups of five or six. All the things they brought are placed in the centre of the group. With a limit of ten minutes, each group discusses a possible story based on the objects they have brought. They then write out the story (which should be a minimum of five to six lines long). One student from each group narrates the story to the class. The best story is the one that includes all the objects the group had brought in.

- Divide the class into groups of five. Each group has one piece of paper to write on, and at least one pencil. Without prior discussion, the group should come up with a story, with each student in the group contributing one sentence at a time. Select one student as the ‘starter’ in each group. The starter writes one sentence on the piece of paper, which now goes to the next student in the group. The second student contributes a sentence that combines with the one already there. The paper keeps going around until the story is complete. Anyone can decide at any point that the story cannot progress any more. If the others agree, the group selects a different starter to write a fresh sentence for a new story – or the next chapter of the first story!

Additional resources

- RVEC Bangalore: http://www.rvec.in/

- Teachers of India classroom resources: http://www.teachersofindia.org/ en

References

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements

Except for third party materials and otherwise stated below, this content is made available under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike licence (http://creativecommons.org/ licenses/ by-sa/ 3.0/). The material acknowledged below is Proprietary and used under licence for this project, and not subject to the Creative Commons Licence. This means that this material may only be used unadapted within the TESS-India project and not in any subsequent OER versions. This includes the use of the TESS-India, OU and UKAID logos.

Grateful acknowledgement is made to the following sources for permission to reproduce the material in this unit:

Figure 3: provided by Mythili Ramchand.

Figures 4 and 5: extract from http://esol.coedu.usf.edu/.

Every effort has been made to contact copyright owners. If any have been inadvertently overlooked the publishers will be pleased to make the necessary arrangements at the first opportunity.

Video (including video stills): thanks are extended to the teacher educators, headteachers, teachers and students across India who worked with The Open University in the productions.