Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Thursday, 5 February 2026, 10:27 AM

TI-AIE: Supporting independent writing in English

What this unit is about

Students at secondary school are expected to write various texts in English. This might range from words to learn; notes about grammar, or sentences such as answers to comprehension questions; to longer texts, such as compositions, stories, letters, reports, applications and so on. These types of texts should require students to communicate through writing using their own ideas and language. However, often what students write is copied from the textbook or blackboard, or they reproduce dictated or memorised answers. Most students do not compose texts themselves.

While this copying and memorising may help some students in exams, it doesn’t help them to develop the skills they need in order to write in English independently for real-life purposes. This is a skill that will be useful for their future personal and professional lives.an opportunity to think critically and imaginatively. Students will develop the skills and confidence to write independently if they get lots of opportunities to talk about their ideas and practise speaking and writing about them. It is not enough for them to see – and copy – examples of ‘good’ language. It is also through trying to express themselves that students become better writers.

This unit explores two strategies that you can use to help your students move from copying and memorising to composing their own texts:

- Facilitating student talk on the chosen topic. By talking to each other and you, students share and develop their ideas. This also allows them to practise and experiment with the language to express their ideas in writing.

- Teaching students writing independently involves giving them access to language that they can model their writing on.

When students are writing independently, they will make mistakes. This is a normal part of language learning. By noticing and recording the mistakes, you can direct student learning more effectively through your use of positive and encouraging feedback.

What you can learn in this unit

- Facilitating student talk to support the development of students’ writing.

- Making accessible models for student writing.

- Ways to manage the correction of your students’ written work.

1 Using discussion to support student writing

Students are expected to write answers to comprehension questions about a lesson or passage in English, as in the following example.

Class VIII students study a passage called ‘The Summit Within’ from NCERT’s textbook Honeydew, which is about someone who climbs to the top of Mount Everest. After reading the text, they are expected to answer the questions below:

Answer the following questions:

- i.What are the three qualities that played a major role in the author’s climb?

- ii.Why is adventure, which is risky, also pleasurable?

- iii.What was it about Mount Everest that the author found irresistible?

- iv.One does not do it (climb a high peak) for fame alone. What does one do it for, really?

- v.‘He becomes conscious in a special manner of his own smallness in this large universe.’ This awareness defines an emotion mentioned in the first paragraph. What is this emotion?

- vi.What were the ‘symbols of reverence’ left by members of the team on Everest?

- vii.What, according to the writer, did his experience as an ‘Everester’ teach him?

Pause for thought Have you taught this lesson? If so, how have you helped your students to answer these questions? If you have not taught the lesson, how would you help students to answer the questions in their own words? Some teachers ask students to copy the answers from the blackboard. But when students do this, it is difficult to know if they have understood the question or the lesson. Just because students can copy sentences or paragraphs, it doesn’t mean that they understand what they are writing. Also, when copying, students are not practising English much. It may help their spelling, but they are not thinking about how the language works. If students write their own sentences and text, they have to think about the grammar – the tenses and structures – and vocabulary. They focus on the meaning of what they want to communicate, and this helps them become able to use the language independently. |

One way you can help students to write their own responses to questions such as these is by allowing them to discuss the questions. When you give your students time to discuss the questions in pairs or groups before they write answers, they have to communicate what they understand to each other, learning from each other. Having time to talk and think and by discussing things with classmates can help your students make the first steps in writing sentences independently.

2 Discussing ideas through groupwork

If students are not used to writing by themselves it can be quite a big step to ask them to try this. But by working in small groups, students can support each other in understanding a text, develop their ideas and practise the language that they can then use in their written responses.

Activity 1: Try in the classroom – answering textbook questions in groups

In the textbook passage called ‘The Summit Within’ from NCERT’s textbook Honeydew, students are expected to write answers in English to a number of comprehension questions.

The next time you teach a lesson with an activity like this, ask your students to answer the comprehension questions at the end of the lesson in groups. This will allow them to develop their ideas with each other and find the language to answer the questions together.

- In class, divide the students into groups of four. If they are sitting on benches, ask the students on the first bench to turn around so that they are facing the students on the second bench. Repeat that with the other rows so that groups are formed without too much noise. Ask one student from each group to be the ‘secretary’ who writes down the responses. For more on groupwork see Resource 1.

- Ask students to discuss their answers to the questions and write them down. Tell them that they should not copy sentences directly from the lesson. Give them a time limit for this task (ten minutes, for example).

- Move around the groups and monitor their work. This ensures that the students understand what they are doing, and feel more confident to discuss problems. Make sure that all the students have an opportunity to contribute to the discussion.

- When they have finished, ask a representative from two or three groups to read aloud an answer. Discuss the answers as a class, and how they can be improved. If it is possible, check each group’s questions and answers.

Pause for thought Here is a question for you to think about after trying this activity. If possible, discuss this question with a colleague. After the lesson, think about your students’ learning. Did this activity engage them in communicating what they understood to each other? |

Having students work together to answer questions about passages in the textbook can help them build up the skills and confidence to write answers to these questions. One way to extend students’ understanding further is to ask them to compose their own comprehension questions about a text.

Activity 2: Try in the classroom – using groupwork to help students write questions and answers about a text

You can try out this activity with any lesson or passage, and any class.

- Set up groupwork as in Activity 1.

- Ask different groups to read through different paragraphs of the text. For example, Group 1 could look at the first two paragraphs; Group 2 could look through the third and fourth paragraphs; and so on. It doesn’t matter if several groups are looking at the same paragraphs.

- Ask each group to work together to write three questions about the section of the text they have read – these questions should check the students’ understanding of the text. Provide some examples to the whole class of the kind of questions you mean before they start working in groups. Give a time limit for the activity (for example, ten minutes).

- Ask your students to discuss their questions and what the correct answers to the questions are. Have the group secretary write these questions and answers down.

- When the students have finished writing their questions, ask the groups to exchange their questions, so that every group gets a different set of questions to the ones they have written.

- Ask students to discuss and write answers to the questions. Tell them that they should not copy sentences directly from the textbook. Once again, give a time limit.

- Move around the groups and monitor their work. This ensures that the students understand what they are doing and feel more confident to discuss problems.

- Ask two or three groups to read aloud one or two questions and the answers; discuss the answers, and how they can be improved. If it is possible, check each group’s questions and answers.

Pause for thought Here are some questions for you to think about after trying this activity. If possible, discuss these questions with a colleague. After the lesson, think about your students’ learning. Were there groups that found it difficult to write questions? How could you help them the next time you do this exercise? |

There are ways that you can help support your students’ writing by giving them some of the language that they need to write their responses. You will find out more about this in the following case study.

Case Study 1: Mr Singh uses student discussion with comprehension questions

Mr Singh teaches English to Class VIII. He recently tried a technique to help his students to answer comprehension questions without copying directly from the lesson, and this involved getting his students to work in groups. The lesson was ‘The Summit Within’ from Honeydew, NCERT’s textbook for Class VIII.

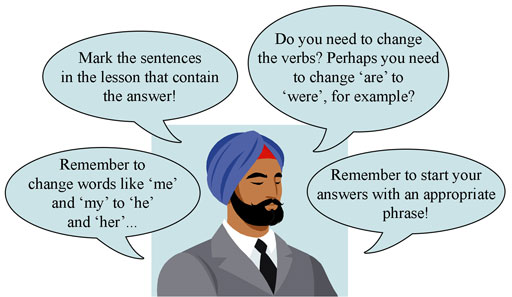

After doing a pre-reading exercise, we read the passage ‘The Summit Within’ together. When we finished, I first asked students what the text was about to get a general sense of whether they had understood. I then moved to the post-reading activity, which was answering the comprehension questions at the end of the lesson. I decided that we would answer the first question together as a class.

I asked my students to read the first comprehension question: ‘What are the three qualities that played a major role in the author’s climb?’ I made sure that they could understand the question by asking them to give a translation. Then I gave my students a list of useful phrases to begin answers, such as: ‘The three qualities that played a major role are …’.

I asked them to read the first paragraph and underline the sentences that contained the answer. The students underlined the following:

The simplest answer would be, as others have said, ‘Because it is there.’ It presents great difficulties. Man takes delight in overcoming obstacles. The obstacles in climbing a mountain are physical. A climb to a summit means endurance, persistence and will power.

I asked them to locate the exact words that would describe the three qualities. Most of the students answered ‘endurance’, ‘persistence’ and ‘will power’, but a few asked me whether ‘overcoming obstacles’ wasn’t another important point.

I was happy that the students could narrow down their search for the most appropriate words that would answer the question. I then asked them to find a way to include ‘overcoming obstacles’ in their list of three qualities.

I showed them how to organise the points into an appropriate answer, with a proper beginning and ending. I also made sure that they noted the change of the tense of the verb when writing an answer: ‘are’ would change to ‘were’, and so on. After making the necessary changes in the sentences, this is what they got:

The three qualities that played a major role in the author’s climb were endurance, persistence and will power for overcoming obstacles.

I showed them other ways of writing the same answer, such as:

Endurance, persistence and will power for overcoming obstacles were the three qualities that played a major role in the author’s climb.

I wanted the class to answer the rest of the questions in groups. I asked the class to work in groups of four, and to work together and compose answers to the rest of the questions. I gave them some words and phrases from the lesson to use in their responses. But I reminded them that they should use their own words, and not copy sentences directly from the lesson. I gave them some time to write their answers, and moved around the room to help any students that needed it.

When the time was up, I asked a different group to answer each question. I wrote the answer that the group gave on the blackboard and we discussed whether it answered the question, and whether the group had used their own words in addition to the important words and phrases from the text that they needed to complete their answers. I also corrected any mistakes that the group had made.

By the end of the class, my students were getting better at answering the questions. I really noticed with discussion and a little help with their answers, students were much better able to do the activity, and they felt a lot better about themselves too.

3 Helping students to write independently by modelling language

In Case Study 1, the teacher helped students to write their answers to questions about a text by modelling the answer and giving students some of the language that they needed to compose their responses. Giving students the models or writing frames helps them to slowly build up the skills that they need to write independently.

Here are some different ways that you can provide help:

- Missing words: Provide a text that has words or sentences missing, and that students have to complete themselves. Leave out words or short phrases that students can find in a reading passage. This gives students a lot of support, and works well with well-known stories or summaries of a lesson, for example:

- Anne Frank had a father, a mother and ________. She was born in ________ in ________. The family emigrated to ________, and she went to ________.

- Models: Provide a complete text that students change according to their own contexts. For example, give a description of your mother or father, and ask students to change the key words to describe their own mother or father. Students who are more confident at writing can make more changes and use more of their own language.

- Writing frames: Provide a writing frame of a text that gives students a structure to follow: a formal letter, for example. You can support students more by giving them more information: sentences, sentence prompts, key vocabulary and so on. As students become more familiar with writing formal letters, you can give them less support (see Resource 2 for a sample writing frame).

Now read about how one teacher uses the ‘missing words’ technique in the next case study.

Case Study 2: Mrs Mishra supports his students to write longer texts

Mrs Mishra teaches English to Class IX. She recently tried an activity to help her students to write independently in English by supporting them with the language they needed to do a writing activity at the end of a lesson.

At the end of the chapter that we were studying (in the NCERT Class IX textbook Beehive), there was a writing task:

Pets have unique care and handling requirements and should only be kept by those with the commitment to understand and meet their needs. Give your argument in support of or against this statement.

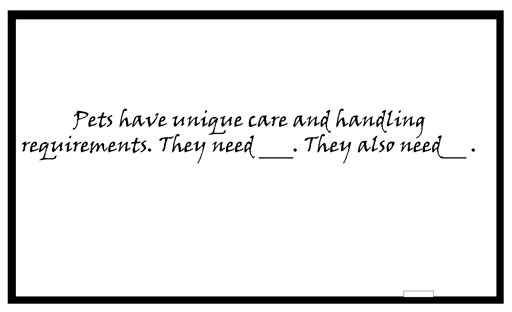

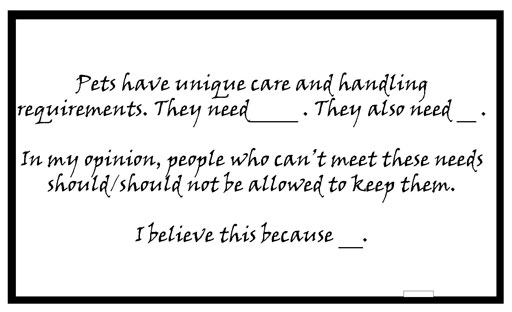

I knew that it would be too difficult for most of my students to write this paragraph – first of all, they wouldn’t really know what to say! So I asked my students to spend a few minutes discussing what requirements pets need. This allowed them to generate some ideas for what they wanted to write. As they were talking, I wrote the following sentences on the board:

When I had finished, I asked students to give some suggestions. A couple of students raised their hands and suggested that animals needed food, water and someone to take care of them if they are ill. I then added some more sentences on the board.

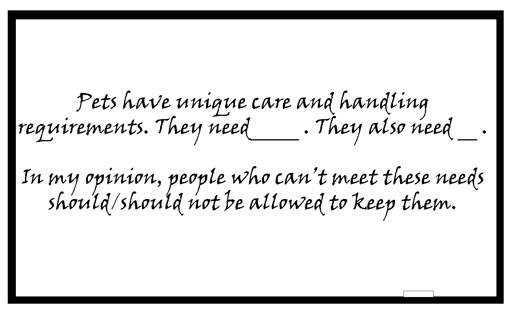

I asked my class to raise their hands if they thought that people who couldn’t meet the needs should be allowed to keep pets. Not many students raised their hands – just a few. I asked Prajit why he thought so. He said that perhaps people couldn’t meet all of the needs, but maybe they could meet some of them, and that was better for the animal than nothing. He expressed this in his home language, so I asked other students in the class if they could help him say this in English. Together they were able to come up with a reply.

I then asked the class to raise their hands if they thought that only people who can meet the needs should be allowed to keep pets. Most of the students raised their hands. They thought that it was not fair for the pets if they did otherwise. Devang thought that pets were like members of the family. I praised him for expressing his opinion and then helped him to say this in English. Now I added another sentence:

Now there was a model paragraph on the blackboard. I asked students to write the paragraph and to complete it with their own thoughts and ideas. I moved around the class as students worked to help with any questions, and to correct mistakes where I could. At the end, each student had written a paragraph, and I encouraged the students who were more confident to write more, and to give more reasons. I asked one or two students to read out their paragraphs. It led to quite an interesting discussion about animal welfare. I never expected that students would come up with so many interesting ideas. By providing them with support, they were able to express their opinions in English. These kinds of activities are definitely helping my students to improve their writing, so I will continue to try them. [For more on supporting your students, see Resource 3.]

Activity 2: Try in the classroom – helping your students to write a longer text independently

This activity helps your students to write a longer text. You can use it with any class.

- Choose a writing task from your textbook or create a writing task. For example, you could choose a story or a summary of a story or lesson; a formal or informal letter; a report or an article for a newspaper or magazine; an application; a paragraph expressing an opinion about something; or perhaps a description.

- Before class, select one of the techniques described above to help your students undertake the writing task. Depending on the level of your students and the technique you have chosen, you will prepare a text with missing words, a model or a writing frame. You can write this on a large sheet of chart paper and stick it on the blackboard, or write it on the blackboard before class if possible.

- Ask your students to undertake the writing task using the resource you have prepared as a guide. As students work, move around the room to help where necessary. Give your students a time limit.

- When they are ready, ask two or three students to read out their work. The rest of the class should listen to see if they have written something similar or different. Ask other students for comments and additions.

Pause for thought Here are some questions for you to think about after trying this activity. If possible, discuss these questions with a colleague. After trying this activity with your students, consider the following questions:

|

Remember that writing in another language is difficult – there is so much to think about! Be positive and encouraging, and tell your students that they need to practise writing to learn how to write. If most of your students struggled, give them more support next time by giving them more of the language that they need, and help them with ideas about what to say. You can find more ideas for this in the unit Whole-class writing routines.

4 Managing the correction of your students’ written work

When students write independently, they will make more mistakes than when they are copying or reproducing memorised texts. You may feel that this means that your students are not performing so well. However, making mistakes is a natural part of the language learning process and is a sign that your students are learning and internalising the language. You can use these mistakes as an opportunity to support your students’ language learning.

Giving students positive and encouraging feedback on their writing can help them to learn and improve. You may think that it is difficult to correct all of your students’ written work, especially if you have a large class. You may feel that there is just not enough time to look at each student’s work or there are just too many different mistakes to deal with. These are common problems that teachers face, whatever level of students they teach. There are, however, ways in which you can make correcting students’ work easier:

- Remember that you don’t have to check each student’s work every time they write. You can choose to correct and review some students some of the time. Over a period of time, you will have the chance to correct and review each student’s work. Keep records of your students’ work for assessment purposes.

- If the writing exercises are simple (for example, short answers to comprehension questions or grammar exercises), you can write the correct answers on the blackboard or read them out and students can correct their own work or their neighbour’s. This gives them a better sense of their own writing and where they might need to improve.

- Get your students to do writing activities in pairs of groups sometimes. This means students can share their ideas, and help each other. They can write a text together, which means that there is less for you to correct.

- While each student is different and may need more or less support, there may be mistakes that are common to your group of students – you can focus on these to help them progress. As students are writing, walk around the room and note common, general mistakes. Write some sentences containing mistakes on the blackboard (without mentioning names) and ask your students to spot the mistakes and correct them.

- Concentrate on just some mistakes – perhaps one time focusing on tenses and another time on punctuation or grammar. You can decide based on what you think is a priority. Tell your students what you are focusing on – if they spot other mistakes to correct, that is fine. Make sure they realise that you are not ignoring mistakes.

- Get your students to keep a list of the mistakes that they make repeatedly in their notebooks. They can then refer to this list whenever they write. This helps students become more independent and have a better sense of what they need to improve. It can also act as a quick ‘checklist’ of things that they need to focus more on to improve their writing.

- Have a positive attitude towards mistakes and foster this among your students. Don’t chastise students for making mistakes. Remember that it is normal for students to make mistakes as they write in a new language, and mistakes show that they are learning. Remind your students that everyone makes mistakes sometimes – you included!

- Encourage your students to write independently as much as possible – and help them to enjoy it. They may enjoy writing more if they see that it can help them in life beyond school, and if they are encouraged to express their own ideas. If they can see the value of writing in English, it will motivate them to practise more and to learn more in the process.

Activity 3: Correcting your students’ written work

You can use a variety of techniques to manage how you correct your students’ written work. Use a form like Table 1 below to plan how you are going to do it over the next month. Remember to think about strategies for how to take the feedback forward so that it focuses on how the students can improve.

| Class and chapter: | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Week | Written work to be corrected | How will I correct it? | Whose work will I correct? | How to take it forward |

| 1 | ||||

| 2 | ||||

| 3 | ||||

| 4 | ||||

Table 2 shows an example of a completed form.

| Class and chapter: | Class X, Beehive Chapter 5, ‘The Snake and the Mirror’ | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Week | Written work to be corrected | How will I correct it? | Whose work will I correct? | How to take it forward |

| 1 | Answering questions about the lesson Students write answers in pairs |

Move around the room as students write and correct as many as possible Review correct answers with the whole class |

I haven’t seen students at the back of the room for a while – I will look at their work | Give extra support to students who seem to be struggling |

| 2 | Grammar exercise on reported speech | Write the correct answers on the blackboard Students correct their own work |

Students get a sense of whether they need more work in this area Suggest further practice for those who need it |

|

| 3 | Pair dictation | Students use the textbook to correct each other’s work | Students take note of spelling errors to work on | |

| 4 | Writing a story based on a picture Students write stories in pairs |

Take stories from ten pairs and correct them |

Names: Raju, Nimisha, Abdul, Aliya, Neelam, Brajesh, Suman, Ashraf, Ravinder, Rina |

Students had problems with past tense Review in next class |

Pause for thought After you have followed your plan for a month, answer these questions:

|

It is useful to make plans like these so that you know when your students are going to do written work, and that you are able to review the work of different students. Over the months, you will review the work of all your students and track their progress. In this way both you and they will get a better sense of their strengths and areas for improvement, and you will be able to see where you need to focus your teaching. See the unit Supporting language learning through formative assessment for information about correcting written work, giving feedback and using it for assessment purposes.

If your plan hasn’t worked out the way you had hoped it would, make another one and try some different techniques – see what works best for you and your class. The important thing is to keep trying to give your students as much positive and encouraging feedback as you can so that they can continue to improve.

5 Summary

You can help your students to move from copying and memorising texts to writing their own answers and compositions. You can help them to compose their own answers to comprehension questions by:

- giving them time to think about their answers

- encouraging them to work in groups to discuss and compose their responses

- providing models and writing frames that they can adapt according to their abilities and confidence.

They will make more mistakes as they write using their own words, but this is part of the learning process. You can use different strategies to manage the written work of your students and use their mistakes as opportunities to learn.

Over time and with practice, your students will develop the confidence and skills they need to write texts in English independently.

If you would like to develop your own writing skills in English, see Resource 4. If you are interested in reading more about teaching writing, see the additional resources section.

Other Secondary English teacher development units on this topic are:

- Helping students to develop their writing skills: You can learn more about helping students to write longer texts in this unit, and how to help them to develop their writing skills.

- Supporting language learning through formative assessment: You can learn about giving feedback on and assessing written work in this unit.

Resources

Resource 1: Using groupwork

Groupwork is a systematic, active, pedagogical strategy that encourages small groups of students to work together for the achievement of a common goal. These small groups promote more active and more effective learning through structured activities.

The benefits of groupwork

Groupwork can be a very effective way of motivating your students to learn by encouraging them to think, communicate, exchange ideas and thoughts, and make decisions. Your students can both teach and learn from others: a powerful and active form of learning.

Groupwork is more than students sitting in groups; it involves working on and contributing to a shared learning task with a clear objective. You need to be clear about why you are using groupwork for learning and know why this is preferable to lecturing, pair work or to students working on their own. Thus groupwork has to be well-planned and purposeful.

Planning groupwork

When and how you use groupwork will depend on what learning you want to achieve by the end of the lesson. You can include groupwork at the start, the end or midway through the lesson, but you will need to allow enough time. You will need to think about the task that you want your students to complete and the best way to organise the groups.

As a teacher, you can ensure that groupwork is successful if you plan in advance:

- the goals and expected outcomes of the group activity

- the time allocated to the activity, including any feedback or summary task

- how to split the groups (how many groups, how many students in each group, criteria for groups)

- how to organise the groups (role of different group members, time required, materials, recording and reporting)

- how any assessment will be undertaken and recorded (take care to distinguish individual assessments from group assessments)

- how you will monitor the groups’ activities.

Groupwork tasks

The task that you ask your students to complete depends on what you what them to learn. By taking part in groupwork, they will learn skills such as listening to each other, explaining their ideas and working cooperatively. However, the main aim is for them to learn something about the subject that you are teaching. Some examples of tasks could include the following:

- Presentations: Students work in groups to prepare a presentation for the rest of the class. This works best if each group has a different aspect of the topic, so they are motivated to listen to each other rather than listening to the same topic several times. Be very strict about the time that each group has to present and decide on a set of criteria for a good presentation. Write these on the board before the lesson. Students can the use the criteria to plan their presentation and assess each other’s work. The criteria could include:

- Was the presentation clear?

- Was the presentation well-structured?

- Did I learn something from the presentation?

- Did the presentation make me think?

- Problem solving: Students work in groups to solve a problem or a series of problems. This could include conducting an experiment in science, solving problems in mathematics, analysing a story or poem in English, or analysing evidence in history.

- Creating an artefact or product: Students work in groups to develop a story, a piece of drama, a piece of music, a model to explain a concept, a news report on an issue or a poster to summarise information or explain a concept. Giving groups five minutes at the start of a new topic to create a brainstorm or mind map will tell you a great deal about what they already know, and will help you pitch the lesson at an appropriate level.

- Differentiated tasks: Groupwork is an opportunity to allow students of different ages or attainment levels to work together on an appropriate task. Higher attainers can benefit from the opportunity to explain the work, whereas lower attainers may find it easier to ask questions in a group than in a class, and will learn from their classmates.

- Discussion: Students consider an issue and come to a conclusion. This may require quite a bit of preparation on your part in order to make sure that the students have enough knowledge to consider different options, but organising a discussion or debate can be very rewarding for both you and them.

Organising groups

Groups of four to eight are ideal but this will depend on the size of your class, the physical environment and furniture, and the attainment and age range of your class. Ideally everyone in a group needs to see each other, talk without shouting and contribute to the group’s outcome.

- Decide how and why you will divide students into groups; for example, you may divide groups by friendship, interest or by similar or mixed attainment. Experiment with different ways and review what works best with each class.

- Plan any roles you will give to group members (for example, note taker, spokesperson, time keeper or collector of equipment), and how you will make this clear.

Managing groupwork

You can set up routines and rules to manage good groupwork. When you use groupwork regularly, students will know what you expect and find it enjoyable. Initially it is a good idea to work with your class to identify the benefits of working together in teams and groups. You should discuss what makes good groupwork behaviour and possibly generate a list of ‘rules’ that might be displayed; for example, ‘Respect for each other’, ‘Listening’, ‘Helping each other’, ‘Trying more than one idea’, etc.

It is important to give clear verbal instructions about the groupwork that can also be written on the blackboard for reference. You need to:

- direct your students to the groups they will work in according to your plan, perhaps designating areas in the classroom where they will work or giving instructions about moving any furniture or school bags

- be very clear about the task and write it on the board in short instructions or pictures. Allow your students to ask questions before you start.

During the lesson, move around to observe and check how the groups are doing. Offer advice where needed if they are deviating from the task or getting stuck.

You might want to change the groups during the task. Here are two techniques to try when you are feeling confident about groupwork – they are particularly helpful when managing a large class:

- ‘Expert groups’: Give each group a different task, such as researching one way of generating electricity or developing a character for a drama. After a suitable time, re-organise the groups so that each new group is made up of one ‘expert’ from all the original groups. Then give them a task that involves collating knowledge from all the experts, such as deciding on what sort of power station to build or preparing a piece of drama.

- ‘Envoys’: If the task involves creating something or solving a problem, after a while, ask each group to send an envoy to another group. They could compare ideas or solutions to the problem and then report back to their own group. In this way, groups can learn from each other.

At the end of the task, summarise what has been learnt and correct any misunderstandings that you have seen. You may want to hear feedback from each group, or ask just one or two groups who you think have some good ideas. Keep students’ reporting brief and encourage them to offer feedback on work from other groups by identifying what has been done well, what was interesting and what might be developed further.

Even if you want to adopt groupwork in your classroom, you may at times find it difficult to organise because some students:

- are resistant to active learning and do not engage

- are dominant

- do not participate due to poor interpersonal skills or lack of confidence.

To become effective at managing groupwork it is important to reflect on all the above points, in addition to considering how far the learning outcomes were met and how well your students responded (did they all benefit?). Consider and carefully plan any adjustments you might make to the group task, resources, timings or composition of the groups.

Research suggests that learning in groups need not be used all the time to have positive effects on student achievement, so you should not feel obliged to use it in every lesson. You might want to consider using groupwork as a supplemental technique, for example as a break between a topic change or a jump-start for class discussion. It can also be used as an ice-breaker or to introduce experiential learning activities and problem solving exercises into the classroom, or to review topics.

Resource 2: Sample writing frame of a letter that you can use to help your students write independently

To

The Headmistress,

D.D.B. Girls’ High School,

GolaghatDate: 1st June, 2014

Subject: Request for leave of absence

Madam,

I would like to inform you that I could not attend my classes on 28th and 29th May, 2014 because I was suffering from fever. A medical certificate is enclosed with this application for your consideration.

I hope you will kindly grant me leave of absence for these two days.

Yours faithfully,

Barsha Dutta

Roll No. 32

Class IX A

Resource 3: Monitoring and giving feedback

Improving students’ performance involves constantly monitoring and responding to them, so that they know what is expected of them and they get feedback after completing tasks. They can improve their performance through your constructive feedback.

Monitoring

Effective teachers monitor their students most of the time. Generally, most teachers monitor their students’ work by listening and observing what they do in class. Monitoring students’ progress is critical because it helps them to:

- achieve higher grades

- be more aware of their performance and more responsible for their learning

- improve their learning

- predict achievement on state and local standardised tests.

It will also help you as a teacher to decide:

- when to ask a question or give a prompt

- when to praise

- whether to challenge

- how to include different groups of students in a task

- what to do about mistakes.

Students improve most when they are given clear and prompt feedback on their progress. Using monitoring will enable you to give regular feedback, letting your students know how they are doing and what else they need to do to advance their learning.

One of the challenges you will face is helping students to set their own learning targets, also known as self-monitoring. Students, especially struggling ones, are not used to having ownership of their own learning. But you can help any student to set their own targets or goals for a project, plan out their work and set deadlines, and self- monitor their progress. Practising the process and mastering the skill of self-monitoring will serve them well in school and throughout their lives.

Listening to and observing students

Most of the time, listening to and observing students is done naturally by teachers; it is a simple monitoring tool. For example, you may:

- listen to your students reading aloud

- listen to discussions in pair or groupwork

- observe students using resources outdoors or in the classroom

- observe the body language of groups as they work.

Make sure that the observations you collect are true evidence of student learning or progress. Only document what you can see, hear, justify or count.

As students work, move around the classroom in order to make brief observation notes. You can use a class list to record which students need more help, and also to note any emerging misunderstandings. You can use these observations and notes to give feedback to the whole class or prompt and encourage groups or individuals.

Giving feedback

Feedback is information that you give to a student about how they have performed in relation to a stated goal or expected outcome. Effective feedback provides the student with:

- information about what happened

- an evaluation of how well the action or task was performed

- guidance as to how their performance can be improved.

When you give feedback to each student, it should help them to know:

- what they can actually do

- what they cannot do yet

- how their work compares with that of others

- how they can improve.

It is important to remember that effective feedback helps students. You do not want to inhibit learning because your feedback is unclear or unfair. Effective feedback is:

- focused on the task being undertaken and the learning that the student needs to do

- clear and honest, telling the student what is good about their learning as well as what requires improvement

- actionable, telling the student to do something that they are able to do

- given in appropriate language that the student can understand

- given at the right time – if it’s given too soon, the student will think ‘I was just going to do that!’; too late, and the student’s focus will have moved elsewhere and they will not want to go back and do what is asked.

Whether feedback is spoken or written in the students’ workbooks, it becomes more effective if it follows the guidelines given below.

Using praise and positive language

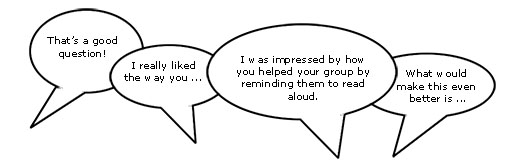

When we are praised and encouraged, we generally feel a great deal better than when we are criticised or corrected. Reinforcement and positive language is motivating for the whole class and for individuals of all ages. Remember that praise must be specific and targeted on the work done rather than about the student themselves, otherwise it will not help the student progress. ‘Well done’ is non-specific, so it is better to say one of the following:

Using prompting as well as correction

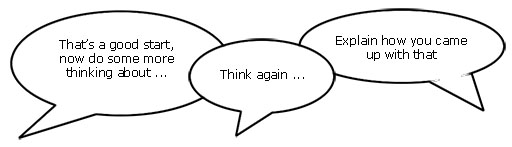

The dialogue that you have with your students helps their learning. If you tell them that an answer is incorrect and finish the dialogue there, you miss the opportunity to help them to keep thinking and trying for themselves. If you give students a hint or ask them a further question, you prompt them to think more deeply and encourage them to find answers and take responsibility for their own learning. For example, you can encourage a better answer or prompt a different angle on a problem by saying such things as:

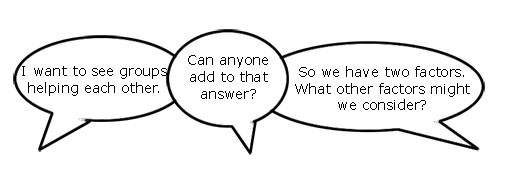

It may be appropriate to encourage other students to help each other. You can do this by opening your questions to the rest of the class with such comments as:

Correcting students with a ‘yes’ or ‘no’ might be appropriate to tasks such as spelling or number practice, but even here you can prompt students to look for emerging patterns in their answers, make connections with similar answers or open a discussion about why a certain answer is incorrect.

Self-correction and peer correction is effective and you can encourage this by asking students to check their own and each other’s work while doing tasks or assignments in pairs. It is best to focus on one aspect to correct at a time so that there is not too much confusing information.

Resource 4: Develop your own English

Here are some tips for developing your own writing skills:

- Read as much as you can in English. Good writers are often also good readers! Reading as much as possible will help you to develop your vocabulary and language use.

- Write as much as you can in English – shopping lists, diaries, notes – whatever you can. This will help you develop confidence in writing, and will develop your fluency.

- Remember that you can take your time when you write something. You can write as many drafts as you like, and you can revise and edit your own work.

And don’t forget to share your written work with your peers. It’s always a good idea to get feedback.

Additional resources

- Articles on writing: http://www.teachingenglish.org.uk/ articles/ writing

- ‘Writing matters: getting started’ by Adrian Tennant: http://www.onestopenglish.com/ skills/ writing/ writing-matters/ writing-matters-getting-started/ 154745.article

- ‘Effective writing across the curriculum’: http://orelt.col.org/ module/ unit/ 4-effective-writing-across-curriculum

References

Acknowledgements

This content is made available under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike licence (http://creativecommons.org/ licenses/ by-sa/ 3.0/), unless identified otherwise. The licence excludes the use of the TESS-India, OU and UKAID logos, which may only be used unadapted within the TESS-India project.

Every effort has been made to contact copyright owners. If any have been inadvertently overlooked the publishers will be pleased to make the necessary arrangements at the first opportunity.

Video (including video stills): thanks are extended to the teacher educators, headteachers, teachers and students across India who worked with The Open University in the productions.