Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Thursday, 5 February 2026, 5:30 AM

TI-AIE: Strategies for teaching vocabulary

What this unit is about

This unit is about how you can help your students to learn, use and remember English vocabulary. Many students struggle with the lessons in the textbook, even in Classes IX or X. They don’t understand many of the words, and even after they are translated, students can find it difficult to remember what they mean.

It has been found that students learn languages best when they experience it in context and use the language independently in speaking and writing. As the Position Paper of the National Focus Group on Teaching of English (National Council of Educational Research and Training, 2006) states:

Research has also shown us that greater gains accrue when language instruction moves away from the traditional approach of learning definitions of words (the dictionary approach) to an enriched approach, which encourages associations with other words and contexts (the encyclopaedia approach).

This means that translating a text word-for-word or memorising lists of words will not necessarily help students to learn new vocabulary that they can use when they speak and write in English. Students need to develop strategies to guess the meaning of new words when they encounter them. You can help them do this by:

- showing similarities to words they already know

- using pictures to help your students guess the meaning of words

- miming.

However, learning a new word or phrase once does not mean that the student will remember it and be able to use it. That is why students also need support in learning how to record new vocabulary and repeatedly review it. If students improve their knowledge of vocabulary, they can understand their lessons more easily and will write and speak better in English, which can also lead to them performing better in exams.

The techniques in this unit help your students to become independent language learners who are able to understand, record and learn new vocabulary by themselves.

As you try the activities in this unit, remember that:

- techniques may not work the first time you do them – think about what happened in the lesson, make adjustments and try again

- students may not understand what is happening when you try a new technique – explain it to them and make the purpose of the activity clear

- you can use the activities in this unit as part of your normal classes – they do not need to take up a whole class, or be extra work for your class or you.

Make your classroom an encouraging place to be; a place where you and your students can try things out without fear of criticism.

What you can learn in this unit

- How to help students understand unknown English vocabulary from the context.

- Ways to help students remember their English vocabulary, for example by using a vocabulary log.

- Effective use of dictionaries to help your students record and learn new vocabulary.

1 Helping students to understand unknown English vocabulary in lessons

Lessons in secondary English textbooks can be difficult for many students. One of the reasons for this is that they contain a lot of words and phrases that students don’t know. As a teacher, your role is to help your students understand these words without making them feel discouraged.

Activity 1: Introducing unknown words

This is an activity for you to do on your own or with a colleague.

Read this paragraph from ‘A Visit to Cambridge’ (a chapter from the NCERT Class VIII textbook Honeydew):

Cambridge was my metaphor for England, and it was strange that when I left it had become altogether something else, because I had met Stephen Hawking there. It was on a walking tour through Cambridge that the guide mentioned Stephen Hawking, ‘poor man, who is quite disabled now, though he is a worthy successor to Issac Newton, whose Chair he has at the university.’ And I started, because I had quite forgotten that this most brilliant and completely paralysed astrophysicist, the author of A Brief History of Time, one of the biggest bestsellers ever, lived here.

Now answer the questions below. If you can, discuss them with a colleague:

- Do you think that this Class VIII text would be easy for your secondary English students to read?

- Which words do you think your students may not understand? Underline them or make a note of them in your notebook.

- How could you help your students to understand these words and this passage?

This passage might be quite difficult for some secondary English students to read, as it includes some difficult vocabulary and complicated grammatical structures. Depending on your students’ levels, some students will know the word ‘disabled’ while others won’t. Some might not understand the phrase ‘worthy successor’ or ‘completely paralysed’.

A simple way to help your students come to understand unknown words is to translate them into your home language. This can be useful, but there are also some disadvantages to translating:

- If you translate all the words in a passage, it will take a lot of time. Some students will get bored and lose interest in the text you are reading.

- Translating a piece of writing word-for-word doesn’t allow students to learn English phrases and groups of words that usually occur together.

- Translating something into home language helps students to understand what new vocabulary words mean, but it doesn’t always help them to remember those words and use them in their own speaking and writing.

- If students always rely on you to translate words, they will not develop strategies for understanding words when they are reading or listening to English by themselves.

In Activity 2 you will look at how you can help your students deal with new vocabulary in their lessons. This technique will help your students to understand the readings in the textbook and develop strategies for learning new vocabulary. They will also help students to become more independent, so that they will be able to learn by themselves outside the classroom or in their future lives.

Activity 2: Helping your students to understand unknown vocabulary in a lesson

This is an activity for you to try in your classroom. It helps students to guess the meaning of new vocabulary in a text that they are reading. It also helps them decide which words they should spend more time actively learning. You can use this activity with any lesson, and with students from any class or any ability as they can choose and learn different words.

- Choose a lesson from your textbook that contains vocabulary that you think your students don’t know. It could be the next lesson you will teach, including prose and poems. If the lesson is long, choose a few paragraphs or verses from it.

- Ask your students to read the lesson. They can read silently or aloud.

- While your students are reading, write a table like Table 1 on the blackboard. When they have finished, ask them to copy it into their notebooks.

| Words you don’t know but you can guess | Words you don’t know and you can’t guess |

|---|---|

- Before asking your students to do this activity on their own, ask the class for an example of a word for each column and fill it in. This way you can make sure that they understand what they need to do.

- Tell the students to note down words in the relevant columns. They should do this activity individually . Set a time limit for this (such as ten minutes) or ask for a maximum number of words (such as ten).

- When the time is up, ask the students to work with a partner and compare their answers in the first column. They should tell each other how they guessed the meaning.

- After a few minutes, stop the discussion . Now ask different pairs to share with the class the words they wrote in the first column and how they guessed the meaning. They can do this in their home language.

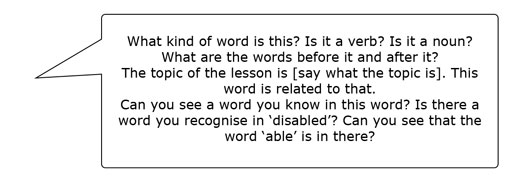

- Now ask students to read out the words that they couldn’t guess from the second column. Write these on the board and help them practise the pronunciation of these words by saying the words out loud and asking the class to repeat after you. Instead of providing the meaning or translation of these words, try to help your students guess the meaning.

- You can help them guess by asking questions like:

- Tell your students to choose ten words that they think are the most useful, and to learn them. You may want them to learn some additional specific words from the lesson. Write these additional words on the board, practise saying them with the class and discuss their meaning before telling students to add them to the list of words to learn.

Pause for thought Here are some questions for you to think about after trying this activity. If possible, discuss these questions with a colleague.

|

Students will get better at guessing the meanings of unknown words with practice. You should:

- encourage them to share how they guessed the meanings so that they can build up strategies

- help them to make connections between new vocabulary and words that they already know

- help them to recognise root words, prefixes and suffixes that help them to guess meanings (see Kinsella et al., undated).

It can also be useful to discuss what make words ‘useful’ with your class. Some words may be useful for exams, while others may be related to a topic or a subject that they are interested in.

You can find more ideas about how to help students guess the meaning of words from the context later in this unit. There are also additional vocabulary learning activities in Resource 1. Resource 2 includes examples of language that will help you do this kind of activity.

Case Study 1: Sunreet experiences a new way of understanding unknown words from a lesson in a textbook

Sunreet is a Class VIII student at a government upper primary school. He finds English difficult, and can’t understand many of the words in a lesson. His teacher recently used a new approach and he found that it helped him.

I missed a lot of classes in primary school and I find the English lessons in Class VIII difficult – and many of my classmates do too. My teacher tries her best to help us by reading the lessons aloud and translating them. This does help me to understand the lesson, but I don’t really remember many of the new words from the lesson.

Recently our teacher did something different in our English class. We had to read a lesson about an English scientist, Stephen Hawking [see Resource 3]. The teacher told us about him and then she asked us to read the first four paragraphs of the lesson silently. I have to say that I didn’t understand very much of the lesson when I read it. Then she asked us some questions about the lesson. I listened to the answers and learnt that the writer was a disabled person from India. So that was what ‘disabled’ meant!

Our teacher told us to write down words that we didn’t know and could guess, and words that we didn’t know and couldn’t guess. There were a lot of words that I didn’t know, like ‘metaphor’, ‘strange’ and ‘altogether’ – and I couldn’t guess very many. Then she told us to share our words in small groups, to see if we could help each other with the meanings. I felt a little embarrassed, because I had so many words, but my classmate helped me to understand some of them. And one of my friends showed me how he managed to guess the meaning of the word ‘bestseller’. He told me that the word described a book called A Brief History of Time, so it had to be a word related to the topic of books; and he realised that the word ‘seller’ came from the verb ‘to sell’. That made sense to me. I’d never really tried to guess a meaning of a word before.

After this, our teacher asked if there were any words that we didn’t know, and she explained them to us. She used lots of different ways to explain the words. For example, she tore a piece of paper into small bits to show us the meaning of the word ‘tear’. Then she told us to write down a list of ten words from the lesson to learn at home before the next class. I took them home and asked my older brother to help me. He’s in Class X and he tested me on the words. Next class, I could remember a lot of these words – especially ‘disabled’, ‘bestseller’ and ‘tear’ – and I felt proud.

2 Using different techniques to help students understand and learn new words

There are many ways that you can help students to understand new words. You can translate words, and you can ask students to guess meanings. At first, students may find it difficult to guess the meanings of words. You can show them how to guess meanings by using their existing knowledge of English, their understanding of the other words in the lesson, and their knowledge of the world. Read this sentence from ‘A Visit to Cambridge’ (see Resource 3):

There was his assistant on the line and I told him I had come in a wheelchair from India (perhaps he thought I had propelled myself all the way) to write about my travels in Britain.

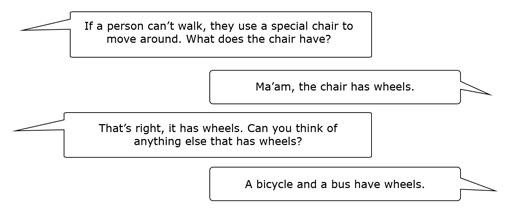

Students can guess the meaning of the word ‘wheelchair’ if they understand the words ‘wheel’ and ‘chair’, and by their knowledge of the world – they understand that a disabled person might use a wheelchair, and they may have seen one.

They can also make a good guess of the word ‘propelled’ once they understand the word ‘wheelchair’ and the topic of the lesson. They can see that it is a verb. It is used as part of the past perfect tense, and it has the ending ‘–ed’. When they know it is a verb, they can guess that it involves movement. By understanding how a person uses a wheelchair, they can guess the exact meaning of the word.

Pause for thought Can you think of any other ways that you could help students to understand the words ‘wheelchair’ and ‘propel’? If you can, discuss them with a colleague and note your ideas. |

Other ways that you can help students to understand new words include:

- Using a picture or a real object: You could draw a picture of a wheelchair on the board, use a picture from the textbook or cut out a picture from a magazine or newspaper.

- Using mime or gesture: You could mime a person propelling themselves in a wheelchair and ask students to say what the word is in their home language to check that they understand.

- Giving examples of the words in a different context and asking students to guess: For example, you could say: ‘The boat was propelled across the water by the wind.’

- Explaining what the word means in English: Ask questions to make sure that your students understand the meaning.

Remember that you don’t have to use all of these techniques each time your students need to know a new word! Different techniques suit different words; for example, it can be easy and quick to mime an action. See Resource 4, ‘Using questioning to promote thinking’, for more on using questions to involve students.

Activity 3: Using different techniques to help your students understand and learn new words

This is an activity for you to do in the classroom with your students.

Using a variety of techniques will help your students to understand new words, and it will also help them to remember them better. They might remember the picture that you drew on the board, or the enjoyable mime. Follow these steps and try some different techniques in your classroom:

- Choose a lesson from your textbook. It can be any lesson, including prose or poetry. It could even be the next one you teach. If the lesson is long, choose a few paragraphs or verses.

- Before the lesson, select some words that you think your students won’t know. If you are not familiar with some of the words, you might like to look them up in a dictionary. (See the additional resources section of this unit for links to online dictionaries.) Practise saying the words and phrases out loud so that students can repeat them after you.

- Decide how you could help your students understand these words. Could you draw or mime them? Can you think of some other examples of sentences using the word? How could you explain the word in English? What questions could you ask your students to check that they understand (for example: ‘What is the opposite of this word?’)

- Before your students read the lesson, write the words on the board.

- Ask your students if they know what the words mean. If they don’t know, help them to understand using the different techniques that you prepared. If they are having difficulty understanding, try another technique. Try to avoid using translation if possible; try to use it only as a last resort. See Resource 2 for some of the language you could use to teach vocabulary.

3 Helping your students to record and remember vocabulary

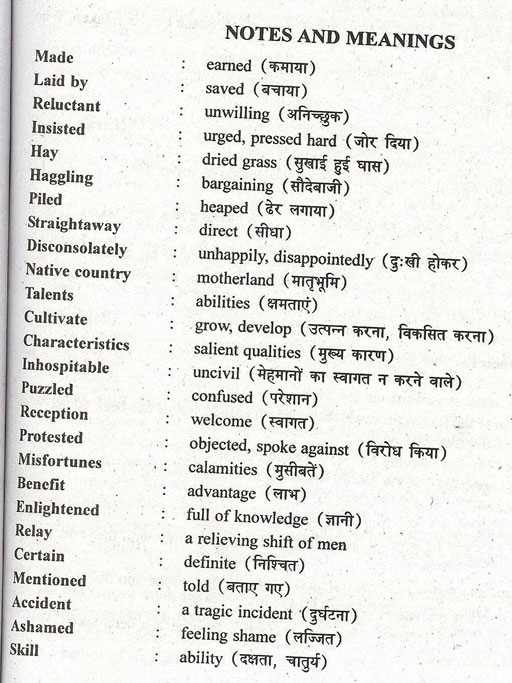

Many students use word lists to record and remember words. Word lists are also known as glossaries and you can find these at the end of many textbooks. Students can also create their own personalised glossaries, which they can keep up to date at the end of their notebooks as they learn new vocabulary words. An example glossary from a Class X textbook is shown in Figure 1.

Lists and glossaries can be useful for learning vocabulary. However, there are some disadvantages. Sometimes, a word list gives only translations, and doesn’t give other information about words. Information that can be useful when learning vocabulary includes:

- pronunciation

- grammar (such as the past participle of a verb, or whether it’s a noun, verb or adjective)

- the words it is typically used with (for example, the verb ‘mention’ is often followed by ‘that’; the word ‘ashamed’ is often followed by ‘about’)

- its formality (is it formal or informal?).

Also, some students may be able to memorise word lists, but others find it difficult. Even if students are able to remember the words from the list for a short while (for a test, for example), they may quickly forget them and probably won’t be able to use them in their own speaking and writing.

In order to develop their vocabulary so they can use it in their own speaking and writing, students need to see and hear words a number of times and have the opportunity to use the words. If students learn new words and then don’t see or use them again, they will soon forget them. Teachers need to include activities that give students the chance to review and use new words. You can find some ideas for other activities for developing students’ vocabulary in the additional resources section of this unit.

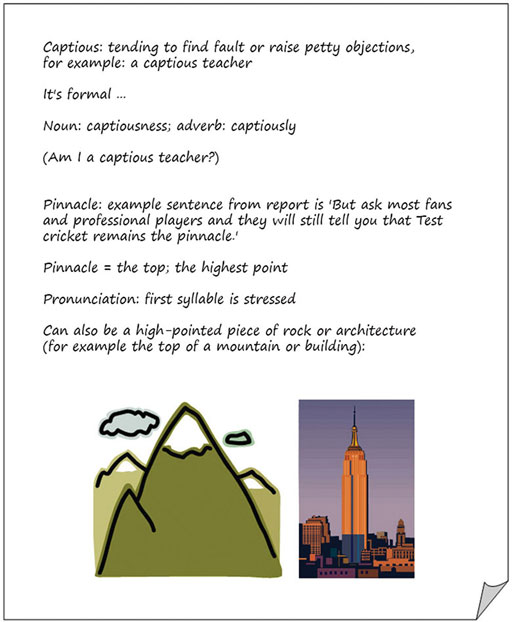

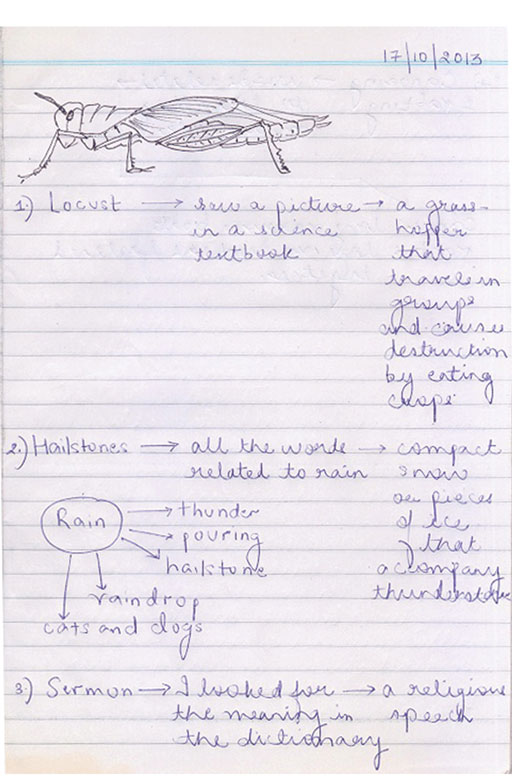

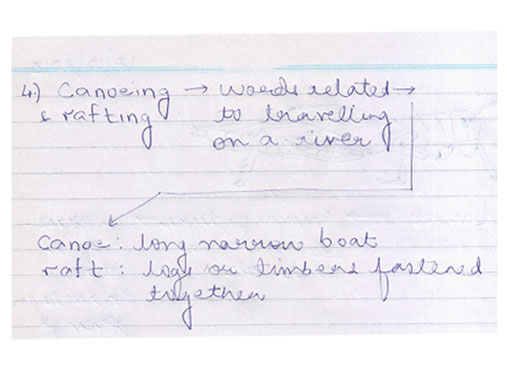

A useful way of helping students to record and remember words is by using a ‘vocabulary log’. This is a separate notebook where a student can:

- record new words, noting down information about the word

- note anything that would help them remember the word, for instance, where they first came across it

- copy or paste a picture

- add grammatical information about the word

- describe the word’s pronunciation or usage (such as whether it is formal or informal)

- note examples of the word used in a sentence (by copying it from the passage they read it in, for example)

- note related words.

Vocabulary logs are useful because they provide opportunities for students to review lessons and remember new words. Students can use vocabulary logs both inside and outside the classroom. By asking students to review their logs, or look at each other’s logs to see how much they remember, you are helping them to reflect on their own learning. This helps them to see the progress that they are making and to become independent learners.

Examples of vocabulary logs are shown in Resource 5.

Case Study 2: Mr Aparajeeta uses vocabulary logs with Class X to help students remember words

Mr Aparajeeta teaches English to Class X. He recently attended a teacher training session about teaching vocabulary. At the end of the session, teachers shared ideas about recording and remembering words, and one teacher mentioned ‘vocabulary logs’. Mr Aparajeeta decided to try this with his class.

I like the idea of the vocabulary logs very much. I kept one for a while myself when I was a student, and I found it very helpful. Of course, I am so busy nowadays and I’ve got out of the habit. But my students need to learn vocabulary for their exams, and they spend so much time memorising things … I wanted to see if keeping a vocabulary log would help them.

I asked each student to buy a small notebook and bring it to class. Some of the students didn’t bring a notebook so I gave them one (I bought a few before the class). I told the students that the notebooks were going to be their vocabulary logs – a place where they could note down new words. We discussed what they could include in the logs, and I put some examples on the board. At the end of the class, I asked them to look through the lesson and note down some words.

Now the class spends 20–30 minutes a week completing their vocabulary log. I tell students to look through the lessons and to write down new words that they need to or would like to remember. I let them work as they prefer. Some students like to work individually; others work in pairs or groups. They write down the words of their choice. I think it’s important for students to choose the words rather than me telling them which words to write down. If I choose the words, some of the students may already know them. And anyway, it encourages them to be responsible for their own learning, and this can only help them in the future when I’m not around.

I move around the room as they work to make sure that they are completing their vocabulary logs, but also to help and make suggestions. For instance, I give example sentences with the new words, or I give examples of related words or opposites, and I deal with any mistakes I see. It’s very interesting to see which words the students note down. It helps me to see which words the students know and don’t know, and which students need more or less help. I also take a few logs in to look at from time to time – not all of them, of course – there are just too many! This helps me to see the progress that my students are making in English, and I use this information as part of their assessment.

Every now and then I ask the students to take out their vocabulary logs and to test each other using the words. After all, there’s no point having a record of words if you don’t look at them! I know that some of the students look at them at home – and even add words – but others don’t, so I’m trying to find ways of encouraging them to look through the words. I know that it’s important to look at words again and again to remember them.

My students have now been keeping a vocabulary log for two months. I think they’re starting to lose enthusiasm, so I’ve decided that I’m going to have a competition at the end of term. I’m going to give a small prize to the student with the best vocabulary log. Hopefully, that will keep them more motivated!

Activity 4: Using vocabulary logs with your students

This is an activity for you to try with your students.

In Case Study 2, Mr Aparajeeta used vocabulary logs with a group of Class X students. Vocabulary logs are useful for recording and remembering vocabulary. They can also be a project that students can carry out over a term, or even a school year. The books could be evaluated and form part of the overall assessment of each student. Students of any level can keep a vocabulary log.

- Ask students to buy and bring in a cheap notebook to the next English class. Buy a few yourself in case some students are not able to buy a notebook.

- Tell students that the notebook will be their vocabulary log. They will use it to record vocabulary.

- Tell students to note down some words from this (or the last) lesson, and give some examples of what they can write in the notebook (such as a picture, an example sentence, grammatical information and so on). You could write the examples on the board.

- Give students time each week to note words in their logs, and encourage them to add words at home too. As they complete their logs, walk around and help where necessary.

- Take in different students’ logs from time to time and look through them. Make notes about the logs and use them as part of your continuous assessment of each student. You can also use the logs to plan your teaching: are there any areas of vocabulary that students are having problems with? Which students needs more help? How can you help them? (See the unit Supporting language learning through formative assessment for more information.)

Pause for thought Here are some questions for you to think about after trying this activity. If possible, discuss these questions with a colleague.

|

It is important to help students to stay enthusiastic about keeping vocabulary logs. Encourage students to complete their logs in and outside the classroom. Ask students to share their logs, and show students examples of logs that are more effective. Look at your students’ logs from time to time. You could even award a prize for the best logs, or the most words learned. Encourage students to use words from the logs in their own work, for example writing or speaking activities. Ask them to use some words from the log in different sentences. Remind students that learning words is more than knowing what they mean – they need to be able to use them too.

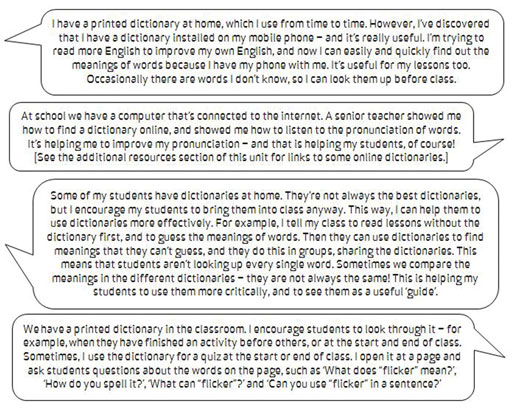

4 Using dictionaries effectively

Dictionaries are a useful resource for both you and your students. As you read and listen to English, you will come across words that you don’t know, or that you can’t guess the meanings of – after all, it’s not possible to know every word in English! A dictionary helps you – and your students – to understand what a word means, and some dictionaries give you a lot more information about a word. Read this entry from Collins COBUILD Learner’s Illustrated Dictionary for the word ‘propel’:

Propel/ prəˈpel/ (propels, propelling, propelled)

- To propel someone or something in a certain direction means to cause them or it to move in that direction. Rebecca took Steve’s elbow and propelled him towards the door.

- If something propels you into a particular activity, it causes you to be involved in it. It was this event which propelled her into politics.

Wordlink: pel = driving, forcing: compel, expel, propel

This entry tells you:

- how the word is pronounced

- how it is formed in different tenses

- different meanings of the word

- how it is used in sentences

- how it is related to other words.

Not all dictionaries give this information. Nonetheless, they are still very useful, as they give an idea of what words mean, and possibly how they are used. If students have access to a dictionary in the school, classroom or at home, they will be able to find out the meanings of words themselves and will be less dependent on you. That means you will have time to do other things in your English classes.

Activity 5: Planning to use dictionaries more effectively

Part A:

Note down your answers to these questions. If possible, share your answers with a colleague.

- Do you have a dictionary?

- If you do, what kind of a dictionary is it? How do you use it?

- If you don’t, is it possible to buy or share a dictionary, or access o on your mobile phone?

- Do your students have dictionaries?

- If so, do they bring them into the classroom?

- How do they use them? Do you encourage them to use them at home?

- Is there a dictionary in your school or classroom?

- If so, how do you use it?

- If there isn’t a dictionary available, could you buy a dictionary for the classroom? Or bring one into the classroom on your mobile phone? How could you use it?

Part B:

Now read some other teachers’ answers to these questions.

Part C:

How could you improve your use of dictionaries with your own students? Choose one of the activities above and try it yourself or with your class.

5 Summary

The lessons in English textbooks typically have many words that students don’t know. Translating the words is one technique that you can use, but there are some disadvantages to this. It is more useful to teach students techniques that will help them to understand the words themselves. In this unit you explored some ways to help your students work out the meaning of words and remember them. These are techniques that you can use with all the textbook lessons to help your students become more independent, confident learners.

If you would like some ideas for improving your own vocabulary in English and for phrases you can use to teach vocabulary, see Resource 2. If you would like to read more about teaching vocabulary, look at the additional resources section.

Resources

Resource 1: Activities that help students to remember new words

- Two Words, One Sentence: Students need to use words in order to learn about how the words work with other words, so this activity encourages the students to produce language. Write up two of the words you want to review on the board and put students into pairs or groups. Ask the students to produce a single sentence that includes both words. Get some of the students to tell you their sentences. Choose the best one and write it on the board for the students to copy, then repeat this process with two more words.

- Five-word Story: Draw a grid on the board with a collection of words that your students have recently started learning. Put the students into small groups and ask them to select five of the words. Once the groups have chosen five words each, tell them to create a very short story that includes all five words. Once they have created their stories, put students into pairs to share their stories or get someone from each group to tell the class their story.

- Three Meanings: This is a quick and useful way to use the glossaries in the textbook to revise vocabulary. Ask the students to shut their books. Write a word on the board, then read three definitions from the textbook glossary. Ask the students to guess which is the correct one. If you have the space in your classroom or outside the classroom, you can make this more fun and ask the students to stand up. If the first definition is correct, they go to the right side of the classroom; if the second is correct, they move to the centre of the classroom; and if the third is correct, they move to the left side.

- Word Bag: This is an ongoing activity that you can do throughout the school year. At the end of each chapter, give your students small slips of paper. Ask them to write words they need or want to learn on one side of the slip, and information about the word on the other side (such as a translation, example sentences, grammatical information and so on). At the end of the class, collect all the slips of paper and put them in a bag. Regularly take random words out of the bag and ask questions about them, such as ‘What does it mean?’ or ‘Give me an example sentence.’ These quick revision quizzes will help your students to remember words from lessons.

Resource 2: Develop your own English with language for teaching vocabulary

Here is some language you can use when teaching voacbulary:

- ‘Which words don’t you know? Can you please write down the words that you don’t understand?’

- ‘I’m sure you can guess the meaning of some of those words from the context.’

- ‘Which are the words you can guess the meaning of?’

- ‘That’s not exactly right. Any other guesses?’

- ‘Yes, spot on! How could you guess the meaning? What were the clues?’

- ‘Which are the words you couldn’t guess?’

- ‘What is the opposite of that word?’

- ‘Do you know a word that is similar to this?’

- ‘What kind of word is it? Is it a verb? Is it a noun?’

- ‘What are the words before it and after it?’

- ‘What is the topic of the lesson? Do you think this word is related to that topic?’

- ‘You already know the word “helper”. The word “assistant” is similar to that.’

- ‘Can you see another word inside of this word? Can you see that the word “assist” is in there?’

- ‘Do you know another word that is similar to this?’

- ‘What word can you recognise in “disabled’” Did you notice that the word “able” is in there?’

- ‘You know the word “able”, yes? Can you guess what “disabled”’ means?’

- ‘Okay, so which of these words do you think are important for you to remember?’

- ‘Circle the words that you think are important.’

- ‘You might need to know some of these words for the exam.’

Here are some tips for developing your own vocabulary in English:

- Read as much as you can in English (newspapers, magazines, books).

- Try to use strategies you have learned about in this unit, such as guessing words from the context and deciding which words are useful to learn.

- If possible, find out how new words are pronounced and learn how they are used.

- Keep a vocabulary log – note down new words and revisit it often.

- Keep a dictionary near you so that you can consult it whenever you need to.

- Play word games in English, such as crossword puzzles.

Here are some links to sites that are useful for developing vocabulary:

- ‘Grammar, vocabulary & pronunciation’: http://www.bbc.co.uk/ worldservice/ learningenglish/ language/

- ‘Vocabulary games’: http://learnenglish.britishcouncil.org/ en/ vocabulary-games

Resource 3: Using pair work

Cambridge was my metaphor for England, and it was strange that when I left it had become altogether something else, because I had met Stephen Hawking there.

It was on a walking tour through Cambridge that the guide mentioned Stephen Hawking, ‘poor man, who is quite disabled now, though he is a worthy successor to Issac Newton, whose Chair he has at the university.’ And I started, because I had quite forgotten that this most brilliant and completely paralysed astrophysicist, the author of A Brief History of Time, one of the biggest bestsellers ever, lived here.

When the walking tour was done, I rushed to a phone booth and, almost tearing the cord so it could reach me outside, phoned Stephen Hawking’s house. There was his assistant on the line and I told him I had come in a wheelchair from India (perhaps he thought I had propelled myself all the way) to write about my travels in Britain. I had to see Professor Hawking — even ten minutes would do. ‘Half an hour,’ he said. ‘From three-thirty to four.’

And suddenly I felt weak all over. Growing up disabled, you get fed up with people asking you to be brave, as if you have a courage account on which you are too lazy to draw a cheque. The only thing that makes you stronger is seeing somebody like you, achieving something huge. Then you know how much is possible and you reach out further than you ever thought you could.

Resource 4: Using questioning to promote thinking

Teachers question their students all the time; questions mean that teachers can help their students to learn, and learn more. On average, a teacher spends one-third of their time questioning students in one study (Hastings, 2003). Of the questions posed, 60 per cent recalled facts and 20 per cent were procedural (Hattie, 2012), with most answers being either right or wrong. But does simply asking questions that are either right or wrong promote learning?

There are many different types of questions that students can be asked. The responses and outcomes that the teacher wants dictates the type of question that the teacher should utilise. Teachers generally ask students questions in order to:

- guide students toward understanding when a new topic or material is introduced

- push students to do a greater share of their thinking

- remediate an error

- stretch students

- check for understanding.

Questioning is generally used to find out what students know, so it is important in assessing their progress. Questions can also be used to inspire, extend students’ thinking skills and develop enquiring minds. They can be divided into two broad categories:

- Lower-order questions, which involve the recall of facts and knowledge previously taught, often involving closed questions (a yes or no answer).

- Higher-order questions, which require more thinking. They may ask the students to put together information previously learnt to form an answer or to support an argument in a logical manner. Higher-order questions are often more open-ended.

Open-ended questions encourage students to think beyond textbook-based, literal answers, thus eliciting a range of responses. They also help the teacher to assess the students’ understanding of content.

Encouraging students to respond

Many teachers allow less than one second before requiring a response to a question and therefore often answer the question themselves or rephrase the question (Hastings, 2003). The students only have time to react – they do not have time to think! If you wait for a few seconds before expecting answers, the students will have time to think. This has a positive effect on students’ achievement. By waiting after posing a question, there is an increase in:

- the length of students’ responses

- the number of students offering responses

- the frequency of students’ questions

- the number of responses from less capable students

- positive interactions between students.

Your response matters

The more positively you receive all answers that are given, the more students will continue to think and try. There are many ways to ensure that wrong answers and misconceptions are corrected, and if one student has the wrong idea, you can be sure that many more have as well. You could try the following:

- Pick out the parts of the answers that are correct and ask the student in a supportive way to think a bit more about their answer. This encourages more active participation and helps your students to learn from their mistakes. The following comment shows how you might respond to an incorrect answer in a supportive way: ‘You were right about evaporation forming clouds, but I think we need to explore a bit more about what you said about rain. Can anyone else offer some ideas?’

- Write on the blackboard all the answers that the students give, and then ask the students to think about them all. What answers do they think are right? What might have led to another answer being given? This gives you an opportunity to understand the way that your students are thinking and also gives your students an unthreatening way to correct any misconceptions that they may have.

Value all responses by listening carefully and asking the student to explain further. If you ask for further explanation for all answers, right or wrong, students will often correct any mistakes for themselves, you will develop a thinking classroom and you will really knowwhat learning your students have done and how to proceed. If wrong answers result in humiliation or punishment, then your students will stop trying for fear of further embarrassment or ridicule.

Improving the quality of responses

It is important that you try to adopt a sequence of questioning that doesn’t end with the right answer. Right answers should be rewarded with follow-up questions that extend the knowledge and provide students with an opportunity to engage with the teacher. You can do this by asking for:

- a how or a why

- another way to answer

- a better word

- evidence to substantiate an answer

- integration of a related skill

- application of the same skill or logic in a new setting.

Helping students to think more deeply about (and therefore improve the quality of) their answer is a crucial part of your role. The following skills will help students achieve more:

- Prompting requires appropriate hints to be given – ones that help students develop and improve their answers. You might first choose to say what is right in the answer and then offer information, further questions and other clues. (‘So what would happen if you added a weight to the end of your paper aeroplane?’)

- Probing is about trying to find out more, helping students to clarify what they are trying to say to improve a disorganised answer or one that is partly right. (‘So what more can you tell me about how this fits together?’)

- Refocusing is about building on correct answers to link students’ knowledge to the knowledge that they have previously learnt. This broadens their understanding. (‘What you have said is correct, but how does it link with what we were looking at last week in our local environment topic?’)

- Sequencing questions means asking questions in an order designed to extend thinking. Questions should lead students to summarise, compare, explain or analyse. Prepare questions that stretch students, but do not challenge them so far that they lose the meaning of the questions. (‘Explain how you overcame your earlier problem. What difference did that make? What do you think you need to tackle next?’)

- Listening enables you to not just look for the answer you are expecting, but to alert you to unusual or innovative answers that you may not have expected. It also shows that you value the students’ thinking and therefore they are more likely to give thoughtful responses. Such answers could highlight misconceptions that need correcting, or they may show a new approach that you had not considered. (‘I hadn’t thought of that. Tell me more about why you think that way.’)

As a teacher, you need to ask questions that inspire and challenge if you are to generate interesting and inventive answers from your students. You need to give them time to think and you will be amazed how much your students know and how well you can help them progress their learning.

Remember, questioning is not about what the teacher knows, but about what the students know. It is important to remember that you should never answer your own questions! After all, if the students know you will give them the answers after a few seconds of silence, what is their incentive to answer?

Resource 5: Examples of vocabulary logs

Additional resources

Some articles and activities about vocabulary:

- ‘Vocabulary teaching: effective methodologies’ by Naveen Kumar Mehta: http://iteslj.org/ Techniques/ Mehta-Vocabulary.html

- ‘Strategies for vocabulary development’ by Kate Kinsella, Colleen Shea Stump and Kevin Feldman: http://www.phschool.com/ eteach/ language_arts/ 2002_03/ essay.html

- Articles on vocabulary: http://www.teachingenglish.org.uk/ articles/ vocabulary

- Vocabulary activities: http://www.teachingenglish.org.uk/ search/ apachesolr_search/ vocabulary%20activities

Some online dictionaries:

- Collins – English for Learners: http://www.collinsdictionary.com/ dictionary/ english-cobuild-learners

- Cambridge Dictionaries Online: http://dictionary.cambridge.org/

- Oxford Dictionaries: http://www.oxforddictionaries.com/

References

Acknowledgements

This content is made available under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike licence (http://creativecommons.org/ licenses/ by-sa/ 3.0/), unless identified otherwise. The licence excludes the use of the TESS-India, OU and UKAID logos, which may only be used unadapted within the TESS-India project.

Every effort has been made to contact copyright owners. If any have been inadvertently overlooked the publishers will be pleased to make the necessary arrangements at the first opportunity.

Video (including video stills): thanks are extended to the teacher educators, headteachers, teachers and students across India who worked with The Open University in the productions.