Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Thursday, 5 February 2026, 7:35 AM

TI-AIE: Whole-class writing routines

What this unit is about

This unit is about helping your students to develop their writing skills so that they can write better compositions. At secondary level, students are expected to compose a variety of texts such as stories, letters and applications, reports, and articles. Many students struggle with this. There could be many reasons for this – for example , that they:

- don’t have many ideas about what to write

- find it difficult to organise their ideas logically

- make a lot of language mistakes.

This unit shows you some techniques that you can use in your classroom to help your students write better compositions in English. It describes how you can help your students to generate ideas, plan and write first drafts, and review their work. This will help them to develop their writing skills and become better writers in any language.

What you can learn in this unit

- How to use brainstorming in your lessons.

- How to use pair work to help students to plan and write a first draft.

- How to use peer reviews to improve written work.

1 Generating ideas for writing

Writing in another language is difficult. When students write in English, they have to think about things like grammar and vocabulary, using the correct punctuation, and spelling. When writing at school, your students are probably worried about making mistakes and getting low grades. Of course, these are important, but there is more to writing than these aspects.

When you write something, you want to communicate something to your reader. The reader might be yourself (for example, if you have written some notes on something you have read, or if you have written a shopping list), or somebody else (your headteacher reading an application that you have written is one example). In composing the text, you might have considered how best to organise your messages. You might even have written more than one draft or asked somebody to check your work – especially if the text is about something important or will be made public.

Effective writers think about the language that they are using but they also think about what they want to say and the potential reader or readers of what they write. They think about how to organise their points logically so that what they have written is clear – and, hopefully, interesting. They review their work and perhaps write more than one draft; they may also ask others to review their work before writing a final draft.

You can help your students to develop the skills of effective writing. This will help them to write better English compositions that have the ideas logically organised, are interesting to read and are more accurate. These skills will also be useful for writing in other languages. The process of organising ideas, reviewing work and writing drafts will make them more effective writers in general.

One of the problems that a writer in any language has is knowing what to say. This can be particularly difficult when writing in English. Sometimes the topics in the textbook are difficult; sometimes students don’t have the language they need to write about these topics.

Pause for thought Imagine that your students have to write a composition with the title ‘Pollution’. What problems do you think they might have? |

Read what this student is thinking:

With a topic such as pollution, students may not know much about it – and even if they do, they may not have the language skills to be able to write about it in English. This means that they may struggle to write more than one or two lines.

Pause for thought Think about these questions and, if possible, discuss them with a colleague:

|

One technique that you could use to generate ideas and language is brainstorming. This involves giving students a prompt – for example, the word ‘pollution’ written on the blackboard, or pictures from a newspaper of a polluted river or city – and then collecting ideas from your students relating to the word or picture. You can write the students’ ideas on the blackboard, or your class can work in groups, with one student noting down all the ideas in their notebooks or on chart paper. Encourage students to use their imagination and to suggest as many words and ideas as they can.

Once your students have contributed their ideas, they need to discuss and decide which ideas to keep. You can do this with the whole class, or if students are working in groups, the group members can do this together.

Brainstorming is a helpful technique to use in the classroom because it:

- generates ideas for content so that students will know what to write (or speak) about

- generates key words and phrases that they can use when they write (or speak)

- helps students who need more support

- helps you to see what your students remember from previous lessons and what they already know

- encourages students to share and learn from each other

- develops creativity

- encourages less confident students to contribute ideas without them being exposed to one-to-one questioning where the whole class is waiting for their response.

See Resource 1, ‘Talk for learning’, for more on brainstorming and value of getting students talking.

Case Study 1: Mrs Bhatia tries a brainstorming session in her English class

Mrs Bhatia teaches English to Class IX. The Hindi teacher at her school told her about brainstorming, and Mrs Bhatia tried it with her students.

I decided to try a brainstorming session with the writing task in the chapter we were studying. [Chapter 8 of the NCERT Class IX textbook Beehive – see Resource 2 for the complete text.] The writing task had the following instructions:

Working in pairs, go through the table below that gives you information about the top women tennis players since 1975. Write a short article for your school magazine comparing and contrasting the players in terms of their duration at the top. Mention some qualities that you think may be responsible for their brief or long stay at the top spot.

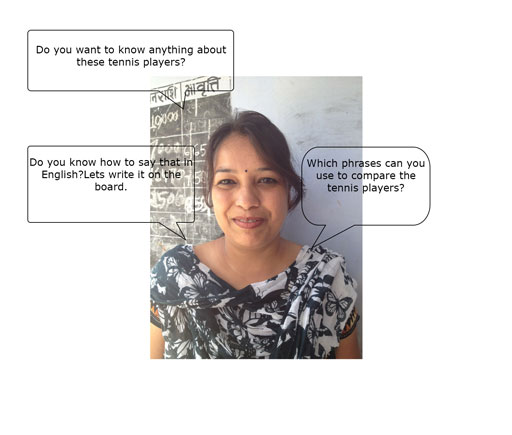

Once my students had read the instructions, I asked them a few questions to generate some ideas about the qualities of a successful tennis player, and some language for the writing task.

I told my students they could speak in their home languages if they needed to, and as they gave suggestions for words and expressions, I wrote them in English on the board. Some students made suggestions in English, and they often made mistakes; for example, one student said ‘shorter as’ instead of ‘shorter than’. I didn’t correct him, though – I just said it correctly in English and wrote the correct version on the board. The most important thing was to get ideas, and if I corrected everyone when they spoke, they would feel discouraged.

As I wrote words and phrases on the board, I read them out so that students could hear the pronunciation of any new vocabulary, and I checked that students understood the meanings. I also organised the words and ideas into different sub-topics such as ‘qualities’ and ‘phrases for comparing’ as I wrote. Sometimes, students made suggestions that were not very useful. Kalika suggested ‘nervous’ as a quality. I wrote it on the board anyway. Once all of the ideas were on the board, we discussed them and decided to reject a few of the words and phrases (including the word ‘nervous’).

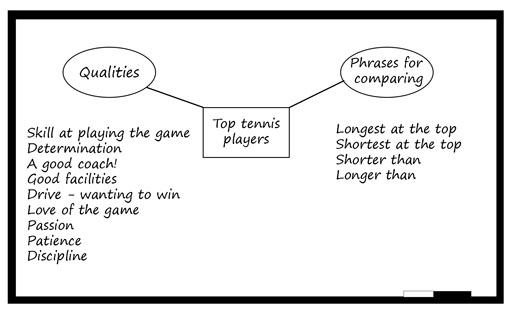

At the end of the brainstorming session, this is what my board looked like:

I organised my students into pairs, and asked them to do the writing task. I know that some teachers worry about students doing writing activities in pairs – they feel that the weaker students may simply copy from the stronger ones. I find this can sometimes happen, but when students work in pairs they are able to generate even more ideas, and are able to discuss how to use the language written on the board. In this way, everyone benefits.

When the class finished, I took in some of my students’ written work to look over. I was happy to see that the students had written more than usual, and that they used the new language well.

I will try this again the next time there is a writing task in the textbook. Next time, however, I will ask my students to brainstorm their ideas in groups first. This will encourage more students to contribute to the activity.

Activity 1: Try in the classroom – using brainstorming for a writing task

You can use brainstorming with any class, and with many different writing tasks from the textbook. Follow these steps to try it with your students:

- Before the lesson begins, choose a writing task from your textbook or a topic that your students have to write about in exams (such as ‘My favourite festival’ or ‘My favourite leader’).

- Imagine that you have to write this composition. Which words and phrases are useful? Write them down. Write down the questions that you will ask your students around the topic to help them generate ideas. This prepares you for the lesson.

- In class, write the topic title in the centre of the blackboard (such as ‘My favourite leader’), or tell your students to read the instructions for the writing task in their textbooks.

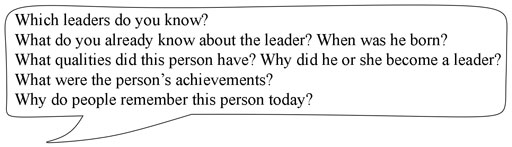

- Ask some questions to generate ideas about the topic. Encourage different students to contribute ideas. If your students are finding it difficult to think of ideas in English, let them use another language and then ask other students to translate. As they generate ideas, write them on the board. If they struggle, you might ask some prompt questions – but only as a last resort, because brainstorming is about valuing and capturing students’ ideas. Some example questions for ‘My favourite leader’ are:

- When students have finished suggesting ideas, you should have a lot of words on the board. At this stage, discuss how students might organise their ideas. Which words and phrases belong together? Which ideas might come first?

- Tell your students to write about the topic, and set a time limit. They could work individually or in pairs.

Pause for thought Here are some questions for you to think about after trying this activity. If possible, discuss these questions with a colleague.

|

It can be difficult for students to contribute at first, and you may find that one or two students dominate. If this is the case, you can put students into groups and give them some time (for example, five minutes) to discuss ideas, words and phrases.

An alternative to using the brainstorming technique is to announce the topic a week or two in advance so that everyone has the chance to think about and research it. Then when you ask for ideas from the class, most students will be able to contribute.

2 Making text writing meaningful

Before they write, students need time to organise their ideas and information. They can do this by making notes in their notebook, maybe moving ideas around as they work.

As students plan their written work, it is important that they know the kind of text that they are writing and who their potential readers are.

It can be very useful to get students to share ideas and plan in pairs because it:

- gives students confidence in their ability to write

- helps students to develop writing and language skills

- enables students to learn from each other

- ensures everyone’s participation.

Case Study 2: Using pair work in writing

Mrs Jadhev teaches English to Class IX. Her students were practising writing a letter of invitation. First of all, she asked for ideas to start all students thinking about invitation letters.

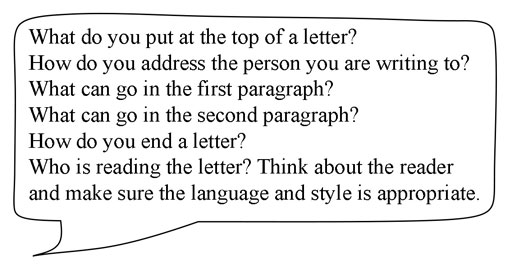

Students shared their ideas and I wrote them on the board. Then I asked them some questions about letters, and how they are usually structured.

I then told students to decide which letter of invitation they wanted to write using the ideas they had suggested (for example, inviting a friend to a brother’s wedding), and to make some notes about what they wanted to include in the letter, and how they were going to organise it. I gave them ten minutes to do this.

After this, I asked my students to work together in pairs and to share and discuss their preliminary notes. I encouraged students to add to or delete from what they had written, and to discuss how the letter was organised.

There was a buzz in the class as students discussed their ideas with each other, and with me. They also looked up words in the class dictionary. While they were working, I moved around the class, checking what was happening, and helping students where they needed it. I also encouraged students to use English in their discussions, speaking to them in English myself as much as possible.

After the students had finished sharing their ideas, each student wrote the first draft of their letter. Once again, I moved around the room as they were writing to observe. I noticed that most students’ letters were of a better quality than usual, with the ideas organised in a much more logical way.

Once the students had finished writing their letters, I asked them to exchange their letters with each other and to pretend that they were the person that the letter was addressed to. They then had to write a reply to the letter. The students really enjoyed seeing what the reply to their letter was! It made me realise that when we write something, there is usually a reader in mind. It’s good for students to know that somebody is going to read what they are writing in English, and is going to respond to what they write.

invitation before they started writing one.

It is important that students are familiar with the structures of different texts before they start writing – you can show them examples and models of different texts (see the unit Supporting independent writing in English). It helps students if you use these examples to discuss the features of different texts before they begin writing. Discussion points may include:

- Is it factual or opinionated?

- Is it formal or informal?

- What kind of verb tenses are used?

Activity 2: Thinking of suitable prompts for brainstorming

Follow these steps to try a similar approach in your classroom:

- Select a writing task from your textbook, or one that your students typically do for their examinations. For example: a letter of invitation, or an application; a composition about a topic such as a picnic; an article or a report for a newspaper; a page from a diary, and so on.

- Do a brainstorming session about the topic as a whole class or with students in groups.

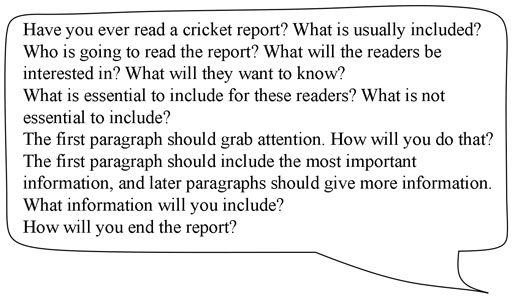

- Ask questions to help students organise the text. For example, imagine your students have to write a report for a newspaper about a local cricket match. You could ask them the following questions:

- Give students some time (such as five minutes) to note down their ideas individually.

- Put students into pairs and ask them to share their ideas and discuss how to organise them. The input of classmates helps students to plan a better text – they may add or delete ideas; or they may decide to organise their ideas differently. Again, give a time limit for this activity (such as ten minutes). This keeps students motivated and focused on what they are doing. Move around the room as everyone works, and help where necessary.

- Tell students to write the text, and give an appropriate time limit. Remind them to follow their plan; to divide the text into paragraphs; to pay attention to spelling and grammar; and to keep in mind who the reader is (a sports fan, in this case!)

Pause for thought Here are some questions for you to think about after trying this activity. If possible, discuss these questions with a colleague.

|

Remember that you can change around the students in your groups to make more effective pairs. Sometimes students get bored of working with each other; sometimes students work better with students of a similar ability. Experiment and see what works best. Planning takes time, and the amount of time will vary depending on the task or topic. It can be a good idea to give a time limit for planning, and to tell students the benefits of planning.

3 Using peer review

‘Reviewing’ means reading through written work and finding ways to improve it. It is possible for students to review their own writing, although it can often be difficult for writers to notice their own mistakes and identify areas where they could improve.

One strategy you can use is conducting a peer review, which means getting students to read through and comment on each other’s written work. This has great value because:

- by reading other students’ work, students become more aware of what is required in the task and develop important skills of self-evaluation

- it can be easier to accept observations and suggestions made by a classmate than by a teacher

- classmates may understand the writer’s feelings more, and may be more open with their comments and suggestions

- it can be very motivating for students to read their classmates’ work, and can make students enjoy writing more.

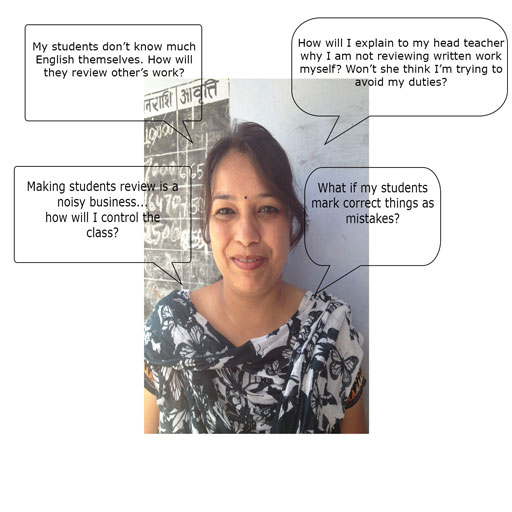

Many teachers are anxious about using peer review. Try Activity 3, which explores some of the issues of using peer review with your students.

Activity 3: Using peer review

This is an activity for you to undertake on your own or with other teachers.

Some teachers, such as Mrs Jadhev in Case Study 2, have many questions about the idea of students reviewing their own work or the work of their classmates. Read Mrs Jadhev’s questions. Are they similar to your own? What answers would you give her? If you can, discuss her questions with a colleague.

Here are some answers given by another teacher. Which of these do you agree with? Read them and see if these would work in your own classroom:

- Correcting classmates’ written work requires students to read the texts carefully. The act of reading is a learning experience for students. Even if they cannot make corrections, they will be able to get a general idea of what is wrong about the passage.

- Involving students in group and pair activities does create a lot of noise, but that happens only the first few times. Once students get into the habit of forming groups for some activity, they settle down quickly.

- Before trying out group review activities, it is a good idea to share the plan with the headteacher. This way, you can get their support and also ask other colleagues to help.

Case Study 3: Mr Rath uses a way to get students to review each other’s written work

Mrs Pallavi Saikia was the headmistress of a secondary school. Last year, when Mrs Saikia recruited a new English teacher, Mr Rath, she found the young man complaining all the time about the amount of corrections he had to do. She decided to demonstrate to Mr Rath and the other English teachers how to get students to review each other’s work. She chose Class VIII, a particularly large and noisy class, and gave them a writing task: ‘What to do when a tsunami warning is announced’ (from the NCERT Class VIII textbook Honeydew). Mr Rath wrote about his experience in his journal.

When the students had composed their texts, Mrs Saikia divided the class into five groups, and gave them names: the Grammarians, the Punctuators, the Content Seekers, the Spell Checkers and the Style Gurus. She also rearranged the classroom so that the members of each group sat facing one another across one desk.

Mrs Saikia announced to the groups that they were her officers, and had to help her review their scripts. The students were very excited. After Mrs Saikia had explained the meanings of the group names, the students understood what they had to do.

She made her instructions clear: the Grammarians had to check each written passage on the Tsunami topic for use of correct grammar, the Punctuators had to check for punctuation mistakes, and so on. Each group had a different job, and when they finished marking their scripts, they had to pass the set to the next group. Mrs Saikia set a rule for the activity that each group had to mark using a different colour, because colour-coding of mistakes would help the writer to realise exactly what category of revision was necessary (grammar, punctuation, etc.).

The students finished this task over three class periods. Mrs Saikia returned the scripts to each writer, and made them sit quietly for ten minutes, reading through the revisions made. She moved around the class, pausing to clarify to students the mistakes made, and helping them to change them accordingly.

I noticed that because of her inventiveness, Mrs Saikia had made a difficult job seem easy. The idea of using interesting group names was what I particularly liked. I realised that Mrs Saikia’s method of getting students to review each other’s work was a very good learning experience for students, and also saved the teacher’s time. I decided to try it out in my own classes.

Activity 4: Try in the classroom – peer review of written work

Next time your students compose a text in English, get them to review their own work, or the work of their classmates. You can do the same as the headteacher in Case Study 3 did, and divide your students into groups that look out for different aspects of writing: grammar, punctuation, spelling, content and style.

An alternative technique is to use a checklist for this (see Resource 3 and the unit Supporting language learning through formative assessment). Write the points on a piece of chart paper and stick it on the wall so that it is always there for the students to see. With this checklist, students can read through each other’s work and make comments about mistakes or things that could be improved.

Once texts have been reviewed, students can exchange their work, and then write a final draft incorporating the comments from their classmates.

Did your students enjoy this activity? What did they learn? How might you improve the activity next time?

4 Summary

This unit has explored a number of different classroom techniques to develop your students’ writing: brainstorming, pair work and peer review. In all these techniques you are using the idea that learning can be a social activity in which you and your students can co-construct knowledge through sharing and building on each other’s thoughts and experiences.

Using the techniques in this unit will help all of your students to become more effective and accurate writers in English and in other languages. It will also help them to develop their creative and critical skills, and to collaborate and share with others.

You can find more ideas for writing activities in Resource 4. If you would like to improve your own writing skills, you can find links and tips in Resource 5. There are also suggestions for further reading in the additional resources.

Other secondary English teacher development units on this topic are:

- Supporting independent writing in English: You can learn more about helping students to develop their writing skills in this unit.

- Supporting language learning through formative assessment: You can learn more about using writing activities for assessment purposes in this unit.

Summary ideas for developing your students’ writing skills

- If you don’t have much time to do the activity, your students could write fewer texts, but spend more time on each one.

- You don’t have to do everything in this unit with every writing task. You might decide to do just brainstorming or review.

- You don’t have to do everything suggested in this unit in one class. You can generate ideas and plan in one class, write a first draft in another class, and then review them in another. Sometimes, it’s a good idea to leave time between writing drafts.

- Encourage students to keep a record of mistakes that they make repeatedly. They can refer to this when they write and review.

- Get students to read each other’s work regularly. It’s motivating, and quality and accuracy often improves.

- Take in some of your students’ written work from time to time. Mark the work and use it for your records about your students’ performance. Make sure you take in work from different students each time, so that you can cover the whole class over a period of time. (See the unit Supporting language learning through formative assessment.)

- Display written work when you can. You can hang it on the blackboard, or on string on a wall. Once again, this is very motivating for students, and also makes them think about their presentation.

Resources

Resource 1: Talk for learning

Why talk for learning is important

Talk is a part of human development that helps us to think, learn and make sense of the world. People use language as a tool for developing reasoning, knowledge and understanding. Therefore, encouraging students to talk as part of their learning experiences will mean that their educational progress is enhanced. Talking about the ideas being learnt means that:

- those ideas are explored

- reasoning is developed and organised

- as such, students learn more.

In a classroom there are different ways to use student talk, ranging from rote repetition to higher-order discussions.

Traditionally, teacher talk was dominant and was more valued than students’ talk or knowledge. However, using talk for learning involves planning lessons so that students can talk more and learn more in a way that makes connections with their prior experience. It is much more than a question and answer session between the teacher and their students, in that the students’ own language, ideas, reasoning and interests are given more time. Most of us want to talk to someone about a difficult issue or in order to find out something, and teachers can build on this instinct with well-planned activities.

Planning talk for learning activities in the classroom

Planning talking activities is not just for literacy and vocabulary lessons; it is also part of planning mathematics and science work and other topics. It can be planned into whole class, pair or groupwork, outdoor activities, role play-based activities, writing, reading, practical investigations, and creative work.

Even young students with limited literacy and numeracy skills can demonstrate higher-order thinking skills if the task is designed to build on their prior experience and is enjoyable. For example, students can make predictions about a story, an animal or a shape from photos, drawings or real objects. Students can list suggestions and possible solutions about problems to a puppet or character in a role play.

Plan the lesson around what you want the students to learn and think about, as well as what type of talk you want students to develop. Some types of talk are exploratory, for example: ‘What could happen next?’, ‘Have we seen this before?’, ‘What could this be?’ or ‘Why do you think that is?’ Other types of talk are more analytical, for example weighing up ideas, evidence or suggestions.

Try to make it interesting, enjoyable and possible for all students to participate in dialogue. Students need to be comfortable and feel safe in expressing views and exploring ideas without fear of ridicule or being made to feel they are getting it wrong.

Building on students’ talk

Talk for learning gives teachers opportunities to:

- listen to what students say

- appreciate and build on students’ ideas

- encourage the students to take it further.

Not all responses have to be written or formally assessed, because developing ideas through talk is a valuable part of learning. You should use their experiences and ideas as much as possible to make their learning feel relevant. The best student talk is exploratory, which means that the students explore and challenge one another’s ideas so that they can become confident about their responses. Groups talking together should be encouraged not to just accept an answer, whoever gives it. You can model challenging thinking in a whole class setting through your use of probing questions like ‘Why?’, ‘How did you decide that?’ or ‘Can you see any problems with that solution?’ You can walk around the classroom listening to groups of students and extending their thinking by asking such questions.

Your students will be encouraged if their talk, ideas and experiences are valued and appreciated. Praise your students for their behaviour when talking, listening carefully, questioning one another, and learning not to interrupt. Be aware of members of the class who are marginalised and think about how you can ensure that they are included. It may take some time to establish ways of working that allow all students to participate fully.

Encourage students to ask questions themselves

Develop a climate in your classroom where good challenging questions are asked and where students’ ideas are respected and praised. Students will not ask questions if they are afraid of how they will be received or if they think their ideas are not valued. Inviting students to ask the questions encourages them to show curiosity, asks them to think in a different way about their learning and helps you to understand their point of view.

You could plan some regular group or pair work, or perhaps a ‘student question time’ so that students can raise queries or ask for clarification. You could:

- entitle a section of your lesson ‘Hands up if you have a question’

- put a student in the hot-seat and encourage the other students to question that student as if they were a character, e.g. Pythagoras or Mirabai

- play a ‘Tell Me More’ game in pairs or small groups

- give students a question grid with who/what/where/when/why questions to practise basic enquiry

- give the students some data (such as the data available from the World Data Bank, e.g. the percentage of children in full-time education or exclusive breastfeeding rates for different countries), and ask them to think of questions you could ask about this data

- design a question wall listing the students’ questions of the week.

You may be pleasantly surprised at the level of interest and thinking that you see when students are freer to ask and answer questions that come from them. As students learn how to communicate more clearly and accurately, they not only increase their oral and written vocabulary, but they also develop new knowledge and skills.

Resource 2: Top-ranked women tennis players

| Name | Ranked on | Weeks as No. 1 |

|---|---|---|

| Maria Sharapova (Russia) | 22 August 2005 | 1 |

| Lindsay Davenport (US) | October 2004 | 82 |

| Amelie Mauresmo (France) | 13 September 2004 | 5 |

| Justine Henin-Hardenne (Belgium) | 20 October 2003 | 45 |

| Kim Clijsters (Belgium) | 11 August 2003 | 12 |

| Serena Williams (US) | 8 July 2002 | 57 |

| Venus Williams (US) | 25 February 2002 | 11 |

| Jennifer Capriati (US) | 15 October 2001 | 17 |

| Lindsay Davenport (US) | 12 October 1998 | 82 |

| Martina Hingis (Switzerland) | 31 March 1997 | 209 |

| Arantxa Sanchez-Vicario (Spain) | 6 February 1995 | 12 |

| Monica Seles (US) | 11 March 1991 | 178 |

| Steffi Graf (Germany) | 17 August 1987 | 377 |

| Tracy Austin (US) | 7 April 1980 | 22 |

| Martina Navratilova (US) | 10 July 1978 | 331 |

| Chris Evert (US) | 3 November 1975 | 362 |

Resource 3: A checklist that students can use to review their own or their classmates’ writing

Here’s a useful checklist for reviewing any written work. You can use checklists like these to correct, mark and assess written work (see Supporting language learning through continuous assessment):

- Does the text meet the task? (Has the student written the assignment that they were asked to? For example, has the student written a newspaper report about a local cricket match, or has the student written about a biography of their favourite cricket player?)

- Is the text clear and easy to understand? Is it organised and sequenced logically?

- Is there a wide range of vocabulary? Are words repeated often?

- Are there any spelling or grammar mistakes, or mistakes with punctuation?

- Is the style appropriate for the reader? (For example, a cricket report for the newspaper should contain facts, and it should be interesting to read.)

- What’s good about the text? What is interesting about it?

Resource 4: More writing activities

- Writing activities that use stages of the writing process: http://www.readwritethink.org/ professional-development/ strategy-guides/ implementing-writing-process-30386.html

- A list of ideas for writing activities: https://www.teachingenglish.org.uk/ article/ writing-activities

Resource 5: Develop your own English

Here are some tips for developing your own writing skills:

- Read as much as you can in English. Good writers are often also good readers! Reading as much as possible will help you to develop your vocabulary and language use.

- Write as much as you can in English: shopping lists, diaries, notes – whatever you can. This will help you develop confidence in writing, and will develop your fluency.

- Remember that you can take time when you write something. You can write as many drafts as you like, and you can revise and edit your work.

- Share your written work with your peers. It’s always a good idea to get feedback.

Additional resources

Links to articles about process writing:

- ‘Approaches to process writing’: http://www.teachingenglish.org.uk/ articles/ approaches-process-writing

- ‘Product process writing: a comparison’: http://www.teachingenglish.org.uk/ articles/ product-process-writing-a-comparison

- ‘Planning a writing lesson’: http://www.teachingenglish.org.uk/ article/ planning-a-writing-lesson

- ‘How to approach discursive writing’: http://www.teachingenglish.org.uk/ article/ how-approach-discursive-writing

- Creativity and brainstorming in ELT: http://eslbrainstorming.webs.com/

- ‘Effective writing’: http://orelt.col.org/ module/ 4-effective-writing

References

Acknowledgements

Except for third party materials and otherwise stated below, this content is made available under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike licence (http://creativecommons.org/ licenses/ by-sa/ 3.0/). The material acknowledged below is Proprietary and used under licence for this project, and not subject to the Creative Commons Licence. This means that this material may only be used unadapted within the TESS-India project and not in any subsequent OER versions. This includes the use of the TESS-India, OU and UKAID logos.

Grateful acknowledgement is made to the following sources for permission to reproduce the material in this unit:

Resource 2: Table R2.1 adapted from the Class XI textbook Beehive (2006), NCERT, http://ncert.nic.in/.

Every effort has been made to contact copyright owners. If any have been inadvertently overlooked the publishers will be pleased to make the necessary arrangements at the first opportunity.

Video (including video stills): thanks are extended to the teacher educators, headteachers, teachers and students across India who worked with The Open University in the productions.