Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Thursday, 5 February 2026, 6:58 AM

TI-AIE: Transforming teaching-learning process: leading assessment in your school

What this unit is about

Assessment has been largely associated with success or failure in examinations. Exam success is important and is associated with access to a good college, social status and success in later professional life. However, the focus on preparation for exams can adversely affect the learning experience. The NCF (NCERT, 2005, p. 71) recognised the depth of the problem when it stated that:

We are concerned about the ill effects that examinations have on efforts to make learning meaningful and joyous for children. Currently, the board examinations negatively influence all testing and assessment throughout the school years, beginning with pre-school.

In this unit you will explore assessment as an opportunity to monitor and guide student development when it is made integral to everyday classroom practice. Such continuous assessment provides regular feedback to teachers about students’ learning that can in turn be used to help the students in your school to become more effective learners. In order to use assessment to promote learning, your teachers will need to assess and monitor their students by collecting evidence, analysing information, modifying learning activities and providing feedback. Assessment used in this way will improve the learning outcomes of all your students.

Learning Diary

During your work on this unit you will be asked to make notes in your Learning Diary, a book or folder where you collect together your thoughts and plans in one place. Perhaps you have already started one.

You may be working through this unit alone, but you will learn much more if you are able to discuss your learning with another school leader. This could be a colleague with whom you already collaborate, or someone with whom you can build new relationship. It could be done in an organised way or on a more informal basis. The notes you make in your Learning Diary will be useful for these kinds of meetings, while also mapping your longer-term learning and development.

What school leaders can learn in this unit

- To distinguish between assessment for learning and learning for assessment.

- To lead a strategy for developing formative assessment with teachers in your school.

- To help teachers use evidence and data collected during formative assessment to give feedback that helps students to improve their learning.

1 Formative and summative assessment

There are two types of assessment that are considered distinct from each other because they are used in different ways and for different purposes. You will be very familiar with summative assessment from your own educational experience, but may not have fully explored the value and opportunity in formative assessment – or maybe you are doing it already but were not fully aware of your skill.

- Formative assessment is also referred to by many as ‘assessment for learning’. The major purpose of this type of assessment is to enable students to be given constructive feedback that will help them to learn better and to make effective progress. Such feedback is usually (but not always) given by teachers.

- Summative assessment is also known as ‘assessment of learning’. The purpose of this type of assessment is to enable the teacher to identify the achievement and performance of students at the end of a period of learning, which may be a term or year.

Figure 1 Discussing gaps in student learning.

Summative assessment is usually used to compare one student against others, whereas formative assessment is used to progress learning.

Formative assessment creates a pathway for the student to move on and progress in their learning. It can identify:

- what the student can do and cannot do

- what the students find difficult

- any gaps and misunderstandings the student might have.

It involves:

- dialogue with the student, discussing clear learning goals

- the student being active in achieving their goal

- monitoring of progress, including self- and peer-review.

Timely and useful feedback is part of the process because it helps the student to improve. It is also important that both students and the teacher show persistence until the student achieves their goal, which will almost certainly involve adjustments by the teacher to their teaching to match the student’s needs.

So, formative assessment has a very different purpose and approach from summative assessment, which is more formal. Formative assessment happens in the context of the classroom and builds on the relationship between teacher and student. The main features of formative assessment (Central Board of Secondary Education, 2009) are that it:

- is diagnostic and remedial

- makes provision for effective feedback

- provides a platform for the active involvement of students in their own learning

- enables teachers to adjust teaching to take account of the results of assessment

- recognises the profound influence that assessment has on the motivation and self-esteem of students, both of which are crucial influences on learning

- recognises the need for students to be able to assess themselves and understand how to improve

- builds on students' prior knowledge and experience in designing what is taught

- incorporates varied learning styles into deciding how and what to teach

- encourages students to understand the criteria that will be used to judge their work

- offers an opportunity to students to improve their work after feedback

- helps students to support their peers, and expect to be supported by them.

Formative assessment allows the teacher to build on from where the student is and allows the student to understand what they have to do in order to be successful. Therefore, formative assessment involves the learner and allows the student ownership of their learning.

Continuous and comprehensive evaluation (CCE) is described (Central Board of Secondary Education, 2009) as follows:

The major emphasis of CCE is on the continuous growth of students ensuring their intellectual, emotional, physical, cultural and social development and therefore will not be merely limited to assessment of learner's scholastic attainments. It uses assessment as a means of motivating learners […] to provide information for arranging feedback and follow up work to improve upon the learning in the classroom and to present a comprehensive picture of a learner’s profile.

Activity 1 asks you to think about the differences between formative and summative assessment in a school setting. It is an activity that you could use to start a discussion with your teachers about formative and summative assessment.

Activity 1: Identifying formative and summative assessment

Below is a list of assessment opportunities that can be used in the classrooms in your school. Use your Learning Diary to make two columns, one for formative assessment and one for summative assessment. Now put the assessments from the following list in either column. You may find some could go in either column, depending on the context – for example, singing a song could be summative if it was part of a music exam or formative if it was in preparation for a school performance.

This is an activity that you could do alone, or you may want to broaden it to include others as part of a group activity.

- Pen and paper test

- Recollection from memory

- Hypothesising and performing an experiment in science

- Open book test

- Teacher observation of student

- Cooking to a recipe

- Essays

- Oral responses to questions

- Demonstration

- Performing a song that the student has composed

- Setting a personal best in an athletics race

- Scripting and enacting a play

Discussion

Some of the tasks can be easily identified as providing formative opportunities, such as Option 8, where oral responses allow immediate feedback and discussion. Others would provide summative information, such as the pen and paper test in Option 1, which would lead to a final grade.

However, without further information about the purpose and nature of the assessment, the vast majority are difficult to categorise. For example, a pen and paper test could be used formatively if the results were the start of a discussion with the student about misunderstandings that they may have. Likewise, oral responses to closed questions may result in a ‘score’ that is solely for the teacher’s benefit, in which case they are being used summatively.

Using assessment formatively

You will find it helpful to read Resource 1, ‘Assessing progress and performance’. You might find it useful to share this with your teachers when you open up discussions about the role and style of assessment in your school, looking at what methods might be used and how assessment can be an integral activity in the classroom.

So the three key distinctions between formative and summative assessment are:

- the purpose of the assessment

- how the data is used

- who has ownership of the process.

For students to be partners in formative assessment, they need to become active and reflective learners, using the feedback to take the next steps in their learning. Case Study 1 gives an example of this.

Figure 2 Using formative and summative assessment in the classroom.

Case Study 1: Ravi receives formative assessment

Student Ravi works with another student to write a chapter summary of a book. He thinks afterwards about how long it took them and how disorganised they both were. Ravi was confused about the task and recognised that he did not understand some key words in the chapter. The chapter summary was handed in late and the teacher said it was too short, lacked structure and missed out some key information. The teacher was encouraging about their attempts, however, and they agreed that Ravi would use more structure in his next summary. Ravi was still embarrassed, as he knew he could do better, but this was the first time he had done a chapter summary.

Ravi started to write a vocabulary list for this book as he was obviously missing some of the story and would see if that helped. He also asked his older sister to show him chapter summaries that she had done so he could see some good examples. The next time Ravi decided to try to work with a different partner who was clearer about the task and he would suggest that they divided up responsibilities rather than trying to write it all together. He was not sure whether he was the one who was confused or his partner, and wanted to check that.

Ravi not only reflected on his own learning, but started to look at how to do better next time and what he could do to improve his learning. He looked at how he was working, not just the output. His teacher gave him some useful feedback (formative assessment) and he used this to plan for next time.

As a school leader, you can encourage a joint approach to formative assessment by working not only with teachers but with your students to help them see the benefits of assessing learning as part of their process.

To encourage students to become engaged and active learners, the teacher needs to ensure that they are aware of their own learning process and that they:

- reflect on an activity

- start to analyse what happened

- take action to improve their learning and test their assumptions and conclusions.

Further guidance for your teachers can be found in the Secondary English unit Supporting language through formative assessment.

2 Using formative and summative assessment in the classroom

Case Study 2 tells how one school leader, Mrs Silva, introduced formative assessment to her school using her own experiences as a teacher. She structures her approach to introduce formative assessment in her schools in five steps:

- Familiarising teachers with formative assessment.

- Practical exposure of teachers to formative assessment: observing a class taken by the school leader, Mrs Silva.

- Discussion with teachers on the observed classroom teaching of the school leader, Mrs Silva.

- Observing teachers using formative assessment in their classes.

- Review and reflection.

Case Study 2: Mrs Silva uses formative assessment in the classroom

Mrs Silva had always kept track of each student in her class by making notes about their progress in different lessons. She took pride in making her lessons relevant and useful to the range of students in her class, and she was aware that she could only do this if she knew where each student was in their learning. She had learned over time that she should not assume that the loudest students were the brightest, so she loved to encourage the students who were quietly competent, and see them flourish.

She also believed in recording in some format what students were doing in their activities and providing feedback to each student on their learning and progress. Based on the recording and analysis, she planned how to deal with her students so that their learning would improve.

With a recent promotion to be the school leader, Mrs Silva was keen to get her three colleagues to build on their students’ prior learning and adjust their teaching to take account of what they found. This is what she said about her approach.

Step 1: Familiarising teachers with formative assessment

I was met with blank faces when I started to talk about checking learning in the classroom, and how this could be used help teach in our large and diverse classes.

The teachers were often very ready to talk about how difficult it was to teach students who were at different stages in one lesson, but they did not recognise how they could teach more effectively if they knew the levels of students’ current learning more accurately. So I started talking about formative assessment and how this could improve the students’ learning.

Step 2: Practical exposure of teachers to formative assessment: observing a class taken by the school leader

I realised that talking about it was not going to convince them, so I decided to invite them into my lessons to show them what I meant. I opened up a maths lesson and a language lesson to observers. I asked them to make notes about the different ways in which assessment was taking place in the lesson and how many times this was happening. I suggested that this could be me assessing the students, or the students assessing themselves or each other. I asked the teachers to make a note of how assessments were recorded (or not), and how I used the assessment to inform my teaching; for example, what questions I asked, what comments I made and what examples I used.

I also highlighted that it was important that they wrote down what comments I made to help students when they were stuck, and how I gave feedback to students from time to time. This was to make them realise how necessary and important it is to provide immediate feedback to students in a way that the students could improve what they were doing.

Step 3: Discussion with teachers on the observed classroom teaching of the school leader

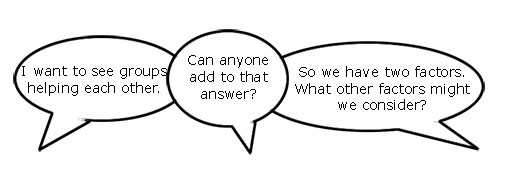

We had a meeting where we discussed my approach to assessing students as part of ongoing teaching and learning. Some of the things that had surprised the teachers were that I had asked one student to assess her partner during paired work and that during groupwork I had asked the groups to assess each other and give feedback – taking over my role as a teacher.

The discussion broadened out to a list of questions they might ask to assess learning of students in their own classrooms. I was keen that these questions were used in a supportive manner and not that students would feel tense or interrogated. If a student could not answer, they should be passed over for another to try while noting that something has not been understood.

Step 4: Observing teachers using formative assessment in their classes

I asked for invitations for me to come to observe a lesson myself in a month’s time. They needed time to practice their ideas. I informed them that I would be noting down my observations as it would not be possible for me to remember everything that was happening in so many classes. During my observations I was delighted to see the teachers using questions that made their students think and allowed the teachers to know what the students understood. I also saw that they were giving helpful feedback when students were stuck. The students were visibly engaged and ready to respond in most classes.

Step 5: Review and reflection

After the observations we went back to our initial lists and refined them, adding more questions. During this interaction with all the teachers in my school, we:

- discussed the problems they faced

- shared experiences of what and how they undertook assessment in their classes, and broadly decided what was required to be done to help students

- modified their individual teaching/learning plans

- shared the new plans with each other.

One teacher, Mrs Mehta, shared an idea during the discussions that was then used by many teachers in their classrooms. She told us that she had used a fun way with her maths class to quickly assess her students. The students raised an open hand if they were struggling with a concept, and a closed fist if they were confident that they understood it. She could use this assessment at any point in the lesson to slow down her delivery or go on to the next stage. The students had asked for an additional sign of an opening and closing hand to indicate when they were nearly there! Several of us now use this technique and the students sometimes even raise a flashing or open hand without being asked.

Mrs Mehta’s idea was a quick and useful way to allow her students to let her know if they understood their work. However, there are a couple of points that you, as a leader, would need to look for in order to make sure that this idea was being used formatively:

- Do the students know what they are working towards? Do they have the criteria to judge for themselves how successful they are? In the case of Mrs Mehta, she may have listed skills that her students needed to learn on the blackboard, or given them a complex question that needed a good understanding of the mathematics they were learning in order to solve. The students could then judge whether they could use the skills or solve the problem.

- What happened as a result of the assessment? Assessment is only formative when the subsequent learning activity is modified to take into account what the assessment showed. Mrs Mehta slowed down when she saw that the students were not keeping up, but sometimes teachers must have several ideas to hand to allow each student to continue to progress.

3 Assessment practice in your school

Students need to be supported to develop these assessments for learning skills. To do this, school leaders and teachers must:

- understand the principles of assessment for learning

- know how these skills might be developed through classroom activities, and how these activities might provide opportunities for feedback to students and help to plan teaching and learning in a more effective manner.

Before implementing change in assessment in a school, it is always necessary to understand what is currently happening and how teachers view assessment. The next activity aims to help you find out what kind of assessment is happening in your school’s lessons so that you can enable teachers to adopt creative strategies for assessing in class.

Activity 2: Looking at assessment practice in your school

Ask a maximum of five teachers to describe one assessment task that they have used that week. Ask them what they learnt from the assessment about the students and what the students learnt from it.

In finding out the extent to which formative assessment is being used, you may want to probe them for examples of where they have given immediate assessment feedback to students or changed the learning task in order to help students improve their learning. This will help you determine whether your teachers are using formative assessment without being conscious of it.

Once you have had these conversations, answer the following questions, keeping a note of the answers in your Learning Diary:

- What types of assessment seems to be most common?

- Is there evidence of formative assessment happening? If so, give examples.

- Do the teachers express a clear desire for students to learn from assessment feedback? In other words, do they understand the role of assessment for learning as opposed to assessment of learning?

- How could you suggest changing the purpose or use of the assessments they discussed with you to become formative?

Discussion

Depending on the background of the teachers in your school and the way the curriculum has been interpreted by the staff, there may be a greater emphasis on one sort of assessment than the other. You also need to be aware that their answers will reflect to some extent what they think you expect from them.

You may discover that there is some excellent practice already in place in certain parts of the curriculum that you can use as an example of good practice. You might like to follow up this activity with a staff meeting where you emphasise the learning possibilities from assessment and highlight the appropriate use of formative assessment that you have discovered. You may also decide to focus on assessment in your walks around the school to help you identify areas of good practice and support staff who need additional help.

You may want to work closely with small groups of teachers to help them establish regular formative assessment opportunities.

Involve the students

The perspective of the staff and their perspectives on assessment are very important. However, they are only one part of the process. Fundamental to the successful implementation of formative assessment in a school are two questions:

- Are teachers getting the information they need from the assessment opportunities in order to help students learn effectively?

- Are students getting the feedback they need in order to learn effectively and develop their abilities?

It is vital that time is put aside to ask students about their experiences of formative assessment and whether they can suggest how the assessments and the feedback can be improved. Involving students should ideally be embedded in each assessment opportunity, so that teachers can understand what the students have gained from the assessment and jointly identify the next steps needed in their learning. In this way, assessment becomes about the individual, also known as differentiated assessment. You may find Resource 2, ‘Monitoring and giving feedback’, useful to share with your team.

4 Establishing learning goals

Formative assessment is only effective when teachers know what students are moving towards. As a leader, it is your responsibility to make sure that teachers have goals for the end of an academic year, the end of a sequence of lessons and for completing a particular activity.

Clear goals for students over the short, medium and long term is essential in helping teachers develop their use of formative assessment. Activity 3 will help you to think about how you might support teachers to do this, using a rubric as a tool. Resource 3 offers some guidance on writing a rubric to assess different levels of attainment. Tables 1 and 2 are examples of two contrasting rubrics that assess at different levels and against different criteria.

| Performance levels | Idea: generating an interpretation | Evidence: using support from the text | Response: learning with and from other students |

|---|---|---|---|

7 Extends interpretation | Extends idea to interpret text as a whole

| Brings together evidence from the whole text

| Seeks out other students’ ideas

|

6 Builds interpretation | Elaborates on own ideas

| Builds case from several different passages

| Incorporates other students’ ideas and evidence

|

5 Explains answer | Explains how an idea answers the question

| Explains how a passage supports an idea

| Explains and gives reasons for agreement and disagreement

|

4 Understands issues | Fully understands the interpretative issue

| Understands the need for evidence

| Understands and roughly summarises other students’ ideas

|

3 Recognises alternatives | Asserts a considered answer, aware of alternative ideas

| Supports answer against alternative answer

| Recognises alternative answers and agrees or disagrees simply |

2 Offers simple, quick answers | Gives quick, simple answer to question

| Tends not to volunteer support; offers support only when asked

| Reacts briefly/quickly to other students’ answers without talking about them |

1 Begins to answer | Talks about the text without addressing the question | May retell the story or event, or give an opinion about something mentioned in the text | Allows others to speak without interrupting |

| Category | Expert | Competent | Novice | Needs development |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Craftsmanship | Form is carefully planned, form is balanced. Edges are smooth, refined. Walls are even thickness. Joining is secure and hidden. All surfaces are smooth, without burrs or wobbles. | Form is somewhat planned, and is slightly asymmetrical. Most edges are smooth, refined. Walls are even thickness with minimum wobbles. Joining is secure and hidden. Most surfaces are smooth, without any burrs. | Form is unplanned and lacks balance. Some edges are smooth but many are unrefined. Joining is secure but is obvious. Walls vary in thickness with some ‘wobbles’. Surfaces are mostly smooth with some wobbles, but some burrs are evident. | Form lacks planning and effort. Surfaces are uneven thickness, burrs readily appear. Joining is insecure. Surfaces and edges are unrefined. |

| Creativity | Design is unique, and displays elements that are totally their own. Evidence of detail, pattern or unique applications. | Design is expressive; has some unique features. Has ‘branched out’ to some degree. | Design lacks individuality. Has few details or is not appropriate for the form being expressed. Evidence of copying ideas. | Lacks many design elements or interest. Has minimal additional features or copies the ideas of others. Not much attempt to shown individuality. |

| Production/effort | Uses class time to the maximum. Always on task. Time and effort are evident in the execution of the piece. | Uses class time for work but is sometimes distracted by others. Work falls short of excellence. | Has difficulty focusing on the project much of the time. Easily distracted by others. | Hardly evidences caring about quality of the work. No additional effort is noted than to complete it. |

| Work habits/attitude | Is respectful and open to positive suggestions. Cleans work area thoroughly. | Is respectful and accepts suggestions. Cleans work area most of the time. | Lacks openness for suggestions for improvement. Has difficulty being on task to cleaning up. | Leaves cleaning up to others. Has an ‘attitude’ and is not open to assistance from suggestions. |

Activity 3: Supporting teachers in establishing learning goals

In the following dialogue, the school leader is working with a teacher to help them create a rubric for assessing the skill of writing in a play format. As you read it, note in your Learning Diary how the school leader avoids telling the teacher what to do, enabling her to think for herself.

| Teacher | I have asked the students to convert the story into a play, beginning with the setting and the cast and characters. I am making a chart on stage directions that they can use and putting it up on the blackboard. I am not sure about how I will organise a rubric for the task I have given them. |

| School leader | Well, a good place to start would be identifying what you want the students to be able to demonstrate by writing the play. For example, do you want them to use all of the stage directions on your chart? |

| Teacher | Do you think they would be able to do that? |

| School leader | Well, that depends on how many you are putting on the chart and how frequently they are used generally in play-writing. |

| Teacher | Most of them are used very frequently. I have eight stage directions on the display board. The easy two are ‘exits’ and ‘enters’, and the difficult ones are ‘from offstage’, ‘moving downstage’, ‘speaking from centre stage’ … |

| School leader | So the student who uses all the stage directions in his play script should know why they are to be used and that they have a reason for being used? |

| Teacher | Yes, I have discussed all that in class when they are presenting their skits, so that they also learn about the craft of theatre when putting up a show. I think it will help when we do the annual day. |

| School leader | I now understand why the students of your class always present themselves well in assembly. Now I wonder whether a student who uses all eight stage directions appropriately would be graded as outstanding? |

| Teacher | Hmmm. I think they would be outstanding if they use more stage directions than those on display. I see what you mean. So I could say that if only two stage directions are used, the student needs attention. An A-grade student would be the one who used all eight on display. I guess the use of six directions would be average, and a satisfactory C could be given to students whose scripts had four stage directions incorporated. |

| School leader | Let us not forget appropriateness. So I would say that the ‘Outstanding’ grade, also implies that the directions are used appropriately. |

| Teacher | OK, let me work on it and get back to you. I have some more criteria in mind. |

Discussion

You would have noted that the school leader’s questions are helping the teacher to think about her assessment. She leaves with greater clarity and a desire to create the assessment rubric with more criteria.

Critical to this teacher’s developing understanding is that the criteria she would have used (the number of stage directions used) is not formative assessment. If she had just used her initial criteria (number of stage directions = grade), then it is unlikely that she would have been able to provide effective formative feedback to improve the students’ learning, other than to use more of the stage directions.

By adding criteria to other aspects of the task (e.g. the appropriate use of the stage directions), the teacher or students themselves can assess for learning, rather than prompt students to assess of learning.

Helping to move teachers towards using criteria to support assessment for learning requires time: not only for understanding the concept, planning assessment opportunities and developing rubrics (where assessment criteria are linked to performance standards), but also to develop a different sort of dialogue in the classroom. This dialogue may be between teacher and student using the rubric to discuss their learning and next steps for learning, but equally could involve students in self- or peer-assessing to help them understand and take control of their own learning.

If you have not used a rubric before, look at the guidance in Resource 3 to understand how to write and use a rubric that assesses how far students have met criteria around knowledge and skills. You might develop a template for your teachers to use in order to encourage their adoption of this approach.

Activity 4: An example of using a rubric

Below is an example of a dialogue between teacher and student using a marked assignment and an assessment rubric. As you read it, make notes in your learning diary of what the teacher does to support the student’s learning. Imagine that this is a dialogue that you observe in your school and think about the feedback you would give to the teacher.

| Teacher | Here’s your answer sheet – your grade has improved since the last assessment. Have a look at it and tell me if you can see what you have done well and where you need to improve further. |

| Student | I wanted an A. You have awarded me a B+. It doesn’t look right to me! I have answered everything. I can’t tell what I’ve missed out on. |

| Teacher | Let’s take a look at the rubric together. The second criterion regards the sequence of the reasons for Rani Laxmibai’s decision. |

| Student | Well, this is the right sequence according to me! |

| Teacher | I understand that you feel your sequence is good enough for you. In history we often need to get out of our skin and think from the point of view of the people who make the decisions. Let’s see now – why do you think you should begin with the immediate cause and then discuss causes that built up the conflict? |

| Student | In fact, I guess the immediate cause is usually unimportant. You know they were angry because of the unfair decisions made over years and they just used the rumours about the cartridges as an excuse. |

| Teacher | You are really quite upset but you are thinking straight! Your guess is absolutely right! So when you start with the immediate cause, you are in a way highlighting the excuse. Then you systematically identify the causes that were building up over time. If you look at the eight reasons in this case, you can identify a hierarchy that makes one of them the most important cause. |

| Student | I see what you mean. So I have to be more careful about the way I sequence the reasons and I have to have a rationale for the sequencing as well! |

| Teacher | Absolutely. Do that, and there’s no way I can deny you an A in next week’s assessment. You’ve written it really well. |

| Student | Thank you so much! If I write these answers in a more thoughtful sequence, would you please have a look at them? |

| Teacher | Sure! Do them at home, and show them to me tomorrow. |

| Student | Thanks again, this was really helpful! |

Discussion

This dialogue starts after a grade has been awarded. The student starts off defensively and angry. Grades tend to have this effect: if the grade had been awarded after a discussion about improvement had been held, the student would have been much more receptive. As can be seen, the student is keen to improve. By the end of the session she knows what needs to be done and has come to that understanding herself by using the rubric more. The conversation has used the clearly set out criteria in the rubric to highlight what the student achieved and what they need to do to progress. There was no need for any discussion of grades. Instead, a dialogue about what was achieved and what more could be achieved would enable every student to make progress without making them feel unsuccessful.

Supporting other teachers to develop their ability to discuss learning in this way requires careful planning. You might consider opportunities to model effective practice, such as asking teachers to develop and share their own case studies, or observing lessons and praising effective formative feedback.

You might also want to consider how you can support students to engage with formative assessment – you may have noted that this student initially only looked at the grade and did not want to engage with the discussion about how to improve. As formative assessment becomes the norm in the classroom, students will engage and become more self-sufficient learners.

5 Using assessment data to track students’ progress

As well as supporting students to develop more holistically as learners, assessment for learning allows teachers to regularly collect assessment data about students’ progress. This in turn allows for more individualised and targeted activities and feedback that is appropriate to the student, also known as differentiation.

Some students make incremental shifts in their learning; others improve by leaps and bounds. Teachers who are aware of how students learn will have a variety of activities that can be run simultaneously to meet the different needs of the class. The aim is to challenge each student appropriately, so that no student is left behind, and those making good progress feel that they are also learning effectively.

Every student in class has a different starting point. The teacher must know each student’s baseline. This enables teachers to plan their activities so that they are appropriate for all their students’ needs, and can differentiate the formative feedback on these activities to support all students to learn effectively.

Activity 5: Using assessment data to track students’ progress

Spend some time thinking about how you will check that your teachers:

- have a baseline for the students in the classes they teach

- offer differential learning

- recording formative assessments

- track their students.

Make notes in your Learning Diary about the sources of information that you can use and how you will get evidence – assumptions and reputations can get in the way. You may find that you currently have very little hard evidence of these practices and your notes will then be about what you will do to build up to the point of having such data.

Discussion

Depending on the context of your school, you may feel that your teachers are already establishing assessment for learning as a daily part of their practice. Alternatively, you may feel that they are at the very start of understanding its potential. Whatever the position you are in, embedding assessment for learning takes time and effort. This is because it underpins so many aspects of teaching, such as classroom activities, the nature and purposes of assessments, and the nature of teacher–student dialogue.

Leading such change is likely to require careful planning and monitoring, both of which will depend on your context and how many teachers you are working with. In a small school, you may be able to discuss the ideas with all your teachers and monitor the change through observing, sharing ideas and discussing the outcomes. In a larger context, you may choose to start with a small group of teachers and develop a working example that others in the school can learn from.

The data that is gathered provides the evidence on which to build sound teaching strategy and short- and longer-term planning for classes and individual students. Rather than guessing levels of learning, comprehension, skills and attitudes, formative assessment provides hard evidence of actual levels and the baselines for measuring individual and class progress.

6 Summary

This unit has considered the role of assessment for learning in creating a more supportive assessment strategy within a school. It has identified that formative assessment has the potential to provide immediate and differentiated feedback to students that can help them to progress in learning content and developing skills that will ultimately make them more effective learners.

This unit has also suggested some strategies for leading teachers to use assessment for learning strategies in their classes. This includes identifying current practice and understanding how to develop and use assessment rubrics.

This unit is part of the set or family of units that relate to the key area of transforming teaching-learning process (aligned to the National College of School Leadership). You may find it useful to look next at other units in this set to build your knowledge and skills:

- Leading improvements in teaching and learning in the elementary school

- Leading improvements in teaching and learning in the secondary school

- Supporting teachers to raise performance

- Leading teachers’ professional development

- Mentoring and coaching

- Developing an effective learning culture in your school

- Promoting inclusion in your school

- Managing resources for effective student learning

- Leading the use of technology in your school.

Resources

Resource 1: Assessing progress and performance

Assessing students’ learning has two purposes:

- Summative assessment looks back and makes a judgement on what has already been learnt. It is often conducted in the form of tests that are graded, telling students their attainment on the questions in that test. This also helps in reporting outcomes.

- Formative assessment (or assessment for learning) is quite different, being more informal and diagnostic in nature. Teachers use it as part of the learning process, for example questioning to check whether students have understood something. The outcomes of this assessment are then used to change the next learning experience. Monitoring and feedback are part of formative assessment.

Formative assessment enhances learning because in order to learn, most students must:

- understand what they are expected to learn

- know where they are now with that learning

- understand how they can make progress (that is, what to study and how to study)

- know when they have reached the goals and expected outcomes.

As a teacher, you will get the best out of your students if you attend to the four points above in every lesson. Thus assessment can be undertaken before, during and after instruction:

- Before: Assessing before the teaching begins can help you identify what the students know and can do prior to instruction. It determines the baseline and gives you a starting point for planning your teaching. Enhancing your understanding of what your students know reduces the chance of re-teaching the students something they have already mastered or omitting something they possibly should (but do not yet) know or understand.

- During: Assessing during classroom teaching involves checking if students are learning and improving. This will help you make adjustments in your teaching methodology, resources and activities. It will help you understand how the student is progressing towards the desired objective and how successful your teaching is.

- After: Assessment that occurs after teaching confirms what students have learnt and shows you who has learnt and who still needs support. This will allow you to assess the effectiveness of your teaching goal.

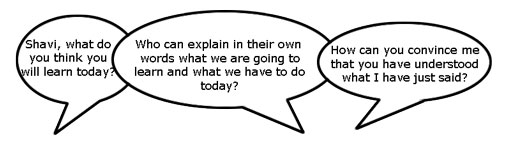

Before: being clear about what your students will learn

When you decide what the students must learn in a lesson or series of lessons, you need to share this with them. Carefully distinguish what the students are expected to learn from what you are asking them to do. Ask an open question that gives you the chance to assess whether they have really understood. For example:

Give the students a few seconds to think before they answer, or perhaps ask the students to first discuss their answers in pairs or small groups. When they tell you their answer, you will know whether they understand what it is they have to learn.

Before: knowing where students are in their learning

In order to help your students improve, both you and they need to know the current state of their knowledge and understanding. Once you have shared the intended learning outcomes or goals, you could do the following:

- Ask the students to work in pairs to make a mind map or list of what they already know about that topic, giving them enough time to complete it but not too long for those with few ideas. You should then review the mind maps or lists.

- Write the important vocabulary on the board and ask for volunteers to say what they know about each word. Then ask the rest of the class to put their thumbs up if they understand the word, thumbs down if they know very little or nothing, and thumbs horizontal if they know something.

Knowing where to start will mean that you can plan lessons that are relevant and constructive for your students. It is also important that your students are able to assess how well they are learning so that both you and they know what they need to learn next. Providing opportunities for your students to take charge of their own learning will help to make them life-long learners.

During: ensuring students’ progress in learning

When you talk to students about their current progress, make sure that they find your feedback both useful and constructive. Do this by:

- helping students know their strengths and how they might further improve

- being clear about what needs further development

- being positive about how they might develop their learning, checking that they understand and feel able to use the advice.

You will also need to provide opportunities for students to improve their learning. This means that you may have to modify your lesson plans to close the gap between where your students are now in their learning and where you wish them to be. In order to do this you might have to:

- go back over some work that you thought they knew already

- group students according to needs, giving them differentiated tasks

- encourage students to decide for themselves which of several resources they need to study so that they can ‘fill their own gap’

- use ‘low entry, high ceiling’ tasks so that all students can make progress – these are designed so that all students can start the task but the more able ones are not restricted and can progress to extend their learning.

By slowing the pace of lessons down, very often you can actually speed up learning because you give students the time and confidence to think and understand what they need to do to improve. By letting students talk about their work among themselves, and reflect on where the gaps are and how they might close them, you are providing them with ways to assess themselves.

After: collecting and interpreting evidence, and planning ahead

While teaching–learning is taking place and after setting a classwork or homework task, it is important to:

- find out how well your students are doing

- use this to inform your planning for the next lesson

- feed it back to students.

The four key states of assessment are discussed below.

Collecting information or evidence

Every student learns differently, at their own pace and style, both inside and outside the school. Therefore, you need to do two things while assessing students:

- Collect information from a variety of sources – from your own experience, the student, other students, other teachers, parents and community members.

- Assess students individually, in pairs and in groups, and promote self-assessment. Using different methods is important, as no single method can provide all the information you need. Different ways of collecting information about the students’ learning and progress include observing, listening, discussing topics and themes, and reviewing written class and homework.

Recording

In all schools across India the most common form of recording is through the use of report card, but this may not allow you to record all aspects of a student’s learning or behaviours. There are some simple ways of doing this that you may like to consider, such as:

- noting down what you observe while teaching–learning is going on in a diary/notebook/register

- keeping samples of students’ work (written, art, craft, projects, poems, etc.) in a portfolio

- preparing every student’s profile

- noting down any unusual incidents, changes, problems, strengths and learning evidences of students.

Interpreting the evidence

Once information and evidence have been collected and recorded, it is important to interpret it in order to form an understanding of how each student is learning and progressing. This requires careful reflection and analysis. You then need to act on your findings to improve learning, maybe through feedback to students or finding new resources, rearranging the groups, or repeating a learning point.

Planning for improvement

Assessment can help you to provide meaningful learning opportunities to every student by establishing specific and differentiated learning activities, giving attention to the students who need more help and challenging the students who are more advanced.

Resource 2: Monitoring and giving feedback

Improving students’ performance involves constantly monitoring and responding to them, so that they know what is expected of them and they get feedback after completing tasks. They can improve their performance through your constructive feedback.

Monitoring

Effective teachers monitor their students most of the time. Generally, most teachers monitor their students’ work by listening and observing what they do in class. Monitoring students’ progress is critical because it helps them to:

- achieve higher grades

- be more aware of their performance and more responsible for their learning

- improve their learning

- predict achievement on state and local standardised tests.

It will also help you as a teacher to decide:

- when to ask a question or give a prompt

- when to praise

- whether to challenge

- how to include different groups of students in a task

- what to do about mistakes.

Students improve most when they are given clear and prompt feedback on their progress. Using monitoring will enable you to give regular feedback, letting your students know how they are doing and what else they need to do to advance their learning.

One of the challenges you will face is helping students to set their own learning targets, also known as self-monitoring. Students, especially struggling ones, are not used to having ownership of their own learning. But you can help any student to set their own targets or goals for a project, plan out their work and set deadlines, and self- monitor their progress. Practising the process and mastering the skill of self-monitoring will serve them well in school and throughout their lives.

Listening to and observing students

Most of the time, listening to and observing students is done naturally by teachers; it is a simple monitoring tool. For example, you may:

- listen to your students reading aloud

- listen to discussions in pair or groupwork

- observe students using resources outdoors or in the classroom

- observe the body language of groups as they work.

Make sure that the observations you collect are true evidence of student learning or progress. Only document what you can see, hear, justify or count.

As students work, move around the classroom in order to make brief observation notes. You can use a class list to record which students need more help, and also to note any emerging misunderstandings. You can use these observations and notes to give feedback to the whole class or prompt and encourage groups or individuals.

Giving feedback

Feedback is information that you give to a student about how they have performed in relation to a stated goal or expected outcome. Effective feedback provides the student with:

- information about what happened

- an evaluation of how well the action or task was performed

- guidance as to how their performance can be improved.

When you give feedback to each student, it should help them to know:

- what they can actually do

- what they cannot do yet

- how their work compares with that of others

- how they can improve.

It is important to remember that effective feedback helps students. You do not want to inhibit learning because your feedback is unclear or unfair. Effective feedback is:

- focused on the task being undertaken and the learning that the student needs to do

- clear and honest, telling the student what is good about their learning as well as what requires improvement

- actionable, telling the student to do something that they are able to do

- given in appropriate language that the student can understand

- given at the right time – if it’s given too soon, the student will think ‘I was just going to do that!’; too late, and the student’s focus will have moved elsewhere and they will not want to go back and do what is asked.

Whether feedback is spoken or written in the students’ workbooks, it becomes more effective if it follows the guidelines given below.

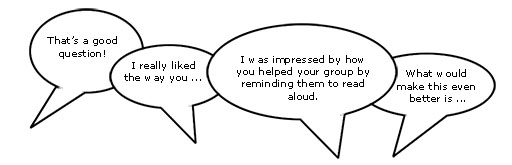

Using praise and positive language

When we are praised and encouraged, we generally feel a great deal better than when we are criticised or corrected. Reinforcement and positive language is motivating for the whole class and for individuals of all ages. Remember that praise must be specific and targeted on the work done rather than about the student themselves, otherwise it will not help the student progress. ‘Well done’ is non-specific, so it is better to say one of the following:

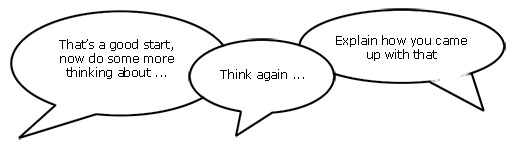

Using prompting as well as correction

The dialogue that you have with your students helps their learning. If you tell them that an answer is incorrect and finish the dialogue there, you miss the opportunity to help them to keep thinking and trying for themselves. If you give students a hint or ask them a further question, you prompt them to think more deeply and encourage them to find answers and take responsibility for their own learning. For example, you can encourage a better answer or prompt a different angle on a problem by saying such things as:

It may be appropriate to encourage other students to help each other. You can do this by opening your questions to the rest of the class with such comments as:

Correcting students with a ‘yes’ or ‘no’ might be appropriate to tasks such as spelling or number practice, but even here you can prompt students to look for emerging patterns in their answers, make connections with similar answers or open a discussion about why a certain answer is incorrect.

Self-correction and peer correction is effective and you can encourage this by asking students to check their own and each other’s work while doing tasks or assignments in pairs. It is best to focus on one aspect to correct at a time so that there is not too much confusing information.

Resource 3: How to design assessment rubrics

Rubrics describe different levels of performance and make these explicit to the student and the teacher. Firstly you need to identify the knowledge; skills and understanding that the student needs to demonstrate and from this you can write success criteria.

Next you need to differentiate different levels of achievement so that you can write your descriptions of levels of performance (maybe three levels). For example you may write the levels like this:

- accurately explains photosynthesis

- explains with some accuracy the process of photosynthesis

- explains photosynthesis with limited accuracy

or:

- shows a comprehensive knowledge of story, themes and characters

- shows a sound knowledge of the story and the roles of some of the characters

- shows a basic knowledge of what the story is about and can name a few characters

or:

- correctly and independently uses the equipment

- uses the equipment with occasional peer or teacher assistance

- attempts to use the equipment with teacher guidance

These level descriptors can be used with students and by students to explain how they have performed and what they need to do to achieve higher.

References

Acknowledgements

Except for third party materials and otherwise stated below, this content is made available under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike licence (http://creativecommons.org/ licenses/ by-sa/ 3.0/). The material acknowledged below is Proprietary and used under licence for this project, and not subject to the Creative Commons Licence. This means that this material may only be used unadapted within the TESS-India project and not in any subsequent OER versions. This includes the use of the TESS-India, OU and UKAID logos.

Grateful acknowledgement is made to the following sources for permission to reproduce the material in this unit:

Table 1: extract from Intellectual Takeout (undated) ‘Middle and high schools critical thinking rubric’, in http://www.intellectualtakeout.org.

Table 2: adapted from: Valerie Burger [Pinterest user] (undated) ‘Art rubrics elementary grade level’, available from http://www.pinterest.com.

Every effort has been made to contact copyright owners. If any have been inadvertently overlooked the publishers will be pleased to make the necessary arrangements at the first opportunity.

Video (including video stills): thanks are extended to the teacher educators, headteachers, teachers and students across India who worked with The Open University in the productions.