Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Wednesday, 4 February 2026, 6:12 PM

TI-AIE: Transforming teaching-learning process: supporting teachers to raise performance

What this unit is about

In an ideal world, all students would achieve good learning gains each year in school, helped by teachers who knew about the latest learning theories and how to apply these to each individual student’s needs. The teachers would be able to do this with the resources provided by the school and despite whatever else was happening elsewhere in their lives.

However, we do not live in an ideal world. Teachers are human beings who sometimes find themselves working not at their best. If they are aware of this, they may only need a small amount of support to improve – but the problem is when the teacher does not realise they can do better and student learning is suffering. This is a sensitive issue that needs careful handling, but is part of the role and responsibility of a good school leader.

In this unit you will learn how to gather evidence about teacher performance and explore some ideas to improve it by using planning supportive development activities. Your teachers are the biggest determinant of student achievement and therefore your influence in promoting teacher performance will directly impact on student learning and outcomes. As a school leader you can enable teachers to have more impact by supporting them to raise their performance.

Learning Diary

During your work on this unit you will be asked to make notes in your Learning Diary, a book or folder where you collect together your thoughts and plans in one place. Perhaps you have already started one.

You may be working through this unit alone, but you will learn much more if you are able to discuss your learning with another school leader. This could be a colleague with whom you already collaborate, or someone with whom you can build new relationship. It could be done in an organised way or on a more informal basis. The notes you make in your Learning Diary will be useful for these kinds of meetings, while also mapping your longer-term learning and development.

What school leaders can learn in this unit

- To assess teacher performance.

- To plan to improve the performance of individual teachers.

- Some ideas on how to conduct constructive meetings with teachers about performance.

- Some ideas to use to maintain the performance of teachers.

1 Becoming aware of areas for improvement

Your teachers will have obvious strengths but they will also have areas where they could improve. It is important to recognise and acknowledge the good performance of teachers – later in this unit you will do an activity to specifically address this. First, however, the focus is on tackling under-performance. This is where teachers are not employing the full range of skills, knowledge and behaviours associated with being an excellent teacher. To help you start thinking about this, read the case study below and complete the activity that follows it.

Case Study 1 Mr Prasad’s class’s exam results

The results of the first set of class tests of all subjects had come in. The school leader, Mr Kapur, sat with Mrs Agarwal, the most meticulous teacher to whom he had assigned responsibility for analysing exam and test results.

‘As usual,’ said Mrs Agarwal rather dramatically, ‘the students have performed really badly in science. I am sure this batch is going to bring down the results of the school!’

Mr Kapur was puzzled. He had taught these students in the previous year and had found they responded very well to challenge. The results did not match his memory of their capability.

‘Is it all the science subjects?’ he asked.

Mrs Agarwal studied his analysis in silence and then, looking up with a wry smile, said: ‘You’re a genius – it’s just biology. That’s Mr Prasad’s subject. I don’t think they like him too much. For one, he draws the most intricate diagrams with a beautifully steady hand and expects the students to copy it exactly in the same way. And of course, he still uses a foot-long scale to point at the labels!’

Mr Kapur nodded without responding. He certainly was not going to get pulled into discussing other teachers in the school.

‘Thank you, Mrs Agarwal. Now let’s look at their results in the social sciences,’ was all he said.

Activity 1: Recognising issues related to teacher’s performance

Mr Kapur used student results to help him to identify a teacher’s under-performance. Think about the ways that you might become aware of a teacher’s under-performance in your school. Write down three or four ideas in your Learning Diary.

In this case Mr Kapur was able to make links between poor results and teacher performance. There would not always be such direct links and it is important to look at other possible factors (e.g. illness, lack of access to textbooks, poor attendance patterns).

Every situation is unique, but here are some indicators that might suggest teacher performance issues:

- student absence is higher in one class

- students are frequently unruly in one class

- parents are unhappy about their child’s progress in one class

- students in a particular class do not appear to be progressing as well as expected

- teachers in the class above complain about the low level of attainment of one class

- students appear to be progressing less well in some subjects than in others.

2 Gathering evidence of performance

The important thing to bear in mind is that poor teacher performance is not necessarily related to whether a teacher approaches their teaching or organises their classroom in a different way from others. It is more that their teaching does not result in the progress normally expected of all their students at that time. It might be that the able students or the students from a particular cultural background do well but others do not, for example.

If you are not regularly gathering data on student learning by visiting classrooms or talking with teachers, you may not be aware of this under-performance until the students’ education is severely impaired. For this reason, regular monitoring is necessary and should be a routine part of your work. Through monitoring you will also recognise good performance and recognise the teachers who are performing well.

Figure 1 Gathering evidence through observation.

How might you gather evidence of performance? It is very important that action is taken based on evidence rather than anecdotes or guesses. However, an issue is usually raised from comparison with other teachers and their performance, so it is often necessary to gather evidence on more than one teacher or class.

Evidence-gathering needs to be deliberate and the process is ideally unbiased and balanced. Once you gather some initial data, you should seek out further information to clarify what exactly is going on. This might involve:

- gathering progress data from several classes

- personally observing teaching and learning

- talking to the students about their experiences. However, in this case, great care must be taken not to cast any doubt on the teacher’s ability by your questions and responses to the students’ answers.

It is also important to remember that it might be just one aspect of the teacher’s behaviour; it is not the teacher themselves that is the issue. You are not judging the person, you are judging their teaching behaviour – as explored in Activity 2.

Activity 2: What are you judging?

When looking at teacher competency, it is important to look at the teacher’s professional behaviour, not them as a person. Look at the list below and make a note in your Learning Diary about whether you think each item of evidence is about behaviour or the person:

- Observing a classroom for 20 minutes, noting down the number of different students that the teacher talks to.

- Comments from the students about the way that the teacher dresses.

- A report from a teacher that the teacher in the next door class always arrives ten minutes late for their lesson.

- Observing a classroom for 20 minutes, noting down how many open questions the teacher asks.

- Comments from the students about how they sometimes have different work from each other.

- Comments from parents that the teacher is from a different region.

Discussion

Some of these are not as clear as they first appear.

- Options 1, 4 and 5 are clearly about the way the teacher behaves.

- Option 2 is inappropriate and is clearly against the person, unless the dress is unmistakably unsuitable. Comments like this should be discouraged.

- Option 3 is similar, but you would need to be aware of potential bias and gather further evidence before acting.

- Option 6 could be blatant intolerance, but it could be that the teacher’s accent is so strong that the students find it difficult to understand. Again, there would need to be further investigation.

Now try Activity 3, which considers how you could gather evidence in your school.

Activity 3: How you could gather evidence in your school

If you were concerned about teaching in your school, think now about how you might gather evidence to understand more about the issue and what might be causing it. Make notes in your Learning Diary about the evidence you could gather and the issues you might have in gathering it.

Discussion

Clearly, we do not know what evidence you have decided upon. But the issues are likely to be similar:

- Teachers may be suspicious about your motives and unhappy about you entering their classroom.

- Students may act differently because of your presence.

- Parents may have concerns if students report your activity.

As you gather evidence in your school on a more regular basis, it will cause less excitement and concern – but initially, you will have to be reassuring. Gathering evidence from more than one teacher or class reduces the focus of attention for others to some extent. You can also think about involving the teachers by asking them what they would like feedback on as a way of making the process more collaborative.

It is particularly useful to share your concerns with other school leaders to see if they have any useful solutions to the potential problems or different forms of evidence.

3 Difficulties with gathering evidence

Now read the two case studies below, and complete their associated activities. They demonstrate how difficult it can be to gather evidence of poor performance.

Case Study 2: Mr Rawool’s review of students’ books

School leader Mr Rawool shared his difficulties in gathering evidence about the school’s teaching and learning practices with Mrs Chadha, his deputy who had just returned from sick leave. He reminded her that a day before she had reported sick, he had asked all the teachers to gather a sample of their students’ classwork and homework books. ‘It took two weeks of persistent requests before I could get them from everyone,’ he complained. ‘It would have been so much easier if I had just asked you to organise it. I think they do what you say more easily.’

Amused, Mrs Chadha asked him what he needed the books for. Mr Rawool said that he had been through the books and recorded whether the work had been checked and the sort of comments that students had received as feedback. Mrs Chadha asked if he had shared the reason he needed the books with the teachers. Mr Rawool confirmed he had.

‘Well, then,’ said Mrs Chadha. ‘It’s possible that they are worried about how you will use the information that you have gathered.’

Mr Rawool said he was aware of that, but didn’t want to take the books under false pretences. Mrs Chadha agreed with him that it would not be right to do that, but suggested that he could have started with a few of the more confident teachers. As word spread that the school leader’s discussions had been very useful and interesting, more teachers would have gathered the courage to bring their books to him. Mr Rawool nodded and said he saw the point: when introducing a new way of working, it would be better to begin with some teachers rather than wait for all of them.

‘Maybe I should take this advice now that I want to confirm what I found in the books by observing classes. I can start maybe by observing Mrs Chakrakodi’s class. She was the first one to give me the books of her students.’

Mrs Chadha agreed that Mrs Chakrakodi would be happy to have Mr Rawool in her class if she knew why he was coming in.

‘Maybe,’ she said thoughtfully, ‘it would be even better if you shared your students’ books with her and asked her to come observe you when you are teaching too!’

Mr Rawool laughed and said Mrs Chakrakodi would love that – and so would the other teachers! ‘You have some interesting ways of approaching difficulties,’ he complimented Mrs Chadha.

Figure 2 Gathering evidence.

Activity 4: Modifying how you gather evidence

Having read Case Study 2, would you change any of your plans or approaches in Activity 3? You might have realised that it is not so much about the evidence you gather as the way you go about gathering it – the way you inform people and how vulnerable you make them feel.

It is worth giving some thought to how you go about gathering evidence. You may want to think, for example, about how long you spend on your classroom observations – ten minutes is generally enough time to observe without being too disruptive to the teacher’s lesson.

Make a list in your Learning Diary of dos and don’ts for yourself when you start gathering evidence in your school.

Case Study 3: Mrs Vaidya analyses mathematics test scores

School leader Mrs Vaidya studied the test results for the mid-term examinations. She had heard about the staff room discussions about the performance of the students in mathematics. Mr Sharma, a mathematics teacher, had disparagingly declared that very few girls in Class XI understood mathematics and warned that trying to get the rest to pass the final examinations was going to be really difficult.

Mrs Vaidya could see why he was worried – the scores on the test of more than half the students were between 5 and 45 out of a 100. She then looked at the performance of the other classes in mathematics. Class IX had not done very well, but Classes X and XII had done better. She wondered if it was evidence that all of them were going to private tuition in preparation for the public examination at the end of the year; she would have to find out from the students.

Some patterns started becoming evident to her. For instance, the top scorers in each of the classes were clearly very good. Their scores clustered between 90 and 100 out of a 100. Then there was a visible gap in scores between 80 and 90. Almost a fifth of the class had scored between 60 and 80, and then another fifth between 40 and 60.

She picked up her green highlighter and began to identify the students doing well. She used red for the students who had scored less than 35 out of 100. She was going to have an important conversation with a mathematics teacher and she was sure she would need very strong numerical data. Along with the numbers, she also profiled the weaker students who were in the last category. Then, with the assistance of the teachers, she would identify the areas where students were weak, as well as those where they were strong. This background work would help her structure the after-school programme for the weaker students. She had seen the difference that doing this had made for the science papers; results in physics had already benefited from focused support in specific areas.

Activity 5: Gathering at least two types of evidence from more than one class

Drawing on some of the examples in Case Studies 2 and 3, gather at least two types of evidence on student learning from more than one class. Make sure you keep a copy of this evidence. This activity will help you start to monitor teacher performance in your school.

Make notes in your Learning Diary about any unexpected patterns you notice. As you make your notes, consider if you found the process easier or harder than you expected, and whether there were any issues you had not anticipated. Record your thoughts – these will be useful points to discuss with your colleagues if you have the opportunity.

Discussion

Again, we do not know what evidence you have collected or what unexpected patterns you have noted. However, it is important to remember that this is likely to be only part of an entire process of investigation. It is often the case that informal observations do not provide the whole picture – and even with two pieces of evidence, the picture is only partial.

4 Giving feedback

Gathering data can be a sensitive issue with your teachers; giving constructive feedback can be equally delicate. Although you may see a greater priority in giving feedback to an underperforming teacher, it is just as important to give positive feedback to the teachers who are doing well, so that they can know what you value in their working practices. This is vitally important in motivating your teachers and encouraging them to strive further. To be valuable to the teacher, your positive feedback should be specific and based on your observations, For example:

- ‘Your instructions to the students are very clear and then I noticed that you follow up with further advice while they are working in groups.’

- ‘I’ve noticed that you have new displays up in the classroom. I really think it encourages the students to feel pride in their work.’

- ‘I heard two students talking about your maths lesson in the corridor – they were grappling with a problem you had set and I could see that you had really inspired them.’

- ‘The test results for the girls in your class have risen by 25 per cent this year – congratulations!’

You may have more difficulty with giving less positive feedback – but when you base your feedback on evidence, this can help a great deal. Case Study 4 and Activity 6 look at the evidence-gathering process and how to offer feedback to an underperforming teacher. Both will help you to consider how to prepare for giving appropriate feedback.

Case Study 4: School leader Khan gathers evidence on a teacher

One Thursday the school leader, Mr Khan, was on his daily walk around the school. The previous Monday he had decided that during that week, he would gather evidence on the beginnings of classes. Two minutes before the bell rang for a change of lesson, he would take up his position at the far end of the corridor from which he could see all the activity in both corridors of classrooms. As the bell rang, he would watch teachers and students walk out of the classrooms they had been in and enter the classrooms where their new lesson was about to begin.

Today, Mr Khan was on the lookout for one person who he had noticed every day as the person who took a long time to get to class and then a long time to move out of it. It was Mr Mehta, the Hindi teacher. And like the other days, he watched as a teacher waited impatiently outside her class for five minutes until Mr Mehta emerged. Mr Khan watched Mr Mehta amble down the corridor. One of the classes he passed was the one he actually needed to go into, but he didn’t. He walked past it, straight to the staff room.

Five minutes later, Mr Mehta strolled out of the staff room in the direction of the class, which by now was so noisy that the neighbouring classes shut their doors to keep out the sound – despite this cutting off their ventilation.

Mr Khan followed Mr Mehta into class. He walked, as he usually did, to the back of the classroom, and the students made a place for him immediately. He glanced at a student’s book on the table in front of him – they were busy finishing the science homework for the next lesson. Mr Mehta began the class with an instruction that their Hindi homework should be submitted immediately. He then asked the students who had not submitted their homework to stand. Around half the class stood up. Mr Khan looked at his watch – it was 20 minutes into the lesson. Mr Mehta’s sermon to the students on the importance of homework was longer than usual. Mr Khan looked at the other students in class who had submitted their homework. He could see them getting restless and impatient. He quietly walked out of the class and made his way back to his room to prepare himself for a difficult conversation.

You may find Resource 1, ‘Monitoring and giving feedback’, useful. It has obvious parallels with this approach with your teachers.

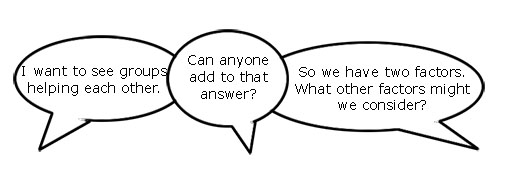

Figure 3 How will you give feedback to an underperforming teacher?

Activity 6: Giving feedback to an underperforming teacher

Think about how you would approach giving feedback to Mr Mehta. Make some notes on:

- how you would start the conversation

- the main points you want to raise.

Remember, it is a good idea to consider structuring your feedback that so you start with a positive and then end with a plan to improve matters. A positive target to focus on at the end can lead to an agreement about a follow-up meeting.

Discussion

There may be history to this observation that we are not told about in Case Study 4, such as previous high performance or a recent family bereavement; something that Mr Khan knows and would take account of in his feedback. We cannot plan now for any of those eventualities, but a very gentle opening is probably always advisable. Perhaps starting with ‘Tell me about the opening of the lesson that I observed the other day, ’ or similar, so that it is an opening for the teacher to explain why it was atypical or what was different about that day.

After the initial opening, the meeting might move to examining the observation in a little more detail – particularly if the teacher does not appear concerned about the opening of the lesson. The crucial point is the loss of learning time for these students. The lesson started late, it took time to settle and then there was the lecture about the homework, all taking valuable learning time. This might be an appropriate single focus for the feedback to the teacher: how to maximise learning time and the need to change the observed behaviour to allow this to happen.

You should note that there is no reason why you should not take time to plan your feedback when you talk with your own teachers. Feedback is a skill that develops over time and with practise, so making a few notes beforehand can really help you be specific.

Muralidharan and Sundararaman (2010) report on research where they found that it was not sufficient to simply provide feedback to teachers on their performance – even where this showed that their classes were not performing as well as other classes. The teachers changed their teaching behaviours in later classroom observation sessions, but no improvement was noted in student outcomes. They conclude that the teachers need much higher input, motivation or inducement to change their behaviour permanently.

One way to provide this higher input that has been shown to improve outcomes for students is to provide coaching to your teachers. You can learn more about coaching in the unit Developing your teachers: coaching and mentoring. You can also work with a teacher to develop a plan about how to develop new knowledge or skills. Activity 7 asks you to think about a plan of action that will be monitored.

Activity 7: Formulating a plan of action

Thinking of the research of Muralidharan and Sundararaman (2010) mentioned above, imagine you are Mr Khan from Case Study 4. Prepare a plan of actions on ways that you might work with Mr Mehta to enable him overcome his low performance in the classroom. Think about how this plan of actions will help the teacher in his development and how it can be monitored sensitively by you and by Mr Mehta himself. These case study activities are for you to practice skills that you can transfer to your own teachers and school setting.

Discussion

- This could be a chance to be creative. If Mr Mehta had a physical reason to return to the staff room between lessons, why not have a monitor who gave out worksheets or books at the start of the lesson, and have the students start before he joined them?

- Is it possible to set up some team teaching so that there is another teacher to provide good starts to the lesson? Would Mr Mehta benefit from some coaching or mentoring?

- The plan would have to include follow-up observations, clear targets and regular meetings with someone to discuss the progress.

In the next activity you are going to provide feedback to a teacher who is doing well. This might be a teacher about whom you earlier gathered evidence or it might be a new observation. Make sure that you use evidence in this activity and not assumptions based on the teacher’s good reputation.

Activity 8: Feedback for a teacher who is performing well

Consider a teacher that you have observed teaching an excellent lesson. Select a specific section of the lesson or a particular aspect of this teacher’s work that you thought was particularly good. Think carefully about the feedback that you want to give and reassure yourself that you have appropriate evidence to support that feedback.

In your feedback you need to:

- describe the activity or aspect to them

- explain why you judged the activity to be high in quality

- offer praise supported by evidence

- choose and use relevant criteria upon which to base your discussion.

Plan what you are going to say and plan the environment for the meeting. During the course of the meeting, you could go on to ask the teacher to reflect on how they might extend their good practice to others, or to other areas of their teaching.

Make notes in your Learning Diary after the meeting on how you think the feedback was received by the teacher. What behaviours did you observe to help you reach that conclusion? Also make notes on how you felt during and after the meeting. If you have colleagues you can trust, discuss this with them.

Discussion

Hopefully the meeting went well and your praise was well received. If this was the first such meeting you have arranged with a teacher in your school, both you and the teacher are likely to have been nervous. Conversations about performance are difficult even when they are positive. The criteria used are very important to keep the conversation on an objective, professional level. It is important that the feedback is on their performance, not on them as a person.

5 Evidence-gathering, feedback and teacher development as ongoing practice

Having worked through this unit, you will know that setting up the evidence-gathering, feedback and additional support for one teacher when poor performance has been noted is a very time-intensive and emotionally draining exercise.

Evidence-gathering, feedback and teacher development works best when it is part of ongoing practice. This reduces the chance of underperformance going unnoticed and can drive up the level of performance overall. It does not have to be the school leader who does all the evidence-gathering and feedback; it can be shared among the teachers as part of their development too.

Activity 9: Regular reviews of teaching

Draw up a plan for a regular review of one aspect of teaching within your own school. This might be about the start of lessons, setting homework or student–teacher relations.

There are many issues you could choose to focus on – you could use the key resources developed by TESS-India to help you to identify aspects of teaching that you want to review. You could use Resource 2, ‘Planning lessons’, as a handout for teachers or it may help you to decide what to look out for.

Make notes in your Learning Diary about why you chose that aspect of the teaching and perhaps also make a note of other aspects you might like to look at in the future and why.

Now read the case study that follows.

Case Study 5: SJ tracks her teachers’ progress

Sunita Jawahar (or SJ, as she is popularly known) meticulously maintained her school leader’s diary. She found it invaluable to look back over the year, mulling over the monthly targets she had set herself.

This month she had determined to look at the endings of classes. Her goals were to ensure that:

- teachers finish the lesson by summarising the content and outcomes

- the homework set at the end of the lesson is accessible and achievable by all students

- classes end on time.

These goals had been circulated to the teachers on an internal memo and it was made clear that this action was to improve the learning of all students. After all of the teachers’ signatures had been collected, it had been photocopied and pinned on the noticeboard in the staff room.

SJ had created a tracker to fill in during the week: a table that had five columns and seven rows. The first column’s heading was ‘Subject’ and under that were listed ‘Science’, ‘Social sciences’, ‘Mathematics’ and then each of the languages taught in the school. The remaining column headings referred to classes: ‘IXa’, ‘IXb’, ‘Xa’ and ‘Xb’.

The table had begun to fill up. She had walked into the Class IXb science lesson in the last ten minutes and completed her observation form, focusing only on her goals for the month. She had done the same for Classes Xa in English, IXb in Hindi and IXb in social sciences. This week, she planned to complete the observation of the remaining 20 classes and then put up the data in the staff room, in advance of the teachers’ meeting. She had planned the data so that it would be presented as a pie chart, without any names. However, she did have a plan on meeting the teachers who were unable to meet the goals, to ask them how she could support them to achieve the targets.

One of them had already come in to discuss the lesson plan with her – and they had worked together to improve the way the lesson could be conducted. The IXb Hindi lesson by Mrs Nagaraju had been planned really well and the lesson summary had been clear, with students identifying their learning. Mrs Nagaraju had been delighted with the feedback, but it had taken a bit of encouragement before she had agreed to be a role model for other colleagues. SJ gave herself a little star on the corner of the day’s page – her plan was working. She was determined that by the end of the month, all three goals would be met.

It was then that she realised she hadn’t thought of how she would celebrate the achievement with her staff! Her plan was incomplete. She made the final diary entry for the day: ‘My homework: think about how to get feedback from the students on the usefulness of the lesson summary, and how the feedback can be collated and reported to the teachers.’

Activity 10: Reviewing your plan

Having read Case Study 5, have another look at your own plan and consider how you might want to change it. Discuss your idea with two of your teachers and see if you wish to change it further before implementing it.

Make notes in your Learning Diary about their response to the suggested activity and as a result think about how you might introduce it to your whole staff.

6 Summary

Students have the right to expect excellent teaching, but do not always receive it. There can be a range of reasons for this, and one of those – teacher performance – is within the remit and ability of a school leader to influence.

However, this will only happen in an organisation where levels of trust are high. Individuals must feel valued and know that it is their teaching behaviour, rather than them personally, that is being judged – otherwise it will lead to bad feeling and antagonism. This is why it is important to get practice at providing positive feedback before the more difficult areas are tackled.

The more regularly a teacher’s classroom behaviour is reflected upon, drawing on objective evidence, the less likely it is that their performance will drop to a level described as poor – particularly where supportive development activities are planned. To establish a culture in the school where observation and performance discussion are the norm may take a long time – over a year, perhaps. So although it may be hard at the beginning and you may meet some resistance, persevere, but with sensitivity and fairness.

This unit is part of the set or family of units that relate to the key area of transforming teaching-learning process (aligned to the National College of School Leadership). You may find it useful to look next at other units in this set to build your knowledge and skills:

- Leading improvements in teaching and learning in the elementary school

- Leading improvements in teaching and learning in the secondary school

- Leading assessment in your school

- Leading teachers’ professional development

- Mentoring and coaching

- Developing an effective learning culture in your school

- Promoting inclusion in your school

- Managing resources for effective student learning

- Leading the use of technology in your school.

Resources

Resource 1: Monitoring and giving feedback

Improving students’ performance involves constantly monitoring and responding to them, so that they know what is expected of them and they get feedback after completing tasks. They can improve their performance through your constructive feedback.

Monitoring

Effective teachers monitor their students most of the time. Generally, most teachers monitor their students’ work by listening and observing what they do in class. Monitoring students’ progress is critical because it helps them to:

- achieve higher grades

- be more aware of their performance and more responsible for their learning

- improve their learning

- predict achievement on state and local standardised tests.

It will also help you as a teacher to decide:

- when to ask a question or give a prompt

- when to praise

- whether to challenge

- how to include different groups of students in a task

- what to do about mistakes.

Students improve most when they are given clear and prompt feedback on their progress. Using monitoring will enable you to give regular feedback, letting your students know how they are doing and what else they need to do to advance their learning.

One of the challenges you will face is helping students to set their own learning targets, also known as self-monitoring. Students, especially struggling ones, are not used to having ownership of their own learning. But you can help any student to set their own targets or goals for a project, plan out their work and set deadlines, and self- monitor their progress. Practising the process and mastering the skill of self-monitoring will serve them well in school and throughout their lives.

Listening to and observing students

Most of the time, listening to and observing students is done naturally by teachers; it is a simple monitoring tool. For example, you may:

- listen to your students reading aloud

- listen to discussions in pair or groupwork

- observe students using resources outdoors or in the classroom

- observe the body language of groups as they work.

Make sure that the observations you collect are true evidence of student learning or progress. Only document what you can see, hear, justify or count.

As students work, move around the classroom in order to make brief observation notes. You can use a class list to record which students need more help, and also to note any emerging misunderstandings. You can use these observations and notes to give feedback to the whole class or prompt and encourage groups or individuals.

Giving feedback

Feedback is information that you give to a student about how they have performed in relation to a stated goal or expected outcome. Effective feedback provides the student with:

- information about what happened

- an evaluation of how well the action or task was performed

- guidance as to how their performance can be improved.

When you give feedback to each student, it should help them to know:

- what they can actually do

- what they cannot do yet

- how their work compares with that of others

- how they can improve.

It is important to remember that effective feedback helps students. You do not want to inhibit learning because your feedback is unclear or unfair. Effective feedback is:

- focused on the task being undertaken and the learning that the student needs to do

- clear and honest, telling the student what is good about their learning as well as what requires improvement

- actionable, telling the student to do something that they are able to do

- given in appropriate language that the student can understand

- given at the right time – if it’s given too soon, the student will think ‘I was just going to do that!’; too late, and the student’s focus will have moved elsewhere and they will not want to go back and do what is asked.

Whether feedback is spoken or written in the students’ workbooks, it becomes more effective if it follows the guidelines given below.

Using praise and positive language

When we are praised and encouraged, we generally feel a great deal better than when we are criticised or corrected. Reinforcement and positive language is motivating for the whole class and for individuals of all ages. Remember that praise must be specific and targeted on the work done rather than about the student themselves, otherwise it will not help the student progress. ‘Well done’ is non-specific, so it is better to say one of the following:

Using prompting as well as correction

The dialogue that you have with your students helps their learning. If you tell them that an answer is incorrect and finish the dialogue there, you miss the opportunity to help them to keep thinking and trying for themselves. If you give students a hint or ask them a further question, you prompt them to think more deeply and encourage them to find answers and take responsibility for their own learning. For example, you can encourage a better answer or prompt a different angle on a problem by saying such things as:

It may be appropriate to encourage other students to help each other. You can do this by opening your questions to the rest of the class with such comments as:

Correcting students with a ‘yes’ or ‘no’ might be appropriate to tasks such as spelling or number practice, but even here you can prompt students to look for emerging patterns in their answers, make connections with similar answers or open a discussion about why a certain answer is incorrect.

Self-correction and peer correction is effective and you can encourage this by asking students to check their own and each other’s work while doing tasks or assignments in pairs. It is best to focus on one aspect to correct at a time so that there is not too much confusing information.

Resource 2: Planning lessons

Why planning and preparing are important

Good lessons have to be planned. Planning helps to make your lessons clear and well-timed, meaning that students can be active and interested. Effective planning also includes some in-built flexibility so that teachers can respond to what they find out about their students’ learning as they teach. Working on a plan for a series of lessons involves knowing the students and their prior learning, what it means to progress through the curriculum, and finding the best resources and activities to help students learn.

Planning is a continual process to help you prepare both individual lessons as well as series of lessons, each one building on the last. The stages of lesson planning are:

- being clear about what your students need in order to make progress

- deciding how you are going to teach in a way that students will understand and how to maintain flexibility to respond to what you find

- looking back on how well the lesson went and what your students have learnt in order to plan for the future.

Planning a series of lessons

When you are following a curriculum, the first part of planning is working out how best to break up subjects and topics in the curriculum into sections or chunks. You need to consider the time available as well as ways for students to make progress and build up skills and knowledge gradually. Your experience or discussions with colleagues may tell you that one topic will take up four lessons, but another topic will only take two. You may be aware that you will want to return to that learning in different ways and at different times in future lessons, when other topics are covered or the subject is extended.

In all lesson plans you will need to be clear about:

- what you want the students to learn

- how you will introduce that learning

- what students will have to do and why.

You will want to make learning active and interesting so that students feel comfortable and curious. Consider what the students will be asked to do across the series of lessons so that you build in variety and interest, but also flexibility. Plan how you can check your students’ understanding as they progress through the series of lessons. Be prepared to be flexible if some areas take longer or are grasped quickly.

Preparing individual lessons

After you have planned the series of lessons, each individual lesson will have to be planned based on the progress that students have made up to that point. You know what the students should have learnt or should be able to do at the end of the series of lessons, but you may have needed to re-cap something unexpected or move on more quickly. Therefore each individual lesson must be planned so that all your students make progress and feel successful and included.

Within the lesson plan you should make sure that there is enough time for each of the activities and that any resources are ready, such as those for practical work or active groupwork. As part of planning materials for large classes you may need to plan different questions and activities for different groups.

When you are teaching new topics, you may need to make time to practise and talk through the ideas with other teachers so that you are confident.

Think of preparing your lessons in three parts. These parts are discussed below.

1 The introduction

At the start of a lesson, explain to the students what they will learn and do, so that everyone knows what is expected of them. Get the students interested in what they are about to learn by allowing them to share what they know already.

2 The main part of the lesson

Outline the content based on what students already know. You may decide to use local resources, new information or active methods including groupwork or problem solving. Identify the resources to use and the way that you will make use of your classroom space. Using a variety of activities, resources, and timings is an important part of lesson planning. If you use various methods and activities, you will reach more students, because they will learn in different ways.

3 The end of the lesson to check on learning

Always allow time (either during or at the end of the lesson) to find out how much progress has been made. Checking does not always mean a test. Usually it will be quick and on the spot – such as planned questions or observing students presenting what they have learnt – but you must plan to be flexible and to make changes according to what you find out from the students’ responses.

A good way to end the lesson can be to return to the goals at the start and allowing time for the students to tell each other and you about their progress with that learning. Listening to the students will make sure you know what to plan for the next lesson.

Reviewing lessons

Look back over each lesson and keep a record of what you did, what your students learnt, what resources were used and how well it went so that you can make improvements or adjustments to your plans for subsequent lessons. For example, you may decide to:

- change or vary the activities

- prepare a range of open and closed questions

- have a follow-up session with students who need extra support.

Think about what you could have planned or done even better to help students learn.

Your lesson plans will inevitably change as you go through each lesson, because you cannot predict everything that will happen. Good planning will mean that you know what learning you want to happen and therefore you will be ready to respond flexibly to what you find out about your students’ actual learning.

Additional resources

- Teaching poetry at GCSE: http://www.youtube.com/ watch?v=vZgvHmviq-U

- Primary talk and success criteria: http://www.youtube.com/ watch?v=1v2QbW3_Ai4

- Learning to teach (OpenLearn unit): http://www.open.edu/ openlearn/ learning-teach/ content-section-0

References

Acknowledgements

This content is made available under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike licence (http://creativecommons.org/ licenses/ by-sa/ 3.0/), unless identified otherwise. The licence excludes the use of the TESS-India, OU and UKAID logos, which may only be used unadapted within the TESS-India project.

Every effort has been made to contact copyright owners. If any have been inadvertently overlooked the publishers will be pleased to make the necessary arrangements at the first opportunity.

Video (including video stills): thanks are extended to the teacher educators, headteachers, teachers and students across India who worked with The Open University in the productions.