Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Friday, 27 February 2026, 9:25 PM

TI-AIE: Transforming teaching-learning process: leading teachers’ professional development

What this unit is about

The National Curriculum Framework for Teacher Education: Towards Preparing Professional and Humane Teacher (NCFTE) (National Council for Teacher Education, 2009) emphasises the importance of developing a professional workforce. Professional development is a lifelong process and is a key element in developing professionalism. The District Primary Education Programme (DPEP) and Sarva Shiksha Abhiyan (SSA) have put into place a number of sites to provide professional development to all public sector school teachers through block and cluster resource centres. In addition, the Institutes of Advanced Studies in Education (IASEs), Colleges of Teacher Education (CTEs), the State Council of Educational Research (SCERT), District Institutes of Education and Training (DIETs) and some non-governmental organisations (NGOs) conduct in-service training programs for teachers. Development takes place not only through in-service training but through instructor-led workshops, Cluster Resource Centre (CRC) meetings, conversations in the corridor, peer coaching, group learning activities, etc.

As a school leader your leadership role implicitly includes providing support to teachers to enable them improve their practice (including leading teacher professional development). This is not straightforward because there are certain constraints (including budgets) that are not within your control. However, there are opportunities for you to maximise teachers’ effectiveness through school-based support strategies, which is the focus of this unit.

Learning Diary

During your work on this unit you will be asked to make notes in your Learning Diary. If you have not already started one, this is a book or folder where you can document thoughts and plans together in one place.

You may be working through this unit alone but you will learn much more if you are able to discuss your learning with another school leader. This could be a colleague with whom you already collaborate, or someone with whom you form a new relationship. It could be through an organised activity or on a more informal basis. Notes you make in your Learning Diary will be useful for this, as well as mapping your learning and development.

What school leaders can learn in this unit

- How teachers’ professional development can impact on school improvement and student learning outcomes.

- Some ideas to help your teachers assess their professional development needs.

- Plan, monitor and enable professional development of all teachers.

1 Perspectives on teacher development

Teaching is not a static profession but one that changes with the influence of technology, the ever-changing body of knowledge, pressures of global economics and social pressures. This means that ongoing updating and development of teaching approaches and skills is needed to address these changes. Having the ability to change is essential for teachers.

In order that the pedagogic vision in the National Curriculum Framework (NCF, 2005) is realised by teachers in our classrooms, it is important that the professional development of teachers takes place with the onus of responsibility falling on the school leader. Key Area 3 of the National Programme Design and Curriculum Framework (2014) focuses on transforming the teaching–learning process into child-centred creative engagement by developing the capabilities of school leaders. The school leader thus has a critical role in planning, monitoring and enabling the continuous professional development (CPD) of every teacher in their school.

Christopher Day (1999) argues that teachers’ professional development should be seen as a lifelong activity that focuses on both their personal and professional lives, and on the policy and social context of the workplace. This is an important consideration for the school leader, as the teachers will always be learning just as the students will always be learning. There is no end point when all knowledge and skills have been acquired.

Figure 1 Teachers discussing development needs.

While professional development often exists in centralised courses, school-based professional development offers many benefits and can help overcome barriers to teachers engaging with their professional development that centralised courses cannot offer; for example, by:

- addressing the professional development needs of the individual teacher

- addressing the specific needs and characteristics of the school

- fitting in with the specific focuses for development of the school

- making it easier to build capacity and skills by getting a group of teachers working together

- being less disruptive to teaching timetables, as teachers can work on their professional development while teaching

- providing the possibility of immediate feedback on student learning, as the professional development can take place in the classroom

- giving school leaders more control over the quality and focus of the professional development.

This unit focuses on in-service teacher development through school-based activities that promote effective learning and teaching as well as wider school improvement.

The next activity aims to help you think about identifying what changes in teaching practice may be required and choosing between professional development courses or in-school professional development, using NCFTE (2009) as guidance.

Activity 1: Review of NCFTE (2009)

Chapter 3 (‘Transacting the curriculum and evaluating the developing teacher’) of the NCFTE (2009) identifies current practice in teacher education and how this could become more process-based. Take a look at some of the characteristics identified in the NCFTE which are described below in Figure 2. Mark on the continuum line where you feel your school mostly operates in relation to the development of teachers: Is it mostly to the left or mostly to the right? Remember to focus on the teachers as the learners, not the students, when you do this activity.

| Theory as a ‘given’ to be applied in the classroom | _____________________ | Conceptual knowledge generated, based on experience, observations and theoretical engagement

|

| Knowledge treated as external to the learner and something to be acquired | _____________________ | Knowledge generated through critical enquiry in the shared context of teaching, learning, personal and social experiences

|

| Learners work individually on assignments, in-house tests, field work and practise teaching | _____________________ | Learners encouraged to work in teams, undertaking classroom and learners’ observations, interaction and projects across diverse courses; group presentations encouraged

|

No ‘space’ to address learners’ assumptions about social realities, the learner and the process of learning

|

_____________________ | Learning ‘spaces’ provided to examine learners’ own position in society and their assumptions as part of classroom discourse |

No ‘space’ to examine learners’ conceptions of subject knowledge

|

_____________________ | Structured ‘space’ provided to revisit, examine and challenge (mis)conceptions of knowledge |

Footnotes

Figure 2 NCFTE characteristics on a continuum.Discussion

This activity aimed to help you to start thinking about how far your school currently works towards the practices highlighted and advocated in NCFTE (2009) to make ‘reflective practice the central aim of teacher education’ and to recognise that ‘[pedagogical knowledge has to constantly undergo adaptation to meet the diverse needs of diverse contexts through critical reflection by the teacher on his/her practices’ (pp. 19–20). Ideally your marks should all end up on the left-hand side where learning is active and interactive. The reality may be that your marks are on the right or in the middle. This gives you a direction in which to travel (and discuss).

As a school leader you are responsible for school improvement and thus for student learning outcomes and staff development. Ideally, you will be working with your teachers to develop their knowledge through their daily experience of teaching in a way that encourages your teachers to share their knowledge and skills with an openness that also allows them to observe each other and discuss issues together in a number of curriculum sites (farm, workplace, home, community and media).

To facilitate this, as a school leader, you will need to create the appropriate safe ‘spaces’, where teachers feel they can share their experiences, and where experimenting is encouraged and ideas are valued.

2 Teachers’ professional learning and development

Professional learning and development (PLD) is about an individual’s ability to acquire knowledge and skills related to their work or practice, or to look for information and keep themselves well informed in their professional field.

According to the National Council for Teacher Education (NCFTE, 2009, pp. 64–5), the broad aims for PLD of teachers are to:

- explore, reflect and develop one’s own practice

- deepen one’s knowledge of and update oneself about one’s academic discipline or other areas of school curriculum

- research and reflect on learners and their education

- understand and update oneself on educational and social issues

- prepare for other roles professionally linked to education/teaching, such as teacher education, curriculum development or counseling

- break out of intellectual isolation and share experiences and insights with others in the field, both teachers and academics working in the area of specific disciplines as well as intellectuals in the immediate wider society.

SCERT works with DIETs to provide most (if not all) of the official PLD for teachers. This usually takes place at specially organised workshops that require personal attendance. The training can be problematic as it can only ever address general issues and very often serves primarily as an information outlet for new policy initiatives and interventions.

The skill levels and development needs of your teachers will vary. Their differing motivations and characteristics will also mean that you will need to use different approaches to encourage them to engage with PLD on an ongoing basis. The example of Mrs Gupta (below) shows someone who obviously has some PLD needs but who may also be reluctant to engage. Mrs Gupta may remind you of someone you know. This case study will be used in Activity 3.

Case Study 1: Mrs Gupta’s teaching

Mrs Gupta has been a teacher for 16 years at the same elementary school. She takes great pride in her displays, bringing paper from home and having a special box with scissors, glue, stencils and drawing pins. She has the best displays in her classroom, organising them with two ‘able’ girls. The parents and other visitors often comment on the displays when they visit. She takes great pride in receiving such praise.

Generally, Mrs Gupta likes her work but there are some chapters in the science textbook that she does not like to teach because she is unsure of the theory and content. Sometimes she gets a bit bored with teaching but in general she likes the contact with the students, especially the bright ones whom she asks to sit at the front of the class; she is not ashamed of having her ‘favourites’. She does not pay as much attention to the less able students, at the back of the class, and is relieved when poor attendance at harvest times means that there are fewer students to deal with.

Mrs Gupta has occasionally attended training workshops at the DIET, but tends to avoid these if possible. She does not like travelling or going to places where there are people she does not know. She is supportive to other colleagues on a personal level but does not really engage in conversations about teaching practice or in wider discussions about school improvements. She simply comes to school to teach her class and then goes home to look after her family. She used to be a keen dancer in her spare time; she now runs dancing lessons privately once a week at another school. One year she organised a dance display with the final year students, but feels now that this is just too much work to take on alone.

Activity 2: Planning for a conversation about professional development

Consider how you, as the school leader, could have a conversation with Mrs Gupta to introduce the idea of CPD. Obviously, you do not know Mrs Gupta, but you may know other teachers like her. Imagine talking to her about her strengths and how she could develop as a teacher. Make notes in your Learning Diary.

- How could you start a discussion about her development needs?

- What strengths could you focus on, as well as her weaknesses?

- How do you think she could react?

- What actions could you take to achieve a positive outcome?

Look at the template in Resource 1. Consider how it could be used in relation to Mrs Gupta. What types of issues and ideas could arise and in which sections would you record the comments?

You may also find it useful to look at Resource 2, ‘Storytelling, songs, role play and drama’, which concerns alternative methods that can be used in teaching – Mrs Gupta is obviously a very creative person and the students could stand to benefit a great deal from her creativity if it was used more in their lessons. The key resources that accompany these Open Educational Resources (OERs) focus on different topics and can be useful tools in discussions about PLD. You will come back to these notes in the next activity, when the focus moves to planning PLD activities.

Discussion

It may be that the culture in your school means that you already have regular professional reviews or appraisals where you discuss with your staff, individually, their professional practice and identify the focus for their future professional development. Your teachers may therefore be accustomed to these types of conversations. However, it is highly probable that they may be having such a conversation with you for the first time.

To better understand your teachers’ professional lives it will be very useful to prepare a meeting schedule with every teacher to discuss their support needs, interests and expectations. This should be a professional conversation but conducted in a non-threatening way, allowing a useful discussion that helps you to learn about your teachers’ professional lives. It may be that someone like Mrs Gupta would need some coaxing and reassurance to engage in the conversation, but there are strengths that you could identify that may open the door for communication. These initial conversations and the records should serve as a basis for future support and planning of development activities: they are the start of ongoing conversations that will, ideally, aim to make the teachers take responsibility for their own development.

The conversations can be linked with any observations of lessons you have done, or other monitoring processes you may have undertaken.

With time, a school may introduce peer observation and lesson review as a regular part of the PLD cycle, with colleagues contributing to the evidence that is used in appraisal conversations.

3 Models of teachers’ PLD

Although, PLD is often structured and managed, it can take place both formally and informally. It can happen individually, in small groups or on a larger scale, and can include approaches such as action research, reflection on practice, mentoring and peer coaching. It is important to value and recognise informal learning in your school as well-structured training programmes to ensure that the full range of development opportunities are used.

Information and communications technology (ICT) – including TV, radio and the Internet – is useful for providing access to knowledge, or for wider dissemination of important and new information. ICT will help your teachers to engage with relevant experts and also to access information. The internet provides an opportunity for you and your staff to harness free resources (many of which are delivered online as OERs, including TESS-India) and the National Repository of Open Educational Resources (NROER), coordinated by the Central Institute of Educational Technology (CIET) in the National Council of Educational Research and Training (NCERT), to feed into professional development in your school. Links to these online resources can be found at the end of this unit.

PLD activities in classrooms should be the primary vehicle for improving teaching and learning. It is vital that teachers are given the time and space to reflect on and improve their classroom practice. However, all teachers, no matter how effective they are, will also learn much from observing good practice of others. This may often be available in the school but may be ‘invisible’ in that staff may not know whom to observe or which practice they may benefit from. In this way the leadership role can often involve being a conduit to help make ‘invisible’ good practice more visible to the staff community, and therefore valuable to others. This requires you to understand where good practice exists in the school and being able to use this for the benefit of the whole teaching community. The first step in this process is to help every individual teacher become an effective learner about their practice and feel empowered to take steps to improve it.

There are several ways that teachers can learn in the classroom, all of which are underpinned by situated learning – where the teacher tries out something new or adapts something that they already do. Teachers need to have enough confidence to try out new ideas for themselves, accepting that sometimes this will go wrong; they then need to have the opportunity to reflect upon what happened and why it went wrong, so that they can further modify their practice. Situated learning can take place and be supported in a number of ways; listed below.

School-based PLD activities

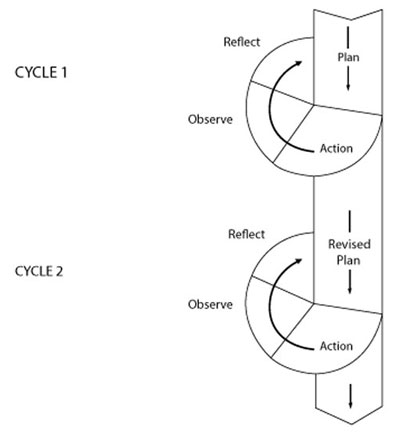

- Action research, where the teacher decides to explore a specific area of interest or concern, tries a new approach in the classroom to develop their practice, reflects on the impact on student learning, and then reviews what needs to happen next. Action research is cyclical, as the final phase of identifying next steps provides the impetus for exploring the next new idea (see Resource 3).

- Collaborative learning, where the teacher will engage with other teachers to learn together by comparing and contrasting, sharing practice, and developing plans. This should be convened to address a particular aspect of practice (e.g. a working group to look at assessment across the school).

- Team teaching, where two teachers work together to deliver a lesson or sequence of lessons using their combined skills to enhance variety, pace, student focus, novelty and demonstration, and learn from each other or try out new approaches together.

- Reflecting on practice, which can be a solitary activity but can equally be shared with others with reflections prompted and probed by questions from a colleague or in a group. An important opportunity for prompting reflection is the discussions that follow lesson observations by colleagues.

- Participation in teacher networks, school-based networks and school-twinning partnerships are other ways of encouraging your teachers to share their experiences, discuss problems, be exposed to ideas by their peer group, and reflect and plan for the future. You could explore this with other school leaders who are responsible for schools close to yours.

The TESS-India subject units provide many opportunities for teachers to work together or individually on different aspects of their teaching and of student learning. The TESS-India key resources also provide excellent reference points for development activities on the following topics:

- assessing progress and performance

- monitoring and giving feedback

- storytelling, songs, role play and drama

- using local resources

- using pair work

- using groupwork

- planning lessons

- using questioning to promote thinking

- talk for learning

- involving all.

You will notice that in all these examples of learning, the teacher (either alone or together with colleagues) identifies the area of development and is then actively involved in planning and engaging in the learning. In other words, it is not something that is done to them, but something that empowers them to improve themselves. This does not mean that as a leader you do not have an opportunity to highlight or suggest developmental needs, but this must be done in a spirit of cooperation and collaboration in learning together. As a school leader you act as an enabler of others’ learning, both teachers and students.

Activity 3: Identifying learning opportunities

Following on from your consideration of Mrs Gupta in Activity 2, use the five types of PLD learning above to identify PLD activities that Mrs Gupta could undertake. You may want to think about options for her active learning, reflection on practice, individual learning, learning as part of a group learning, and/or coaching by a peer or school leader. Do not feel constrained by the limited amount of information you have for the case study: you can add to it when you suggest ways she could develop, or she may remind you of a colleague, so you could do this activity with that person and your own school in mind.

Make some notes in your Learning Diary about a suitable activity.

Discussion

You have probably thought about a range of opportunities for Mrs Gupta to develop her skills at the school. For example, you might have suggested that she observe a more confident teacher, teach those difficult science lessons, or that she be coached on the content by the science teacher to fill any knowledge gaps. You might also have suggested that the school should have a dance week next term when lessons are geared around this theme (anatomy, literature, geometry, music, etc.) and ask Mrs Gupta to take a lead in this. In addition, you may decide to observe one of Mrs Gupta’s lessons and then report back to her on the different levels of engagement between pupils at the front and back of the class.

The conversation about the challenges and solutions of multilevel classes could be widened to the cover all staff in the group, being a development opportunity for all. Mrs Gupta could refresh and strengthen her teaching practice and enhance her students’ learning as part of her school day, using colleagues around her, whether learning by doing or finding her own solutions. You might also have noted that Mrs Gupta is very good at making displays and that there may be roles for her in helping other teachers to develop these skills. The key is her motivation and this is why it is important to work together with Mrs Gupta on identifying needs and making a plan to meet them – she will engage more enthusiastically if she is involved in the discussions about her strengths and needs and agrees on priorities and opportunities.

Mrs Gupta may be a particularly challenging teacher to work with as she is well established at the school and so not necessarily interested in her PLD. But she has genuine strengths that are an asset for the school and need to be valued. The conversation about her PLD should be balanced between building on strengths and addressing needs – and not all needs have to be addressed at once.

You will have many teachers who embrace the chance to learn and improve and who will welcome your interest in their PLD.

Activity 4: Formulate an action plan

As a school leader you have worked on identifying the needs and opportunities for Mrs Gupta. Now you need to turn your attention to your own staff and school. Work with one or two teachers who are likely to be enthusiastic about their PLD and motivated by your interest in helping them. For each teacher, go through the process identified in Activity 2 (using the template in Resource 1) and Activity 3 (identifying the opportunities), and then work with each of them to formulate a plan. Resource 4 has a template that you can use for the planning.

Do not set too many actions; a maximum of four or five would be ideal. Do not make them too complex as you will need to be able to organise this alongside all your other responsibilities. Remember that PLD is a continual process and therefore your teachers can develop year-on-year.

You may like to have a session at a staff meeting where you introduce the idea and ask for volunteers for the first PLD discussions, or you may do this informally. But either way, you need to have a plan as to how you will roll out a system of PLD to all staff in your school. You may find your two volunteers helpful in taking this forward. There must be an element of challenge in the plan you devise, so that it stretches the ability of the teacher and therefore carries them on to new ground. But the plan must also be attainable and viable within a realistic time frame. It is essential that each target is underpinned with the goal of improving learning outcomes for all students.

Discussion

Once such a procedure has been incorporated into the school’s usual practice, the whole notion of PLD will embed itself, and everyone in the school will then see themselves as co-learners. With a general understanding of PLD in your school, you may be able to delegate the discussions to pairs or groups to find the opportunities, so developing a culture of sharing of expertise and co-development. If every member of staff, not just the teachers, can be involved in their own development, the students will also see how important it is to learn throughout their lives. It changes the ethos of the school.

4 Keeping a record of development activities

As a school leader it is important to keep records of the development activities of your staff. This is evidence of your commitment to improving learning for students through supporting and enhancing the performance of staff. By using recording sheets like those suggested in the resources section, as well as records of attendance on training days, you will not only keep track of each teacher’s progression, but also of actions you have taken in relation to school improvement.

It is also the responsibility of each teacher to keep their own records of their development. This has often been just a list of courses attended with dates, but it does not necessarily include records of in-school PLD activities that they have engaged in. Keeping a Learning Diary or portfolio is one way of doing this. Doing so means not only that a teacher can track their own progress, but they can draw on their records to evidence their improving practice and demonstrate their commitment to professional development.

Read the case study below about how one teacher keeps records of his professional development and how he not only uses these records as part of his reflective process, but also as a way of remembering and reviewing. He makes notes of his ideas most days and can draw on his records when he needs to present evidence of his PLD to others.

Case Study 2: Mr Kapur keeps a record of his school-based PLD

Mr Kapur loves teaching. His father and his aunt were teachers and he felt it was in his blood to teach. After qualifying he began teaching in a medium-sized school in a poor urban area. Two years in, he felt that he needed some new ideas, but although his students seemed to be enthusiastic and motivated in his lessons, he felt he had put into practice everything that he had learned on his teaching course.

Mr Kapur talked to his school leader, who suggested three PLD activities that he could undertake at the school. First, to observe and learn from the science lessons of Mr Farooqi, who was widely recognised as an excellent teacher; second, to follow up on his idea to link mathematics and sports lessons as a way of inspiring the boys to engage in mathematics; and, third, to pass on his knowledge and skills by mentoring a new teacher who would be joining in the next term. Mr Kapur agreed that these were all useful. A brief plan was agreed, which was placed on Mr Kapur’s file, as well as in his notebook.

When Mr Kapur went to Mr Farooqi’s lesson, he made notes of his observations and of the discussion he had afterwards with Mr Farooqi about how he had planned and delivered the lesson. In his notes, Mr Kapur added some suggestions about how he could apply some of what he had learned to his own lessons; two weeks later he repeated one of the activities he had seen in a science lesson, and made notes about how it went. He was careful to date each entry but did not bother if the notes were tidy or legible to others – if he needed to write this up at any time, he would work from his notes.

Mr Kapur was pleased that the school leader had liked his idea about linking mathematics and sport, so he spent several evenings reading the curriculum and mathematics textbook. He also looked online for any research or practice in the area, and talked to a couple of colleagues at work about his ideas – whose suggestions were very helpful. Mr Kapur wrote some notes on his developing ideas. He tried out a few activities with his class and asked for some feedback from his students, which he kept for future reference. Eventually he wrote a paper for the staff group to explain how this approach may work, and received positive feedback, which he recorded and kept. Several months on, there are now two other teachers using Mr Kapur’s approach.

Before Mr Kapur started mentoring the new teacher, he consulted books and the internet for best practice in mentoring, as he wanted to mentor correctly. He discovered the online TESS-India unit Transforming teaching-learning process: mentoring and coaching: he found it useful to be able to learn without travelling to attend a course in person. As he mentored he kept his own notes about what he did and what he could have done better. He found it helpful to reflect on his mentoring, which meant that he was better able to talk about the experience with the school leader when he asked.

The records that Mr Kapur kept were for his eyes only and largely informal – he started them in his first year as a teacher and continued this practice. He found it helpful to look back to see how he had developed, but also to remind himself of what else he could do to be a better teacher. When he applied for another job and needed to refresh his CV and prepare for the interview, his notes were invaluable.

Activity 5: Organising your own records

If you have studied the TESS-India unit Managing and developing self: managing and developing yourself, you will have started to think about how your own PLD runs in parallel with that of your teachers. Now think about how you keep records of your own PLD as a school leader. Are you as organised as Mr Kapur? Using the case study, write down a list of the types of records he kept (e.g. a plan, some ideas, a list) and then a list of what he used them for. This may help you think about the kind of notes you may keep of your own PLD.

If you are keeping a Learning Diary, you are getting into this practice whilst studying this unit. A good school leader models the practice that they wish to see in their staff. If you do not already have a notebook or file to record your development, you should create one.

Take a few minutes now to consider the realities of your busy and demanding working day and make notes in response to the following questions:

- What could conspire against you from keeping your own PLD records?

- What will you do to stop things getting in the way?

- How you are going to record your own PLD activities and reflections (daily, weekly, the format)?

You should also set yourself a review date (maybe one or two months away) to check on your records.

Having the discipline to keep PLD records will remind you of your progress and provide you with a way to reflect about your challenges and opportunities. The records will also give you a source of data to demonstrate your PLD and to share your expertise. You will need to lead by example if you are going to require your teachers and students to become active; they themselves are continual learners. Data on the PLD of staff at the school provides evidence of the school’s commitment to continuous improvement and the raising of standards.

5 Systematising PLD in your school

So far this unit has assumed that PLD may not be well established in your school and suggests some minor ways to get it started. But you should be aiming for a systematised process of CPD for all staff at all levels in your school. Every member of the school community is part of a learning institution and should therefore engage with their personal development, demonstrating to students that learning is a lifelong process.

If PLD occurs regularly and is seen as a normal activity in a school, it becomes a natural process for teachers to share their own best practice, access formalised development programmes, and, of course, to develop themselves – either formally, informally, as individuals or together in groups. Where staff are learning, they are motivated and creative. When their PLD is planned, monitored and reviewed with them, they can share their successes and challenges with the teaching community, who in turn gain an insight and a further opportunity to develop their own practice.

You should aim for:

- regular dialogue about PLD with and between teachers

- accessible information about PLD opportunities

- teachers working to action plans for their own PLD

- monitoring and support of progress and outcomes of PLD activities

- records of PLD plans, activities and outcomes

Over time, a systematised PLD climate in your school will lead to improvements in learner outcomes.

6 Summary

In this unit you have looked at what constitutes teacher development, what this can involve and what can be learned within the school. Courses and training are not the only route to learning. A teaching career involves continuous learning; school leaders have a role to play in raising expectations for a continually developing staff group, and for facilitating opportunities to develop.

You have tried out some templates that may help you to implement PLD in your school and looked at some case studies to help you think about how to engage staff and keep records. But the exciting part comes next when you lead your staff to improve their practice to benefit the learning experience of students. Teachers who are committed to their own learning will naturally inspire students to feel the same way about theirs.

This unit is part of the set or family of units that relate to the key area of transforming teaching-learning process (aligned to the National College of School Leadership). You may find it useful to look next at other units in this set to build your knowledge and skills:

- Leading improvements in teaching and learning in the elementary school

- Leading improvements in teaching and learning in the secondary school

- Leading assessment in your school

- Supporting teachers to raise performance

- Mentoring and coaching

- Developing an effective learning culture in your school

- Promoting inclusion in your school

- Managing resources for effective student learning

- Leading the use of technology in your school.

Resources

Resource 1: Template for discussion with individual teachers

| Name of teacher | |

|---|---|

| Date | |

| What are you strengths as a teacher? What are you good at? | |

|

|

| What can you offer that we are not using in the school? Do you have any special interests or skills? | |

|

|

| What gets in the way of you being a better teacher? What could be done about that? | |

|

|

| Any other notes |

|

| Signature of school leader |

|

Resource 2: Storytelling, songs, role play and drama

Students learn best when they are actively engaged in the learning experience. Your students can deepen their understanding of a topic by interacting with others and sharing their ideas. Storytelling, songs, role play and drama are some of the methods that can be used across a range of curriculum areas, including maths and science.

Storytelling

Stories help us make sense of our lives. Many traditional stories have been passed down from generation to generation. They were told to us when we were young and explain some of the rules and values of the society that we were born into.

Stories are a very powerful medium in the classroom: they can:

- be entertaining, exciting and stimulating

- take us from everyday life into fantasy worlds

- be challenging

- stimulate thinking about new ideas

- help explore feelings

- help to think through problems in a context that is detached from reality and therefore less threatening.

When you tell stories, be sure to make eye contact with students. They will enjoy it if you use different voices for different characters and vary the volume and tone of your voice by whispering or shouting at appropriate times, for example. Practise the key events of the story so that you can tell it orally, without a book, in your own words. You can bring in props such as objects or clothes to bring the story to life in the classroom. When you introduce a story, be sure to explain its purpose and alert students to what they might learn. You may need to introduce key vocabulary or alert them to the concepts that underpin the story. You may also consider bringing a traditional storyteller into school, but remember to ensure that what is to be learnt is clear to both the storyteller and the students.

Storytelling can prompt a number of student activities beyond listening. Students can be asked to note down all the colours mentioned in the story, draw pictures, recall key events, generate dialogue or change the ending. They can be divided into groups and given pictures or props to retell the story from another perspective. By analysing a story, students can be asked to identify fact from fiction, debate scientific explanations for phenomena or solve mathematical problems.

Asking the students to devise their own stories is a very powerful tool. If you give them structure, content and language to work within, the students can tell their own stories, even about quite difficult ideas in maths and science. In effect they are playing with ideas, exploring meaning and making the abstract understandable through the metaphor of their stories.

Songs

The use of songs and music in the classroom may allow different students to contribute, succeed and excel. Singing together has a bonding effect and can help to make all students feel included because individual performance is not in focus. The rhyme and rhythm in songs makes them easy to remember and helps language and speech development.

You may not be a confident singer yourself, but you are sure to have good singers in the class that you can call on to help you. You can use movement and gestures to enliven the song and help to convey meaning. You can use songs you know and change the words to fit your purpose. Songs are also a useful way to memorise and retain information – even formulas and lists can be put into a song or poem format. Your students might be quite inventive at generating songs or chants for revision purposes.

Role play

Role play is when students have a role to play and, during a small scenario, they speak and act in that role, adopting the behaviours and motives of the character they are playing. No script is provided but it is important that students are given enough information by the teacher to be able to assume the role. The students enacting the roles should also be encouraged to express their thoughts and feelings spontaneously.

Role play has a number of advantages, because it:

- explores real-life situations to develop understandings of other people’s feelings

- promotes development of decision making skills

- actively engages students in learning and enables all students to make a contribution

- promotes a higher level of thinking.

Role play can help younger students develop confidence to speak in different social situations, for example, pretending to shop in a store, provide tourists with directions to a local monument or purchase a ticket. You can set up simple scenes with a few props and signs, such as ‘Café’, ‘Doctor’s Surgery’ or ‘Garage’. Ask your students, ‘Who works here?’, ‘What do they say?’ and ‘What do we ask them?’, and encourage them to interact in role these areas, observing their language use.

Role play can develop older students’ life skills. For example, in class, you may be exploring how to resolve conflict. Rather than use an actual incident from your school or your community, you can describe a similar but detached scenario that exposes the same issues. Assign students to roles or ask them to choose one for themselves. You may give them planning time or just ask them to role play immediately. The role play can be performed to the class, or students could work in small groups so that no group is being watched. Note that the purpose of this activity is the experience of role playing and what it exposes; you are not looking for polished performances or Bollywood actor awards.

It is also possible to use role play in science and maths. Students can model the behaviours of atoms, taking on characteristics of particles in their interactions with each other or changing their behaviours to show the impact of heat or light. In maths, students can role play angles and shapes to discover their qualities and combinations.

Drama

Using drama in the classroom is a good strategy to motivate most students. Drama develops skills and confidence, and can also be used to assess what your students understand about a topic. A drama about students’ understanding of how the brain works could use pretend telephones to show how messages go from the brain to the ears, eyes, nose, hands and mouth, and back again. Or a short, fun drama on the terrible consequences of forgetting how to subtract numbers could fix the correct methods in young students’ minds.

Drama often builds towards a performance to the rest of the class, the school or to the parents and the local community. This goal will give students something to work towards and motivate them. The whole class should be involved in the creative process of producing a drama. It is important that differences in confidence levels are considered. Not everyone has to be an actor; students can contribute in other ways (organising, costumes, props, stage hands) that may relate more closely to their talents and personality.

It is important to consider why you are using drama to help your students learn. Is it to develop language (e.g. asking and answering questions), subject knowledge (e.g. environmental impact of mining), or to build specific skills (e.g. team work)? Be careful not to let the learning purpose of drama be lost in the goal of the performance.

Resource 3: An introduction to action research in the classroom

Ben Goldacre (2013) argues that teaching should be an evidence-based profession and that this would lead to better outcomes for children. In particular, he suggests that a change in culture is needed, in which teachers and politicians recognise that we don’t necessarily ‘know’ what works best – we need evidence that something works.

The assumption is that the evidence-based practice is a good thing and that the changes advocated by Goldacre can be achieved through teachers researching their own practice. Indeed, where research practices are embedded in schools, there is a recognition that this can contribute to school improvement.

As a teacher undertaking a study in your own classroom, it is likely that it will be relatively small-scale and short-term and action research methodology works well in this context. Action research involves practitioners systematically investigating their own practice, with a view to improving it.

Action research involves the following steps:

- Identify a problem that you want to solve in your classroom: This might be something quite specific such as why certain pupils do not answer questions or find an aspect of your subject hard or de-motivating, or it might be something more general like how to organise group work effectively.

- Define the purpose and clarify what form the intervention might take: This will involve consulting the literature and finding out what is already known about this issue.

- Plan an intervention designed to tackle the issue.

- Collect empirical data and analyse it.

- Plan another intervention: This will be based on what you find and will be designed to further understand the issue that you have identified.

Action research is a cyclical process (Figure R3.1). Through repeated intervention and analysis, you will come to understand the issue or problem and hopefully to do something about it.

Figure R3.1 Action research cycle

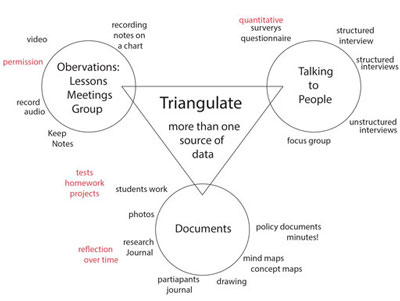

Having decided on the questions you would like to answer and the approach you wish take, you will need to collect some data that will enable you to answer the questions. There are three broad ways in which you can collect data, you can:

- observe people at work

- ask questions (either through survey’s or by talking to people)

- analyse documents.

Figure R3.2 provides an overview of different data collection methods.

You will need evidence from several sources of data in order to be confident in your findings. Each method will have advantages and limitations; you need to make sure that you act in such a way as to minimise the limitations.

You need to consider both the validity and reliability of the data that you collect. If something is valid then that suggests that it is true or trustworthy. It is useful to ask the following questions to test validity:

- Can the results be generalised? Someone who hears about or reads about your research might decide that, based on their experience then it is authentic and seems sensible.

- Does the data support the conclusions? This is more likely if there is more than one source of data collected over a period of time or if the findings have been checked with the participants.

- Do the questionnaire or interview questions relate clearly to the research questions?

Reliability is a difficult concept as it is to do with repeatability and replicability. Reliability includes fidelity to real life, authenticity and meaningfulness to the respondents. Cohen et al. (2003) suggest that the notion of reliability should be construed as ‘dependability’ and achieving dependability relies on factors such as collecting enough data, checking your findings with the participants, and looking for evidence of the same idea from more than one data source.

Resource 4: Template for action planning

| Name of teacher | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Date | |||

| Identified need or underused skill | How need will be met | Who involved | By when |

|

|||

| Any other notes |

|

||

| Signature of school leader |

|

||

Additional resources

- ‘10 professional development ideas for teachers’: http://www.theguardian.com/ teacher-network/ teacher-blog/ 2013/ oct/ 22/ teacher-professional-development-school-advice

- Learning to teach: an introduction to classroom research, an Open University OpenLearn unit: http://www.open.edu/ openlearn/ education/ learning-teach-introduction-classroom-research/ content-section-0

- ‘How principles can grow teacher excellence’ by Mariko Norobi: http://www.edutopia.org/ stw-school-turnaround-principal-teacher-development-tips

- ‘What is teacher development?’ by Linda Evans: http://www.education.leeds.ac.uk/ assets/ files/ staff/ papers/ What-is-teacher-Development.pdf

- ‘Theories on and concepts of professionalism of teachers and their consequences for the curriculum in teacher education’ by Marco Snoek: http://kennisbank.hva.nl/ document/ 477245

References

Acknowledgements

This content is made available under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike licence (http://creativecommons.org/ licenses/ by-sa/ 3.0/), unless identified otherwise. The licence excludes the use of the TESS-India, OU and UKAID logos, which may only be used unadapted within the TESS-India project.

Every effort has been made to contact copyright owners. If any have been inadvertently overlooked the publishers will be pleased to make the necessary arrangements at the first opportunity.

Video (including video stills): thanks are extended to the teacher educators, headteachers, teachers and students across India who worked with The Open University in the productions.