Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Friday, 27 February 2026, 11:02 PM

TI-AIE: Transforming teaching-learning process: mentoring and coaching

What this unit is about

Most of us have at some point in our lives benefited from the generosity of a friend or family member who has listened to us as we have struggled to come to terms with a challenge or a problem. In a professional context, such support and guidance is often referred to as coaching or mentoring, and in this unit you will learn to distinguish between these two approaches. You will understand some of the skills and techniques associated with coaching and mentoring, and how to use them in your conversations with teachers, students and their parents and/or guardians.

Increasing international evidence demonstrates that leaders can significantly improve the performance of their organisations and communities through coaching and mentoring (for example, Barnett and O’Mahony, 2006). In India, the National Programme Design and Curriculum Framework highlights how coaching and mentoring can enhance the effectiveness of classroom teaching and how as a school leader you can employ these techniques to improve teaching and learning in your school (National University of Educational Planning and Administration, 2014).

By applying such strategies, leaders can significantly improve the performance of the individual being coached or mentored, while contributing to the success of their organisation. School leaders rarely have control over the resources, but they do have the ability to create a school culture that values everyone in the school and emphasises the importance of relationships and provides support to teachers. Practising coaching and mentoring in your school and sharing the skills with colleagues will contribute to richer relationships between teachers and students, which will directly impact on the quality of learning and achievement.

Learning Diary

During your work on this unit you will be asked to make notes in your Learning Diary, a book or folder where you collect together your thoughts and plans in one place. Perhaps you have already started one.

You may be working through this unit alone, but you will learn much more if you are able to discuss your learning with another school leader. This could be a colleague with whom you already collaborate, or someone with whom you can build a new relationship. It could be done in an organised way or on a more informal basis. The notes you make in your Learning Diary will be useful for these kinds of meetings, while also mapping your longer-term learning and development.

What school leaders can learn in this unit

- To distinguish between mentoring and coaching, and how both can be used to support staff learning.

- To have conversations with members of staff that improve teaching and learning in your school.

- To plan and deliver coaching and mentoring sessions with agreed outcomes.

- To consider the benefits of a coaching culture in your school.

1 What coaching and mentoring have in common

Most people speak of coaching and mentoring as if they were the same thing. While they are two different approaches to working with individuals and teams, they do have one important thing in common: both depend for their effectiveness on being able to develop strong, trusting relationships with the person who the coach or mentor is helping. Learning how to hold consensual conversations is really important in forming such relationships.

A consensual conversation is one in which the two speakers are in harmony. While the purpose of their conversation may not be to seek agreement, they do agree about how they will:

- listen to and understand each other

- show true interest in what the other person is sharing

- show respect for the other person and for the views that they express.

As a school leader, you may be used to having people agree with you just because of who you are. Holding truly consensual conversations may therefore be a skill that you often have to learn and practise!

Figure 1 A conversation with a clear purpose.

It is important to remember that two colleagues casually talking with each other about their work is simply a ‘chat’. When their conversation is deliberately designed to help one of them address a problem or seize an opportunity, it has a clear purpose – ultimately, to improve teaching and learning – and moves into the territory of coaching or mentoring.

Activity 1: What sets coaching and mentoring apart?

Read the definitions of coaching and mentoring in Resource 1. Write down in your Learning Diary your own summary of the difference between the two terms, thinking about how you might explain the concepts to your staff.

List three ways in which coaching and/or mentoring could make a difference to staff performance and therefore student learning in your school. You might, for example, think about specific staff or about specific student needs or about a curriculum area that you are concerned about.

Discussion

It is important to distinguish the role of mentor and coach, as they operate in different ways and offer different types of support. When you differentiated between the two and thought about ways you might use these approaches in you school, you probably realised that it is important to pick the right approach and that they are both about an ongoing commitment to developing your staff, not about single conversations. What drives coaching and mentoring is the goal of improving teaching and learning, and conversations should focus on this.

- A mentor is usually an experienced specialist in their chosen field and, ideally, is also a wise person who has a wide range of experiences to draw upon. They bring to you their considerable experience and knowledge of the subject to be discussed.

- A coach helps you to come up with your own answers to issues that you are struggling with. Their most common tool is the question, and their most valued characteristic is the quality of their listening.

Did you think of ways that coaching or mentoring might help in your school? Maybe you have in mind a new teacher who would benefit from a weekly session of mentoring to guide them to put their training into practice in the classroom, advising on how to deal with issues and manage their class. You may have thought about the issue of low participation of female students in classes and thought how you could use coaching to encourage teachers to improve participation in learning. You might want to see an improvement in science teaching and ask a senior science teacher to mentor their colleagues to pass on their expertise.

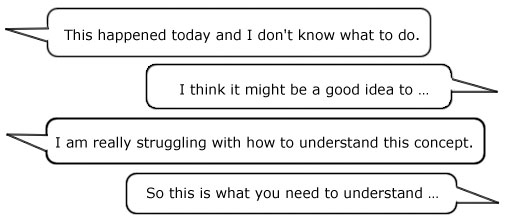

Most of us have benefited at some time from the support of a mentor in our personal or professional lives. In almost every family there is a wise ‘uncle’ or ‘aunty’ who is consulted before any life-changing decision is taken. As a school leader, you will certainly have to undertake this role, whether it is supporting a colleague through a crisis or helping them improve their classroom practice. Typically, the mentor will come up with answers to questions and solutions to problems. The best of them have the ability to ask really good questions that help their mentee come up with their own answers. However, the mentor has in mind what the answer might be. Over time they act as guides on a road that they have already travelled. A mentoring conversation might go like this:

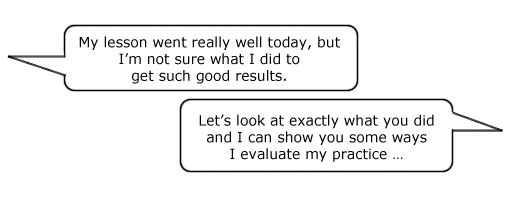

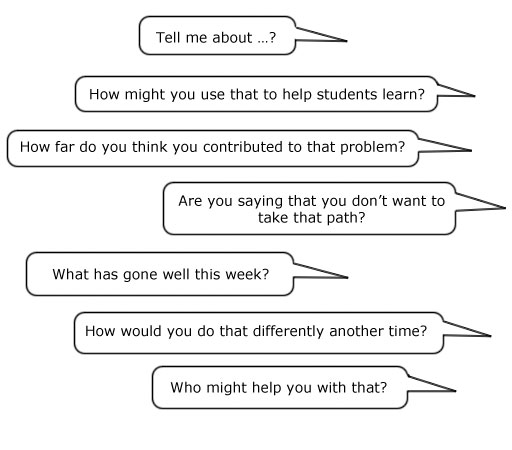

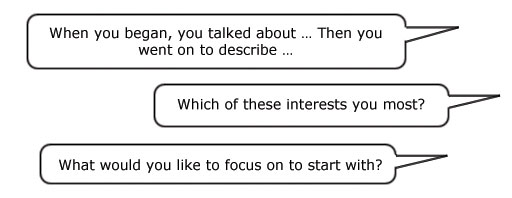

The job of a coach is to draw out the thoughts, ideas and concerns of the coachee (the person that they are coaching). They do this first to help them decide what exactly they want to talk about and can then replay what is said in order to help the coachee ‘hear’ their own thoughts and ideas. The coach’s persistent refusal to contribute their own ideas is essential for the coachee to come up with their own solutions. The most common habit is to sit still and say nothing; this may be the biggest challenge of all for you in learning to coach. A coach’s questions might be:

It is important to remember that coaching and mentoring conversations should celebrate the skills and successes, not just any deficits. Teachers need to recognise what they do well in order to repeat and develop it, and coaching and mentoring should identify strengths as well as weaknesses.

At times, mentoring and coaching conversations may touch on personal issues. It is important to remember, however, that your purpose is to help the individual solve a professional problem with a view to improving their performance and student learning.

Activity 2: Who do I need to listen to?

In this activity you should think about the sorts of challenges that you and your colleagues face in school that would benefit from a mentoring or coaching conversation. Work on the first part of the activity alone. You might wish to encourage others to offer their ideas for the second part.

Reflect on the following prompts and jot down your thoughts in your Learning Diary:

- Focus on two teachers in your school. One should be less experienced who you might mentor so that they can benefit from your knowledge and skills. The other teacher might be someone who you think could benefit from rethinking their approach or finding solutions to some of the problems that they are encountering.

- Identify the sort of issues or incidents that have arisen for them in the last week that have impacted on their teaching. This could be very varied, such as non-attendance due to the harvest, low confidence in teaching an unfamiliar subject, late students regularly disrupting the lesson or having to teach two classes due to shortage of teachers.

Now you have identified a ‘who’ and ‘about what’, copy Table 1 below into your Learning Diary and fill in the first two columns.

| Colleague role | Issue, incident or opportunity | Type of conversation: coaching or mentoring | Venue | Commentary |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||

|

||||

|

Now decide if the approach you should take is mentoring or coaching, and write this in the next column against each colleague you have identified. Think about whether you are helping people find their own solutions through questioning and listening (coaching) or whether you are taking more of an expert role and guiding them as to what to do using your expertise (mentoring). You may find that you also use coaching with the inexperienced teacher (for example, to help them to generate ideas for engaging with parents) and on some issues – such as taking responsibility for the maths curriculum across the school – you decide to mentor the other teacher over a period of time. The two approaches are not exclusive.

Use the fourth column to think about where you will have this conversation; the venue. Mentoring someone on developing their teaching resources and displays would probably take place in a classroom, while coaching someone to improve their marking of student work will need to be somewhere where neither of you will be disturbed. Remember that conversations can take place in a classroom or a quiet corner of the school grounds. Your office, if you have one, is probably the worst place to try to talk to someone, because of the power issues associated with that environment. The subject of the conversation will often determine the venue.

Lastly, make some notes in the final column to remind you of any issues and to guide your conversation.

Discussion

Now look at Table 2, which shows an example of a matrix filled out by a school leader when they were planning two conversations in their week. How does it compare to yours?

Table 2 Colleague coaching and mentoring matrix – filled-in example.

| Colleague role | Issue, incident or opportunity | Type of conversation: coaching or mentoring | Venue | Commentary |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Teacher | Family illness | Mentoring | Anywhere where they can have a cup of tea and not feel uncomfortable | You will want to be as supportive as possible to the member of staff but you are primarily concerned with minimising the impact on student learning. |

| Subject head | How to deal with an under-performing member of staff in their department | Coaching/mentoring | In their office or classroom, as long as you will not be disturbed | Although it may be necessary to provide some guidance, the aim is to help the head of department to come up with the solution to a problem they have been avoiding all year. This conversation is not about the under-performance as such; it is about developing the skills and confidence in the subject head to tackle the issue. |

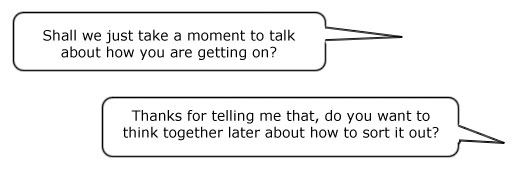

It is helpful to think ahead to make your conversations most effective. This way you can ensure that you broach difficulties with tact but directness, as you will have thought ahead about what to say and where to say it. Often the opportunity to have these conversations presents itself as part of a daily routine, and this is another reason to be ready to talk with your colleagues naturally and in a spontaneous fashion – for example:

2 Preparing for a conversation with a purpose

Good coaches and mentors share many values and practices, and are committed to offer support over a period of time where one conversation leads to another. In this way the relationship of trust can develop; but note also that the influences on teaching and learning arising from mentoring and coaching will only happen over time. The mentor or coach makes sure that the place, time and mood are right for each conversation. Sometimes this will mean a regular weekly session in the same venue; at other times, it will be a more casual encounter. While sometimes the session can be for just a few minutes in a corridor, usually it will take at least half an hour.

The coachee or mentee needs to know that the conversation is focused entirely on them. As a coach or mentor you should ideally choose a time and place to suit them, and where you will not be disturbed.

Figure 2 It is important to consider where you hold a conversation.

There are some really important dos and don’ts regarding the setting of the conversation:

- Turn all mobile phones onto silent and put them away.

- If you are sitting, arrange the seats at an angle to each other and far enough apart so that the mentee or coachee doesn’t feel intimidated. This is especially important if the conversation is between a man and a woman. It is better not to sit behind your desk.

- If you, as the coach, need to take notes, you should ask if it's acceptable. (You should also check whether the coachee wants to take notes as well.)

- Maintaining eye contact is really important, as is nodding to show that you are listening.

- Agree at the start how much time you will spend together.

And now it is time to have the conversation. Firstly you will look at the role of coach and then at the role of mentor.

Preparing for a conversation as a coach

From the moment you start the session, your only focus should be the person with you.

Your first job is to make your coachee feel at ease. After you ask them what they want to talk about, just listen. When they pause, ask them to tell you more.

Stay as still as possible. Anything that distracts the speaker will stop the flow of their thoughts. Watch how they sit and how they hold themselves. Try to mirror their shape in how you sit without being artificial; you might lean forward when they do, or gesture with your hands. Often this mirroring happens very naturally in a flowing conversation.

If your coaching is on a specific topic that you agreed beforehand (see Resource 2 for an example of using coaching to explore CCE), then you still need to listen to what the coachee understands in the first instance.

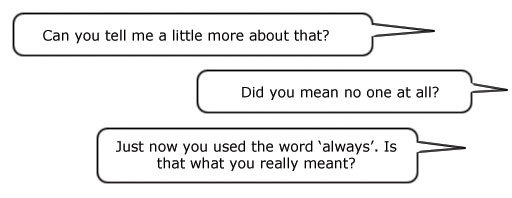

Coaching can be very tiring, because you have to listen so hard. You need to provide feedback to the speaker on what they are saying, so you sometimes have to work very hard at remembering. Do not be worried about taking notes of a few key words or phrases that you have heard. Coaches normally ask permission, in the form of ‘Would you mind if I took a few notes?’ When you give feedback, as you should regularly, use phrases such as:

This early stage can take quite a while, because the first idea that the coachee talks about may very often not be what is uppermost in their mind. Do not be hasty and push them too soon. Allow the conversation to take its natural course.

Once you are confident that your coachee is clear about what they really want to talk about, you are probably ready to establish with them what they want the outcome of the conversation to be. This might take the form of the following statement, said by you as the coach:

To do this you will need to explore with them what a successful outcome would look like.

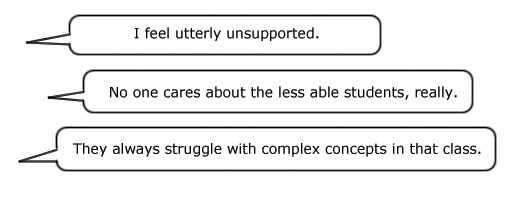

Throughout the session, watch how the coachee’s expression changes and how their hands move. These are important clues to their feelings. But most importantly, listen really closely to the words that your coachee uses, for example:

Your response to statements such as these could include:

Coaches call this form of enquiry activity ‘breaking the code’.

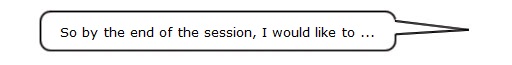

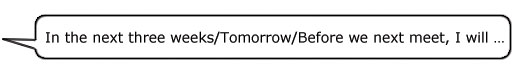

Your final task as the coach is to agree the actions from the session and what the coachee is committing to. Get them to write down the actions they intend to take and agree a timescale that they will be completed in. Your session should always end with the coachee making a commitment such as:

By summarising their thoughts and clarifying any remaining uncertainties, your coachee will be much more likely to choose a next step that they are comfortable with adopting and realistic enough to be doable. Finally, repeat to them what they have committed to and, if appropriate, agree the date for your next coaching session.

Preparing for a conversation as a mentor

Putting your mentee at ease is just as important for the mentor as it is for the coach with the coachee. Because you are taking on the role of a more knowledgeable professional, offering your experience and expertise, it is possible that your mentee could be really intimidated by you if you don't start things off well. It is therefore even more important for you to remember that if you remain seated behind your desk, your wisdom will not leave the room with the person who needs it most. The kindness in your eyes, the way in which you draw the mentee into the room, how you settle them comfortably and sit with them – all these things will make starting the conversation much easier.

As before, it is courteous to ask for permission to take any notes and make it clear that the mentee can make notes too, if they wish.

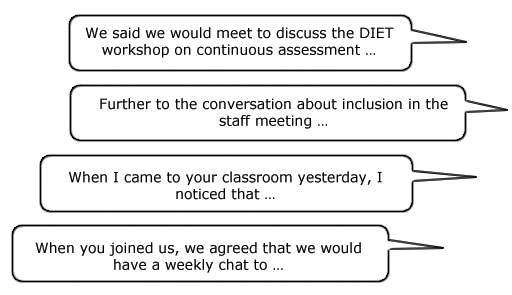

It doesn't matter how you introduce the conversation, but it is likely that it will be as a consequence of a previous interaction:

As before, the mentee should establish what they want to do. To help them with this, it is often useful to summarise what you have heard, what your contribution has been and what areas you have covered together. You should then agree the outcome of the session and what your mentee is committing to.

Activity 3: How does a mentoring conversation differ from a coaching one?

Bearing in mind the differences in the definitions of coaching and mentoring that you read above, write down in your Learning Diary the sort of things that a mentor might say in response to the statements you have already seen:

As you help your mentee to work out how to take their next step, your aim is to help them to reach a successful outcome. You may well take a more active role and begin to bring your experience and expertise into the conversation after you have listened to their concerns and thoughts. It is very important to remind yourself of a simple rule, however. If the idea is yours rather than theirs, then they won't own it. And if they don't own it, they won't succeed in making it happen. As a mentor you should not provide the solution, but be the conduit for the discovery, enabling others to decide on their actions.

Discussion

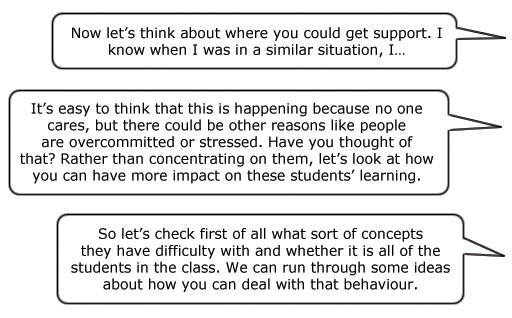

You might have come up with mentoring responses like these:

3 Coaching skills benefit all

Coaching skills are not exclusive to the school leadership role. A good coach can use their skills in other contexts and situations to help in their school community. The teacher who coaches can build self-reliance and confidence in students. Case Study 1 is an example of how coaching can even happen upwards between trusted colleagues. If you lead a coaching culture in your school, you can all benefit from the supportive atmosphere.

Case Study 1: Mr Kapur keeps a record of his school-based PLD

Mr Rawool, a school leader, is riding home on the bus with his deputy, Mrs Kapur, as they usually do. They often discuss work and this can be a time when they help each other out with questions and observations that help to define the problem and start exploring solutions.

| Mr Rawool | You know I told you about the TESS-India leadership units? Well, I’ve been studying one. It’s interesting, and the message is clear – I should be spending more time walking around the school and visiting the classrooms. I recognise the value of this, but it’s almost impossible with the size of my in-tray and the district education officer breathing down my neck. But where can I find the time to walk around the school and help teachers? I’m an administrator. I already take my own Class X mathematics class. |

| Mrs Kapur | I know that! You’re never late for the lesson, you are almost always smiling on your way to the classroom and you enjoy teaching your students almost as much as they enjoy being taught by you. Think about the impact you could have on the students if you were to spend time in the classes of other teachers. |

| Mr Rawool | Yes, but … |

| Mrs Kapur | But sir, don’t you remember talking to me about your own principal, his relationship with the boys and how he was always dropping into your classroom? |

| Mr Rawool | Times have changed. He didn’t have half my paperwork! But I’ve been thinking that I would love to spend more time in other teachers’ classrooms. I know I didn’t tell you, but when you were attending the training organised at the block level last week, I went out to find Mr Banerjee. I didn’t see him in his classroom, even though the students were there. I eventually tracked him down reading the newspaper in the staff room and sent him back to his class. That got me thinking about what it is like for our students. So I spent the next hour going in and out of classrooms. While Mrs Nagaraju was obviously pleased to see me and welcomed me into her classroom, most of the others wondered why I wasn’t in my office! I am sure if I did this regularly it would make the school better for the students. But how am I to manage it? Administration, teacher support, talking to students and visiting the classrooms!? |

| Mrs Kapur | Why don’t we talk about that on Monday? Let’s just enjoy our weekend with our families. You know I will help you! |

Activity 5: Initiating your first mentoring or coaching conversations

Following up on your initial thoughts about two of your teachers in Activity 2, you are now going to make plans to meet with them to provide some mentoring and/or coaching support.

- Find an opportunity to talk to the teachers and offer your help. Think about how you are going to explain your offer so that it does not worry them – remember, the idea of coaching and mentoring might be new to them. Look back at the summaries you made in your Learning Diary. Agree a time and place to meet.

- Now take a deep breath – it is time to be a coach or mentor. Before you begin, refresh your memory of the various tips and ideas in this unit. Perhaps write yourself some short notes to have with you in the session and maybe some of the questions you might ask.

- Record your reflections in your Learning Diary as soon as possible after you have finished the sessions. There are two key questions:

- In what ways did you either assist or hinder the coachee/mentee to find their way towards a resolution to their issue?

- What would you change next time?

- Think about how you might gather the feelings of your coachee/mentee about the usefulness of the session. Their feedback will help you improve.

Discussion

It is probably easier to think of all the things you did wrong or could have done better, but do try to spend a few minutes thinking about the things you did right.

What did the coachee/mentee think? Over time you might like to ask them what was helpful and what was not helpful – this way you can adjust your style and interventions based on their feedback rather than your own impressions.

If it is the first time you have tried coaching or mentoring, the atmosphere may well have been awkward and strained. Don’t be put off. The power relationships involved are always likely to make it difficult on the first few occasions, particularly with someone who is not part of the teaching staff.

If your coachee/mentee does not avoid you over the next few days, you can be assured they have not been harmed by your conversation! If they smile at you or share their progress ahead of the next meeting, you should be very pleased.

Benefits of developing a coaching culture in your school

As a school leader, you may become adept at coaching and mentoring yourself. But by creating the space and dialogue more widely in the school, you can encourage teachers to become more reflective, more articulate about their practice and more experimental in their teaching. Such dialogue will have a positive impact on student learning as teachers will become more conscious of their teaching activities and more confident to use a wider pedagogic range of techniques. You will find (in Lofthouse et al., 2010) that coaching and mentoring will impact on planning, monitoring and improving teaching quality as teachers:

- experience and develop understanding of an integration of knowledge and skills

- gain multiple opportunities to learn and apply information

- find their beliefs challenged by evidence that is not consistent with their assumptions

- have opportunities to process new learning with others.

You may want to institute training for teachers in coaching and mentoring, and offer a dedicated time each day or week for the activity to take place. This coaching may focus on specific aspects of teaching and learning such as:

- working towards a school development priority

- supporting the teaching and learning of a specific group of students

- enabling the development of a specific teaching skill

- sharing classroom practice with a colleague.

Your own mentoring or coaching needs

You will have noted the benefits of having a mentor or coach and it is important that you as a leader can turn to other leaders to reflect on your practice, build on your strengths and address your development needs. You may already have colleagues who you speak to and share your thoughts and problems with, and with whom you generate solutions. It may be worth formalising such arrangements or seeking out others who might support you – leaders from other schools, or officers from the DIET or SCERT, for example.

4 Summary

This unit emphasises the importance of purposeful conversations with members of the school community in order to provide support and generate solutions. There are many opportunities to talk with your staff formally and informally, and this unit has discussed some of the factors that will make these conversations feel more collaborative and safe, especially important if a school community is unfamiliar with such dialogues.

Mentoring or coaching skills open up many possibilities for you as a school leader to optimise the potential of your teachers and help transform them into the excellent teachers and leaders that you want for your school.

The unit has also highlighted how helpful it can be to have a coach or mentor yourself, and you may want to consider how you could organise this.

This unit is part of the set or family of units that relate to the key area of transforming teaching-learning process (aligned to the National College of School Leadership). You may find it useful to look next at other units in this set to build your knowledge and skills:

- Leading improvements in teaching and learning in the elementary school

- Leading improvements in teaching and learning in the secondary school

- Leading assessment in your school

- Supporting teachers to raise performance

- Leading teachers’ professional development

- Developing an effective learning culture in your school

- Promoting inclusion in your school

- Managing resources for effective student learning

- Leading the use of technology in your school.

Resources

Resource 1: Some definitions of coaching and mentoring

The coach

- ‘The art of facilitating the performance, learning and development of another.’ (Downey, 2003)

- ‘We believe that coaching is primarily about performance … The core concept of our approach is that the individual or team being coached already has the resources within them to move forward and that the coach’s primary role is to help them access these resources.’ (The School of Coaching, undated)

- ‘Coaching is about performing at your best through the individual and private assistance of someone who will guide you to keep growing.’ (Gerard O’Donovan)

- ‘Unlocking a person’s potential to maximise their own performance. It is helping them to learn rather than teaching them.’ (Whitmore, 2003)

- ‘Coaching is about developing a person’s skills and knowledge so that their job performance improves, hopefully leading to the achievement of organisational objectives. It targets high performance and improvement at work, although it may also have an impact on an individual’s private life. It usually lasts for a short period and focuses on specific skills and goals.’ (CIPD, 2009)

- ‘A professional partnership between a qualified coach and an individual or team that support the achievement of extra-ordinary results, based on goals set by the individual or team.’ (ICF, undated)

- ‘Coaching is directly concerned with the immediate improvement of performance and development of skills by a form of tutoring or instruction.’ (Parsloe, 1995)

- ‘Facilitating the unleashing of people’s potential to reach meaningful, measurable goals.’ (Rosinski, 2003)

The mentor

- ‘MENTOR: 1. capitalised: a friend of Odysseus entrusted with the education of Odysseus’ son Telemachus. 2. (a) a trusted counsellor or guide; (b) tutor, coach.’ (Merriam-Webster definition)

- ‘Mentoring is a developmental relationship between a more experienced individual, a mentor, and a less experienced partner, a mentee. Through regular interactions, the mentee relies on the mentor’s guidance to gain skills, perspective, and experience.’ (Menttium, undated)

- ‘Mentoring is a developmental partnership through which one person shares knowledge, skills, information and perspective to foster the personal and professional growth of someone else. We all have a need for insight that is outside of our normal life and educational experience. The power of mentoring is that it creates a one-of-a-kind opportunity for collaboration, goal achievement and problem solving.’ (USC CMIS, undated)

- ‘Mentoring is a brain to pick, an ear to listen, and a push in the right direction.’ (John C. Crosby)

- ‘Mentoring is a term generally used to describe a relationship between a less experienced individual, called a mentee or protégé, and a more experienced individual known as a mentor. Traditionally, mentoring is viewed as a dyadic, face-to-face, long-term relationship between a supervisory adult and a novice student that fosters the mentee’s professional, academic, or personal development.’ (Donaldson et al., 2000)

- ‘The greatest good you can do for another is not just to share your riches but to reveal to him his own.’ (Benjamin Disraeli)

- ‘A mentor typically performs multiple roles, beyond that of an advisor. A mentor makes a special and often personal investment in the career development of a protégé. Often, a mentor is also:

- ‘A teacher – helping the protégé develop critical skills and hone unique talents.

- ‘A role model – providing an example and modeling best practices.

- ‘A friend – providing crucial psychosocial support and encouragement.’ (Arizona State University, undated)

Resource 2: An example of how coaching could be used in implementation of CCE

Possible themes for discussion during coaching for CCE

During the coaching cycle you may find the following themes for discussion useful. It is likely that one or more of these will be dovetailed with the coachee’s focus for development. The list is not exhaustive.

- What are we looking for in terms of positive student response?

- What are the planning implications of CCE?

- How can we make practical strategies for CCE work to their full potential?

- What does progression look like in relation to CCE for both the teacher and the pupils?

- What specifically needs to be really understood about the subject in this context and how does CCE help?

What kind of evidence might be useful?

It is important to balance out a focus on teaching with the necessary focus on learning. As such, the coach and coachee will particularly want to consider the lessons from the pupils’ perspective. It is not always easy to do this, and we all too often play the long game and wait for evidence of student outcomes from formal assessment opportunities. This may not always be helpful in coaching.

Alternative sources of evidence may include talking to pupils and looking in detail at their work to investigate the following questions:

- What has been understood by pupils and how does it relate to the learning objectives?

- What were the students’ experiences during the CCE process and were these uniform or varied?

- What classroom dialogue (in groups or between teacher and pupils) supported the CCE process? How can this dialogue be characterised?

- How are students making sense of the information they are given and the language used in relation to CCE?

With time it may be useful to use the coaching process to add further information to the guide. For example this might include:

- assessment for learning principles

- common misconceptions related to CCE

- good practical strategies

- common problems/barriers in developing practice

- useful resources and how to access them.

(Note that ‘CCE’ stands for ‘continuous and comprehensive evaluation’. Adapted from Lofthouse et al., 2010)

References

Acknowledgements

This content is made available under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike licence (http://creativecommons.org/ licenses/ by-sa/ 3.0/), unless identified otherwise. The licence excludes the use of the TESS-India, OU and UKAID logos, which may only be used unadapted within the TESS-India project.

Every effort has been made to contact copyright owners. If any have been inadvertently overlooked the publishers will be pleased to make the necessary arrangements at the first opportunity.

Video (including video stills): thanks are extended to the teacher educators, headteachers, teachers and students across India who worked with The Open University in the productions.