Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Friday, 27 February 2026, 9:22 PM

TI-AIE: Perspective on leadership: building a shared vision for your school

What this unit is about

This unit is about developing and implementing a vision for your school. Sunil Batra (2011) reflects that in India, ‘schools rarely visualise or articulate their own vision’.

This view is probably based on the fact that in the past, schools have been controlled by the District Education Office. A clear aspiration of the Right to Education Act (RtE) 2009 is that schools should become more autonomous, taking responsibility for their own continuous improvement and being responsive to the local community. The establishment of school management committees (SMCs) and the requirement that all schools should have a ‘school development plan’ (SDP) in place are intended to support this aspiration.

Batra goes on to suggest that ‘not having a vision, a goal or an aim to work for with a moral purpose of development for a people or a community is tantamount to working in a void’.

The power of vision is seen in this story: a stonemason was shaping a keystone to place at the apex of a doorway to a temple and was asked by a visitor, ‘What are you doing?’ The reply was immediate and unexpected: ‘I am helping to build a temple to the glory of God.’ The stonemason did not describe his actions, the choice of stone, his skills or any issues – instead he described the purpose, and the passion that drove him and his community to realise their vision for a splendid temple. The vision gave him the energy, pride and commitment to engage as a team member in creating something of quality. The challenge of striving for something that may always be just out of reach is what leads communities to achieve far more than would otherwise be the case.

As a school leader, it is your responsibility to create a vision for your school. That vision needs to be shaped to fit the school’s particular context, as well as the needs and aspirations of both the school and the wider community. Its design should reflect the school’s cultural identity and the attributes of its students and their families.

In this unit you will consider what makes a good vision statement, how to involve stakeholders in the creation and realisation of the vision and how the vision translates into action.

Learning Diary

During your work on this unit you will be asked to make notes in your Learning Diary, a book or folder where you collect together your thoughts and plans in one place. Perhaps you have already started one.

You may be working through this unit alone, but you will learn much more if you are able to discuss your learning with another school leader. This could be a colleague with whom you already collaborate, or someone with whom you can build a new relationship. It could be done in an organised way or on a more informal basis. The notes you make in your Learning Diary will be useful for these kinds of meetings, while also mapping your longer-term learning and development.

What school leaders will learn in this unit

- How a school vision informs everyday actions to improve a school.

- How to formulate your own school vision.

- How to involve others in developing and implementing a vision that makes a difference to students.

1 The importance of having a clear vision for your school

The purpose of these School Leadership units is to help you to become a more effective leader in your school. Four behaviours that characterise an effective school leader (Rutherford, 1985) are to:

- have clear, informed visions of what they want their schools to become; visions that focus on students and their needs

- translate these visions into goals for their schools and expectations for their teachers, students and administrators

- not stand back and wait for things to happen, but continuously monitor progress

- intervene, when necessary,in a supportive or corrective manner.

So developing a vision for your school is an important part of being an effective school leader. In a report that examined a number of educational systems across the world to see what factors led to improvement, it was found that ‘almost all school leaders say that setting vision and direction’ are among ‘the biggest contributors to their success’ (McKinsey & Co., 2010).

A ‘vision’ is a clear statement of what the school is trying to achieve so that all stakeholders – teachers, students, their families and community members – are working together. It is about looking forward and seeking to motivate and unify everyone to achieve the very best for the students. The vision needs to capture the aims of a school in its particular context, and guide and inform the preparation of a school development plan.

A vision is important for schools (West-Burnham, 2010) because it:

- provides the focus for all aspects of organisational life

- informs planning and the development of policies

- clarifies and prioritises the work of individuals

- helps to articulate shared beliefs and develop a common language,thereby securing alignment and effective communication

- characterises the organisation to the rest of the world.

The vision is much more than a few words of vague intention; it embodies the values of the community and is the foundation for actions that will lead to school improvement.

Pause for thought

|

2 What is a vision statement?

A vision statement is essentially a value statement. It summaries the moral purpose of the school and reflects a set of shared values. A good starting point in the process of establishing a vision for your school is to examine your own values and beliefs and the values embodied in the NCF 2005 and the RtE 2009.

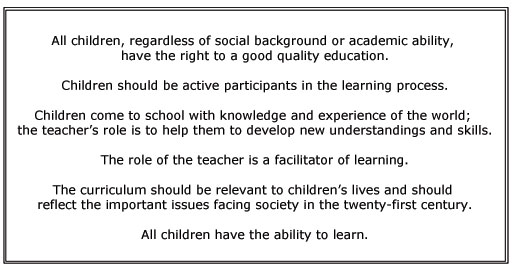

The NCF 2005 sets out an ambitious programme for education in India and the RtE 2009 puts into place some of the structures that will support the implementation of the NCF 2005. The RtE 2009 also stresses the responsibility of a school to address the needs of all students and foster inclusion. Both are underpinned by a particular set of values (Figure 1).

Figure 1 The values underpinning the NFC 2005 and the RtE 2009.

The values in Figure 1 challenge some historically held beliefs. For example, in some schools:

- students from different castes are seated separately and given fewer opportunities to take part in the lessons

- male students are sometimes favoured over female students as their education is considered to be more important

- some teachers believe that students with rural backgrounds do not have the ability to learn

- teachers are often considered to be the experts providing knowledge and wisdom that students are expected to absorb.

As a school leader in India in the twenty-first century, your role is to translate the aspirations of the NCF 2005 and RtE 2009 into practice in your school. Establishing a shared vision that embodies the values set out in Figure 1 is the starting point.

In Activity 1 you will have opportunity to reflect on the values embodied in some vision statements and to reflect on the sort of behaviours that you can adopt that are consistent with the values that underpin the NCF 2005 and the RtE 2009, and therefore the vision for your school.

Activity 1: Thinking about values

If possible, you should do this activity with another school leader, or with your deputy.

Look at the vision statements in Table 1. Analyse each statement in terms of the underlying values that are implied. Which ones are consistent with the values that underpin the NCF 2005 and the RtE 2009?

| School and statement | What is valued? | Is this consistent with the NCF 2005 and RtE 2009? |

|---|---|---|

| Lahsuniya School: ‘Families and school work together to support children’s learning’ | ||

| Neelam School: ‘Every child in this school is encouraged to develop their full potential in a stimulating and caring environment’ | ||

| Panna School: ‘To ensure 100% success in end-of-school examinations’ | ||

| Moonga School: ‘Our vision is to provide a happy, caring and stimulating environment where children learn to make their best contribution to society’ | ||

| Mukta School: ‘To meet the needs of all its pupils’ | ||

| Manik School: ‘Our school is a place of excellence where children can achieve their full potential’ | ||

| Gomedha School: ‘To be the best school in the district’ | ||

| Pukhraj School: ‘To ensure that all students have the chance to go to university’ | ||

| Aakash School: ‘Every teacher strives for the best for every single child’ | ||

| Heera School: ‘We believe that every child is entitled to enjoy his/her childhood. They should be valued for their individuality, culture and heritage’ | ||

If members of your school community have historically held values and beliefs that are inconsistent with the NCF 2005 and REA 2009, you will not be able to change their views overnight. However, by adopting certain behaviours yourself and expecting your teachers to do the same, you will be able to create an environment where the values set out in Figure 1 will become established.

For each of the statements in Figure 1, identify some behaviours that you could adopt which will reinforce these values.

Discussion

Some of the statements in Table 1 fit the NCF 2005 and RtE 2009 statements very well, but some do not. For example, the desire for all students to go to university might appear to be aspirational, but is it realistic? The message is that going to university is more important than anything else; whereas in practice, it is not an appropriate ambition for some students. The statement from Heera School is certainly inclusive, but is it aspirational? The statements that seem to fit the criteria best are perhaps those from Neelam and Moonga Schools, as they emphasise wellbeing and the desire that all students achieve their full potential.

You can model inclusion values through talking to students and about students. The key resource ‘Involving all’ could be used to support your teachers in modelling inclusive behaviours.

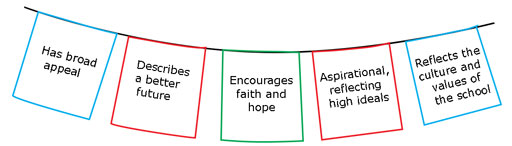

Figure 2 Features of a good vision statement.

3 Developing a vision for your school

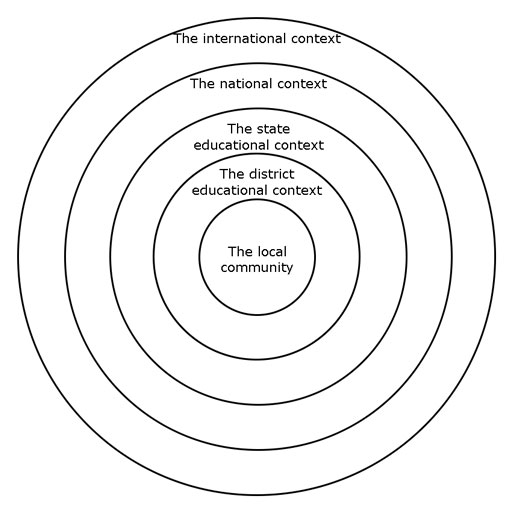

A school vision must reflect the unique context of each school. But it cannot exist in isolation; it must also reflect the wider factors and influences shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3 The wider contexts that must influence your vision.

National and state contexts are set by the NCF 2005 and the RtE 2009. Your task is to develop a vision for your school that enables you to fulfil these expectations within your individual context.

Case Study 1: Mrs Chadha decides on a school vision

Mrs Chadha was the principal of a large girls’ school. She went on a course where she realised the need for a school vison. During the course she was made aware of different visions, talked to a number of school leaders about their visions and was impressed by many of the ideas. She participated in discussions and became clear about the vision for her school.

She returned with enthusiasm and could not wait to tell the staff, parents and community about the new direction for her school. She realised that her school was doing a good job for its more able students, but it was not including all students equally and that many students who came with limited literacy skills were unhappy in school and not doing well. She thought that the vision should be: ‘A school in which every child succeeds’.

She called a number of meetings and shared her vision. There was little discussion and little changed after the meetings, although some parents and staff privately spoke about the danger of the school results going down as the teachers wasted time on the students who would never succeed. The vision did not seem to be making the difference in school and after a few weeks, Mrs Chadha realised that it had not been adopted by the teachers, parents or students, and had indeed created some tensions.

Activity 2: What might Mrs Chadha have done differently?

Note down your responses to these questions in your Learning Diary:

- What is your response to Mrs Chadha’s vision statement?

- What did she do right?

- Why do you think nothing changed?

- What might she have done differently?

Discussion

Mrs Chadha’s statement is consistent with the values of the NCF 2005. She was right to have meetings with a range of different people, but the lack of discussion meant that parents and teachers did not have ownership of the vision. A vision on its own is not enough. The vision needs to be shared and converted into actions.

Case Study 2: Mr Singh creates a vision for his school

Mr Singh attended a leadership development programme. He spent almost a whole day exploring the role of the school leader in creating a vision for his school. He talked to other school leaders about their visions for their schools. It was only when he walked into his own school that the message of that day really struck home.

Usually, Mr Singh would have gone straight to his office to fulfil his administrative duties. On that day he did little more than drop off his bag and check for urgent messages before beginning to walk around the school. He had often been in classrooms, but usually to talk with a teacher or discipline a student. Today, he was walking with a purpose, to answer the questions: ‘What sort of school have I been leading for the past 11 months and how effective are we in developing our students’ learning?’ During much of that day and for the rest of the week he hardly went to his office. During break times he sat with and talked to students. At the end of the day he stood by the school gate, talking to parents.

On the day after his return, he called his staff together. He did not talk explicitly about the school’s need for a vision. Instead, he told them that he was now convinced that if the school was to improve, the first step was for everyone to understand what needed to be done, based on the school’s strengths and weaknesses, and especially the school’s core purpose of teaching for learning.

The impact of his presence was almost instantly visible wherever he went. But it was his constant questions – ‘What are you proud of and what could we do better?’ – that were like a key turning in the lock of a door that had never before been opened.

The chair of the SMC came into the school to ask about his training programme. After an hour, he invited Mr Singh to his village to talk with some of the local community to get their sense of how they felt about the school and what they wanted from it.

At the end of that week, Mr Singh felt that he had learned more about his school from his observations and discussions than he had found out in the previous 11 months.

4 Involving stakeholders in building a vision for your school

In most cases, the development of the school vison will be led by the school leader. This is not always the case: a new school leader may come to a school and find that the community has a clear vision for the school, based on their understanding of the school and community over time. It is important that the vision unites stakeholders around the school’s journey of improvement. A school where community members and the school leader (the paid professional) are in disagreement will be an unhappy place where much energy is wasted rather than focusing on the key purpose of improving learning for the students.

All local communities are different. The key stakeholders around the school and its community will include:

- the teachers

- the students

- the parents and families of the students

- community leaders, including local businesses.

If stakeholders are to support the school’s development, they need to be involved in understanding and developing the school’s vision. Among the stakeholders will be people with varying degrees of education and understanding of what is required of modern schools. It is the responsibility of the school leader to inform and support their development. This may be challenging, especially if the vision involves improvement that is different from what has been historically provided. In one context, it may be right for the school leader to be quite directive and this may be appreciated by the school community; in a different context, such an approach may be resented and lead to problems.

Case Study 3: Mr Singh continues his work

Mr Singh continued to engage teachers, the SMC and community leaders in conversations about the school. He instinctively began by telling them about some of the things he had found that made him proud, and only then did he identify something that he was certain everyone knew needed to improve. He encouraged a similar approach from everyone. This was an important first step in the visioning process.

Mr Singh also continued to spend time walking around school and talking to students and staff, and to parents when they came to school. This information was valuable and he added this to the information he had already gathered. Here are some of his observations:

- Some teaching is strong. There are two very talented female teachers who are respected by staff and students.

- There are other teachers whose practice is poor, some of whom also are frequently absent.

- Enrolment and attendance of female students in the local middle school is very high. In the upper secondary school the enrolment figure drops to only 25% of the school roll.

- Female students are consistently the highest performing in state examinations.

- The toilets are poorly maintained and unhygienic. There is only one toilet for female students and this is located in the male students’ block.

- Some of the new teachers who joined this year are popular, but struggle with teaching and behaviour.

- Parents and the local community are very supportive.

Mr Singh was struck by what the school lost through the drop-out of female students before upper secondary, and the impact this had on the life chances of girls and young women from the local community. It had been the stench from the toilets that had finally got him thinking about the plight of the female students, something parents and the local community representatives had mentioned. His regular visits to lessons alerted him to the potential of role models for students and staff being demonstrated by the stronger female teachers.

He was convinced that the school’s vision needed to be about inclusion for all students, giving them access to the school and to high-quality teaching.

A few weeks after the training course, Mr Singh held a joint meeting of the staff (six teachers) and the SMC (four parents, two community leaders and local businessman). By this time everyone had heard about his course and had seen him around the school, talking about what they did well and what needed changing. Mr Singh divided the meeting into groups of four or five and asked each group to write down three ‘values’ – principles that they felt should underpin the work of the school. They gathered up all the suggestions and found there was considerable overlap. Mr Singh agreed to write up their ideas ready for the next meeting.

A week later, they had another meeting. This time, each group started from the set of agreed principles and devised a vision statement. After much discussion, they came up with: ‘This is a school in which all children are valued and cared for, and have the opportunity to fulfil their positive potential.’

Notice how key stakeholders worked together in order to produce a vision statement. But in the time between his course and the two meetings, Mr Singh had spoken to a great number of different people, including parents and students. He had listened to their views and encouraged them to think about the core purpose of the school. In this way, the statement was a true reflection of the whole community.

Activity 3: Devising a vision statement in your school

In this activity you are going to make a plan that will enable you create a vision statement for your school.

- Spend two weeks doing as Mr Singh did, gathering information about your school and engaging teachers, parents, student and community leaders in conversations about what they think the school does well and what needs to improve. (The unit Perspective on leadership: leading the school’s self-review might give you some ideas.)

- In your Learning Diary, plan two joint meetings for the SMC and your teachers in order to identify your core values and create a vision statement.

5 From vision to action

The vision statement is important because it provides a frame of reference. Any actions undertaken by you and your staff can be checked against the statement ‘If I do this, will it contribute to our vision?’

A vision statement is a short statement that summarises what a school stands for and its intentions for the future. It is not detailed, but it can be expanded into a mission statement that defines (for the leadership team) the organisation’s purpose and main objectives.

It is helpful to clarify the difference between vision and mission statements (Table 2).

| Difference | Vision statement | Mission statement |

|---|---|---|

| Detail | Outlines where you want to be Communicates both purpose and values | Talks about how you will get to where you want to be Defines the purpose and primary objectives |

| Answer | Answers the question, ‘Where do we aim to be?’ | Answers the questions ‘What do we do?’ and ‘What makes us different?’ |

| Time | Talks about future | Talks about the present leading to the future |

| Function | Lists where you see yourself some years from now. Inspires and shapes direction | Lists the broad goals for which the school is formed Defines the key measures of success – the prime audience is the leadership team and stakeholders |

| Change | Will remain intact because it is about values, not just what you do | May change, but will derive from core values, pupil needs and vision |

| Developing a statement | Where do we want to be going forward? When and how? | Why do we do what we do? What, for whom and why? |

| Features of an effective statement | Clarity and lack of ambiguity Describing a bright future (positive) | Translates purpose and values into actions |

In Case Studies 2 and 3, once Mr Singh’s school had framed its vision statement (‘This is a school in which all children are valued and cared for, and have the opportunity to fulfil their positive potential’). He worked with his senior leadership team (which included his deputy and the chair of the SMC) and asked the question: ‘If this is our vision, what should we be doing to help realise it?’

The vision statement is fixed, but the mission statement and subsequent actions will depend on the context and the information gathered as part of the school’s self-review.

It is likely that any sort of review will lead to more actions than can be carried out! This is where having a clear vision statement is important, because it will help the school leadership team to prioritise their actions.

Based on the information that he had gathered, Mr Singh and his team realised that in order to ensure that all students had the opportunity to fulfil their potential, they needed to improve the quality of their teaching and take specific steps to support the education of their female students. Two priorities were identified:

- increasethe number of female student admissions in the school

- improve the quality of teaching across the school.

These priorities led to some specific actions to:

- seek funding and district support for a new toilet for female students

- start a village recruitment campaign for female studentsled by alumni of the school who are now successful young women studying for their degree or working in their chosen field

- identify female teaching champions in the school to seek out good practice, support challenged staff and mentor new recruits

- use the TESS-India key resources to improve assessment for learning so that students are able to take responsibility for their own progress.

There are leadership units on self-review and on the school development plan that have more information, and activities to support self-review and development planning.

The purpose of the vision is to help school leaders to prioritise and identify the actions that should be included in their planning.

6 Monitoring progress towards the vision

Once a set of actions have been identified, it is the responsibility of the school leadership team to monitor those actions and ensure that they lead to school improvements. In the leadership units on reviewing and planning, you are encouraged to think in terms of a cycle of planning, action and review. All actions should be monitored and evidence should be collected to inform the preparation of a new plan for the next year.

Periodically, as part of this process it will be necessary to revisit your vision statement and ensure that it remains ‘fit for purpose’. As the school improves or as government policy changes, new priorities will emerge and you may need to adjust your vision.

For the school leader, working effectively with the community and your teachers is very important. Getting people to do what you want them to may require a certain amount of skill and persuasion. But having a clear, agreed vision will always provide a reference point. If people disagree about which actions are most urgent, they can be discussed in the context of the vision, and priorities will emerge.

In this final case study, notice how Mr Nagaraju builds relationships with key stakeholders before embarking on the process of creating a vision statement and then involving them in its monitoring.

Case Study 4: Mr Nagaraju wins the hearts of the teachers

Mr Nagaraju was moved by the district education office to lead a small rural secondary school. The school was not highly thought of by the local community because a previous school leader had misappropriated its resources. The next school leader found the level of mistrust in the community too stressful and left the job after only two years. Mr Nagaraju realised that in taking over the leadership of the school he had a significant challenge ahead.

In his first term, Mr Nagaraju watched and listened. He walked around the school during the school day, interacted with students and parents at the beginning and end of each day, and listened to the concerns of the teachers and community leaders. He realised that people were too demoralised and disappointed to start the process of developing a vision.

He decided that the most important people to have on his side were the teachers. He listened to their concerns and tried to make their lives easier, for example by making available equipment that was in locked cupboards, offering teachers cartoons in English on his laptop for language development, and organising solar lamps for students in Class X who did not have electricity at home so that they could study in the evenings. At the end of his first year, the exam results improved.

During his second year at the school, morale improved. The teachers appreciated the support from Mr Nagaraju and the local community became increasingly interested in the school. During the first term of his second year, he held a series of meetings that led to the identification of a vision statement. He had a sign made, with the statement on, to put on the school gates. By the end of the next term, the teachers and the SMC had identified a set of priorities and a development plan was in place.

The vision statement became more than a school motto; it became a tool for monitoring. Mr Nagaraju organised a quarterly meeting with two members of the SMC. Parents were invited and older students organised much of the event. Mr Nagaraju used these meetings to monitor just how far students and parents felt included in all aspects of the school, as this was at the core of the vision. He introduced a novel way of getting parents to vote on certain matters using bottle tops, with entrance and exit polls on different issues. For example, on the way in, parents put a bottle top in one container if they were happy with the levels of homework, or in one of two other buckets if they thought it was either too much or too little. On the way out, the parents put their bottle tops (which had been counted and recorded by the students in the meantime) into one of several labelled containers to vote for the priority of the coming year.

Figure 4 A voting system.

Pause for thought Reflect on what you have learned in this unit. Think about your school and the people around you.

Note down your answers in your Learning Diary. |

7 Summary

Research into successful schools shows that their leaders have a clear vision for what they want their school to achieve. A vision statement provides a roadmap for the school’s direction and a framework for offering students the best possible education. An effective vision statement will involve all stakeholders and will be obvious to teachers and students, as well as visitors to the school, because efforts will be purposeful. Teachers and students not only know and understand the vision, but they also commit to its implementation and success.

Developing an effective vision should not be hurried and should be an inclusive activity where everyone feels consulted and involved. Involving stakeholders promotes ownership, because without everyone signing up to the vision, it becomes a meaningless, unrepresentative activity. If they are united in the development and monitoring of a school’s vision, the students, teachers and parents can feel united in the shared aspiration for a better future together.

This unit is part of the set or family of units that relate to the key area of perspective on leadership (aligned to the National College of School Leadership). You may find it useful to look next at other units in this set to build on your knowledge and skills:

- Leading the school’s self-review

- Leading the school development plan

- Using data on diversity to improve your school

- Planning and leading change in your school

- Implementing change in your school.

Additional resources

- Mission and vision statements: http://www.mindtools.com/ pages/ article/ newLDR_90.htm#sthash.ZZXtOrAn.dpuf

- Improving a school: http://tinyurl.com/ pb3tpy8

- Creating a vision: http://tinyurl.com/ nl7g2wy

- ‘Values into action’ by Kaushi Silva: http://tinyurl.com/ mx598wq

- SoundOut: http://www.soundout.org/ publications.html

References

Acknowledgements

Except for third party materials and otherwise stated below, this content is made available under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike licence (http://creativecommons.org/ licenses/ by-sa/ 3.0/). The material acknowledged below is Proprietary and used under licence for this project, and not subject to the Creative Commons Licence. This means that this material may only be used unadapted within the TESS-India project and not in any subsequent OER versions. This includes the use of the TESS-India, OU and UKAID logos.

Grateful acknowledgement is made to the following sources for permission to reproduce the material in this unit:

Table 2: adapted from http://www.diffen.com/ difference/ Mission_Statement_vs_Vision_Statement.

Every effort has been made to contact copyright owners. If any have been inadvertently overlooked the publishers will be pleased to make the necessary arrangements at the first opportunity.

Video (including video stills): thanks are extended to the teacher educators, headteachers, teachers and students across India who worked with The Open University in the productions.