Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Thursday, 5 February 2026, 7:35 AM

TI-AIE: Transforming teaching-learning process: promoting inclusion in your school

What this unit is about

Over the past two to three decades, governments across the world – including those of India – have stated their commitment to addressing gender and social biases in all areas of education. This period is characterised by radical changes in what constitutes quality education and how this can be provided for by teachers. The changing trends can briefly be summarised as:

- a greater emphasis on removal of disparities

- equitable education for all

- child-centred, need-based education

- maximising the participation of every child in the learning process.

These trends are reflected in major Indian policy documents, including the National Policy on Education (NPE, 1986), the National Curriculum for Elementary and Secondary Education (1988), and the Revised NPE and Program of Action (1992), among others.

More recently, the National Curriculum Framework (NCF) of 2005 provides a comprehensive approach, including ways of providing an inclusive education of quality to all children. It clearly highlights the need for teachers to:

- be sensitive to each child’s unique requirements

- provide child-centred, socially relevant and equitable teaching/learning

- understand the diversity in their social and cultural contexts.

No teacher can be successful today professionally without understanding or being sensitive to the numerous demands and expectations that students bring with them to schools. They should be able to engage and provide meaningful learning opportunities to all students, irrespective of class, caste, religion, gender and disability. The Right to Education Act 2009 (RtE) further strengthens and reinforces this stance for making quality education a reality for all students, irrespective of gender and social category, by laying down in detail the acceptable norms related to the physical and learning environments, the curriculum, and pedagogic practices.

There is a significant body of research that confirms that the skills, attitudes and motivation of teachers can significantly raise the engagement, participation and achievement of children belonging to disadvantaged and marginalised communities.

The role of the school leader is critical in promoting the delivery of equitable education by teachers in an inclusive school classroom setting . First and foremost, it is imperative that the school leader:

- believes that outcomes can be equitable, whatever the individual starting points of their students

- enthuses the staff and students to raise achievement in all students

- measures the success of students by more than their academic achievement.

As a school leader, you should be aware of the United Nations Charter on the Rights of the Child (1989), a significant driver for embracing diversity that legislates for every member state to provide education for all its children. It is your responsibility as a school leader to lead , promote and nurture inclusive attitudes and behaviours in your school community.

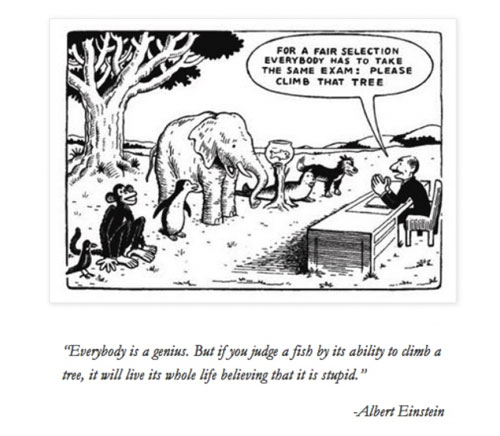

Figure 1 Promoting inclusion in your school.

Learning Diary

During your work on this unit you will be asked to make notes in your Learning Diary, a book or folder where you collect together your thoughts and plans in one place. Perhaps you have already started one.

You may be working through this unit alone, but you will learn much more if you are able to discuss your learning with another school leader. This could be a colleague with whom you already collaborate, or someone with whom you can build new relationship. It could be done in an organised way or on a more informal basis. The notes you make in your Learning Diary will be useful for these kinds of meetings, while also mapping your longer-term learning and development.

What school leaders can learn in this unit

- To develop a shared understanding of diversity, equity and inclusion with your staff.

- To prioritise actions to improve learning outcomes for all your students.

- To collaborate with others to plan and execute actions that address disadvantage or exclusion in your school.

- The importance of evaluating the impact of your interventions.

1 Promoting equity and inclusion through leadership

It is a cause for celebration and pride that the population of India is so diverse. The word ‘diverse’ means ‘showing a great deal of variety’ or ‘very different’. Variety not only adds interest to life, but also offers a greater number of solutions and possibilities in a complex and changing world.

The diversity in a school may be related to a number of factors such as language, ethnicity, gender, caste, class, income levels, physical abilities, housing, age or previous schooling. No two students will have the same starting point when they join a class, or the same way of learning or connections with the curriculum. A teacher who appreciates and values different backgrounds , culture and experiences is more likely to engage students in learning that is meaningful to each of them.

The NCF quotes from the NPE:

To promote equality, it will be necessary to provide for equal opportunity for all, not only in access but also in the conditions of success. Besides, awareness of the inherent equality of all will be created through the core curriculum. The purpose is to remove prejudices and complexes transmitted through the social environment and the accident of birth.

This policy language can be difficult to transfer to the setting of your school and classrooms. Therefore, it is the school leader’s responsibility to help their staff and the wider school community to address issues relating to diversity, equality and inclusion. This can be seen to involve three initial steps:

- Ensuring that all the teachers and the wider school community understand diversity, equity and inclusion issues within the school context. This includes knowing what the implications are for student outcomes and their practice.

- Collaboratively plan and carry out interventions or actions to address issues of inequality or exclusion. Understand how actions to change their own teaching practices and/or learning opportunities can make a difference.

- Understand how changes to teaching, learning or pastoral support will be monitored to ensure that they have a positive effect on student learning.

If you have read the unit Using data on diversity to improve your school, you will have already thought about how data can highlight diversity issues within your school context, and begun to develop priority areas for your school. The data you have collected and the priority areas you have identified will be critical in understanding how to lead your staff to be more inclusive in their teaching practices.

2 Helping others to understand diversity, equity and inclusion

You may find that some of your staff already have a good grasp of the terminology of inclusion – although some may not. Many will need further professional development to understand the relationship between diversity, your particular school context and the specific impact it has on student outcomes.

You may therefore need to spend time helping staff, and the wider community to understand the implications of this agenda for them as an individual. You could to do this by organising a small working group to make some initial changes before engaging the wider school, or addressing it as a whole school issue from the beginning. Whichever approach you take, you will need some tools to help you introduce the topic and to help staff to develop an understanding of what equality, diversity and inclusion mean for them. Resource 1, ‘Including all’, may be helpful to share with your colleagues.

Artiles et al. (2006) identify four dimensions of inclusion in the education setting that can be useful as an initial starting point:

- Access: Where the barriers to attendance include a disability or medical condition, poverty (not being able to afford uniform or fees for school, having to earn money for the family, no home study space), location (the journey to school is too arduous or dangerous for their age), caring responsibilities, or a lack of priority given to education due to cultural factors.

- Acceptance: The ‘status’ that learners are given once they are in school, which can be affected by teacher attitudes. Teachers should have the expectation that all learners are individuals and will be able to succeed regardless of background factors.

- Participation: Learning is a social activity; knowledge is constructed as we participate in activities with others and come to joint meanings with others. Learners must be given the opportunity to participate with each other and in interactions with teachers.

- Achievement: ‘Inclusion’ does not mean that all learners will achieve to a similar level. In an inclusive context, ‘achievement’ means that all learners have the opportunity to demonstrate their educational achievements in many different contexts and not just at fixed and formal national tests. Teachers must allow students to show their varied skills, abilities and knowledge so that their achievement can be recognised and valued within the community.

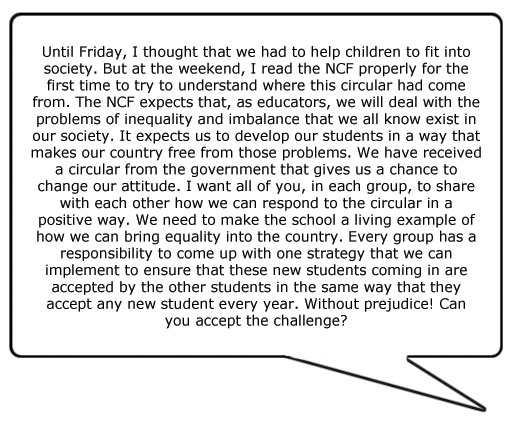

Figure 2 offers an amusing example of how easy it is to exclude individuals or groups by the tasks that are set.

Figure 2 The tasks you set must promote inclusion.

The animals in Figure 2 are as diverse as the students in your classrooms. It is important to recognise their differences in a positive light and not to give them tasks in a way that disadvantages some and favours others. In the figure it is obvious which animal is going to succeed at the task that has been set; a class of students is very similar. Teachers often know when setting a task which of the students in a class is going to succeed.

However, It is not only in tasks that some students may be disadvantaged. The school environment may mean that some students do not have equal access or that they struggle unnecessarily (for example, in using bathrooms or washroom facilities). These additional hurdles can cause a student stress and may even mean that they do not attend school due to anxiety about being different. It therefore becomes important to ‘normalise’ difference so that there is no shame or embarrassment associated with have additional needs or adaptations.

Activity 1: Starting a conversation about the implications of inclusion on practice

Reflect on Artiles et al.’s dimensions of inclusion and the cartoon in Figure 2. How might you use these resources to start a conversation with your staff about promoting inclusion in your school? Consider what opportunities they provide for discussing:

- your particular school context

- the implications for particular subject areas

- the implications for the type of teaching and learning that occurs (including assessments).

Discussion

You may have realised that creating an inclusive learning environment is interwoven with teaching that promotes active, individually tailored and appropriate learning for the particular needs of the class. It is highly unlikely, for example, that a course designed around all students working through a textbook with a final written exam will create an inclusive environment where all students achieve their potential.

You may have reflected in Activity 1 on how particular subjects have specific inclusion issues relating to certain groups of students, or that in your context there is one overriding factor that impacts on students’ access to the curriculum.

Whatever your thoughts, these resources can provide a starting point for the conversation about what it means to be inclusive both in attitude but also in actions within the classroom and school environment. In doing so it is well worth recognising and drawing on the fact that many of your staff may have personal experiences of disadvantage or exclusion. If individuals don’t have personal experience, they may know someone who has, or may be able to imagine their feelings in a scenario. Using these experiences can be a powerful learning tool to facilitate changes in attitudes and beliefs. Now try Activity 2, while considering how such an activity might support you and your staff in developing a more inclusive culture in your school.

Activity 2: Using personal experience

Reflect on a time when your own difference (caste, education, language, colour, gender, etc.), or perhaps the difference of someone you are close to or know well, had a negative or not so desirable effect on school experience. Answer the following questions:

- How did it make you feel to be excluded or discriminated against by others?

- How did you deal with such a situation?

- What support would you have liked ?

- Did you get the support you wanted?

- What do your answers highlight about how students who feel excluded or discriminated against might feel in your school?

Discussion

You may feel that you have experienced only a little discrimination earlier on in your life, or maybe you had not thought about it until now as being ‘discrimination’ and had just accepted some unfair treatment as ‘that’s the way it is’. However, you would have surely witnessed significant acts of injustice towards other students, and maybe you were complicit in it. Looking back, we have the benefit of hindsight to see these things. You probably had feelings of frustration, injustice or powerlessness.

As a student it can feel very difficult to challenge authority, even when you feel it is unjust. Maybe the experience had the effect of demotivating you as you were disregarded or overlooked? There may have been a particular teacher who was more equal and fair in their practice and you felt supported in their lessons, or that you got support from your family, who encouraged you to keep trying. It is hard to keep trying to learn if the school appears uninterested in what you do, and this will in some way affect your success.

There can be different levels of discrimination operating in a school and the school leader and teachers needs to be alert to both. Personal discrimination may come about through an individual’s conscious or unconscious prejudice. For example, there might be a scenario where a student is not picked for the school cricket team, despite his obvious abilities. This could be because the teacher does not want a boy from his village in the team and believes that the other boys will feel the same.

But there can be a more pervasive and hidden level of discrimination in institutions that can impact significantly on a school culture. Institutional discrimination is often unquestioned, especially if becomes the normal way of working. For example, there may be a widely held belief that girls are no good at mathematics or science. This is obviously a falsehood, and yet girls are not encouraged to pursue these subjects beyond the level of the mandatory curriculum. Another example might be the shared belief that students from a particular ethnic group will only ever have manual jobs, so there is little point in extending their appreciation of literature and the arts: the poets and artists in this group are therefore never identified or nurtured. Institutional discrimination operates on the assumption that everything is all right as it stands and that nothing needs to change.

As a leader, you should learn to spot and challenge institutional discrimination wherever you find it by focusing on equality in learning outcomes for all your students. Challenging ‘norms’ can be very hard. Try to imagine things differently and ask yourself if you have good evidence for your assumptions. For example, take the (wrong) assumption about girls not being good at mathematics. You might ask yourself: What have I read that tells me this? Do I know any good female mathematicians? If girls are never given the opportunity to learn advanced mathematics, how can they show their abilities?

Activity 3: Education as a gateway to a different life

Below is an extract from Wikipedia about the 11th President of India, Dr A.P.J. Kalam. As you read it, think about how he was able to succeed academically, despite coming from a socio-economically challenged family. As he continued his education it was not always easy and he did not always succeed, but he showed incredible resilience and self-belief.

Avul Pakir Jainulabdeen Abdul Kalam (born 15 October 1931), usually referred to as Dr. A.P.J. Abdul Kalam, is an Indian scientist and administrator who served as the 11th President of India from 2002 to 2007.

Abdul Kalam was born on 15 October 1931 in a Tamil Muslim family to Jainulabdeen, a boat owner and Ashiamma, a housewife, at Rameswaram, located in the Indian state of Tamil Nadu. He came from a poor background and started working at an early age to supplement his family’s income. After completing school, Kalam distributed newspapers in order to contribute financially to his father’s income. In his school years, he had average grades, but was described as a bright and hardworking student who had a strong desire to learn and spend hours on his studies, especially mathematics.

After completing his school education at the Rameshwaram Elementary School, Kalam went on to attend Saint Joseph’s College, Tiruchirappalli, then affiliated with the University of Madras, from where he graduated in physics in 1954. Towards the end of the course, he was not enthusiastic about the subject and would later regret the four years he studied it. He then moved to Madras in 1955 to study aerospace engineering.

He is quoted to have said in his autobiography Wings of Fire (2002): ‘I inherited honesty and self-discipline from my father; from my mother, I inherited faith in goodness and deep kindness, as did my three brothers and sisters.’

Having read the extract, reflect on the following questions:

- Where do you think these qualities came from and how were they nurtured? Where might he have got his inspiration and support from to study so hard? Think about his immediate family, his community and his schooling.

- Are there other case studies that could promote inclusion and aspiration among your staff and students? These could perhaps include students from a range of backgrounds who have left your school and gone on to be very successful in a range of fields, or well-known personalities who overcame barriers. How might you use these case studies to challenge attitudes and behaviour?

The extract above describes Dr Kalam’s inheritance from his parents; he also mentions that his siblings inherited the same. Yet most of his extended family did not desire to enter higher education or achieve academic success. Alongside the influence of his parents, there were perhaps members of his community who encouraged him, liking the prospect of him rising from his humble roots to represent them in a wider context – little did they know that he would become President of India. It is also likely that schooling played a major in Dr Kalam’s achievements. Perhaps he had teachers who respected and encouraged him, regardless of his lowly status. Perhaps the schools worked hard at helping students progress to the next level of education, building aspiration in all.

Using case studies, particularly ones local to the community, is a powerful tool for changing attitudes. Displaying case studies, using them in class as part of curriculum activities, inviting in guest speakers to discuss their successes and how they overcame barriers, and discussing the lessons that can be learned from individual stories, can all be useful ways of engaging staff and students in discussions about inclusivity.

3 Prioritising actions to improve learning outcomes

Many factors can affect access to learning, such as attendance, being able to afford a uniform, students’ ability to get to school or the limitations of washroom facilities at school. Alternatively students may experience disadvantage in the classroom that affects their learning due to the teachers’ attitude, the methods and materials used, and the delivery of the syllabus while teaching.

You have become aware of the hard work put in by students who perceive that they are different and need to ‘fit in’ to the demands of school. These demands could be that students must write neatly, or read from a blackboard four metres away, or that they sit and listen for long periods of time.

Students react to these (and other) demands with a wide range of responses, spanning from ‘with ease’ to ‘with enormous difficulty’. For some students, meeting these demands requires minimal effort. In other cases, they are able to do so only when supported by significant people in their lives (usually parents and teachers).

It is clear that schools need to move from a position of seeing such coping strategies and difficulties as ‘inevitable’. The NCF is putting the onus of change on the school and the educator when stating that:

a critical function of education for equality is to enable all learners to claim their rights as well as to contribute to society and the polity. Thus, in order to make it possible for marginalised learners, and especially girls, to claim their rights as well as play an active role in shaping collective life, education must empower them to overcome the disadvantages of unequal socialisation and enable them to develop their capabilities of becoming autonomous and equal citizens.

It is essential to analyse the link between different groups of students in your school and their differential access to learning opportunities. The realisation that exposure and practice was a large part of how some students appeared to learn some subjects quickly changed the way that teaching was viewed. The art of good teaching moved from the mere delivery of information to employing strategies that enabled learners to find their own ways to a similar learning outcome.

Activity 4: Analysis of equality of access to learning

Take a look at Table 1, which is an extract from Mr Sharma’s diary as he reflected on the range of diversity in his school and how that might be linked to the students’ experiences of learning. Mr Sharma wanted to identify the range of diversity, how many students were involved and how that impacted on inclusion as per Artiles et al.’s dimensions. Recognising that learning does not just happen in school, he also thought about how the students’ home situation affected their learning. Mr Sharma used the data he had gathered in the unit Using data on diversity to improve your school to inform his planning.

| A | B | C | D | E |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| # | Type of diversity | Percentage of students | Estimation of percentage access, acceptance, participation and achievement in learning at school and home | Actions, interventions or staff to collaborate with |

| 1 | Boys | 80 | 90%: Boys are provided with opportunities for growth and development to build their earning capacity, they often sit at the front of the class and male teachers in particular favour them | |

| 2 | Girls | 20 | 30%: Girls’ education is not seen as an investment that will provide returns to the family; they do not always attend and may not have equipment such as paper and pens | |

| 3 | Learning disabled | 3 | 20%: There are no experts available to help teachers with strategies that work for these children; their difficulties are not always obvious until quite late, or parents are embarrassed | |

| 4 | Upper band of the socio-economic spectrum | 15 | 60%: Families buy support in the form of tuition; some students know they will join the family business and so are low on motivation; students have books and papers at home, and maybe technology to help with learning | |

| 5 | Lower band of the socio-economic spectrum | 85 | 40%: Little home support for reading and writing; expected to help with chores in the fields and at home; poor attendance; poor parental engagement; lack of learning materials and resources | |

| 6 | Physically disabled | 2 | 30%: Education for the disabled is not seen as an investment that will provide returns to the family; no adaptations to the physical environment to assist access; difficulty getting to school and other places in the community | |

| 7 | Muslim students in the school | 10 | 50%: Education is valued but competes with learning a craft and with religious education; little interest in girls learning beyond requirements for a good wife | |

| 8 | Hindu | 60 | 80%: Boys are more likely to receive support from the family than girls | |

| 9 | Deprived community (SC/ST)* | 30 | 40%: Low access to home support; expected to help with chores in the fields and at home; undernourished and lacking energy; low self-esteem |

Using Mr Sharma’s table, create a similar one in your Learning Diary (or use the template in Resource 2) for your school. It might prove useful to complete this activity with a group of staff to get a range of ideas and perspectives on how the students experience and achieve within different areas of the school.

In the first column, list the different types of diversity that you either observe in students coming to your school or have identified through data analysis in the unit Using data on diversity to improve your school. You might like to consider such factors as:

- ethnic group

- community

- socio-economic status

- caste

- gender

- language or dialect

- religion and belief systems

- size and structure of family

- history of education in family

- health

- geographical location.

If you have completed the unit Using data on diversity to improve your school, you could use the data you have collected to complete columns B and C, and begin column D. Estimation could be used to start to build a picture, but you should be careful about drawing conclusions from these until you have investigated further.

Column D allows you to begin to think about how different groups access, are accepted, participate in learning and achieve. This will just be an initial reaction and you will need to work collaboratively with your staff to identify these issues more fully over time.

Column E (not yet covered in Mr Sharma’s template) will help you to begin to think about steps for addressing issues of inclusion in your school. This final column allows you to make notes about any ideas you have for actions to take to address the issues you identify.

The categories that Mr Sharma used relate to his school. He looked at majorities and minorities in order to reach some generalisations about each category. He only singled out Hindus and Muslims and might at some point look at the characteristics of other religious groups.

Discussion

You may have looked at Mr Sharma’s list and realised that the Hindu male student from a reasonably well-to-do family has the best chance of getting access to learning. Does this correspond with your table? It probably became apparent that a female student has fewer opportunities to learn if she is from the economically weaker section, a minority community or the scheduled tribes and castes. If she has a physical disability, she may never even make it to school. This introduces the idea of double or triple disadvantage, and you should be alert to students who fall into more than one category.

You may have been interested to note that Mr Sharma did not make the easy assumption that he did not have to be concerned about an apparently ‘advantaged’ group – note what he identified in relation to the learners in the fourth group (with a higher socio-economic status): he was concerned that the students might not be engaged in learning, something that is worrying for a teacher. At the same time, what this table does not show is the fact that students may identify with several groups – there will be multidimensionality in their profile. Thus it is important to acknowledge that if you put (for examples) female students into a group, it will be very diverse, as will a group identified as having a particular religious identify. It is important to see individuals within the group and to identify their particular position within the learning of the school.

It is most likely that there will be two or three issues that you identify as having the greatest impact on students’ learning outcomes, and these will become your priority areas. You may have already identified these in the unit Using data on diversity to improve your school and begun the process of collaboratively developing a strategic plan to address these with your staff. But do not feel that every action needs to be a big step; initially you might make very simple changes, such as seating arrangements in the classroom.

It is by using data and identifying priority areas that you can begin to collaborate with your staff to understand how making changes to the curriculum, teaching strategies, support systems or even just the way students, teachers and other adults in the community interact can create a more inclusive learning environment.

4 Collaborating with others to create a more inclusive learning environment

Changing attitudes, behaviours and systems to be more inclusive takes time and a consistent focus on why such changes are necessary for the good of the students’ learning. As a leader, you may have begun to change your own perspective and be modelling more inclusive attitudes and behaviours, but facilitating your staff to be more inclusive will only come if they are empowered at an individual level to think about the implications for their own practice, to hear of what others are doing and to share their thoughts. Inclusion will be most successful in improving learning outcomes if it is consistent across the school and embedded in every aspect of a student’s experience. Therefore it is essential that all staff are involved collaboratively in the process of planning and taking action.

Now read the story of Mrs Menon, a school leader who felt forced to take action to broach the equality, diversity and inclusion agenda in her school.

Case Study 1: Mrs Menon’ s staff meeting

An order had been received by Mrs Menon, the principal of an elementary school, regarding a 25 per cent reservation for students from economically deprived families. She and her colleagues felt that 25 per cent of the new students must not be forced on their school from the deprived socio-economic section. Yet the order had arrived in the form of a circular that she could not ignore. She would have to break the news to her board. They would ask her how she was going to do this. It was Friday, and she had no plan.

By the time she boarded the bus going home, Mrs Menon had sent a copy of the circular to her staff, with a note requesting them to stay on after school on Monday for a meeting about the issue. She sent a similar note to the non-teaching and office staff. She picked up a copy of the National Curriculum Framework and the RtE from her office cupboard. She was going to read them over the weekend and prepare for the meeting, which could be stormy.

It was a very different Mrs Menon who entered school after the weekend. Although she regularly walked around the school on a Monday, this time she seemed to be looking for something particular. During a class observation she asked the students a lot of questions that were very different compared with those she usually asked during her rounds. Then when she went through their notebooks, she asked for the learning resources and seemed more interested in their content than in what the students had written.

That afternoon, Mrs Menon began the meeting in a new way. She asked her teachers to sit in groups. Each group was then joined by one or two non-teaching staff members. She asked them to listen to some passages she read out from the NCF that spoke of the educator’s responsibility in bringing about social change. She had photocopied the relevant passage and handed it out to the groups. At the end of the readings, she said:

There was silence in the staff room. Then one teacher said, ‘Yes, ma’am, of course we can accept the challenge.’ And then everyone got to work.

Mrs Menon went from group to group, listening intently to the discussions, noting the teachers who were speaking with passion. She knew they would be her future champions and that she would need them to speak up often. At the end of the meeting, Mrs Menon was armed with enough strategies to answer the queries from her board. By changing the way she ran her staff meeting, Mrs Menon had involved her staff in the issues and solutions, modelling implicitly an inclusive approach and generating a range of strategies that she may never have thought of herself.

Activity 5: Collaborating to explore new approaches

Reflect on Case Study 1 in your Learning Diary by considering the following questions:

- Mrs Menon underwent a significant change in her own attitudes towards the issues that the circular raised. Consider what she would have done over the weekend to instigate this change. How easy or difficult do you feel it would have been for her to make this change? What factors might hinder someone else in that situation from being able to make the same shift in their mindset?

- The staff at the meeting were also asked to make a significant change in their attitudes. What helped them to do this? If you were in the same situation, what arguments or resources could you draw on to help make the case to staff about the importance of changing their perspectives?

- What steps did Mrs. Menon employ in the meeting to empower each member of staff to work collaboratively?

- What have you learned from this case study that could help you in a similar scenario?

Discussion

You will have noticed that although Mrs Menon had reservations about including students from other groups in her school, she embraced the challenges and took a positive approach. She realised that to successfully accommodate these new students, she needed to prepare for their arrival and inclusion in the school.

We aren’t told what actions Mrs Menon took over the weekend that caused her own change in perspective, but we know she consulted official documentation. It is unlikely that this in itself will have caused a change in attitude, but may have put in sharp relief that she needed to engage and address these issues. However, we know that in keeping student achievement and participation in mind, Mrs Menon was open to having her opinions changed. Not everyone finds this easy, and there may be staff in your school who consciously or subconsciously fight against alterative perspectives or ways of thinking. In this particular case study there was an external factor driving the change and a short timescale that made Mrs Menon address her own attitude very quickly. However, it is likely that you will identify issues and address them over a longer period of time, giving you the ability to gradually introduce changes and ways of thinking, bringing around staff who have difficulty in making the transition.

Mrs Menon, we can suspect, knew it was going to be difficult to change the attitudes of her staff in such a short period of time, so she was clear with her staff about what was expected and sought out her allies. All research states clearly that the leader of the school has to be clear about the goals of education and that, by broadening their goals beyond exam results for the few to inclusive learning opportunities for all, a leader will build a school where students and staff value equity and relationships.

Did you notice that Mrs Menon asked her staff to embrace these new students ‘without prejudice’? That is a key request. We all have prejudices – sometimes grounded in bad experiences, but more often they are not founded on real evidence. It is important always to examine the basis for our prejudice in order to question its validity. Prejudice against ethnic groups, women or people with a disability is unfortunately very common, but schools can be a place where that prejudice is not accepted as valid. Mrs Menon tackled head on the prejudicial attitudes that she suspected were in her school, leading by example in reassessing and tackling her own prejudices.

You may also note that, as leader, Mrs Menon realised that she did not have to address ‘the problem’ all by herself: she used the resources – the ideas and skills – within the school to help that school community rise to the challenge together. And you will note also that she involved all members of that community. It is easy for us as teachers to discriminate against ‘non-teaching’ staff: they may not ‘teach’, but anyone who interacts with students are important partners in setting the tone of inclusion within the school community. Therefore, they offer a very valuable perspective that complements that of teaching colleagues.

Having got her staff to discuss the issues relating to a priority group of students and think about actions they could or should take collectively to ensure that these students achieved to their potential, Mrs Menon and her staff would then have to plan how to implement these changes. These changes will be context- and student-specific.

Activity 6: Baseline for an action plan

In Activity 5, Mr Sharma noted that, as well as being the object of prejudice, there were fewer learning opportunities for a female student from the economically weaker section of a minority community with poor access to education and awareness. Either use this example or choose a priority area you have identified for addressing inclusion in your school and think about what steps can be taken to address their needs. You will have started to think about this in Activity 6, but now is the time to make more concrete, specific action plans. You might want to work with another colleague on this to share perceptions and collaborate on appropriate actions. It may help if you consider doing the following.

Identify the girls from the economically weaker section of different minority groups in your school (or the students from your chosen priority). Identify the students, their class, subjects taken, the family and socio-cultural background, and the attendance and grades obtained in each subject. If you have a large number of students to focus on, then choose a case study group of, say, six to ten students to get a feel for the issues that they face.

- Consider the four dimensions of inclusion (access, acceptance, participation and achievement) to assess in what specific ways the students experience exclusion or disadvantage.

- Find some time from your busy schedule to sit in on some lessons with these students. Do not obviously make them the focus of your attention, but observe how they engage with learning. Ask yourself: Are they participating? What might be the barriers to their active participation? How might they be supported individually to participate more fully in the teaching–learning process?

- You may like to also to understand their background and home situation more holistically . Consider meeting the parents of these students. Have any of them met with you to speak about their child, or the difficulties that the child has faced in school? What is it they would like for their children? What support for their learning or what learning experiences do they receive at home?

- Arrange to talk to the students about their experiences in school and of their learning. You will need to carefully assess whether this is best done in a group situation or individually, and you must ensure that they feel relaxed and free to talk without fear of your reaction or of others finding out the specifics of what they have said. However, it is essential to hear directly from these students, as they are likely to have a very good grasp of the specific difficulties that they face and may be able to tell you what interventions will work.

Discussion

You are building the baseline for an individual education profile of each of the students. Although these students will have certain factors in common, it is very important not to treat them merely as a ‘set’. Each one may have other factors that also impact on their learning; differing personalities will also influence their readiness to learn and resilience. You will not therefore be looking for a single solution to address their needs and improve their learning, although there may be common themes that can be addressed as a single intervention.

Having thought in detail about a particular inclusion issue in your school, you are likely to have developed a good understanding of what is preventing the identified students from achieving their potential and have already identified the actions that need to be taken. Interventions or actions to create a more inclusive learning environment will be quite specific to your context but may involve the following:

- Considering how to create a stronger feeling of partnership between the student and teachers. This could involve empowering the students to speak up if they are having difficulty – which will help staff to understand how students are finding the learning – or for teachers to be more active in seeking feedback on how the students feel they are getting on.

- Developing systems to enable students to discuss personal circumstances that are having a negative impact on their learning.

- Adjusting the teaching methods, learning resources or assessment techniques to enable students to learn fully and effectively.

- Making changes to the school environment or systems to ensure that students feel safe, supported and provided with the maximum opportunity to succeed.

- Addressing specific attitudes or behaviours that have a negative impact on the culture of the school as a whole. This might be expressed through actions, how students are referred to or talked about (for example, if a lack of attainment in socio-economically deprived students is always accepted as the norm without any sense of ambition for better), or something as seemingly small as to how rewards or prizes are given (for example, if school prizes are only given for sport, and are always given to male students).

Activity 7: Making a strategic plan to promote inclusion

Now you will make a plan using this same example of ‘female students from the economically weaker section of a minority community with poor access to education and awareness as well as being the object of prejudice’, or the alternative group that you have identified for your school.

- Assign roles to teachers in identifying the students from different classes. Discuss what data is to be collected for purposes of planning. Also define how it is to be collected (for example, by interaction, observation, from parents or others), and how it is to be recorded.

- Study the data that you and your staff have gathered, and identify your collective vision of how the female students’ learning outcomes will be different over the next term and year.

- Develop a strategy to work with these students not as a homogenous group but on an individual basis , involving their parents and your staff towards this goal. Are there others who might help advise you on this?

- Identify the barriers to reaching your goal in terms of the skills, attitudes and the motivation of the female students, parents and the staff.

- Identify how to build the skills, attitudes and motivation that are needed (for example, training or coaching), and negotiate any resources that might be needed.

- Agree to a schedule to monitor progress and evaluate outcomes at the end.

- Schedule periodic meetings with those involved to discuss progress, provide feedback and review the adopted strategy.

This is not an activity that you can do alone. It needs to involve others on your team to ensure a whole-school approach. You may also consider getting the target students involved, or a student council, if you have such a body. You may also draw on the advice or expertise of a community group that understands issues relating to this specific group, thereby getting the community involved.

5 Evaluating impact

Whatever the challenge for equity that you are grappling with in your school, you need to establish a baseline as your starting point before you make a plan. This baseline is an honest, factual assessment of the situation that will quantify the extent and characteristics of the inequality that you are going to tackle. You can then track your progress in order to evaluate the impact of your interventions and resource allocations because you will be able to demonstrate how far the situation changes from your baseline.

Evaluating the impact of your actions will take two forms: data evaluation (which will include attendance and attainment results) and information about the experiences of the group. For instance, if we use the example of ‘female students from the economically weaker section of a minority community with poor access to education and awareness as well as being the object of prejudice’, you might find out if the female students are becoming more vocal as they experience being heard, feeling more valued as they experience respect, and through data analysis that they have improved their academic achievement.

Think about how you might gather your evidence in an inclusive way. You might like to consider talking to the students themselves, or asking them to interview each other and then present a report to you.

The purpose of evaluation is to ensure that the actions you have taken have led to better learning outcomes but also to enable you to learn from the process and identify what could be improved if you were to repeat it. It is highly likely that if you are tackling issues of inclusion that have a significant effect on attainment in your school that it will never stop being a priority. Instead you will be evaluating one intervention and identifying further actions that could be taken to improve the situation even further. In this way the process is likely to be circular.

In such a long-term strategic planning and evaluation cycle you will need to maintain your staff’s commitment and enthusiasm towards making changes in attitudes and behaviours. Sharing the results of evaluations with the staff is critical. There is nothing better to keep the staff interested and motivated as letting them know how you are tracking the impact they have had. Small steps towards a larger goal need to be recognised when the ambition is great. Equally, sharing evaluations with staff shouldn’t be a one-way process. They need to contribute to the evaluation process and help you to identify the next steps to be taken to further address the issues . For instance, they can ask: How did they find the changes that were made? What have they noticed about the learning of the students involved?

Developing inclusive practices takes time and a lot of effort. If you have successes, writing them up as case studies or organising opportunities to share your work with others either in the school or with other schools is highly valuable. In return, you may find others have addressed similar issues to your own priority areas and have some tried and tested ways of addressing them that you can then learn from.

6 Summary

In this unit you have learnt how to promote inclusion by addressing diversity and differences among students in a practical manner so that each student is provided with equitable educational opportunities and participates in learning in your school. This is no doubt a huge task to be done in addressing the inequalities experienced by many students in their everyday lives. But in schools there is the real opportunity to start moving towards equality and bringing about change in their lives by promoting an inclusive approach to learning, shared by the whole staff team and observed by the students who can learn to respect and value their peers.

It is you as the school leader who can do a great deal, as you are uniquely placed to influence and bring about the required change in the lives of many hundreds of students so that they make the most of their abilities and achieve their full potential. This requires courage, critical analysis, ambition and honest evaluations. If the steps seem to be too large, start small and build a school with a reputation for fairness and equality that you can be proud of. Keep your end goal in mind – that you want to create a school where the principles of the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child (Article 29) hold true and your school community can be proud to:

- develop every student’s personality, talents and abilities to the full

- encourage every student’s respect for human rights, as well as respect for their own and other cultures.

This unit is part of the set or family of units that relate to the key area of transforming teaching-learning process (aligned to the National College of School Leadership). You may find it useful to look next at other units in this set to build your knowledge and skills:

- Leading improvements in teaching and learning in the elementary school

- Leading improvements in teaching and learning in the secondary school

- Leading assessment in your school

- Supporting teachers to raise performance

- Leading teachers’ professional development

- Mentoring and coaching

- Developing an effective learning culture in your school

- Managing resources for effective student learning

- Leading the use of technology in your school.

Resources

Resource 1: Involving all

What does it mean to ‘involve all’?

The diversity in culture and in society is reflected in the classroom. Students have different languages, interests and abilities. Students come from different social and economic backgrounds. We cannot ignore these differences; indeed, we should celebrate them, as they can become a vehicle for learning more about each other and the world beyond our own experience. All students have the right to an education and the opportunity to learn regardless of their status, ability and background, and this is recognised in Indian law and the international rights of the child. In his first speech to the nation in 2014, Prime Minister Modi emphasised the importance of valuing all citizens in India regardless of their caste, gender or income. Schools and teachers have a very important role in this respect.

We all have prejudices and views about others that we may not have recognised or addressed. As a teacher, you carry the power to influence every student’s experience of education in a positive or negative way. Whether knowingly or not, your underlying prejudices and views will affect how equally your students learn. You can take steps to guard against unequal treatment of your students.

Three key principles to ensure you involve all in learning

- Noticing: Effective teachers are observant, perceptive and sensitive; they notice changes in their students. If you are observant, you will notice when a student does something well, when they need help and how they relate to others. You may also perceive changes in your students, which might reflect changes in their home circumstances or other issues. Involving all requires that you notice your students on a daily basis, paying particular attention to students who may feel marginalised or unable to participate.

- Focus on self-esteem: Good citizens are ones who are comfortable with who they are. They have self-esteem, know their own strengths and weaknesses, and have the ability to form positive relationships with other people, regardless of background. They respect themselves and they respect others. As a teacher, you can have a significant impact on a young person’s self-esteem; be aware of that power and use it to build the self-esteem of every student.

- Flexibility: If something is not working in your classroom for specific students, groups or individuals, be prepared to change your plans or stop an activity. Being flexible will enable you make adjustments so that you involve all students more effectively.

Approaches you can use all the time

- Modelling good behaviour: Be an example to your students by treating them all well, regardless of ethnic group, religion or gender. Treat all students with respect and make it clear through your teaching that you value all students equally. Talk to them all respectfully, take account of their opinions when appropriate and encourage them to take responsibility for the classroom by taking on tasks that will benefit everyone.

- High expectations: Ability is not fixed; all students can learn and progress if supported appropriately. If a student is finding it difficult to understand the work you are doing in class, then do not assume that they cannot ever understand. Your role as the teacher is to work out how best to help each student learn. If you have high expectations of everyone in your class, your students are more likely to assume that they will learn if they persevere. High expectations should also apply to behaviour. Make sure the expectations are clear and that students treat each other with respect.

- Build variety into your teaching: Students learn in different ways. Some students like to write; others prefer to draw mind maps or pictures to represent their ideas. Some students are good listeners; some learn best when they get the opportunity to talk about their ideas. You cannot suit all the students all the time, but you can build variety into your teaching and offer students a choice about some of the learning activities that they undertake.

- Relate the learning to everyday life: For some students, what you are asking them to learn appears to be irrelevant to their everyday lives. You can address this by making sure that whenever possible, you relate the learning to a context that is relevant to them and that you draw on examples from their own experience.

- Use of language: Think carefully about the language you use. Use positive language and praise, and do not ridicule students. Always comment on their behaviour and not on them. ‘You are annoying me today’ is very personal and can be better expressed as ‘I am finding your behaviour annoying today. Is there any reason you are finding it difficult to concentrate?’, which is much more helpful.

- Challenge stereotypes: Find and use resources that show girls in non-stereotypical roles or invite female role models to visit the school, such as scientists. Try to be aware of your own gender stereotyping; you may know that girls play sports and that boys are caring, but often we express this differently, mainly because that is the way we are used to talking in society.

- Create a safe, welcoming learning environment: All students need to feel safe and welcome at school. You are in a position to make your students feel welcome by encouraging mutually respectful and friendly behaviour from everyone. Think about how the school and classroom might appear and feel like to different students. Think about where they should be asked to sit and make sure that any students with visual or hearing impairments, or physical disabilities, sit where they can access the lesson. Check that those who are shy or easily distracted are where you can easily include them.

Specific teaching approaches

There are several specific approaches that will help you to involve all students. These are described in more detail in other key resources, but a brief introduction is given here:

- Questioning: If you invite students to put their hands up, the same people tend to answer. There are other ways to involve more students in thinking about the answers and responding to questions. You can direct questions to specific people. Tell the class you will decide who answers, then ask people at the back and sides of the room, rather than those sitting at the front. Give students ‘thinking time’ and invite contributions from specific people. Use pair or groupwork to build confidence so that you can involve everyone in whole-class discussions.

- Assessment: Develop a range of techniques for formative assessment that will help you to know each student well. You need to be creative to uncover hidden talents and shortfalls. Formative assessment will give you accurate information rather than assumptions that can easily be drawn from generalised views about certain students and their abilities. You will then be in a good position to respond to their individual needs.

- Groupwork and pair work: Think carefully about how to divide your class into groups or how to make up pairs, taking account of the goal to include all and encourage students to value each other. Ensure that all students have the opportunity to learn from each other and build their confidence in what they know. Some students will have the confidence to express their ideas and ask questions in a small group, but not in front of the whole class.

- Differentiation: Setting different tasks for different groups will help students start from where they are and move forward. Setting open-ended tasks will give all students the opportunity to succeed. Offering students a choice of task helps them to feel ownership of their work and to take responsibility for their own learning. Taking account of individual learning needs is difficult, especially in a large class, but by using a variety of tasks and activities it can be done.

Resource 2: Reflecting on diversity

| A | B | C | D | E |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| # | Type of diversity | Percentage of students | Estimation of percentage access, acceptance, participation and achievement in learning at school and home | Actions, interventions or staff to collaborate with |

|

|

| ||

| ||||

| ||||

| ||||

| ||||

| ||||

| ||||

| ||||

|

References

Acknowledgements

Except for third party materials and otherwise stated below, this content is made available under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike licence (http://creativecommons.org/ licenses/ by-sa/ 3.0/). The material acknowledged below is Proprietary and used under licence for this project, and not subject to the Creative Commons Licence. This means that this material may only be used unadapted within the TESS-India project and not in any subsequent OER versions. This includes the use of the TESS-India, OU and UKAID logos.

Grateful acknowledgement is made to the following sources for permission to reproduce the material in this unit:

Figure 1: © The Open University

Figure 2: cartoon, © unknown.

Every effort has been made to contact copyright owners. If any have been inadvertently overlooked the publishers will be pleased to make the necessary arrangements at the first opportunity.

Video (including video stills): thanks are extended to the teacher educators, headteachers, teachers and students across India who worked with The Open University in the productions.