Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Wednesday, 4 February 2026, 12:25 PM

TI-AIE: Perspective on leadership: leading the school’s self-review

What this unit is about

Imagine a coconut-water vendor drumming the coconuts with the flat of his knife to estimate their age and sweetness, or a shopper in the market smelling the ripeness of fruit. We all regularly make judgements about quality based on data and observations.

In school, teachers and leaders also need to evaluate and make judgements so that they can understand how a school is doing, and how to improve it. However, it is important that these judgements are based on robust evidence.

It is only relatively recently that self-review – a school looking critically and systematically at its own practices – is seen as ‘best practice’ and is being brought into national and state evaluative approaches. Its introduction is based on the recognition that if schools themselves identify the things that they need to get better at, they are much more likely to do something about it.

This unit focuses on supporting school leaders in embedding self-review processes and procedures, so that these can drive school improvement. It will help you to think about what aspects of your school’s work you would like to review, how to collect data and how to report on what you find. The unit Perspectives on leadership: school development plan will focus on using the evidence collected to make a development plan.

Learning Diary

During your work on this unit you will be asked to make notes in your Learning Diary, a book or folder where you collect together your thoughts and plans in one place. Perhaps you have already started one.

You may be working through this unit alone, but you will learn much more if you are able to discuss your learning with another school leader. This could be a colleague with whom you already collaborate, or someone with whom you can build a new relationship. It could be done in an organised way or on a more informal basis. The notes you make in your Learning Diary will be useful for these kinds of meetings, while also mapping your longer-term learning and development.

What school leaders will learn in this unit

- The advantages and challenges of school self-review.

- The nature of school self-review and the self-review cycle.

- How to gather and use qualitative and quantitative data.

1 What a school self-review is, and its advantages and challenges

What do we mean by school self-review? Quite simply, school self-review is about looking at how well a school is doing.

- How well are students learning?

- How well are they performing academically, socially, emotionally and physically?

- How well is the school organised to support students to learn?

- How effective are teachers in their core work of supporting students to learn?

- How well is the timetable organised?

- What role is played by co-curricular activity?

- How effective are relationships with the community?

Many more detailed questions can be asked and form the basis for self-review.

Pause for thought

|

Figure 1 Students learning.

In a self-review, the school leader and the teachers ask themselves the same sorts of questions that an external reviewer would ask. When they discover something that is not as good as they would like it to be (such as attendance being worse this year than last year), they can investigate and do something about it. Doing a ‘self-review’ is about finding out what the school does well and what needs developing before a formal external review takes place.

Understanding how well the school is performing can be time-consuming, but it is a critical element in school leadership. A shopkeeper needs to know what has been sold every day so that they can order the correct amount of stock for the next day. She needs to know what has not been selling well and try to ensure that her staff are working well and honestly, and that there is enough profit to pay them and buy new stock. A shop cannot afford to be inefficient or it will lose money and go out of business. Schools do not have simple profit and loss accounts, but they still need to know if they are doing well.

Case Study 1: Mr Mohanty builds bridges with parents

Mr Mohanty is a newly appointed school leader at a medium-sized rural secondary school with nine teachers.

I was nervous about starting my new job. The school had a poor reputation, as a previous head had misappropriated school funds. My immediate predecessor had only been in the job for a few months and found the distrust in the community difficult to handle. I decided that I needed to do two things: the first was to listen carefully and gather as much information as I could about the school, and the second was to give the teachers some positive feedback as soon as I could. Morale was clearly very low, with teachers leaving at the earliest opportunity every day.

I started by looking at the attendance data and the exam results. Neither were very good, but the maths results were better than the rest, so I spoke to the two maths teachers, congratulated them and asked them about their approach to teaching. I also looked at information about the number of courses that teachers had attended, the records from parents’ evenings (very few parents attended), the punishment book (there were a lot of entries) and the minutes of the school management committee [SMC] meetings.

After a few weeks I had a clear idea about how well the school was performing, the extent of stakeholder involvement, and some evidence about the better aspects of the school. The data I collected provided a basis for my own evaluation, and for discussion and planning. It also gave me some bench marks against which I could measure progress.

Activity 1: Identifying the advantages of self-review

School self-review consists of collecting data, and then analysing that data to work out what the school is doing well and what needs to improve. The self-review will form the basis of a school development plan, which you study further in another School Leadership unit (Perspective on leadership: leading the school development plan).

Re-read the case study and in your Learning Diary, make a list of the advantages of the process of self-review.

Discussion

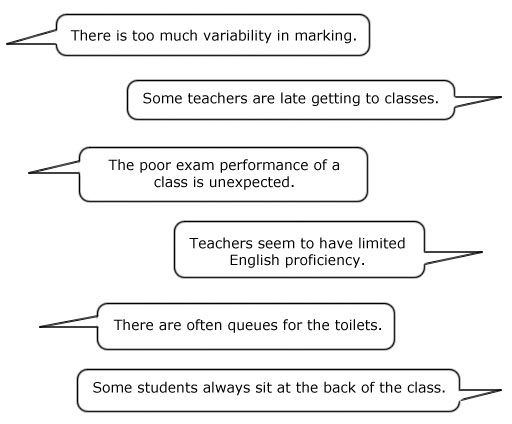

School self-review has to be an objective process. It must be fair and measured, using evidence based on observations and data. It is not about simply collecting information to satisfy legal requirements or to respond to external demands; nor is it about listening to or acting on prejudices, or favouring some stakeholders over others.

Activity 2: True or false?

For each of the following statements, reflect on the extent to which they are true. Are the statements ‘always true’, ‘sometimes true’ or ‘never true’? Note down your thoughts in your Learning Diary.

- School self-review is only for school leaders and stakeholders.

- School self-review tells you everything you need to know about a school.

- School self-review is best carried out in a culture of honesty.

- School self-review is about finding out what is wrong with the school.

- School self-review takes a great deal of time.

- School self-review can help everyone see what needs doing.

- School self-review provides a basis for analysis reflection and planning.

Discussion

Of the above, only statements 3, 6 and 7 are always true. Although a school self-review is led by school leaders, the process can involve anyone. In some schools, students are key players in review – after all, they see more of teaching and school organisation first-hand than anyone else and, when suitably prepared, can play a valuable role.

The review will focus on certain key areas. An annual review may focus on several key areas, or one or two really important ones. The purpose is not to find out about what is wrong, but to enable school leaders to celebrate the schools’ successes and identify areas for development. It is important that it is not conducted in an atmosphere of attributing blame.

Done properly, a school review is part of the daily work of the school leaders. Much of the data will be collected routinely. The analysis is both interesting and informative, and enables them to focus their energy on the areas that will make the greatest difference. It takes time, but it will ultimately make the school leader’s job easier.

Activity 3: Identifying the challenges and opportunities

Consider the following two scenarios and note down your responses to the questions in your Learning Diary.

- Imagine you have just taken over as the leader of a newly established school that has only been open for a year. You will need to find out about your new school before you can make a plan about how to make improvements. What challenges do you think you will face and what opportunities does a review present?

- Imagine you have been the school leader for ten years in the same school. The District Education Officer has called a meeting of all the local school leaders to explain that they want you to carry out a review of your school and report back in six months’ time, along with an action plan. What challenges do you think you will face and what opportunities does the review present?

Discussion

As a new school leader, teachers will be anxious to impress you, so collecting accurate data might be difficult. Some teachers might be suspicious of your motives; some will be worried that you are going to blame them for things that are wrong with the school. It will be important to make sure that you start by focusing on something that you think the school does well.

As an established school leader, any new behaviour on your part might be treated suspiciously. You will need to emphasise that this will be a team effort and that you need their help. Make sure that you start by collecting data on something that is going well. The public celebration of success will give people confidence and make it easier for you to tackle issues that are problematic.

The process of self-review needs to be managed well, so that stakeholders are clear about the process and the purpose. They are then more likely to contribute to the process in a considered and constructive way. The process needs to be positive and open – it is not about finding out what is wrong and attaching blame. The process should also be realistic and focused in terms of what is reviewed and how much time is spent gathering information that will make a difference to outcomes for students.

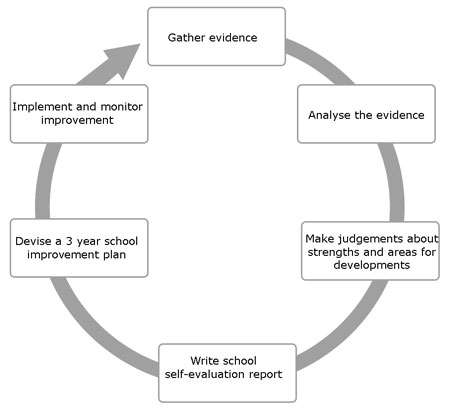

Self-review is part of a cycle of improvement activity that is summarised in Figure 2. You will see that there are different stages that all feed into a cycle of review and change. There are other leadership units that address planning and implementing change which may be useful for you to look at next.

Figure 2 The self-review cycle (adapted from Professional Development Service for Teachers, undated).

The rest of this unit will focus on how to gather evidence, how to organise it and how to present it on a self-review form.

2 Data and information

A school self-review is most effective when it is integrated into existing systems and carried out as part of an ongoing process rather than as a separate activity. It may take time to set all this up in your school. As a starting point, you need to start to gather evidence or data on a regular basis (Stage 1 in Figure 2). Data can generally be separated into two types:

- quantitative – numerical data

- qualitative – data collected through techniques such as attitudinal questionnaires, observations and stakeholder interviews.

Quantitative data is generally easier to deal with, since it is indisputable. For example, the following are statements of fact:

- the percentage of students who gained above 80 per cent in Class X examinations

- the attendance level of female students in the year

- the number of staff meetings that were held

- the proportion of parents who attended a meeting.

Qualitative data is quite different in nature, and is more about opinion:

- feedback on new textbooks

- opinions about how best to teach multigrade classes

- what makes students feel safe at school.

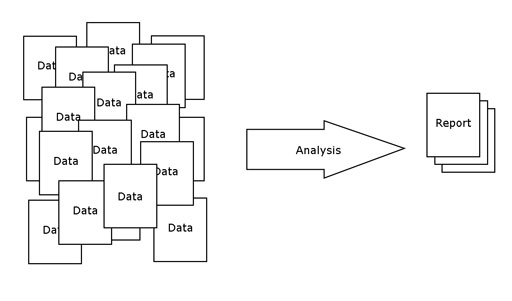

For comprehensive school self-evaluation there is likely to be a mix of quantitative and qualitative data gathered, but it is only when this is analysed to identify patterns or draw conclusions that this data becomes useful information.

Figure 3 Data needs to be analysed to be useful.

Activity 4: Sources of evidence

A school self-review should start by thinking about the sorts of questions you wish to ask, what data you have, and what data you will need to collect.

Work with your deputy and other senior colleagues (or if you are the leader of a small school with less than five teachers, involve everyone) to complete the school data matrix in Resource 1.

- For each question, identify a possible source of data and how it could be collected.

- Think about how you could analyse that data to find out as much as possible about your school. (For example, attendance and achievement data can be analysed to see how male and female students perform.)

- Add some more questions that you would like to investigate in your school.

Discussion

It is likely that you will have more quantitative than qualitative data to start with. This is likely to cover examination results, attendance, health and safety meetings, and so on. You may have little data on what stakeholders think about aspects of school life and especially what happens in the classroom, so this will be covered later.

Case Study 2: Ms Mehta gathers evidence to check her intuition

Ms Mehta is the school leader of an increasingly successful rural middle and upper secondary school. As she was checking attendance data to send off to the district, she noticed a pattern emerging of the seasonal non-attendance of her female students in the middle school. It interested her enough to investigate further. What she discovered was that their attendance dipped dramatically during the planting and harvesting seasons. Her instinct was that this was linked to their mothers being needed in the fields and the elder daughters acting as mother to their younger brothers and sisters.

This initial review told Ms Mehta that she needed more evidence before she could be certain about the cause of the absences. With the support of her management committee she sought to get more information. She did three things:

- She carried out an informal survey of her female students in Class VI–VIII of those students with seasonal absence and those who consistently attended.

- She asked teachers who lived in the locality to make some home visits to interview the mothers.

- She created a new set of statistics, matching a sample of attendance of female students with exam results in Class X. She was interested to know what the pattern looked like. Unfortunately, she did not have a soft copy of the attendance-only paper records, so she got the support of one of her young, motivated teachers and her administrative assistant to collate and analyse (or crunch!) the numbers.

Ms Mehta found that there was a direct link (or correlation) between female students’ absences in the middle school with (a) drop-out at Class VIII, and (b) lower performance at Class X board examinations. This led to a target for the coming year to identify a strategy through the SMC to either reduce seasonal absenteeism or to find ways of supporting those students who are unavoidably absent to continue their studies.

Case Study 2 shows how data can be the catalyst for further investigation of any aspect of your school’s performance. In this case the review started with quantitative information that showed an issue (Stage 1 in Figure 2). Analysis (Stage 2) revealed a problem; this led to additional information-gathering to provide a deeper understanding of the issue and helped the school leader to organise a plan. In other cases you might start with qualitative information and then gather more quantitative information to provide a complete picture. In Ms Mehta’s case, she made a link between the low attendance of female students and their performance in exams.

When gathering data, it is important to ask: ‘So what?’ What is the impact on students’ academic, social, emotional and physical progress? Gathering data is of little value unless it is analysed and plans are made to build on emerging strengths and address areas for improvement (Stages 2 and 3 in Figure 2).

If you open up the discussion, your teachers and parents may suggest all sorts of sources of information for a school self-review that can span all aspects of school activity, such as:

The initial steps for the school to take once it has identified a potential issue – regardless of what it is – should include:

- deciding whether or not this is an issue that needs to be addressed

- identifying the team that needs to lead the evidence collection – in Case Study 2, Ms Mehta’s team included parents, members of the school board and local teachers

- identifying the evidence that needs to be collected

- evaluating the evidence to determine what the problem really is and how to address it.

Figure 4 Interpreting a report.

Gathering data is the starting point for your self-review. You then need to analyse the evidence (Stage 2 in Figure 2) and make judgements (Stage 3) about the strengths and areas for improvement. A common criticism of school self-review is that it can be too descriptive and insufficiently evaluative – school leaders merely describe what is happening without asking what they can learn from it.

In the case study, Ms Mehta didn’t just accept the data – she formed a hypothesis that she checked by collecting more data. In research terms, she ‘triangulated’ her data. Once she was sure that she really understood the reasons for the fall in attendance and had demonstrated the link between this and exam performance, she was able to take action.

Case Study 3: What is behind lateness?

School leader Mrs Agarwal overheard a conversation in the staffroom between the Class VI and Class VII teachers. Both were feeling frustrated because they felt that punctuality in their classes was getting worse. Mrs Agarwal asked them how they knew and they said it was just a feeling.

‘Is it the same students every day?’ she asked. They weren’t sure.

Mrs Agarwal promised to help them tackle the problem. She asked them to keep detailed records for two weeks of who was late and who was on time. She suggested that the teachers asked the students to keep their own records, as this might help them to take responsibility for making sure that they arrive on time.

After three weeks, the three of them sat down in order to analyse the data. They noticed that the students who lived in a certain part of town were late on Mondays and Fridays, and those who lived in a particular village were late on Wednesdays.

Activity 5: How the data leads to next steps

If you were Mrs Agarwal, what would you do next? You have data on attendance and have analysed it to see that there are patterns of attendance relating to where the students live. What are the possible reasons for this? In your Learning Diary, make a list of the questions you would ask and the data you would collect in order to understand what is happening and why.

Discussion

Remember that you would be doing this activity with these two teachers so that you can share the responsibility for asking questions and collecting data. You will probably have noted that you need to talk to students and their parents to get more data and maybe find out what transport they use to get to school. There may be factors such as market days or religious observance that affect attendance, so you need to allow yourself to be surprised about what data you uncover and not narrow your questions to only check out your own hypothesis. If Mrs Agarwal suspects that the poor attendance is solely due to family responsibilities, she may not enquire enough about road conditions or the logistics of getting to school on those days.

Collecting data and information can be used to solve specific problems, but more importantly, it can provide you with an overview of how your school is doing. This is Stage 4 in the evaluation cycle shown in Figure 1.

As you develop the habit of collecting data, you will be able to look at trends over time as well as achievement or attendance in a particular year. By breaking down the data, you can reveal what it is actually telling you. This might be, for example, that female students’ attendance in Class I–IV is almost 20 per cent higher than in Class V–VIII, or that attendance drops by almost 35 per cent at harvest time.

3 Organising your data

All schools will be concerned about the same things: student attendance, student achievement, behaviour, parental involvement, etc. It is therefore helpful to develop a template that presents an annual review of the key issues in your school. The headings will help you develop a routine for collecting data.

Resource 2 provides a starting point that you are going to develop in Activity 6. The self-review form is divided into key areas, and within each area there is a space to summarise what you have found out (your analysis) and a space to list the evidence you have gathered. This is important because other people who might be interested in your self-review (such as the district education officer or members of the SMC) will need to be confident that your analysis is based on clear evidence.

Activity 6: Developing a self-review form

Look at Resource 2 and check that the categories fit your context and priorities.

Make a list of the evidence that you will need in order to complete each section. This can include quantitative data, observational data or survey and interview data.

Case Study 4: Ms Chadha’s self-review form

The SMC at Ms Chadha’s primary school was keen to know how ethics and morals were being promoted in the school, and how effective this was. As school leader, Ms Chadha started to identify on a self-review form what she was going to review (Table 1). She wrote these different focus areas in the column on the left. In the right-hand column, she listed the evidence that she was using to review each focus area. Notice how the evidence is a mixture of quantitative data, survey data and observational data. Ethics and moral education is clearly going well at this school.

| Focus areas for reviewing ‘how far ethics and morals are promoted in the school’ | Sources of evidence for review |

|---|---|

| We promote good, respectful relationships between students and teachers. Relationships in the school are good: there is very little bullying and students feel safe. We have introduced a new behaviour policy, with students taking responsibility for their own behaviour. |

|

| We collectively celebrate festivals and the work of individuals who have made a contribution to society. At least one day each half-term is off-timetable with specific activities to raise students’ awareness of moral and ethical issues. |

|

| We went out into the community to support disadvantaged groups, and invited members of the community to talk to students about their work. |

|

Once the self-review form is complete, it will form the basis for the school development plan (Stage 5 in Figure 2) – you may want to study the Perspective on leadership: leading the school development plan unit related to this next.

You should aim to organise the regular collection of data (Stage 6) so that:

- the cycle of improvement is continual

- data becomes readily accessible nad decisions are made on the basis of evidence.

In the final section of this unit the focus will be on five tools for self-review.

4 Tools for self-review

There are many tools for self-review; in this section you will be introduced to five tools that can help you to collect data and successfully engage others in reviewing what happens in your school.

Tool 1: Learning walk

Figure 5 A school leader taking a learning walk.

A learning walk is when school leaders walk around their school during the school day to learn about what is going on. Good leaders have always done this. It is an essential element of self-review because it provides the opportunity to do the following:

- Pause and reflect on what you are seeing. You will need to determine the style you adopt. The less visible you are, the more you are likely to see and hear. However, if staff and students think that you are‘spying’, then the approach could become counterproductive. When a culture of support and challenge has been established, staff and students are more likely to be open and honest with leaders.

- Find things out. You can use break times or the start and end of the school day to talk to (and, just as importantly, listen to)the teachers, students, parents and support staff.

- Signal to the teachers that as a leader you are interested in what is going on inside the classroom.

- Focus on a particular issue.

Do not conduct a learning walk at the same time every day, as this will limit the information you find.

Activity 7: Making time for your learning walk

- Sit down (ideally with a trusted colleague) to plan some daily learning walks next week in your Learning Diary. Work out how you can reduce your workload so that you have time to spend an hour a day doing a learning walk, ideally in two half-hour slots. When you are doing this, ask yourself the following questions about how you might make time to do learning walks:

- What is fixed that I must I do? (For example, teaching my own lesson.)

- How can I organise my time effectively? (For example, choose one time of the day, usually in the morning, when you will make all your work phone calls.)

- Is there anything that should or could be done by someone else just as well?

- Is there something that will not a cause a problem if it is delayed?

- Is there anything that in reality doesn’t need to be done at all?

- Plan your week so that you can do walks at a range of times, such as at the start or end of the school day (to interact with parents), in transition times between lessons (when teachers handover to each other in the classroom), at break times or lunchtimes, as well as during teaching time.

- Get a small notepad to record your observations and you are ready to go. Choose a focus for each walk, such as levels of student engagement. This will help you to collect data systematically.

- Now take your learning walks. Record what you see and hear. If you see something that impresses you, then praise the individual or group. The only rule is to be positive and respectful. If your school is not used to you being out and about like this, staff will need reassurance.

- Summarise your findings and look for emerging trends as you do more walking in your school.

- Look to see if you need evidence from any other sources to support what you are finding through the learning walk.

- Start to think about how you can improve any areas and how you will share your findings.

Discussion

A learning walk has many advantages and keeps the leader in contact with what is happening in the classrooms – the heart of school life. It need not take long. In schools where school self-review is well-established, a learning walk may be undertaken by a team of people and will probably look at one specific aspect of practice, such as the types of questioning used by the teachers, the start or end of lessons, the learning of students with difficulties, and so on.

Tool 2: Book look

A book look is a formal activity where you collect books from specific cohorts of students for monitoring and evaluation purposes. It fulfils a number of functions, including helping you to:

- gauge the nature and quality of work set by the teacher

- analyse rates of completion in the class

- identify how far and how well teachers correct and mark work

- look at the quality of the content and presentation

- assess the quality of the learning

- find indications of the types of activity being undertaken in lessons.

To look at all the books would take too much time, so you need to develop a way of sampling. For example, you may look at:

- every third notebook

- the work of two male and two female students from each class

- a sample of books from students in different classes in a single subject.

Tool 3: The collection and analysis of quantitative data

Collecting evidence can be challenging. In very good schools it is a habitual activity. The big thing you have to do is decide what you focus on and how this will help improve your school’s performance. As the school leader, you need to keep the focus of self-review on improving the learning outcomes.

Activity 8: Using data from end-of-year tests

Following your end-of-year tests, study the results data to extract evidence that might help you make some improvements. If the data you need is not readily to hand, then you will know that you need to collect and record it differently next year so that this task is easier next time.

Look at the tests of a particular class by subject and, if one does not already exist, create a matrix so that you can check the performance by counting students who get results in each percentile (10 per cent – see Resource 3). When you have plotted this data, you need to analyse it to turn it into useful information and to guide you about what else you might need to find out. Note down your thoughts in your Learning Diary.

- Look across the data to see whether there is one subject where student performance significantly differs from their other subjects. Then look at the staff teaching the subject. Are the staff performing well or are improvements needed?

- Look at the data for individual subjects where there is more than one teacher teaching the same subject. Is there a teacher whose scores are markedly different? Is it maybe because they need support or are performing significantly better?

- Use the evidence from the data to check out why there are these discrepancies, praising those who should take credit and taking action where there are issues that can be addressed.

Discussion

Were you surprised by the data once it had been collated in this way? Did it give you ideas about what further investigations you might need to make? Be cautious about making immediate conclusions from your data – it may be that there are other explanations that you have not thought of (such as attendance or classroom size) that are impacting on the learning outcomes. You may need to collect further evidence through observation and conversations.

Once you start analysing data like this, you will think of other ways that you can collate and use the data – including tracking individual students or groups of students so you can identify any difficulties they may be having.

Tool 4: Conversations with stakeholders

As school leader you need to check the views, attitudes and experience of various stakeholders. This does not need to be an overbearing duty. If you are undertaking your learning walks, then you will be able to talk with parents at least once a week at the start and end of the school day. During breaks you can sit down with individuals or small groups on issues that you have a concern about or an interest in. You can have regular agenda items for your staff meetings around school improvement targets and their perceptions.

In the case of your primary stakeholders, the students, self-review is a two-way process. It is important for you to get first-hand experience of what the life of a learner in your school is really like and the level of support and challenges they experience. Students have a lot to offer to the self-review process, but they need ‘training’ and support if they are to be confident in voicing any critical views. Staff may initially be mistrustful if you give credibility to the views of students that conflict with their own. Again, it is about building a positive and open culture. In some schools, students will have regular councils or parliaments, and may be involved in making decisions about issues that affect the school community.

Parents and guardians are also key stakeholders who can help with a school review. You need to make time to talk to them and give them the opportunity to hear their views.

Activity 9: Shadowing students

Of all the data collection exercises that a school leader can do, student shadowing is the most immediately illuminating. By observing a single student across a whole day, you can get a great deal of information about:

- style(s) of teaching

- levels of student engagement

- teacher–student relationships

- use of time and resources

- the impact of teaching on learning.

Ideally, you could do this shadowing – but because of your position of power, this could be quite intimidating for the student. Think about whether you could delegate this task to a member of the SMC or to a trusted teacher. You need to be careful about the choice of student – if you deliberately choose your most able student, you are likely to get a different picture than by observing a student with more complex learning needs. You will also need to make time to discuss the experience with the student afterwards, because their views of the day are also important.

Following the shadowing, you need to analyse what you have seen and share the key learning points with the staff and maybe the SMC.

Discussion

You will need to devote uninterrupted time to this task, and must emphasise to teachers that you are looking at learning, not teaching. It is very difficult for you to be a ‘fly on the wall’ in your school and the students may well be unnerved with you trailing around behind them. You need to think carefully about how not to be obtrusive and disruptive in this role – telling students and staff beforehand what you are doing is essential, but it is best to keep the name of the student you will be shadowing a secret until the day itself.

Tool 5: Classroom observation

Classroom observation is initially difficult to carry out in a non-threatening manner, especially because you are the school leader and so people will behave differently if you are in the room. You may be accustomed to students jumping to attention when you enter the room, but ideally you will want to slide into the classroom quietly and stand or sit where you can observe the whole room – if you sit at the back with the students, you will be closest to their experience in the classroom. You may move around the classroom if the students are working in groups or on individual work in order to sample their learning.

If there is no culture of observation in the school, you will need to start slowly. It could be sometime before you are able to observe lessons without causing anxiety. Here is one possible approach:

- Encourage your teachers to observe each other. A number of activities in the TESS-India units encourage this. While they observe each other, you could offer to teach their class. In this way, students will get more used to seeing you in the classroom.

- Take regular learning walks so that teachers and students get used to seeing you outside the classroom, or lingering by the doorway, during lessons.

- When you feel able to observe lessons, use an observation form so that the teachers know what you are looking for and use this to discuss the lesson with them afterwards. Resource 4 has an example that you could use.

5 Summary

This unit has taken you through the self-review cycle and has introduced you to some tools that you could use to collect evidence and review your school.

Collecting evidence in an organised manner about key aspects of the school’s performance will help you to adjust your actions and plans appropriately. This can be a task that is shared, but at the start is likely to need strong leadership and building a culture of trust. As schools become more autonomous, this goes hand-in-hand with accountability; school self-review offers an objective process that provides suitable evidence to celebrate strengths and address weaknesses. A detailed self-review means that a school can be confident in its planning and prioritising so that is becomes effective and improves year-on-year.

This unit is part of the set or family of units that relate to the key area of perspective on leadership (aligned to the National College of School Leadership). You may find it useful to look next at other units in this set to build your knowledge and skills:

- Building a shared vision for your school

- Leading the school development plan

- Using data on diversity to improve your school

- Planning and leading change in your school

- Implementing change in your school.

Resources

Resource 1: School data matrix

| No. | Question | How can data be collected? | Do we already collect this data? | How can the data be used for school improvement? |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Example | How good is attendance in our school? | Register daily | Yes | Identifying attendance patterns, Targeting poor attendees |

| 1 | How do students achieve in our school? | Exam results | Yes | How each class is doing, how different groups are doing, for example male and female students. |

| 2 | Do students make good progress in our school? | |||

| 3 | Is behaviour good in our school? | |||

| 4 | Do students feel safe in school? | Survey of students | No | |

| 5 | Is there a positive learning environment in our school? | |||

| 6 | Are the buildings in good condition? | |||

| 7 | Do students do their homework in our school? | |||

| 8 | Are parents satisfied with our school? |

Resource 2: Example school self-review template

| Section | Evidence |

|---|---|

| Achievement of students at the school: How are students achieving? | |

| Quality of teaching and learning in the school | |

| Behaviour and safety of students in the school | |

| Quality of leadership and management in the school | |

| Breadth of the curriculum in the school | |

| Links with the community |

Resource 3: Distribution of exam scores in one class per subject

Enter the number of students falling into each percentile on the grid (Table R3.1), allowing you to see patterns of achievement and any disparities between subjects in the same cohort.

You could use this same grid with different classes or teachers rather than subjects in the first column if you wanted to gather other comparative data.

| Subject | Percentile | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0–9 | 10–19 | 20–29 | 30–39 | 40–49 | 50–59 | 60–69 | 70–79 | 80–89 | 90–100 | |

| Maths | ||||||||||

| English | ||||||||||

| Science | ||||||||||

| ICT | ||||||||||

| Sports | ||||||||||

Resource 4: Lesson observation

| Student teacher’s name | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Date | Time | Duration | |||||

| Class | Average age | No. of male students | No. of female students | ||||

| Subject | |||||||

| Topic | |||||||

| Sub-topic | |||||||

| Notes on the lesson plan |

|

||||||

| Notes on the learning objectives |

|

||||||

| Notes on the instructional materials |

|

||||||

| Notes on the use of previous knowledge and entry behaviour |

|

||||||

References

Acknowledgements

Except for third party materials and otherwise stated below, this content is made available under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike licence (http://creativecommons.org/ licenses/ by-sa/ 3.0/). The material acknowledged below is Proprietary and used under licence for this project, and not subject to the Creative Commons Licence. This means that this material may only be used unadapted within the TESS-India project and not in any subsequent OER versions. This includes the use of the TESS-India, OU and UKAID logos.

Every effort has been made to contact copyright owners. If any have been inadvertently overlooked the publishers will be pleased to make the necessary arrangements at the first opportunity.

Video (including video stills): thanks are extended to the teacher educators, headteachers, teachers and students across India who worked with The Open University in the productions.