Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Friday, 27 February 2026, 9:22 PM

TI-AIE: Perspective on leadership: leading the school development plan

What this unit is about

This is the second of two units that promote school improvement. It follows on from the unit Perspective on leadership: leading school self-review. This unit focuses on the process of school development planning – Stages 5 and 6 of the school improvement cycle (Figure 1). Once a review has been carried out, the school leader and the school management committee (SMC) will be aware of what the school is doing well and what areas need to be developed. You and your leadership team – be it one other teacher in a very small school, or a group of four or five senior teachers in a large school – are in a position to make a plan to achieve those improvements. This unit will take you through the planning process and help you to develop a template for your plan.

Figure 1 The self-review cycle (adapted from Professional Development Service for Teachers, undated).

Learning Diary

During your work on this unit you will be asked to make notes in your Learning Diary, a book or folder where you collect together your thoughts and plans in one place. Perhaps you have already started one.

You may be working through this unit alone, but you will learn much more if you are able to discuss your learning with another school leader. This could be a colleague with whom you already collaborate, or someone with whom you can build a new relationship. It could be done in an organised way or on a more informal basis. The notes you make in your Learning Diary will be useful for these kinds of meetings, while also mapping your longer-term learning and development.

What school leaders will learn in this unit

- The main features of an effective school planning process.

- To plan for school-wide improvements in student learning.

- To engage stakeholders and especially the SMC in school development planning.

- To write an effective school development plan that makes a difference to outcomes for students.

1 Introducing the school development plan

Figure 2 The school development plan is a road map that sets out the changes a school needs to make to improve.

A school development plan (SDP) provides the basis for school improvement and should reflect the school’s philosophy and vision. It lists the priorities and actions for the next period of time – many schools make a general three-year plan that is supplemented by a more detailed yearly plan.

The SDP drives the next school self-review and demonstrates to the community that the school is working to achieve the best possible outcomes for its students. The first case study and activity illustrate why planning is important.

Case Study 1: Why development planning is important

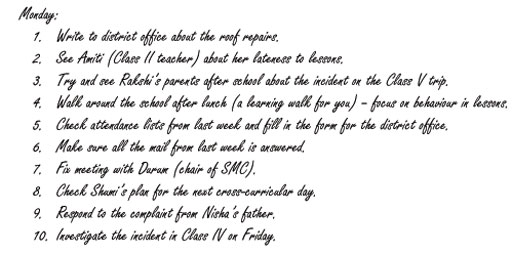

Mrs Nagaraju is a school leader in an urban primary school. Like most school leaders she is very busy and has a ‘to do’ list each day to make sure she remembers what she needs to get done:

Each day Mrs Nagaraju has a similar list. Most of what she has to do is respond to issues that have arisen and complete the necessary administration.

Activity 1: Why plan?

Look at Mrs Nagaraju’s list for Monday.

- Which items on the list are essential administration?

- Which items on the list are responses to events?

- Which items on the list are actions that could lead to improvements in teaching and learning?

- If she is very busy, which items are likely to be left undone?

Write in your Learning Diary the advice that you would give to Mrs Nagaraju to help her manage her tasks.

Discussion

You will have realised that eight out of ten items are essential administration or responses to events. Only two items – taking a learning walk (item 4) and checking the plans for the next cross-curricular day (item 8) – are things that have the potential to impact directly on students’ learning. The learning walk will enable her to gather information about learning behaviour, so that she is better able to support her teachers; ensuring the plans for the cross-curricular day are going well will help to make sure that the students have a positive experience. Items 4 and 8 are non-urgent, so could easily get ignored. But if Mrs Nagaraju is to make a difference to teaching and learning in her school, these items should have a high priority. Maybe there are some administrative tasks that she could delegate to someone else? Maybe the class teachers could take responsibility for items 5 and 9?

As a school leader, it is easy to be swamped by everyday events and administration. It is sometimes difficult to find the time to focus on bigger issues and solve complex problems. The purpose of the SDP is to help you be strategic, and to prioritise and identify actions that will ultimately lead to improvements in teaching and learning. The same will apply to other busy teachers in the school. The development plan will help all of you to remain focused on longer-term goals and prioritise tasks that will help you to achieve those goals.

Having carried out a review of the school, you and your leadership team (or fellow teachers) will have identified things that you need to do in order to improve your school. These could include:

- increasing the number of students who can read fluently by the end of primary school

- changing the structure of the school day

- improving the use of continuous and comprehensive evaluation (CCE) in the school.

The first step is to identify some priority areas. This will involve talking to stakeholders, and the priorities chosen should be consistent with your collective vision for the school. (The unit Perspective on leadership: building a shared vision for your school is also useful in combination with this unit).

Once you have a vision and priorities, the next step is to devise set of actions that are likely to bring about the desired change. For example, if the agreed priority is to change the structure of the school day, actions could involve:

- identifying two or three options for an alternative school day schedule

- consultingteachers, students and parents to identify the option that is likely to be the most appropriate

- rewriting the timetable to fit the preferred option and then presenting it for approval to staff and parents

- communicating the plan to students and deciding the date from which the new day will start.

You should identify someone to take responsibility for each action, a timescale for completion and some criteria that you can use in order to monitor progress. Activity 2 will help you to be specific. It is easy to write down things like ‘improve attendance among the female students’, but nothing will happen unless someone takes specific action.

Figure 3 Aims need actions.

Activity 2: Converting aims into actions

Consider the aim ‘To improve the attendance of female students in my school’. Write down in your Learning Diary four of five actions that would lead to achieving this aim.

Resource 1 sets out a template for an SDP. This will be considered in more detail later in the unit, but have a look at it now so that you know what you are aiming for.

The first step is to identify the priorities for the school (the first column of the table). The self-review will have provided plenty of ideas, but these will need to be discussed with your stakeholders.

2 Working with stakeholders

The SDP is the principle tool for planning ongoing school improvement. It is now part of educational legislation and is a central element in the government’s approach to decentralising decision making to schools through the Right to Education Act 2009 (RtE). The Act states:

The school management committee shall perform the following functions, namely:—

- a.Monitor the working of the school;

- b.Prepare and recommend the School Development Programme;

- c.Monitor the utilisation of the grants received from the appropriate government or local authority or any other sources;

- d.Perform such other functions as may be prescribed.

The RtE 2009 has made schools and their SMCs more accountable and ensures that they, rather than a distant education office, take responsibility for the quality of learning in their school. Decentralisation also helps in the ‘creation of spaces where local-level representative institutions can work closely with teachers to enhance efficiency as well as co-operation between decision-making bodies’ (NCERT, 2005).

Under the RTE 2009, every school must establish a school development committee that can act as an executive body of the SDP. The committee should comprise school administration, teaching and non-teaching staff, and community members.

An SDP should be an agreed, shared document. It will be developed mainly by the school leader and the teachers, but valuable insights will be provided by parents, community and students. The final document needs to be agreed by the SMC (primarily) or the SMDC (secondarily).The key stakeholders are you and your staff, the SMC, parents, and students.

Working with the SMC

The key to developing an effective relationship between the SMC and the school is that of partnership. The relationship is interdependent and, as the school leader, you need to build a strong relationship with your SMC. To do this, you could:

- communicate regularly so that they feel part of the community

- invite them into school in order to celebrate successes

- listen carefully to their advice

- use their expertise to enhance the curriculum.

Figure 4 An SMC meeting.

Activity 3: An enthusiastic or domineering chair

In an SMC the key is to establish trust and an atmosphere of openness and honesty. However, one challenge that a school leader can face is an enthusiastic or domineering chair who wants to exert their power and influence.

Think about what you would do in the scenario below and record your findings in your Learning Diary.

The SMC’s new chair is very enthusiastic and has already had a number of meetings with stakeholders and some staff. He is committed to more extra-curricular activity and has, as a result, drawn up a detailed plan that he wants you to approve. How do you respond?

Discussion

On the positive side, you want to recognise the chair’s enthusiasm and commitment, and be positive about improving extra-curricular activities.

However, you need better teamwork and communication with the chair so that activities are not undertaken in isolation and possibly in conflicting ways. You will have information and a view on extra-curricular activities, and would want to make sure that any consultation is based on a considered approach – not just talking to some people who may not be representative of their groups.

This is where having an SDP in place is helpful. You should draw the attention of the chair to the plan, highlighting any sections on extra-curricular activities and examining the overlap with his plan. If this is not something that is in the plan (because there are already activities going on that he may not know about), explain the school improvement cycle and invite him to carry out a review of extra-curricular activities.

Neither the school leader nor the SMC chair should be drawing up plans alone – all new initiatives should be considered in the context of the collective vision, the self-review and the agreed development plan.

Working with your staff

You and your staff will be responsible for carrying out the actions identified in the SDP. From your point of view, delegation will be important, but you need to make sure that your teachers are involved in the development planning process. Case Study 2 shows what happened to Mr Shah when he ignored the concerns of one of his teachers.

Case Study 2: Mr Shah learns the hard way

Mr Shah is school leader of a school with Classes VIII–X. He attends the SMC meeting.

I was nervous about the SMC meeting because we were due to discuss the SDP. The rest of the staff and I were excited by the plan as we had some quite radical items. In particular, we had agreed that twice a term, we would have a day off from the timetable and organise a cross-curricular day. This would enable students to undertake extended projects and to study important environmental and social issues that cut across subject boundaries. Most of the textbooks have chapters at the back of the book on these sorts of issues and there is considerable overlap between subjects. We were convinced that we would be able to save a considerable amount of time.

When we came to that part of the plan, three of the parent representatives expressed serious concerns and argued that we should be concentrating on the main subjects. Halfway through the meeting, it occurred to me that two of them had children in Mr Rawool’s class. Mr Rawool is a science teacher and had been opposed to this change. Thinking back to the staff meeting, I remembered that he had been shouted down by some enthusiastic teachers and after that had been very quiet. I suspect that he had been talking to the parents and was using them as a way to disrupt the plan.

It was a very difficult meeting and in the end I had to agree to make a more detailed plan about how the cross-curricular days would work, demonstrating explicitly to the committee how they would support learning. I resolved to get Mr Rawool to help me to do that.

The whole incident made me realise that people who feel marginalised and ignored can be quite disruptive. I should have made sure that Mr Rawool’s concerns were taken seriously in the staff meeting and I should certainly have spoken to him afterwards and tried to get him on board straight away.

As a school leader you will be holding regular staff meetings. One of the challenges is to make time to discuss issues rather than carry out administration. One approach that you could use is to plan the agendas well in advance, based on the timescales in the SDP.

Working with parents

Parents are a real asset in any school if you can harness their support. The SDP will be carried out by you and your teachers, but be prepared to involve parents in the process of self-review and discussions about priorities.

Of course power, wherever it is held, can be open to misuse. Political issues can intrude into school and some parents may be seeking to push issues that are relevant to them personally and may not be in the best interests of the wider group. In some communities, parental groups can be more concerned with keeping things as they are rather than improvement. The school leader must be alert to all such issues and should use leadership skills to find the best way to work productively with the local community and its chosen representatives.

Case Study 3: Mr Meganathan meets the SMC

Mr Meganathan is the school leader of a small secondary school. The SMC had five parent representatives. He describes a meeting with the SMC.

I run quite a progressive school. We have two well-qualified science and maths teachers. Last year we took the decision to actively encourage more female students to study science and engineering. We decided to give all the female students in Class VIII the chance to study woodwork and the male students the chance to learn to cook and mend their clothes. The female students enjoyed woodwork and we are hoping that it will encourage them to take an interest in using their creativity to build useful things.

There were a number of new faces at the SMC meeting because there had just been an election for five new parent representatives. I was surprised to find an item on the agenda had been added by the chair: ‘Craft subjects’. When we got to that item, one of the new parent representatives explained that in his view, it not appropriate for female students to study woodwork or engineering, and that male students did not need to learn to cook or sew. He proposed that the curriculum was changed so that students were segregated for craft subjects.

There was a very heated discussion, with an alarming amount of support for the motion. It appeared that some of the people who had original supported the plan were changing their mind. I was very concerned. Eventually, I was able to use a procedural excuse; the item had not been on the official agenda and it should have been accompanied by a paper setting out the arguments so that committee members had the opportunity to see them in advance. The chair agreed that it would be discussed at the next meeting.

During the next few weeks I organised an open evening in which the Class VIII students showed off their skills and talked to the visitors about why they enjoyed woodwork (female students) and cookery and sewing (male students). We made displays of the things they had made in the foyer alongside photographs taken in the lessons. I invited parents into school to observe the lessons. My campaign was successful and at the next meeting, sufficient members of the committee voted against the motion.

Pause for thought

|

As with the SMC, communication is key. Keeping parents informed about what is going on in school will enable you to harness their energy and enthusiasm, and will make sure that they understand your aims and priorities.

Students’ contribution to the SDP

Students can offer much insight into most aspects of school life, but especially the process of teaching and learning. Involving students in the self-review may be an entirely new concept to both them and your staff. However, their opinions will enhance the quality of the SDP that emerges. You can do this by talking to them as you walk around school and by conducting formal surveys about aspects of school life.

As you develop more participatory approaches to learning, the relationships between teachers and students in your school will become more democratic. (For more on this, and depending on which level of school you teach at, see the units Transforming teaching-learning process: leading improvements in teaching and learning in the elementary school or Transforming teaching-learning process: leading improvements in teaching and learning in the secondary school.) Students will have the confidence to express their views and you might want to consider establishing a ‘student council’ to provide a forum for students to discuss aspects of school life (Student Council Support, undated).

3 Writing and monitoring the SDP

The general guidelines for a SDP are given below (American India Foundation, 2011, p. 43):

- There should be an SDP in each school.

- The SDP will be prepared by a sub-committee of the SMC.

- A three-year plan, along with a detailed annual work plan, should be prepared.

- The plan should be send to a designated authority as prescribed by the state authority, through proper channel well in advance to get included in cluster, block and finally the district plans, before it is submitted to MHRD, Government of India.

- The plan must have components that may not require funds, and activities that can be completed with community help should be included.

Figure 5 A successful SDP requires collaboration.

The SDP is a public document, so make sure that you do not set unrealistic targets and that you identify actions that can easily be carried out. The template provided in Resource 1 should help in this respect, as it encourages you to break each aspiration down into manageable chunks. The main sections of the plan are in columns one to six of the template, as listed below:

- The main priority areas: These should reflect the collective vision for the school and need to be agreed by the staff and the SMC. The self-review documentation will provide evidence to inform these discussions. You are unlikely to be able to achieve everything you want to – hence the importance of having a clear vision so that you can identify the priorities together.

- Actions:This column will need to be completed by you and your teachers. How you do this will depend on the issue and on your style of leadership. For some issues, it might be helpful if your teachers identify appropriate actions so that they own them. For others, it will be appropriate for you to identify the actions and present them for approval.

- Who will take responsibility for completing that action: This will need to be negotiated with the people concerned.

- Timescale for the action: This will help to emphasise that the individual named in column 3 is accountable. Any delays will need to be explained to the SMC.

- Resources that will be required: If these are not available, the success of the plan will be at risk. Resources need to be identified at the earliest possible stage so that work can start in order to get outside help if necessary.

- A basis for monitoring the plan:This encourages you to think about how you will be able to ensure that the actions have taken place and that the plan is working. The activities identified in this column will also inform the next round of self-review.

Once the plan has been completed and agreed by the SMC, you will need to report on progress on a regular basis.

Of course, it is not the plan that is the most important thing, but the process. The plan provides the basis for many structured conversations about what you and your teachers are doing and why. It ensures that all members of the community are working together. If someone wants to challenge the plan, then they can do so through the SMC.

Activity 4: Working with the template

You should complete this activity with your deputy, a senior teacher or another school leader.

Choose an issue that you would like to tackle in your school. Using the blank template in Resource 1, work together to complete the template for that particular issue.

Reflect together on the task:

- Was it difficult to do?

- Did the template help to structure your thinking?

- How do you think the chair of your SMC will react to your plan?

Write down your responses in your Learning Diary.

4 Summary

This unit has explained how an SDP provides a guide for the year and beyond. It is best developed in consultation with stakeholders and is a powerful tool for enhancing learning and improving the school. The template provided in Resource 1 will help to structure your thinking about your plan, but it is not an end in itself.

The process of developing your SDP promotes community participation and shared responsibility by strengthening partnerships between school and community. It also supports ongoing self-evaluation and accountability. It is a document that is required as part of governance and accountability, but it is the process of developing, implementing, monitoring and evaluation that is the most important aspect. Ultimately, an SDP is driven by the ambition to raise the achievement of students through improving the quality of teaching and learning.

This unit is part of the set or family of units that relate to the key area of perspective on leadership (aligned to the National College of School Leadership). You may find it useful to look next at other units in this set to build your knowledge and skills:

- Building a shared vision for your school

- Leading the school’s self-review

- Using data on diversity to improve your school

- Planning and leading change in your school

- Implementing change in your school.

Resources

Resource 1: SDP template

Table R1.1 shows a completed SDP as an example. Table R1.2 is a blank template for your own use.

| Development priority | Detailed actions | Person with responsibility | Timescale | Resources needed | Success criteria |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Improve attendance of female students in school | Visit families with examples of the female students’ work to demonstrate their achievement and potential | School leader | This term | Make time | Parents are impressed and encourage their daughters to attend school |

| Use strategies in lessons to build the female students’ self-esteem | All teachers | Immediately | TESS-India units | Female students actively participate in lessons (evidence from learning walks) | |

| Run a careers evening in school and invite successful businesswomen | Sangay | October (before the main exams) | Event is well-attended | ||

| Carry out repairs to the female toilets and ensure all the doors will lock and toilets flush | Moses | Immediately | Building materials | Toilets in good order |

| Development priority | Detailed actions | Person with responsibility | Timescale | Resources needed | Success criteria |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

References

Acknowledgements

Except for third party materials and otherwise stated below, this content is made available under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike licence (http://creativecommons.org/ licenses/ by-sa/ 3.0/). The material acknowledged below is Proprietary and used under licence for this project, and not subject to the Creative Commons Licence. This means that this material may only be used unadapted within the TESS-India project and not in any subsequent OER versions. This includes the use of the TESS-India, OU and UKAID logos.

Every effort has been made to contact copyright owners. If any have been inadvertently overlooked the publishers will be pleased to make the necessary arrangements at the first opportunity.

Video (including video stills): thanks are extended to the teacher educators, headteachers, teachers and students across India who worked with The Open University in the productions.