Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Saturday, 7 March 2026, 9:56 AM

TI-AIE: Perspective on leadership: implementing change in your school

What this unit is about

This unit explores some of the methods and theories that will help you to implement change successfully in your school. There are many theories around change and it has been the subject of much educational research. These theories can be helpful because they provide a way for you to think about the implications of change and how to make it successful. Sadly, in education and elsewhere, much effort to make change happen meets with resistance and fails to result in the intended outcomes.

Many of the School Leadership units deal with the challenges of change. You may already have studied the unit Perspective on leadership: planning and leading change in your school, which introduces the importance of managing change so that it is effective and has impact. This unit focuses on the next stage – implementing change – so is useful if you have already studied the units on building a shared vision, self-review and development planning. In this unit you will be introduced to some ways of thinking about change that will help you as you try and improve your school. The case studies demonstrate how other people have managed to bring about change, often by creative thinking and a certain amount of cunning.

Resistance to change is normal and understandable behaviour according to Marris (1986), because we are attached to our current reality no matter how unsatisfactory that might be. Therefore, one of the biggest challenges facing school leaders is persuading the people who work in their schools to change the way they do things. This unit will help you to develop some ideas about how to overcome such resistance.

Learning Diary

During your work on this unit you will be asked to make notes in your Learning Diary, a book or folder where you collect together your thoughts and plans in one place. Perhaps you have already started one.

You may be working through this unit alone, but you will learn much more if you are able to discuss your learning with another school leader. This could be a colleague with whom you already collaborate, or someone with whom you can build a new relationship. It could be done in an organised way or on a more informal basis. The notes you make in your Learning Diary will be useful for these kinds of meetings, while also mapping your longer-term learning and development.

What the school leader will learn in this unit

- The nature of the change process and how people respond to change.

- Some key theories of change and their relevance to schools.

- How to work with and through others to implement change.

1 The change context

Ideally you have a vision for your school, and have carried out a school review that identifies new goals and actions. If these goals are about changing attitudes and behaviour, you may find the units on leading improvement in teaching and learning helpful, as they focus on changing pedagogy and practice in your school. There are likely to be other changes that you have identified, such as improving punctuality, attendance, the number of students completing their homework on time or attendance at parent’s meetings. You may find that you can make quite small changes that have a huge impact or that a change in one area has a beneficial effect in another.

Activity 1: A change in your school

Think about a change that you would like to bring about in your school. It might be improving some aspect of teaching and learning, or it might be something like changing the organisation of the school day, the homework policy or improving attendance.

Consider the following questions, noting down your thoughts in your Learning Diary:

- Why do you want to make this change in your school?

- Who will benefit from the change?

- Who will be affected the most by the change?

- Who is likely to resist the change and why?

Discussion

Before you embark on trying to change something in your school, it is important to think about the implications of the change. If you can anticipate who is likely to resist and why, then you can begin to think of strategies to involve them at the earliest possible opportunity.

Schools are under pressure. The government has set out an ambitious vision in the NCF 2005 and the ‘Right to Education for All’ Act of 2009. To realise this vision, schools will have to change. In the right conditions, Marris (1986) suggests that it is possible to transform the perception of ‘change as loss’ to one of ‘change as growth’. So when you as the school leader are considering challenging any embedded habits and practices in a school, you need to recognise that how you help others to see change as growth is probably the single most important aspect of your work in leading the change process.

Some of the changes that you need to make in your school will be externally imposed (deterministic); others will be ideas that have come from within the school community (voluntarist). The leader must work in the legal context of what is required of schools and address legislation, but how this is done is still open to interpretation. Successful headteachers in modern schools take responsibility for improving schools. This automatically means addressing change, because you are preparing students to be successful future citizens in an increasingly complex world. Changing attitudes mean that in the past, staff and community members may have readily accepted the word of the school leader as the basis for action, even if they implemented actions unwillingly or without understanding. Now leaders must develop team approaches if they are to implement change effectively.

School leaders need to promote necessary change and manage any resistance, and also prioritise the changes that will have maximum impact. This unit starts with a brief examination of a number of theories of change that will help you to understand the issues and principles behind successful change.

2 Some theories behind change, planning and implementing change in school

There are three theories of change that are relevant to the work of school leaders. These theories are not recipes for change, but provide a way of thinking about change. The leader cannot change what has happened in the past but has considerable scope to influence how individuals respond to change in the future, and their commitment to it.

Theory 1: Change as a series of steps

Knoster et al. (2000) saw five dimensions of change (Figure 2).

Knoster et al.’s work showed that if any one of these dimensions was missing, the change was likely to be unsuccessful. This has been captured in Table 1. A tick (![]() ) indicates a dimension that is in place; a cross (✗) shows where a dimension is missing. For example, where there is no vision (as in the first row), there will be an outcome of confusion because the reason for change and the intended outcome is unclear.

) indicates a dimension that is in place; a cross (✗) shows where a dimension is missing. For example, where there is no vision (as in the first row), there will be an outcome of confusion because the reason for change and the intended outcome is unclear.

| Vision | Resources | Skills | Incentives | Action planning | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ✗ | Confusion | ||||

| ✗ | Frustration | ||||

| ✗ | Anxiety | ||||

| ✗ | Complacency | ||||

| ✗ | Gradual change | ||||

| Effective change |

One word of caution surrounds resources. Resources include human and material resources. Many changes in school can be made within existing material resources or through relatively minor additions. The most significant resource in most educational change is the human resource. A poor teacher in a high-tech classroom is still a poor teacher. A good teacher with few resources is still a good teacher.

Case Study 1: Mrs Gupta wants a change in teaching

Mrs Gupta is school leader of a mixed secondary school in an urban area where there is a wide range of students.

I visited a nearby school that was getting good results and saw teachers using a variety of teaching methods that involved the students actively in lessons. There was groupwork and independent work, and the teachers used many questioning techniques to get students to think about what they were learning. More able students often helped those who had difficulty recording work on their own, and the teachers had made a variety of materials such as flashcards and pictures to make their lessons more interesting. Much of this, along with student work, was displayed on the walls.

Back at my school, I decided that we need to make some changes to the teaching in our school. I called a staff meeting and I told my staff what I had seen and how good the school was. I explained that I wanted students to be more actively involved in their learning and that I wanted everyone to plan a lesson next week using groupwork. I would be visiting them in classes to see how they were progressing.

Activity 2: What did Mrs Gupta miss out?

Refer to Table 1 and then note the answers to these questions in your Learning Diary:

- What elements of the change process did Mrs Gupta miss out?

- How effective is her attempt to bring about change likely to be?

- What else does she need to do?

Discussion

Mrs Gupta had a vision that she explained to the teachers in her school. However, it is not clear that they understood or agreed with her vision. She made a plan and she introduced an incentive – that she would be visiting their classroom. For the teachers, that probably felt more like a threat. Teachers need to be motivated, and this is a key leadership responsibility. Effective incentives (rather than threats) are about recognition, receiving praise and being part of a successful team.

She didn’t provide any resources to support the teachers, or check that they had the necessary skills. If she had talked to the school leader from the other school, she might have gained advice and evidence to help her articulate her vision to her staff. Also, she might have been given some tips about the resources and skills that were developed.

Resources were not needed to start work on the project, although they would help in many ways. For example, Mrs Gupta could have offered to take some classes so that teachers could visit the nearby school and see for themselves the sorts of things that she wanted them to do.

Mrs Gupta made a plan but it was unrealistic because she expected instant change rather than a planned approach in which staff could try out ideas in a developmental manner.

Case Study 2: Mr Chadha leads a new approach to assessment

Primary headteacher Mr Chadha attended a course on embedding continuous and comprehensive evaluation (CCE) in his school.

The course explained all the reasons for CCE and gave some really convincing examples that showed how CCE can improve learning. I went back to school feeling really inspired. In the next staff meeting I explained CCE to my staff (I have six teachers working in my school) and said that in the next few weeks they would all have the opportunity to attend a course at the DIET [District Institute of Educational Training]. They could see how enthusiastic I was and welcomed the opportunity to learn more. I also explained that I would be asking the SMC [school management committee] if I could reorganise the budget to buy some resources for their classrooms to support CCE.

They came back from the course with plenty of ideas and a detailed training manual. For the first two weeks, there was plenty going on. When I was walking around the school, I could hear teachers asking more questions, giving encouraging feedback and checking understanding. But then there was a week’s holiday and when we came back, it was as if everything had been forgotten. The training manuals remained on the shelf and the teachers were teaching in the way that they always had. I did not know what to do.

I decided to investigate. I spoke to the two teachers who had been the most enthusiastic about the course. They agreed that CCE sounded good in theory, but that it was hard to do – it was taking longer to plan lessons and they were worried about finishing the syllabus. One was finding it difficult because he had 60 students in his class.

I realised that this was too much change too soon. The teachers had quickly forgotten the course and that one course was not sufficient for them to develop the skills required. I needed a new plan.

I invited the trainer to come to school to talk to all of us in a staff meeting and to give some practical examples for CCE in action. I then divided the teachers into groups of three. The idea was that they would mentor and coach each other. I asked each teacher to focus on CCE for one week, with the other two acting as mentors. So at the end of three weeks, everyone had had the opportunity to try out new techniques. Each day, one group of three missed assembly and used the time to discuss their plans for CCE and receive feedback. I also encouraged them to visit each other’s lessons, and I offered to teach their classes so they could do so.

This worked much better. After three weeks, everyone had had the opportunity to focus on CCE with the support of two colleagues. The mentoring process had also been helpful. Everyone decided to carry on the work for another three weeks, with each teacher concentrating on CCE for one week and supporting others for two weeks.

Case Study 2 demonstrates that even if all the elements of change are present (vision, resources, skills, incentives and action planning), then the change might not be successful. In this case, developing the skills required was more difficult than Mr Chadha expected – teachers needed ongoing support and encouragement rather than a single training course.

Theory 2: Change formula

No theory of change is a perfect description of how change happens, but it can help a leader to think about change in their context. Gleicher’s change formula (quoted in Beckhard, 1975) is another theory that can be helpful when embarking on the change process. The formula charts the necessary qualities that the change needs to contain if it is to become embedded in your school.

The formula is:

D × V × F > R

It is explained as follows:

- ‘D’ is the need for change already being registered by people’s dissatisfaction with the reality today.

- ‘V’ is the vision for change being sufficiently compelling that most people are able to visualise what is possible.

- ‘F’ represents the first steps towards implementing the change being valued by the whole community.

- If the previous three are in place, then it is likely that together their impact will be greater than the inevitable and understandable resistance (‘R’) that there will be to the change.

The challenge for a school leader is to persuade teachers that they are ‘dissatisfied’ with the thing that you want to change. Your teachers are likely to be ‘dissatisfied’ by a number of things, such as a lack of resources, the size of their class, the amount of work they are expected to get through or the number of students completing their homework on time. They are less likely to be ‘dissatisfied’ with the amount of participatory learning taking place in their classroom, or the amount of CCE that they are doing.

There are a number of things that you can do to motivate your teachers and persuade them to make the sorts of changes that you desire. Here are two examples from school leaders in India:

- The teachers in Mr Aparajeeta’s school were always rushing to complete the syllabus. He had noticed, however, that the exam results were consistently poor. Even though the teachers were covering the whole of the syllabus, only half of the students could achieve the 40 per cent grade that was required to pass. Mr Aparajeeta decided that it would be much better for them to teach key concepts properly so that students really understood them, rather than to cover every detail in the textbook. After all, the students all have the textbook and if they understand the work they are more likely to be motivated to read it for themselves. He therefore told his teachers that they did not have to stick rigidly to the textbook. They could introduce a new topic however they wanted, as long as it engaged the students, and they had to pick out the activities that related to the key concepts rather than try and do every activity. He encouraged them to work in departmental groups to identify the key concepts and created time for subject group meetings by not holding any staff meetings for a term.

- Mrs Kapur was frustrated because her teachers would not complete the marking sheets for tests and exams so she could not do a proper analysis of how each year group was progressing. They marked the tests and handed them back, but then said they did not have time to keep records. She said that they would need the record sheets for the parent’s meeting, but some of the teachers pointed out that hardly anyone came to these meetings. Mrs Kapur went to the local village to talk to some of the parents. She listened as they told her about their farm and how busy they were. She used an analogy to explain why they should come to the parents’ evening. She pointed out that when they had planted their seeds, they didn’t just leave them in the field. They checked regularly to make sure that they had enough water, that there were no pests and that the plants were thriving. They needed to do the same for their children. She explained that their child was like a seed and that they should take the opportunity to check that they are learning and thriving at school. At the next parents’ evening, the attendance was much better. Some of the teachers were embarrassed because they were not able to show the parents detailed records of their child’s progress. The record-keeping in the school soon began to improve and Mrs Kapur was able to analyse progress more effectively.

In the first example, Mr Aparajeeta tackles an issue that his teachers are already dissatisfied about. In the second example, Mrs Kapur has to employ a certain amount of cunning in order to create the circumstances in which the teachers realise for themselves that they need to keep records of student progress. Other strategies that you could use include the following:

- Making it clear that the change is coming from the government and that you are all going to work together to make it work.

- Involving teachers in the school review process (see the leadership unit on school self-review) so that they have first-hand knowledge about how the school is performing.

- Encouraging teachers to take responsibility for issues in their class. This could be attendance, the proportion of students completing their homework, appearance, punctuality or the smartest classroom. You could do this by instigating a weekly award for the class which performs the best in your chosen category.

Pause for thought

|

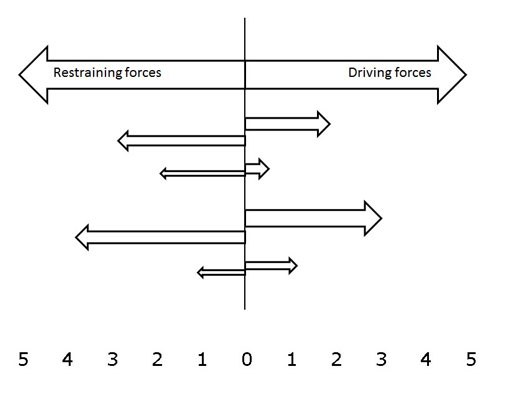

Theory 3: Force field analysis

Another theory of change is ‘force field analysis’. This approach to change encourages you to focus on the conditions that are already in place that will firstly support the change and secondly identify the likely sources of resistance.

How to do a force field analysis:

- State clearly the change that is wanted.

- Draw a vertical line from the statement of change down a large piece of paper (or on a board or computer screen).

- Draw the driving forces on the right-hand side of the line and the restraining forces on the left.

- For each force the length of the arrow (from 0–5) reflects the extent of the factor, with 5 being the most powerful.

- The thickness of each arrow represents the relative importance of the force.

In the following case study, Mr Agarwal uses force field analysis to help plan a change in the approach to homework in his secondary school (although it could be used in a primary school as well).

Case Study 3: Mr Agarwal tackles homework

During my learning walks last term, and conversations with teachers in the staffroom, I noticed that there was a great deal of dissatisfaction with the homework that students were doing. It was often rushed, untidy, incomplete or simply not done. Teachers felt frustrated because students were missing out on the opportunity to consolidate the work, and they felt as if they were continually nagging rather than building positive relationships with their students.

I held a staff meeting at the beginning of term and explained that I wanted us to tackle this issue together. I quoted things that I had seen and things people had said, and very soon there was an animated discussion about the poor level of homework. I held the meeting in a classroom so that we could use the blackboard to do a force field analysis.

The change that we wanted to bring about was to improve the quality of homework done by students. We tried to think about all the things that could help us with this and the things that might make it difficult.

This is what we came up with as driving forces:

- Parents are keen for their children to be set homework.

- A carefully planned homework exercise can support learning.

- Setting homework helps us to finish the syllabus.

- The NCF 2005 expects us to set homework.

- All schools set homework, so we could go and talk to colleagues from another school to see how they tackle this issue.

- The SMC expects students to be set homework on a regular basis.

And here are the restraining forces we identified:

- Some students are expected to do household chores in the evening and have no time to do homework.

- It is difficult to think of suitable homework exercises, so we often resort to copying notes from the textbook, which must be a bit boring for the students.

- Planning lessons takes a long time – planning homework as well is really difficult.

- Homework creates a huge amount of marking (‘I have 60 students in my class and I cannot possibly mark their homework, so it feels like a waste of time’).

- Students just copy each other’s homework, which is a waste of time.

- The observation that it is impossible to check everyone’s homework, which for some of the students is an excuse for not doing it.

Activity 3: Using force field analysis in your school

Look at the list of driving forces and restraining forces that Mr Agarwal and his teachers made in Case Study 3. Now try to put these into the same format as Figure 4, with the longest arrows for the most powerful issues (for example, the SMC monitoring homework) and the fattest arrows for the most important (such as teachers setting appropriate homework). Put the most important factors at the top of your figure. Using Mr Agarwal’s list gives you a chance to practise this method.

As you draw a figure in your Learning Diary, consider whether there is anything that you would add to the list from your own context and what you could do in order to harness the driving forces and reduce the restraining forces.

Discussion

By first listing and categorising the issues, and then giving them weight, you can prioritise your efforts to tackle the restraining forces and make the most of the driving forces. It is easy to lose sight of what is important and what drives change. Such graphic representations can help you to organise your findings and share them with others. Read Case Study 4 to see what Mr Agarwal did in order to bring about change.

Case Study 4: Mr Agarwal identifies the forces at play

After we made our lists, we decided that the biggest driving force was the opportunity that homework gives for finishing the syllabus. We may set the task of reading some of the textbook, but many teachers admitted that they never check that the work has been understood. One of the smallest driving forces was the support from the parents. This was because we live in an area where many parents have not been educated themselves and cannot see the point. (I also noted privately that one of the biggest driving forces was Ms Nagaraju, a teacher who seemed to be very enthusiastic about the whole exercise and determined to improve homework in her class.)

The biggest restraining force seemed to be the expectation of students to do chores, or paid work in the evenings. (Although, privately, I noted that the extra planning involved in setting good quality homework exercises that support learning was clearly a problem, and Mr Meganathan, who has been teaching for 20 years, was very negative.)

Change theories

Each of the change theories described provides a slightly different perspective and stresses slightly different things. However, they share several characteristics. Change is affected by:

- individuals’ responses to the current situation

- the understanding of what the change will look like (visualisation)

- motivation to make the change

- previous experiences

- the means to carry out the change – resources and skills

- planning.

Activity 4: Why do changes fail?

You will have experienced many changes in your role as a teacher and school leader. Think of a change or initiative that was less than successful. Maybe it failed to enthuse people, or was poorly timed or just too ambitious. It may have been a change that you organised, or perhaps it was organised by someone else. Use the theories described above to identify why it failed.

If you were involved in the change again, what could be done differently? Try and identify something from each of the theories that would make a difference. You may find it useful to share your ideas with another school leader, as discussion can bring out other interpretations and perspectives.

Discussion

The change might have failed because one of the steps in theory 1 was not completed, or was underestimated. It might be that there was insufficient dissatisfaction with the present (theory 2), the vision was not clear enough or the first steps were too ambitious. It is possible that the people leading the change did not take account of the factors that could help them or would restrain them (theory 3).

Alternatively, despite all the careful planning, it is possible that the change was just too ambitious for one person working alone. Change is often more effective when a team is leading it.

3 Establishing a change team

Ownership of change is critically important. Leaders cannot make change happen themselves. They must work through others and influence them to cooperate. This is best achieved where there is a climate of positive teamwork and commitment to learning together and making improvements.

One technique that has proved very useful is to establish a change team. It is important that changes are not wholly dependent on the leader and that there is wider ownership from those who will be responsible for its implementation.

Composing the change team and determining its brief will depend on your context. However, there are some key factors to be considered:

- Champions: Some staff and stakeholders will be more enthusiastic than others and/or be more able in terms of understanding what is involved. It is important that some of them are involved in driving the change forward. This may challenge assumptions often held that power and influence derive from seniority. Younger staff may well be more able to address change.

- Representation: If the change is significant it will affect all stakeholders, and your change team needs to be representative of all aspects of the school community. It might include staff with responsibility, younger staff, staff from different subject areas and SMC members, as well as parents, community members and students.

- Challenge: Although tempting to consider including only those who support the change, there can be merit in including some who are unsure of the change or oppose it. This allows issues to be addressed during planning and shows that the views of all are considered.

- Size of team: Do not make the team too large or it will become hard to manage and secure agreement. The size may depend on the school size, but six to eight is probably a good number and there will be problems if you go much above ten.

- Organising the team: You need to decide whether team members are representing different groups and, if so, how they share information with their colleagues or peers and ensure that they reflect the views of those they represent. It may be that the members are not expected to be representatives of a group, and that communication to the wider groups will come from the team as a whole and/or you as a leader.

- Role of the team: You will need to determine the extent of the team’s brief; what are the limits of their power? Are they advising, recommending or making decisions? If they are making decisions, within what limits?

- Your role: Delegation is a sophisticated skill and there must be clear understanding of what the team can and cannot do. This will depend on your involvement. Nothing can be more frustrating for a group than to spend much energy on determining what will happen, only for a leader to dismiss its suggestions completely. It is likely that you will want to attend some meetings and, even more importantly, get regular feedback from the group about progress being made. Resist any temptation to take over the group while you are there!

- Chair of the group: Your role with the change group will be simplified if a chair is appointed (and you can decide whether you appoint the group or allow the group to choose its own chair) so that you can liaise regularly and influence ongoing activity and ensure communication with the wider staff and stakeholder groups.

- Subgroups: If the change is complex, then at some stage you may wish to establish other small groups to examine particular aspects of the proposed change in detail.

- Timescale: You should be clear about timescales but be prepared to review these regularly. Most changes take longer than originally thought and it is better (within reason) to ensure understanding and thorough planning rather than start too soon without adequate preparation.

Case Study 5: Mr Agarwal builds a change team

I decided to set up a ‘homework team’ of five. I asked my deputy to lead the team and I made sure that it included Ms Nagaraju and Mr Meganathan, a parent representative from the SMC, and Mrs Chakrakodi – another teacher who was almost as enthusiastic as Ms Nagaraju. I had a meeting with my deputy in order to make sure that she understood what I wanted her to do and we agreed that she would report on progress each week.

They conducted a survey of students in order to learn more about their homework habits and they held a meeting in school for parents. They even visited the homes of some families. They also went through each chapter in the textbook and carefully planned one homework exercise that really tested understanding and would therefore consolidate learning, so that teachers did not have to plan everything themselves. They also used one of our regular staff meetings to talk about ‘peer review’ and ‘self-review’, using the TESS-India units, so that teachers could understand that students could get feedback from each other as well as from them. The student survey suggested that they would feel more motivated if they had more choice in how they presented their work, or had the opportunity to carry out independent research.

Activity 5: Your change team

Consider the advantages of Mr Agarwal’s team composition and then think about your own school. If you were to implement a similar change to Mr Agarwal, decide in your Learning Diary who would be on your team and indicate why each person would be chosen (their expertise, cynicism, authority, insight, etc.). Decide if you would chair the change group or delegate this responsibility. If you delegate, how will you monitor progress?

Discussion

Mr Agarwal chose to have a small change group. He included the most enthusiastic and the least enthusiastic teachers, hoping that Ms Nagaraju and Mrs Chakrakodi would persuade Mr Meganathan that this was a good idea – although that was a bit of a risk on Mr Agarwal’s part. It was important that his deputy was an ally, otherwise the change could easily go astray.

With your change team, you need to think not only of the different contributions, but also how to make the best of the different personalities. Clear focus and outcomes are essential, so the chair needs to be strong.

4 Monitoring the change

It is important that changes are monitored in order to see if they are being successful. The monitoring needs to start at an early stage so that the plan can be changed if necessary, and so that early successes are noticed and celebrated. The team that is responsible for managing the change needs to think about possible indicators and the performance level that is expected.

‘Indicators’ could include anything that provides evidence that change is taking place. This could be obvious things, such as work in exercise books or the number of students completing their homework. Alternatively, it could be things like overheard conversations between students, feedback from parents or a change in the attitude of certain students and teachers.

‘Performance level’ will be something more concrete such as:

- 90 per cent of students regularly completing their homework

- every teacher setting at least one homework exercise per week that gives students some choice about how they do it or what they do

- every teacher setting one open-ended task per week.

Activity 6: Monitoring change

Think about a change that you would like to bring about in your school. How will you know that change is taking place? List three indicators that you could use to monitor the change in your Learning Diary.

What performance level would you look for? List three measures that you could use to check the progress of change.

Discussion

It is important that performance measures are realistic. The change team needs to experience some early success in order to keep them motivated! You can increase the expectations as the work progresses, but early performance measures should be set at a realistic level, slightly above the current situation.

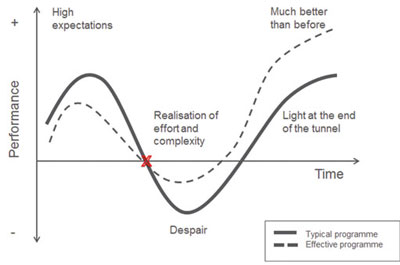

5 The change curve

Change does not happen in a linear way. Those who have studied change show that the change curve in Figure 6 is indicative of our response to change. The trouble is that in any school there are many different individuals who will go through the process at different rates: some may be at the end of the process when others are still at the beginning. The important message for the leader is that you observe carefully how individuals and groups are responding to the change and take appropriate actions to support (or challenge at times) those who are finding it especially difficult to adjust to change.

At the start of the change process there is often enthusiasm, interest and optimism, leading to an improvement in performance for many. As the change is understood and the recognition of all the complexities in performance grows, confidence can drop and performance levels fall in what is known as the ‘dip’. This is normal, but the leader can do much to ensure that this dip is neither too deep nor too long-lasting.

Some of the ways a leader can minimise the dip are as follows:

- Observe and listen: The most important thing a leader can do is to observe and listen. It is still important to look beyond the change group and have conversations with individuals or groups about their concerns. By listening you will encourage trust in you and in the change.

- Optimism: The leader must keep communicating the vision and be optimistic about achieving outcomes. At times, as a leader you may experience doubt – but this should not be shared, as it is likely to reduce confidence.

- Adjustment: Your vision for the change should not alter, but you should be able to make adaptations and adjustments along the way that take account of conversations and emerging issues.

- Do not plan in too much detail at the start: Fullan (2013), perhaps the leading western educational researcher of change, suggests that plans should be ‘skinny’ and not include too much detail at the start. Coyne (2014) writes that ‘people are hard to predict. And therefore looking far ahead in time at how they might behave in response to a change you haven’t started to implement is dangerous and, at best, guesswork.’

- Quick wins: Look for early signs of success, and publicise and celebrate these. This not only promotes confidence but also the commitment to be part of something that is being seen as successful.

Case Study 6: Introduction of activity-based learning

In 2004, India’s government introduced ‘activity-based learning’ (ABL). In 2004/5, states provided training programmes for all teachers and there was enthusiasm for the initiative. By 2007/8, people were beginning to realise that ABL was more difficult to implement than they thought. By 2008, teachers in many areas had given up and resorted to more traditional methods. The ‘high expectations’ and enthusiasm slipped into ‘despair’.

Implementing a programme that requires all teachers in all schools to change is hugely ambitious. Sustainable change has to take place gradually and needs to involve the people who are responsible for implementing it.

The TESS-India materials – freely available online – will help teachers to make small changes that will bring about improvements in their classrooms. The videos show participatory teaching approaches in action in Indian classrooms. These resources will help you and your teachers to move beyond the ‘dip’ to real improvements in teaching and learning.

6 Overcoming barriers

Look back at the force field analysis earlier in this unit. You will see that there are forces for change and resistance, or barriers to change. To implement a change successfully involves either increasing or strengthening the forces for positive change, or reducing or eliminating the barriers to change – or doing both.

Activity 7: School leader actions

Look back at the approach adopted by Mr Agarwal in Case Study 5. In your Learning Diary, list which actions were about strengthening the positive and which were about reducing the barriers.

Discussion

In order to strengthen the drivers, Mr Agarwal’s change team involved the parents and promoted collaborative working in order to support teachers with their planning. In order to reduce the barriers, Mr Agarwal included one of the most resistant teachers in the change team. He found out more about the students’ perspective and supported teachers in implementing peer review and self-review.

Case Study 7: Mr Thapa sets about leading a change

Mr Thapa was a conscientious teaching school leader who attended a briefing confirming details of the state’s implementation of the Right to Education Act 2009 (RtE), including the banning of holding back promotion to the next year group. When he returned to the school, he knew what the staff reaction would be, and he was tempted to raise his hands in the air mouthing, ‘kya karein’ – ‘It’s not my fault; we have to make the most of a bad job!’

He believed that inclusion was right, and he thought a lot over the weekend about how to approach the first staff meeting. Over the weekend the media had got hold of the launch of the RtE and so everyone was in a state of anxiety about what it would mean. When his meeting started on Monday, the wall of sound that greeted him was immense. Staff wanted to let their frustration out about someone having made their job even tougher. What Mr Thapa did was very simple. He told them about the RtE and some of the benefits that it could bring to their students, to the aspirations of the next generation and the benefits in the much longer term that they would reap in smaller class sizes. He certainly did not blame anyone. It was what he said at the end of the meeting that helped the staff to stop, listen and reflect.

I know I don’t teach as many lessons as the rest of you [Mr Thapa told the staff], but I do teach every day, so I understand why you are upset. But if we’re really honest, how many of us actually stay behind at the end of the day to keep students back? And when did the threat of no promotion stop a student being lazy or naughty? Listening to you, I think your concerns are also about how we can help our students to succeed – and yes, of course, what we can do to make sure that the naughty students don’t become even more difficult. Today when I went on my regular daily round, I saw some lessons in which the students are always interested, in which behaviour is rarely a problem and in which the students are learning. That will continue whatever the government says.

Today reminded me that my main job is not about filling in forms and sitting in my office. What I want us to do today is to start a discussion among ourselves about how to make our classrooms more interesting no matter how many students are in them, about how to learn from those teachers in our school who inspire me as well as the students, and work out how to share their DNA with the rest of us. And – most importantly – how to involve the students themselves in working out what their responsibility is to make learning more enjoyable and teaching more productive.

Activity 8: Identifying Mr Thapa’s leadership skills

In your Learning Diary, list the skills and behaviours that Mr Thapa used to encourage his staff to support him. Think about how he showed leadership, but also what skills and behaviours he used to inspire others to follow him. Think about how far you also use these skills, and which ones you might think about developing further.

Discussion

Mr Thapa was positive and optimistic and helped staff to see a way forward. He was able to help them see the vision of the RtE and its intended outcomes, rather than dwell on practical issues. He took responsibility for what was happening in his school and did not try to place blame on others. He showed that he understood the practical issues faced by teachers but showed a way forward, building on existing good practice in schools. He understood staff concerns and did not personalise issues into ‘Me as a leader against the staff’. He showed an ability to analyse and research, and to reflect on what was the best way forward for his staff.

7 Summary

In this unit you have been introduced to some theories of change and the significant challenges in ensuring that change is introduced and implemented effectively. It is important to reflect carefully about change before you act so that you will bring people along with you. The three theories of change and the ‘change curve’ provide a way of thinking about change that bring helpful insights to the process.

You have been made aware of a number of techniques that will support you in leading the change process and have seen, from case studies, the leadership skills that are required to lead and implement change effectively. You may wish to read further and perhaps share some of the theories of change with the people you work with in and around your school.

This unit is part of the set or family of units that relate to the key area of perspective on leadership (aligned to the National College of School Leadership). You may find it useful to look next at other units in this set to build your knowledge and skills:

- Building a shared vision for your school

- Leading the school’s self-review

- Leading the school development plan

- Using data on diversity to improve your school

- Planning and leading change in your school.

References

Acknowledgements

Except for third party materials and otherwise stated below, this content is made available under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike licence (http://creativecommons.org/ licenses/ by-sa/ 3.0/). The material acknowledged below is Proprietary and used under licence for this project, and not subject to the Creative Commons Licence. This means that this material may only be used unadapted within the TESS-India project and not in any subsequent OER versions. This includes the use of the TESS-India, OU and UKAID logos.

Grateful acknowledgement is made to the following sources for permission to reproduce the material in this unit:

Figure 2: adapted from Knoster, T., Villa, R. and Thousand, J. (2000) ‘A framework for thinking about systems change’, in Villa, R. and Thousand, J. (eds) Restructuring for Caring and Effective Education: Piecing the Puzzle Together, pp. 93–128. Baltimore, MD: Paul H. Brookes Publishing.

Figure 6: adapted from Davies, R. (2012) ‘CRM implementation – the effect on users (part 1)’, http://www.contactedgecrm.com/ 2012/ 03/ 09/ crmimplementation-theeffectonusers-pt1/.

Every effort has been made to contact copyright owners. If any have been inadvertently overlooked the publishers will be pleased to make the necessary arrangements at the first opportunity.

Video (including video stills): thanks are extended to the teacher educators, headteachers, teachers and students across India who worked with The Open University in the productions.