Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Wednesday, 4 February 2026, 9:34 PM

TI-AIE: Orientation: the elementary school leader as enabler

What this unit is about

There have been many changes in education policy in India in recent years, but one of the most significant is the shift in expectations on schools. The aspiration is that schools should become more autonomous and responsive to their local communities, and that school leaders should take greater responsibility for the quality of teaching and learning in their schools (Tyagi, 2011).

The aim of the TESS-India Open Educational Resources (OERs) is to support school leaders that want to enable their schools to become dynamic learning environments with active students and interactive teachers. It can be a challenging task to bring about such practice where it does not already exist, although school leaders have a great deal of authority within their own school. This unit positions the school leader as an enabler – someone who uses their role to make things happen in their school. The TESS-India OERs provide a ‘toolkit’ to support you in this role (see Resource 1 for further details).

This first orientation unit aims to familiarise you in how to use the TESS-India School Leadership OERs for your own development. At the core of all these resources is the idea that learning is lifelong and continuous: for teachers to learn effectively, their school leaders also need to be learners.

Learning Diary

During your work on this unit you will be asked to make notes in your Learning Diary, a book or folder where you collect together your thoughts and plans in one place. Perhaps you have already started one.

You may be working through this unit alone, but you will learn much more if you are able to discuss your learning with another school leader. This could be a colleague with whom you already collaborate, or someone with whom you can build a new relationship. It could be done in an organised way or on a more informal basis. The notes you make in your Learning Diary will be useful for these kinds of meetings, while also mapping your longer-term learning and development.

What you can learn in this unit

- To review your school leadership skills and identify areas for improvement.

- To use the TESS-India School Leadership OERs to design your learning pathway that enhances your school leadership skills.

- What it means to be an enabler of learning in your school.

1 Being a school leader in India

The Right to Education Act (RtE) 2009 gives schools in India more autonomy than they have had in the past. This has already happened in many other countries, with school leaders often having responsibility for their own budgets, the power to recruit their own teachers and even being able to decide on the curriculum. These changes bring more responsibility but also more freedom, and the expectation that school leaders will work towards improving their school without waiting for instructions from the district education office or other educational authorities. In India, the work of the National College of School Leadership (NCSL) at the National University of Education Planning and Administration (NUEPA) is supporting these changes.

TESS-India provides a bank of Open Educational Resources (OERs) that includes 20 study units for school leaders. These are designed to provide learning activities on various aspects of school leadership. Some focus explicitly on improving teaching and learning, and developing your teachers’ classroom practice; others focus on the processes and systems in schools, such as building a vision, conducting a school review, creating a development plan and working with the community that your school is located in. You can select the OERs that meet your own professional learning needs. The units are grouped in accordance with priorities identified by the NCSL for school leadership, but they are not a course – you are encouraged to create your own route through the units.

Each unit has activities and case studies. The activities are for you to carry out in your school; some of them involve working with colleagues and some of them you will do on your own. Rather than being designed to create extra work, they help you reflect on and gain a better understanding of things that you are doing anyway or were thinking of doing. Each unit is designed to be coherent, but you might still choose to do individual activities rather than a whole unit. The OERs respect the knowledge and experience that you bring to your role, and encourage you to work collaboratively.

In this introductory unit you will start by thinking about your own professional development. You will consider what knowledge and skills you already have and how you might develop your practice as a school leader.

TESS-India also provides OERs for teachers. All the OERs take a social view of learning, where learning takes place through participation in practices with other colleagues and students in your school. They are not detailed recipes for best practice or instructional materials; instead, they encourage you and your teachers to develop reflective and discursive identities and roles. The aim is to be open about learning and inquiry, towards the possibility of solving problems within one’s own working environment, whether that be your school or your classroom (Lave and Wenger, 1991; Bruner, 1996; Wenger, 1998).

Pause for thought Think back to the start of your career as a school leader or a senior teacher.

|

2 Thinking about your own learning as a school leader

In order to make the most of new opportunities, school leaders will need to develop a greater range of skills. You have probably become a school leader because you are a good teacher and you are well qualified. Being a leader, however, is very different from the role of teacher. Your role is to manage the day-to-day running of the school and to ensure that, over time, the school provides the best possible education for the students in its community. In this unit you will be introduced to some of the skills and competencies that an effective school leader needs to develop to help the teachers in your school to become more effective.

Pause for thought Think back to when you were at school or when you started your teaching career. Now think ahead about ten years. What will be the most striking differences between schools in ten years’ time and the year in which you started your career? |

Activity 1: Your professional development as a leader

- Using your Learning Diary, write down five words that you would say characterises you as a leader.

- How do you think your teachers view you as their leader? Do they like you? Do they respect your knowledge and skills, not just your position? Why do you think this is the case? How do you demonstrate to your teachers that you are developing as a professional? For example, would they see you as someone who is willing to try new ideas and reflect on their impact?

- Reflecting on your answers to Questions 1 and 2, what do you see as obstacles to your own professional development as a leader?

Discussion

Your responses will be personal to you and your context. However, considering three different types of leader might help you to reflect further on the challenges that you may face:

- The first type may be someone with many years’ experience of leading a school, who feels confident doing so but finds it difficult to show other members of staff that they are still learning and changing their own practice. This may be because they want to appear confident and in charge, and therefore keep professional development as something private and hidden.

- The second type of leader may be someone who is younger and concerned about losing authority if they are seen to have areas for personal development. They may be aware that they have less expertise in the classroom than some of their more senior teachers, but they have a lot to give in a model of leadership that combines enthusiasm, with vision and an understanding of the latest ideas, which at the same time respects the expertise of other teachers.

- Finally, there may be a group of leaders who – despite being willing to develop their practice, and doing so in a transparent way to others – never have the time to devote to such activities. These are leaders who, subconsciously, are modelling an attitude to professional development that may undermine efforts to bring about change in their schools.

The qualities of a good leader are well documented. Table 1 has some suggestions about how these apply to the Indian context. You will return to this analysis in Activity 3.

| Qualities of a good leader | What these might mean in your context |

|---|---|

| Readiness to confront authority | You will need to work with your district education office and other related structures such as the cluster resource centres (CRCs), block resource centres (BRCs), local panchayat and school management committees (SMCs). These provide valuable resources and in many parts of the country still take responsibility for recruiting and deploying teachers. It is important that you manage your relationship with all these institutions and functionaries carefully and sensitively. Confrontation might not be the best approach, but don’t be afraid to take the initiative or do things differently from how they have been done in the past if you think it will help your school. |

| Being prepared to take risks | Culturally this is difficult, because India’s hierarchical structures mean that people feel they need to seek approval for any initiative from a more senior person. However, as long as you are aware of district priorities and the school development plan (SDP), and you have well thought out reasons about why you are making a particular change, you should be able to take risks in your school in order to achieve the improvements you want. |

| Resilience in the face of failure | In many cultures, admitting you have made a mistake or that things are less than perfect is difficult. Managing change is demanding and will not necessarily go smoothly. Every time something does not go exactly as planned, you should regard this as a learning opportunity. Make sure you reflect on and identify the reasons why things have not gone as planned, but don’t be afraid of admitting that you could have done something differently. |

| Confidence in instinct and intuition | You will probably have experience of working as a teacher in different schools. You will be able to use and build on this experience in your role as a school leader. The new aspiration for autonomous schools means that you will have more freedom to be creative and try out new things. |

| Ability to keep in mind the bigger picture | This applies to all leaders. Your role is to establish and communicate a clear vision for your school. All actions and initiatives should be linked to this vision. There is a School Leadership OER that provides practical advice about how to work with others to build a vision for your school. This will help you in formulating the SDP with the SMC members. |

| Moral commitment | The values and beliefs that underpin the NCF 2005, the NCFTE 2009 and the RtE 2009 challenge some traditionally held beliefs. In order to meet the aspirations set out by the government in these documents, you will need to understand the underlying values of these policies and model these in your school and the local community around your school. |

| A sense of timing and the ability to sit back and learn from experience | As you start to evaluate your school, it is possible that you will identify a number of changes that you wish to make. It is important not to try and change too much, too soon. You will need to prioritise and move slowly, taking all the teachers with you. |

Case Study 1: Mrs Aparajeeta enquires about learning

Mrs Aparajeeta is a headteacher in a rural elementary school where the district education officer had told her not to expect much, because ‘they are rural children and find it difficult to learn’. When she started there were 69 students on the role.

On the first day, I was excited to get started, but disappointed to find that only 45 students lined up in the playground. My assistant teacher said that this was good – there were usually only 30 – and that they must have come to see the new school leader. She was right – the next day there were only 32, and some of them ran away after lunch.

After school, I walked into the village and was surprised at how many children there were playing outside, working on market stalls and working in the field. I spoke to a young boy of about nine who was mending punctures in bicycle tyres. I asked him why he did not come to school. He proudly told me that he earned Rs. 100 a day mending tyres and that he did not need to go to school. The things they taught him were not important compared to his work. I talked to some of the parents and found the same attitudes. The children found school uninteresting and not relevant, and their families needed them to work.

I decided I needed to do something about it, so I changed the timetable. I added two ‘activity’ periods – one after assembly in the morning and one after lunch. In those lessons we taught the students practical skills, art and craft. We soon put the things they had made on display. Word got round and more students started coming to school. I was disappointed at how dirty and untidy they looked. I made another visit to the village and explained to a group of mothers that we start the school day with assembly and a prayer. God would be disappointed to see the students looking so dirty and see this as disrespectful. I also made a sash and each day gave the cleanest, smartest-looking students the title ‘Girl of the Day’ and ‘Boy of the Day’.

In the activity periods, I let the students choose what they did. Some still chose reading and writing, and I encouraged them to write on anything – banana leaves became a favourite. I encouraged them to play word games and set sums for each other by writing with a stick in the mud. I let them do their homework on banana leaves or on other materials they could find.

I have been at the school for four years now and have made many changes. There are now 257 children on the role and attendance is regularly 240. They take pride in their appearance and arrive at school ready to learn. I have shown that all students have the ability to learn, once you have managed to motivate them.

Building relationships with the families has been important, but I think the thing that made the greatest difference was changing the curriculum to make it more interesting for the students, even though it meant less time for reading and writing. This gave them the incentive to come to school and to stay all day. As they began to make progress, they began to see that reading, writing and number could be interesting and relevant to their lives.

Activity: Identifying leadership qualities

Reread Table 1, which lists the qualities of a good leader.

With a friend or colleague, analyse Case Study 1 and identify examples of the qualities that Mrs Aparajeeta displayed. Write these in your Learning Diary, or use a highlighter pen or a pencil to underline key phrases.

Discussion

Mrs Aparajeeta set about finding out why her students were not in school by looking at the bigger picture and following her instincts. She showed resilience by not accepting that students did not attend, and set about finding ways to identify the problems and find solutions by working with parents, talking to students and reorganising the day. She improved attendance over time rather than expecting a quick result. She has a strong commitment to her students but understands the financial factors that inhibit their attendance.

Having attempted Activity 2, you might also want to look at videos of school leaders to analyse how far they display the qualities of a good leader in what they talk about.

3 Conducting a needs analysis

Table 1 suggests that a school leader needs not only personal qualities to be effective but also a range of competencies (see Resource 2). It is unlikely that you will be equally talented or accomplished in all areas. It is also important to remember that, like your teachers and students, your knowledge and skills are evolving and developing over time to meet new challenges and become more expert.

Activity 3: Conducting a needs analysis

Complete the table in Resource 2 in order to identify the aspects of the school leader role that you feel you do well and those that you need to develop – the areas you might learn more about.

First, rate yourself as ‘highly competent’, ‘adequately competent’ or ‘barely competent’. You undoubtedly have a lot of knowledge already, but you can always expand or refine your skills and abilities in the spirit of lifelong learning. Completing this table will help you to analyse your needs and development priorities to become a more effective and enabling leader.

You might want to share this process with a colleague to discuss which needs you are prioritising and discuss their needs with them. A school leader can be quite isolated, so developing a peer-mentoring relationship can be mutually beneficial. Read Case Study 2 to see how two school leaders helped each other to look at their needs.

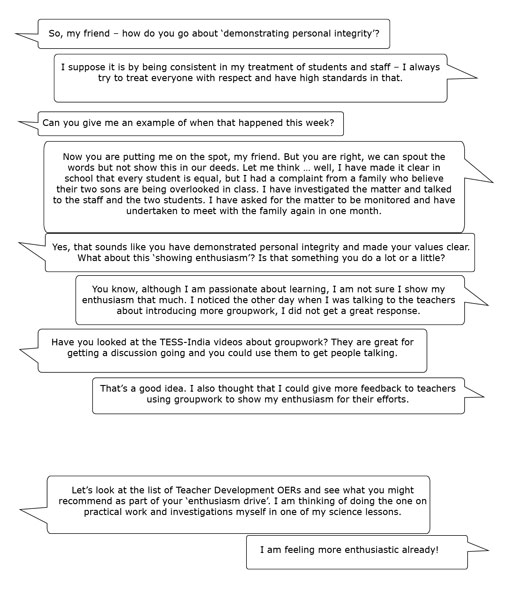

Case Study 2: Mr Kapur and Ms Agarwal discuss their needs

Mr Kapur and Ms Agarwal met recently on a training course and found that they had a lot of ideas in common. They arranged to meet every month to support each other, and decided to do Activity 3 together, helping each other to find examples and probing each other with questions. Read their conversation about the qualities of ‘modelling behaviour’.

4 Creating a Learning Plan

Having identified your professional development needs, you can now make a Learning Plan to address these needs. Resource 3 provides a list of the TESS-India School Leadership OERs.

A good one to start with (after this unit) is Transforming teaching-learning process: leading improvements in teaching and learning in the elementary school, which focuses on the core pedagogy of the TESS-India project and will give you the chance to explore the other resources that are available. All of the materials are ‘Open Educational Resources’, which means that they are free – you can make copies of them and you can adapt them to suit your context.

Activity 4: Your Learning Plan through the TESS-India OERs

Follow these steps to create a Learning Plan for yourself using the TESS-India School Leadership OERs:

- Look at the titles of the School Leadership OERs in Resource 3 and explore what each OER covers. Look at the way that the units are grouped – for example, there are three units related to developing your teachers.

- Identify three units that you would like to study. Make a note of the order in which you will study them in your Learning Diary.

- Take a more detailed look at your chosen units and decide how long you need to spend on each one.

- Make a plan for the term. Consider your work priorities, the timing of any courses you will be attending and any commitments that you have to other projects or initiatives.

Use Resource 4 to record your Learning Plan. Display it in a prominent place and refer to it each week.

Lastly, decide how you will access the materials (online or offline, or printouts) and think about anyone you might work with to extend and consolidate your learning.

5 Enacting your Learning Plan – the school leader as enabler

The single most important factor that impacts on changing teaching and learning in a school is you as a school leader – that is, your qualities and your competences. Unless you enable teachers to experiment and depart from their traditional teaching methods, there will be no change in student learning.

You enable your teachers by being a lifelong learner yourself – by applying your learning to innovate and solve issues at your school. Teachers need your encouragement to change. You can provide opportunities for and guidance to teachers by:

- trying out new ideas or practices

- giving feedback to teachers

- sharing and reflecting on the positives in their classrooms

- discussing what could be done differently to improve things.

The next case study highlights the importance of listening to your teachers and developing a collegial approach to leadership – enabling means working with and alongside your teachers, so that there is dialogue and to ensure that you learn from them.

Being an enabler is therefore about creating the conditions for active, participatory learning to take place for everyone in your school.

Case Study 3: Seeing the school in a new light

This is a record of an interview with a school leader who had recently attended a course at the local District Institute for Education and Training (DIET) for elementary school leaders. His school was doing well, and attendance had greatly improved since he had become the school leader. He was keen talk to the district education officer about the improved attendance, but started to realise that there were other important matters to attend to at his school.

On the course we were introduced to the TESS-India OERs on school self-review and development planning [Perspective on leadership: leading the school’s self-review and Perspective on leadership: school development plan]. I was looking forward to the breaks so that I could share my good news about our improved attendance with colleagues.

As we worked through the unit on self-review, I felt pleased – many things in my school are going well. But then the trainer asked us some questions about the teachers in our school, and what they thought about the school. I have three teachers but I realised that I don’t know what they think about any of the changes I have made; they have done what I have asked them to do without challenging me.

I desperately need another teacher for the youngest students, as we have to double up classes. At lunchtime, the district education officer explained that he had not managed to find anyone yet. He said that two people he had asked had requested not to be moved, because they thought that being in my school would be very hard work. In fact, he also revealed that one of teachers had approached him and asked if they could be moved to a different school. I was very surprised and disappointed.

As we moved on to development planning, I began to realise that I have been behaving a bit like a dictator. I have made many decisions about how to improve the school and implemented many changes, but I have not involved my teachers in any discussions, sought their ideas or showed that I value their experience. No wonder some of them are feeling under stress!

I realised that although the students like coming to school, I need to look after the teachers better. I went back to school and resolved to be more collegial and more supportive of the teachers. At the next staff meeting, instead of doing all the usual administrative tasks I asked them to tell me what we do well as a school. I was surprised that they mentioned such things as female students speaking up in class or that the older students are kind to the younger ones, rather than citing results and attendance. I had not really thought about these social dimensions.

Then we discussed things that could be improved, but I sensed that people were wary of being critical. I decided to ask the teachers to work together to come up with a list and said that I would not be cross if they criticised what I had done. I then made an appointment to talk to each teacher individually so that I could hear about the aspects of their work that were important to them and learn more about them as individuals. After a while the conversations between us became more open and honest, and I learned a great deal about what we could do together to change the school for the better in small steps.

Pause for thought Reflect on this case study. Do you think your teachers like working in your school? Do they feel valued, supported and reflected? |

6 Focusing on your teachers

Your attitude to your own learning will directly impact on the attitude of your teachers to their professional development. Seeing your growth in skills and readiness to change will encourage them to change and grow themselves. Your greatest resource is your teachers, and you need to provide the opportunity for them to become the best teachers they can possibly be. You need to expect and hope that they will become better teachers than you!

You might like to look at some videos of school leaders talking about leading teachers.

The TESS-India Teacher Development OERs are tools for you to help your teachers to learn new approaches and try out ideas for different ways of teaching. They position the teacher as ‘learner’, recognising that they will develop their competence in the tools and practices of the profession through actively engaging with the process of teaching and learning, and working collaboratively with colleagues.

Learning to be a teacher is a complex and a lifelong process. Various frameworks for conceptualising teacher learning and development have been suggested, but one that is particularly helpful identifies six areas of knowledge of an accomplished teacher (Shulman and Shulman, 2007):

- vision

- motivation

- understanding

- practice

- reflection

- community.

These are explored in Table 2.

| Feature | Comment |

|---|---|

| Vision | Good teachers should have a clear vision of what they are trying to achieve, underpinned by a set of beliefs about learners, knowledge and learning. They should be willing to reflect on and adapt their vision in the light of experience. |

| Motivation | Good teachers should be motivated to improve and develop. |

| Understanding | Good teachers need to know what to do and how to do it. They need to know the subjects that they have to teach and how to teach effectively. |

| Practice | Good teachers recognise that practice is complex and develops over time. They know how to enact the theories that they have learnt in the classroom. Good teachers will learn from the experience of trying different approaches. |

| Reflection | Good teachers reflect on what they are doing and learn from experience. Without reflection, teachers lack the capacity to change. |

| Community | Good teachers recognise that they are part of a community that shares the same objectives and values, and will seek support from and provide support for the community. |

Pause for thought

|

The TESS-India OERs support all these areas of teacher learning. The OERs challenge underlying assumptions and motivate teachers to try new approaches in their classroom. As a school leader, you are in a position to support your teachers by providing encouragement and creating opportunities for them to work together.

7 Summary

Recent changes in education may have placed more responsibility on Indian school leaders, but they have also created the opportunity for you to make a real difference in your school and bring your influence to bear on the learning outcomes for students. You are in a profession that is changing and you are being asked to demonstrate qualities and competences that bring about change in your school. The TESS-India School Leadership OERs can help you meet this challenge, especially in persuading teachers in your school to do things differently and adopt the new approaches that are directed by national policy in the NCF 2005 and the NCFTE 2009.

This unit has focused on the importance of you being an active learner and modelling a solution-based approach to filling gaps in your knowledge and competences. As you worked through the unit, you formed a Learning Plan using the TESS-India School Leadership OERs. You should work through this plan, monitoring your own progress and learning and sharing it with colleagues where appropriate.

Resources

Resource 1: Summary of TESS-India resources

School Leadership OERs (for you)

There are 20 OERs designed for school leaders (headteachers, principals and deputies, and those aspiring to these roles). These OERs support the school leaders in different aspects of their role, including the processes and systems that are necessary to lead a school through change and improvement. They are also designed to support leaders in enabling real changes to take place in learning and teaching, and for schools to become more focused in delivering learning in an effective, collaborative manner. These are listed in Resource 3.

Key resources

The TESS-India OERs are supported by a set of ten key resources. These key resources, which apply to all subjects and levels, offer you and your teachers further practical guidance on key practices in the pedagogy of the TESS-India OERs. They include ways of organising students, learning activities and teacher–student and student–student interactions. These key resources are incorporated into the OERs as appropriate (as resources) and are also available as individual documents for teacher-educators or school leaders to use in training and other contexts.

Audio-visual material

There is also a set of video clips that match the themes of the key resources, illustrating core participatory classroom techniques. These clips show teachers and students using participatory practices in a range of Indian classrooms and include a commentary to guide the viewer to notice particular actions and behaviours. The video clips are shot in Hindi classrooms and the audio is translated for different states. Links to these video clips are inserted into the OERs at appropriate points marked by a video icon, ![]() , and are available to users online. It is possible for users to download the video clips for use on tablets, PCs, DVDs and mobile phones using SD cards.

, and are available to users online. It is possible for users to download the video clips for use on tablets, PCs, DVDs and mobile phones using SD cards.

Teacher Development OERs (for your teachers)

There are 60 elementary OERs in four subject areas: 15 each in Language and Literacy, Elementary English, Elementary Maths, and Elementary Science. These OERs are for teachers and teacher educators, and provide practical ideas for teachers to use in their classrooms.

Resource 2: Leadership competencies audit

| Leadership competencies | How do you rate yourself? (Tick one column) | In what situation did you last do this? | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Highly competent | Adequately competent | Barely competent | |||

| Working with others | Supporting others |

| |||

| Recognising individual efforts |

| ||||

| Promoting other people’s self-esteem |

| ||||

| Developing others by providing opportunities for development and reflection |

| ||||

| Minimising anxiety |

| ||||

| Being a reflective and empathetic listener | Seeking to understand before making judgements |

| |||

| Listening to individual ideas and problems |

| ||||

| Actively encouraging feedback |

| ||||

| Empowering others | Empowering others to make decisions and take responsibility |

| |||

| Modelling behaviour | Demonstrating personal integrity | ||||

| Modelling the attitudes and values that you wish to promote |

| ||||

| Showing enthusiasm |

| ||||

| Being proactive in making decisions | Providing direction and a clear vision |

| |||

| Making decisions |

| ||||

| Promoting understanding of key issues |

| ||||

| Managing change | Encouraging new ways of doing things | ||||

| Anticipating possible future challenges | |||||

| Treating mistakes as learning opportunities | |||||

| Encouraging teamwork | Encouraging and promoting teamwork by involving all | ||||

Resource 3: School Leadership learning outcomes

| NCSL key area | OER title | Learning outcomes |

|---|---|---|

| Orientation | The elementary school leader as enabler |

|

| The secondary school leader as enabler |

| |

| Perspective leadership | Building a shared vision for your school |

|

| Leading the school’s self-review |

| |

| Leading the school development plan |

| |

| Perspective on leadership | Using data on diversity to improve your school |

|

| Planning and leading change in your school |

| |

| Implementing change in your school |

| |

| Managing and developing yourself | Managing and developing yourself |

|

| Transforming teaching-learning process | Leading improvements in teaching and learning in the elementary school |

|

| Transforming teaching-learning process | Leading improvements in teaching and learning in the secondary school |

|

| Leading assessment in your school |

| |

| Supporting teachers to raise performance |

| |

| Leading teachers’ professional development |

| |

| Mentoring and coaching |

| |

| Transforming teaching-learning process | Developing an effective learning culture in your school |

|

| Promoting inclusion in your school |

| |

| Managing resources for effective student learning |

| |

| Leading the use of technology in your school |

| |

| Leading partnerships | Engaging with parents and the wider school community |

|

Resource 4: Your Learning Plan

| Priorities and commitments for the next academic year (including courses, initiatives you are involved in and things that have to be achieved, such as a school self-review or writing an SDP) |

|---|

|

| OERs to study in the next three months |

1. 2. 3. |

| OERs to study within the next year |

1. 2. 3. 4. 5. |

| How will I make time to study and learn? |

|

| What might get in the way of my plan? |

|---|

|

| How I will avoid any sabotage of my plan? |

|

| How I will access the units for myself? |

|

| What arrangements will I make to find a study partner or mentor to help me with my learning and apply it to my context? How often will I talk to them? |

|

| How will I evaluate my learning? |

|

Additional resources

- National Centre for School Leadership: http://www.nuepa.org/ ncsl.html

References

Acknowledgements

Except for third party materials and otherwise stated below, this content is made available under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike licence (http://creativecommons.org/ licenses/ by-sa/ 3.0/). The material acknowledged below is Proprietary and used under licence for this project, and not subject to the Creative Commons Licence. This means that this material may only be used unadapted within the TESS-India project and not in any subsequent OER versions. This includes the use of the TESS-India, OU and UKAID logos.

Grateful acknowledgement is made to the following sources for permission to reproduce the material in this unit:

Table 1: adapted from: Gardner, H. (1997) Leading Minds: An Autonomy of Leadership. London: HarperCollins.

Table 2: adapted from Shulman, L.S. and Shulman, J.H. (2007) ‘How and what teachers learn: a shifting perspective’, Journal of Curriculum Studies, vol. 36, no. 2, pp. 257–71.

Table R2.1: adapted from: MacBeath, J. and Myers, K. (1999) Effective School Leaders: How to Evaluate and Improve Your Practice. Harlow: Pearson.

Every effort has been made to contact copyright owners. If any have been inadvertently overlooked the publishers will be pleased to make the necessary arrangements at the first opportunity.

Video (including video stills): thanks are extended to the teacher educators, headteachers, teachers and students across India who worked with The Open University in the productions.