Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Wednesday, 4 February 2026, 9:34 PM

TI-AIE: Perspective on leadership: planning and leading change in your school

What this unit is about

Change in its various forms is a common occurrence in educational systems and within schools. The drivers may be external or internal, or a combination of both. Change may be imposed on you or started by you. In most cases the ultimate aim is to move from a current state to a more desirable future state. Within a school context, this ultimately relates to improving student learning, either through direct changes to teaching and learning or through improving the effectiveness of school structures and systems to support learning.

In this unit you will consider what change means in your school or educational setting and consider some of the drivers of educational change. You will then move on to look at different leadership approaches such as collaborative, distributed, democratic and transformational leadership. You will link these different approaches and perspectives to educational leadership.

Motivation and trust are considered to be important levers for change. Therefore, you will spend some time looking at how best you can motivate yourself and others as you prepare to lead change. You will reflect on your role as a leader and consider how some of the issues presented in this unit can help you improve on your current practice.

Learning Diary

During your work on this unit you will be asked to make notes in your Learning Diary, a book or folder where you collect together your thoughts and plans in one place. Perhaps you have already started one.

You may be working through this unit alone, but you will learn much more if you are able to discuss your learning with another school leader. This could be a colleague with whom you already collaborate, or someone with whom you can build a new relationship. It could be done in an organised way or on a more informal basis. The notes you make in your Learning Diary will be useful for these kinds of meetings, while also mapping your longer-term learning and development.

What school leaders can learn in this unit

- To identify external and internal drivers for change within schools.

- To identify challenges to implementing change.

- To take necessary steps in planning and leading change in your school.

- To identify educational leadership approaches and relate these to your approach.

- To lead by example, inspiring and motivating others through a change project.

1 Introduction to change

Change can be a challenging process for both the leader(s) and participant(s) involved, as people may be worried about the consequences. In many educational systems, it is policymakers who often initiate many school-related changes; these are external drivers. However, there are also other instances where you as a leader, with your teachers, have also made small or medium-sized changes to your school in response to the needs and interests of your students and perhaps the community; these are internal drivers.

Activity 1: Drivers of change

As a starting point, think about changes that have happened recently in your school. Did they feel imposed from the outside or did they come about from the school community? They may be substantial changes to the curriculum or exams set by national or state bodies, or they may be smaller changes in your school that were initiated to make the day more productive for students.

List five external factors and five internal factors that you feel have been the drivers of change in your school or district.

Discussion

The internal drivers you identify will depend heavily on the context you are working in and the resources available to you as a school leader. Even if your school has minimal resources and large classes, you can still initiate and lead considerable changes that will have a positive impact on learning, for example including more children with a disability or having more female students in the upper grades.

This activity may have prompted you to think about the kinds of changes you would like to realise in your school. They may be to do with introducing a more student-centred approach, facilitating more activity-based learning, valuing and respecting every child and their uniqueness, or organising assessment for learning rather than for exams/tests.

Table 1 shows examples of recent external drivers at elementary and secondary levels. Sometimes these are widely anticipated and there have been preparations to accommodate them; at other times they are more sudden. Some require immediate action; for others the change will be more gradual.

| Elementary | Secondary |

|---|---|

National Curriculum Framework (NCF) Right to Education Act 2009 (RtE) Sarva Shiksha Abhiyan (SSA) Mid Day Meal Scheme Mahila Samakhya Programme Scheme to Provide Quality Education in Madrasas | Rashtriya Madhyamik Shiksha Abhiyan (RMSA) Model Schools Scheme Girls’ Hostel Scheme ICT @ Schools Inclusive Education of the Disabled at Secondary Stage Scheme of Vocational Education National Means-cum-Merit Scholarship Scheme National Incentive to Girls Appointment of Language Teachers |

2 Dealing with challenges

School leaders and teachers often face challenges when making changes. Case Studies 1 and 2 are examples of how teachers and others have set out to make a difference by initiating a change.

Case Study 1: Additional activities to boost attendance

Theme: Organisation of the school timetable/day.

Teacher: Mrs Kapur.

Context: Public school with 550 students. It is predominantly Muslim and is located in a medium-sized town.

Problem statement: Mrs Kapur noticed that the short length of the school day and pressure to complete the curriculum meant that little time was available for students to participate in creative or sporting activities. These activities are important for the students’ overall development. In addition, she was concerned about student attendance and wanted a means of motivating them to be at school.

The change: The change that Mrs Kapur initiated to address this challenge involved lengthening the school day. By adding an extra half an hour at the end of each school day, Mrs Kapur was able to create time and space for unique activities without compromising on the school’s focus on the core curriculum. Activities such as sports (karate), games including carrom and chess, and library time are rotated. Students do not know which activity they will participate in at the end of each day, which adds an element of surprise and generates additional interest in coming to school. The value of the innovation is its contribution to the holistic development of the child while increasing both the students’ enjoyment of school and the time available for learning.

Why this is interesting: It seeks to address the current situation where an Indian child typically spends only four hours at school, compared to six to eight hours that students in developed countries spend at school. In addition, it recognises the need to create an enjoyable environment at school to improve attendance.

Potential implementation challenges: The school management committee (SMC) may need convincing. There may be significant resource challenges to providing extra-curricular activities. Schools should be careful to offer activities that students are actually interested in and to ensure that girls and boys benefit equally.

Impact so far (according to teacher): Mrs Kapur has seen attendance increase and discipline improve markedly. Students are now excited to be in school.

Case Study 2: Health check-ups to safeguard learning

Theme: External factors impacting on education (e.g. nutrition or health).

Teacher: Mr Chakrakodi.

Context: Public school located in a very deprived area of East Delhi.

Problem statement: Mr Chakrakodi knew that many of his students had no access to healthcare and that they lived in environments that were unhygienic. This resulted in sick students either attending school and spreading disease, or being consistently absent.

The change: The change designed to overcome this problem involved a triple-pronged health scheme. By brokering relationships with local medical professionals, Mr Chakrakodi ensured free medical check-ups for students every two months and a free eyesight testing service. Finally, Mr Chakrakodi found a sponsor to provide healthy lunches specifically to younger students, who need vitamins for healthy growth. The value of this change is that students are not only provided with healthcare and eye tests, but that they are taught how to live more healthily.

Why this is interesting: It takes a preventative approach to reducing student absence, which is so damaging for learning.

Potential implementation challenges: In order to be successful at scale, doctors and nurses would need to be incentivised to provide healthcare in schools.

Impact so far (according to teacher): Mr Chakrakodi reports that student attendance has improved, concentration has increased markedly and there has been buy-in from parents, who have engaged with the school in appreciation for the health services provided. One of the bi-monthly check-ups successfully diagnosed a student with a serious liver infection, which, as a result, was treated in time. Mr Chakrakodi has now expanded the free eye care service into the community.

Figure 1 Strategies will improve student learning.

Although your school may not face the same issues, it is worth thinking about some of the challenges that your staff and students face, and to begin to think about how you, as a school leader, can put strategies in place to alleviate them and improve student learning. You should also think about how you will approach these changes, and how you will work with staff, students and the community to ensure that whatever you put in place is sustained and has real impact on the lives and learning of your students.

3 How change happens

Several views have been presented on how change comes about in our schools and educational settings. One such argument is the notion of internally versus externally initiated change. By internally initiated change we consider all students, teachers and administration staff as potential change agents who, through their work, are able to initiate and implement change (mainly owing to the need to improve on quality and standards). This is often described as the voluntarist view, because the emphasis is on how the voluntary (or self-initiated) actions of leaders and other change agents bring about change within the school.

Another view is that most educational change is externally initiated. This is characterised by pressures from education authorities as new policies are introduced. This is often referred to as the deterministic view, because it sees leaders and their staff as targets of a change that is determined by external forces (economics, technology, globalisation, culture shift, etc.). Many teachers and school leaders say that they often experience this kind of change where the requirement to change is demanded or enforced.

Change in the school context refers to any form of change that takes place in the school, whether it is deliberate action by staff or students to change the status quo, or is a state or national initiative. The change could be proactive (a deliberate, self-initiated action) or reactive (responding to a stimulus).

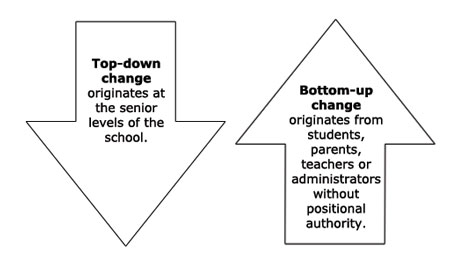

Regardless of whether it is internally or externally driven, there are two ways of looking at how change is actually initiated within a school (Figure 2).

Figure 2 Top-down and bottom-up change.

Top-down change can be seen as relatively easy and straightforward to put into practice across the school, provided it is negotiated and agreed by staff and SMC members – which is not always the case. It usually takes a school-wide approach, and so has the advantage of promoting a consistent, systematic approach to the change at hand. Top-down change usually involves some degree of consultation with those implementing the change; however, particularly in times of crisis, top-down change can be imposed in a directive and coercive way without staff consultation. This may have severe consequences for motivation and morale, but if organisational survival is at stake, school staff may well accept the need for rapid and drastic action without a consultation process.

Bottom-up change, on the other hand, has the advantage of being designed by the school community itself. This is mandated by the RtE, wherein SMCs are to develop, implement and monitor plans, and then promote it across the school. Bottom-up change may also be suggested by anyone in the school, but then implemented by senior staff who have the authority to influence and drive it through. However, it often requires a high degree of negotiation, and a school community may not readily agree on a change; so it raises other challenging issues. For this reason, bottom-up change is sometimes considered to be unpredictable and it takes time for it to be adopted across the organisation.

Figure 3 Listening to students’ ideas.

To minimise problems in any change initiative, some school leaders implement their change in one area of the school as a pilot scheme to try out new ways of working, assess problems and issues that arise, and make any necessary adjustments before rolling it out across the whole school. This means that any major weaknesses can be sorted before introducing the change on a larger scale.

Activity 2: Changes in your school

Spend some time thinking of three significant changes that have taken place in your school in the last year or two. They might be large or small changes, but they will have meant that people had to change their priorities, behaviours or processes. In your Learning Diary, make notes related to the following questions:

- What was the driver or initiator for each change?

- How did you and others respond to that driver?

- What were the challenges of implementing the change?

- How did you and your colleagues cope with the change?

- What has been the impact of the change on student learning?

Discussion

Educational change initiatives can embrace a broad range of issues: classroom practice, school-level change or larger-scale transformation at state or national level. Your own response will vary from that of other school leaders, because change affects everyone differently. Some colleagues may have a wealth of experience of change; others may be witnessing it for the first time. While some may be anxious about change and their role, others may seize the opportunity to steer and influence.

The examples in Case Studies 1 and 2 are typical of bottom-up change. Although external stakeholders were involved in the success story reported at New Shishu Public School, the change was started by school leaders who recognised and addressed a local problem.

It is preferable to get buy-in or agreement from all stakeholders in any change initiative. However, you may find yourself in a situation where not everyone shares your view of the future. For this reason, your approach to any change is crucial. You will consider some of these issues in Section 6.

There are therefore three important things to bear in mind when leading or managing change:

- There is an element of uncertainty: no one knows what the future holds, but reasonable plans can be put in place to reach the future goal.

- Change requires leadership: someone, or a group of people, who may not necessarily be a leader by job description but who takes control and provides direction throughout the change period.

- Change has an emotional impact: it affects people differently and they react in different ways – some negative, some positive.

But is change always good? Some may argue that minimal change is necessary for sustainability, and would therefore consider stability and change as opposites. One could also argue that stability and change are interdependent, as they are both necessary in a world that is changing at great speed. Without change, an organisation could become obsolete. Schools may find that change is necessary to respond to external changes such as migration, new technologies, poverty, gender imbalance, employment skills deficits, etc.

In a changing external environment, internal change is required for the organisation to appear to stay the same and maintain stability in its community and wider context. For example, a school with an increasing migrant population may have to change some of its practices and processes to accommodate the different cultures that constitute the student population. If it does not change, segregation, intimidation and tension among students and staff could arise.

In the sections that follow, you will look at school-level change and begin to consider how you, as a school leader, can work with your staff to bring about change. You will also consider some ways in which you can overcome barriers to change and foster an environment that allows others to try new approaches.

4 Planning and leading change

Very often we describe the process of organisational change in a linear fashion, where one stage follows another sequentially. In reality, it is anything but linear. The process is usually described in phases that are not discrete: they are a set of overlapping functions that are constantly reviewed and adjusted during the change process. A detailed analysis of the examples described in Case Studies 1 and 2 would probably reveal changes to the original plan in response to the challenges that were faced.

Decisions about what to change do not always present a clear-cut answer. Focusing on classroom practice, a leading educational theorist Fullan (2007) identified at least three dimensions in implementing a new educational programme. These can include:

- new or reused teaching and learning resources (including information and communication technology)

- new teaching approaches or activities

- alteration of beliefs (e.g. pedagogical assumptions and theories).

These three broad categories are not mutually exclusive: educational change requires a combination of all of them. Regardless of how small the change initiative is in the school environment, your intended outcome is likely to impact both the internal (school) and external context (the immediate community, state, government and other agencies).

As a school leader, the following key factors need to be carefully considered in your planning:

- You should be ready to explain your rationale for the need for change clearly and concisely to others.

- You need to be clear about what you intend to do and the outcomes. It is important that you are clear about roles and responsibilities, and exactly what success will look like.

- Any unnecessary complexity in the process should be removed.

- You must ensure that the planned change is practical and achievable. You may need to reduce the size, scale or timeframe for the change in order for it to succeed, or split the change idea into smaller tasks.

- Evaluate the impact of the change – what has changed and by how much?

5 Leadership approaches

The debate about which approaches are most suitable in leading educational change continues. Academics and practitioners have presented several views, some of which we discuss in this section. It is important that you, as a school leader, should not do all the work yourself. Apart from getting physically exhausted, you are likely to get a better reaction when everyone plays a part. While some people may be assigned specific duties and responsibilities, others may only take part in decision making – but the underlying principle is maximum engagement to maximise participation.

When change is imposed, directions are often given on planning, implementation and the timeframe. You will need to translate this into a plan for your school with clearly defined outcomes. It is useful to have a clear communication process and let everyone know about the part they are expected to play. Although a well-planned change does not guarantee success, it does make it easier to streamline the processes and to identify potential barriers.

Case Study 3: Mr Rawool struggles to make changes

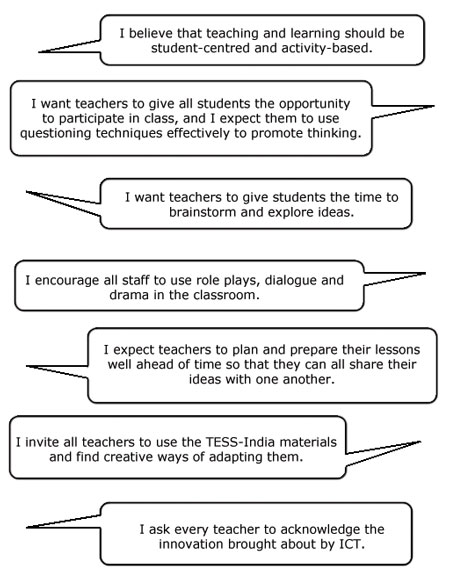

Mr Rawool is school leader of a public school in East Delhi. His passion from childhood has been to help others, which was his motivation to train as a teacher. He describes his approach like this:

Since he became school leader two years ago, Mr Rawool has faced challenges in dealing with some of his staff. Although he is confident in his ability to teach and support new teachers to deliver productive lessons, he has had some difficulty dealing with a number of very experienced teachers.

Mr Rawool’s efforts are welcomed by most of the teachers, but he is not making any significant progress with three of his most experienced staff. Some of his principles are unfamiliar to them, and they claim that their methods are more appropriate because they believe that the students learn best when they listen to the teacher lecturing.

Activity 3: Advice to Mr Rawool

What advice would you give to Mr Rawool? How would you approach this change process and engage the three experienced staff? Note down your ideas in your Learning Diary.

Discussion

Typical barriers to successful change include lack of commitment in implementation, resistance from some participants, inadequate resourcing and unforeseen changes in the environment that the change is situated in. In the case of Mr Rawool’s staff, we can deduce that the key barriers to change are long-standing attitudes and practices that are believed to work best. Your advice probably involved engaging with the three teachers either individually or together. It may have involved a ‘whole team’ approach where the staff group together ‘sign up’ to his approach. It is always important to recognise your teachers’ achievements and experience as any new ideas or approaches need to build on these. As you read through the next section, consider how far your suggested approach fits with the leadership styles outlined.

Leadership styles

Collaborative leadership involves two essential components: the team and consensus. Decisions are taken based on a general consensus among staff, so there will be space made for group discussions or consultations to allow everyone’s view to be heard. Collaborative leadership is seen as a positive approach to leading and managing change, as it brings people together and builds shared understanding. Some critics argue that the pace of change sometimes does not allow enough time for consensus building and therefore question the practicalities of this approach.

Another approach that has dominated educational leadership discourse in recent years is distributed leadership. For Gronn (2003), the essence of distributed leadership is that it creates a sense of responsibility that is spread among several people within the school. Distributed leadership allows schools to cope with complex or urgent change by drawing a wider range of staff into the leadership task.

There are many different points of view about this approach, especially around issues of boundaries and accountability. Harris (2008) maintains that distributed leadership is still firmly controlled by senior leaders and suggests that there is a blurred distinction between distributed leadership and delegation. This view is shared by Hartley (2010), who argues that teachers and students have very limited influence on the direction of school strategy, so distributed leadership is more a way of accomplishing predefined organisational goals through tasks and targets set by senior leaders. Where traditional hierarchies define roles and responsibilities in a school, there can be unease and mistrust when authority and responsibility is distributed in this manner.

Essentially, democratic leadership in schools is about creating an environment that supports participation, shared values, openness, flexibility and compassion. Furman and Starratt, in their article ‘Leadership for democratic community in schools’ (2002, p. 118), asserted that democratic school leadership requires the ability to ‘listen, understand, empathise, negotiate, speak, debate and resolve conflicts in a spirit of interdependence and working for the common good’. A democratic school leader is therefore likely to be approachable and ready to take on others’ ideas and solutions.

Furman and Starratt continued by saying that, in democratic schools, leadership is vested in the stakeholders and their expertise rather than in bureaucracy. This involves engaging stakeholders in decision making and establishing conditions that foster consultation, active cooperation, respect and a sense of community for the common good. Critics question whether this style of leadership really does count everyone’s vote in reaching decisions, arguing that final decisions are still made by senior leaders.

Transformational leadership identifies new goals that will drive changes in practice and persuades others that they can achieve more than they thought possible. It places strong emphasis on the central role of the leader. The leader has to be convincing and generate enthusiasm in others, so needs to:

- have a vision of how the future organisation will look

- acknowledge that colleagues must share that vision if it is to be achieved

- work hard to persuade colleagues that the vision is worth pursuing

- work collaboratively towards achieving the vision.

Activity 4: The leader as motivator

Reflect on some of the changes you have experienced as a teacher or a school leader. It might be a good experience or you may have had reservations about the changes (for example, the introduction of activity-based learning in your school, or implementing revised guidance on multi-level classes). Describe in your Learning Diary how you:

- were motivated by the leader

- motivated others as a leader

- kept yourself motivated as the leader.

Discussion

All leaders will also have to deal with their own feelings about change, and an awareness of how change commonly affects people will help with this. During a change period, it is a leader’s job to ensure that they maintain a positive attitude both individually and in the school community. It is essential that school leaders do all they can to create a working environment where everyone is able to make sense of what is going on and cope with the changes. If change is imposed without sufficient discussion, consultation and explanation, most people will have difficulty in reacting positively.

Case Study 4: Ms Patel describes her worries as a school leader

As the school leader, Ms Patel was fairly happy with the progress made by the school in recent months, but she remained worried about certain issues. She distinguished between her role as a manager and her role as a leader, to describe her worries.

As a manager, Ms Patel was satisfied that the school had the necessary teams to handle issues of governance, finances, physical resources, staff development, communication and school development. In addition, there were various teams involved in curriculum planning and monitoring, managing assessment, and supporting learners with specific learning needs. She organised attendance at all the training, workshops and discussion forums organised by the state authority and DIET. She ensured that teachers who attended training and workshops reported back on what they had learnt at the next staff meeting and wrote a report to the SMC.

As a leader, Ms Patel remained concerned that although subject teams were well established, they met irregularly, kept inaccurate minutes and did not follow up on action points. Ms Patel observed that nothing much changed following the team meetings and that group discussions following training were superficial and infrequent, with people having little time or energy to be enthusiastic about them. Reflection on practice was still very limited and did not appear to change practice.

Ms Patel’s staff seemed willing to cooperate and would normally try to implement changes that she suggested. However, they did not really engage with the issues, suggest new things or implement change themselves. In fact, they seemed somehow jaded, and fell into what could be described as ‘survival mode’ rather than being the impassioned innovators that she had hoped to nurture. She felt that the school needed to rediscover a sense of purpose and a passion for learning.

Activity 5: The importance of a team approach

How would you approach such a situation? Address the points below, making notes in your Learning Diary.

- How far does this case description compare with the situation in your school?

- What advice could you offer to Ms Patel to help her revitalise her school?

- Draw up an action plan for Ms Patel.

Discussion

There are no ‘right’ answers to this activity. You should think about Ms Patel’s particular situation in order to help you to engage with issues of teamwork and self-evaluation at your own school. Many schools are like this school, with the staff simply ‘going through the motions’ and drifting from day to day – conforming, rather than transforming. Fundamental to addressing the kind of staff malaise experienced by Ms Patel is the need to understand the situation that staff find themselves in. If you understand where their lack of enthusiasm comes from, perhaps you can engage with them in a more appropriate and sensitive way.

6 Overcoming barriers to change

Many people embark on change projects with good intentions, but often struggle to overcome the barriers and setbacks that occur along the way. Some leaders get distracted by petty disagreements and emotional resistance, and accept failure rather than work hard to overcome these barriers. So the question is: Is failure more powerful than success?

Two allies for leaders in overcoming the inevitable barriers to change are trust and motivation. If a leader has the trust of their school community, their belief in the positive outcomes of a change will help to overcome barriers. Motivation to change not only has to be built in the first place, but also needs to be maintained over the period of change and continued to sustain the change.

Trust

Trust is a fundamental element of any relationship, including that between a leader and their followers. Trust is the glue that holds relationships together and is therefore vital in day-to-day school life – particularly when you are introducing something new. When trust is absent, a leader may find that their followers turn to someone else for guidance and direction. As a school leader, you earn and build trust among the school community through your work and leadership – much is based on the soundness of your judgement and consistency of your practice. It can take a long time to establish but only moments to destroy. Lost trust is very difficult to restore.

Trust is two-way: school leaders need to be able to trust their colleagues to conduct their duties to the highest possible standards and delegate tasks in full confidence that the job will be carried out. On the other side, teachers and stakeholders (parents, students and the wider community) have to be able to trust school leaders to lead the school in the right direction. They have to be certain that the school leader has the best interests of the students, staff and school at the forefront of their decision making.

Motivation

In order to make a change, people need to be motivated and to sustain their motivation. In the initial stages, change can arouse curiosity and excitement at what may be about to happen. This will carry some people along in the early stages of change, but may not last long enough to bring about any real benefits. On the other hand, change can also incite fear, confusion and tension, which can lead to resistance. As the change process continues, motivation may drop as fatigue sets in and performances decline.

Emotions can run high at times of change and leave people feeling vulnerable and unmotivated. This can lead to attempts to sabotage – whether consciously or subconsciously – the change process. These emotions include aggression, stress or anxiety. Any leader planning a change must be aware of these emotions; and allow time and resources in the plans for the necessary communication, extra time to do the work, and offer training that will help people to deal with both their emotions and the change. This will avoid some of the problems that result from people’s psychological reactions to change. Distressed or unmotivated colleagues will not change easily or effectively.

Activity 6: Promoters and inhibitors of change

Consider your school and what happens there to promote or inhibit change. Make notes in your Learning Diary of four factors that help change to take root in your school. Why do you say so? Now identify four factors that prevent change in your school and describe your possible solutions.

Discussion

Here are some examples of promoters that may vary from your schools and leadership practice:

- everyone is allowed to try new things

- the staff believe in the vision of the school

- there are clear lines of communication

- the staff know and understand their roles within the change process.

Here are examples of inhibitors:

- individual or group reluctance to challenge the prevailing culture (‘we’ve always done it this way’)

- routine is disrupted

- the staff do not want ownership

- uncertainty

- fear

- possible increase in workload

- effort required (input) may not match the desired outcome (output)

- teachers and stakeholders may not have confidence in the leadership

- staff blaming students’ home background for examination failure

- personality clashes, personal agendas and fractured interpersonal relationships.

It is important to remember that not everyone opposes change for the sake of it. There is no single solution to any of the inhibitors you may have listed in Activity 6, but here are some ideas.

- Set out your objectives for the change right from the start. State clearly what you want to achieve, and why. It is useful to use more than one method. For example, you could call a team meeting and discuss future plans, and then follow this up with a written memo giving everyone at the meeting all the same details. The tone of these communications should be positive and optimistic while being reassuring.

- Explain how dangerous it can be for the school to become too complacent. Make sure that your teachers are given plenty of examples: stories of how other schools have succeeded, as well as examples of schools that are struggling because they have failed to respond to a changing environment.

- Acknowledge the risks of change but explain the consequences for not changing.

- Where change is planned internally, point out that it could happen to your school no matter what you do, and that therefore, it is better for the school to make its own changes voluntarily and in a controlled manner rather than have them imposed.

- Draw on the experiences of your staff and other stakeholders.

Activity 7: Writing a change action plan

What practical measure have you put in place in your school to ensure that you meet the requirements of a new initiative such as the RtE or CCE? Reflect on your study of this unit and think about two small changes you would like to make in your school to improve student learning and achievement. Then complete the change action plan in the resources section.

It may be useful to share your ideas with your staff and discuss your implementation timescale and any foreseeable challenges.

7 Summary

You have considered in this unit the various dimensions of leading change, including different styles of leading, such as distributed leadership, and the importance of trust and motivation in bringing people along with the change. Some leaders may focus on the benefits to those who will benefit from the change, rather than on the problems of those who will be negatively affected by the change. It is therefore important to consider the impact on everyone concerned.

You have thought about whether change is driven by external forces or is initiated within the school, and have probably come to the conclusion that leading change is not simple and does not necessarily follow a logical path. As a leader of change, you need to:

- establish a shared vision of the future that people can believe in

- motivate people and steer them through any challenges during the change process

- share responsibilities and ownership of the change

- ensure that there is resilience and action taken to overcome barriers

- support colleagues before, during and after the change.

This unit is part of the set or family of units that relate to the key area of perspective on leadership (aligned to the National College of School Leadership). You may find it useful to look next at other units in this set to build your knowledge and skills:

- Building a shared vision for your school

- Leading the school’s self-review

- Leading the school development plan

- Using data on diversity to improve your school

- Implementing change in your school.

Resources

Resource 1: Change action plan

| Name: | Date of creation: | Date of review: | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| What small change(s) do I want to implement? | Outcome(s) of this change | How I hope to achieve this | The actions I will take | The people involved | How I will know I’m successful |

| |||||

| |||||

|

References

Acknowledgements

This content is made available under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike licence (http://creativecommons.org/ licenses/ by-sa/ 3.0/), unless identified otherwise. The licence excludes the use of the TESS-India, OU and UKAID logos, which may only be used unadapted within the TESS-India project.

Every effort has been made to contact copyright owners. If any have been inadvertently overlooked the publishers will be pleased to make the necessary arrangements at the first opportunity.

Video (including video stills): thanks are extended to the teacher educators, headteachers, teachers and students across India who worked with The Open University in the productions.