Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Thursday, 5 March 2026, 3:18 AM

Adolescent and Youth Reproductive Health: 1. Introduction to Adolescent and Youth Reproductive Health (AYRH)

Study Session 1 Introduction to Adolescent and Youth Reproductive Health (AYRH)

Introduction

More than a quarter of the world’s population is between the ages of 10 and 24, with 86% living in less developed countries. These young people are tomorrow’s parents. The reproductive and sexual health decisions they make today will affect the health and wellbeing of their communities and of their countries for decades to come.

In particular, two issues have a profound impact on young people’s sexual health and reproductive lives: family planning and HIV/AIDS. Teenage girls are more likely to die from pregnancy-related health complications than older women in their 20s. Statistics indicate that one-half of all new HIV infections worldwide occur among young people aged 15 to 24.

In this study session you will learn about changes during adolescence and why it is important to deal with adolescents’ reproductive health problems. You will learn about factors affecting adolescents’ risk-taking behaviours and its consequences. You will also learn the importance of raising awareness about adolescent reproductive health rights.

Learning Outcomes for Study Session 1

When you have studied this session, you should be able to:

1.1 Define and use correctly all of the key words printed in bold. (SAQs 1.1 and 1.5)

1.2 Show that you understand that different groups of adolescents have different needs. (SAQs 1.1 and 1.5)

1.3 Briefly describe the biological and psychosocial changes during adolescence. (SAQ 1.2)

1.4 Explain why adolescents are especially vulnerable to reproductive health risks. (SAQ 1.3)

1.5 Show that you are aware of adolescent reproductive health rights and the need to provide appropriate information and services. (SAQ 1.4)

1.1 Why it is important to provide services for adolescents and young people

The World Health Organization (WHO) defines an adolescent as an individual in the 10-19 years age group and usually uses the term young person to denote those between 10 and 24 years. In this Module we will use these definitions and also the terms early adolescence (10-14), late adolescence (15-19) and post-adolescence (20-24), because they are helpful in understanding the problems and designing appropriate interventions for young people of different ages. You will explore the relevance of this classification in greater detail in Study Sessions 10 and 12 which discuss how you can promote and provide adolescent and youth-friendly reproductive services.

Adolescence is a period of transition from childhood to adulthood during which adolescents develop biologically and psychologically and move towards independence. Although we may think of adolescents as a healthy group, many die prematurely and unnecessarily through accidents, suicide, violence and pregnancy-related complications. Some of the serious conditions of adulthood (for example, sexually transmitted infections (STIs), like HIV; and tobacco use) have their roots in adolescent behaviour.

Studies show that young people are not affected equally by reproductive health problems. Orphans, young girls in rural areas, young people who are physically or mentally impaired, abused or have been abused as children and those migrating to urban areas or being trafficked are more likely to have problems.

Despite their numbers, adolescents have not traditionally been considered a health priority in many countries, including Ethiopia. While the country has been implementing major interventions to reduce child mortality and morbidity, interventions addressing the health needs of young people have been limited. Young people often have less access to information, services and resources than those who are older. Health services are rarely designed specifically to meet their needs and health workers only occasionally receive specialist training in issues pertinent to adolescent sexual health. It is perhaps not surprising therefore that there are particularly low levels of health-seeking behaviour among young people. Similarly, young people in a variety of contexts have reported that access to contraception and condoms is difficult.

The negative health consequences of adolescents can pass from one generation to the next. For example, babies born to adolescent mothers have a high risk of being underweight or stillborn. They are also likely to suffer from the same social and economic disadvantages encountered by their mothers. That is why addressing the needs of adolescents is an intergenerational investment with huge benefits to subsequent generations (see Figure 1.1).

If the nation is to address its rapid population growth, it is crucial to acknowledge the importance of the reproductive health concerns of adolescents and young people, particularly in their decisions related to avoidance of unwanted pregnancy.

1.2 Strategies for promoting the reproductive health of young people

The Government of Ethiopia has adopted policies and strategies to address some of the social, economic, educational and health problems faced by young people. Currently, national programmes are guided by a 10-year plan which is based on the ‘National Adolescent and Youth Reproductive Health Strategy 2006-2015’. Other key documents indicating government commitment include the Young People Policy issued in 2000, the Policy on HIV/AIDS launched in 1998, the Revised Family Laws amended in 2000 to protect young women’s rights, (for example against forced marriages), and the Revised Penal Code, which penalises sexual violence and many harmful traditional practices.

When developing and implementing interventions you need to take into account that while many adolescents and young people share common characteristics, their needs vary by age, sex, educational status, marital status, migration status and residence. When developing and implementing interventions you need to appreciate that you will have to work in different ways with different age groups.

An activity that is suitable for those in early adolescence (10-14 years old) may not be suitable for those in post-adolescence (20-24 years old). For instance, those in their early adolescence are more likely to be in primary schools, not yet married and hence less likely to have started sexual relationships, all of which determine the type of information and services that would be appropriate for them.

You need to give special attention to these vulnerable young adolescents (aged 10-14) and those at risk of irreversible harm to their reproductive health and rights (e.g. through forced sex, early marriage, poverty-driven exchanges of sex for gifts or money, and violence). As has already been mentioned, some groups are more vulnerable than others and it is to vulnerable individuals that you need to offer most help. In this Module you will gain an understanding of who these vulnerable individuals are and insight into their difficulties, and you will learn how you can help them.

You may have already recognised that men and women are not treated equally in your community. In general, girls and women are treated as inferior and they are given fewer privileges and less access to resources. The roles they have within your community are different to the roles given to men. Gender refers to the socially and culturally defined roles for males and females. These roles are learned over time, can change from time to time, and vary widely within and between cultures. In Study Session 6 there will be a discussion of the way that women are treated unfairly because of the way they are viewed within many communities. This gender inequality means that girls and women need your help to safeguard their sexual and reproductive health to a greater extent than do young boys and men.

In this Module you will also learn how you can help provide a group of services for young people, such as counselling, family planning, voluntary counselling and testing for sexually transmitted infections (STIs) including HIV, maternal and child health, and post-abortion care. You will learn how to involve other members of your community and how to find ways of working with them and you will recognise when you need to refer individuals for help at the next level of health facility.

1.3 Protecting adolescent sexual and reproductive health

Adolescent sexual and reproductive health refers to the physical and emotional wellbeing of adolescents and includes their ability to remain free from unwanted pregnancy, unsafe abortion, STIs (including HIV/AIDS), and all forms of sexual violence and coercion.

One of the important concerns of young people is their sexual relationships. In particular, young people need to know how they can maintain healthy personal relationships. It is important to keep in mind that sex is never 100% ‘safe’, but you can advise young people on how to make sex as safe as they possibly can. That is why you should always talk about ‘safer’ sex and not ‘safe sex’.

As a Health Extension Practitioner, you need to educate young people in what constitutes safer sex and the consequences of unsafe sexual practices. Safer sex is anything that can be done to lower the risk of STIs/HIV and pregnancy without reducing pleasure. The term reflects the idea that choices can be made and behaviours adopted to reduce or minimise risk.

Sexual activities may be defined as high risk, medium risk, low risk, or no risk based on the level of risk involved in contracting HIV or other STIs.

No risk

There are many ways to share sexual feelings that are not risky. Some of them include hugging, holding hands, massaging, rubbing against each other with clothes on, sharing fantasies, and self-masturbation.

Low risk

There are activities that are probably safe, such as using a condom for every act of sexual intercourse, masturbating your partner or masturbating together as long as males do not ejaculate near any opening or broken skin on their partners.

Medium risk

There are activities that carry some risk, such as introducing an injured finger into the vagina. Note that having sexual intercourse with improper use of a condom also carries a risk of HIV/STI transmission.

High risk

There are activities that are very risky because they lead to exposure to the body fluids in which HIV lives. This refers to having unprotected sexual intercourse.

Dual protection is the consistent use of a male or female condom in combination with a second contraceptive method, such as oral contraceptive pills. Often young people come to a healthcare facility for contraception and are given a method that protects them only from pregnancy. As a healthcare provider, you should ensure that all young people are using a method or combination of methods that protect them from both pregnancy and STIs/HIV to minimise their risk to the lowest level possible. Box 1.1 shows important components of adolescent and youth reproductive health programmes that should be available to all young people.

Box 1.1 Services that should be provided for young people

- Information and counselling on sexual and reproductive health issues

- Promotion of healthy sexual behaviours

- Family planning information, counselling and methods of contraception (including emergency contraceptive methods)

- Condom promotion and provision

- Testing and counselling services for pregnancy, HIV and other STIs

- Management of STIs

- Antenatal care (ANC), delivery services, postnatal care (PNC) and pregnant mother-to-child transmission (PMTCT)

- Abortion and post-abortion care

- Appropriate referral linkage between health facilities at different levels.

1.4 Biological and psychosocial changes during adolescence

For young people, adolescence is all about change: in the way they think, in their bodies and in how they relate to others. As a Health Extension Practitioner it is important for you to know these changes in order to understand the special needs of young people and provide appropriate services.

1.4.1 Changes in thinking and reasoning (cognition)

Children tend to be concrete thinkers, mostly relying on literal, straightforward interpretation of ideas. In adolescence they become abstract thinkers, as they begin to be able to think abstractly and to conceptualise abstract ideas such as love, justice, fairness, truth and spirituality.

They start to analyse situations logically in terms of cause and effect, think about their futures, evaluate alternatives, set personal goals and make mature decisions.

As their abilities to think and reason increase, adolescents will become increasingly independent, and take on increased responsibilities. They will also often challenge the ideas of the adults in their community and this can lead to friction (see Figure 1.2).

1.4.2 Physical changes

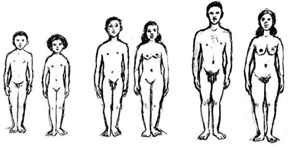

Puberty is the time in which sexual and physical characteristics mature (see Figure 1.3). The exact age a child enters puberty depends on a number of different things, such as genes, nutrition and sex. Most girls and boys enter puberty between 10-16 years of age although some start earlier or later. Girls tend to enter puberty two years before boys.

Box 1.2 details the main physical changes that occur during puberty in males and females. It is the changing hormonal activity within their bodies that brings about these changes.

Box 1.2 Physical changes during adolescence

Physical changes observed in females:

- Skin becomes oily, sometimes with pimples and acne

- Hair grows under arms, pubic area, legs

- Breasts grow

- Hips broaden, weight and height increase, hands, feet, arms, and legs become larger

- Perspiration increases and body odour may appear

- Voice deepens

- Menstruation begins, more wetness in the vaginal area.

Physical changes observed in males:

- Skin becomes oily, sometimes with pimples and acne

- Hair grows under arms, pubic areas, legs, chest, face

- Muscles especially in legs and arms get bigger and stronger

- Shoulders and chest broaden, weight and height increase, hands, feet, arms and legs become larger

- Perspiration increases and body odour may appear

- Voice cracks and then deepens

- Penis and testicles grow and begin to hang down

- Wet dreams and erection occur frequently

- Ejaculation occurs during sexual climax.

1.4.3 Social and emotional changes

As adolescents grow physically they also think and feel differently. Box 1.3 details the main social and emotional changes that take place. Some of these changes in the way they think are a consequence of growing older and learning more about the world and the way other people think and behave. But changes in the way they feel are more likely to be a consequence of the hormonal changes in their bodies. These changed feelings can often be a source of confusion and unhappiness. In this Module you will learn how you can help young people to prepare for these changes and to understand them.

Box 1.3 Social and emotional changes during puberty

- Starting to think independently/make decisions for themselves

- Starting to have sexual feelings

- Experimentation and curiosity (sexual intercourse, alcohol, drugs and other stimulants)

- Friends may matter more than they used to (what they wear, do, how they speak and use language – e.g. slang and informal speech)

- Mood changes

- Need for privacy

- Concern about body image, need to be seen as attractive and able to sexually attract people

- Need to break social sanctions and laws

- Disrespect for authority including parental supervision

- Argumentative and aggressive behaviours become evident and often disturb parents and teachers

- Delinquency/law-breaking activities

- Political extremism.

1.5 Why adolescents are especially vulnerable to reproductive health risks

Stop reading for a moment and think about this from your own experience. Why do you think adolescents exhibit more risk-taking behaviour than children or adults?

Although adolescents tend to be less informed than adults they often have a sense of having unlimited power, feelings of invulnerability and impulsiveness that can lead to reckless behaviour. They are curious and have a natural inclination to experiment. There is conflict between their own emerging values and beliefs and those of their parents and so adolescents may be trying to demonstrate these differences by experimenting with drugs and law-breaking activities.

1.6 The reproductive health situation for adolescents in Ethiopia

According to the Census conducted in 2007, Ethiopia has a population that is predominantly young (40% below the age of 15) and rural, with a high level of fertility (5.4 children per woman), early age of marriage (16 years) and a low level of contraceptive use (14%). This signifies the potential for considerable population growth for the coming years.

Young people, aged 10 to 24 years, constitute 32% of the total population, which was estimated to be around 27 million in July 2010. Ethiopia has one of the highest population growth rates in the world (2.6% per year), which has put substantial pressure on the health sector to meet the needs of the population. Projecting from the 2007 census, around 62% of the Ethiopian population were estimated to be less than 25 years of age in 2010.

Close to half the Ethiopian population (47%) lives below the poverty line, earning less than one US dollar per day. Unemployment is high, the young accounting for the majority of job-seekers.

In Ethiopia, girls have their sexual debut (first sexual experience) on average at the age of 16 years - around 5 years earlier than boys. Most girls (94%) have their sexual debut within marriage. Over a quarter of pregnant young women have unwanted pregnancies and there are therefore high abortion rates. Studies indicate that girls in late adolescence (aged 15-19 years) are twice as likely to experience obstetric fistula (explained in Study Session 5) compared with other women of reproductive age. Over half (54%) of pregnancies to girls under 15 are unwanted compared with 37% for those aged 20-24.

How would you explain the high rate of unwanted pregnancies for girls under 15?

Limited knowledge and access to reproductive health information, early marriage, limited use of contraceptives, and girls’ limited power over their sex lives all contribute to the high rate of unwanted pregnancy.

1.7 Reproductive health rights of adolescents and young people

Reproductive health rights refer to those rights specific to personal decision making and behaviour, including access to reproductive health information and services with guidance provided by trained health professionals.

The Ethiopian Government has endorsed all major international conventions concerning reproductive health rights, including those that are specific to adolescents and young people. For example, the Revised Family Law prohibits marriage of both boys and girls before the age of 18 years. Box 1.4 details all the rights for adolescents and young people which are applicable in Ethiopia.

Box 1.4 Reproductive health rights of adolescents and young people

- The right to information and education about sexual and reproductive health (SRH) services.

- The right to decide freely and responsibly on all aspects of one’s sexual behaviour.

- The right to own, control, and protect one’s own body.

- The right to be free of discrimination, coercion and violence in one’s sexual decisions and sexual life.

- The right to expect and demand equality, full consent and mutual respect in sexual relationships.

- The right to the full range of accessible and affordable SRH services regardless of sex, creed, belief, marital status or location.

These services include:

- Contraception information, counselling and services (you will study the contraceptive options for young people in Study Session 8)

- Prenatal, postnatal and delivery care

- Healthcare for infants

- Prevention and treatment of reproductive tract infections (RTIs)

- Safe abortion services as permitted by law, and management of abortion-related complications

- Prevention and treatment of infertility

- Emergency services.

Summary of Study Session 1

In Study Session 1, you have learned that:

- Adolescence is the period between 10 and 19 years of age (early adolescence is 10-14 years, late adolescence is 15-19 years and post-adolescence is 20-24 years old). Young people are those aged 10-24 years.

- Adolescents undergo significant physical, intellectual and psychosocial changes as they move into adulthood.

- In the process of moving toward independence, young people tend to experiment and test limits, including practising risky behaviour. This makes them especially vulnerable to reproductive health problems.

- Not all young people are equally affected by negative reproductive health problems. Services need to be targeted toward the most vulnerable, who include young girls in rural areas and orphans.

- Ethiopia has a population that is predominantly young and likely to grow considerably in the coming years because of the early age of marriage and low levels of contraceptive use.

- Adolescents and young people have the right to accurate information and appropriate reproductive health services. Laws protect young people’s rights.

Self-Assessment Questions (SAQs) for Study Session 1

Now that you have completed this study session, you can assess how well you have achieved its Learning Outcomes by answering these questions. Write your answers in your Study Diary and discuss them with your Tutor at the next Study Support Meeting. You can check your answers with the Notes on the Self-Assessment Questions at the end of this Module.

First read Case Study 1.1 and then answer the questions that follow it.

Case Study 1.1 Abebe’s story

Abebe is a 17-year-old boy living with his family and siblings. Recently he has become concerned by the erratic change in his voice which has embarrassed him when he is talking to people. He has also noticed that he is developing feelings of love and affection for one of the girls in his neighbourhood. His family are worried by the fact that he prefers to spend most of his time with his friends, occasionally coming back late at night without asking permission.

SAQ 1.1 (tests Learning Outcome 1.1)

How would you classify Abebe’s age group?

Answer

Abebe is 17 years old so he is in the late adolescence period.

SAQ 1.2 (tests Learning Outcome 1.3)

Read the description of Abebe again and identify one physical change associated with adolescence and one psychosocial change.

Answer

The change in his voice is a physical change. His interest in girls is a psychosocial change.

SAQ 1.3 (tests Learning Outcome 1.4)

Explain whether Abebe is at risk of engaging in risky behaviour.

Answer

Abebe is spending more time with his friends and staying out late without parental permission. It seems he might succumb to peer pressure to experiment with substances and indulge in other reckless behaviour as his behaviour is already worrying his parents.

SAQ 1.4 (tests Learning Outcomes 1.1 and 1.5)

What kinds of information and/or counselling might be most helpful to Abebe to protect his sexual and reproductive health?

Answer

Abebe should learn about the dangers of unprotected sex. He should know how STIs including HIV are acquired and how to protect himself by using a condom.

SAQ 1.5 (tests Learning Outcomes 1.1 and 1.2)

How might the concerns of a girl of Abebe’s age be different?

Answer

In general girls have their first sexual experience earlier than boys (at 16 years old) so the concerns of a girl of the same age may centre on unwanted pregnancy. However, she should also be aware of the risks of STIs and needs to be encouraged to obtain dual protection (from pregnancy and from STIs).