Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Thursday, 5 February 2026, 4:15 AM

TI-AIE: Reading for pleasure

What this unit is about

This unit focuses on your role in developing your students’ enthusiasm for reading. The more students enjoy reading, the more they will want to read. The more opportunities they have to read, the better they will become at reading. It is a virtuous circle.

As a teacher who reads and a reader who teaches, you are an important role model and can inspire your students to delight in reading.

In this unit you will be introduced to classroom practices that will help your students to develop positive attitudes towards reading, so that they have ‘the will’ to read as well as ‘the skill’ to read.

What you can learn in this unit

- How to be a reading role model for your students.

- How to plan activities that develop your students’ enjoyment of reading.

- How to organise paired reading for student peer support and collaborative learning.

Why this approach is important

Being a reader has many benefits. Reading is mentally stimulating. It develops knowledge, awareness and understanding. It enhances listening and speaking skills, and it impacts on the ability to write well. Students who don’t learn to read fluently struggle to engage in the learning opportunities available to them and run the risk of being left behind.

If we enjoy a particularly activity, we will seek out opportunities to do it more often. The more we engage in the activity, the better we get at it. This is as true for reading as for any other skill. By giving your students frequent opportunities to experience reading in an enjoyable way, you can set them on the path of becoming confident, lifelong readers.

1 Being a reading role model

Students’ attitudes to reading are strongly influenced by their teachers. This unit suggests many ways in which you can explicitly model the enjoyment to be found in reading a wide range of texts.

You will start by reading a case study of a teacher who discovered a way of introducing her students to the pleasure of reading.

Case Study 1: Reading the newspaper

Ms Rabia teaches a large group of multigrade students from Classes III–V in Sagar. Here she describes how she used newspapers to demonstrate reading for pleasure to her class.

Unfortunately, the demands of family responsibilities and work mean that I don’t have as much time to read as I would like. It is nevertheless very important to me to make my students appreciate the value and pleasure of reading.

One morning earlier this year my students came into the classroom while I was reading a story in the daily newspaper [Times of India, 2014]. When they had sat down, I put the newspaper down and said, ‘I have just been reading the most interesting thing! It is about the “Delhi Eye” – the biggest ferris wheel in India!’

I showed them a photograph of the giant wheel and continued: ‘It says here that from the top one can see monuments like Qutub Minar, Red Fort, Akshardham temple, Lotus Temple and Humayun’s Tomb.’ My students were captivated by this news.

I explained how there are many interesting things to read in the newspaper. I asked my students how often they came across newspapers outside school. One or two students said they noticed the newspapers with their photos and large-print headings in their local shop. Another said his father went to the community centre every day to read one. I learnt a little more about my students through this discussion.

From then on I shared a piece of news from the paper with my students every morning. Each time I let them observe me turning the pages, before selecting something that I thought would interest them. This was enjoyable for me, as it gave me the opportunity to read the paper every day. My students also seemed to look forward to finding out about local or international news. Through a short discussion, I was able to connect the news item with my students’ knowledge and experience, while introducing them to any new language it contained.

Soon I had a pile of newspapers and magazines in my classroom, which I encouraged my students to browse as they waited for their classmates to arrive in the morning. After a while I decided to set aside the first 15 minutes of class time for all my students to browse and read from these publications every day. Some students did this alone. Some did it together. On a few occasions I heard those reading together use the same expressions as I used with them myself, such as ‘Isn’t this interesting!’ and ‘Let’s see what this says!’ Sometimes I asked the older students to read with the younger ones. Occasionally I heard them explain what particular words meant. Recently my students have started recommending articles to one another, using expressions like ‘Have you read this?’ In these short sessions I could make informal observations of my students’ reading interests and skills.

Pause for thought

|

Ms Rabia modelled the activity of reading a newspaper to her students. She showed them how she could select from its content, sharing with them the news items that she thought they would find most interesting and inviting them to talk about their views and related experiences.

By setting aside a reading slot each day, Ms Rabia demonstrated to her students the importance of undertaking this activity on a regular basis. By providing her students with newspapers and magazines to browse, she encouraged them to choose what interested them and to share their selections with their classmates. By giving them the space to read aloud, silently or in pairs, she enabled everyone to engage with the activity at their own level. By inviting older students read to younger ones, she validated the older students’ developing skills.

One drawback to this activity is that most newspapers and magazines demand a minimum level of reading skill in order to be able to engage with them, even at a basic level. Similarly, many news items require knowledge and understanding that is beyond that expected of early grade students. The activity is therefore not appropriate for younger students or very early readers.

Whatever their level, your students will have some experience of reading. Whether positive or negative, they will also have attitudes towards reading, based on such experiences in school, at home or in their community. What kind of regular reading activity would work for your students? How can you make sure every student is included? Discuss your ideas with your colleagues.

In the next section, you will learn about the value of ‘book talk’ in the classroom. This is a regular activity that you could incorporate into any of your lessons.

2 Book talk

Pause for thought

|

Questions such as these stimulate ‘book talk’. Your answers are all important aspects of being a reader. You will see how one teacher incorporates book talk into her lesson in the case study that follows.

Case Study 2: Encouraging book talk in the classroom

Mrs Rachna is a Class VIII teacher in Bhopal. Here she explains how she went about encouraging book talk among her students.

Until last year, my usual teaching practice involved reading a text aloud to my class and asking my students to complete the associated comprehension questions in the textbook. Following a workshop at my local DIET, I decided that I needed to change my practice if I wanted my students to become more discerning about reading.

I began by choosing a story to read aloud to my class. It was ‘Children at Work’ from the NCERT Class VIII textbook And So It Happened. When I had finished reading the story, I described my response to it as follows: ‘I find this story very sad as I don’t like to read about child workers. However, it is a good adventure for the boy, Velu. I wonder what will happen to him. What do you think?’

I then asked my students to talk about the story with their partner for two minutes. I prompted them with questions such as ‘What did you like?’, ‘What didn’t you like?’ and ‘What did you find puzzling?’ Finally, I invited individual students to share their reactions to the story with the rest of the class.

At first, my students found talking about their responses to stories difficult because they were not used to expressing their opinions and reactions to texts in this way. However, after repeating this type of activity with several fiction and non-fiction reading texts, they became more comfortable about sharing their views. Now they not only feel confident in saying that they don’t enjoy a text, but they can also explain why. They have also started drawing on their background knowledge when discussing the texts, by relating them to their own experiences and indeed the other texts that they talked about and discussed previously. When my students talk freely about texts in this way, I am able to evaluate their understanding more comprehensively than through textbook exercises alone.

While I continue to use the comprehension questions in the textbook as a guide, I always allow for more open discussions about what we read in class.

Pause for thought

|

Reading comprehension does not develop automatically; it must be taught. This is best achieved through the teacher modelling the comprehension process, by thinking aloud and talking about the meaning of the texts with their students.

When students are encouraged to talk about the texts that they listen to or read themselves, they develop the confidence to speak about their reactions and interpretations.

As adults, we can usually choose what we read. We often have preferences over certain types of texts against others. We reflect on our reading and discuss it with others. We should encourage our students to do the same – to choose books that they like and respond intelligently to what they read.

Activity 1: A book talk session

Plan a short book talk session in your classroom. It should last no more than 30 minutes.

Choose a short fiction or non-fiction text. It can be a story, a factual newspaper article, a play script or a poem. Whatever text you choose, anticipate any unfamiliar vocabulary first. By introducing the topic and explaining any unknown terms at the start, you will help to reduce your students’ anxieties and support their comprehension of what follows.

After reading the text aloud, briefly tell your students what you think of it and what thoughts it provoked in you. While it is important to model book talk in this way, initially it is best to do this with care so that you don’t overly influence your students’ own responses to the same text. Follow this by inviting your students to express their reactions by asking them (for example):

- what they liked or disliked about the text

- what they thought of the characters

- whether there was anything puzzling about it

- whether they would recommend it.

Show interest in all the responses that your students offer.

If your class is large, plan a book talk session with a different group of students every day. Set the rest of the class some independent work related to the book talk reading, while you spend time with the small group. By dividing up the class according to their level, you can select texts that are appropriate to each group.

Book talk sessions should not be limited to the texts you read aloud to your students, but can extend to those they read themselves.

You may find it helpful to read the key resource ‘Talk for learning’ at this stage.

Video: Talk for learning |

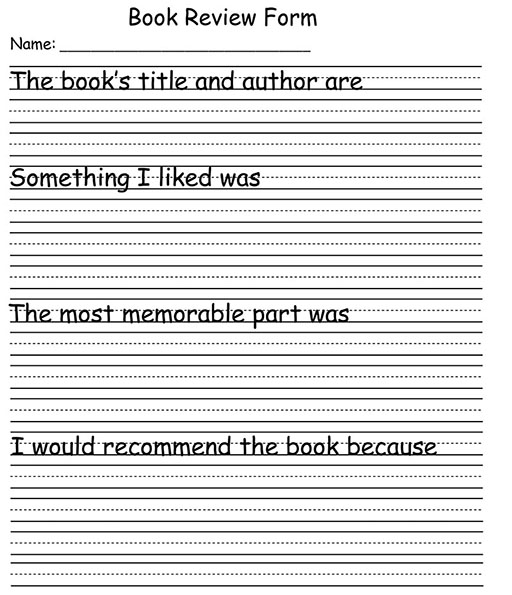

Activity 2: Student book reviews

You can extend a book talk session by getting your students to write a short review of what they have read. The book review template in Figure 2 can be adapted as you wish. As in the class discussions, all the opinions that your students express in their reviews should be accepted and valued.

In the next section, you will look at the practice of paired reading to support comprehension and enjoyment.

3 Paired reading

Reading together can be more beneficial than reading alone, and it can also be fun.

Paired reading offers a supportive, collaborative learning structure that is ideal when one student is not as confident a reader as the other. Students can be very capable and sensitive ‘teachers’ of each other. Read Resource 1, ‘Using pair work’, to learn more about organising your students in this way.

With paired reading, two students share a book and take turns to read a sentence, paragraph, or page (Figure 3). The first reader reads while the second reader listens and follows along. The second reader then continues from where the first reader stops. If one of them is struggling or makes an error, their partner can support or correct them.

You may choose to pair students of similar reading ability, or more fluent readers with less fluent readers, or older students with younger students in the case of a multi-grade classroom. If well organised, paired reading can be used with large numbers of students.

Now read the case study of a teacher who recognises the benefits of paired reading for bilingual students.

Case Study 3: Pair work for bilingual reading support

Mr Roy teaches Class V in a rural school in Madhya Pradesh.

Some of my students speak Rathwi Bareli (from the Bili group of languages) as their home language. They have made steady progress in understanding and speaking Hindi at school, but lack confidence in reading aloud. I noticed how one of my students, Surumi, used to look at books in the classroom. She seemed to be absorbed by the pictures but she did not appear understand the words on the page.

One day, I sat down beside her as she was looking at a book and asked her what the story was about. She understood my question, but found it difficult to answer. I therefore read part the book to her while pointing to the words and pictures. I asked her some simple questions and she answered in a mixture of Rathwi Bareli and Hindi.

I had the idea of asking an older student who spoke Rathwi Bareli and Hindi to read the book to Surumi. As he did so, he explained the meaning in her home language. Surumi listened attentively and responded to his questions in a mixture of Rathwi Bareli and Hindi.

I looked for other books with attractive pictures that I thought Surumi might enjoy. I found one that included well-known folk tales and a simple reader with repeating phrases. I asked a colleague to translate the stories into Rathwi Bareli so that Surumi could see them written both in Hindi and her home language. Gradually, Surumi became more familiar with Hindi and could understand more and more of these books. She is now reading slightly more difficult books with longer sentences. It has been very satisfying to observe her progress.

Pause for thought

|

We live in a diverse, multilingual society where all of our languages are valuable resources. Encouraging your students to use their home languages can help them feel confident and comfortable at school, and can help them improve their Hindi. Even if you don’t speak the same home languages as all of your students, there may be some students in the school who can help others. Students who speak the same home language can be encouraged to read in pairs or small groups. In this way they can help one another by using their home language to support the development of the school language.

The next activity is designed to help you incorporate using paired reading in your classroom.

Activity 3: Introducing and organising paired reading

This activity can be done in pairs or in small groups of three or four. Decide in advance which students you wish to pair or group together. Will they be matched by the same or differing abilities? Choose what the students are going to read, making sure you have sufficient copies of the text.

Start by modelling paired reading so that your students know what you expect them to do. Show the students the book – or the passage – that they are going to read and choose one of them to come up and be your partner. Explain that you will start by reading a paragraph aloud together and then take turns to continue reading. Start by reading the first paragraph together. Then let the student continue reading the next one. Change over and read the subsequent one yourself. Take turns several times.

Choose another student to pair up with the first one and let them demonstrate how to do paired reading together. If you plan to have larger groups, ask a third or fourth student to join in.

Tell your students that, if their partner or group member is having difficulty, they should wait a few seconds before helping them, to give them the opportunity to resolve the problem. Explain that it is better to provide the student with a clue – such as the first sound of a word – rather than the whole answer.

Initially, paired reading should last a total of ten minutes, building up to a maximum of 30 minutes as your students get used to this activity. Encourage your students to read aloud using quiet voices so as not to disturb their classmates.

Move around the class and listen carefully to check that your students have understood the activity. Give support to those who find reading difficult. Keep a note of which students have worked together, observing how well they do. While some individuals may be particularly suited to working with each other, it can also be helpful to vary pairings or groupings from time to time.

After the activity, ask your students whether they enjoyed the activity and found it useful. Praise them for helping each other. You can follow up the paired reading with a brief book talk session about the text.

4 Summary

This unit has focused on your role in enabling your students to become enthusiastic, confident and reflective readers of a range of texts within and outside the school. Your role in modelling pleasurable reading is vital to your students’ positive engagement in this activity.

This unit suggests a number of activities that you can use with increasing frequency to support reading development in the classroom. These include book talk, which provides a valuable opportunity for students to share their reactions to what they read, as well as paired reading, where students can discuss what they read together. As with many activities, reading is a skill that improves with practice, and your students are more likely to practise if they enjoy reading and talking about the texts they read.

Resources

Resource 1: Using pair work

In everyday situations people work alongside, speak and listen to others, and see what they do and how they do it. This is how people learn. As we talk to others, we discover new ideas and information. In classrooms, if everything is centred on the teacher, then most students do not get enough time to try out or demonstrate their learning or to ask questions. Some students may only give short answers and some may say nothing at all. In large classes, the situation is even worse, with only a small proportion of students saying anything at all.

Why use pair work?

Pair work is a natural way for students to talk and learn more. It gives them the chance to think and try out ideas and new language. It can provide a comfortable way for students to work through new skills and concepts, and works well in large classes.

Pair work is suitable for all ages and subjects. It is especially useful in multilingual, multi-grade classes, because pairs can be arranged to help each other. It works best when you plan specific tasks and establish routines to manage pairs to make sure that all of your students are included, learning and progressing. Once these routines are established, you will find that students quickly get used to working in pairs and enjoy learning this way.

Tasks for pair work

You can use a variety of pair work tasks depending on the intended outcome of the learning. The pair work task must be clear and appropriate so that working together helps learning more than working alone. By talking about their ideas, your students will automatically be thinking about and developing them further.

Pair work tasks could include:

- ‘Think–pair–share’: Students think about a problem or issue themselves and then work in pairs to work out possible answers before sharing their answers with other students. This could be used for spelling, working through calculations, putting things in categories or in order, giving different viewpoints, pretending to be characters from a story, and so on.

- Sharing information: Half the class are given information on one aspect of a topic; the other half are given information on a different aspect of the topic. They then work in pairs to share their information in order to solve a problem or come to a decision.

- Practising skills such as listening: One student could read a story and the other ask questions; one student could read a passage in English, while the other tries to write it down; one student could describe a picture or diagram while the other student tries to draw it based on the description.

- Following instructions: One student could read instructions for the other student to complete a task.

- Storytelling or role play: Students could work in pairs to create a story or a piece of dialogue in a language that they are learning.

Managing pairs to include all

Pair work is about involving all. Since students are different, pairs must be managed so that everyone knows what they have to do, what they are learning and what your expectations are. To establish pair work routines in your classroom, you should do the following:

- Manage the pairs that the students work in. Sometimes students will work in friendship pairs; sometimes they will not. Make sure they understand that you will decide the pairs to help them maximise their learning.

- To create more of a challenge, sometimes you could pair students of mixed ability and different languages together so that they can help each other; at other times you could pair students working at the same level.

- Keep records so that you know your students’ abilities and can pair them together accordingly.

- At the start, explain the benefits of pair work to the students, using examples from family and community contexts where people collaborate.

- Keep initial tasks brief and clear.

- Monitor the student pairs to make sure that they are working as you want.

- Give students roles or responsibilities in their pair, such as two characters from a story, or simple labels such as ‘1’ and ‘2’, or ‘As’ and ‘Bs’). Do this before they move to face each other so that they listen.

- Make sure that students can turn or move easily to sit to face each other.

During pair work, tell students how much time they have for each task and give regular time checks. Praise pairs who help each other and stay on task. Give pairs time to settle and find their own solutions – it can be tempting to get involved too quickly before students have had time to think and show what they can do. Most students enjoy the atmosphere of everyone talking and working. As you move around the class observing and listening, make notes of who is comfortable together, be alert to anyone who is not included, and note any common errors, good ideas or summary points.

At the end of the task you have a role in making connections between what the students have developed. You may select some pairs to show their work, or you may summarise this for them. Students like to feel a sense of achievement when working together. You don’t need to get every pair to report back – that would take too much time – but select students who you know from your observations will be able to make a positive contribution that will help others to learn. This might be an opportunity for students who are usually timid about contributing to build their confidence.

If you have given students a problem to solve, you could give a model answer and then ask them to discuss in pairs how to improve their answer. This will help them to think about their own learning and to learn from their mistakes.

If you are new to pair work, it is important to make notes on any changes you want to make to the task, timing or combinations of pairs. This is important because this is how you will learn and how you will improve your teaching. Organising successful pair work is linked to clear instructions and good time management, as well as succinct summarising – this all takes practice.

Additional resources

- ‘Book-talk’ by Pie Corbett: http://webfronter.com/ lewisham/ primarycommunity/ menu1/ Writing/ Talk_for_Writing/ Booktalk_by_Pie_Corbett

- Booktrust is an independent UK reading and writing charity. It provides resources and tools to support professionals in helping both children and adults to develop in their reading and writing journey: http://www.booktrust.org.uk/

- NCERT books for children: http://www.ncert.nic.in/ publication/ children_books/ children_books.html

- Pratham Books: http://www.prathambooks.org/

- ‘Children’s literature from India and the Indian diaspora’, a post on Pratham Books’ blog: http://blog.prathambooks.org/ 2010/ 10/ childrens-literature-from-india-and.html

- Dasgupta, A. (1995) Telling Tales: Children’s Literature in India. London: Taylor and Francis.

- A useful article about children’s literature in India: http://isahitya.com/ index.php/ 77-special-articles/ 269

- ‘How to teach … reading for pleasure’, from a UK website that contains some useful ideas and further links: http://www.theguardian.com/ teacher-network/ teacher-blog/ 2013/ dec/ 16/ reading-for-pleasure-reluctant-readers-schools-resources

- N’Namdi, K.A. (2005) Guide to Teaching Reading at the Primary School Level. Paris: UNESCO.

- New Approaches to Literacy Learning by V. Elaine Carter: http://unesdoc.unesco.org/ images/ 0012/ 001257/ 125767eb.pdf

References

Acknowledgements

This content is made available under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike licence (http://creativecommons.org/ licenses/ by-sa/ 3.0/), unless identified otherwise. The licence excludes the use of the TESS-India, OU and UKAID logos, which may only be used unadapted within the TESS-India project.

Every effort has been made to contact copyright owners. If any have been inadvertently overlooked the publishers will be pleased to make the necessary arrangements at the first opportunity.

Video (including video stills): thanks are extended to the teacher educators, headteachers, teachers and students across India who worked with The Open University in the productions.