Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Friday, 27 February 2026, 9:25 PM

TI-AIE: Knowing and using children’s literature

What this unit is about

India has a rich heritage of oral and written literature. With sound knowledge of children’s stories and poems, you can encourage your students to value and enjoy this legacy, and share in ownership of our nation’s languages, history and cultures.

In this unit you will:

- review your knowledge of children’s literature and take steps to extend what you know

- look at the features of children’s stories

- implement some simple classroom activities to introduce your students to literature.

What you can learn in this unit

- How to audit and extend your knowledge of literature as appropriate to your students.

- How to identify the features of high-quality children’s literature.

- Techniques for using stories and poetry in the classroom.

Why this approach is important

Stories and poems represent a tremendous resource for enriching children’s worlds beyond their immediate experience, while developing their receptive and productive language skills. Positive early experiences of listening to stories and poems will inspire children to wish to read stories and poems by themselves, thereby contributing to their literacy development. This unit encourages you to use your knowledge of traditional and modern stories and poems in the classroom to enhance your students’ language and literacy skills in enjoyable ways.

1 Auditing and extending your knowledge of children’s literature

You will start by auditing your own knowledge of children’s literature.

Activity 1: Auditing your knowledge of children’s literature

You are likely to be the main source of literature for your students. It is therefore important that you know a variety of stories and poems to read from books or recount from memory that are appropriate to your students’ age and level.

This audit not a test. Its aim is to help you to identify your starting point with regards to your knowledge of children’s literature. Try to be as honest as possible with your answers. Note down any examples that come to mind. Ask your colleagues to do an audit of their knowledge at the same time. It will be interesting to share your answers with them at the end.

Can you recite from memory:

- a poem for children?

- a rhyme that children chant?

Can you retell from memory:

- a folk tale for children?

- a short historical narrative?

Can you name:

- a character in a children’s story or folk tale?

- a character in a poem or rhyme for children?

Can you name:

- a children’s story book ?

- a children’s poetry book?

- an Indian children’s author?

- an Indian children’s poet?

Compare your audit and your thoughts with your colleagues if you can.

Pause for thought

|

You will probably have recalled some stories and poems from your childhood. You might remember a folk tale with a moral message or a warning to children to behave well, or a rhyme that you chanted in the school playground. You may have learned these stories or poems at home, in the community, and in school – maybe without ever reading them in a book. While you may be more familiar with folk stories or poems, your colleagues might recall stories by children’s authors such as R.K. Narayan, Anant Pai or Ruskin Bond. These may or may not be the same stories that children are reading today. There are also new stories that children are interested in, whether from television, comic series or local legends. These stories – old and new – can be used as a resource in your classroom, so it is useful to develop a repertoire of stories to use while teaching.

Activity 2: Extending your knowledge of children’s literature

Now make a plan to build on your audit. Set yourself a target to read:

- two children’s authors who are new to you

- two children’s poets who are new to you

Share your ideas with your colleagues.

2 Choosing literature to use in the classroom

In the case study that follows, a teacher goes to a book festival and thinks about how to incorporate what she finds there into her classroom language and literacy teaching.

Case Study 1: Mrs Aparajeeta looks for Indian children’s literature to use with her students

Mrs Aparajeeta is a Class VI teacher in Kolkata.

I wanted to bring new books into my classroom. I had to get permission to buy them from Mr Gomes, my head teacher, who agreed that I could spend a portion of the school budget on books that would be made available to the whole school.

I went to the Kolkata Book Fair to search for interesting books. I was totally overwhelmed by the huge range of reading material on sale for children, from comics through to long novels. Many were from overseas. I really had to search for Indian stories amongst all the different copies of Grimm’s Fairy Tales. I think that the bigger book publishers were targeting the parents whose children attend English medium schools. Eventually found the Saraswati Press stall full of interesting children’s literature suitable for my classes.

I began by reading the books aloud for my students’ enjoyment. Later, when they were familiar with the stories, I started to plan literacy development activities based on the texts. When a story or a poem is of a high quality, it is quite easy to plan activities around it.

Pause for thought

|

In the next activity, you will look closely at the features of high quality children’s literature.

Activity 3: Evaluating literature for children

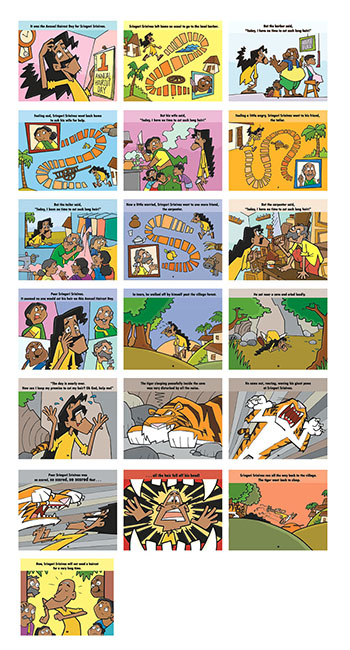

The range of literature for children is huge. You will now look at two examples: the book Annual Haircut Day (Resource 1) and the story ‘The Girl Who Married a Snake’ (Resource 2).

Read both texts aloud to yourself or a colleague. As you read, think carefully about the following questions:

- What are the differences between the two stories?

- Do you like one better than another?

- What do you think are the positive features of each text?

Look again at Annual Haircut Day and answer the following questions:

- Why does the story not begin with the words ‘Long ago …’ or ‘Once upon a time …’, as many stories do?

- Do you think the pictures are necessary? Why, or why not?

- What do you think your students would like about the story?

Compare your ideas with ours.

Annual Haircut Day is a short, lively picture book. The illustrations show people and places that are contemporary and familiar. Several of them, like the ones of the barber shop and the busy home, contain amusing details that that are appealing to look at talk about.

While the text appears simple and repetitive, it skilfully models complex language structures:

Feeling sad, Sringeri Srinivas went back home…

Feeling a little angry, Sringeri Srinivas went to his friend…

Now a little worried, Sringeri Srinivas went to one more friend…

In tears, he walked off….

Books like Annual Haircut Day are created specifically to help new readers to learn to read independently. They include carefully selected familiar words and phrases. Students can use the pictures as ‘clues’ to understanding the meaning of the text.

As students listen to or read stories like this, they will start to recognise the same words and phrases in other books and will apply this knowledge in their own speech and writing.

Stories of this kind are also useful in encouraging young children to speak and listen as they respond to questions about the pictures and what is happening in the story.

Such stories are child-friendly because they present a world that is recognisable to young readers. The satisfaction of listening to and reading these kinds of stories will inspire children’s interest in other books.

Having listened to or read stories like this, students can be invited to:

- extend the story (by adding new characters or animals, for example)

- create different endings (perhaps Sringeri Srinivas has to wear a wig after his hair falls out, because now his head is cold!)

- act it out

- tell or write their own versions of the story

- create a similar story (for example, a crocodile who has an ‘Annual Tooth-brushing Day’, using the phrase ‘Today I have no time to brush so many teeth!’ repeatedly).

Now read Resource 2, ‘The Girl Who Married a Snake’.

- How is this story different to Annual Haircut Day?

- Why do you think pictures are not necessary in this story?

- Could you retell this story to your students from memory?

- Are there places in the story where you would substitute easier words for difficult words?

- Could the story be extended or improvised, with songs, actions, dialogues or additional characters?

- Do you think your students would enjoy acting out this story?

‘The Girl Who Married a Snake’ is a traditional Panchatantra tale that starts with the phrase ‘Once upon a time …’ – the introduction to all traditional stories and a signal that it is about to begin. It is a magical story of transformation. It is not set in any particular time or place, but it does not feel like our contemporary world.

It is quite an intense, emotional story. It may feel a bit strange and disturbing.

Unlike Annual Haircut Day, the writing in this story is not simple, nor is the language that of everyday conversation.

When students listen to this story, they are exposed to complex sentences and vocabulary that they cannot yet read on their own. They learn about language through a traditional story that is a part of India’s cultural heritage.

Having listened to it, students can:

- retell the story

- invent their own versions of the story

- act out the story

- improvise dialogues between the characters

- draw or paint the scenes

- create a ‘prequel’ (What was the curse that made the son into a snake?)

- extend the story (What happens to the girl and the son? Do they have snake children?)

- perform the story for the school or the community.

Pause for thought

|

Neither story is from a school textbook. Both offer interesting situations and language to talk about. Both texts can be extended and adapted, and used for a range of language and literacy activities.

Resource 3 gives guidance on what to look for when selecting literature to use with children. Read Resource 3 now and think about the literature resources in your classroom.

3 Using poems and stories in the classroom

In the next activity, you will look at the language of a poem.

Activity 4: Appreciating poetry

Read this short poem aloud to yourself, or read it aloud with a colleague.

‘When Day Is Done’ byRabindranath Tagore

If the day is done

if birds sing no more

if the wind has flagged tired

then draw the veil of darkness thick upon me

even as thou hast wrapt the earth with the coverlet of sleep

and tenderly closed the petals of the drooping lotus at dusk.

Now answer these questions:

- Does this poem make you feel happy or sad? Why is this?

- What does it make you think about?

- Do you think very young children can appreciate it? Why,or why not?

- How would you interpret the phrases ‘a thick veil of darkness’, ‘a coverlet of sleep that wraps the earth’ and ‘drooping petals’? How would you explain them to your students?

Share your explanations of these phrases with your colleague. Could you or your student draw or physically enact these poetic images?

Pause for thought Even the youngest children can appreciate poetry when it is recited to them. They may not understand every word, but they can learn to love the sounds and rhythms of language.They will also begin to understand words and phrases that they are not yet able to read on their own.

|

Hearing high-quality literature prepares students to read these written words for themselves. The final activities in this unit guide you in introducing literature to your students.

There are many moments throughout the school day where you can read a short story or recite a poem without this impacting on the overall timetable.

To start with, do not attach any language work or writing tasks to these listening activities. Let them be enjoyable opportunities interact with your students.

Activity 5: Reciting a poem to your class

- Choose a short poem that you know well. Memorise it and practise reciting it at home or with colleagues.

- Choose a suitable time to tell it to students. This might be at the start of the school day, before or after lunch, or at the end of the day. Write the title of the poem on the blackboard.

- Make eye contact with your students when you tell it. You may need to explain some of the vocabulary, or draw it on the blackboard.

- Repeat the poem later in the week, or in the following week, so that students can get to know it.

- Invite your students to recite it along with you, perhaps adding gestures or actions.

- Invite them to recite it without you on other days, perhaps in pairs or groups. Use these occasions to observe their understanding and their language confidence.

Activity 6: Reading aloud to your class

Choose a high-quality children’s story from a book. Get to know the story well, reading it aloud at home or to colleagues.

Introduce the book to your students. Have them sit in a semi-circle around you in the classroom or outside under a tree.

Show your students the cover of the book. Ask them what they think it might be about. If the cover shows a forest, ask if anyone in the class has ever been in a forest and what this was like. If it is about rain, ask your students if they like the rain or not, and why. Read out the title and invite further guesses as to what the book might be about.

Display the book so that everyone can see the words and pictures. With younger students you may want to follow the words with your finger as you read them.

Read the story slowly and with expression, drawing attention to the pictures when they occur.

When you have finished, ask your students these questions:

- What did you like about this story?

- Was there anything you didn’t like?

- Was there anything that puzzled you? What was this?

Reread the story later the same week, or in the following week, so that your students can get to know it.

Invite your students to retell the story, perhaps in pairs or groups. Observe which students can recall the story, and which students can extend or change it. Observe which students show interest and understanding, and which students appear disinterested or confused.

Let your students’ responses guide your choice of what to read to them next.

Resource 4 includes more suggestions on using storytelling in your classroom.

Pause for thought

|

If you have never recited poetry to your students or read a story to them, you may have been nervous the first time. But both you and your students will get used to these activities when you regularly include them in your teaching, and your students will come to look forward to them and enjoy them – perhaps even eventually reciting poems or reading stories themselves.

4 Summary

In this unit, you have done an audit of your knowledge of children’s literature, and considered the features of good-quality children’s stories. You have also thought about including more opportunities for reciting poetry and telling stories in your lessons. When you regularly include activities like these in your teaching, your students will come to expect and enjoy them, and this will inspire them to read stories and poems by themselves, thereby contributing to their literacy development.

Resource 2: ‘The Girl Who Married a Snake’

Once upon a time, there lived a Brahmin with his wife in a village. Both of them were sad, as they had no children. Every day, they prayed in the hope, that one day they would be blessed with a child. Ultimately, they were blessed them with a child. The Brahmin’s wife gave birth to a baby, but the child became a snake. Everyone was horrified and advised them to get rid of the snake as soon as possible.

The Brahmin’s wife remained firm and refused to listen to anyone. She loved the snake as her son and didn’t care that her infant was a snake. She brought up the snake with love and care. She fed him with the best food she could arrange for. She made a comfortable bed in a box for him to sleep in. The snake grew up and his mother loved him all the more. On one occasion, there was a wedding in the neighbourhood. The Brahmin’s wife began to think of getting her son married. But what girl would marry a snake?

One day, when the Brahmin returned home, he found his wife in tears. He asked her, ‘What happened? Why are you crying?’ She didn’t answer and kept on crying. The Brahmin asked again, ‘Tell me what hurts you so much?’ Finally, she said, ‘I know you don’t love my son. You are not taking any interest in our son. He is grown up. You don’t even think to get him a bride.’ The Brahmin was shocked to hear such words. He replied, ‘Bride, for our son? Do you think any girl would marry a snake?’

The Brahmin’s wife didn’t respond, but she kept on crying. On seeing her crying like that, the Brahmin decided to go out in search of a bride for his son. He travelled to many places, but found no girl who was ready to marry a snake. At last, he arrived in a big city where one of his friends lived. As the Brahmin had not met him for a long time, they agreed to meet.

Both of the friends were happy to see each other and spent a good time altogether. During the conversation, the friend happened to ask the Brahmin that why he was traveling around the country. The Brahmin said, ‘I am looking for a bride for my son.’ The friend told him not to go any further and promised his daughter’s hand in marriage. The Brahmin was worried and said, ‘I think it would be better if you see my son before deciding this.’

His friend refused, saying that he knew him and his family, so it was not necessary to see the boy. He sent his daughter with the Brahmin in order to get married to his son. The Brahmin’s wife was happy to know this and quickly started making preparations for the marriage. When the villagers heard about this, they went to the girl and warned her not to marry the snake. The girl refused to listen to them and insisted that she had to keep her father’s word.

Accordingly, the marriage between the snake and the girl took place. The girl started living with her husband, the snake. She was a devoted wife and looked after the snake like a good wife. The snake slept in his box at night. One night, when the girl was going to sleep, she saw a handsome young man in the room. She was frightened and was about to run for help. The young man stopped her and said, ‘Don’t fear. Didn’t you recognise me? I am your husband.’

The girl didn’t believe him. The young man proved himself by entering into the snake’s skin and then came out of it once again as the young man. The girl was so happy to find her husband in a human form and fell at his feet. From that night onwards, every night the young man would come out of the snake’s skin. He used to stay with his wife till daybreak and then would slip back into the snake’s skin.

One night, the Brahmin heard voices from his daughter-in-law’s room. He kept a watch and saw the snake turning into a young man. He rushed into the room, seized the snake’s skin and threw it into the fire. The young man said, ‘Dear Father, thank you very much. Due to a curse, I had to remain a snake until somebody, without asking me, destroyed the snake’s body. Today, you have done it. Now, I am now free from the curse.’ Thus, the young man never became a snake again and lived happily with his wife.

Resource 3: Choosing children’s literature for the classroom

It is important to expose students to a wide range of engaging stories and poems on a variety of themes.

- Books and poems for young children can help them to:

- learn to recognise letters, familiar words and phrases

- learn to use pictures to predict and interpret words

- learn word and sentence patterns that they can apply to other reading

- gain confidence as readers.

In selecting suitable texts for younger children, you should look out for:

- familiar situations, such as home or community activities

- patterns and sequences, such as numbers, days of the week, the weather or daily routines

- repeated words and phrases, with variations

- a strong correspondence between words and pictures

- interesting images (photographs, pictures or drawings) for students to talk about

- shortness in length to maintain students’ attention and encourage them to read the text themselves.

- Books and poems for older children can help them to:

- learn to use high-level vocabulary and phrases

- understand the power of stories and reading

- learn about their history and traditions

- develop an understanding of dilemmas and problems.

In selecting suitable texts for older children, you should look out for:

- exciting narratives and interesting characters

- drama, conflict and resolutions, journeys, or transformations

- humour or interesting dialogue

- opportunities for children to reflect

- important messages.

Resource 4: Storytelling, songs, role play and drama

Students learn best when they are actively engaged in the learning experience. Your students can deepen their understanding of a topic by interacting with others and sharing their ideas. Storytelling, songs, role play and drama are some of the methods that can be used across a range of curriculum areas, including maths and science.

Storytelling

Stories help us make sense of our lives. Many traditional stories have been passed down from generation to generation. They were told to us when we were young and explain some of the rules and values of the society that we were born into.

Stories are a very powerful medium in the classroom: they can:

- be entertaining, exciting and stimulating

- take us from everyday life into fantasy worlds

- be challenging

- stimulate thinking about new ideas

- help explore feelings

- help to think through problems in a context that is detached from reality and therefore less threatening.

When you tell stories, be sure to make eye contact with students. They will enjoy it if you use different voices for different characters and vary the volume and tone of your voice by whispering or shouting at appropriate times, for example. Practise the key events of the story so that you can tell it orally, without a book, in your own words. You can bring in props such as objects or clothes to bring the story to life in the classroom. When you introduce a story, be sure to explain its purpose and alert students to what they might learn. You may need to introduce key vocabulary or alert them to the concepts that underpin the story. You may also consider bringing a traditional storyteller into school, but remember to ensure that what is to be learnt is clear to both the storyteller and the students.

Storytelling can prompt a number of student activities beyond listening. Students can be asked to note down all the colours mentioned in the story, draw pictures, recall key events, generate dialogue or change the ending. They can be divided into groups and given pictures or props to retell the story from another perspective. By analysing a story, students can be asked to identify fact from fiction, debate scientific explanations for phenomena or solve mathematical problems.

Asking the students to devise their own stories is a very powerful tool. If you give them structure, content and language to work within, the students can tell their own stories, even about quite difficult ideas in maths and science. In effect they are playing with ideas, exploring meaning and making the abstract understandable through the metaphor of their stories.

Songs

The use of songs and music in the classroom may allow different students to contribute, succeed and excel. Singing together has a bonding effect and can help to make all students feel included because individual performance is not in focus. The rhyme and rhythm in songs makes them easy to remember and helps language and speech development.

You may not be a confident singer yourself, but you are sure to have good singers in the class that you can call on to help you. You can use movement and gestures to enliven the song and help to convey meaning. You can use songs you know and change the words to fit your purpose. Songs are also a useful way to memorise and retain information – even formulas and lists can be put into a song or poem format. Your students might be quite inventive at generating songs or chants for revision purposes.

Role play

Role play is when students have a role to play and, during a small scenario, they speak and act in that role, adopting the behaviours and motives of the character they are playing. No script is provided but it is important that students are given enough information by the teacher to be able to assume the role. The students enacting the roles should also be encouraged to express their thoughts and feelings spontaneously.

Role play has a number of advantages, because it:

- explores real-life situations to develop understandings of other people’s feelings

- promotes development of decision making skills

- actively engages students in learning and enables all students to make a contribution

- promotes a higher level of thinking.

Role play can help younger students develop confidence to speak in different social situations, for example, pretending to shop in a store, provide tourists with directions to a local monument or purchase a ticket. You can set up simple scenes with a few props and signs, such as ‘Café’, ‘Doctor’s Surgery’ or ‘Garage’. Ask your students, ‘Who works here?’, ‘What do they say?’ and ‘What do we ask them?’, and encourage them to interact in role these areas, observing their language use.

Role play can develop older students’ life skills. For example, in class, you may be exploring how to resolve conflict. Rather than use an actual incident from your school or your community, you can describe a similar but detached scenario that exposes the same issues. Assign students to roles or ask them to choose one for themselves. You may give them planning time or just ask them to role play immediately. The role play can be performed to the class, or students could work in small groups so that no group is being watched. Note that the purpose of this activity is the experience of role playing and what it exposes; you are not looking for polished performances or Bollywood actor awards.

It is also possible to use role play in science and maths. Students can model the behaviours of atoms, taking on characteristics of particles in their interactions with each other or changing their behaviours to show the impact of heat or light. In maths, students can role play angles and shapes to discover their qualities and combinations.

Drama

Using drama in the classroom is a good strategy to motivate most students. Drama develops skills and confidence, and can also be used to assess what your students understand about a topic. A drama about students’ understanding of how the brain works could use pretend telephones to show how messages go from the brain to the ears, eyes, nose, hands and mouth, and back again. Or a short, fun drama on the terrible consequences of forgetting how to subtract numbers could fix the correct methods in young students’ minds.

Drama often builds towards a performance to the rest of the class, the school or to the parents and the local community. This goal will give students something to work towards and motivate them. The whole class should be involved in the creative process of producing a drama. It is important that differences in confidence levels are considered. Not everyone has to be an actor; students can contribute in other ways (organising, costumes, props, stage hands) that may relate more closely to their talents and personality.

It is important to consider why you are using drama to help your students learn. Is it to develop language (e.g. asking and answering questions), subject knowledge (e.g. environmental impact of mining), or to build specific skills (e.g. team work)? Be careful not to let the learning purpose of drama be lost in the goal of the performance.

Additional resources

- There are a number of fiction and non-fiction books for children in the NCERT catalogue, in both Hindi and English, which may be used in activities similar to those described in this unit: http://www.ncert.nic.in/ publication/ children_books/ children_books.html

- A list of children’s literature recommended by the Department of Elementary Education in both Hindi and English can be found here on their website: http://www.ncert.nic.in/ departments/ nie/ dee/ publication/ Print_Material.html

- Other organisations producing literature for children include Room to Read India (http://www.roomtoread.org/ Page.aspx?pid=304) and Pratham Books (http://www.prathamusa.org/ programs/ library, http://blog.prathambooks.org/ 2010/ 10/ childrens-literature-from-india-and.html)

- Traditional Indian stories: http://www.indiaparenting.com/ stories/ index.shtml#77

- Indian fables: http://excellup.com/ kidsImage/ panchtantra/ panchatantra_list.aspx

References

Acknowledgements

Except for third party materials and otherwise stated below, this content is made available under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike licence (http://creativecommons.org/ licenses/ by-sa/ 3.0/). The material acknowledged below is Proprietary and used under licence for this project, and not subject to the Creative Commons Licence. This means that this material may only be used unadapted within the TESS-India project and not in any subsequent OER versions. This includes the use of the TESS-India, OU and UKAID logos.

Grateful acknowledgement is made to the following sources for permission to reproduce the material in this unit:

Resource 1: Annual Haircut Day, written by Noni, illustrations by Angie and Upesh, © Pratham Books. Made available under http://creativecommons.org/ licenses/ by-nc-sa/ 2.5/ in/.

Every effort has been made to contact copyright owners. If any have been inadvertently overlooked the publishers will be pleased to make the necessary arrangements at the first opportunity.

Video (including video stills): thanks are extended to the teacher educators, headteachers, teachers and students across India who worked with The Open University in the productions.