Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Friday, 27 February 2026, 9:24 PM

TI-AIE: Language, literacy and citizenship

What this unit is about

This unit is a guide to planning a thematic class project on citizenship. It describes how to devise and monitor a series of interconnected activities that encourage your students to be inclusive, reflective and considerate as they participate in a range of meaningful, communicative tasks within and outside the school.

What you can learn in this unit

- How to plan and organise a thematic project that develops your students’ citizenship skills.

- How to identify opportunities for incorporating a wide variety of language- and literacy-based activities within the project.

- How to monitor your students’ learning in relation to both citizenship and language and literacy.

Why this approach is important

A thematic project offers your students the scope to explore topics that:

- interest and motivate them

- combine different subject areas

- engage them in purposeful collaborative activities which combine listening, speaking, reading and writing skills.

Projects are a way of enhancing the curriculum and textbook imaginatively and memorably. Citizenship-focused projects have the added advantage of raising students’ awareness of values and responsibilities in society while developing their respect for other beliefs and ideas. As such, they reflect broader educational objectives, relating to human rights and duties, justice, liberty, and equality. In this way, they relate school learning to students’ immediate lives.

1 Thinking about language, literacy and citizenship

Activity 1: Thinking about language, literacy and citizenship

With a colleague, read Resource 1. You may already be familiar with this document. When you have read it through once, read it again, making notes of your answers to the following questions:

- What kinds of behaviours would a good citizen demonstrate?

- In what ways can schools help students to learn to be good citizens?

- What kinds of language or literacy skills could help students to become good citizens?

Discuss your ideas with your colleague.

Now compare your ideas with ours.

Good citizens:

- use their knowledge and skills to contribute to a better community and world

- are prepared to voice their concerns and propose solutions

- are thoughtful, inclusive and considerate

- act in accordance with what they believe.

Schools play a vital role in helping students to become good citizens by providing opportunities for them to:

- learn how to understand and analyse difficult issues

- propose solutions that are fair and ethical

- listen to others

- respectfully voice their beliefs and concerns

- interact positively with a diverse group of individuals.

Language and literacy skills can help students to become good citizens by enabling them to:

- read, understand, analyse and interpret information – whether in the form of images, speech or writing

- separate facts from opinions

- collect and evaluate evidence

- explain, summarise and predict

- discuss topics, listening to the views of others and expressing their own viewpoints

- ask questions that elicit sound responses

- persuade others in an appropriate manner

- make posters, write letters and design petitions

- present information to different audiences through images, speech and writing.

Although many citizenship-related topics relate to serious issues, is it still possible to explore them in enjoyable, engaging ways.

You will now read about a teacher who undertook a project on the village community with her class. As you read the case study, think about the language and literacy skills that her students were developing and the aspects of citizenship they were learning about.

Case Study 1: Our village community

Ms Rakshi teaches in a village school in Uttar Pradesh. Here she describes the first of a series of lessons that formed part of a classroom project on the concept of ‘Community’, which she undertook with her Class VI students.

Lesson 1: Thinking about our village community

I introduced the project by asking my students to think about the places and people that made up the village community. To help them, I provided one or two examples of each, such as the temple and the school, along with Mr Rajeshree, the sarapanch, and Mrs Sutapa, the seamstress.

I then organised my students into groups of four to share their ideas. After 15 minutes, I went around the class, inviting a suggestion from each student. As I wrote their contributions on the blackboard, we discussed whether it was better to list the places and people in separate columns or associate the two together.

I then asked the groups to make a community map on the ground in the school yard using stones, sticks, leaves, seeds or anything else they wished to represent its features.

When they had finished, each group presented their map to the rest of the class, describing the locations they had included – such as religious centres, the bazaar, shops, fields, houses and water sources – and referring to some of the people associated with them. This was very interesting, and the maps and descriptions were so varied. I took a photograph of each map with my mobile phone as a record of part of the project.

Lesson 2: Living together in a community

The following week I explained that we would be considering the meaning of living in a community. To encourage my students to work with and learn from a range of classmates, I divided them into different groups from those they had worked in before.

I gave each group a large piece of paper on which I had written a single question. Here are the questions I gave them:

- What kinds of things do the children do together in our community?

- What kinds of things do the women do together in our community?

- What kinds of things do the men do together in our community?

- What kinds of things are men, women and children involved in together?

- How do people in our community help someone who becomes sick?

- What do people do in our community when a person dies?

I asked the members of each group to discuss their allocated question for 20 minutes, illustrating their ideas with a picture accompanied by notes.

When the groups had finished, I posted their pictures on the wall. I then asked them to nominate someone from their group to share their ideas with the rest of the class. This generated a very interesting discussion, in which we explored the notion of sub-communities within a larger community, and the nature of the tasks that such sub-communities tend to undertake.

Lesson 3: The advantages and disadvantages of community life

I asked my students to copy out the following questions and make notes of their answers for their homework.

- What are the advantages of living in a community?

- What might be the disadvantages?

- How can people who feel isolated in a community be helped to become more integrated?

The next day, I placed my students in pairs and asked them to discuss their homework with each other. This was followed by a whole-class discussion in which I tried to ensure that those who had not contributed before had a chance to speak.

Lesson 4: Community government

We began this lesson by listing of all the people in the village who had responsible positions and considering what their responsibilities were. My students named many different people with different roles, including teachers such as me.

Rather than write up their ideas on the blackboard myself, I invited two volunteers to do so in turn. They were very proud of taking on this task and used their best handwriting in the process. If they made spelling errors, their classmates suggested corrections.

I then divided the class into pairs and gave them 15 minutes to consider two further questions:

- Who is responsible for seeing that people cooperate in our community?

- What happens when people disagree about something? Who helps them settle their disputes?

In the whole-class discussion that followed, we talked about the concept of local government as a system that oversees the interests of the community and examined the way in which this worked in our village, along with the processes whereby members of the community took on responsibilities of this kind.

Finally, I encouraged my students to think about what they could do to contribute more actively to the community. I gave them each a strip of paper on which they each wrote a sentence, which they could illustrate if they wished. I then I displayed the sentences on the wall for everyone to see

I had initially been a little nervous as to whether my students would engage with a project on their local community. I need not have worried, however. The topic generated many interesting, thoughtful contributions, some from students who were normally very quiet. I was pleased too at the level of collaboration and respect that was evident in the different pairings and groupings over the four lessons.

Pause for thought For each of the lessons described above, consider the following questions:

|

2 Planning a citizenship project

As Case Study 1 shows, a thematic project is intended to span a number of lessons over a period of several weeks. The remaining activities in this unit are intended to be a practical guide to planning a citizenship project that incorporates language- and literacy-related objectives for your class. The activity is divided into six parts (Activities 2–7). Read the whole activity through carefully first and then work though it part by part as you progress through your chosen topic.

Activity 2: Identifying a topic for the project

With a colleague, make a list of possible citizenship-related topics for your class. Your list is likely to be tailored to your school and community context; however, we have suggested some topics below:

- ways of making the school more attractive

- keeping the village clean

- obtaining blankets for new born babies or for elderly people in the village

- helping lonely, disabled, and sick people in the community

- organising a sale of items to raise money for a local cause

- collecting children’s books for the anganwadis ,schools or homes in the area

- recycling paper, food or household items that are no longer used

- addressing local problems of dumping waste

- saving energy

- conserving water

- preventing water-borne diseases

- improving healthcare for girls and women, including recruiting more female healthcare workers

- female – rather than male – students having to do household chores and not being able to play freely outside

- the problem of animals being hunted to extinction

- the impact of current and future climate changes upon the environment

- promoting the use of local minority languages.

Which topics in your list would be most suitable for you and your class?

Some of the factors that you may have taken into account in making your decision are:

- whether the topics are age-appropriate, relevant and interesting to all your students

- how far they align with the content of your school curriculum

- what subjects – such as maths, environmental studies, science, or social studies – they embrace

- whether the topics are overly sensitive or controversial

- how confident and comfortable you are in investigating them with your class.

Now list the language- and literacy-related opportunities that your selected topics lend themselves to. Here are some suggestions to get you started:

- reading newspapers or other texts to understand the issue and its causes

- interviewing a local person

- organising a debate

- writing a class letter to a politician or newspaper editor

- creating and distributing leaflets or posters

- organising an awareness-raising campaign, starting a petition or devising a fundraising initiative

- writing a play on the issue to present to the other students in the school or to members of the local community.

3 Engaging your students in a citizenship project

Whether you invite your students to suggest a topic themselves, offer them selection to choose from, or propose a topic of your choice, part of the process of engaging your students in a class project involves listening to and responding to their suggestions and ideas.

Whichever approach you take regarding the choice of topic, it is helpful to begin by discussing the concept of citizenship with your students.

Activity 3: Engaging your students in a class project

Explain to your students that they are going to do a class project and that you would like their suggestions as to what it might involve. Organise the class into groups. Provide each group with a piece of paper headed with a question or choice of topics to prompt their discussions – for example:

- In what ways can we make our school more attractive?

- How can we improve our village?

Ask every student to contribute at least one idea to the discussion and write it on the piece of paper. When the time is up, invite volunteers from each group to feed back to the whole class. Write the ideas on the blackboard, ensuring that that everyone listens respectfully to their classmates’ suggestions.

Once the list is complete, ask your students to talk in their groups about the ideas they liked best. If appropriate, bring the class back together for a vote.

Through discussions such as these, your students will develop citizenship skills by thinking about issues that concern them, by voting, and by reaching agreement. They will develop language and literacy skills by listening, discussing, note-taking and feeding back to the rest of the class. These two strands of learning should be followed through throughout the project.

Pause for thought What did you learn about your students from doing this activity with them? |

For more ideas about involving all your students in classroom learning, see Resource 2.

Identifying sources of information for the project

The next step in the project is to invite your students to suggest ways of finding out about the topic.

Activity 4: Researching the topic

Note down all the sources of information that they propose on the blackboard. These might include school textbooks, a library, a newspaper, the Internet, a health centre, posters, leaflets, a local government office or local people.

If, for example, your students choose to learn about water-borne diseases, they could visit the local water purification site and, by prior arrangement and with permission, interview one of the water regulators. Alternatively they could visit the community Primary Health Centre or hospital for advice on water purification and safety. They might also consult an information leaflet to learn what families can do to protect themselves from water-borne diseases.

Whether it involves reading newspapers, books, posters or information leaflets, speaking to local experts, visiting relevant places, and taking notes on what is read, seen and heard, all such research will involve a variety of language and literacy skills.

4 Outlining the citizenship project

Activity 5: Outlining and scheduling the project

Make a detailed plan of the project. A table format with several columns works best for this.

- Begin by listing all the activities that you anticipate the project will involve.

- Note alongside each activity the language and learning opportunities that it offers.

- Decide which of the activities will be undertaken by the whole class and which are more suited to being distributed across small groups.

- Note down what you will need to organise in advance of each activity. This might include collecting particular resources, contacting local experts or gaining permissions for class visits. In each case, consider how much preparation time you require.

- Now plan a series of lessons that cover the different activities that you have identified over the next few weeks, sequencing them in an appropriate order.

- When you have finished, schedule each lesson into your teaching timetable, bearing in mind its fit with other subject areas in the curriculum. You may wish to allow a little extra time in the schedule to accommodate any unforeseen circumstances.

- Share this planning process with a colleague if helpful.

You may find the key resource ‘Planning lessons’ helpful.

Video: Planning lessons |

5 Ways of presenting your students’ learning

Activity 6: Presenting your students’ learning

There are many ways that students can present and share their learning over the course of the project. Whether undertaken individually or collaboratively, this might take the form of a written report, a poster, artwork, a performance , songs, stories and poems, or community action.

Your students might like to present their learning to the headteacher and school staff, parents, village elders, the panchayat raj or sarapanch, or even national government representatives. You could encourage your students to write a letter or report for a newspaper so that a wider audience can read about their learning. Where possible, take photos of your students engaging in this project to display and share with others.

Activity 7: Reflecting on your students’ learning

What do you think your students learnt about citizenship by undertaking the thematic project? Did you observe them gaining knowledge and understanding of any of the following?

- democracy, justice and equality

- current topics that are important to themselves or their community

- being aware of themselves as members of the global community

- treating others with dignity and respect

- being proactive

- mentoring one another

- defending one another.

What other citizenship-related knowledge and understanding did you observe over this period, and how can you capture this information in a progress and development chart for all your students?

What did your students learn about language and literacy through the thematic project? Did you observe them using any of these skills?

- reading for information

- writing about what they read, hear or see

- interview techniques

- evaluating information

- expressing opinions

- debating respectfully

- giving a presentation

- non-verbal communication.

How were you able to involve all your students in the thematic project according to their interests and abilities?

In what ways did you show that you valued all their contributions, and did any students contribute in ways you hadn’t expected?

6 Summary

This unit has outlined a plan to enable you to devise and implement a thematic class project that integrates the development of the values associated with good citizenship on the one hand, and language and literacy objectives on the other, with the acquisition of subject knowledge through a series of lessons spanning several weeks. By engaging in imaginative, collaborative, community-orientated activities involving research, discussion, observation and dissemination, students gain intellectually and socially while retaining positive memories of such learning experiences. Projects such as these can be adapted to suit students of any level, and once you have planned them you can use and develop your planning year after year. If you have the opportunity to share the planning and implementation of a project with another colleague, you will find the process particularly rewarding.

Resources

Resource 1: The fundamental duties of citizens in India

It shall be the duty of every citizen of India:

- a.To abide by the Constitution and respect its ideals and institutions, the National Flag and the National Anthem.

- b.To cherish and follow the noble ideals which inspired our national struggle for freedom;

- c.To uphold and protect the Sovereignty, unity and integrity of India;

- d.To defend the country and render national service when called upon to do so;

- e.To promote harmony and the spirit of common brotherhood amongst all the people of India transcending religious, linguistic and regional or sectional diversities; to renounce practices derogatory to the dignity of women;

- f.To value and preserve the rich heritage of our composite culture;

- g.To protect and improve the natural environment including forests, lakes, rivers and wild life, and to have compassion for living creatures;

- h.To develop the scientific temper, humanism and the spirit of inquiry and reform.

- i.To safeguard public property and to abjure violence;

- j.To strive towards excellence in all spheres of individual and collective activity, so that the nation constantly rises to higher levels of endeavour and achievement

Resource 2: Involving all

What does it mean to ‘involve all’?

The diversity in culture and in society is reflected in the classroom. Students have different languages, interests and abilities. Students come from different social and economic backgrounds. We cannot ignore these differences; indeed, we should celebrate them, as they can become a vehicle for learning more about each other and the world beyond our own experience. All students have the right to an education and the opportunity to learn regardless of their status, ability and background, and this is recognised in Indian law and the international rights of the child. In his first speech to the nation in 2014, Prime Minister Modi emphasised the importance of valuing all citizens in India regardless of their caste, gender or income. Schools and teachers have a very important role in this respect.

We all have prejudices and views about others that we may not have recognised or addressed. As a teacher, you carry the power to influence every student’s experience of education in a positive or negative way. Whether knowingly or not, your underlying prejudices and views will affect how equally your students learn. You can take steps to guard against unequal treatment of your students.

Three key principles to ensure you involve all in learning

- Noticing:Effective teachers are observant, perceptive and sensitive; they notice changes in their students. If you are observant, you will notice when a student does something well, when they need help and how they relate to others. You may also perceive changes in your students, which might reflect changes in their home circumstances or other issues. Involving all requires that you notice your students on a daily basis, paying particular attention to students who may feel marginalised or unable to participate.

- Focus on self-esteem:Good citizens are ones who are comfortable with who they are. They have self-esteem, know their own strengths and weaknesses, and have the ability to form positive relationships with other people, regardless of background. They respect themselves and they respect others. As a teacher, you can have a significant impact on a young person’s self-esteem; be aware of that power and use it to build the self-esteem of every student.

- Flexibility: If something is not working in your classroom for specific students, groups or individuals, be prepared to change your plans or stop an activity. Being flexible will enable you make adjustments so that you involve all students more effectively.

Approaches you can use all the time

- Modelling good behaviour:Be an example to your students by treating them all well, regardless of ethnic group, religion or gender. Treat all students with respect and make it clear through your teaching that you value all students equally. Talk to them all respectfully, take account of their opinions when appropriate and encourage them to take responsibility for the classroom by taking on tasks that will benefit everyone.

- High expectations:Ability is not fixed; all students can learn and progress if supported appropriately. If a student is finding it difficult to understand the work you are doing in class, then do not assume that they cannot ever understand. Your role as the teacher is to work out how best to help each student learn. If you have high expectations of everyone in your class, your students are more likely to assume that they will learn if they persevere. High expectations should also apply to behaviour. Make sure the expectations are clear and that students treat each other with respect.

- Build variety into your teaching:Students learn in different ways. Some students like to write; others prefer to draw mind maps or pictures to represent their ideas. Some students are good listeners; some learn best when they get the opportunity to talk about their ideas. You cannot suit all the students all the time, but you can build variety into your teaching and offer students a choice about some of the learning activities that they undertake.

- Relate the learning to everyday life:For some students, what you are asking them to learn appears to be irrelevant to their everyday lives. You can address this by making sure that whenever possible, you relate the learning to a context that is relevant to them and that you draw on examples from their own experience.

- Use of language:Think carefully about the language you use. Use positive language and praise, and do not ridicule students. Always comment on their behaviour and not on them. ‘You are annoying me today’ is very personal and can be better expressed as ‘I am finding your behaviour annoying today. Is there any reason you are finding it difficult to concentrate?’,which is much more helpful.

- Challenge stereotypes:Find and use resources that show girls in non-stereotypical roles or invite female role models to visit the school, such as scientists. Try to be aware of your own gender stereotyping; you may know that girls play sports and that boys are caring, but often we express this differently, mainly because that is the way we are used to talking in society.

- Create a safe, welcoming learning environment:All students need to feel safe and welcome at school. You are in a position to make your students feel welcome by encouraging mutually respectful and friendly behaviour from everyone. Think about how the school and classroom might appear and feel like to different students. Think about where they should be asked to sit and make sure that any students with visual or hearing impairments, or physical disabilities, sit where they can access the lesson. Check that those who are shy or easily distracted are where you can easily include them.

Specific teaching approaches

There are several specific approaches that will help you to involve all students. These are described in more detail in other key resources, but a brief introduction is given here:

- Questioning:If you invite students to put their hands up, the same people tend to answer. There are other ways to involve more students in thinking about the answers and responding to questions. You can direct questions to specific people. Tell the class you will decide who answers, then ask people at the back and sides of the room, rather than those sitting at the front. Give students ‘thinking time’ and invite contributions from specific people. Use pair or groupwork to build confidence so that you can involve everyone in whole-class discussions.

- Assessment:Develop a range of techniques for formative assessment that will help you to know each student well. You need to be creative to uncover hidden talents and shortfalls. Formative assessment will give you accurate information rather than assumptions that can easily be drawn from generalised views about certain students and their abilities. You will then be in a good position to respond to their individual needs.

- Groupwork and pair work:Think carefully about how to divide your class into groups or how to make up pairs, taking account of the goal to include all and encourage students to value each other. Ensure that all students have the opportunity to learn from each other and build their confidence in what they know. Some students will have the confidence to express their ideas and ask questions in a small group, but not in front of the whole class.

- Differentiation:Setting different tasks for different groups will help students start from where they are and move forward. Setting open-ended tasks will give all students the opportunity to succeed. Offering students a choice of task helps them to feel ownership of their work and to take responsibility for their own learning. Taking account of individual learning needs is difficult, especially in a large class, but by using a variety of tasks and activities it can be done.

Additional resources

- ‘Learning about rights in Year 2’: http://globaldimension.org.uk/ pages/ 8668

- National Policy on Education (1986 and 1992): http://www.childlineindia.org.in/ pdf/ National-Policy-on-Education.pdf

- National Curriculum for Elementary and Secondary Education (1988): http://www.teindia.nic.in/ mhrd/ 50yrsedu/ q/ 91/ HL/ toc.htm

- UNESCO language studies: http://www.unesco.org/ education/ tlsf/ mods/ theme_b/ popups/ mod06t04s04.html

- Right Here, Right Now: Teaching Citizenship through Human Rights, published by the UK Ministry of Justice, the British Institute of Human Rights, the UK Department for Children, Schools and Families, and Amnesty International UK: http://www.amnesty.org.uk/ sites/ default/ files/ book_-_right_here_right_now_0.pdf

- ‘Language across curriculum’ by Nisha Butoliya: http://www.teachersofindia.org/ en/ lesson-plan/ language-across-curriculum

- UNICEF India: http://www.unicef.org/ india/ wes.html

- ‘What is academic language?’ by James Paul Gee, which includes furtherdiscussion of the issues raised in the introduction: http://www.jamespaulgee.com/ sites/ default/ files/ pub/ TeachingSciencetoELL-Ch07.pdf

- Democratic Citizenship, Languages, Diversity and Human Rights by Hugh Starkey: https://www.coe.int/ t/ dg4/ linguistic/ Source/ StarkeyEN.pdf

References

Acknowledgements

Except for third party materials and otherwise stated below, this content is made available under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike licence (http://creativecommons.org/ licenses/ by-sa/ 3.0/). The material acknowledged below is Proprietary and used under licence for this project, and not subject to the Creative Commons Licence. This means that this material may only be used unadapted within the TESS-India project and not in any subsequent OER versions. This includes the use of the TESS-India, OU and UKAID logos.

Grateful acknowledgement is made to the following sources for permission to reproduce the material in this unit:

Figure 1: http://ww.ifrc.org.

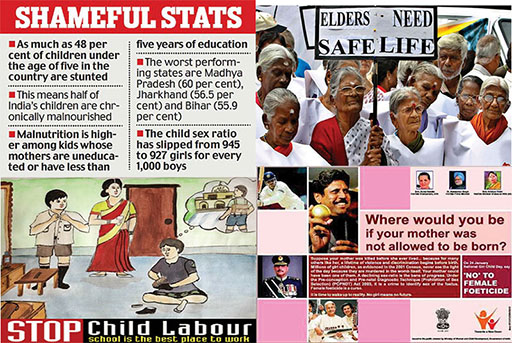

Figure 3: top left, adapted from ‘Child growth stats show half of india’s children are chronically malnourished’, Pratul Sharma, 7 October 2012, Mail Online India, http://www.dailymail.co.uk; top right, http://www.saferinindia.org; bottom left, http://happy-2013.blogspot.com/ 2014/ 05/; bottom right, http://www.pakool.com.

Figure 4: top left, http://www.childlineindia.org.in; top middle, http://newswatch.nationalgeographic.com; right, http://ncert.nic.in; bottom left, http://www.kidsfortigers.org; bottom middle, AFP=JIJI http://www.jijiphoto.jp.

Resource 1: http://home.bih.nic.in.

Every effort has been made to contact copyright owners. If any have been inadvertently overlooked the publishers will be pleased to make the necessary arrangements at the first opportunity.

Video (including video stills): thanks are extended to the teacher educators, headteachers, teachers and students across India who worked with The Open University in the productions.