Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Wednesday, 4 February 2026, 9:51 AM

TI-AIE: Pair work for language and literacy

What this unit is about

This unit focuses on ways of planning and managing pair work in your language lessons. By providing opportunities for sociable, collaborative learning in many different activity types, pair work can be a very effective tool in your teaching repertoire.

What you can learn in this unit

- How to plan for and manage pair work in your language lessons.

- How to extend your repertoire of classroom management techniques.

- How to use pair work as an opportunity to assess your students’ language and literacy development.

Why this approach is important

In everyday situations, people work alongside one another, speaking and listening, watching, supporting, suggesting, and assisting. Such forms of collaboration encourage the exchange of ideas and open the door to different ways of doing things. If everything is centred on the teacher in the classroom, there will be very few opportunities for students to explore, discuss, question, experiment and learn in natural, mutually beneficial ways. Using pair work is a very effective way of incorporating talk-based learning opportunities of this kind into your language lessons.

Pair work is suitable for all ages and all subjects. Because it enables many students to talk at the same time, it is particularly effective with large classes. It is highly inclusive in that it requires all students to communicate. It is especially useful in multilingual, multi-grade classes, as pairings can be organised flexibly and supportively in line with your students’ needs. Whether you combine students according to similar attainment levels, different attainment levels, the same home language friendships, or allocate them randomly, varying your approach to pairing can have the effect of stimulating learning while enhancing classroom relationships.

1 Why should you use pair work?

Activity 1 encourages you to reflect on using pair work in your language lessons.

Activity 1: Reflecting on using pair work in the classroom

With a colleague, if possible, start by reading Resource 1, ‘Using pair work’. Underline what you consider to be the key learning points of the text for you as a teacher.

Think of one or two lessons that you have taught recently. These might focus on language or on a specific subject area.

- Were there opportunities for pair work? If so, what were they?

- Did you use these them to get your students to work in pairs? If so, how successful were they?

- If you are new to pair work, what concerns do you have about implementing it as a regular practice in your classroom?

2 Examples of lessons with pair work

In this first case study you will read about a teacher who employed pair work in a poetry writing activity.

Case Study 1: Using pair work in a poetry class

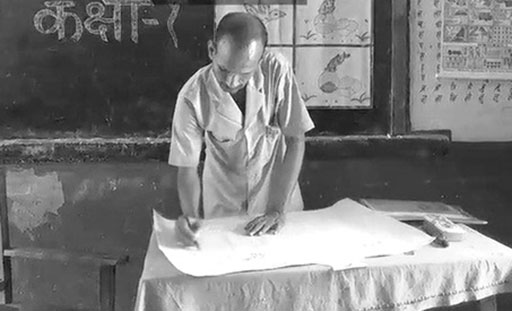

Mr Acharya works in a small school outside Gorakhpur. His Class VIII students’ writing abilities span very differing levels. Here he describes how he used pair work to support their poetry writing.

My students had been reading aloud some contemporary poems by Arun Kolatkar and Amit Chaudhuri. They had already written some poems on their own. This time I decided to get them to do so in pairs.

I chose a topic that I thought they could identify with: arguments with friends. I introduced the topic by asking the whole class some questions. These included:

- ‘When was your last disagreement with a friend?’

- ‘Was it a minor argument or a big one?’

- ‘How did you feel about it?’

- ‘Was the disagreement resolved?’

- ‘If so, how did that happen? How long did it take?’

- ‘If not, do you still expect it to be resolved?’

- ‘Is your friendship the same now as before?’

The topic generated a lot of discussion, with many students contributing to it. I wrote some of the words and phrases they used on the board, so they could draw on these in their writing.

Next, I told them that they were going to work in pairs and write a poem called ‘The Argument’. I organised the pairs by asking my students to work with the person next to them. I explained that they should take turns to make up a line of the poem at a time, noting it down as they went. After 30 minutes, I asked a volunteer from each pair to read out their completed – or partially completed – poem.

Here is a poem that one of the pairs wrote:

‘The Argument’

I had an argument with my friend Amvi

We were near a temple when she said something to an old man

He was poor and dirty

But my friend was unkind to him

I said she was wrong to say what she did

She said she didn’t care

I felt sorry for the man

I walked away alone

The poems that my students produced were about situations and feelings that they had experience and an understanding of. The pair talk helped them to share their ideas and consider how to capture them in writing.

When I use pair work, I keep the activities quite short, so that my students are less concerned with whom they have been placed with and more focused on completing the task within the allocated time. I notice, however, that they have quickly become used to working in this way.

Pause for thought

|

In the next case study, a teacher organises paired dialogues to support a writing task.

Case Study 2: The mongoose and the cobra

Ms Anju teaches in a school in Bihar Sharif. Here she describes a pair activity that she undertook with her Class VI students.

My students had been learning about native animals. They knew that mongooses eat insects, birds, earthworms, snakes, lizards and crabs. They are very quick. Their thick coats give them resistance to snake venom. They knew that cobras can spread their necks to produce a wide, flat hood. This, with a hissing sound, is their warning system when they are threatened. They mainly eat other snakes, small animals and birds.

I planned a language lesson linked to this topic. I started by asking my students what they recalled about the appearance and lives of mongooses and cobras. My questions included:

- ‘What do they look like?’

- ‘What do they eat?’

- ‘How might they react when they meet?’

I wrote key words on the board, such as ‘quick’, ‘hiss’, ‘coat’, ‘warning’ and ‘venom’. This first part of the lesson took 15 minutes.

Next I told my students to work with the person next to them. I asked them to decide which one was a cobra and which one was a mongoose, and think about what they might say to each other if they met in the forest. I gave them 15 minutes to improvise a dialogue between the two creatures, using different voices together with gestures and actions, if they wished. Some students preferred to use their home language or a mix of their home language and the school language for the dialogue. As they worked, I monitored them and continued to write key words on the board at their request. Many students were talking very animatedly.

Then I asked pairs of students to volunteer to come to the front of the class to perform their role plays. I tried to encourage some of the shyer ones too. The other students listened attentively and clapped after each performance. When the dialogue was in one of their home languages, I invited the rest of the class to help translate it into the school language afterwards. I allowed 30 minutes for the presentations.

To finish, I asked the pairs of students to write down their dialogue in their exercise books, illustrating it if they wished. I gave them 15 minutes for this final task.

Pause for thought

|

Pair work offers many opportunities for monitoring and assessing one’s students. Monitoring might involve:

- moving around class, observing and listening

- checking that everyone understands the instructions and is working as intended

- taking note of those students who are collaborating well or not so well

- giving praise, support and encouragement

- identifying common errors.

Assessment in turn could relate to the students’ language development, such as:

- their use of an appropriate range of vocabulary and expressions when speaking in their home or the school language

- their ability to translate this into writing

- the nature of their contribution to the pair collaboration

- their imagination

- their ability to perform to their classmates.

The key resource ‘Assessing progress and performance’ suggests additional ways of assessing your students in class.

Video: Assessing progress and performance |

3 Planning a pair work lesson

Now try Activity 2

Activity 2: Planning a pair work lesson

In this activity you will plan a lesson that incorporates no more than 20 minutes of pair work. Review the example task types in Resource 1:

- think–pair–share

- sharing information

- practising skills such as listening

- following instructions

- storytelling or role play.

Using the ideas and guidance in Resource 1 and drawing on Case Studies 1 and 2, choose a topic that your students will be motivated to talk and write about. You could base it on a chapter in the class language and literacy textbook or that of another subject, a recent event in the community, or a local or national news item. Consider what your students could read for inspiration before the pair work, or what reading opportunities there might be after it.

It is important to prepare your class carefully at the start.

- Explain to the students what they will be doing before you organise them into pairs.

- Demonstrate with the help of a volunteer exactly what they are expected to do.

- Call on a few students to explain this back to you to check their understanding. They can provide this explanation in their home language if they prefer.

- Model a quiet voice for talking in pairs. You should nevertheless accept that a certain level of noise in the class is a sign of your students’ engagement in the task.

- Set a clear time limit for the activity. Agree a signal, using your hands or a bell, to indicate when your students should stop.

- Pair your students. Think about how to do this in advance, ensuring that no one dominates nor is dominated by their partner within a pairing.

- Direct the pairs into different parts of the room if possible, or move some of them outside.

- Plan one or two additional activities for those pairs who finish early.

- Monitor your students as they work, listening to and observing them in their pairs and helping them where required.

- Select a small number of students and assess their use of language during the activity, with the aim of assessing others in future lessons.

- Allow time to give your class feedback and, if appropriate, for a few students to share their work at the end of the lesson or the following day. The act of presenting their work and listening to what others have done provides students with valuable additional learning opportunities, as does reading one another’s written work.

Activity 3: The advantages and disadvantages of pair work

After you have tried out your pair work activity, review how it went. Talk to a colleague about your experience if you can. Tick any of the statements in Table 1 that applied and add any further statements of your own.

| Benefits of pair work | Problems of pair work | ||

| Allows for much more student talking time in the classroom than in a ‘traditional’ lesson | Students are not used to working in pairs and require a lot of support with this | ||

| Encourages sociable learning and cooperation – with the possibility of making positive connections between students who don’t know each other well | Pairs may talk about other things instead of the task they’ve been assigned | ||

| Encourages a variety of imaginative outputs for the same task | High noise levels | ||

| Allows me to monitor and support students as they work | Partners don’t always get on with each other | ||

| Pairs have different finishing times | |||

| Requires a lot of teacher concentration and oversight | |||

|

|||

|

|||

Some of the problems you may have experienced can be reduced by explaining the benefits of working in pairs to your students, perhaps in their home language, and by gradually familiarising them with this way of working. Plan the pairings that would be most supportive before each lesson, adapting them in accordance with your observations and to maintain a variety of working patterns. You may also invite your students’ views – positive and negative – about pair work, but it is important to handle such discussions sensitively.

4 Summary

This unit has focused on ways of planning and managing pair work in your language lessons. By providing opportunities for sociable, collaborative learning in many different types of activity, pair work can be a very effective tool in your teaching repertoire.

Resources

Resource 1: Using pair work

In everyday situations people work alongside, speak and listen to others, and see what they do and how they do it. This is how people learn. As we talk to others, we discover new ideas and information. In classrooms, if everything is centred on the teacher, then most students do not get enough time to try out or demonstrate their learning or to ask questions. Some students may only give short answers and some may say nothing at all. In large classes, the situation is even worse, with only a small proportion of students saying anything at all.

Why use pair work?

Pair work is a natural way for students to talk and learn more. It gives them the chance to think and try out ideas and new language. It can provide a comfortable way for students to work through new skills and concepts, and works well in large classes.

Pair work is suitable for all ages and subjects. It is especially useful in multilingual, multi-grade classes, because pairs can be arranged to help each other. It works best when you plan specific tasks and establish routines to manage pairs to make sure that all of your students are included, learning and progressing. Once these routines are established, you will find that students quickly get used to working in pairs and enjoy learning this way.

Tasks for pair work

You can use a variety of pair work tasks depending on the intended outcome of the learning. The pair work task must be clear and appropriate so that working together helps learning more than working alone. By talking about their ideas, your students will automatically be thinking about and developing them further.

Pair work tasks could include:

- ‘Think–pair–share’: Students think about a problem or issue themselves and then work in pairs to work out possible answers before sharing their answers with other students. This could be used for spelling, working through calculations, putting things in categories or in order, giving different viewpoints, pretending to be characters from a story, and so on.

- Sharing information: Half the class are given information on one aspect of a topic; the other half are given information on a different aspect of the topic. They then work in pairs to share their information in order to solve a problem or come to a decision.

- Practising skills such as listening: One student could read a story and the other ask questions; one student could read a passage in English, while the other tries to write it down; one student could describe a picture or diagram while the other student tries to draw it based on the description.

- Following instructions: One student could read instructions for the other student to complete a task.

- Storytelling or role play: Students could work in pairs to create a story or a piece of dialogue in a language that they are learning.

Managing pairs to include all

Pair work is about involving all. Since students are different, pairs must be managed so that everyone knows what they have to do, what they are learning and what your expectations are. To establish pair work routines in your classroom, you should do the following:

- Manage the pairs that the students work in. Sometimes students will work in friendship pairs; sometimes they will not. Make sure they understand that you will decide the pairs to help them maximise their learning.

- To create more of a challenge, sometimes you could pair students of mixed ability and different languages together so that they can help each other; at other times you could pair students working at the same level.

- Keep records so that you know your students’ abilities and can pair them together accordingly.

- At the start, explain the benefits of pair work to the students, using examples from family and community contexts where people collaborate.

- Keep initial tasks brief and clear.

- Monitor the student pairs to make sure that they are working as you want.

- Give students roles or responsibilities in their pair, such as two characters from a story, or simple labels such as ‘1’ and ‘2’, or ‘As’ and ‘Bs’). Do this before they move to face each other so that they listen.

- Make sure that students can turn or move easily to sit to face each other.

During pair work, tell students how much time they have for each task and give regular time checks. Praise pairs who help each other and stay on task. Give pairs time to settle and find their own solutions – it can be tempting to get involved too quickly before students have had time to think and show what they can do. Most students enjoy the atmosphere of everyone talking and working. As you move around the class observing and listening, make notes of who is comfortable together, be alert to anyone who is not included, and note any common errors, good ideas or summary points.

At the end of the task you have a role in making connections between what the students have developed. You may select some pairs to show their work, or you may summarise this for them. Students like to feel a sense of achievement when working together. You don’t need to get every pair to report back – that would take too much time – but select students who you know from your observations will be able to make a positive contribution that will help others to learn. This might be an opportunity for students who are usually timid about contributing to build their confidence.

If you have given students a problem to solve, you could give a model answer and then ask them to discuss in pairs how to improve their answer. This will help them to think about their own learning and to learn from their mistakes.

If you are new to pair work, it is important to make notes on any changes you want to make to the task, timing or combinations of pairs. This is important because this is how you will learn and how you will improve your teaching. Organising successful pair work is linked to clear instructions and good time management, as well as succinct summarising – this all takes practice.

Additional resources

- Some helpful websites referring to paired reading:

- http://www.readingrockets.org/ strategies/ paired_reading

- http://www.moray.gov.uk/ moray_standard/ page_62204.html

- Some helpful websites referring to paired work in the classroom:

- http://www.teachingenglish.org.uk/ language-assistant/ primary-tips/ working-pairs-groups

References

Acknowledgements

This content is made available under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike licence (http://creativecommons.org/ licenses/ by-sa/ 3.0/), unless identified otherwise. The licence excludes the use of the TESS-India, OU and UKAID logos, which may only be used unadapted within the TESS-India project.

Every effort has been made to contact copyright owners. If any have been inadvertently overlooked the publishers will be pleased to make the necessary arrangements at the first opportunity.

Video (including video stills): thanks are extended to the teacher educators, headteachers, teachers and students across India who worked with The Open University in the productions.