Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Thursday, 5 February 2026, 9:24 AM

TI-AIE: Integrating language, literacy and subject learning

What this unit is about

Learning in school is usually divided into discrete curriculum subjects that are timetabled as a self-contained series of lessons. Language and literacy is usually treated as a distinct subject in this way, tending as it does to focus on the skills of reading and writing independent of other curriculum areas. But language and literacy are threaded through the learning and teaching of all curriculum subjects. When you teach environmental science, for instance, you are introducing your students to the concepts and vocabulary associated with that subject, and involving them in listening, speaking, reading and writing as they learn about it.

This unit aims to raise your awareness of integrated learning, and will guide you in planning activities that combine the acquisition of subject content with the development of language and literacy in the elementary classroom.

What you can learn in this unit

- How to plan and implement lessons that integrate subject-related learning and language and literacy-related learning.

- How to engage your students in collaborative, purposeful groupwork.

Why this approach is important

Language and literacy skills are essential to learning about all subjects taught in school. Students internalise knowledge by listening, talking, reading and writing and by understanding and employing the specific terms, phrases and structures that are associated with particular topics.

In science, for instance, lessons in which students plan, predict, observe, record, describe, explain and summarise will promote not only their learning of the subject but also their language and literacy development. All school subjects offer such language and literacy development opportunities. The ability to integrate these complementary aspects of learning – subject-related content and language and literacy content – is the characteristic of a skilled teacher.

1 Combining subject-related teaching and language and literacy development in the primary classroom

You will start by reading a case study of a teacher who teaches astronomy and language and literacy development at the same time.

Case Study 1: Teaching astronomy

Mrs Meena teaches all subjects to her Class III students in a government school in Varana. Here she describes her integrated approach towards such subject teaching in her classroom.

My students are curious about the Sun, the Moon and the stars, and often talk about them. Many of them like to draw pictures of themselves in spacesuits or of imaginary people from different planets. Earlier this year I planned a series of lessons to develop this interest. I thought carefully about the topic and its associated language.

I started with a game to help my students remember the names of the planets in their order of distance from the Sun. In the next lesson, I then organised my class into 11 groups and gave them the following names: ‘Sun’, ‘Moon’, ‘Earth’, ‘Venus’, ‘Mars’, ‘Jupiter’, ‘Mercury’, ‘Saturn’, ‘Neptune’, ‘Pluto’ and ‘Uranus’. I handed each group a science textbook and asked my students to find a picture of their respective planet or moon, and look up whatever information they could find about it. I wrote some questions on the blackboard as prompts, such as:

- What colour is your planet?

- How far is it from the Sun?

- Can people live there?

- Why, or why not?

I explained that when they had finished, they would each share one fact on their allocated planet or moon with the rest of the class. They could do this from memory or by reading it out the information from the book or their notes.

As my students worked, I walked around the classroom, listening to and observing them, monitoring their developing understanding of astronomy alongside their language and literacy skills. I encouraged the stronger readers within each group to help those who were less confident and was pleased with the supportive way they did this.

In a subsequent lesson, I invited the class to play ‘Twenty Questions’ about one of the planets or moons. I demonstrated the game first and then directed my students to continue play it in groups of eight. Finally, I asked my students to write a paragraph in their exercise books describing themselves as a planet, and to illustrate it with a drawing. My students seemed to enjoy this series of topic-related activities, perhaps because they involved lots of groupwork and combined a variety of elements and skills.

Whenever I can, I try to plan lessons that develop my students’ understanding of a particular subject, like geography or history, alongside their language and literacy skills. I usually begin by giving groups of students some information to read before they report back to the class. If I can think of games to test their knowledge, I use these too. I generally give them a writing task at the end to consolidate their learning. I normally spread these integrated activities over two or three lessons.

Pause for thought

|

Read Resource 1, ‘Using groupwork’, to learn more about organising students for collaborative groupwork.

Activity 1: Integrated learning objectives

Resource 2 outlines two different lessons that integrate subject learning with language and literacy development. One lesson integrates mathematical language, the properties of shapes, groupwork, movement and writing; the other lesson integrates art, science, poetic language, pair work and writing. Both sets of activities are adaptable for either younger or older students. Both require very few resources.

With a colleague if possible, begin by reading ‘Lesson 1: Mathematics, shape, movement and language’. Then discuss the following questions:

- Before doing the series of activities described in Lesson 1, what would your students need to know about:

- mathematics?

- reading?

- writing?

- working together?

- How could the activities extend or reinforce your students’ prior learning in mathematics, physical education or language and literacy?

Now read ‘Lesson 2: The planets, colours and poetic language’. Then consider the questions that follow.

- Before doing the series of activities described in Lesson 2, what would your students need to know about:

- planets?

- writing?

- poetry?

- art?

- peer support?

- How could this activity extend or reinforce your students’ prior learning in science, art or language and literacy?

Look ahead in your textbook to a subject lesson that you are going to teach. Identify opportunities to integrate language and literacy work alongside the subject content. Consider which of the activities would be best suited to groupwork. Discuss your ideas with a colleague.

If you have not tried an integrated approach like this before, what do you think you will find most challenging? How might you address these challenges?

When you have implemented the lesson, reflect on what you learnt from this way of teaching. What learning took place on the part of your students? How could you tell?

2 Combining language and literacy development with a more challenging subject

In the next case study you will read how a teacher supported his students in acquiring the language associated with a more challenging subject area.

Case Study 2: Language and science

Mr Rahul teaches Class VI in a large school in Jabalpur. Here he describes how he introduced his students to the more complex scientific terms used in the field of botany.

The next chapter in our textbook was about the study of plants. I knew that both the scientific concepts and the vocabulary would be difficult for my class. I therefore planned a series of lessons that combined learning about the subject and the specialised language it employed.

On Day 1, I introduced my students to the topic in the textbook and asked them questions to find out what they knew about plants already. I then asked my students to read a section of the chapter in turn. Partly because of the new terminology and partly because the topic was presented very theoretically. This proved to be quite a challenge for them. After they read each section, I rephrased it using simpler terms, and drew some accompanying illustrations on the blackboard to facilitate their understanding.

On Day 2, I organised my class into eight groups of six students, took them outside and gave them time to look at different plants in the school grounds. I explained to them the difference between seeing a plant and observing it. I assigned a task to each group. Two groups observed the height, stems and branching of the plants that they saw. Two groups examined the shape and structure of different types of leaves. Two groups observed the many parts of flowers. The last two groups pulled up some weeds in order to study the parts of these plants that were underground.

I encouraged my students to draw sketches of what they observed in their exercise books, comparing their ideas within their groups as they did so. I supported and guided them as they worked. They seemed to be very absorbed in this outdoor collaborative activity.

On Day 3 my students labelled their drawings, using their textbook to check the correct terms. As they did this, they started to use the specialised botanical language associated with the subject.

On Day 4, the groups prepared and gave short presentations on their observations to the rest of the class, using the terminology they had learnt and illustrating their talks with their drawings. Sometimes I prompted them by asking questions such as ‘How are climbers different from shrubs?’ I invited the rest of the class to ask those presenting questions, too.

I noticed that the practical outdoor activity that followed my students’ initial reading of the textbook greatly enhanced their understanding of the new concepts in the chapter and motivated them to engage with its associated terminology. Preparing to give a presentation helped to clarify and consolidate their learning, as did the talk that accompanied the group activities.

Pause for thought With a colleague, consider the learning outcomes of Mr Rahul’s series of activities:

|

In these activities, the students learn both the everyday and the scientific terms for plants, and they are able to apply that language to plants that they find in their local environment. This consolidates their learning and makes it meaningful. They have to work together to describe the plants and present the information they have collated to the rest of the class.

Mr Rahul starts this series of lessons by asking his students what they already know about plants. Read the key resource ‘Using questioning to promote thinking’ to find out more about this classroom technique.

Activity 2: Integrating subject vocabulary into a lesson

Look ahead to the next subject lesson you are going to teach and identify the vocabulary that is specific to the subject.

Plan an enjoyable speaking, listening reading or writing activity in which your students will practise using this vocabulary. You do not need to plan four lessons as Mr Rahul did. Start by planning one lesson, building on your students’ previous learning of the subject as you do so. Share your ideas with your colleagues.

3 Summary

In this unit you have read some examples of how teachers integrate subject teaching and language and literacy development in their classrooms. You have looked ahead at a subject-based textbook chapter and considered ways of combining language and literacy-related activities alongside its content.

Teachers tend to view language and literacy classes as being separate from other areas of the curriculum. However, there are many benefits to integrating language and literacy activities into different subject lessons. Group-based collaborative activities are particularly valuable in providing students with opportunities to practise and assimilate new subject-related concepts and language.

Resources

Resource 1: Using groupwork

Groupwork is a systematic, active, pedagogical strategy that encourages small groups of students to work together for the achievement of a common goal. These small groups promote more active and more effective learning through structured activities.

The benefits of groupwork

Groupwork can be a very effective way of motivating your students to learn by encouraging them to think, communicate, exchange ideas and thoughts, and make decisions. Your students can both teach and learn from others: a powerful and active form of learning.

Groupwork is more than students sitting in groups; it involves working on and contributing to a shared learning task with a clear objective. You need to be clear about why you are using groupwork for learning and know why this is preferable to lecturing, pair work or to students working on their own. Thus groupwork has to be well-planned and purposeful.

Planning groupwork

When and how you use groupwork will depend on what learning you want to achieve by the end of the lesson. You can include groupwork at the start, the end or midway through the lesson, but you will need to allow enough time. You will need to think about the task that you want your students to complete and the best way to organise the groups.

As a teacher, you can ensure that groupwork is successful if you plan in advance:

- the goals and expected outcomes of the group activity

- the time allocated to the activity, including any feedback or summary task

- how to split the groups (how many groups, how many students in each group, criteria for groups)

- how to organise the groups (role of different group members, time required, materials, recording and reporting)

- how any assessment will be undertaken and recorded (take care to distinguish individual assessments from group assessments)

- how you will monitor the groups’ activities.

Groupwork tasks

The task that you ask your students to complete depends on what you what them to learn. By taking part in groupwork, they will learn skills such as listening to each other, explaining their ideas and working cooperatively. However, the main aim is for them to learn something about the subject that you are teaching. Some examples of tasks could include the following:

- Presentations: Students work in groups to prepare a presentation for the rest of the class. This works best if each group has a different aspect of the topic, so they are motivated to listen to each other rather than listening to the same topic several times. Be very strict about the time that each group has to present and decide on a set of criteria for a good presentation. Write these on the board before the lesson. Students can the use the criteria to plan their presentation and assess each other’s work. The criteria could include:

- Was the presentation clear?

- Was the presentation well-structured?

- Did I learn something from the presentation?

- Did the presentation make me think?

- Problem solving: Students work in groups to solve a problem or a series of problems. This could include conducting an experiment in science, solving problems in mathematics, analysing a story or poem in English, or analysing evidence in history.

- Creating an artefact or product: Students work in groups to develop a story, a piece of drama, a piece of music, a model to explain a concept, a news report on an issue or a poster to summarise information or explain a concept. Giving groups five minutes at the start of a new topic to create a brainstorm or mind map will tell you a great deal about what they already know, and will help you pitch the lesson at an appropriate level.

- Differentiated tasks: Groupwork is an opportunity to allow students of different ages or attainment levels to work together on an appropriate task. Higher attainers can benefit from the opportunity to explain the work, whereas lower attainers may find it easier to ask questions in a group than in a class, and will learn from their classmates.

- Discussion: Students consider an issue and come to a conclusion. This may require quite a bit of preparation on your part in order to make sure that the students have enough knowledge to consider different options, but organising a discussion or debate can be very rewarding for both you and them.

Organising groups

Groups of four to eight are ideal but this will depend on the size of your class, the physical environment and furniture, and the attainment and age range of your class. Ideally everyone in a group needs to see each other, talk without shouting and contribute to the group’s outcome.

- Decide how and why you will divide students into groups; for example, you may divide groups by friendship, interest or by similar or mixed attainment. Experiment with different ways and review what works best with each class.

- Plan any roles you will give to group members (for example, note taker, spokesperson, time keeper or collector of equipment), and how you will make this clear.

Managing groupwork

You can set up routines and rules to manage good groupwork. When you use groupwork regularly, students will know what you expect and find it enjoyable. Initially it is a good idea to work with your class to identify the benefits of working together in teams and groups. You should discuss what makes good groupwork behaviour and possibly generate a list of ‘rules’ that might be displayed; for example, ‘Respect for each other’, ‘Listening’, ‘Helping each other’, ‘Trying more than one idea’, etc.

It is important to give clear verbal instructions about the groupwork that can also be written on the blackboard for reference. You need to:

- direct your students to the groups they will work in according to your plan, perhaps designating areas in the classroom where they will work or giving instructions about moving any furniture or school bags

- be very clear about the task and write it on the board in short instructions or pictures. Allow your students to ask questions before you start.

During the lesson, move around to observe and check how the groups are doing. Offer advice where needed if they are deviating from the task or getting stuck.

You might want to change the groups during the task. Here are two techniques to try when you are feeling confident about groupwork – they are particularly helpful when managing a large class:

- ‘Expert groups’: Give each group a different task, such as researching one way of generating electricity or developing a character for a drama. After a suitable time, re-organise the groups so that each new group is made up of one ‘expert’ from all the original groups. Then give them a task that involves collating knowledge from all the experts, such as deciding on what sort of power station to build or preparing a piece of drama.

- ‘Envoys’: If the task involves creating something or solving a problem, after a while, ask each group to send an envoy to another group. They could compare ideas or solutions to the problem and then report back to their own group. In this way, groups can learn from each other.

At the end of the task, summarise what has been learnt and correct any misunderstandings that you have seen. You may want to hear feedback from each group, or ask just one or two groups who you think have some good ideas. Keep students’ reporting brief and encourage them to offer feedback on work from other groups by identifying what has been done well, what was interesting and what might be developed further.

Even if you want to adopt groupwork in your classroom, you may at times find it difficult to organise because some students:

- are resistant to active learning and do not engage

- are dominant

- do not participate due to poor interpersonal skills or lack of confidence.

To become effective at managing groupwork it is important to reflect on all the above points, in addition to considering how far the learning outcomes were met and how well your students responded (did they all benefit?). Consider and carefully plan any adjustments you might make to the group task, resources, timings or composition of the groups.

Research suggests that learning in groups need not be used all the time to have positive effects on student achievement, so you should not feel obliged to use it in every lesson. You might want to consider using groupwork as a supplemental technique, for example as a break between a topic change or a jump-start for class discussion. It can also be used as an ice-breaker or to introduce experiential learning activities and problem solving exercises into the classroom, or to review topics.

Resource 2: Two lessons

Lesson 1: Mathematics, shape, movement and language

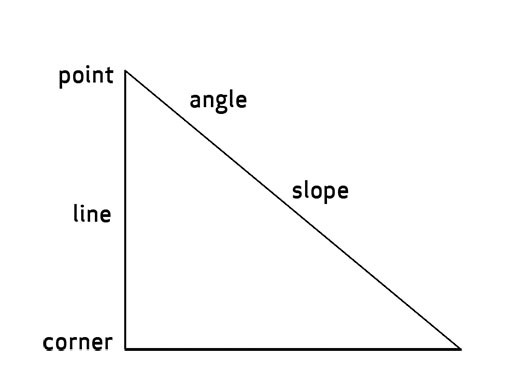

The language of shape is rich in mathematical terms and concepts. ‘Edge’, ‘plane’, ‘line’, ‘parallel’, ‘depth’, ‘angle’, ‘volume’, ‘point’ and ‘segment’ are just a sample of the many terms associated with shapes. The complexity of the shapes you use in this activity will depend on the age and prior knowledge of your class. For this activity, you will need some mathematics textbooks.

- Divide your class into groups. Give each group a name of a shape, such as ‘Square’, ‘Rectangle’, ‘Triangle’, ‘Circle’, ‘Trapezium’, ‘Rhombus’, ‘Pentagram’, ‘Octagon’, ‘Oval’ or ‘Parallelogram’. You can give the same name to more than one group. Give each group a mathematics textbook.

- Model to your class what you expect them to do. Locate information about an example shape in the textbook. Then describe the shape to the class, beginning with the words ‘I am a [shape]’ and using the correct mathematical terms.

- Ask each group to find information about their shape in their textbook. They can remember the information or make notes about it on chart paper.

- Invite each group to present their shape to the rest of the class. Encourage them to use the appropriate language in describing it, for instance: ‘We are the rectangle. We have four straight sides but two sides are longer than the other two. The sides are parallel.’

- Get each group to physically form their shape by standing together and linking hands. They can do this in the classroom or possibly outside, where there is more space.

- Ask each student to draw both their shape and a different shape from another group, writing words in and around each one based on what that they have read or heard you or other students say. An example is provided in Figure R2.1.

Lesson 2: The planets, colours and poetic language

The natural colours and patterns of the planets are all different and quite beautiful. The language you use in this activity will depend on the ages and backgrounds of your students. For this activity, you will need photos or drawings of planets, or coloured chalk.

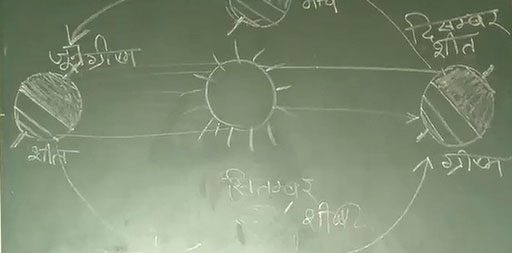

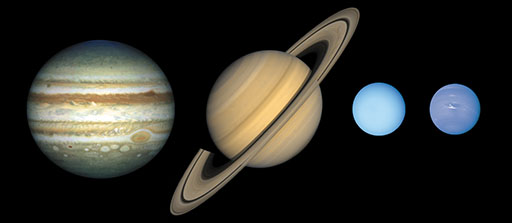

- Use good-quality pictures or drawings of the planets, if you have them, or alternatively, use coloured chalk to draw them on the blackboard (Figure R2.2). Show these images to your class, describing the colours and patterns of the planets to in detail. Invite your students to talk about any planets they have either observed themselves or know about from their reading.

- Introduce the idea of the planets as having different ‘personalities’ or ‘qualities’. For example, with its pale blue and brown colouring, Jupiter appears ‘calm’; light-brown Saturn seems ‘sleepy’; orangey-red Mars could either be ‘fiery’ and ‘angry’, or ‘warm’; the Sun could be ‘cheerful’, but it could also be ‘explosive’ and ‘too dangerous to approach’. Encourage your students to make suggestions for each planet, noting down their ideas on the blackboard.

- Ask each student to choose two planets and draw and colour them carefully in their exercise books (Figure R2.3). Get them to write a paragraph or a poem about their planet as if it had personal qualities. Invite them to read out their paragraph to their partner and then to the rest of the class.

Additional resources

- ‘Language across curriculum’ by Nisha Butoliya: http://www.teachersofindia.org/ en/ lesson-plan/ language-across-curriculum

- ‘Revisiting school education In India – National Curriculum Framework 2005: focus on language’ by V.K. Sunwani: http://www.languageinindia.com/ sep2006/ nationalframework.html

- An idea for teaching about stars: https://www.academia.edu/ 4306703/ Jewels_in_the_Sky

- ‘Preparing for group work’: https://thinkingtogether.educ.cam.ac.uk/ resources/ downloads/ Preparing_for_group_work.pdf

- Elearning ideas for a variety of subject areas: http://www.azimpremjifoundation.org/ E-learning_Resources

- You may find useful resources at this government website: http://nroer.gov.in/ collection/ Audio/

References

Acknowledgements

Except for third party materials and otherwise stated below, this content is made available under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike licence (http://creativecommons.org/ licenses/ by-sa/ 3.0/). The material acknowledged below is Proprietary and used under licence for this project, and not subject to the Creative Commons Licence. This means that this material may only be used unadapted within the TESS-India project and not in any subsequent OER versions. This includes the use of the TESS-India, OU and UKAID logos.

Grateful acknowledgement is made to the following sources for permission to reproduce the material in this unit:

Figure R2.3: Nasa (in Flickr) (adapted), made available by NASA under https://creativecommons.org/ licenses/ by/ 2.0/ deed.en

Every effort has been made to contact copyright owners. If any have been inadvertently overlooked the publishers will be pleased to make the necessary arrangements at the first opportunity.

Video (including video stills): thanks are extended to the teacher educators, headteachers, teachers and students across India who worked with The Open University in the productions.