Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Thursday, 5 February 2026, 5:30 AM

TI-AIE: Community approaches: science education and environmental issues

What this unit is about

Community approaches to science education focus on relating the accepted science concepts and facts to the problems facing society. They will help your students to understand the causes and consequences of environmental problems at local, national and global levels. This approach to science education is also called science, technology, society and environment (STSE) education.

In this approach, the students are encouraged to understand issues that impact on everyday life and make responsible decisions about how to address such issues. You will learn techniques to increase your students’ abilities to link scientific theories to contemporary issues such as the development and use of genetically modified (GM) crops. The aim is to help your students become informed citizens in a democratic society.

This unit will help you to develop strategies that you can use in your classroom to promote informed discussion about these important contemporary issues.

What you can learn in this unit

- The benefits of a ‘community-based approach’.

- A range of strategies for relating social, technological, economic and environmental issues to the science topics you are teaching.

- How to organise group discussions in your classroom.

Why this approach is important

The National Curriculum Framework (2005) states that science education in India should help students to become more aware of their environment and the importance of protecting it for future generations.

Pause for thought

|

There are two main arguments for this approach to science education (Osborne, 2010) that the Government might have considered:

- The economic argument. A country with a growing economy needs a constant supply of scientists to remain internationally competitive. Scientists can work on solutions to environmental and health issues, and generate evidence to inform policy.

- The democratic argument. Many of the problems facing society are complex and the solution often depends on science as well as economics and politics. A strong democracy is one in which citizens are well-informed, appreciate the importance of considering multiple viewpoints and take an active part in democratic processes.

The implications for you are that your students should understand that studying science at school is important even if they don’t want to study science after school. By raising their awareness and understanding of complex science issues, you are educating your students to take part in democracy as well as potentially contribute to economic development.

1 Making links between environmental and social issues and the curriculum

In your textbook the chapters covering the social, technological and environmental aspects of science are often at the back of the book, and the textbook does not always make clear the links between the issues and the science ideas.

One way to make your students more interested in science is to integrate social and environmental issues into your teaching in every topic. You need to develop the habit of asking yourself ‘How is this topic relevant to my students’ lives?’

You can get ideas from newspapers, news bulletins and magazines, and you can develop an awareness of local, national and global issues.

Activity 1: Making links

This activity is for you to do on your own or with other teachers. You will need access to a textbook that was written after 2005.

The activity is split into two separate parts. It will help you to raise your awareness about how social and environmental issues link to the science curriculum.

Part 1: Gathering ideas from the news

Watch the news on television, listen to a radio bulletin, find a newspaper or find a news website on the internet. Make a list of news items that have some basis in science that is relevant to the Secondary Science curriculum.

Put any articles you find in a file that you can refer to later.

Part 2: Linking the issues to the science

Look at the last three chapters of the textbook. This is where you will find information about ‘natural resources’, ‘food resources’ or ‘our environment’. Rather than study these chapters at the end of the year when you are running out of time, think about how you could make connections between the issues in the last three chapters and the appropriate science topics.

Copy and complete Table 1.

| Science topic | Environmental issue |

|---|---|

| Organic chemistry – hydrocarbons | Biodegradable and non-biodegradable rubbish |

| Plant tissues | Crop production management |

| Water supplies | |

| Water pollution | |

| Supplies and use of fossil fuels | |

| Pesticides in food chains | |

| Damage to the ozone layer | |

When you are teaching each of the science topics you will need to remember to spend some time studying the related environmental issues. This will make it more interesting for your students and enable them to use their science knowledge and understanding to take part in informed discussions and make decisions about the issues.

Pause for thought

|

The sorts of things you might have thought of could include: water supply, water pollution, air pollution, farming methods, electricity generation, healthcare and food supply, although there will certainly be many more.

Once you are familiar with the social and environmental issues that relate to science, you can bring them into your teaching without taking too much extra time. In Case Study 1, a teacher describes how she did this with her class.

Case Study 1: Relating a news item to a medical issue

Mrs Verma describes how she used a news item to highlight a social issue related to the study of the kidney.

One weekend I went to see the film, The Ship of Theseus. It was quite upsetting and it got me thinking about organ donation. I remembered that in my file I had a newspaper article about a young labourer who was desperate for money. He had been persuaded to donate one of his kidneys for a lot of money. Because it is illegal to sell organs in this way, he did not go to a proper hospital and he got a very bad infection. He had to spend most of the money on medicines.

On Monday I had to teach the kidney to Class X. We were studying ‘transportation’ in the chapter on ‘life processes’. I drew a diagram of a nephron on the blackboard and asked my students to look in their textbook to find the labels. We wrote about what the kidney does and how it works. I explained that although we have two kidneys, we can survive with one. I asked, ‘Does anyone know what happens if your kidneys do not work properly?’

Shanka told us that his uncle was very poorly and had to go to hospital for dialysis every week because he had kidney disease. Six months ago his cousin donated a kidney to him. Now he lives a normal life.

Then I read my students the newspaper article about the poor man who had been persuaded to sell his kidney. They were very interested in the case and a lot of them were quite cross. I asked my students, ‘Do you think organ donation is a good thing, bearing in mind what had happened to Shanka’s uncle and the poor labourer?’ I gave them a few minutes to talk to their neighbour about what they thought and why. I walked round and listened to their conversations. I then picked four students who seemed to have slightly different views to report back to the class.

Finally I told them about the film I had seen. Some of my students said they would like to see it, so I warned them that it is quite upsetting.

As they left the room they were still arguing about the issue. Mr Singh heard them in the corridor when he came out of his room and was surprised to hear students talking about a science lesson. He came to ask me what we had been doing and decided to try it himself. I lent him the newspaper article. After that we frequently exchanged ideas and resources.

Mrs Verma asked her students to talk to their neighbour. This sort of pair work has the advantage of taking very little time. In the next section, you will do an activity that involves groupwork.

2 Teaching community-based approaches

The science involved in social and environmental issues is often complicated. But don’t worry – you don’t need to be an expert. Your role is to help your students understand how to use their science knowledge to make responsible decisions in their own lives.

Also, it is important to remember that there are often no ‘right’ answers to some of the issues that you will raise. For example, ‘Which sort of power station should be built?’, ‘Should we support the development of genetically modified (GM) crops?’ and ‘Should we spend money on exploring the other planets in the solar system?’ All of these involve people developing convincing arguments to persuade others.

In science lessons you are preparing your students to be informed citizens and helping them to understand the underlying scientific principles. It is an opportunity for them to develop a wide range of skills.

Pause for thought

|

Informed citizens are able to process information, assess the validity of an argument, and take a critical approach to evidence. They are prepared to listen to different points of view. They respect the opinions of others and they are able to articulate their own view and support it with evidence. The teaching approaches described in the next section will help your students to develop these skills.

Group discussions

Small group discussions can result in high levels of participation. Group talk is important because it helps students to learn to reason. Learning to reason requires the ability to use the ideas and language of science to begin to construct arguments that link evidence and data to ideas and theories. Effective small group discussion requires students to justify the reasons for their beliefs.

But you need to plan effective group discussion. You need to be very clear about what you want students to discuss and what the outcome of their work is going to be. You will need to provide them with some prompts to get them going, and give them a sense of purpose.

Pause for thought

|

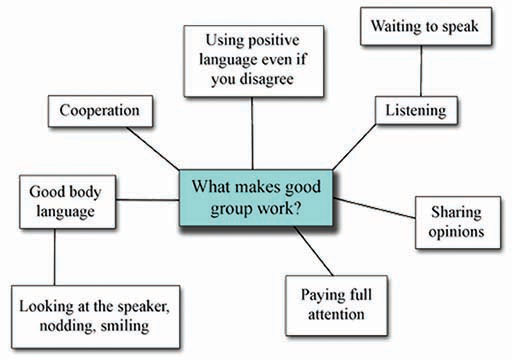

Have a look at Resource 1 on groupwork and compare your thoughts with the ideas given there. In order to have a successful group discussion, your students will need:

- some specific questions to discuss

- some background information on the topic

- a clear goal or purpose for the discussion.

Your students will need practice at working effectively in a group; they need to learn the skills required. Look at Resource 1 for more information on groupwork.

Case Study 2: Social issues linked to river pollution

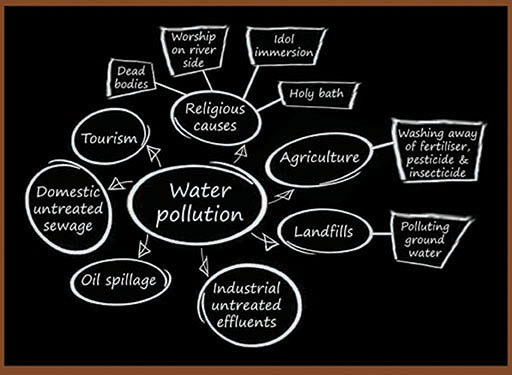

Mrs Verma wanted her students to be capable of dealing responsibly with social issues, specifically those that could be better understood with the help of science. She decided teach water pollution to her Class IX, by focusing on using social issues to initiate a classroom discussion. Read her account of her approach.

I asked my students to sit in their usual groups of four to six, and they quickly got themselves organised. They were sitting with people they had worked with in other science lessons. I chose these groups because I wanted them to have the confidence to say what they thought and bring out the issues.

Before writing the topic on the blackboard, I asked the students, ‘Can we go and drink water directly from Yamuna river in our city?’ Since news of the deteriorating condition of the Yamuna river water was a burning issue, most of the students replied in chorus, ‘No, it’s polluted.’ This confirmed to me how aware my students were and that we could proceed to discuss water pollution that day.

I provided each group with some pictures of people using the river for different activities. The pictures were downloaded from the internet but I did wonder if I might have hand-drawn them instead, especially as I did not find all the pictures I wanted.

I then wrote a key question on the blackboard: ‘How do these activities affect our water resources?’ I asked the students to note down whatever they discussed in their groups so that they could contribute these ideas to class discussion at a later stage.

I have found that with a large class, there are invariably very diverse viewpoints that are always interesting. The classroom was quite noisy as the groups discussed their pictures, and I moved around the groups to check that they did not become unruly. After giving them ten minutes I asked them to stop their discussions.

I then asked each group in turn to give me one idea and pointed from one group to another until there were no new ideas. This took another ten minutes. The students suggested many things that could have affected the river, such as: dead bodies being in the water, where they decay and contaminate it; untreated sewage of daily activities from whole cities flowing into it; pollution from chemicals; and, every year, thousands of idol immersions contaminating the water.

As they called out their ideas, I praised the groups and wrote them on the blackboard to show how concepts are grouped and connected [Figure 2]. Deciding where to put the ideas sometimes generated a discussion itself, such as whether pouring some old engine oil into the river was industrial effluent or domestic waste.

Once we had completed the representation of the various causes of water pollution, I moved the discussion on to focus on some more specific issues. I gave each group a piece of paper with one of the following statements and asked them to debate what was written on it:

- A river cannot purify itself where there is a high density of people, due to the large number of rituals that are performed. So the rituals should be limited.

- Religious beliefs are an integral part of our lives, but clean drinking water is a greater necessity of life.

- A single person’s actions have a cumulative impact on a whole society, and therefore on the entire ecology of the planet, so we should each act to stop pollution.

- Pollution comes about because of ignorance of long-term consequences, so education is the solution.

- A farmer can increase his yield by 50 per cent with chemical fertilisers, so any harm to the environment is less important.

- Industry provides jobs and prosperity. The fact that factories may pollute the river is less important than that.

I then asked them to vote within their group on whether they agreed with the statement or not. I stressed that it was OK to disagree, and that they should listen to one another’s views. Again there was a lot of loud discussion in the groups. I was particularly pleased to notice that Anju, who is not usually interested in science, had a great deal to say about the effect of religious ceremonies on the pollution in the river.

I clapped my hands when it was time to vote, and each group voted on their issue. They then read their statement out to the rest of the class and let us know what the voting results were, as well as the arguments for and against each statement.

It was good to hear my students continuing their discussions at the end of the lesson, as they left the room. I was pleased that they were so engaged with the topic and able to consider the science behind it.

I decided that some other time I would provide them with some scientific data (for example, about deaths from water-borne diseases, numbers of rituals per annum, annual volume of a single human’s waste, incidence of birth defects) to help their discussions.

Pause for thought Re-read the paragraph before the case study and reflect on the things that Mrs Verma did to ensure that the discussion was productive. |

Mrs Verma provided some background information in the form of some pictures of activities that affected the river. She gave her students a relatively easy thing to discuss first before moving on to the more specific and controversial questions. By the end of the lesson, the students should have had a good overview of the causes of water pollution and have realised that people need to take responsibility for their actions. Hopefully, some of them will be beginning to appreciate the challenge of how to control people’s behaviour and the importance of government structures in doing so.

3 Putting it into practice

Activity 2: Planning your own lesson

Think about what you have to teach in the next few weeks. Use the textbook to help you identify a relevant environmental or social issue. Some examples are given in Resource 2.

Plan a lesson similar to the one that Mrs Verma did.

- Think about how to divide your students into groups.

- Write a list of questions that they could discuss.

- Collect some relevant information that you could give to your students, or that you could write on the blackboard. This might involve going to a library or an internet café.

Teach the lesson to Class IX or Class X.

While the students are talking to each other, walk round the room and listen carefully to the discussions. Be prepared to ask a few questions to prompt them if necessary. Note down which students are contributing well and which seem to be quiet. You will be able to use this information next time you organise a discussion in order to decide how to organise the groups.

For more information on this, look at the key resource ‘Planning lessons’.

Pause for thought

|

4 Summary

Science is all around us, yet students often find it difficult to relate what they learn in science lessons to their everyday lives. Hopefully this unit has given you some ideas for making sure that you keep looking for ways to highlight the importance of science.

Running group discussions is difficult, but it will become easier with practice – for you and for your students.

Resources

Resource 1: Using groupwork

Groupwork is a systematic, active, pedagogical strategy that encourages small groups of students to work together for the achievement of a common goal. These small groups promote more active and more effective learning through structured activities.

The benefits of groupwork

Groupwork can be a very effective way of motivating your students to learn by encouraging them to think, communicate, exchange ideas and thoughts, and make decisions. Your students can both teach and learn from others: a powerful and active form of learning.

Groupwork is more than students sitting in groups; it involves working on and contributing to a shared learning task with a clear objective. You need to be clear about why you are using groupwork for learning and know why this is preferable to lecturing, pair work or to students working on their own. Thus groupwork has to be well-planned and purposeful.

Planning groupwork

When and how you use groupwork will depend on what learning you want to achieve by the end of the lesson. You can include groupwork at the start, the end or midway through the lesson, but you will need to allow enough time. You will need to think about the task that you want your students to complete and the best way to organise the groups.

As a teacher, you can ensure that groupwork is successful if you plan in advance:

- the goals and expected outcomes of the group activity

- the time allocated to the activity, including any feedback or summary task

- how to split the groups (how many groups, how many students in each group, criteria for groups)

- how to organise the groups (role of different group members, time required, materials, recording and reporting)

- how any assessment will be undertaken and recorded (take care to distinguish individual assessments from group assessments)

- how you will monitor the groups’ activities.

Groupwork tasks

The task that you ask your students to complete depends on what you what them to learn. By taking part in groupwork, they will learn skills such as listening to each other, explaining their ideas and working cooperatively. However, the main aim is for them to learn something about the subject that you are teaching. Some examples of tasks could include the following:

- Presentations: Students work in groups to prepare a presentation for the rest of the class. This works best if each group has a different aspect of the topic, so they are motivated to listen to each other rather than listening to the same topic several times. Be very strict about the time that each group has to present and decide on a set of criteria for a good presentation. Write these on the board before the lesson. Students can the use the criteria to plan their presentation and assess each other’s work. The criteria could include:

- Was the presentation clear?

- Was the presentation well-structured?

- Did I learn something from the presentation?

- Did the presentation make me think?

- Problem solving: Students work in groups to solve a problem or a series of problems. This could include conducting an experiment in science, solving problems in mathematics, analysing a story or poem in English, or analysing evidence in history.

- Creating an artefact or product: Students work in groups to develop a story, a piece of drama, a piece of music, a model to explain a concept, a news report on an issue or a poster to summarise information or explain a concept. Giving groups five minutes at the start of a new topic to create a brainstorm or mind map will tell you a great deal about what they already know, and will help you pitch the lesson at an appropriate level.

- Differentiated tasks: Groupwork is an opportunity to allow students of different ages or attainment levels to work together on an appropriate task. Higher attainers can benefit from the opportunity to explain the work, whereas lower attainers may find it easier to ask questions in a group than in a class, and will learn from their classmates.

- Discussion: Students consider an issue and come to a conclusion. This may require quite a bit of preparation on your part in order to make sure that the students have enough knowledge to consider different options, but organising a discussion or debate can be very rewarding for both you and them.

Organising groups

Groups of four to eight are ideal but this will depend on the size of your class, the physical environment and furniture, and the attainment and age range of your class. Ideally everyone in a group needs to see each other, talk without shouting and contribute to the group’s outcome.

- Decide how and why you will divide students into groups; for example, you may divide groups by friendship, interest or by similar or mixed attainment. Experiment with different ways and review what works best with each class.

- Plan any roles you will give to group members (for example, note taker, spokesperson, time keeper or collector of equipment), and how you will make this clear.

Managing groupwork

You can set up routines and rules to manage good groupwork. When you use groupwork regularly, students will know what you expect and find it enjoyable. Initially it is a good idea to work with your class to identify the benefits of working together in teams and groups. You should discuss what makes good groupwork behaviour and possibly generate a list of ‘rules’ that might be displayed; for example, ‘Respect for each other’, ‘Listening’, ‘Helping each other’, ‘Trying more than one idea’, etc.

It is important to give clear verbal instructions about the groupwork that can also be written on the blackboard for reference. You need to:

- direct your students to the groups they will work in according to your plan, perhaps designating areas in the classroom where they will work or giving instructions about moving any furniture or school bags

- be very clear about the task and write it on the board in short instructions or pictures. Allow your students to ask questions before you start.

During the lesson, move around to observe and check how the groups are doing. Offer advice where needed if they are deviating from the task or getting stuck.

You might want to change the groups during the task. Here are two techniques to try when you are feeling confident about groupwork – they are particularly helpful when managing a large class:

- ‘Expert groups’: Give each group a different task, such as researching one way of generating electricity or developing a character for a drama. After a suitable time, re-organise the groups so that each new group is made up of one ‘expert’ from all the original groups. Then give them a task that involves collating knowledge from all the experts, such as deciding on what sort of power station to build or preparing a piece of drama.

- ‘Envoys’: If the task involves creating something or solving a problem, after a while, ask each group to send an envoy to another group. They could compare ideas or solutions to the problem and then report back to their own group. In this way, groups can learn from each other.

At the end of the task, summarise what has been learnt and correct any misunderstandings that you have seen. You may want to hear feedback from each group, or ask just one or two groups who you think have some good ideas. Keep students’ reporting brief and encourage them to offer feedback on work from other groups by identifying what has been done well, what was interesting and what might be developed further.

Even if you want to adopt groupwork in your classroom, you may at times find it difficult to organise because some students:

- are resistant to active learning and do not engage

- are dominant

- do not participate due to poor interpersonal skills or lack of confidence.

To become effective at managing groupwork it is important to reflect on all the above points, in addition to considering how far the learning outcomes were met and how well your students responded (did they all benefit?). Consider and carefully plan any adjustments you might make to the group task, resources, timings or composition of the groups.

Research suggests that learning in groups need not be used all the time to have positive effects on student achievement, so you should not feel obliged to use it in every lesson. You might want to consider using groupwork as a supplemental technique, for example as a break between a topic change or a jump-start for class discussion. It can also be used as an ice-breaker or to introduce experiential learning activities and problem solving exercises into the classroom, or to review topics.

Resource 2: Topics from the Class IX and Class X textbook that could be used for a group discussion

Improvement in food resources

Ask each group to think of all the ways in which we can improve crop yields. You could give them this question in advance for homework and, if you live in a rural community, ask them to talk to their relatives and friends in order to find out what people do to improve the crop yield on their land. If you live in a city, encourage the students to call any relatives they have who live in rural areas, or to go to the market and ask the people selling produce what they do to improve the crop yield.

Issues they could discuss include the following:

- Should we use chemical fertilisers on the soil? What problems can fertilisers cause?

- Pesticides are essential for growing healthy crops. The fact that they can harm wildlife is unfortunate, but not important.

- Given that there is unemployment and malnutrition in India, should our priority be to build houses and factories or to grow more crops?

Managing the garbage we produce

Conduct a brainstorm of all the sources of garbage we produce. This might include things from the home, sewage, factory waste, litter, etc. Write all the ideas on the blackboard. If possible collect some pictures that you could pass round to generate ideas.

Divide your students into groups and ask each group to come up with three ways to reduce the amount of garbage we produce as a society. If they have more than three suggestions, ask them to try and agree the three best ones. They might come up with things like:

- building a recycling plant so people are encouraged to recycle rather than just throw things away

- making plastic bags and cups much more expensive than paper ones

- making investment in sewage systems a priority

- increasing taxes to pay for garbage collectors to work in the cities.

Then ask each group to give their three suggestions. Finally, your students could vote on the one suggestion that they think would make the greatest difference to society as a whole.

Sources of energy

This will take two lessons.

Split your students into groups of five, ten or 15. Give each group one method of generating electricity to research one of the following:

- burning coal

- solar energy

- wind power

- nuclear power

- biomass.

Give them one lesson to research this method for generating electricity. They should make notes on:

- how the method works

- the advantages of this method

- the disadvantages of this method.

There will be some information in their textbook. You could also get some more books from the library or give them hints on searching the internet, and encourage them to look in books they might have at home.

In the next lesson, pose the problem that a new power station is to be built in your community. Which type should it be?

Divide your students into groups of five – but this time, make sure that each group contains one ‘expert’ on each method of generating electricity.

Ask each group to decide on which sort of power station to build in your community.

Additional resources

- Environmental Education covers the latest syllabus for the National Council of Educational Research and Training (NCERT). This has also been adopted by the Council for the Indian School Certificate Examinations (CISCE) for the compulsory subject, environmental education, from the academic year 2005–06. Details are available from: http://www.oup.co.in/ series/ school-education/ environment/ 367/ environmental-education/ 17/ level/ secondary (accessed 20 May 2014)

- A project book for Class X environmental education: http://ncert.nic.in/ book_publishing/ environ_edu/ 10/ content.pdf (accessed 20 May 2014)

- Beeta Environmental Education Class 10: https://sapnaonline.com/ beeta-environmental-education-class-10-icse-129084

- Natural resources for Class X: http://www.excellup.com/ classten/ naturalresourceten.aspx (accessed 20 May 2014)

References

Acknowledgements

This content is made available under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike licence (http://creativecommons.org/ licenses/ by-sa/ 3.0/), unless identified otherwise. The licence excludes the use of the TESS-India, OU and UKAID logos, which may only be used unadapted within the TESS-India project.

Every effort has been made to contact copyright owners. If any have been inadvertently overlooked the publishers will be pleased to make the necessary arrangements at the first opportunity.

Video (including video stills): thanks are extended to the teacher educators, headteachers, teachers and students across India who worked with The Open University in the productions.