Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Tuesday, 10 March 2026, 12:23 AM

Adolescent and Youth Reproductive Health Module: 12. Promoting Adolescent and Youth Reproductive Health

Study Session 12 Promoting Adolescent and Youth Reproductive Health

Introduction

Successful implementation of adolescent and youth reproductive health services and programmes requires the full support of young people, parents, community leaders and other influential community members in your kebele. To get the support of the community including young people, you need to promote adolescent and youth reproductive health (AYRH) using a variety of promotion methods. The same health promotion principles that you learned in the Health Education, Advocacy and Community Mobilisation and other Modules apply in promoting adolescent and youth reproductive health. In this session you will learn the best methods to use to promote adolescent and youth reproductive health.

Learning Outcomes for Study Session 12

When you have studied this session, you should be able to:

12.1 Define and use correctly all of the key words printed in bold. (SAQ 12.1)

12.2 Explain the importance of promoting adolescent and youth reproductive health. (SAQ 12.1)

12.3 Describe the different methods of promoting adolescent and youth reproductive health including community conversation, youth clubs/group discussion, peer education and age appropriate family life education. (SAQ 12.2)

12.4 Identify the health promotion strategies and actions appropriate for different age groups of young people. (SAQ 12.2)

12.1 Promoting adolescent and youth reproductive health

In Study Sessions 1 and 2 you learned that young people are especially at risk of multiple health and social problems, mainly arising from their risky behaviours. Young people can be influenced to have positive healthy behaviour provided they get sufficient support from their families, health workers and communities. Studies conducted in the years 2005 to 2006 showed that only 15% of young people living in rural areas were enrolled in secondary school and that youth reproductive health programmes in Ethiopia tend to only reach older, unmarried, urban boys who are in school. So the most vulnerable members of the population, namely rural youth (86 %), married girls and out-of-school adolescents were missed by these programme efforts. So in this Module emphasis will be given to the importance of targeting vulnerable groups of young people to get the best results from your limited resources.

Health Promotion is the process of enabling people to increase control over and to improve their health, which includes sexual and reproductive health. Young people need interventions to decrease and to alleviate their vulnerability. These include information and skills, a safe and supportive environment and appropriate and accessible health and counselling services.

Health promotion could be conducted in various settings such as schools and in the community and at health posts. In all situations, it is important to keep in mind that different groups of young people need different approaches and messages depending on their age, living and family arrangements, and school status. In the following paragraphs you will understand the specific issues that you need to address, separately, for young people aged 10–14, 15–19 and 20–24 years, orphans and other vulnerable children.

12.2 Health promotion in schools

An effective school health programme is one of the strategic means used to address important health risks among young people and to engage the education sector in efforts to change the educational, social and economic conditions that put adolescents at risk.

As the number of young adolescents being enrolled in schools is increasing all the time, school-based sexual and reproductive health (SRH) education is becoming one of the most important ways to help adolescents recognise and prevent risks and improve their reproductive health (Figure 12.1).

Studies show that school-based reproductive health education is linked with better health and reproductive health outcomes, including delayed sexual initiation, a lower frequency of sexual intercourse, fewer sexual partners and increased contraceptive use. Many programmes have had positive effects on the factors that determine risky sexual behaviours, by increasing awareness of risk and knowledge about STIs and pregnancy, values and attitudes toward sexual topics, self-efficacy (negotiating condom use or refusing unwanted sex) and intentions to abstain or restrict the number of sexual partners (Figure 12.2).

Box 12.1 elaborates the main objectives of skills-based education in schools.

Box 12.1 Objectives of skills-based health education in schools

- Prevent/reduce the number of unwanted, high-risk pregnancies

- Prevent/reduce risky behaviours and improve knowledge, attitudes and skills for prevention of STIs including HIV

- Prevent sexual harassment, gender-based violence and aggressive behaviour

- Reduce drop-out rates in girls’ education due to pregnancy

- Promote girls’ right to education.

12.3 Peer education programme

Peer education is the process whereby well-trained and motivated young people undertake informal or organised educational activities with their peers (those similar to themselves in age, background, or interests). A peer is a person who belongs to the same social group as another person or group. The social group may be based on age, sex, occupation, socio-economic or health status, and other factors.

Peer education is an effective way of learning different skills to improve young people’s reproductive and sexual health outcomes by providing knowledge, skills, and beliefs required to lead healthy lives. Peer education works as long as it is participatory and involves young people in discussions and activities to educate and share information and experiences with each other. (Figure 12.3) It creates a relaxed environment for young people to ask questions on taboo subjects without the fear of being judged and/or teased.

What is a taboo subject?

Taboo refers to strong social prohibition (or ban) relating to human activity or social custom based on moral judgement and religious beliefs. In most of our communities openly talking about sex is considered unacceptable.

The major goal of peer education is to equip young people with basic but comprehensive sexual and reproductive health information and skills vital to engage in healthy behaviours.

Several areas of adolescent and youth reproductive health such as STIs (including HIV and its progress to full-blown AIDS), life skills, gender, vulnerabilities and peer counselling could be addressed in peer education. Although peer education is mainly aimed at achieving change at the individual level by attempting to modify the young person’s knowledge, attitudes, beliefs or behaviours, it can also effect change at a group or social level by modifying existing norms and stimulating collective action.

Box 12.2 Advantages of peer education for young people

- Peer education helps the young person to obtain clear information about sensitive issues such as sexual behaviour, reproductive health, STIs including HIV

- It breaks cultural norms and taboos

- It is combined with training that is user friendly and offers opportunities to discuss concerns between equals in a relaxed environment

- Peer education training is participatory and rich in activities that are entertaining while providing reliable information

- Training in peer education offers the opportunity to ask any questions on taboo subjects and discuss them without fear of being judged and labelled

- Peer education as a youth-adult partnership: peer education, when done well, is an excellent example of a youth-adult partnership. Increased youth participation can help lead to outcomes such as improved knowledge, attitudes, skills and behaviours.

Peer education can take place in small groups or through individual contact and in a variety of settings: schools, clubs, churches, mosques, workplaces, street settings, shelters, or wherever young people gather. You will know from your own experience that young people get a great deal of information from their peers on issues that are especially sensitive or culturally taboo. Often this information is inaccurate and can have a negative effect. Peer education makes use of peer influence in a positive way.

As a health worker closely working with the community, you might be asked to give training on peer education to young people. However, before you are asked to train peer educators, you are likely to receive short-term training on how to train young people to be effective peer educators. Therefore, in this study session you will study only some basic tips that will help you in training adolescents to be peer educators. Firstly, young people, like adults, have a tendency to mask how much they don’t know about a subject. Hence, you should not assume the topic is understood because there are no questions; ask questions of the participants when they do not offer their own. Secondly, young people and adults learn better if they are neither criticised nor judged by the facilitator. It is important to keep a positive attitude. Young people will learn better in an atmosphere of support, trust and understanding.

These basic tips will also be useful to the young people who you have trained to be peer educators. They will also want to know whether they should organise some activities or just be available to talk to peers, e.g. at school, work or in a bar.

After taking the training, a good peer educator should have the following qualities.

- Ability to help young people identify their concerns and seek solutions through mutual sharing of information and experience.

- Ability to inspire young people to adopt health seeking behaviours by sharing common experiences, weaknesses, and strengths.

- Become a role model; a peer educator should demonstrate behaviours that promote risk reduction within the community in addition to informing about risk reduction practices.

- Understand and relate to the emotions, feelings, thoughts and “language” of young people.

Examples of youth peer education activities include organised sessions with students in a secondary school, where peer educators might use interactive techniques such as role plays or stories, and a theatre play in a youth club, followed by group discussions. Theatre play in this sense doesn’t mean that peer educators should be properly trained artists. It only refers to short dramas which are based on real-life experiences that young people are likely to face in their day-to-day life. Peer educators are also expected to use informal conversations with friends, where they might talk about different types of behaviour that could put their health at risk and where they can find more information and practical help.

12.4 Family life education

Family life education is defined by the International Planned Parenthood Federation (IPPF) as ‘an educational process designed to assist young people in their physical, emotional and moral development as they prepare for adulthood, marriage, parenthood, and ageing, as well as their social relationships in the socio-cultural context of the family and society’. An effective family life education helps young people to finish their education and reach adulthood without early pregnancy by delaying initiation of sexual activity until they are physically, socially and emotionally mature and know how to avoid risking infection by HIV and other STIs.

Educating adolescents in schools can lay the groundwork for a lifetime of healthy habits; since it is often more difficult to change established habits than it is to create good habits initially.

Important family life education content includes understanding oneself and others; building self-esteem; forming, maintaining, and ending relationships; taking responsibility for one's actions; understanding family roles and responsibilities; and improving communication skills.

Note from the above descriptions that family life education has many things in common with life skills (see Study Session 2 of this Module).

Traditionally adolescents get very limited information on reproductive health topics such as physiology, reproduction cycle, and life skills. Currently in Ethiopia, Family Life Education (FLE) is being taught to adolescents in primary school (from grade 7 onwards) integrated in the natural and social sciences, with reproductive health issues mainly incorporated in biology.

12.5 Community Conversation

Community conversation is a process whereby members of the different communities come together, hold discussions on their concerns and by using their own values and capacity reach shared resolutions for change and then implement them (Figure 12.4).

As you learned in the Study Sessions on HIV/AIDS in the Communicable Diseases Module and in the Health Education, Advocacy and Community Mobilisation Modules, the day-to-day activities of community conversation are handled by you working closely with the kebele health committee. It is important to use the opportunity of meeting the community in the quarterly meetings for HIV/AIDS and other diseases so that you can raise the community’s awareness about adolescent and youth reproductive health issues.

In the following sections you will learn the specific health promotion activities that you need to undertake for young people of different age groups.

12.6 Girls and boys aged 10–14 years living with their parents

Young people in early adolescence (aged 10–14 years) who live with their parents are often forced into early marriage, and suffer its consequences including early pregnancy leading to child birth complications such as fistula. They could also suffer sexual violence including female genital mutilation (FGM), abduction, polygamy and rape which predisposes them to STIs/HIV/AIDS. Because of lack of economic resources and unequal power relations with spouses girls are often unable to negotiate condom use with older spouses.

The fact that they have poor health seeking behaviour with limited access to antenatal or postnatal care and skilled delivery contributes to the high maternal mortality in this age group.

Boys are particularly at risk of dropping out of school to work. Those who migrate to urban areas are likely to live on the street.

Box 12.3 shows the main activities that you are expected to undertake on behalf of young people in early adolescence (aged10–14 years).

Box 12.3 Key actions for young people aged 10–14 years who are living their parents

- Sensitise community leaders, religious leaders, kebele officials and parliamentarians on SRH so that they will advocate on behalf of 10–14 year olds having access to appropriate information and services

- Select and train mentors and educators from the community

- Train peer educators from this age group (equal number of boys and girls) on SRH to disseminate advice on SRH and provide non-prescriptive contraceptives in clubs and other venues

- Provide age appropriate family life education in clubs and other venues where this group gather

- Awareness creation/sensitisation on the new family law which sets the minimum age of marriage at 18 years for both males and females

- Monitor and follow up implementation of SRH at the community level

- Provide training on gender and its effects on the reproductive health of young people

- Provide technical and material support to parent and teachers associations (PTAs).

- Provide technical and material support to create “safe spaces” for child brides

- Provide SRH training and family life education, negotiation and assertiveness skills for girls aged 10–14 years who are about to be married or who have already married

- Provide trained community volunteers to seek out child brides and persuade them to come to health facilities for antenatal, postnatal and delivery care.

You can use the following strategies to accomplish the activities indicated in Box 12.3:

- Create parent-teacher associations (PTAs) in schools and within the kebele committee as advocates and to follow up on enrollment and retention rates of female and male students.

- Advocate against early marriage, gender based violence and other HTPs.

- Create safe places (church, mosque, kebele) where groups meet, support each other, exchange information and receive sexual and reproductive health information and services.

- Promote antenatal, postnatal and skilled delivery services to this age group.

- Encourage and provide incentives to bring married girls and boys who have dropped out of school back to school.

- Encourage making schools gender sensitive (i.e. separate toilets for girls and boys, reduce harassment of girls on the road to schools).

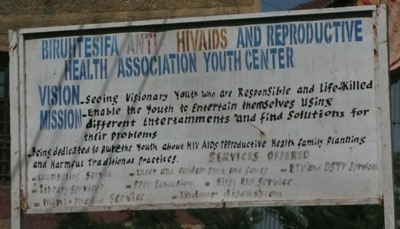

- Organise Reproductive health/HIV/AIDS clubs in-school and out-of-school. (Figure 12.5)

12.7 Girls and boys aged 15–19 years

Many in this group will be married or in a sexual relationship (remember average age at first marriage is 16 years for Ethiopian women even though marriage under 18 years is illegal). The reproductive health risks that girls in this age range are likely to encounter include sexual harassment, rape, abduction, FGM and polygamy. They are also at risk of dropping out of school because of poor performance due to work load and lack of support.

This group of late adolescents are more likely than the early adolescents to be married and to experience unwanted pregnancy, unsafe abortion, STI/HIV/AIDS. They may migrate to urban areas hoping for a better life but ending up as prostitutes (girls) and/or living on the streets (mostly boys but also girls).

What are key actions that you should undertake for this 15–19 years age group?

The key actions used for adolescents aged 10–14 years also apply to this group (see Box 12.3). In addition you need to provide youth friendly services that these adolescents can access for themselves at community level and at your health post (Figure 12.6). It may also be necessary to provide parents with communication skills and to sensitise them on the sexual and reproductive health of adolescents.

You should continue to advocate for the minimisation and eradication of sexual violence and harmful traditional practices using community conversations and dialogues; create referral linkages between schools and health facilities and outreach services, organise youth (in school and out of school) RH/HIV/AIDS clubs, gender clubs, and provide contraceptives in places where young people gather.

12.8 Young people aged 20–24 years

Important reproductive health concerns among these young people include; gender based violence, (rape, abduction), unwanted pregnancy, abortion, and sex in exchange for money or gifts. Because of this they are at risk of STIs including HIV, and of developing AIDS. Unemployment is also another significant issue that worries young people in this age group.

The key actions outlined in Box 12.3 also apply to this group. Particularly, you need to focus on training peer educators and sensitising community members to the needs for SRH services to young people whether they are married or not.

In general most strategies listed above apply to all age groups; the following are issues where you need to give greater emphasis for this older age group:

- Provide youth friendly services in vocational training schools and workplaces, and where these group congregate, ensuring you can provide an adequate supply of contraceptives

- Peer education on SRH

- Strengthen referral networks among health providers and young people.

12.9 Orphans and other vulnerable adolescents aged 10–19 years

Which groups of young people are especially vulnerable to having reproductive health problems?

As you have learned in Study Session 1, orphans, young married girls in rural areas, and youths who are abused, trafficked, physically or mentally impaired or migrate to urban areas are most vulnerable to negative reproductive health outcomes. More often they lack parental support and the financial resources to sustain on the streets and to acquiring STIs including HIV which eventually causes the themselves which predisposes them to engaging in prostitution (Figure 12.7), living development of AIDS.

It is important to keep in mind that the key actions listed above apply to these groups as well. Most of the strategies to implement the activities are also similar. Of particular importance is the need to create a safe place where they can meet to support each other and obtain RH information and services. You need to select and train individuals from the group to serve as peer educators and train community volunteers to seek out and provide them with information and services, and create a network of referrals.

Summary of the Study Session 12

In Study Session 12, you have learned that:

- Adolescent and youth reproductive health promotion needs to receive proper attention in order to protect young people from adopting risky behaviours that could negatively affect their health.

- There are a variety of ways to conduct health promotion for adolescents including school education, peer education, community conversation, and family life education. You can do promotion activities in schools, the community and at your health post.

- The kind of health promotion messages appropriate for adolescents depend on their age, living arrangements and whether they are in school or out-of school.

- Peer education is one of the effective strategies used to improve young people’s reproductive and sexual health outcomes by providing the knowledge, skills and beliefs necessary to lead healthy lives.

- Adolescent family life education is an effective adolescent health promotion strategy. It provides knowledge on physical, mental, social, moral, behavioural and mood changes and developments during puberty.

- Community conversation is also one the key strategies that should be used to raise the community’s awareness and to bring about positive behaviours among adolescents and young people.

- Young adolescents (10–14) who live with their parents may have reproductive health problems such as early marriage and pregnancy leading to difficult child birth with later complications such as obstetric fistula. They may also experience sexual violence (including FGM, abduction, polygamy and rape).

- Adolescents in the age group 15–19 years face similar reproductive health risks such as sexual harassment, rape, abduction, FGM and polygamy. They are more likely to be married but if they have unwanted pregnancies they may resort to unsafe abortion. They are also more likely to acquire STIs such as HIV and to develop AIDS.

- Major issues among young people aged 20–24 years include; unemployment, gender-based violence, (rape, abduction), unwanted pregnancy/abortion, and sex in exchange for money or gifts. Because of this they have the greatest risk of STIs including HIV/AIDS.

- To effect positive behaviour change, you need to be active in training or sensitising community leaders, religious leaders, kebele officials, and parliamentarians on SRH so that they too can advocate on access to information and services.

Self-Assessment Questions (SAQs) for Study Session 12

Now that you have completed this study session, you can assess how well you have achieved its Learning Outcomes by answering these questions. Write your answers in your Study Diary and discuss them with your Distance Learning Tutor at the next Study Support Meeting. You can check your answers with the Notes on the Self-Assessment Questions at the end of this Module.

SAQ 12.1 (tests Learning Outcomes 12.1 and 12.2)

In the rural village where you are working you are informed by the kebele leaders that the adolescents are having significant problems. Some identified problems are violence against adolescent girls on their way to school or to social activities such as markets, and fetching water, boys engaging in risky behaviours including drinking alcohol, chewing khat, and going to prostitutes especially when they get the chance to go to the towns. There are two primary and one secondary school serving the neighbouring communities.

- a.What strategies would you use to approach the adolescents?

- b.Which groups of individuals in the community need to be involved to implement your activities aimed at changing the behaviour of the adolescents?

Answer

- a.There are many ways you can reach the adolescents. You may organise community conversations (in schools or in the community) to increase the community’s awareness of protective behaviours. You may also use peer educators to promote age appropriate family life education.

- b.To effect positive behaviour change, you need to be active in training or sensitising community leaders, religious leaders, kebele officials, and parliamentarians on adolescent and youth sexual and reproductive health issues so that they too can advocate on access to information and services for young people.

SAQ 12.2 (tests Learning Outcomes 112.1, 2.3 and 12.4)

In the same village where you are working (SAQ 12.1), you note that the adolescents aged 15–19 are a particularly vulnerable group who need your special attention.

- a.What are the common challenges that you expect adolescent girls aged 15–19 years to experience?

- b.What specific actions are necessary to address your concerns for this group?

Answer

- a.In a rural setting these groups of girls are considered mature enough to get married and hence start sexual activity. They may nevertheless have unwanted pregnancies and this may lead them to seek unsafe abortions. Some may be in polygamous marriages or married to an older husband and they may not have been able to negotiate for safer sex using a condom thereby possibly exposing themselves to the risk of STIs such as HIV. They may also have to face other reproductive health risks including; sexual harassment, rape, abduction and FGM They are at risk of dropping out of school because they are expected to do other work.

- b.These are some of the activities that you are able to initiate:

- Select and train mentors and educators from the community.

- Train boys and girls as peer educators on SRH to disseminate information and provide non-prescriptive contraceptives in clubs and other venues where young people in this age group gather.

- Provide age appropriate family life education in clubs and other venues where this group gather.

- Create awareness of the new family law which sets the minimum age at marriage of 18 years for both males and females.

- Train and sensitise parents, community members and faith based organisations on SRH issues such as HTP, gender based violence.