Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Wednesday, 11 March 2026, 8:04 AM

Developing and managing relationships

Introduction

In this section of the course you will be looking at the development of children’s relationships, both within the family and in schools. It is not intended to be a comprehensive account of how children grow and develop. What it aims to consider are some of the experiences and challenges faced by children and their parents/carers in society today and introduces you to important theories of how children develop and mature.

This section is divided into three topics:

The importance of the early years looks at what babies and toddlers get from having a range of relationships and why securing early relationships is important to babies and young children.

Parents as partners explores the development of relationships with reference to some of the main theorists who have shaped our understanding. You will also focus on how the nature of parenting can affect children’s development, and the importance of the relationships between parents and practitioners.

Children’s transitions focuses on the importance of understanding significant changes in the lives of children as they move from one stage of development to another. ‘Transition’ literally means ‘passing from one place, condition, form, stage or activity, to another’ (YourDictionary, nd).

We all experience different sorts of transitions on a daily basis and throughout our lives. A horizontal transition involves literally a move from one place to another, such as from home to school. A vertical transition involves a change of experience such as ‘moving up’ from nursery to primary school, or from primary to secondary. Education-associated transitions are less obvious and refer to the less formal changes in children’s lives and routines that occur outside an institutional setting. These changes may occur in everyday life away from school but can affect and shape children’s lives and well-being. Divorce would be an example of this sort of change.

Learning outcomes

By completing this section and the associated quiz, you will:

gain an insight into the importance of attachment of secure relationships in the development of children from the early years

understand how some theories and concepts attempt to explain how relationships develop in childhood and how an understanding of theory and concepts can contribute to your practice.

1 The importance of the early years

You are going to start by exploring relationships in the early years through the lens of a case study family. The account pinpoints a number of possible factors impacting on the children’s relationships. Make a mental note of these factors as you read the case study, but note that you may have other views due to your different interests, prior knowledge and experiences.

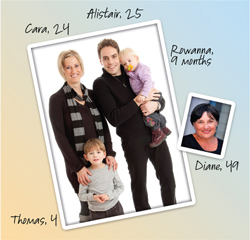

Case study: Forming early relationships

Thomas (4) and Rowanna (9 months) live with their parents, Cara and Alistair, a young married couple in their twenties, and their grandmother, Diane. Diane is Alistair’s mother. Cara and Alistair have known each other since they were at school together and married when Cara found out she was expecting Thomas. Although Diane tries hard not to interfere with how Cara and Alistair bring up their family there are inevitable tensions with the three adults sharing a house and Thomas, at four, is beginning to play his parents and grandparent off against each other.

Cara has decided to go back to work full time now that Thomas is moving on from preschool into mainstream schooling. Rowanna has been a very clingy baby and Cara is worried about how she will cope with being away from ‘Mummy’ and going into day care.

Thomas was a very easy baby – very placid and quiet. As a toddler he often seemed to be in his own world and did not interact with other children. Thomas’s parents put his behaviour down to having a reserved personality, and were secretly very pleased with their well-behaved little boy. During a routine health check Thomas was diagnosed as having a hearing impairment and over the past year has undergone various medical tests. He now sees a speech and language therapist on a regular basis.

Rowanna has been a more difficult and demanding baby, suffering from colic until she was 4 months old. Cara had difficulty bonding with her and wonders if there will be any long-term effects on her relationship with her daughter, or on Rowanna’s social and emotional development.

As a baby, Thomas was happy to lie quietly in his cot, or amuse himself as he got older, and did not seem to want lots of attention. As a result, Cara was able to work part time. Between them, Cara, Diane and Alistair were able to care for Thomas without him going into day care until he started preschool at the age of 3. Juggling work and family time, however, meant taking Thomas out to meet other babies and toddlers was not easy. When Cara and Alistair went to a parents’ meeting with the preschool to discuss his transition to school, they were not surprised to hear that he has no special friend, and that he is quite happy playing on his own.

As Thomas has a hearing impairment he was referred to a speech and language therapist. This was a great shock to his parents and they found it hard to adjust. However, they were determined to do all they could to help him. They spend a lot of time carrying out exercises and activities suggested by the professionals they see. Thomas does not always want to do these, and Cara and Alistair sometimes resort to cajoling and bribing him to do what they want. Thomas gets upset and, on occasions, Diane steps in and lets Thomas have what he wants without doing what he has been asked to do. This has caused some friction between the adults in the house for a time.

When Rowanna was born a few months after Thomas’s diagnosis, Cara, particularly, found it very difficult to cope with the differing demands of the two children. Rowanna has been the total opposite to Thomas as a baby. She suffered from colic and cried a lot, and woke frequently in the early months. Alistair worked a lot of night shifts so that he could be about during the day to take Thomas to preschool and give Cara a break, but this left them both tired and exhausted. Although Diane had tried to keep in the background when Thomas was a baby to allow Cara and Alistair the freedom to develop their own parenting skills, she has become much more involved with baby Rowanna.

From a very tiny baby Rowanna hated being put down and would scream or cry unless she was being cuddled or sleeping. Her clingy behaviour was very wearing on the family. Diane, who did a lot of the early caring, spent many hours cradling Rowanna in an attempt to calm her, while Cara was busy with Thomas. Rowanna now has a very close bond with her ‘Nanna’. She loves to cuddle up to Diane for a story and will often choose to go to her when she is hurt. On a recent occasion, when she fell over playing in the garden, even though Cara was nearer to her, Rowanna chose to go to her grandmother for comfort rather than her mum. Cara found this small incident upsetting and it has made her realise that she needs to spend more time with Rowanna and work to build up their relationship.

Rowanna’s relationship with Cara appears to be less secure than her relationship with Diane. While she seems happy enough to be with Cara there are little hints that she feels more sure of her relationship with Diane, such as settling more easily for Diane when she is upset . Cara is grateful to Diane for helping with Rowanna, but has begun to worry that she takes second place to Nanna in her daughter’s eyes. Thomas found it hard to adjust to sharing his parents with Rowanna when she was first born but he loves his little sister now, and likes to play with her, although he can get annoyed with her, too – particularly when Rowanna tries to grab his favourite dinosaur model!

Activity 1

Reread the case study and make a note of:

- What factors may have impacted on both Thomas and Rowanna’s relationships with their parents and grandmother?

- What possible reasons are there for why Rowanna may not have formed a close relationship with her mother?

Comment

The account highlights some possible factors that may affect the children’s relationships. Below are some of the factors you may have identified, but you may have noted different ones. Your answers may reflect your different experiences, interests and prior knowledge.

Thomas’s diagnosis of a hearing impairment came while Cara was expecting Rowanna. Cara had to spend a lot of time taking Thomas to appointments and carrying out activities with him to help him with his language development. This naturally will have impacted on Thomas’s relationship with his parents and grandmother as everyone coped with the demands an early intervention approach placed on the family.

Thomas’s behaviour and subsequent diagnosis, and the busy lives of his parents, may have affected how easy he found it to form relationships with other children, although he appears to be forming a healthy sibling relationship with his sister.

Rowanna has a very close, secure, relationship with her Nanna as she did a lot of the early caring while Cara was busy with Thomas. Cara found it difficult to bond with Rowanna when she was born, possibly because her focus was on Thomas but also because Rowanna was a ‘difficult’ baby. There is a hint that Rowanna may not be sure that her mother loves her and may have a less secure relationship with her, evidenced by Rowanna going to her Nanna when she was hurt.

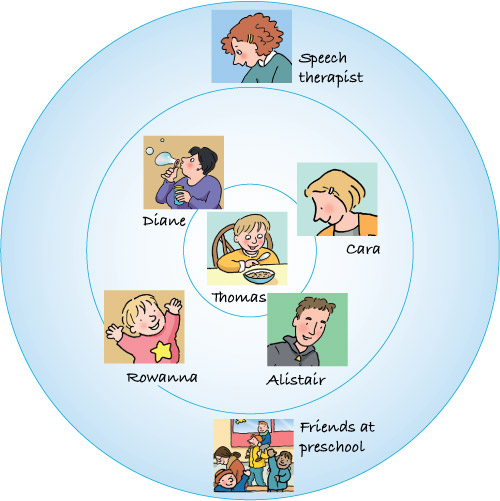

1.1 Important relationships

Figure 3 shows one way of representing the range of different people that Thomas comes into contact with on a regular basis and how close they feel to him. Do you notice anything about the range of people mentioned? In this case study (but not in all families) family members are the closest. After that key workers in schools such as speech therapists might be the closest. As children develop, peers become of increasing importance.

Activity 2

Think back to your early childhood and try to remember whom you were close to when you were Thomas’s and Rowanna’s ages. Have a look at photographs from your early childhood or talk to relatives. If you prefer, carry out this activity from the perspective of your own children, or children you know well.

Produce a diagram similar to Figure 3 to provide a visual representation of the information or jot down some notes about the following, giving reasons for your answers if you can:

Who were you close to?

Are you still close to them now?

Comment

You may have been surprised by the range of people you identified as feeling close to, and forming a strong bond with. Maybe you identified aunts and uncles, grandparents, a step-parent, a foster carer or a non-relative who cared for you, such as a babysitter or a family friend.

For most young children, parents and immediate family are important. Other adults and children can be, too, but do not always get the credit they deserve for their parts in children’s lives.

1.2 Some child development theories

Some people find theory a bit heavy going, although it is important in understanding child development. You do not have to spend long on the theory at this stage of your studies. The external links are optional and not included in the study time for this section.

Rowanna was less attached to Cara, her mother, than Cara would have liked because of Rowanna’s close attachment to her grandmother. Attachments are emotional bonds made between a young child and the people most involved with them. The reliability and consistency of care a baby receives appropriate to their needs impacts on how secure they feel in their attachments; if they feel secure, a firm bond is likely to be established with the person giving that care. However, inconsistency and unpredictability in a relationship can make a child feel very insecure, and this will have a negative impact on how well a bond is formed.

By 6 to 12 months a baby is capable of making a firm emotional relationship (attachment) with others and once an attachment is formed the baby becomes wary of strangers and upset if separated from the person(s) they are attached to.

Attachment theory and the Strange Situation Test

The Strange Situation Test has been used by child psychologists in Western Europe and the USA for many years to assess the quality of attachment relationships in young children. This has usually been done with mothers as the main carers.

Activity 3

Watch this video clip of the Strange Situation Test being carried out on baby Lisa by a psychologist. The video clip shows that baby Lisa is securely attached to her mother.

Transcript

The Strange Situation – Mary Ainsworth

Comment

The Strange Situation Test has been criticised on several counts – for example, it cannot be easily repeated. The research has been mainly carried out on Western European and American children, so interpretations of what secure relationships should be like are very specific to European–American cultures.

There are societies and ethnic/cultural groups where babies are not encouraged to explore, play away from family or show curiosity, so would not behave in this way when young (Cole, 1998). In assessments of the security of their relationships, therefore, these babies may be wrongly assessed as being not secure.

Attachment theory

A psychologist called Mary Ainsworth (1913–1999) devised the Strange Situation Test but the test is closely linked to the theory of attachment. Attachment theory has become very well known in psychology and is closely associated with the work of John Bowlby (1907–1990), who carried out work on attachment in the 1940s and 50s.

Recent research has shown that not only can babies form multiple attachments but that they are often better able to form relationships in the future if they form more than one primary attachment (David, 2004). These primary attachments do not have to be with the child’s parents. Sometimes children form a primary attachment with a close relative, such as a grandparent, or a parent figure, such as a long-term foster carer. Remember in the case study family that baby Rowanna was closer to her grandmother Diane who looked after her while her mother Cara was working.

Developmental theory

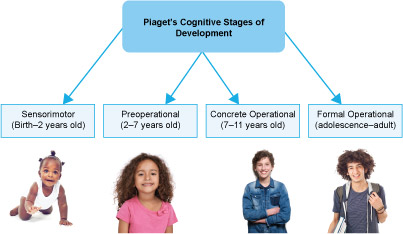

How children learn and develop is a huge area of developmental psychology and there are differing views underlying the experiences children are exposed to. Two theorists in particular have been influential in child development. They are Jean Piaget (1896–1980) and Lev Vygotsky (1896–1934).

Piaget’s theory argued that development occurred mainly through factors internal to the child that are biologically generated and that all children go through stages of development at roughly the same time. Don’t worry too much about the four different stages (although you may want to have a go at Question 1 of the quiz at this point).These stages (Figure 5) are:

- Sensorimotor (0–2 years)

- Preoperational (2–7 years)

- Concrete operational (7–11 years)

- Formal operational (11–15 years)

These are complex stages of cognitive development and if you choose to study child development in more depth, you will learn more about them. The following is a summary of the main features of each stage of development. Piaget argued that all children follow these stages sequentially.

Stage 1: Sensorimotor (0–2 years). The child learns by doing and this includes looking, touching and sucking. They have a basic understanding of cause-and-effect relationships. Object permanence appears around 9 months.

Stage 2: Preoperational (2–7 years). The child uses language and symbols, including letters and number. Egocentrism is evident. Conservation marks the end of the preoperational stage and the beginning of concrete operations.

Stage 3: Concrete operational (7–11 years). The child can demonstrate conservation, serial ordering and a more mature understanding of cause-and-effect relationships.

Stage 4: Formal operational (adolescence–adult). The individual can demonstrate abstract thinking including logic, deductive reasoning, comparison and classification.

In contrast to Piaget’s biologically based stages of development, the Russian, Lev Vygotsky, considered environmental factors, such as the child’s social development, to be more important in stimulating and supporting development. This is known as the theory of social constructivism or socio-cultural theory.

Alistair and Cara have become aware through Cara’s studies that Vygotsky’s theory is behind what they are doing when they work at home with Thomas on the exercises set by the speech and language therapist.

To give one example, Thomas can make the sounds ‘sss’ and ‘shh’ but he muddles them up, so the speech therapist has asked them to model the sounds they want Thomas to make by saying a simple tongue twister: ‘Smelly shoes and socks shock sisters’ and then encourage him to copy them.

In just a few days his pronunciation has improved and Thomas has found the activity – the learning experience – to be enjoyable, probably because he finds it funny, having a sister to shock with smelly shoes and socks.

Vygotsky, like Piaget, has argued that children learn through play. However, he emphasised the importance of engaging with other children during play. Cara and Alistair can see how much Rowanna has benefited from having Thomas there to watch and learn from.

Although they know there are other potential reasons for the differences between the two children, they have noticed that Rowanna has met the milestones of crawling and trying to feed herself, for example, much earlier than Thomas. They have also noticed Thomas trying to teach her things, such as how to stack the bricks from her brick trolley, now that she is much more in control of what she can do with her body.

2 Parents as partners

Parents play a crucial role in the development of their children and, in today’s society, there are as many different styles of parenting as there are types of family. If you are a parent, you may have thought long and hard over decisions you have made and the impact they have had on your child. Within families, your style of parenting may differ from that of your partner, or your own parents. If practitioners are to become reflective, it is important that they think about their own style of parenting or interacting with children.

When reading about Thomas and Rowanna’s early relationships in ‘The importance of the early years’ topic, you may remember that Diane, the grandmother, had a more relaxed approach towards the children. As grandparents often do, Diane took the ‘soft’ approach of ‘if you don’t feel like it you don’t need to do it’, whereas Cara and Alistair tried to establish a more disciplined approach.

Developmental psychologists have long been interested in how parenting styles impact on a child’s development. Finding actual cause–effect links between specific actions of parents and later behaviour of children is very difficult. Some children raised in dramatically different environments can later grow up to have very similar personalities. Alternatively, children who share a home and are raised in the same environment can grow up to have very different personalities. Despite these challenges, researchers have uncovered convincing links between parenting styles and the effects these styles have on children.

During the early 1960s, psychologist Diana Baumrind conducted a study on more than 100 preschool-age children. She identified four important dimensions of parenting:

disciplinary strategies

warmth and nurturance

communication styles

expectations of maturity and control.

Based on these dimensions, Baumrind suggested that the majority of parents display one of three parenting styles, as shown in Table 1.

| Parenting style | Parenting behaviour | Potential impact on child | Phrases a parent might use |

|---|---|---|---|

| Authoritarian | Strict discipline Child expected to follow rules No opportunity for child to negotiate | Discontented Withdrawn Mistrustful Rebellious (as they get older) | ‘No you can’t …’ ‘Because I say so, that’s why’ ‘Do it – NOW!’ |

| Permissive | Issue few commands and have few rules or boundaries May take time to explain their decisions to the child Leave child to regulate their own behaviour A friend rather than parent to their child | Impact can be both positive and negative Insecure Demanding and self-centred Lacking in personal responsibility Better social skills Belief in themselves | ‘It’s up to you. If that’s what you really want to do then …’ ‘The reason for wanting you to … is …’ ‘Well, if you don’t feel like it …’ |

| Authoritative | Exercise control over their child’s behaviour but also encourage them to be individuals Listen to what the child has to say Set clear standards and non-punitive punishments | High levels of self-esteem Achieve better at school Independent Socially competent | ‘This is my view … but what are your thoughts?’ ‘Sorry, but we agreed …’ |

Activity 4

Look again at Baumrind’s three parenting styles (Table 1) and then think about the parenting styles of Alistair, Cara and grandmother Diane. Which parenting style did each person use?

Comment

Grandmother Diane has a more permissive parenting style, but Alistair and Cara are authoritative rather than authoritarian. Neither parent is a strict disciplinarian, nor are they permissive – they do not allow their children to set their own boundaries or regulate their own behaviour.

In Baumrind’s four dimensions of parenting styles, most parents today would prefer to be authoritative rather than authoritarian. In the discussion of attachment theory, you have seen how important a child’s relationship with their parents is in the early years and how this can affect the future development of the child.

As a teaching assistant, or learning support worker, you need to recognise the importance of parents as partners. If you want to find out more, visit Parents as partners (an OpenLearn course). There you will discover that partnership can take many different forms. You will find that the relationship between parents and practitioners is not always straightforward and that some parents are tentative or professionals may be defensive when challenged.

Activity 5

Read Section 1.2.3 of the Parents as partners course and try to find out why working together is so important.

Comment

Working collaboratively with parents is important to children’s identity, self-esteem and psychological well-being. This alone is a compelling reason for a close partnership.

3 Children’s transitions

‘Transition’ means ‘passing from one place, condition, form, stage or activity, to another’ (YourDictionary, nd). We all experience different sorts of transition on a daily basis and throughout our lives. Vogler et al. (2008) distinguished between horizontal and vertical transitions by linking them to specific activities. Horizontal transitions occur on a daily or regular basis and usually refer to movement or a change in routine. Horizontal transitions describe activities such as children going from the classroom to the playground (a movement) or taking part in the annual sports day event (a change in routine).

In contrast, vertical transitions are much more significant and linked to specific events that do not happen on a regular basis. Starting school is described as a vertical transition and, interestingly, we often discuss children moving ‘up’ from nursery to primary school and moving ‘up’ from primary school to secondary school. The role of parents is particularly important in the vertical transitions children experience in moving ‘up’ from one school to another, but so is the role of teachers and teaching assistants (TAs).

‘Again it is often the TA that has to deal with a child’s fears about this as they have more time to be able to sit and discuss their worries with them.’

Vogler et al. (2008) discuss a third type of transition called education-associated transition. This refers to those less formal changes in children’s lives and routines that occur outside institutional settings. These changes may occur in everyday life away from school but can affect and shape children’s lives and well-being; divorce would be an example of this sort of change as the child may have to move from one parent to another. For many children today, the make-up of their family life may change several times throughout their childhood and they may experience transitions of moving between homes when visiting parents and living with stepbrothers and sisters.

The timings of vertical transitions, such as starting school at 5 and moving up to secondary school at 11, are based on child development and were particularly influenced by the work of Jean Piaget. His belief that all children, at more or less the same time, went through the four cognitive stages of development, strongly influenced concepts of when children were, for example, ‘ready for school’ and hence informed the timings of vertical transitions within the English education system.

Transitions happen to all of us throughout our lives. Some are common to most of us, such as starting school or becoming a parent. Major transitions such as these are like milestones in our lives – we pass through them and look back at them. When we look back at them we remember how we felt at the time and this can affect how we feel about ourselves and our ability to cope with new situations, such as starting a new job or becoming a member of a local community group.

3.1 From home to school

We probably all vividly remember our first day at primary school. The case study below introduces you to Laura and her memories of her first day at school.

Case study: Laura’s first day at primary school

Laura is 11. She looks back on her experiences of her first important transition from home to school. This was firstly a horizontal transition, as it involved a physical move literally from one place to another. But it was also a vertical transition, as it involved a change of experience, a moving ‘up’ into primary school.

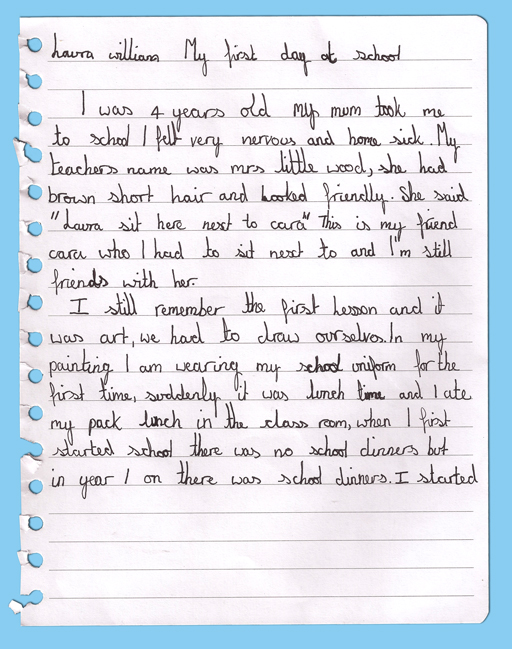

In Figure 7, Laura remembers her first day at school and the feelings she had about being left in a strange setting. Her teacher played an important role in making the transition easier for Laura. The detail with which she remembers the day shows how memorable the experience was to a young child of 4.

For young children, the vertical transition from home to school will most likely also involve a change in carer, such as from Mummy to teacher. For older children, the move from primary to secondary school will also involve changes in routine, such as having to move around the school to different classrooms for all the different subjects being studied. For many children, moving to secondary school can mean a further change in friendship groups, as often children are allocated to different schools depending on catchment areas or by parental choice.

Activity 6 asks you to identify and reflect on transitions in your early life.

Activity 6

Comment

It is most likely that you will have identified the transition of starting school or leaving school. You may have identified when you moved house or moved to a different country as a horizontal transition. Starting Cubs or Brownies, or leaving them, may have left you with strong memories of vertical transition.

3.2 From primary to secondary school

Laura’s story continues.

Case study: Laura’s transition from primary to secondary school

Now that Laura is 11, she is about to make the transition from primary to secondary school. She is excited but also a little apprehensive. Laura and her mother Christine attended the information evening held at Laura’s school. As well as teachers and teaching assistants from the primary school, the head of pastoral care and the head of year 7 from the secondary school were also there.

It became clear that teaching assistants (TAs) at the primary school were significantly involved with supporting year 6 pupils and their parents/carers during the transition. Many children have less formal relationships with their TA than with their teacher and often find it easier to approach them rather than the class teacher with a worry or a question they may have.

Laura discovered that the school recognises that the transition from primary to secondary school is a major milestone for pupils and their parents. So the school deploys TAs to work alongside teaching staff in a supportive role to ensure the correct information is given regarding the transition and also to offer pupils individual support as necessary.

Laura has a good relationship with the TA who assists in her class and was reassured by this. Christine was pleased to discover that the TAs would also offer support to parents/carers if approached but would if necessary pass on such concerns to the teacher.

Laura found out that her new secondary school will hold an informative open evening for both pupils and their parents/carers before the transition, and staff from the secondary school will come to visit pupils during the primary school day. The staff visiting would be the year 7 form teachers so Laura’s first meeting with her new form teacher would be on familiar territory. Laura felt that she would be able to ask any questions from the ‘safety’ of her own classroom with both her teacher and TA in attendance.

Pupils will also go to the secondary school for two visits during the school day and Laura’s TA will be on hand to offer help and support to any pupil but especially those who seem nervous or anxious. Primary school staff will communicate with their secondary school colleagues and with parents/carers as necessary to ensure the transition will be as smooth as possible.

Christine found it reassuring that pupils are invited to visit the secondary school for an extra day or so to help familiarise them and ease the transition – this gives the secondary school staff a little more time to get to know them and for the pupils to feel comfortable about the forthcoming changes.

3.3 The transition to secondary school

It is quite common for children to worry about the transition to secondary school. Some children undertake this transition ‘alone’ without the support of their friends or parents. Children can worry about what going to secondary school will mean. They wonder if the school work will be much harder and whether they will be able to cope with it. It is important for schools and teachers to recognise these worries and support children before and after the transition.

Many secondary schools include sports activities and social activities in the early weeks of new pupils joining and many children benefit from this. Once settled, year 7 children quite like being treated more as an adult and less like a child within the secondary school environment. Key factors for a successful transition appear to be parental/carer support, other pupils, teachers and a programme of targeted social activities.

The roles played by other adults and peers appear influential in making a successful transition. Earlier in this section you were introduced to the ideas of Lev Vygotsky who researched the significance of social interaction or support with parents or carers and went on to describe it within social constructivism or socio-cultural theory.

Social constructivism or socio-cultural theory places significant emphasis on how the culture that we live in and the people we interact with (our environment) influence how we learn, behave and adapt to new situations. Vygotsky’s view was that children actively engage with their own environment and by doing so learn how to adapt to new situations.

Vogler et al. (2008) described how ‘Transitions can be understood as key moments within the process of socio-cultural learning whereby children change their behaviour according to new insights gained through social interaction with their environment’. Of importance here is the key issue of children engaging or interacting with others. In doing so it implies a two-way process and the readiness of children to adapt to the new situation.

Preparing children for this readiness is an important role for schools as well as parents. The majority of children do go on and undertake this transitional process successfully. But what happens with very shy children, reluctant children and those for whom not only is the school new but so is the culture in which their education is taking place?

The move to secondary school means a number of changes for all children and without doubt this transition can be stressful both for children and their parents. From a child’s point of view moving from primary school can mean loss of friendship groups, finding their way round a much a larger school environment and no longer being at the top of their school.

For most children, after two to three weeks spent in their new environment, they become more settled and more confident about life within a secondary school. For some children, settling into life at secondary school can take two to three terms or longer!

So what is different about a secondary school and what difficulties may arise during the transition from primary to secondary school? Table 2 identifies some of the main differences between primary and secondary school and why some children might find this transition difficult.

| Differences between primary and secondary school | Transition difficulties between primary and secondary school |

|---|---|

| Subject-specific teachers instead of class teachers | Learning lots of teachers’ names, their expectations and styles of teaching |

| Pupils use a locker rather than having a desk | Less supervision of pupils at break time by teachers |

| Independent travel to school | Finding their way around a much larger school |

Activity 7

Having looked at Table 2, now try to think of some more differences and difficulties. You could draw on your own experience of moving to secondary school or that of your son or daughter or other relative.

Make some notes before reading our comments.

Comment

Not all children move at the same time to secondary schools. Some local authorities operate a middle school system that children attend from age 10, but the transition from primary school can be stressful for children regardless of how schools are managed within local authorities.

Children used to being thought of as the oldest in their primary school now become ‘little fish in a big pond’. Having to remember to take books to lessons and to hand in homework, perhaps to shelves near the staffroom, are all things that newly arrived secondary children have to learn to deal with. They may find themselves in classes that are ‘streamed’ or ‘set’ and therefore not always with the same group of class friends. And meeting a tall, mature sixth former who may be their class prefect means negotiating their ‘place’ in their new environment.

Most transitions pass unnoticed but some can impact greatly on the lives of both children and adults. This section has defined three types of transition and considered vertical transition in particular. It has looked at how best to support children’s transitions from home to school and between schools and identified key factors. It has located the move from primary to secondary school within a socio-cultural context by recognising the influence of parents, carers and significant others, such as teaching assistants, on children’s ability to cope with change. The transition from childhood to adulthood is one we all pass through and the teenage years can be linked to other transitions to work, college or university.

What you have learned in this section

- Some important concepts and theories in the development of children. Starting from the early years, you looked at the importance of secure attachment. In the Strange Situation Test you found that some children may not be securely attached because they have experienced disruption in their lives. The Strange Situation Test was followed by a brief introduction to John Bowlby on attachment theory.

- The views of Jean Piaget. He believed that children go through four stages of development and this is biologically based. In contrast, the Russian psychologist Lev Vygotsky developed the theory of social constructivism or socio-cultural theory, which argued that social and environmental factors were more important than biology in children’s development.

- The importance of parents as partners, as well as different styles of parenting, through the work of Diana Baumrind. Teaching assistants recognise the importance of working closely with parents and that this relationship can take different forms and be challenging as well as supportive.

- Transitions and how horizontal, vertical and education-related transitions can help us to understand the importance of these moves from one setting to another. You also looked at some of the issues faced by children experiencing these transitions.

Section 1 quiz

Well done, you have now reached the end of Section 1 of Supporting children’s development, and it is time to attempt the assessment questions. This is designed to be a fun activity to help consolidate your learning.

There are only five questions, and if you get at least four correct answers you will be able to download your badge for the ‘Developing and managing relationships’ section (plus you get more than one try!).

- I would like to try the Section 1 quiz to get my badge.

If you are studying this course using one of the alternative formats, please note that you will need to go online to take this quiz.

I’ve finished this section. What next?

You can now choose to move on to Section 2, Encouraging reading, or to one of the other sections so you can continue collecting your badges.

If you feel that you’ve now got what you need from the course and don’t wish to attempt the quiz or continue collecting your badges, please visit the Taking my learning further section. There you can reflect on what you have learned and find suggestions of further learning opportunities.

We would love to know what you thought of the course and how you plan to use what you have learned. Your feedback is anonymous and will help us to improve our offer.

- Take our Open University end-of-course survey.

References

Acknowledgements

This free course was written by Isobel Shelton and Sue McKeogh (staff tutors at The Open University). Contributions were made by Katie Harrison (teacher and member of the ATL Union).

Except for third party materials and otherwise stated (see terms and conditions), this content is made available under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 Licence.

The material acknowledged below is Proprietary and used under licence (not subject to Creative Commons Licence). Grateful acknowledgement is made to the following sources for permission to reproduce material in this free course:

Every effort has been made to contact copyright owners. If any have been inadvertently overlooked, the publishers will be pleased to make the necessary arrangements at the first opportunity.

Figures

Figure 1: © Agelika Schwarz/iStockphoto.com; © Elena Ellisseeva/iStockphoto.com

Figure 2: © The Open University

Figure 3: © The Open University

Figure 4: © unknown

Figure 5: Left to right: © PeopleImages/iStockphoto.com, Shapecharge/iStockphoto.com, ImagePhotography/iStockphoto.com, Sebra 1/iStockphoto.com

Figure 6: © The Open University

Figure 7: © The Open University

Figure 8: © The Open University

Video

Activity 3

The Strange Situation – Mary Ainsworth transcript: https://www.youtube.com/ watch?v=QTsewNrHUHU#t=16 thibs44