Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Thursday, 22 January 2026, 12:46 AM

Encouraging reading

Introduction

Encouraging reading is a general introduction to some important aspects of how children develop their literacy and reading skills. In particular, it aims to raise your awareness of some of the main issues in how children learn to read and how you as a teaching assistant can encourage children to enjoy reading and improve their literacy skills.

We all want children to enjoy reading and many of us can remember a favourite book from our own childhood. An Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) study reported by BBC News in 2011 made the bold statement that ‘Children whose parents frequently read with them in their first year of school are showing the benefit when they are 15’ (OECD, 2011). Early support means that children remain ahead in reading and that there is a strong link between the reading skills of young people and early parental help.

It is not only parents who can offer this early vital support, but also teachers, teaching assistants and the range of other learning support workers. Often, teaching assistants working in a one-to-one relationship with a child are in a much stronger position to read with them or listen to their reading.

This section consists of three topics:

- Babies and the early years

- Moving from the early years to primary

- Boys, girls and reading.

They cover the different stages of child development and some of the ways you can encourage reading and literacy in each of these stages, from the early years to young people in secondary schools

Learning outcomes

By completing this section and the associated quiz, you will:

gain an insight into the varying perspectives on reading and how it is taught, in relation to children from early years through to secondary school

develop an understanding of the ‘reading gap’ and why there is a ‘gender gap’ in reading, and consider the implications for practice.

1 Babies and the early years

To understand literacy skills, we would like you to start by thinking about how babies learn to communicate.

It is well known that babies want to communicate with other people and they move quickly from communicating through crying and making noises to saying recognisable words. The following extract taken from the Words for Life website shows how quickly babies move on from those initial communications to saying their first word, then on to speaking their first sentence.

Baby and toddler communication milestones

‘Look at me copying you.’

From birth I will make eye contact and copy your expressions. This is one of the first ways in which I learn to communicate.

‘My first smile.’

Around six weeks I may smile for the first time.

‘My first laugh.’

Between three and six months I will probably start laughing. Hearing my infectious laughter will help us bond even more and make it more rewarding to talk and interact with me.

‘Mummy look at me!’

At around six months I will start using noises to get your attention; coos or gurgles.

‘Ma ma ma, Da da da’

Around eight months I will probably start to babble. The repetitive noises I make are the beginnings of speech and give me the chance to exercise my mouth.

‘Did you say my name?’

Around eight or nine months I will begin to recognise and respond to my name.

‘My first word!’

Around 12 months I may say my first word. And by 13 months I may be using up to six words.

‘I’ve reached 50 words!’

Around 18 months I will have increased my vocabulary to about 50 words. This is a time in my life where you may notice an explosion in my vocabulary; it’s an exciting time for me as I quickly add more and more words.

‘My first sentence!’

At some point between the ages of 18 and 24 months I will put together my first sentence. It may not be grammatically correct or easy to understand but it’s a very important part of my language development. Remember to keep reading, talking and interacting with your child as this will help them continue to expand their vocabulary and their understanding of grammar, words and language.

Activity 1

Transcript

Babies’ communication

James

James Description:

Baby James is lying in a chair looking at his Mother who has eye contact with him and is talking to him and smiling. She sometimes holds his hands and James moves his head towards her and gurgles.

James smiles at his Mother and moves his body as though he is trying to reach out to her. James has lolled to one side, still maintaining eye contact with his Mother who gently moves him upright.

As his Mother talks gently to him, James smiles in response. James is aware of the happiness in his Mother’s voice by gurgling and smiling.

Alice

Alice Description:

Alice is lying on her back on a baby changing mat and is looking at her Mother who is leaning over her. Alice responds to her Mother’s voice by moving her arms and gurgling. Alice also moves her body.

Alice waves her arms in the air and is quite active. Alice is looking at her Mother at all times. When her Mother asks Alice should she answer the door as the bell has rung, Alice squeals as though in response to the question.

Alice squeals again as her Mother continues to pose questions and moves her arms and body.

Sebastian

Sebastian Description:

Sebastian’s Mother is holding him so that his face is directly opposite hers. She rubs her head against his face and upper body. The Mother makes happy cooing noises and Sebastian mimics her in response.

David

David Description:

David is sitting upright on a play mat with his Mother holding on to him so he doesn’t fall. He is actively looking at his surroundings. His Mother watches him all the time and speaks to him gently. David continues to look around and babbles back.

Rebecca

Rebecca Description:

Rebecca is sitting on her Mother’s knee and is using both hands to drink from a feeding cup. Her Mother talks to her, all the time praising Rebecca for drinking unaided. Rebecca looks around all the time.

We would like you to watch this short video clip of babies communicating with their parents. While you are watching, make a note of the facial expressions of the babies.

- What kind of emotions do you think they are expressing?

You could use the response box for your notes – only you will see them.

Comment

Was it easy for you to identify the different facial or body expressions and attach an emotion to them? Certainly, happiness is quite easy to spot, but what about something like ‘anticipation’? Did you think that some babies showed more of one emotion than others?

Did you notice how attentive James was, keeping his eyes on his mother’s face? Alice was very vocal and communicative. Rebecca seemed to be anticipating the toy popping out and got quite excited while waiting. Sebastian made eye contact and mouth movements to his mother, and David babbled away and initiated frequent conversations.

It was easy to see how the older babies initiated communication. David, for example, was quite vocal and Rebecca was very demonstrative, waving her arms and bouncing up and down. Sometimes it may not be clear that a baby is actually starting communication rather than responding to something an adult has started off with them.

But did you notice, towards the beginning of the clip, how James, who was only 10 weeks old, raised both hands and made mouthing movements and again raised his hand at the end? Although these kinds of movements could be thought of as largely uncontrolled, researchers have found them common and predictable enough to conclude that even babies of this age initiate communication.

Interaction with adults is an important stage in the development of a baby’s communication skills. The babies in the video clip were having conversations with their mothers – for example, what Alice’s mother was saying when showing her the doll. This kind of talking – where there is exaggerated use of words and syllables and much repetition – is called ‘parentese’ by child psychologists. It is important because it introduces babies to patterns in their language and establishes familiar routines for them.

In their long-term study analysing the verbal interactions between parents and their children, Hart and Risley (1999, cited in Roberts, 2009) identified five specific ways that parents talked to children that consistently had the most positive impact on the children’s development, and their long-term verbal ability:

- they just talked, generally using a wide vocabulary as part of daily life

- they tried to be nice, expressing praise and acceptance and few negative commands

- they told children about things, using language with a high information content

- they gave children choices, asking them their opinion rather than simply telling them what to do

- they listened, responding to them rather than ignoring what they said or making demands.

It seems clear from these five bullet points that if you talk to children in an encouraging, informative and positive manner, you are helping them to develop the all-important skills of speaking and listening. It is these skills that help children to develop language and learn to read.

You have seen how adults can play a key role in a child’s development from a very young age and there is no reason why the five specific ways of talking to children (identified above) should not form the basis of good practice at all levels of education.

1.1 Developing language skills

You are now going to switch your focus to toddlers and nursery-age children. We’d like you to look at how Claire, a nursery worker, made use of the natural environment around her setting to develop the language skills of some of the children in her care.

Activity 2

Part 1

Transcript

Nature trail

In the video above, Claire is taking four children to a ‘forest’ to explore the area and to observe insects and birds. As you watch, try to identify and record examples of how Claire talked to the children, using the five specific ways of positively communicating with children identified by Hart and Risley (1999, cited in Roberts, 2009) in their study.

Give an example against each of the five specific ways to show how Claire has used them to communicate with the children. Some examples have been given in Table 1 to get you started. You can either draw your own table or use the version we have provided in a Word document. You may need to watch the video several times to catch what is said.

When you have finished, compare your observations with ours. You may not notice much conversation as part of daily life in the clip. This is because it has been recorded to show a nursery worker carrying out a particular activity, rather than an everyday conversation between a parent or carer and a child, as in the Hart and Risley study.

| Specific way of talking to children | Our example | Your example |

|---|---|---|

| Talking as part of everyday life | Step over the stick if you want to go a bit closer. | |

| Being nice | Shall I lift you up to have a look so you can see it a bit better? [kindly tone] | |

| Giving information | I have got a bug on me now. I have got a little fly on me, look. | |

| Giving choices | Shall we put the log back down then? | |

| Listening and responding | The birds, yeah. [in response to child’s answer] |

Comment

When you have finished completing Table 1, compare your observations with ours. Which part of the table did you find most difficult to complete? Were there more examples of one way of talking?

Table 2 shows more instances of how Claire communicated using the five specific ways of talking to children. These are not the only possible answers. You have probably found other examples.

| Specific way of talking to children | Further examples |

|---|---|

| Talking as part of everyday life | Jack come over here a minute and look. |

| Being nice | Let’s put it down carefully then so we don’t hurt them. |

| Giving information | I’ve got a bug on me now. I’ve got a little fly on me, look. |

| Giving choices | There look, that’s a different one isn’t it? |

| Listening and responding | Is it my pet? |

Part 2

Now think about how you would structure a similar activity in your own setting. What vocabulary would you choose? It doesn’t have to be about birds and plants.

You might also find it useful to use the five points listed above to analyse a conversation with young children in your setting. Remember that these early communications are an important foundation in the development of literacy. They are helping to build up vocabulary as well as introducing young children to different patterns of speech and language.

2 Moving from the early years to primary

You are now going to consider how literacy and reading are taught in primary schools. In 2006, the Rose Review of reading in the Early Years Foundation Stage and Key Stage 1 emphasised the importance of the development of literacy skills in preparing children in Reception and Year 1 of primary school.

The report emphasised the importance of literacy skills in laying the foundations for more structured approaches to reading in primary schools, such as phonics, an approach that breaks words into parts that represent separate sounds. The clear distinction between ‘literacy’ and ‘English lessons’ was made in Section 11 of the Rose Review (2006). Literacy skills are much broader and encompass speaking and listening across all of the curriculum.

The National Curriculum and the National Literacy Strategy

11. A distinction needs to be made between literacy and English. Literacy skills, that is, reading and writing (and the skills of speaking and listening on which they depend), are essential Cross-curricular skills: they are not subjects and are not confined to English lessons.

Learning support workers play a key role in speaking and listening to children and in so doing can make an important contribution to the development of these literacy skills, including reading, in all areas of the curriculum.

This section is designed to give you some ideas that you might like to try out in your own setting. You will use a case study to examine the attempts of one teacher to introduce an innovative approach to reading and to reflect on how this has helped to address the gender gap in her school.

The challenge of encouraging children to read is a big one because it is a fact that in England the weakest readers at age 10 are seven years behind the strongest. Children in the poorest families are the ones most unlikely to be able to read at age 11 because there is a tendency for them to come from families of lower socio-economic status and therefore may have less access to books and reading within the family (Ward, 2014).

Activity 3

Read the adapted extract below from the TES (Times Educational Supplement) online about the ‘reading gap’ in primary schools and then answer the questions that follow.

Campaign to end ‘shameful’ reading gap in primary schools

Figure 2 Child reading a bookAround 1.5 million children will leave primary school struggling to read by 2025 unless urgent action is taken, according to new research published today by a campaign group set up to eradicate illiteracy.

The report published by Save the Children, on behalf of the Read On Get On campaign, shows that England is one of the most unequal countries in Europe when it comes to children’s reading. [This inequality in reading ability has been referred to as the ‘reading gap’.]

The research suggests the UK economy could be £32bn worse off without action being taken to ensure 11-year-olds leave primary school as more competent readers.

In England, the weakest readers at age 10 are seven years behind the strongest – only Romania has a greater gap. And it is children in the poorest families who are the most likely to be unable to read well by the age of 11, says the charity.

The Read On Get On campaign, a coalition of charities, businesses and educationalists, is calling on all political parties to pledge to support the ’bold but achievable’ target of making sure every child born this year is able to read well by the time they leave primary aged 11 in 2025.

[…]

Last year, two in five children eligible for free school meals did not reach this level by the time they left primary school, compared to just one in five of those not on free school meals.

‘In Britain, primary education for children has been compulsory for at least the last 150 years,’ said Dame Julia Cleverdon, former chief executive of Business in the Community and chair of the Read On Get On campaign in the foreword to the report.

‘Yet to our shame, thousands of children leave primary school each year unable to read well enough to enjoy reading and to do it for pleasure, despite the best efforts of teachers around the country.’

The report compares the challenge to the eradication of polio and cholera, pointing out it is possible but only with high ambitions and long-term sustained action.

It calculates that if all primary schools were to improve at the same rate as the top 25 per cent, then by 2025 around 97 per cent of pupils would be reading well.

Russell Hobby, general secretary of heads' union the NAHT, said teachers were making impressive progress but universal literacy would depend on broadening the challenge beyond schools.

[…]

Justin Forsyth, chief executive of Save the Children, said: ‘Read On Get On is not just about teachers, charities and politicians – it’s about galvanising the nation so that parents, grandparents and volunteers play their part in teaching children to read.’

The campaign is calling on parents to read with young children for ten minutes a day, urges volunteers to sign up to help children with reading in their local school and calls on schools to lead the way locally.

- What do you think is meant by ‘the reading gap’?

- Why do you think the UK is so far down the international league tables?

Comment

From the TES extract you have just read, it appears that the ‘reading gap’ is linked to the inequalities in society. The reasons for this are complicated, but may include factors such as limited access to books in the family and parents not having the time or resources to read to children. If we are aware that there is a problem, we can work together to tackle the challenge.

This means parents, teaching assistants, teachers and all other support staff working together and sharing their expertise – in other words, you.

Two examples of positive action together are:

- The Read On Get On campaign, which aims to ensure that every child born today will read well by the age of 11 in 2025 and in which teaching assistants have a key role to play.

- A blog set up by a mum living in the USA, who shares her interest and expertise as a parent of a young child.

2.1 How is reading taught in primary school?

In a moment we will ask you to view a video in which you will see some children reading out loud and being helped by their teacher using a phonics approach to reading.

The phonics approach to reading is important because it is now the approach most favoured by the UK government. The government decided this after an important review of literacy standards (the Rose Review) was published in 2006, which looked at ways to halt falling literacy standards. The Rose Review concluded that the teaching of phonics should be enforced within the National Curriculum and this would lead to a boost in literacy levels. There are now a variety of strategies that have concentrated on a ‘heavy dose of phonics’ delivered by teachers in schools today (Dombey et al., 2010).

There are various approaches to teaching phonics. For example:

- analytic phonics, which looks at whole words and then breaks them down into component parts, e.g. dog as d-og

- synthetic (systematic) phonics, which starts with individual letter sounds and some combined letter sounds to create or build up the word, e.g. s-t-r-ee-t as street.

How does your school teach reading and develop children’s literacy? The next activity will start you thinking about this.

Activity 4

Transcript

Phonics without tears

In the video you will see some children reading out loud and being helped by their teacher using a phonics approach to reading.

- What does the video clip tell you about the phonic scheme being used in this school?

- Is this your school’s approach to reading? If yes, how effective is it?

- If you are not in a school, find out how a child close to you is learning to read.

Comment

In the video the school is using a systematic phonics scheme that involves actions and sounds. Phonics is essential in that it encourages children to be independent when working out their own reading and writing skills. If they know a particular sound, the children can attempt to work out another word on their own.

If they are learning words by rote the children don’t have the strategies to be able to work out new words. Phonics is a tool that enables the children to do the real work. It is helping children, not only to become decoders of print, but also to become someone who can infer meaning and engage with books in a critical sense.

Possible response to ‘own experience’ question

- My school uses the Jolly Phonic approach to reading. It is proving to be more effective than the previous ‘look and say’ method.

In spite of continued government support for the phonics approach, the United Kingdom Literacy Association (UKLA) (Dombey et al., 2010) has argued strongly for an ‘alternative way’ and highlighted the dangers of ‘putting all our literacy eggs into the phonics basket’. The UKLA has argued against a ‘one-size-suits-all’ approach to the teaching of reading at every stage and says that reading phonically is not the same as reading (Dombey et al., 2010).

2.2 New ways to encourage reading

Think of all the various forms of reading you do for different purposes on a daily basis. Perhaps we can encourage children’s reading in different ways to accommodate a wider range of interests to reflect today’s world of new information and communication technologies.

New digital technologies have brought exciting opportunities for children of all ages, and digital books can be downloaded from apps onto computers and tablets such as the iPad. There is a growing number of exciting apps that can stimulate parent and child interactivity in online reading and book sharing. However, not everyone recognises the benefits of these new technologies and some parents have concerns that their child is spending too much time on a computer rather than reading a traditional book.

Work done by Kucirkova et al. (2014) on the digital personalisation of books has shown that digital books provide alternative ways of interacting and engaging children, parents and teachers. According to Kucirkova et al. (2014), evidence has been mixed in relation to the role that digital books can play in literacy development. Digital books don’t always have the richness of vocabulary and grammar of print books, and parents don’t use as many helpful reading strategies while sharing digital books but concentrate more on IT skills. Nevertheless, digital books provide an exciting alternative way of interacting and engaging readers, teachers and parents. See for example:

If you are interested in the debates about children and digital technologies and whether they are a good or a bad thing, you might like to enrol on Childhood in the Digital Age, a free Open University module on FutureLearn.

2.3 How did you learn to read?

Being able to make the links between your studies, your own experiences and what you do in the classroom is an important part of becoming a reflective practitioner and of developing your professional skills. The next activity asks you to think about what it is like to be a child learning to read.

Activity 5

Think back to when you were a child and how you learned to read.

- How were you encouraged to read?

- Did you enjoy reading or did you find it a struggle?

- What sorts of books did you like or dislike?

- Can you remember a favourite book?

- Were books the only things you read?

- Do you think girls read more than boys?

- Do boys read different books than girls?

Before you read the case study in Topic 3 about how 8-year-old twins were encouraged to read, make a few notes in response to these questions.

Comment

Everyone will have their own answers to these questions. Your own experience of learning to read may affect how you encourage the children in your care to read.

3 Boys, girls and reading

In the following case study, Alex and Harry are lively 8-year-old twins with an older sister, Laura. She is 11 years old and an avid reader. Christine, their mother, is keen to foster a love of reading in the twins and is aware of how important it is to sit with them and read. This is easier said than done, not only because of lack of time, but also because the twins are very different.

Case study: Alex and Harry learn to read

When he is in the mood, Harry loves to sit beside Christine and look at books. He is starting to read quite fluently and enjoys spelling out unknown words, as he has been taught in school. Harry’s favourite book is Captain Underpants because it makes him laugh. This is a special time for both of them but Christine feels guilty about Alex because he is not getting the same attention.

Alex is a reluctant reader and appears to have little interest in books. He says about reading that ‘it’s boring’ and he never wants to unpack his school reader.

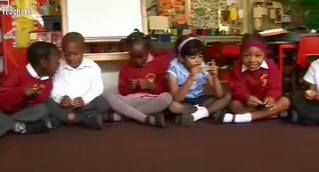

The boys’ teacher, Miss Fuller, has reassured Christine that Alex enjoys circle time, which often focuses on reading and literacy. Many primary schools use circle time where the focus is more on the children than the curriculum. The class sits with the teacher in a circle and ‘games’ are used to encourage cooperation, listening and speaking skills.

There are some general rules for circle time; for example:

- Everyone has the right to be heard and a duty to listen.

- There should be no ‘put-downs’. In the first stages it may be that the rule should be that all statements made should be positive.

- Everyone has the right to pass.

- Everything said should be confidential unless otherwise agreed.

It is a good way of developing peer relationships within the class. Very often a teaching assistant will also take part in this activity and they will model active listening skills for the children. Teaching assistants often position themselves next to or close by children who may need some additional support to benefit from circle time.

Miss Fuller has started to use this time to encourage the children to talk about books they have read. The children also listen to each other reading in class, which is known as peer reading. These activities have made reading more of a social activity and Alex’s peers are beginning to have an influence on his interest in reading. Miss Fuller has also informed Christine that reading is not just about books and Alex can develop his reading skills just as well on the computer, which he seems to enjoy more.

Alex’s teacher is confident that he will make progress in his reading because of the social interaction with his classmates and friends during circle time.

Christine is concerned about the difference in development and academic progress between Harry and Alex. She does think that their happiness is the most important thing but the nagging concern over Alex’s progress or lack of it resurfaces in her thoughts quite often. She thinks that Alex’s current teacher Miss Fuller is ‘a bit special’.

Christine believes that it is through a deep understanding of Alex’s needs and interests that Miss Fuller has been able to work some kind of magic. Since being in her class, Alex’s attitude and approach to being at school are now much better. This can also be attributed to the additional support Alex receives in school to develop his reading skills and interests. The school involved Christine in discussions about Alex’s ongoing progress and raised concerns that he might have special educational needs.

Special educational needs affect a child’s ability to learn and this may include their reading and writing – for example, if they have dyslexia. If a child has special educational needs they may require an education and health care (EHC) plan. As a teaching assistant you will be in an ideal position to raise concerns and you will be able to request that the local authority carries out an EHC on behalf of a child in your care. You will work in conjunction with the parents, teacher and any other support workers in deciding whether to request an EHC. Visit the government website gov.uk for more information about children with special educational needs.

Section 4 of this course looks at special educational needs and disabilities (SEND). You may find it helpful to study that section.

3.1 The gender gap: fact or fiction?

Refer back to the notes you made in Activity 5 in which you were invited to think about your own experiences of reading. One of the questions was ‘Do you think girls read more than boys?’ Your own experiences are a good basis for understanding children, but bear in mind that it is important to avoid generalisations. You may recall from the case study that the twins’ sister Laura was an avid and competent reader. This is not the case for all girls, and Harry has a different approach to reading than his brother Alex.

Much has been written about the ‘gender gap’ in primary education. Gender is the range of characteristics linked to the social differences between masculinity and femininity. There is evidence from research that supports the view that there is a difference between achievement in boys and girls. Moss (2007) found that boys thought of as poor readers spent less time on or avoided reading, so ensuring they maintained credibility with their peers. Girls meanwhile were happy to be seen reading easier books and to receive help from other experienced readers. By spending less time on reading, boys consequently fall further behind their peers so the problem becomes worse.

In 2010, tests in schools revealed that more girls were achieving higher levels of reading ability than boys. However, there was some evidence from Scotland that the synthetic phonics approach had improved boys’ reading (Johnston and Watson, 2005).

Some girls choose more challenging reading material for themselves. Contemporary books for girls in upper primary years include the Tracy Beaker series by Jacqueline Wilson. These and the plethora of vampire stories, such as the Twilight Saga by Stephanie Meyer, attract a pre-teen audience of able readers. Girls also share and discuss books much more readily, often forming reading groups similar to those that are popular with adults.

With growing awareness of the gender differences, efforts have been made to redress the balance. For example, a 2010 BBC TV series, Extraordinary School for Boys, explored different ways of engaging 11-year-old boys at primary school with learning, through concepts of risk and adventure.

By taking boys outside the classroom and involving them in learning through physical activities, the series attempted to harness that type of learning and channel it into learning within a classroom. It was led by Gareth Malone, who also challenged the stereotype that ‘boys don’t sing’ (The Choir: Boys Don’t Sing, broadcast in 2008). Gareth commented that ‘If school feels like a place where boys can take risks and push themselves and really challenge themselves, then they’ll be more engaged.’

Addressing the gender gap

Read this account written by Miss Fuller, the twins’ form teacher referred to in the case study. It is an example of some of the innovative work being undertaken in the twins’ primary school to address the gender gap. In year 4, children are 8 to 9 years old. Miss Fuller outlines how she sees the differences in reading in relation to Alex and Molly, who has been in Alex’s class since starting school aged 4.

Case study: Miss Fuller’s account

In the case of two typical children in my year 4 class, Molly and Alex, there are distinct differences in their attitudes towards reading and writing. Molly is an avid reader, with a natural love of books and stories. She brings her library books to school every day, changes her books regularly and independently and enjoys reading, both at home and at school. She shows an interest in her reading, chooses books that she enjoys and likes recording her thoughts and feelings on the books that she reads.

As Molly reads regularly and is enthusiastic, she drives her own love of reading. This has a positive effect on Molly’s understanding of her reading, as she thinks carefully about the stories she reads and reflects on her own thoughts and feelings towards her reading. This also affects Molly’s writing in school, as she is full of ideas and has a good understanding of how to structure her writing in order to make it interesting.

Alex would never say reading was his favourite school activity. He often enthusiastically chooses books from the library, but quickly loses interest if the book is too long, or does not have enough pictures. Alex regularly forgets to bring his library books to school and although his mother tries to read with him at home, they struggle to maintain a reading habit. As a result Alex’s reading patterns are erratic. This becomes a vicious circle, as the less regularly Alex reads the more quickly he loses interest.

Although both children read with me and teaching assistants at school, the differences in their motivation towards reading, at home and at school, have a significant impact on their confidence in literacy and their reading and writing ability.

Various strategies have been put in place in our school in order to reduce the gap in literacy between boys and girls, and in particular to inspire boys, such as Alex, to read and write.

The main strategy that I have found successful in engaging the boys to read and to write is to give them a distinct sense of purpose in each lesson. Molly tends to work to please the teacher, whereas Alex often wonders, ‘What is the point?’ With a distinct purpose for a lesson, and when collaboration is encouraged, Alex is engaged and both children are given a real-life reason for their learning.

For example, in a recent lesson, the children were asked to read a book and write a review on the book, in order to recommend the book to a younger child. The children were told that they would actually be reading their reviews and talking about the books with a class of younger children. This inspired and motivated both Molly and Alex to choose appropriate books for the children, to read them carefully and to write careful reviews. They also enjoyed using their ICT and art skills in order to present their reviews well.

The activity was successful as Alex and Molly enjoyed it, were motivated and saw the result of their efforts when reading to the excited younger children. Without realising it, both children were also using and improving their own literacy skills. The purpose of the learning was clear to both children and was regularly touched on through ‘mini plenaries’ (a session in which the teacher summarises what they have done) in each lesson, in order to keep the children motivated and on task.

Another important element in inspiring boys is the use of good quality, yet inspiring, reading material during guided reading sessions and literacy lessons. The quality of the texts is important in order to provide good quality examples of writing, yet the subject matter also needs to grab the boys’ attention. For example, I may choose spooky stories, or action stories, especially those with a boy protagonist.

At home, boys like Alex are encouraged, initially, to read anything that they are interested in, whether it be magazines, stories, comics or instructions for games. Gradually, Alex will be encouraged to choose books from the library that interest him, such as non-fiction books about a subject of interest, such as a favourite sport.

In order to make literacy lessons themselves more interesting, I present boys with inspirational stimulus, such as film clips, in order to provide the subject matter for a lesson. Along with the inspirational texts, the boys’ attention is grabbed and maintained. Use of role play and drama activities add to the interest and help to provide motivation for boys to want to read on, to find out what happens next in the story and to want to write their own versions of scenes from the story.

For example, in a recent lesson, Alex heard part of the story Peter Pan being read to him, watched some scenes from a film version of the story and made his own Peter Pan headdress, before acting out a battle scene from the story with his friends. Following this sequence of lessons, Alex was eager to read some more of the story himself, as well as to write about the scene he had acted, both as a narrative and as a play script.

In the same sequence of lessons, Molly also benefited from and engaged with the activities. In addition, she was able to take the work in her own direction by writing about a scene in the story that interested her.

The use of film as an inspirational stimulus has been extended in our school, through a FILMCLUB, one of a network of national clubs. Many of the children, including Molly and Alex, love the club, as it gives them a chance to relax and enjoy films with their friends. But I have also noticed that the club has had a positive impact on both children’s enjoyment in reading and writing.

My colleague and I carefully choose films that interest and engage the children, but which also give them an opportunity to experience different countries, cultures, languages and perspectives on life. The children are then encouraged to read about the films they have watched and to write their own film reviews. Alex has loved reading about the films on the club’s website and has enjoyed writing his own reviews, especially as he can then see his reviews posted on the club’s website.

An important aspect of your role as a teaching assistant is to reflect on your practice and to think about what has worked well, or not so well. In this account, Miss Fuller has reflected on her practice and has identified different things that have worked well with Alex and Molly.

Activity 6

Summarise what Miss Fuller said about Alex and his reading, and about the strategies she used to encourage him.

- How does Alex’s experiences of reading compare with those of Molly?

Try to identify any differences between the two children. Also think about the similarities between the two children, such as their love of FILMCLUB.

Make some notes in the box below and then read our comments.

Comment

Alex loses interest quickly in reading. This is a vicious circle because the less he reads, the more quickly he loses interest. He is an erratic reader.

Molly is an avid reader. She is full of ideas and reads library books, which she changes frequently. She is able to structure her writing and make it interesting.

However, both children enjoyed writing a book review of something they had read to recommend to younger children and they both enjoyed FILMCLUB.

Miss Fuller has put strategies in place to encourage reading. She gives a purpose to each lesson, such as a real-life reason for their learning. The children were asked to write book reviews for younger children and this improved their own learning.

Good quality and inspiring reading materials are important to Miss Fuller. Sometimes she uses an inspirational stimulus such as a film clip.

3.2 Literacy and reading in secondary school

The next activity shows you how some secondary schools continue to engage their pupils in literacy development, in ways that complement their understanding of the subjects taught at this level of the curriculum.

Activity 7

The two video clips below are examples from the USA of different strategies that are used in the development of literacy across the curriculum.

The first clip shows how Fairfax School has helped students with key words in different subjects, integrating literacy development throughout the curriculum. The second example looks at small guided reading groups, where pupils explore meaning together.

Transcript: Video 1: Best Practices: High School Reading Strategies

Reading strategies for high school students

Transcript: Video 2: 8th Grade Literacy: Small Group Guided Reading

Small Group Guided Reading – 8th Grade: North Middle School

If you are a teaching assistant in a secondary school, think about how the activities could be adapted for your own setting.

If you are not working in a secondary school but know children at this stage, try to find out more about what they are reading in relation to a specific subject and how vocabulary or key words are different from everyday language. An example from geography could include the following words: globalisation, urban and rural, spit, glacier, soil erosion, deforestation.

- How does your school help with literacy in the secondary curriculum?

- What words are linked to a secondary school subject that are different from everyday use?

Comment

Your answer will be dependent on your setting, and on whether your school has a policy in place to encourage reading and literacy. Whatever the policy is, that shouldn’t stop you from being creative and encouraging new ideas in children’s literacy.

What you have learned in this section

- Aspects of reading and literacy at three different stages of development. In the early years, you started by looking at how babies learn to interact with their parents or carers in early communication called ‘parentese’ and at an example of how one nursery assistant helped to develop the vocabulary of the children in her setting. Secondly, you went on to look at some of the issues in reading and literacy in primary school. Thirdly, you explored some of the challenges of reading and literacy that remain at secondary level.

- The ‘reading gap’ is linked to inequalities in society, and measures are being implemented to overcome it. The ‘gender gap’ is where there are differences between boys and girls in their approaches to reading and literacy. Miss Fuller’s account gave you an example of some innovative strategies used in one school to stimulate reading.

- In secondary school, the emphasis is less on reading and literacy per se and more on National Curriculum subjects. Some children still struggle with reading, and two examples from YouTube of American schools show that there are ways to integrate literacy and reading skills in subject-specific lessons.

- To think about how the topics in this section relate to your own practice: how making the links between your own experience, your studies and the setting in which you work helps you to become a reflective practitioner.

Section 2 quiz

Well done, you have now reached the end of Section 2 of Supporting children’s development, and it is time to attempt the assessment questions. This is designed to be a fun activity to help consolidate your learning.

There are only five questions, and if you get at least four correct answers you will be able to download your badge for the ‘Encouraging reading’ section (plus you get more than one try!).

- I would like to try the Section 2 quiz to get my badge.

If you are studying this course using one of the alternative formats, please note that you will need to go online to take this quiz.

I’ve finished this section. What next?

You can now choose to move on to Section 3, Behavioural management, or to one of the other sections so you can continue collecting your badges.

If you feel that you’ve now got what you need from the course and don’t wish to attempt the quiz or continue collecting your badges, please visit the Taking my learning further section. There you can reflect on what you have learned and find suggestions of further learning opportunities.

We would love to know what you thought of the course and how you plan to use what you have learned. Your feedback is anonymous and will help us to improve our offer.

- Take our Open University end-of-course survey.

References

Acknowledgements

This free course was written by Isobel Shelton and Sue McKeogh (staff tutors at The Open University). Contributions were made by Katie Harrison (teacher and member of the ATL Union).

Except for third party materials and otherwise stated (see terms and conditions), this content is made available under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 Licence.

The material acknowledged below is Proprietary and used under licence (not subject to Creative Commons Licence). Grateful acknowledgement is made to the following sources for permission to reproduce material in this free course:

Every effort has been made to contact copyright owners. If any have been inadvertently overlooked, the publishers will be pleased to make the necessary arrangements at the first opportunity.

Figures

Figure 1: Christina Kennedy/Alamy

Figure 2: Ron Levine/Getty Images

Figure 3: © The Open University

Figure 4: © The Open University

Figure 5: © The Open University

Videos

Activity 7

Video 1 transcript from Best Practices: High School Reading Strategies, Fairfax Network - Fairfax County Public Schools

Video 2 transcript from 8th Grade Literacy: Small Group Guided Reading (North MS) APSK12 Video