Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Tuesday, 10 February 2026, 9:01 PM

Behavioural management

Introduction

In this section you will be looking at behaviour management in primary and secondary schools. But what do we mean by ‘behaviour management’?

Behaviour management is vitally important within the classroom. It is not just about punishing unwanted behaviour or even rewarding desired behaviour. Rather it is about having strategies in place to support children to behave in ways that help them gain the most from their schooling. Oxley (2015) considers that building positive learning relationships and intrinsically motivating children to learn are important for effective behaviour management. ‘Intrinsically’ is important here as it is about children being motivated for reasons inside the person, such as for enjoyment, or because it makes them feel better about themselves; as opposed to extrinsic motivations, such as stickers, money, etc.

This subject has been divided into three topics:

- Child reactions looks at children’s reactions – the forms of behaviour children might present within a school setting and the reasons why they might behave in certain ways.

- Managing a class or a group looks at different approaches to managing children’s behaviour.

- Recognising behavioural issues focuses on how mental health issues may affect a child’s behaviour.

Learning outcomes

By completing this section and the associated quiz, you will:

be able to identify behaviour management techniques used in schools

develop an awareness or understanding of undesirable behaviours and the possible reasons for such behaviours.

1 Children’s behaviour

Jon Richards, UNISON’s head of education (cited in Bennett, 2015a) notes a few simple truths about children’s behaviour:

- Everyone experiences difficult behaviour at school

- Children, like all people, can be selfish, cruel, kind and amazing

- It isn’t your fault if they misbehave, but it is your responsibility to act if they do

- Most students will be happy to abide by rules that are fair, consistent and proportionate

- Almost all students prefer to be in a school where the adults take behaviour seriously.

Activity 1

List five undesirable behaviours children engage in, in your setting.

Comment

You may have noted some or all of the following behaviours:

- damaging property

- lying

- making silly noises or clowning around

- using abusive language

- talking back to staff

- not listening

- running indoors, rather than walking.

What one person considers to be undesirable, another person may consider acceptable. You might, therefore, have been surprised by some of the behaviours in our list. You might like to reflect on why these behaviours could be considered undesirable.

There are likely to be behaviours listed that are easy to view as undesirable because they put a child’s safety at risk, or they are disruptive and affect children’s ability to learn or interact with others.

As you work through this behavioural management section you may find it helpful to look back at the responses you have given and reflect on how these behaviours could be managed in a school setting.

1.1 Why might children behave in certain ways?

As a teaching assistant, understanding what makes children behave in the ways they do can help you to support the teacher in the classroom.

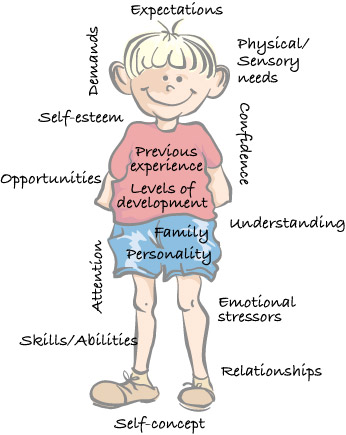

Figure 1 suggests that the root causes of behaviour are often complex and multifaceted. The child may not know himself why he is finding it difficult to do what he has been asked to do, and the adults in his life may not know either. Listening to children and helping them to both understand and talk about their feelings, as well as trying to see things from the child’s point of view, are vital skills that many adults need to learn or relearn.

The next activity describes a scenario to help you reflect on the reasons why a child may behave in an undesirable way.

Activity 2

Part 1

Read the following case study about Kyle. Read it once all the way through to familiarise yourself with Kyle’s situation.

Case study: Kyle’s behaviour

Kyle knew that he wasn’t supposed to use his mobile phone during lessons. Yet here he was at 3.30pm, the end of the school day, and he was trudging down the corridor to another detention. It wasn’t his fault he had arrived late to the lesson, and he felt a smouldering anger towards the teacher who made a sarcastic comment about the time as Kyle sidled into the room, trying to remain unnoticed.

He would like to see how that teacher managed after a sleepless night with his baby sister screaming and his mum arguing with her latest boyfriend. When the morning finally arrived, there was no sign of his school uniform in the chaos of the laundry pile and, glancing in at the barren fridge, Kyle knew that breakfast was simply not going to happen.

When he did get to school, the work for the lesson had already been handed out, and Kyle stared at the worksheet in front of him uncomprehendingly, silently asking himself why on earth he needed to know what 2n + 3y equals. He glanced over at the teacher, considering asking for help, but the teacher was with someone else at that moment.

Slumping down in his seat, Kyle pulled his mobile phone out of his pocket and started texting. The shout from the teacher interrupted this as he stormed over to Kyle and demanded that he put his phone away and get on with the work. Sullenly returning his phone to his pocket, Kyle turned back to the worksheet, no more comprehending than he had been before, and now with the prospect of yet another detention after school weighing him down.

1.2 Goals of misbehaviour

Rudolph Dreikurs (1897–1972), a child psychiatrist and educator, believed that all humans, as social beings, want to belong and be accepted by others. He identified four goals for misbehaviour:

- attention

- power

- revenge

- display of inadequacy.

As a teaching assistant, developing an understanding of why children might behave in the ways they do can help you to be more objective and calm in your reactions to undesirable behaviour. Table 1 offers possible reasons for children’s behaviours and how you may feel and react. It also suggests alternative ways in which you could deal with the situation.

| Child’s faulty belief | Child’s goal | Adult’s feeling and reaction | Child’s response to adult’s attempts at correction | Alternatives for adults |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| I belong only when I am being noticed or served. | Attention | Feeling: Annoyed. Reaction: Tendency to remind and coax. | Temporarily stops misbehaviour. Later resumes same behaviour or disturbs in another way. | Ignore misbehaviour when possible. Give attention for positive behaviour when the child is not making a bid for it. Avoid undue service. Realise that reminding, punishing, rewarding, coaxing and service are undue attention. |

| I belong only when I am in control or am boss, or I am proving no one can boss me! | Power | Feeling: Angry; provoked; as if one’s authority is threatened. Reaction: Tendency to fight or give in. | Active – or passive – aggressive misbehaviour is intensified, or child submits with ‘defiant compliance’. | Withdraw from conflict. Help the child see how to use power constructively by appealing for the child’s help and enlisting cooperation. Realise that fighting or giving in only increases the child’s desire for power. |

| I belong only by hurting others as I feel hurt. I cannot be loved. | Revenge | Feeling: Deeply hurt. Reaction: Tendency to retaliate and get even. | Seeks further revenge by intensifying misbehaviour or choosing another weapon. | Avoid feeling hurt. Avoid punishment and retaliation. Build trusting relationship; convince child that he or she is loved. |

| I belong only by convincing others not to expect anything from me; I am unable; I am helpless. | Display of inadequacy | Feeling: Despair, hopelessness – ‘I give up’. Reaction: Tendency to agree with the child that nothing can be done. | Passively responds or fails to respond to whatever is done. Shows no improvement. | Stop all criticism. Encourage any positive attempt no matter how small; focus on assets. Above all, don’t be hooked into pity, and don’t give up. |

Activity 3

Return to the account of Kyle’s behaviour in Activity 2 and use the goals of misbehaviour given in Table 1 to consider why he might have behaved in the way he did. Jot down some ideas in the box.

Comment

Maybe your immediate thought was that Kyle’s behaviour was attention-seeking. It perhaps depends on what you thought about the act of ‘slumping down in his seat’. Did you think that Kyle was trying to become invisible? Or did you view this as a defiant act linked to power, deliberately showing that Kyle didn’t care what the teacher thought, or about what he was supposed to be doing?

Alternatively, maybe you identified Kyle’s behaviour as a result of a display of inadequacy, and that he was passively responding to the demand that he put his phone away. However, if this is the case, Kyle’s ‘faulty belief’ that he belongs only by convincing others not to expect anything from him and that he is helpless means that his schoolwork is unlikely to show any signs of improvement. Had the teacher responded differently, Kyle’s beliefs might change and lead to more positive outcomes.

Deciding on the goals of misbehaviour is not an easy task as our own values, beliefs and views influence how we react to different behaviours, and to different children. As such there is not a right or a wrong answer. Even Kyle might not be conscious of why he behaved as he did, and intervention from support services might be necessary to support him to manage his behaviour.

2 Managing a class or a group

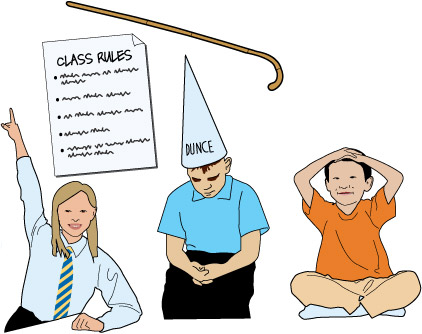

There have been many approaches to managing behaviour in the classroom. Depending on your cultural background, age, educational setting or even your choice of reading matter, you may have come across some or all of the techniques shown in Figure 2.

Certainly not all of these would be sanctioned in today’s climate of children’s rights and our knowledge of child psychology. However, there is no single agreed method of managing behaviour and different techniques work with different children.

2.1 Behaviour management in the classroom

Behaviour management is important in the classroom, not least because it creates an appropriate environment for learning to take place. If there are clear boundaries then children are enabled to develop positive behaviour, such as respect, towards each other. Behaviour management also supports learning in a safe and calm environment.

Activity 4

Take a few minutes to jot down the ways in which children’s behaviour is managed in your school or setting.

Comment

You may have noted an emphasis on reacting to children’s behaviour once it has occurred, or you may have identified examples where negative behaviour was pre-empted and children directed towards more positive behaviour.

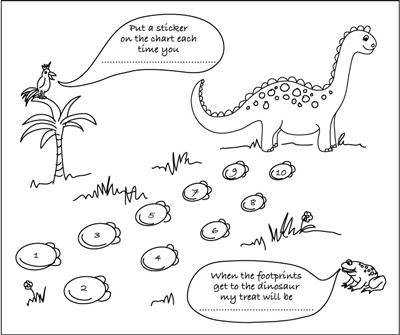

2.2 Managing behaviour through reward charts

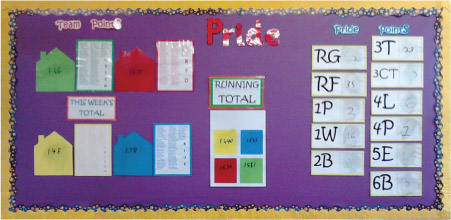

One way in which positive behaviour is encouraged, particularly with younger children, is through the use of reward charts. Some kind of system of sanctions and rewards is commonly used in secondary schools, although they may not use reward charts that focus on the individual, instead focusing more on group reward.

The article in the box below is a brief overview of the reward system, which we’d like you to read before doing the next activity.

Reward charts and behaviourism

The use of reward charts or similar reward systems is common, particularly with young children, not only at home but also in schools and by social workers working with children who have particular emotional or behavioural needs. The theory behind such methods stems from a branch of psychology called ‘behaviourism’.

During the past 30 years, behaviourism has had many forms but in simple terms it is based on the idea that children’s (and adults’) behaviour can be changed through learning and association. If a child associates certain behaviour with bad outcomes, they will avoid it. If they associate it with good outcomes, they will repeat it.

‘Punishments’ might include having adult attention temporarily withdrawn or being excluded from group activities for a short while, sometimes referred to as ‘time out’. ‘Rewards’ are focused on more than ‘punishments’, particularly with younger children, and rewards are used to encourage desired behaviour and discourage undesirable behaviour.

There has been increasing criticism of behavioural strategies with children, primarily on the basis that, if they work at all, the benefits or changes in behaviour are short-lived. Criticism has also been made due to the fact that often one person (the adult) is manipulating or coercing the behaviour of another, the child.

However, where the child is involved in discussions about behaviour, this interaction between parent and child may in itself eventually bring about a positive change. A reduction in family tension can result when parents’ focus is redirected towards encouraging positive achievements rather than getting cross.

Different forms of reward charts or reward systems

These can take different forms and have different names. They may be aimed at individuals, such as through a traffic light system, or at the whole class, such as through a pride point system that earns a whole class reward. However they are ‘packaged’, they all involve children having to ‘earn’ something they desire, such as ‘golden time’ or a sticker.

Although reward charts may not be used within secondary schools, it is common to have a system of sanctions and rewards (Department for Education (DfE), 2012). In some schools children earn merit points, which they then log online and save up to earn prizes that range from basic things like stationery to something bigger like cinema tickets.

Some secondary schools take the reward away from being a personal reward. Children may log points that they earn but each point is worth an amount – maybe 1p. At the end of the year or term, the points are converted to cash and the money goes to the school’s charity of the year.

Losing a privilege or an opportunity can be used as a ‘stick’ to achieve desired behaviour by punishing unwanted behaviour.

Are reward charts and ‘time out’ the end of the story?

While professionals (and parents) sometimes find strategies such as reward charts and ‘time out’ effective in managing some behaviour with some children, the benefits are generally limited and short-lived and may do long-term damage to an individual’s self-motivation (Kohn, 1999).

Very often it is difficult to enforce the chart, and children may need to be coaxed into doing whatever was agreed to gain the sticker, or other tangible item showing progress towards the goal. As time goes on the child may become bored and disappointed that they are not achieving the reward they were working towards.

Sometimes reward systems do not work because the child does not want to be singled out as different in some way from their peers. In addition, some older children may not log their points because the prizes are given out in assembly and some children think they are ‘too cool’ or are embarrassed by the attention, however positive.

Activity 5

Having read the article on reward charts now think about the following points:

- Do you think reward charts promote positive behaviour?

- What are the difficulties with using reward charts?

- If you use reward charts as a system for rewarding desired behaviour are there any changes you might suggest having read this article?

- If you don’t use reward charts, could they have a place in your school or setting?

Make some notes before reading our comments.

Comment

Your answers to the bullet points will be individual. Your personal experiences and your own views on how behaviour should be managed will impact on your reflections around the effectiveness of reward charts, and whether they could have a place in your setting.

In thinking about the difficulties with using reward charts, you might want to refer back to Dreikurs’s goals of misbehaviour in Table 1 and Kyle’s behaviour (Activity 3). Consider whether – if Kyle is trying to gain attention by doing something that he knows is not allowed (i.e. using his phone in lessons) – he should be allowed to experience the logical consequences of his behaviour. One issue to think about is whether this is appropriate when the logical consequences of Kyle’s behaviour may have a negative impact on his education and future employment opportunities. How might self-motivation be achieved?

2.3 SMART targets

For goals to be achievable, you need to have clear expectations of how you want the children to behave and a plan of how to implement the agreed goal. One way of doing this is to use SMART targets. SMART targets will help you to think through and clarify plans and setting goals, and make it easier to know what has been achieved over time.

Make it SMART:

- Specific: What exactly is the issue?

- Measurable: What would be a good outcome?

- Achievable: Is that possible? Yes (depending on the age of the child and the issues leading to the behaviour).

- Realistic: Is it realistic to expect this outcome given the classroom set up? Are there changes that could be made to the environment to make the desired behaviour more likely?

- Timely: When are you going to start?

And then add on an EA:

- Explicit: Explain to the children what will happen from now on and what is expected.

- Agreed: Get the children to agree. Does that sound OK to you? Are we going to do that?

- Agree the reward.

2.4 Minimising negative behaviour

To promote harmony in the classroom and create a suitable learning environment it is useful to think of ways to minimise opportunities for children to indulge in negative or disruptive behaviour. Activity 6 encourages you to think about ways of arranging the learning space to help children to concentrate on their learning rather than being disruptive.

Activity 6

Watch the video clip, ‘Boys will be boys’ [Transcript], straight through to start with. Then note how the classroom environment you work in is set out before watching the clip a second time. If you don’t currently work in a school, think about how the environment is set up in an education setting you do know.

Take notes on the following before reading our comments:

- How does the way the learning environment is set out in the clip minimise negative behaviour opportunities?

- How does the learning environment you work in help with behaviour management?

- Are there any improvements that could be made in your setting?

Comment

You may or may not agree with everything that is stated as fact in the video clip, such as ‘girls typically hear 2–4 times better than boys’ or that ‘boys have a unique sense of humour’. While a child’s gender may affect how they engage with the learning environment, children are individuals and do not always behave in ‘typical’ or stereotypical ways. Maturity, life experience, personality and many other factors also affect how a child responds in a particular situation.

Nevertheless, it is important to consider how adults can use their knowledge and understanding of behaviour triggers to create an environment that supports all children to behave ‘appropriately’.

Some of the examples you may have picked up from the video clip to minimise negative behaviour opportunities could include:

- providing a large enough space for play

- taking activities outside

- using headphones to lessen distractions

- giving warnings of a change of activity.

2.5 Maintaining classroom discipline

Tom Bennett, the author of Managing Difficult Behaviour in Schools (2015a), believes there are ten things every teacher should be doing to ensure order in the classroom.

- Don’t assume pupils know how you want them to behave.

- Have a seating plan.

- Be fair, consistent and proportionate.

- Know pupils’ names.

- Follow up.

- Don’t walk alone – use the line management if necessary.

- Don’t freak out.

- Get the parents involved.

- Be prepared and organised for lessons.

- Be the teacher, not their chum.

Activity 7

Reread the list of Tom Bennett’s (2015b) top ten tips for maintaining classroom discipline. These are the things that all staff should be doing to ensure order in the classroom.

Then watch a video clip on managing low-level disruption. Watch it straight through once without pausing or taking notes.

Transcript

Low-level disruption

Speaker: Tom Bennett, TES behaviour adviser

Low-level disruption is the thing that you will have to face as a teacher far more commonly than high-level disruption.

The thing that most teachers are most scared about is obviously the high-end levels of disruption. The tear-jerkers, the people who are rude, who swear, who are violent, and so on. Now, that does happen, particularly in some schools, but by far the most common type of misbehaviour you’ll have to deal with is the low-level misbehaviour.

Now, it’s called low-level misbehaviour, but it’s got a very high-level effect on your lessons. Low-level misbehaviour is like kryptonite to your lessons. It wears away. It erodes your teaching bit by bit. And the worst thing about it is, is that sometimes you don’t even notice the effect it’s having on your lesson.

What do I mean by low-level misbehaviour? I mean things like chatting, passing notes. I mean things like looking out the window when you should be working. I mean things like calling out when they should be putting their hand up. I mean things like getting out of the chair. Maybe playing with the curtains and so on when you haven’t asked them to. All the stuff that you have to stop and amend. Now, that stopping damages your lesson. It damages the flow and, of course, it takes away time from everybody else in the classroom. And that’s why low-level misbehaviour is actually very, very corrosive, like an acid, to your teaching.

If you ever film one of your lessons where you’ve got lots of low-level misbehaviour, what you’ll find is that about a third of your lesson is spent telling people to stop doing things they shouldn’t be doing, and getting people back on task. Now, ideally you want to be avoiding that.

So how do you avoid it? Well, there’s no quick and simple answer to this, but there is a simple explanation as to what you have to do. And what you have to do is establish very clear boundaries with the class from the offset. And let them know that those boundaries are going to be policed by you.

And the first time people start to cross those boundaries by, for example, talking over you, talking over their peers, passing notes, and so on, you need to make an issue of it. Warn them for it. And then let them know that something’s going to happen because of it.

Now, what you can do is you can also tacitly ignore the low-level misbehaviour in order to keep the lesson flowing. Now, that’s a strategy. I don’t just mean ignore the misbehaviour. What I mean is then return to the misbehaviour and how you’re going to deal with it when you're ready, not when they want you to be ready.

So if somebody is rocking in a chair or passing notes and so on, and you’re in the middle of telling the class what the task is, I sometimes don’t stop what I’m doing. I’ll finish explaining to the class and then, once I’ve done so, I then go to the pupil and say to them, all right, we need to have a conversation outside. Or, I need to see you after the lesson. Or, this is your last warning, you really shouldn’t be doing that. So do things in your time, not in their time. Otherwise the low-level misbehaviour starts to influence how you act in a classroom.

And one of the most important things you can do in a classroom is to show that you’re in control of yourself. After all, you can’t control anybody else, but you can control yourself. And by setting that example, and then by electrifying your boundaries with sanctions and praise, you can then lead the pupils into that kind of behaviour.

Now, that’s a slow process. You have to set the standard very high at first. And you have to police that standard quite intensely. And it will take a long time. There’s no getting around this.

You cannot police this kind of thing without speaking to a lot of kids after lessons and speaking to a lot of parents. But if you do that, and you do it rigorously at the start of your career with a group of children, you will be paid dividends in the future. In a sense, it’s an investment in the future of you and, best of all, in their education.

And that is how I deal with low-level disruption.

Now watch the clip a second time with the following questions in mind:

- How could you, as a teaching assistant, support the teacher to manage low-level disruption?

- How confident do you feel in supporting the teacher with this?

- What would help you to increase your level of confidence?

If you are not currently working as a teaching assistant, imagine a situation in which low-level disruption is occurring and apply the questions to this.

Make your notes before reading our comments.

Comment

Tom Bennett talks about the corrosive effect of children engaging in ‘little’ misbehaviours, such as chatting or passing notes, or being distracted. As a teaching assistant you are well placed to support the teacher in managing this type of behaviour. Perhaps you identified how you could gently remind children to listen, or praise a child for behaving appropriately. Focusing your comments on appropriate behaviour often has the effect of correcting the inappropriate behaviour of others, without the need to say anything to those children.

Tom Bennett noted that managing low-level disruption is something that takes time, and there is no ‘quick fix’. Equally, gaining the skills and knowledge – and confidence – to manage children’s behaviour effectively is something that takes time. Talking to the class teacher or to your mentor, or to the member of staff responsible for behaviour management in the school, will help you to develop your knowledge and skills in managing behaviour.

2.6 Involving children in behaviour management

The majority of children respond reasonably well to a system of rewards and punishments. However, such systems use extrinsic motivators, specifically aimed at controlling behaviour and ensuring compliance with what the teacher or school wants. Statistics show approaches using extrinsic motivation are not effective for all students (DfE, 2013).

Ideally children should be intrinsically motivated to learn, so that they do something, such as reading, for its own sake and because they want to, not just for reward (Kohn, 1999).

Activity 8

Read the edited extract below on alternatives to the behaviourist principles of sanctions and rewards and the use of restorative practice.

New voices: Do schools need lessons on motivation?

There are alternatives to the behaviourist principles of sanctions and rewards. One of these is restorative practice.

Originating in the criminal justice system, where it has been shown to be both more effective and less costly than traditional punitive approaches (Flanagan, 2014), restorative practice is based on building and maintaining relationships, repairing any harm caused, and working collaboratively on a way forward (Thorsborne & Blood, 2013). This approach takes commitment and support from all school staff and would initially be more time-consuming than continuing with a system of punishments and rewards. But in the long term this approach would be far more beneficial to the young people involved as they are given the opportunity to learn the skills they need to respond adaptively to life’s challenges and to develop emotional awareness and empathy. Schools that have implemented this approach have seen improvements on both social and academic measures, such as a decrease in school exclusions, a reduction in persistent absence, and increased achievement in both English and maths (Flanagan, 2014; Thorsborne & Blood, 2013).

The basic principle of the approach is that school staff are working with the young people to solve challenging behaviour issues, rather than imposing solutions on them. Research shows that choice and autonomy are key elements in building intrinsic motivation (Ryan & Deci, 2000). Enabling young people to participate in decision making about what happens to them in school is an effective way to engage students and teach valuable decision-making skills.

References

Flanagan, H. (2014, July). Restorative approaches. Presentation at training event for Cambridgeshire County Council, Over, Cambridgeshire, UK.

Ryan, R. & Deci, E. (2000). Intrinsic and extrinsic motivations. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 25(1), 54–67.

Thorsborne, M. & Blood, P. (2013). Implementing restorative practices in schools. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Now answer the following questions:

- What are your initial reactions to this approach?

- In your role as a teaching assistant, how could you support the implementation of this approach?

Make some notes before reading our comments.

Comment

A key element of restorative practice is the building of relationships. By working closely with children – often on a one-to-one basis – maybe you feel you already build relationships with children and that they already have the opportunity to talk to you and be listened to. As a result, perhaps you had a positive reaction to this approach.

Alternatively, you may have thought that it is a ‘nice idea’, but would take too much time to implement in practice. Also, depending on your views, you may or may not feel comfortable with the idea of working collaboratively with the children to resolve issues.

2.7 Optional readings and resources

If you have time and would like to explore this topic further, take a look at the resources below.

Reward systems do not work!

The following articles take the view that reward systems do not work. As you read them think about how convincing their arguments sound, and reflect on your own views on reward systems.

Mann, S. (2013) ‘Why “100% attendance awards” at school don’t work’, Huffington Post, 10 June [online]. Available at http://www.huffingtonpost.co.uk/ sandi-mann/ why-100-attendance-awards_b_3414693.html (accessed 17 December 2015).

Paton, G. (2009) ‘Classroom rewards “do not work”’, The Telegraph, 13 November. Available at http://www.telegraph.co.uk/ education/ 6563040/ Classroom-rewards-do-not-work-work.html (accessed 17 December 2015).

One school’s approach to managing pupil behaviour

If you want to explore how one particular school manages pupil behaviour, have a look at the information on their website.

TES behaviour management videos

The whole suite of behaviour management videos by Tom Bennett can be viewed on the TES website. Although aimed at teachers, the suggestions given by Tom Bennett may help you to understand the techniques a teacher may employ and enable you to be an effective support in managing behaviour in the classroom.

3 Recognising behavioural issues

There are many reasons for behavioural issues in children. In this topic we have chosen to focus on mental health issues as a cause of behaviour that might raise concerns.

One in ten children and young people aged 5 to 16 have a clinically diagnosed mental health disorder and around one in seven has less severe problems (DoH, 2013). Reports by organisations and charities working with children suggest these statistics have not changed significantly in the past 10 years. However, the importance of well-being and mental health is becoming much more recognised. So much so, the UK government appointed the first ever mental health champion for schools in 2015 to help raise awareness and reduce the stigma around young people’s mental health (DfE, 2015).

This focus on the well-being of children has produced a plethora of government reports on the topic. One of which, the Allen Report, Early Intervention: The Next Steps, quotes the Royal College of Psychiatrists as saying that:

Tackling mental health problems early in life will improve educational attainment, employment opportunities and physical health, and reduce the levels of substance misuse, self-harm and suicide, as well as family conflict and social deprivation. Overall, it will increase life expectancy, economic productivity, social functioning and quality of life. It will also have benefits across the generations.

3.1 What do we mean by mental health?

It is useful at this point to consider what we mean by the term ‘mental health’. In 2014, the World Health Organization (WHO) defined mental health as ‘a state of wellbeing in which an individual realises his or her own abilities [and] can cope with the normal stresses of life’. Poor mental health can be associated with change, stressful situations or lifestyle, as well as encompassing psychological or biological factors. The term ‘emotional well-being’ is synonymous with mental well-being (DoH, 2011) and is the term most often used within childcare provision by practitioners and within childcare policy documents.

The Children Act 2004 sets out the responsibilities on local authorities and their partners to cooperate to promote the well-being of children (this specifically includes their mental health and emotional well-being).

3.2 What triggers mental ill health?

Mental ill health can occur for all sorts of reasons. Sometimes a traumatic or stressful event – a death of a close family member, for example – may trigger mental ill health. However, often poor mental health occurs as a result of a combination of factors, or mental health declines over a period of time, perhaps due to prolonged bullying.

Activity 9

Note down the events or situations that could trigger mental health or emotional well-being issues in children. We have made a start in the box below.

When you’ve finished your list read our comments.

Comment

Young Minds is a UK charity committed to improving the emotional well-being and mental health of children and young people. Young Minds (2014) found that school-age children were most concerned about issues such as:

- fear of failure

- bullying

- body image

- the online environment

- sexual pressures

- employment prospects.

However, there is not always a clear cause or trigger for issues; and it is important to remember that children react in different ways to challenges in their lives, such as family relationship difficulties, exam pressures, or transitions.

Some children won’t be obviously affected by what is going on in their lives, while others may exhibit symptoms or behaviours that are worrying to parents and other adults they come into contact with. These symptoms or behaviours may be short term and nothing to worry about or they may denote a mental health issue.

3.3 Symptoms potentially indicating mental health issues

Schools are increasingly adding emotional health to policies and providing staff training around this issue. It can be fairly easy to tell when a child is physically ill – they may have a temperature above the norm or spots, for example. However, it can be much harder to determine mental illness, or lack of emotional well-being. This is not only because of the focus on feelings and the ability to cope with stress and life’s ‘happenings’, but the symptoms are much less obvious, particularly in the early stages.

One common mental disorder is anxiety. Anxiety can be triggered by a variety of things and as a teaching assistant you should have an understanding of how to support children when they are feeling anxious.

Anxiety and panic – signs and symptoms

Anxiety can cause both physical and emotional symptoms. This means it can affect how a person feels in their body and also health. Some of the symptoms are:

- feeling fearful or panicky

- feeling breathless, sweaty, or complaining of ‘butterflies’ or pains in the chest or stomach

- feeling tense, fidgety, using the toilet often.

These symptoms may come and go. Young children can’t tell you that they are anxious. They become irritable, tearful and clingy, have difficulty sleeping, and can wake in the night or have bad dreams. Anxiety can even cause a child to develop a headache, a stomach-ache or to feel sick.

Case study: Anxiety

‘I don’t know about you, but I have always been a worrier, like my grandmother. Every year, we would plan our family trip to India and it would start … worrying about the plane journey … worrying about falling ill, … and just before take-off I would get those horrible “butterflies”, sweaty hands and the feeling that I couldn’t breathe. Sometimes I would feel my heart beating and I thought I was dying or going “crazy”.

Last year, before my exams, my worrying got really bad. The pressure in secondary school has been high and everyone in my family has always done well and gone on to University, so I knew I had to study extra hard. It got so bad that I couldn’t concentrate. I felt shaky and nervous at school and even started to cry most days. I wasn’t sleeping well because I was so nervous and was too embarrassed to tell mum and dad.

I ended up pouring my heart out to the school nurse which was the best thing I ever did. She got in touch with my mum, and after seeing the GP, I went to see a team of specialists at the hospital.

Don’t worry … I didn’t want to be the “girl who sees the shrink” either but it’s not like that. The team can have all sorts of people like doctors, nurses, psychologists and social workers. They reassured me and helped me and my family to see that my symptoms were real (just like when you have asthma). I went on to have a talking therapy called CBT. This involves a number of weekly sessions with the therapist. I didn’t even need to take medication. Although I will always be a worrier I feel so much better, and I’m even looking forward to this year’s India trip.’

Activity 10

Having read the description above of the typical symptoms displayed by children with anxiety, now think about how as a teaching assistant you could support a child with anxiety. Make some notes and then read our comments.

Comment

When thinking about a child’s behaviour, you need to build up a picture rather than just focusing on a particular behaviour. In addition, think about the frequency or intensity of the behaviour and whether there are any obvious reasons for the behaviour.

You may have considered whether the child’s well-being was affected by the behaviour. For example, a child who is abnormally clingy and is reluctant to let their parent or carer leave them may find it difficult to form relationships or friendships with others. Or they may find it difficult to participate in normal social situations, which would affect their social and emotional development.

Some behaviours are appropriate at certain ages or stages of development but could mean a problem in an older child.

3.4 Listening to children

Listening to children is a key theme within services for young children. It is also an important element in any intervention to support children with mental health issues as it provides the opportunity for children to feel that their feelings matter and, thereby, raises their self-esteem. It also enables the adults involved to gain an understanding of the issues for the child.

Sometimes children may not be able to express themselves clearly, or they may find it difficult to talk about how they are feeling. They may benefit from accessing professional therapy sessions to help them explore their feelings and work through the challenges to their emotional well-being.

There are various types of therapy that may be offered, from conventional talking therapies, such as cognitive behaviour therapy, to therapies that enable children to express their feelings through play or art.

One way to get children to open up and discuss their worries and to find out how they are feeling is to share books with them that deal with ‘issues’.

Activity 11

Have a look through the books on the Royal College of Psychiatrists website and the Little Parachutes website.

Then look through the books in your school library or local library and identify two books that could be used to support children with difficulties, fears or worries they might have. Write a few lines to say how your chosen books could be used. We have given some examples below:

Everyone Has Feelings series by Picture Window Books

These books include titles such as Everyone Feels Angry Sometimes by Carl Mercer and Everyone Feels Sad Sometimes by Marcie Aboff. Each book focuses on one feeling and a situation associated with the feeling. The books help children to see there is a solution and that they can combat how they are feeling.

Michael Rosen’s Sad Book by Michael Rosen, illustrated by Quentin Blake. ISBN: 0744598982, Walker Books

Michael Rosen shares his sad feelings about his son, who died, and writes about how he tries to cope with this sad event in his life.

Misery Moo by Jeanne Willis, illustrated by Tony Ross. ISBN: 1842705261, Anderson

This story is about a cow who is so miserable Lamb finds her impossible to cheer up. In the end, though, Cow realises how important it is to have friends and to look for the best, not the worst, in things.

Voices in the Park by Anthony Browne. ISBN: 0552545643, Corgi

The illustrations can be used to discuss feelings with children and young people as a trip to the park is explored through the eyes of four different characters.

Beegu by Alexis Deacon. ISBN: 0099417448, Red Fox

Beegu is from outer space and this story explores what it feels like to be ignored and rejected by adults. There are few words but the illustrations convey its message and give plenty to talk about.

Reading Lights Comic books for 4–7 year olds and their teachers and parents. Available from Comic Company or the Royal College of Psychiatrists. Four colour books that address what it is like to be different, and provide a framework for parents, social workers and teachers to support children.

Books for older children to read themselves

There are a number of children’s authors who have written fiction books on real-life issues for children. Reading these stories can help children to work through and cope with their own life issues.

Authors include:

- Jacqueline Wilson

- Morris Gleitzman

- Lemony Snicket

Comment

There are lots of books for children that could be used as a basis for a discussion about feelings and to help a child understand the challenges in their life.

The Little Parachutes website has a range of relevant books for younger children and information related to fear and worries, some of which are downloadable. You may also have found that national support websites, such as MIND and the National Autistic Society, also provide useful reading lists and booklets.

Building up your own resource list and keeping it updated will help you to offer timely suggestions to older children and provide reading opportunities for younger children.

3.5 Optional readings and resources

If you have time and would like to explore this topic further, take a look at the resources below.

CAMHS Inside Out: A Young Person’s Guide to Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services

A booklet for any young person who wants to know more about what to expect from Community Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services.

DfE (2015) Mental Health and Behaviour in Schools: Departmental Advice for School Staff

This resource has information on promoting positive mental health, identification, interventions, facts about mental health problems in children and young people, types of mental health needs and sources of support and information.

Listening tips for practitioners: Literacy Trust and Participation Works

MindEd is a free educational resource on children and young people’s mental health. It offers a wide range of free e-learning sessions, one of which is ‘the aggressive/difficult child’. This particular session gives you the opportunity to recognise the signs and symptoms, and possible causes of aggressive and antisocial behaviour and to consider how such behaviour could be handled.

PSHE Association (supported by DfE) (2015) Preparing to Teach about Mental Health and Emotional Wellbeing.

Although this resource is primarily aimed at teachers planning a programme of lessons, there is some very useful information on a range of mental health issues such as eating disorders, anxiety and self-harm. It includes book lists and online sources of support towards the end of this document.

The Challenging Behaviour Foundation

Provides free downloadable information sheets focusing on challenging behaviour and children and adults with SEND.

The Mental Health Foundation websitehas descriptions of the typical symptoms displayed by children with different mental health disorders. If you visit their Mental Health A-Z you are able to search for mental health problems, topical issues and treatment options.

The Royal College of Psychiatrists website contains a wealth of readable, evidence-based information about mental health problems. The Parents and Youth Info Index is a good starting point for finding out information relevant to your role as a teaching assistant.

What you have learned in this section

- To think about some of the undesirable behaviours that children and young people might display in the classroom, and possible reasons for this behaviour. You started by identifying your own examples of undesirable behaviours, before thinking about what makes a behaviour undesirable. You then went on to consider Rudolph Dreikurs’ four goals of misbehaviour and used case studies to challenge your thinking about how you might deal with real-life scenarios.

- Approaches to behaviour management in the classroom. A key role of the teaching assistant is to support the teacher and to enable children to engage with learning. Two very different approaches to promoting positive behaviour in the classroom were introduced: reward charts and SMART targets, and restorative practice.

- That there are many reasons for behavioural issues in children, one of which is mental health issues. A case study focused on anxiety stimulated your thinking around behavioural symptoms that may be a cause for concern and introduced the importance of listening to children.

- Where to find additional resources. Behaviour management is a vast topic and so this section signposted to websites and resources that you can use as and when you have the need.

We hope you have enjoyed the variety of activities in this section and that it has raised your awareness of the complexity of managing children and young people’s behaviour. We also hope it has introduced you to some ideas and practices that may be new to you.

Section 3 quiz

Well done, you have now reached the end of Section 3 of Supporting children’s development, and it is time to attempt the assessment questions. This is designed to be a fun activity to help consolidate your learning.

There are only five questions, and if you get at least four correct answers you will be able to download your badge for the ‘Behavioural management’ section (plus you get more than one try!).

- I would like to try the Section 3 quiz to get my badge.

If you are studying this course using one of the alternative formats, please note that you will need to go online to take this quiz.

I’ve finished this section. What next?

You can now choose to move on to Section 4, Special needs, or to one of the other sections so you can continue collecting your badges.

If you feel that you’ve now got what you need from the course and don’t wish to attempt the quiz or continue collecting your badges, please visit the Taking my learning further section. There you can reflect on what you have learned and find suggestions of further learning opportunities.

We would love to know what you thought of the course and how you plan to use what you have learned. Your feedback is anonymous and will help us to improve our offer.

- Take our Open University end-of-course survey.

References

Acknowledgements

This free course was written by Isobel Shelton and Sue McKeogh (staff tutors at The Open University). Contributions were made by Katie Harrison (teacher and member of the ATL Union).

Except for third party materials and otherwise stated (see terms and conditions), this content is made available under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 Licence.

The material acknowledged below is Proprietary and used under licence (not subject to Creative Commons Licence). Grateful acknowledgement is made to the following sources for permission to reproduce material in this free course:

Every effort has been made to contact copyright owners. If any have been inadvertently overlooked, the publishers will be pleased to make the necessary arrangements at the first opportunity.

Figures

Figure 1: © The Open University

Figure 2: © The Open University

Figure 3: © The Open University

Figure 4: courtesy Kate Harrison (Teaching Assistant)

Video

Activity 6

Boys will be boys transcript: Georgia State University in ITunesU

Activity 7

TES video https://www.tes.com/ teaching-resource/ low-level-disruption-6344146 https://creativecommons.org/ licenses/ by-sa/ 2.0/