Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Saturday, 20 April 2024, 7:59 AM

Study Session 8 Cross-cutting Issues in the WASH Sector

Introduction

In this study session we broaden the scope away from the detail of the OWNP and look at some wider themes in the WASH sector. In the history of WASH programmes in Ethiopia, there are some issues that affect both planning and implementation but which have not been given sufficient attention, and this has contributed to the inequalities in WASH services. However, in the past few years these issues have become part of the main agenda in sector meetings and forums which the OWNP has been designed to address. This study session describes these issues in the WASH sector and explains why they are important. You will also learn how they are incorporated in implementing the OWNP in Ethiopia.

Learning Outcomes for Study Session 8

When you have studied this session, you should be able to:

8.1 Define and use correctly all of the key words printed in bold. (SAQ 8.1)

8.2 Identify the main cross-cutting issues in the WASH sector and explain why they are important. (SAQs 8.1 and 8.2)

8.3 Describe how these cross-cutting issues affect the implementation of the OWNP. (SAQ 8.3)

8.1 The concept of cross-cutting issues in the OWNP

It is commonly agreed that over that last few decades developments have been made in eradicating the world’s poor from absolute poverty. The economic growth and development success achieved by many countries is evidence of this. The joint efforts by the Ethiopian government, its development partners, the private sector and above all, the country’s citizens have made these great achievements possible. Despite this progress however, there are still millions of people who need the most basic services, including WASH. Some marginalised and unserved communities are still behind in benefiting from the success of WASH programmes. Part of the reason for this is the lack of attention given to some significant cross-cutting issues.

Cross-cutting issues are topics that affect all aspects of a programme (i.e. cut across) and therefore need special attention. They should beintegrated into all stages of programmes and projects, from planning through to impact assessment – but this has not always been the case.

There are many cross-cutting issues in the WASH sector. This study session focuses on some of the most important, namely: gender mainstreaming, community empowerment, sustainability, equity and inclusion and social accountability. These themes will be covered one by one in the following sections.

8.2 Gender mainstreaming

How would you define gender mainstreaming?

The term means to consider women’s perspectives and needs equally with men's at all times. (This was defined in Study Session 2.)

Gender is not just about the biological differences between men and women but refers to their different roles, rights, and responsibilities, and the relations between them (UNDESA, n.d.). It is generally associated with unequal power and access to resources because, in many societies and cultures, men tend to dominate and consider women to be subordinate. Gender mainstreaming is a process that aims to address this imbalance.

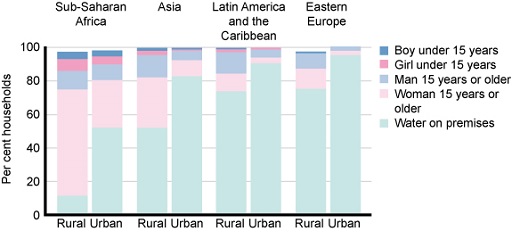

This inequality is illustrated in Figure 8.1 which shows, in four major regions of the world, who is the usual person in a household responsible for collecting water.

You can see from the graph that in rural areas of sub-Saharan Africa (which includes Ethiopia) women and girls are more than four times as likely to be the water collectors as men and boys. Sanitation is also a major challenge for gender inequality. If women and girls have no alternative to open defecation, they are likely to feel embarrassment and shame and may be vulnerable to attack, especially if they wait until dark.

In Ethiopia, gender issues have been included in policies and strategies for some time. You may recall from Study Session 2 that the Water Resources Management Policy (1999) and the Water Sector Strategy (2001) both included statements about gender mainstreaming. Even before that, the Ethiopian Women’s Policy of 1993 recognised the importance of integrating gender concerns and spelled out the government’s commitment to abolish laws and regulations that discriminated against women (MoLSA, 2012).

Despite these policies, women are still excluded from many of the privileges and opportunities available to men. Girls who should be in school are not properly attending their education because they are expected to help with fetching water and other domestic tasks. As a result, they perform less well than male students. Within a family, it is usually the males who take priority rather than females. Although women are actively involved in society and have an average working day of between 13 and 17 hours they usually earn far less than men and are frequently not paid at all (MoLSA, 2012). Participation in decision making outside the home and discussions about community priorities may also be limited. Because of cultural traditions, females are sometimes not allowed to talk in public, and even when they do participate, the opinions of women may not be accepted if they conflict with those of the men (World Bank 2001, cited in Yilmaz and Venugopal, 2008).

By increasing access to safe water and sanitation throughout the country, the OWNP will bring a big improvement to the position of women and girls. By no longer having to spend time collecting water, they will be free to do more productive work and attend school, with obvious benefits for them and their families (Figure 8.2).

The Programme document includes a recommendation that training associated with the OWNP should follow gender mainstreaming guidelines (OWNP, 2013). The Gender Mainstreaming Field Manual for Water Supply and Sanitation Projects (MoWR, 2005) provides practical advice on how to make sure that all stages of Water Supply and Sanitation (WSS) projects including planning, surveys, data collection, analysis, implementation, operations and maintenance (O&M) and monitoring and evaluation (M&E) are all undertaken with gender mainstreaming at the forefront.

What examples or WASH sector organisations can you think of where women are explicitly included?

You may have thought of WASHCOs, in which 50% of the members must be women. Another example could be rural Health Extension Workers (HEWs), all of whom are women or the Health Development Army (HDA), which is led by women.

8.3 Community empowerment

In Study Session 5 you read about participation as one of the essential components of good governance. Evidence shows that the participation of users in any development project, especially in the WASH sector, is of paramount importance to ensure sustainability and to create a sense of ownership. If communities have been fully involved in developing and implementing a WASH programme, they gain a sense of authority, or power, and this helps them to build confidence in their own capabilities. This is known as community empowerment.

In the past, the people planning WASH interventions did not always appreciate how important it was to engage communities in the process. Sometimes donors and non-governmental organisations (NGOs) would provide new services such as a well and pump without involving the local people in planning and developing the scheme. These schemes were installed without considering the opinions of the local community and then handed over to them to look after without giving attention to the organisational arrangements needed to maintain the scheme. Communities need to be involved and share responsibility for a scheme to make it successful and sustainable. Figure 8.3 shows a rural community which has worked together in their efforts to bring water to their village. Having invested their own time and energy, they will have an enduring sense of ownership of the scheme.

At the community level there is a requirement that WASHCOs for rural water schemes and WASH boards in urban settings should be formed to manage and maintain each water scheme. WASHCO members are elected by the community and, as you have learned, are constituted with a chair, secretary, treasurer and other officers. They are accountable to their communities and benefit greatly if they are given formal status so that they have a legal authority and can gain access to credit from micro-finance institutions.

The WASHCO’s duty is to plan and manage the community’s water and sanitation. The WASHCO is the prime agent of change in the process of mobilising people to undertake and sustain water and sanitation services. Communities also use the support of local artisans to implement water supply schemes.

8.4 Sustainability in WASH

You were introduced to the topic of sustainability in Study Session 3 where it was identified as one of the benefits of a sector-wide approach. It was defined as a concept referring to projects that gave due consideration to all factors (economic, social and environmental) and therefore were successful and long-lasting. For WASH, it is about whether or not water and sanitation services and good hygiene practices continue to work and deliver benefits over time (WaterAid, 2011). The emphasis is on lasting benefits rather than short-term advantages.

Sustainability is among the most critical aspects of service provision in the WASH sector. Whatever technology is applied or approaches are used, if the service delivery is not sustainable, all the investment made will be lost. WASH actors need to consider the sustainability of their project from the planning phase onwards.

Achieving sustainability of WASH schemes has been difficult for a number of inter-related reasons, which include:

- limited capacity (in the sense of knowledge, skills and material resources) of communities, local government institutions and other service providers to manage the systems once they are in place

- inadequate financial revenues (income) to cover the full operation and maintenance costs

- historical fragmented approach to service delivery by different actors in the WASH sector (WaterAid, 2011).

This last point is the main reason why the approach and principles of the OWNP should make a difference to sustainability. By harmonising and integrating the activities of the different actors in the ‘One Plan’ sector-wide approach, the historical fragmentation should be avoided.

The problems caused by being unable to sustain a water scheme are obvious. If the scheme fails, the community no longer has access to safe water. It is also problematic for the organisations who paid for the scheme in the first place. Any money spent on services which fail quickly is money ill-spent. However, in addition to financial concerns, the donors also have a responsibility to ensure continuing and appropriate support for ongoing management of the projects. All WASH sector actors, whether government or non-government, should be accountable to the communities who will use the services and manage the facilities. The implementation of WASH programme works needs to be aligned with building the capacity of the local stakeholders, especially local government, so that the sustainability of projects can be ensured after the other stakeholders have moved on.

The chances of a project being sustainable in the long term are greatly improved if a number of conditions are met. WaterAid (2011) summarises these conditions as a need for:

- real and continuing demand from the user communities, demonstrated by consistent use of improved water and sanitation services, and improved hygiene behaviour

- enough income at least to cover the recurrent costs for rural WASH and full cost recovery principles for urban WASH – this requires justifiable tariff settings that also consider the poorest and marginalised groups of the community who are often excluded

- a properly functioning management and maintenance system. This needs trained people with clearly defined roles and responsibilities, with appropriate institutions and organisations to support them, as well as tools, supply chains, transport and other equipment

- effective technical support and an enabling environment, especially for community-level structures and institutions

- due attention given to the local natural resources and environment that may affect the system, for example, awareness of the possible risk of flooding (Figure 8.4).

8.5 Equity and inclusion in WASH

Like sustainability, equity was introduced to you as one of the advantages of a sector-wide approach. Equity means the fair distribution and sharing of resources (natural or manmade) to benefit everyone equally. The OWNP includes mention of gender equity, which it links to gender mainstreaming and the need to ensure women are included in WASH schemes (OWNP, 2013). Equity also applies to other marginalised and disadvantaged sections of society. If someone is marginalised it means they are treated as insignificant or not important, or literally, pushed to the edges, or margins. Marginalised groups include people with disabilities of many different types, older people, children and people living with long-term illnesses including HIV/AIDS. It can also include residents of geographically hard-to-reach areas, internally displaced people, informal settlers and slum dwellers. All these vulnerable groups, for different reasons, may face barriers that restrict their access to WASH services (Figure 8.5).

The term equity is frequently linked with inclusion. Inclusion means the process of including these marginalised and unserved communities within, and not separate from, society as a whole. For WASH, it means considering their needs at all stages of WASH programmes, from planning to evaluation. Equity and inclusion are important cross-cutting issues in WASH because these groups of people have frequently been neglected in the past.

Look at Figure 8.6. Is the design of this facility helpful for Eniyew? How does the design of the cubicle make it easier for him to use? Will he have problems when he tries to wash his hands?

This design is quite helpful for him because the taps are low down, though he may have some difficulty in reaching them. It is good that the concrete surround is flat without any steps that would prevent him wheeling his chair right up to the taps. The cubicle has a raised seat and handrails which should help him transfer from his wheelchair.

Many of the WASH policies and programme documents that you have read about in previous study sessions include statements about the importance of access to water and sanitation for all. For example, the introduction of the WIF explicitly states: ‘This document is introducing WASH for all, which also includes disabled, disadvantaged and low-income communities’ (WIF, 2011). The main OWNP document says that the Programme ‘will promote and support social inclusion as an important strategy to enhance equity and reduce disparities in access to WASH services’ and describes ‘social inclusion’ as including ‘gender equity and mainstreaming, resettlement areas and areas with high concentrations of ethnic minorities and pastoralists and institutional WASH facilities that do not restrict access to handicapped and disabled persons’ (OWNP, 2013).

The challenge for the OWNP and its implementation is ensuring that this goal of ‘including all’ is properly integrated into plans and schemes and that all the diverse needs of the different groups of marginalised and vulnerable people are considered. For example, among disabled people, the needs of wheelchair users like Eniyew are not the same as people with other problems (Figure 8.7). Older people and others who need support rails to hold onto, people with poor sight, and disabled children are just a few of these groups with very specific needs. It is important that stakeholders with responsibility for planning and implementation recognise these varying needs and ensure that individual groups are not overlooked.

Look at Figure 8.7. How could these latrines be improved to make them more accessible to people with disabilities?

In Figure 8.7(a), the steep steps would be difficult for disabled people but could be improved if there was a handrail to hold onto. In Figure 8.7(b) the young woman has to leave her wheelchair outside the latrine cubicle and drag herself across the dirty floor. It could be improved if it was big enough for her to wheel her chair inside and had a raised seat with hand rails, similar to the one in Figure 8.6 (b). It would also be improved if the floor was kept clean.

You have already come across the idea of accountability in the OWNP. The revised Memorandum of Understanding of 2012 specified that the four WASH ministries should be accountable for their actions to each other and to others (see Study Session 3). In the vertical relationships within any organisation, people are accountable upwards to their managers and downwards to the levels below them in the hierarchy.

Social accountability in WASH is a concept that deals with the accountability of the service providers (government, development partners, CSOs, private sector, etc.) to the user communities. It means that community members, who are the primary beneficiaries, can ask questions and claim their right to a full account of the service(s) provided.

Social accountability means that the users have the opportunity to access all the information about projects implemented for their benefit. This information could include the source of funding, cost of the project, duration, design, effects on the livelihood of community members, effects on plants and animals, and the roles and responsibilities of the beneficiaries during and after project implementation. If appropriate mechanisms are in place, social accountability allows community members to obtain all the important information regarding the projects in order to enable them to assess the service provider’s performance.

Summary of Study Session 8

In Study Session 8, you have learned that:

- There are several cross-cutting issues in WASH that affect all aspects of WASH projects and which have not always been given sufficient attention in the past. They require the attention of all stakeholders at different levels and need to be considered from the earliest planning phases onwards – not just sometime in the middle or at the end.

- Major cross-cutting issues include gender mainstreaming, community empowerment, sustainability, equity and inclusion, and social accountability.

- Women and girls are usually responsible for water collection in Ethiopian households but their opinions and needs are not always given due attention. Legislation and policy have recognised the need for gender equity and mainstreaming for some time, but for many social and cultural reasons women’s voices are not always heard.

- As the ultimate beneficiaries of WASH projects, communities need to be empowered to participate fully in planning and implementation of WASH services. This will give the community a sense of ownership that will support the long-term sustainability of the schemes.

- Sustainability of WASH interventions is critical and has frequently been neglected in the past. Many hand pumps and other schemes no longer function for various interconnected reasons. For a scheme to be sustainable there needs to be a demand from users, sufficient income, effective management and maintenance, technical support and a realistic awareness of the local environment.

- WASH services need to be equitable and include all types of marginalised and vulnerable people with often widely differing needs.

- Social accountability is a responsibility of WASH service providers who must be accountable to user communities.

Self-Assessment Questions (SAQs) for Study Session 8

Now that you have completed this study session, you can assess how well you have achieved its Learning Outcomes by answering these questions.

SAQ 8.1 (tests Learning Outcome 8.1)

Identify the phrases from the jumbled up letters and write the correctly spelt words next to their definitions in the table below:

- ECMOPMOMWUENRIMTEYNT

- COLINUSIN

- LACISICYOTOUNCITABAL

| Phrase | Definition |

|---|---|

| Involving communities in the development and implementation of a programme or project. | |

| Making sure that marginalised and underserved communities are considered and incorporated within the programme or project. | |

| The idea that service providers are accountable to the user communities. Community members can ask questions and have a right to be answered. |

Answer

| Phrase | Definition |

|---|---|

| Community empowerment | Involving communities in the development and implementation of a programme or project. |

| Inclusion | Making sure that marginalised and underserved communities are considered and incorporated within the programme or project. |

| Social accountability | The idea that service providers are accountable to the user communities. Community members can ask questions and have a right to be answered. |

SAQ 8.2 (tests Learning Outcomes 8.1 and 8.2)

In addition to the phrases that appear in SAQ 8.1 there are two other cross-cutting issues that you will have seen in earlier study sessions. These are:

MAGINESANTERDEMIRNG and YABUSINTILASIT

Unscramble these two additional cross-cutting issues. Explain why each of the five issues you have named in your answers to SAQs 8.1 and 8.2 is important.

Answer

MAGINESNTRDEAEMIRNG = gender mainstreaming

SAUBSITLAIITNY = sustainability

All the cross-cutting issues are important when considering initiatives because ignoring them will lead to greater inequality and inefficiency.

Gender mainstreaming ensures participation by women and girls in all aspects of programme planning and implementation and supports equality between both genders.

Community empowerment will make projects more likely to succeed because it encourages a sense of ownership among the people who benefit from the scheme.

Sustainability of projects means that their benefits will be sustained into the future which provides long-term improvements for more people.

Inclusion of all marginalised, elderly, disabled and underserved communities is essential to achieve equitable WASH services for all.

Social accountability is important for community empowerment so that users of WASH services can be properly informed by the service providers.

SAQ 8.3 (tests Learning Outcome 8.3)

Which of the following statements are false? In each case explain why it is incorrect.

- A.It is more important that rural communities get adequate water supplies than urban ones.

- B.It is more important to get a ‘quick fix’ even if everyone does not understand why an activity is being conducted.

- C.Girls should be free to go to school rather than fetch water.

- D.It is important to engage communities with planning.

- E.There are some things about planning you need to keep to yourself and not share with the community or from other levels in your organisation.

Answer

A is false. Everyone has a right to a safe water supply although this may be harder to achieve for some rural and pastoral communities.

B is false. ‘Quick fixes’ are unlikely to be sustainable. It is important for communities to participate in decision making so they can contribute their local knowledge.

E is false. Sharing information with others in the spirit of transparency (which you read about in Study Session 5) will make for better decisions and more effective and sustainable projects.