Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Saturday, 14 February 2026, 7:25 PM

Study Session 10 Approaches to Implementing the OWNP

Introduction

The One WASH National Programme is new for Ethiopia. When it was introduced, no one had any previous experience of implementing a programme of this kind. It required new arrangements and adjustments to ways of working, i.e. new approaches and/or modalities, at federal, regional and woreda levels so that appropriate plans could be developed for putting the OWNP into practice.

In this study session you will learn about these new approaches and the conditions that need to exist within these various levels before OWNP implementation can take place. The study session describes some of the ways the implementation of the OWNP has been approached for water supply, sanitation and hygiene provision in both rural and urban settings, and in particular in schools and health facilities.

Learning Outcomes for Study Session 10

When you have studied this session, you should be able to:

10.1 Define and use correctly all of the key words printed in bold. (SAQs 10.1 and 10.2)

10.2 Describe the readiness criteria for implementing the OWNP at different levels. (SAQ 10.2)

10.3 Identify the implementation approaches for providing water supply and sanitation services. (SAQ 10.3)

10.4 Explain the difference between a community-managed and a woreda-managed project approach. (SAQ 10.4)

10.1 Readiness criteria at different levels

To implement any project, programme or activity you need to assess the situation before you start and consider if the right conditions for success exist. To give a simple example, if you were going shopping you would take some money, maybe a bag and possibly an umbrella. You could say these were your readiness criteria for shopping. Readiness criteria are conditions or things that need to exist or be done before starting an activity. For the OWNP, readiness criteria have been created for all the various implementing organisations at different levels of government, from federal down to local communities. The purpose of these criteria is to ensure that the right conditions exist for OWNP implementation or, in other words, that there is an enabling environment.

You were introduced to the concept of an ‘enabling environment’ in Study Session 5. Do you remember its definition?

An enabling environment means that the conditions are right for an activity or phenomenon to happen.

For the implementation of the OWNP, the enabling environment refers to the sum of conditions such as policies, laws, and physical infrastructure that allow (or limit) implementation of the OWNP at various levels. The readiness criteria for the OWNP have particular significance because they are tied to the release of funds. There is a requirement that conditions set out in the readiness criteria have to be met before money is disbursed and physical implementation can take place.

Readiness criteria for implementing the OWNP have been set from federal government down to kebele and community levels. The details vary at different levels but they follow a common pattern. For example, at the federal, regional and zonal levels the criteria include establishing the required organisational structure and recruiting staff for programme management units. Operational WASH budget accounts have to be set up with separate budget lines for all implementing organisations, i.e. each implementing ministry at federal level and each WASH sector bureau at regional level. Each level must also have a consolidated WASH plan prepared and approved by the appropriate higher authority. A consolidated WASH plan is a single plan that combines water supply, sanitation and hygiene schemes and integrates the separate plans from all WASH implementing organisations.

Readiness criteria at lower levels follow a similar pattern. All cities and towns are expected to have prepared a consolidated annual WASH plan and had this approved. They have to establish the necessary organisational structure (e.g. Town Water Board) and have appropriate staff in place. They need to organise their financial systems so there are separate budget lines for water supply and sanitation. They also need to ensure that staff and procedures for monitoring and evaluation (M&E) are established and that National WASH Inventory (NWI) data has been made available.

At woreda level, the criteria are much the same. They have to prepare WASH plans and budgets and have these approved by the woreda council. These plans might be for new small water schemes such as hand-dug wells in specific locations. The organisational structure that you read about in Study Session 7 must also be in place. For example, members of the Woreda WASH Team must be recruited. They also need to have separate budget lines and make NWI data available to all relevant stakeholders in the same way as towns and cities.

At kebele level, there also has to be a consolidated WASH plan. In rural areas, community WASH committees (WASHCOs) must be established. These must be formally recognised and registered at kebele or woreda level and have the appropriate gender-balanced membership and elected officers. WASHCOs must have opened a bank account for collecting and administering contributions from users of the WASH services. Like the higher levels, communities must have a single annual WASH plan and this must be approved by community and WASHCO members.

10.2 Rural WASH implementation approaches

The programme for rural settings is similar to that of urban environments in some respects, but different in others. Both include providing water, sanitation and hygiene services for their respective communities as well as for health facilities and schools, but the approaches to providing these services are different because the living conditions and needs of the people are different in urban and rural settings.

10.2.1 Rural water supply approaches

To address the low access to water supply in rural areas the Water Resources Management Policy (MoWR, 1999) supported decentralised management, and integrated and participatory approaches to providing improved water supply services. As you have read, this policy was part of the background to the OWNP which also encourages decentralisation of management and the involvement of different stakeholders, including NGOs and communities. The recovery of operation and maintenance (O&M) costs is also recognised and supported by this policy.

What makes the Water Resources Management Policy and OWNP similar?

Both documents support decentralised management, integration and the participatory approach of both stakeholders and the wider community.

In Study Session 6, you read that the OWNP’s rural water supply activities include various studies; constructing new point sources or small piped schemes with distribution systems, including multi-village schemes where appropriate; the rehabilitation of existing point sources and expanding small piped schemes. You were also introduced to the different approaches or modalities to implement and manage these activities. We will now describe these in a little more detail.

Woreda-managed project

The woreda-managed project (WMP) is a rural WASH implementation modality in which the Woreda WASH Team (WWT) takes the lead. They are responsible for administering funds allocated to woreda, kebele or the community for capital expenditure on water supply and sanitation activities. Although the kebele administration and WASHCOs are involved in project planning, implementation, monitoring and commissioning the project, the WWT is effectively the Project Manager and is responsible for contracting, procurement, inspection, quality control and handover to the community. Typically a WMP approach is used for small schemes such as spring development, hand pumps, and the software component of sanitation. (Software components are any activities that focus on knowledge, attitude and behavioural changes of the individual or the whole community. Hardware components are the physical parts of a scheme such as well linings, pumps, latrine slabs, lavatory pans, construction materials etc.)

The construction of WMP schemes is supervised by woreda staff and projects are transferred to the community after the design and implementation stages are completed by the woreda. This has traditionally resulted in very low community participation and ownership.

Community-managed project

The community-managed project (CMP) is a rural WASH implementation approach where communities are supported to undertake all stages of a project, from initiation through planning to implementation and management continuing into the future. These projects use funds that are transferred to, and managed by, the community. The major features of the CMP approach are:

- Fund Transfer: Funds for physical construction are transferred to the communities from woredas or through intermediaries selected by the communities, thus making communities responsible during the full project cycle from planning and implementation (including procurement of most materials and labour) to O&M.

- Community Project Management: The communities, through water and sanitation committees (WASHCOs), are responsible for the full development process through planning, financial management, implementation and maintenance. The communities contribute a minimum of 15% in cash or in kind (usually labour). WASHCOs manage not only community-generated funds, but also the government subsidy provided for capital expenditures.

- Procurement: A further aspect of community management is that the WASHCO is directly responsible for procuring (buying) the goods and services required for water scheme construction and installation.

The CMP mechanism is intended mainly for low-level technologies such as hand-dug wells and spring protection. An example of a community-managed project is the Debero-Garmojo water point (Figure 10.1). Debero-Garmojo is in the Abichugena woreda, Oromia region. The water point was constructed by local community with the support of the woreda administration and the government of Finland. The water comes from a spring and is piped into a collection tank which has three taps and serves 30 households. The WASHCO was responsible for its planning, procurement, contracting, management, and operation and maintenance.

NGO-managed project

As you know by now, non-governmental organisations (NGOs) are important stakeholders in the OWNP as donors, implementers and knowledge disseminators. Their funding and management arrangements vary considerably but, combined with national WASH principles and practices, they foster community initiatives, develop community leadership and require community investment in water supply projects. In some cases, NGOs administer external resources on behalf of the community. In others, they make external resources available to the community directly or through microfinance institutions to support construction and management.

NGOs have flexibility and are able to increase community involvement, ownership and accountability. NGO-supported projects follow procedures agreed between the NGO, its partners, the Ethiopian government and the region or woreda where the activities are located. They should comply with policies on cost-sharing, community contributions, reporting and monitoring indicators. NGOs are included in resource mapping at all levels and will be requested to provide information for preparing consolidated annual WASH plans and budgets. (Resource mapping is the identification of the sources and amounts of all possible funds for a project.) NGOs will also be requested to provide periodic progress reports on their projects to WASH Coordinators at various levels.

You have already seen several examples of NGO-managed projects in this Module. As discussed in Box 9.1 in the previous study session, the term NGO may be used loosely, and in this context is frequently applied to projects managed by organisations like UNICEF and the World Health Organization (Figure 10.2), which are not NGOs in the strict sense of the term.

Self-supply

Self-supply was defined in Study Session 6 as the construction and use of small-scale water schemes at household level, such as hand-dug wells. As stated in the manual prepared by Ministry of Water, Irrigation and Energy (MoWIE, 2014a) self-supply means ‘improvement to water supplies developed largely or wholly through user investment by households or small groups of households’. Self-supply involves households taking the lead in their own development and investing in the construction, upgrading and maintenance of their own water sources, water-lifting and treatment devices and storage facilities.

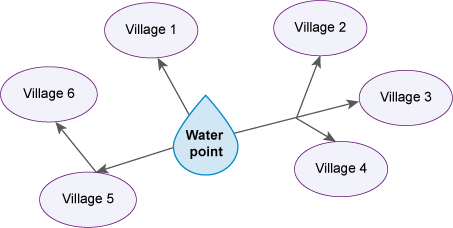

Multi-village water supply schemes

As the name suggests, these are schemes designed to provide water to several villages from a single source (Figure 10.3).

Regions and zones are mainly responsible for this type of scheme and they undertake all the studies, design, management, construction and supervision. These schemes are more complicated and construction requires higher-level technology to serve larger populations of up to 100,000 people in the combined villages. Multi-village water supply schemes will be supported under certain conditions, provided that feasibility studies verify that the proposed sources are adequate and that the schemes can be socially, technically and financially sustainable.

10.2.2 Rural sanitation and hygiene promotion

Currently there are a number of different approaches to promoting rural community sanitation and hygiene in Ethiopia. We will highlight two of the most important: community-led total sanitation and hygiene, and sanitation marketing.

Community-led total sanitation and hygiene

Community-led total sanitation (CLTS) is an approach which emphasises changing the behaviour of all people in a community in order to stop open defecation and encourage good hygiene practices in and around the home. CLTS was introduced in Ethiopia following a hands-on workshop in October 2006, organised by Vita, an Irish international development agency working in the Horn of Africa, and led by Dr. Kamal Kar (Figure 10.4). The Federal Ministry of Health had taken the initiative to use this approach as the main tool to improve rural sanitation by training Health Extension Workers (HEWs) in the technique. Since that time, the approach has been developed and renamed in Ethiopia to explicitly include hygiene and is now known as community-led total sanitation and hygiene (CLTSH).

The aim of CLTSH is to achieve open defecation free (ODF) status. This is awarded to villages and communities when they have achieved the situation whereby everyone has access to a latrine and no one defecates in the open at any time. The award of ODF status is cause for great celebration in the community (Figure 10.5). ODF status is achieved through a process of social awakening stimulated by facilitators from within or outside the community. The approach concentrates on the behaviour of the community as a whole rather than on individuals.

The CLTSH process involves trained facilitators working with communities to inspire and empower them to stop open defecation and to build and use latrines for themselves. The facilitators encourage people to take responsibility and consider their own behaviour rather than rely on external subsidies to buy hardware such as latrine slabs. Community members come together with the facilitators in group discussions to analyse the extent of open defecation in and around the village (Figure 10.6). They consider the implications of this for faecal-oral contamination and the resulting detrimental impact on human health that could affect every one of them.

The CLTSH approach works by creating a sense of disgust and shame among the community in a stage in the process called triggering or igniting. The process brings them collectively to the realisation that they quite literally will be eating one another’s ‘shit’ if open defecation continues. When they realise this shocking fact, the people become very enthusiastic about taking action to improve the sanitation situation in the community (Kar, 2005).

Sanitation marketing

Since the introduction of CLTSH, significant numbers of households have gained access to self-constructed basic latrines. However, many self-constructed latrines fall short of fulfilling the minimum standard of improved sanitation and hygiene facilities, as shown in Figure 10.7. This is one of the reasons for introducing sanitation marketing.

Why is the latrine shown in Figure 10.7 inadequate?

The pit is covered with logs rather than a slab. This will not provide separation between the people using the latrine and their waste. It is unstable and difficult to find a secure footing and is likely to break and collapse while someone is using it. Also there is no proper infrastructure around the pit to provide privacy.

Sanitation marketing is a relatively new approach to improving sanitation provision and does not have a single precise definition. The Water and Sanitation Program’s Introductory Guide to Sanitation Marketing explains that ‘some practitioners define sanitation marketing as strengthening supply by building capacity of the local private sector; others discuss it in terms of “selling sanitation” by using commercial marketing techniques to motivate households to build toilets’ (Devine and Kullman, 2012).

In Ethiopia, the National Sanitation Marketing Guideline defines sanitation marketing as ‘satisfying improved sanitation requirements (both demand and supply) through social and commercial marketing process as opposed to a welfare package’ (MoH, 2013). The national guideline sets out three pillars for the approach which are:

- Strengthening an enabling environment for sanitation marketing programme.

- Creating access for improved sanitation technology options.

- Generating demand for improved sanitation technology options (MoH, 2013).

In practice this approach includes a range of different activities that encourage people to build latrines and adopt good hygiene behaviour and also to create business and commercial opportunities. An important feature is that new sanitation services are not provided for free. Figure 10.8 shows an example of a sanitation marketing enterprise where latrine slabs are constructed for sale.

10.3 Pastoralist WASH

Pastoral communities generally have limited access to water supply and consequently, improved sanitation and hygiene practices also tend to be poor. Pastoral communities (in Somali, Afar and parts of Tigray, Oromia and SNNPR regions) also require water for grazing their cattle and other animals. This means that, where hydrological and hydro-geological conditions permit, water supply schemes should be constructed close to pasture lands and along migration routes.

In areas with natural resource scarcity, there is a risk that water development may trigger underlying conflicts over land ownership and access to resources, especially during dry periods or droughts. The development of water supply schemes in pastoralist areas must be sensitive to these possible conflicts and pay particular attention to the timing and quality of community consultation at every stage of the project cycle.

Implementation in pastoral areas is similar to the approaches mentioned above for the rural WASH programme except that it requires closer coordination with schemes designed to respond to emergency WASH situations.

10.4 Urban WASH

In Study Session 6 you learned about the categories of town for the urban WASH component of the OWNP. These are repeated in Table 10.1.

| Category | Description |

|---|---|

| 1 | Towns/cities having utilities managed by a Water Board |

| 2 | Towns/cities having utilities but not managed by a Water Board |

| 3 | Small towns with water supply systems managed by WASHCOs or towns without a water supply system at all |

The OWNP sets out two modalities for implementing the urban WASH component, which refer principally to the funding arrangements (described further in Study Session 12). These are:

- Grant financing for capacity building, planning and improvements to administration and management systems (i.e. financial support from a donor, which is not paid back).

- Soft loan financing for water supply expansion (i.e. a loan from foreign government or international financing institution, such as the World Bank, to be paid back but with a minimal interest rate).

Accordingly, the process and institutional arrangements differ. At town level there are two WASH structures and processes: one for water supply and one for urban sanitation and hygiene. Both will be integrated in the consolidated annual WASH plan to be approved by the City Council or Town Board.

10.5 Institutional WASH

As you know, this component of the OWNP is about schools and health facilities. The OWNP supports the construction or rehabilitation of water supply facilities and latrines at schools (primary and secondary) and health facilities. It also proposes to support school curriculum by producing visual aids on hygiene and sanitation, using educational materials to promote good sanitation and hygiene practices, and supporting participation in school health clubs and events like Global Handwashing Day. The Ministry of Education, through its regional/city bureaus and woreda/town education offices is responsible for implementing the Programme’s activities in schools. WASH activities can also be combined with other activities such as vegetable gardening to provide additional benefits to schools and possibility to support learning about nutrition. Through its bureaus and local offices, the Ministry of Health is responsible for WASH construction activities in health facilities. For both schools and health facilities, implementation may be through either woreda-managed project (WMP), community-managed project (CMP), or NGO-managed modalities.

In line with this, manuals for the design and construction of WASH facilities in schools and health facilities have been prepared and are being applied nationwide (see UNICEF, n.d.). These manuals are a multi-sectoral effort with inputs across education, health and WASH sectors and contain detailed design drawings as well as lists of required materials and equipment. These manuals are essential tools that will provide guidelines for supporting WASH infrastructure in Ethiopia’s schools and health facilities.

10.6 Water quality

Another important aspect of implementation is the regular monitoring and assessment of drinking water quality, both before and after new schemes have been installed. Responsibility for water quality is shared by the Ministry of Health (MoH) and the Ministry of Water, Irrigation and Energy (MoWIE), and their regional bureaus.

The MoWIE tests the water quality of proposed surface water and groundwater sources before undertaking the construction and commissioning of new schemes. In some parts of the country there are problems caused by the natural water chemistry such as high levels of fluoride, iron and salinity. The MoWIE is responsible for identifying these issues and implementing mitigation measures where appropriate.

The MoH is responsible for the periodic monitoring of water quality after water supply schemes are commissioned through its regional bureaus and woreda offices, testing the microbiological quality of the water to ensure the water is not contaminated and is safe to drink (Figure 10.9).

Summary of Study Session 10

In Study Session 10, you have learned that:

- The OWNP has established readiness criteria for all levels of administration that have to be fulfilled before funds are released for implementing WASH activities.

- The main approaches to implementing rural water supply schemes are woreda-managed projects (WMP), community-managed projects (CMP), NGO-managed projects, self-supply and multi-village schemes.

- Two important approaches to rural sanitation and hygiene promotion are community-led total sanitation and hygiene (CLTSH) and sanitation marketing.

- In pastoralist areas, the same approaches described for rural water supply can be used, but need to consider special conditions that apply in pastoral communities.

- The OWNP uses three categories of town based on water supply provision and management status. There are two financing arrangements used for urban WASH, grants and soft loans.

- Institutional WASH provision covers schools and health facilities. Implementation may be by WMP or CMP approaches.

- The quality of drinking water is another important aspect of WASH implementation. Monitoring and assessment of sources before development is by the MoWIE. The MoH is responsible for monitoring of water quality after installation is complete.

Self-Assessment Questions (SAQs) for Study Session 10

Now that you have completed this study session, you can assess how well you have achieved its Learning Outcomes by answering these questions.

SAQ 10.1 (tests Learning Outcome 10.1)

Fill in the gaps in the following sentences:

- A ……………… is a single combined plan for water supply, sanitation and hygiene schemes that integrates the separate plans from all WASH implementing organisations.

- ……………… are any activities that focus on knowledge, attitude and behavioural changes of the individual or the whole community.

- ……………… are the physical parts of a scheme such as well linings, pumps, latrine slabs, lavatory pans, construction materials etc.

- ……………… is the construction and use of small-scale water schemes at household level, such as hand-dug wells.

- ……………… is the identification of the sources and amounts of all possible funds for a project.

Answer

- A consolidated WASH plan is a single combined plan for water supply, sanitation and hygiene schemes that integrates the separate plans from all WASH implementing organisations.

- Software components are any activities that focus on knowledge, attitude and behavioural changes of the individual or the whole community.

- Hardware components are the physical parts of a scheme such as well linings, pumps, latrine slabs, lavatory pans, construction materials, etc.

- Self-supply is the construction and use of small-scale water schemes at household level, such as hand-dug wells.

- Resource mapping is the identification of the sources and amounts of all possible funds for a project.

SAQ 10.2 (tests Learning Outcomes 10.1 and 10.2)

- a.Give a general definition for readiness criteria.

- b.Why are the readiness criteria for the OWNP particularly important in terms of the flow of resources?

- c.What sort of readiness criteria are expected to be in place for OWNP at city/town level?

Answer

- a.Readiness criteria are conditions or things that need to exist or be done before starting an activity.

- b.The readiness criteria for the OWNP have particular significance because they are tied to the release of funds. There is a requirement that conditions set out in the readiness criteria have to be met before money is disbursed and physical implementation can take place.

- c.All cities and towns are expected to have prepared a consolidated annual WASH plan and had this approved. They have to establish the necessary organisational structure (e.g. Town Water Board) and have appropriate staff in place. They need to organise their financial systems so there are separate budget lines for water supply and sanitation. They need to ensure M&E staff and procedures are established and that National WASH Inventory data has been made available.

SAQ 10.3 (tests Learning Outcome 10.3)

Listed in the table below are various approaches to implementing the OWNP. In the second column, write down if the approach is relevant to water, sanitation or hygiene, or more than one of these three. In the third column, identify whether the approach is used in rural, urban, pastoralist or institutional WASH.

| Approach | Water? Sanitation? Hygiene? | Rural? Urban? Pastoralist? Institutional? |

|---|---|---|

| Community-managed project | ||

| Sanitation marketing | ||

| Multi-village scheme | ||

| Grant financing | ||

| CLTSH | ||

| NGO-managed project |

Answer

| Approach | Water? Sanitation? Hygiene? | Rural? Urban? Pastoralist? Institutional? |

|---|---|---|

| Community-managed project | water | rural, pastoralist and institutional |

| Sanitation marketing | sanitation | rural (mostly) but also the others |

| Multi-village scheme | water | rural |

| Grant financing | water, and also sanitation and hygiene | urban |

| CLTSH | sanitation and hygiene | rural (mostly) but also the others |

| NGO-managed project | water | rural, pastoralist and institutional |

SAQ 10.4 (tests Learning Outcome 10.4)

What are the differences between the community-managed project (CMP) approach and the woreda-managed project (WMP) approach?

Answer

In the CMP approach, communities are supported to undertake all stages of a project from initiation through planning to implementation and management continuing into the future. These projects use funds that are transferred to, and managed by, the community.

In the WMP approach, the Woreda WASH Team takes the lead. They are responsible for administering funds allocated to woreda, kebele or community for capital expenditure on water supply and sanitation activities. Although the kebele administration and WASHCOs are involved in project planning, implementation, monitoring and commissioning the project, the WWT is the Project Manager and is responsible for contracting, procurement, inspection, quality control and handover to the community.